Abstract

Context:

Alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement.

Aims:

To search for evidence for the use of periprosthetic autologous fat transplantation.

Setting and Design:

Systematic review.

Materials and Methods:

We searched in PubMed Central, Elsevier ScienceDirect Complete, Wiley Online Library Journals, Ovid Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, and Cochrane Library plus Results. Six studies reported improved results with the use of autologous fat graft (AFG) in patients treated with a total joint replacement, mainly about increased mobility. Three studies involved patients from the same surgeon with increased inclusions and increased follow-up period. A 1997 study by Wolford showed a significant difference in heterotopic bone formation between patients treated with AFG, compared to those who were not, indicating the potential and usefulness of AFG.

Conclusion:

A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial of this promising concept is warranted before justifying common application because of the added morbidity and the questionable advantage.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, fat, replacement, temporomandibular joint, transplants

INTRODUCTION

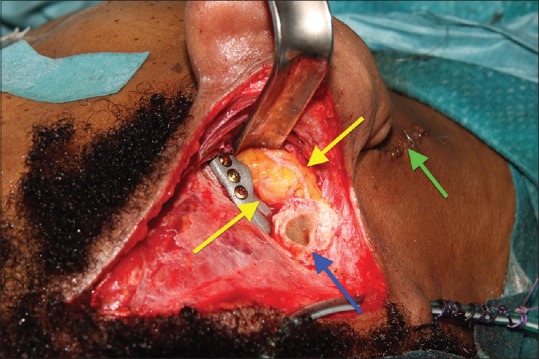

Calcifications and reankylosis are potential complications after alloplastic temporomandibular joint (TMJ) replacement. This process can occur through the formation of a hematoma after joint debridement, in which cells can differentiate to osteoblasts, which can deposit bone.[1] By wrapping the joint space with autologous fat grafts (AFGs), the dead space can be filled out, preventing the formation of a hematoma and as such has been advocated to counteract the occurrence of calcifications [Figure 1]. The aim of this narrative review was to find evidence for this rationale.

Figure 1.

Abdominal fat transplant surrounding the condylar head and neck (yellow arrows). A transparotid Biglioli approach (green arrow) was chosen for fixing the mandibular part and a retroauricular Mommaerts approach (blue arrow) for fixing the fossa part

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A computerized literature search was performed up to April 2018, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The following databases were used when conducting this search: PubMed Central, Elsevier ScienceDirect Complete, Wiley Online Library Journals, Ovid Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, and Cochrane Library Plus. The following search terms were used: (“TMJ” OR “TMJ”) AND (“replacement” OR “prosthesis”) AND (“fat”). No time or language limitations were imposed. The inclusion criteria used in this study were TMJ ankylosis, therapy involving surgery, and the use of AFG. The patient sample had to consist of human patients, with no boundary set for age or sex. The exclusion criteria were articles not involving the TMJ, not involving a prosthetically treated TMJ, and articles with a main focus on medical imaging.

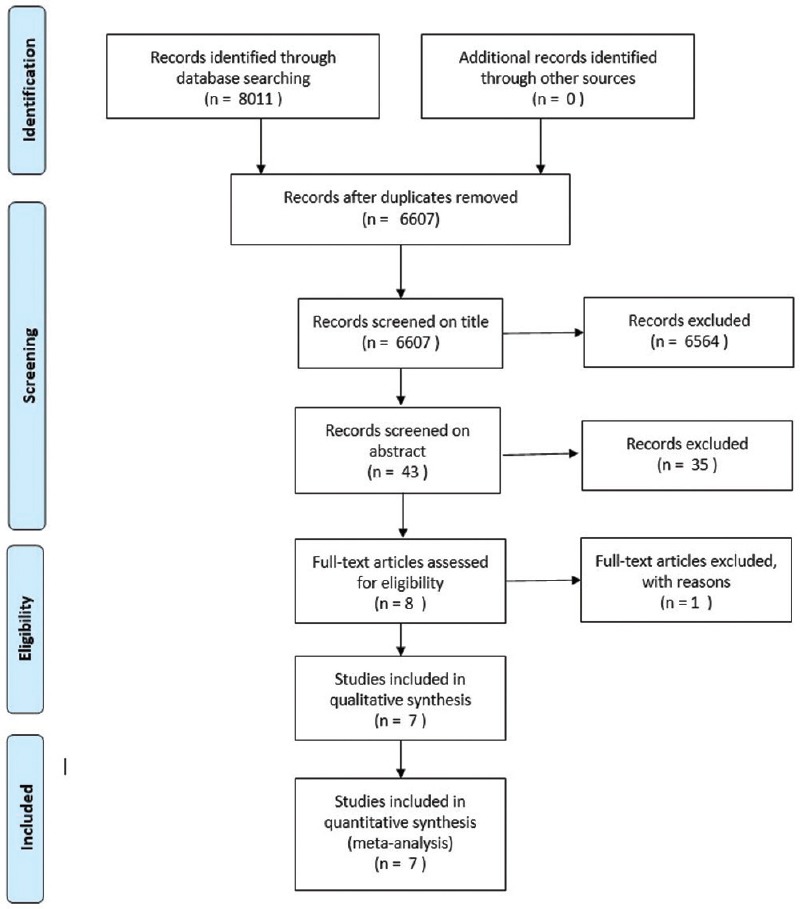

The initial search returned 8011 articles. After removal of duplicates, this number was reduced to 6607. Screening of both the title and abstract led to a further reduction to 43 and 8 articles, respectively. These articles were then fully read, and by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 7 articles were selected. No additional articles were included through handsearching the reference list of the included articles. A summary of this search can be found in the PRISMA flowchart [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Preferred repor ting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses chart

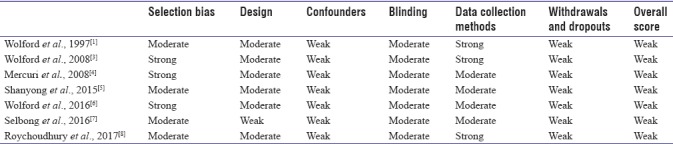

The quality assessment of the included studies was described with the effective public health practice project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool[2] [Table 1]. This tool evaluates eight different domains: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawal and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis. Each of these domains is given a rating of strong, moderate, or weak, yet only the first six domains make up for the global rating. If an article has no weak ratings and at least four strong ratings, it is considered strong. A moderate article has <4 strong ratings and no weak ratings, whereas an article is weak if it has at least two weak ratings. Normally, only strong and moderate articles are included in a review, yet as described in Table 1, all included articles have a weak quality based on the EPHPP instrument. Apart from the global rating, the overall intervention integrity of the studies included was considered strong regarding the number of patients receiving the intervention of interest, except a study by Wolford et al.,[1] with a weak assessment due to <60% of all patients included receiving the intervention. Measurement of consistency ranged from strong[3,5,6] to moderate assessment[7] or even weak.[1,4,8] In the studies conducted by Roychoudhury et al.,[8] Selbong et al.,[7] and Wolford et al.,[3,6] it is possible that the patients received an unintended intervention that might influence the results. All studies[1,3,4,5,6,7,8] performed a statistical analysis of their results, which was deemed sufficient, based on the evaluation criteria in the EPHPP instrument. Due to the paucity of data, we chose not to abandon this review based on this limitation and included these articles despite their weak rating. One case report was also included.

Table 1.

Quality assessment using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Tool

RESULTS

The pilot study published by Wolford et al.[1] in 1997 included 15 patients who received AFG, providing a total of 22 treated joints. The control group consisted of twenty patients. All patients had the same type of prosthesis made by TMJ Concepts (Ventura, CA, USA). The authors described an increase of maximal incisal opening (MIO) of 11.8 mm at the 12 months of follow-up consultation next to an increase of 6.3 mm in the control group. There was no difference in the decrease of pain level. While 35% of the control group had heterotopic bone formation which required reoperation, none of the patients in the fat-grafted group were diagnosed with heterotopic calcifications or fibrosis.

In 2008, Wolford et al.[3] published a second study with a larger patient sample to substantiate their results. One hundred fifteen patients were included in this study, and 5–20 cc of autologous fat from the abdominal wall was placed around the articulating portion of either the Christensen or TMJ Concepts total joint prosthesis. While the increase in MIO with 3.5 mm was somewhat disappointing for the Christensen system, the TMJ Concepts system showed an increase of 6.8 mm in MIO. Neither of the prostheses developed heterotopic bone formation that could be seen on radiographic images, nor did they report any donor site-specific complications such as the development of a seroma or infection.

The treatment efficacy of TMJ total joint replacement (TJR) with periarticular AFG in patients who had recurrent TMJ ankylosis was studied by Mercuri et al.[4] in 2008. They included a total of 20 patients, totaling 33 joint replacements, with a mean follow-up of 50.4 ± 28.8 months. While they found a significant reduction in pain, an improvement in quality of life (QoL), and an increase in MIO, no report on the recurrence of heterotopic bone formation was made.

Shanyong et al.[5] performed a retrospective single-center study involving 15 patients and 19 TMJ, to evaluate three modifications to the TMJ replacement technique. Among them was the use of an AFG harvested from the subcutaneous fat, to prevent fibrosis and heterotopic bone formation, by filling up the periprosthetic dead spaces. They concluded that in patients where AFG was used, there was no clinical nor radiographic sign of periprosthetic bone formation, while the two joints which were not treated with AFG showed the formation of heterotopic bone.

Wolford et al.[6] published another study in 2016 to address the treatment of TMJ ankylosis by placement of a TMJ TJR combined with AFG in 32 patients. This treatment proved to be successful, resulting in a significant increase in QoL, MIO, lateral extrusion, and jaw function, as well as decrease in pain. Furthermore, only 2 of 32 patients developed heterotopic bone formation. It is interesting to remark that both patients had been previously treated with a Vitek–Kent system.

In 2016, Selbong et al.[7] described three cases with heterotopic bone formation around a TMJ TJR. They removed the prosthesis, resected the heterotopic bone, and replaced the prosthesis, packing the articulating surface with AFG. No reoccurrence of heterotopic bone was reported.

In 2017, Roychoudhury et al.[8] published a prospective study evaluating the outcomes of TJR surgery along with the placement of AFG transplantation in 11 patients who suffered of TMJ ankylosis. They found a significant increase in MIO without adverse effects regarding the occlusion nor the QoL.

DISCUSSION

The technique of AFG transplantation in the TMJ was first documented by Blair[1,3] in 1913 as a treatment of ankylosis and in 1992 Thomas et al.[9] first described the use of AFG transplantation as a means of prevention of fibrosis and heterotopic calcification in hip prosthesis surgery. Heterotopic bone formation can be defined as the pathological formation of osseous tissue in nonskeletal tissues. While this process is not yet fully understood, it is currently presumed that trauma, such as surgery, resulting in the activation of the inflammatory system, as well as the innate immune system and the nervous system can lead to heterotopic bone formation. Through one of these systems, the production of several osteoinductive cytokines and growth factors such as skeletal growth factor can be promoted, leading to the differentiation and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteogenic cells. This can then lead to an overactivation of the bone morphogenetic proteins cascade, which, in a permissive environment, will result in heterotopic bone formation.[4,10]

While several preventive techniques such as the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bisphosphonates, and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy have been described, the preferential technique for prevention of fibrosis and calcification after prosthesis placement in orthopedic surgery is postoperative low-dose radiation.[4,10] However, due to the various side effects of radiation, the increased incidence of radiation-induced sarcomas as reported by several authors, and the important anatomical structures of head and neck, this option is best avoided.[4] The use of bisphosphonates is an unattractive option for obvious reasons as well and the use of NSAIDs can lead to gastrointestinal side effects, limiting the duration of application.[10]

A more invasive approach, which was first described by Thomas et al.[9] in 1992, is the use AFGs around a hip prosthesis, thereby filling out any negative space around the joint. There are only four research groups who published their findings regarding the use of AFG in TMJ TJR surgery, with Wolford et al.[1] being the first to step into the tracks of Thomas et al.[9] in 1997. All four reported positive results, yet it is not common practice to place AFG during TMJ TJR surgery. All three studies by Wolford et al.[1,3,6] were based on accumulating but overlapping data, gathered since 1992. There is room for external validation of these results with a study involving multiple centers, multiple surgeons, and a wider variety of patients.

Besides the obvious need for randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of AFG in TMJ TJR, it is of interest as to why this technique does not seem to have been widely implemented yet, despite its beneficial results. A possible explanation could be that the use of TMJ TJR remains relatively limited, resulting in the limited amount of literature dealing on the topic of heterotopic bone formation and AFG transplantation. However, another explanation might be that surgeons find results in daily practice not as good as they are depicted in the studies mentioned above.

CONCLUSION

Despite all the positive results regarding the use of AFG in TMJ TJR, scientific evidence remains limited. Further evaluation by means of a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed to achieve more definitive results of this seemingly promising technique.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolford LM, Karras SC. Autologous fat transplantation around temporomandibular joint total joint prostheses: Preliminary treatment outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolford LM, Morales-Ryan CA, Morales PG, Cassano DS. Autologous fat grafts placed around temporomandibular joint total joint prostheses to prevent heterotopic bone formation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2008;21:248–54. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2008.11928404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercuri LG, Ali FA, Woolson R. Outcomes of total alloplastic replacement with periarticular autogenous fat grafting for management of reankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanyong Z, Liu H, Yang C, Zhang X, Abdelrehem A, Zheng J, et al. Modified surgical techniques for total alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement: One institution's experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolford L, Movahed R, Teschke M, Fimmers R, Havard D, Schneiderman E, et al. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis can be successfully treated with TMJ concepts patient-fitted total joint prosthesis and autogenous fat grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:1215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selbong U, Rashidi R, Sidebottom A. Management of recurrent heterotopic ossification around total alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:1234–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roychoudhury A, Yadav R, Bhutia O, Aggrawal B, Soni B, Gowswami D, et al. Is total joint replacement along with fat grafts a new protocol for adult temporomandibular joint ankylosis treatment? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46:236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas BJ. Heterotopic bone formation after total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23:347–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercuri LG, Saltzman BM. Acquired heterotopic ossification of the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46:1562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]