Abstract

The aim of this study was to use a literature review to evaluate and compare the different biomaterials used in surgeries for the closure of the palatal and alveolar clefts as alternatives to isolated autografting. For the search strategy, the PubMed and Medline databases were used with the indexing terms “’cleft palate’ (Mesh), ‘biocompatible materials’ (Mesh), and ‘dentistry’ (Mesh).” There was no restriction on language or publication time. After the research, 26 articles were found, and then, only the filter for clinical trials was selected. With this methodology, five articles were selected. The full texts have been carefully evaluated. The main issue among the five selected articles was the closure of a cleft palate and/or alveolar bone with the use of different types of biomaterials (e.g. autogenous bone from the iliac crest and chin, deproteinized bovine bone (DBB), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), synthetic resorption based on calcium sulfate, and the engineering of bone tissue); they evaluated preoperative and postoperative clinically and through imaging tests. The autogenous bone associated with DBB or β-TCP significantly reduces the amount of autogenous bone harvested from the iliac crest, morbidity, and the hospitalization of the patient, and the isolated use of bovine hydroxyapatite resulted in lower bone density compared to that from autogenous bone.

Keywords: Alveolar bone grafting, biocompatible materials, bone transplantation, cleft palate

INTRODUCTION

In surgeries for the correction of dentofacial deformities in patients with cleft palates, secondary bone grafting in the residual alveolar cleft is crucial to solving these problems.[1,2,3] Reconstructions of cleft palates are done when the patient is close to 9 months old, and the secondary alveolar clefts are addressed when the patient is between 9 and 11 years old, before the eruption of the maxillary canine; this allows the teeth to erupt in the grafted area.[1,2,4,5]

The gold standard for these procedures involves the use of autogenous grafts arising from the iliac crest, but the capture surgery of this bone routinely comes with increased postoperative morbidity and lengthier hospital stays for patients.[6,7,8,9] Studies also show that some areas are excellent as donor sites – such as the mandibular symphysis,[10,11] rib,[12] skullcap,[13] and tibia.[14]

Bone substitutes – such as recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2, xenografts, or alloplastic materials – instead of autogenous bone have been widely used. These materials include β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), hydroxyapatite, deproteinized bovine bone (DBB), and synthetic polymers, among others.[14,15,16,17,18,19] Mixing autogenous grafts with other biomaterials is also a viable alternative that aims to decrease the donor area required for the procedure.[20]

Focusing mainly on the postoperative morbidity of these patients, scholars have searched for biomaterials presenting results close to or similar to autogenous bone in order to use less invasive techniques with satisfactory results.[21,22]

Therefore, this study aims to use a literature review to evaluate and compare the different biomaterials used in surgeries for the closure of the palatal and alveolar clefts as alternatives to isolated autografting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For the search strategy, the database PubMed/Medline was used with the indexing terms “’cleft palate’ (Mesh), ‘biocompatible materials’ (Mesh), and ‘dentistry’ (Mesh).” There was no restriction on language or publication time. After the research, 26 articles were found, and then, only the filter for clinical trials was selected.

The inclusion criteria were clinical trials related to the use of biomaterials to treat the palatal and alveolar clefts in cleft patients – regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity. Regarding the exclusion criteria, articles were removed if they were not related to the reconstruction of patients with palatine and alveolar clefts, to patients who had systemic changes that could affect the results, or to in vivo and in vitro studies.

RESULTS

With the methodology employed, 26 articles were found, and five references[21,23,24,25,26] were selected after their titles and summaries were read. The full texts have been carefully evaluated.

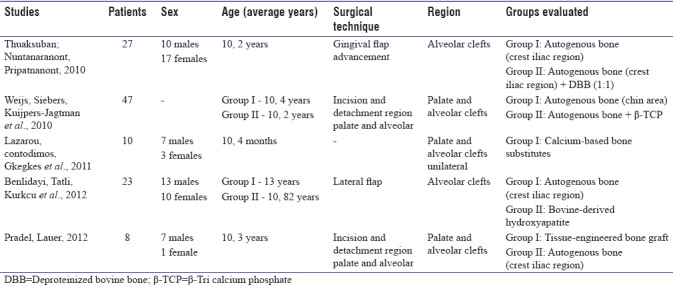

The main issue among the five selected articles was the closure of cleft palates and/or alveolar with the use of different types of biomaterials (autogenous bone from the iliac crest and chin, DBB, β-TCP, synthetic resorption based on calcium sulfate, and the engineering of bone tissue); the articles evaluated the preoperative and postoperative status clinically and through imaging tests. In the selected papers, one paper refers to the use of isolated autogenous bone,[21] three related papers addressed the combination of autogenous bone and substitute osseous material,[23,25,26] and one paper refers only to the use of osseous substitutes.[24] The participants in the studies totaled 115 patients, and they had an average age of 9.41 years. The characteristics evaluated in the five selected articles[21,22,23,24,25] can be viewed in Tables 1a and b.

Table 1a.

Features evaluated in the selected studies for the literature review

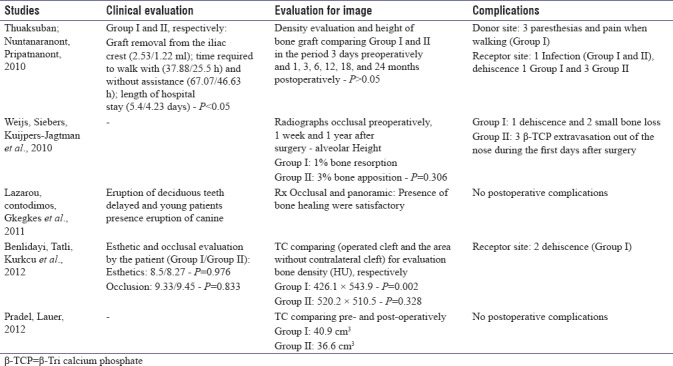

Table 1b.

Features evaluated in the selected studies for the literature review

The number of patients evaluated in the studies ranged from 8 to 47.[21,22,23,24,25] Regarding gender, 37 patients were male, 31 patients were female, and the other 47 patients were not cited. The average age of the patients was approximately 10.82 years, with a minimum age of 10.4 months and a maximum age of 13 years.

Regarding the techniques used for the closure of the cleft palate and/or alveolar, doctors in one study[21] conducted the gingival flap advancement to the alveolar cleft closure; doctors in two studies performed the incision and detachment of the palate and alveolus for the closure of the cleft palate and alveolar bone.[25,26] Doctors in one article[23] used the lateral flap technique to close an alveolar cleft, and another article[24] did not report the technique used to close the palate and alveolar cleft.

The doctors in most of the studies[21,23,25,26] used autogenous bone grafts in the reconstruction of defects instead of DBB,[21,23] calcium sulfate,[24] β-TCP,[25] or tissue engineering.[26] The main site adopted as a donor area was the iliac crest,[21,23,26] and doctors in only one article used bone from the chin.[25]

Among the aspects evaluated clinically, factors such as the time required to walk with or without assistance and the hospitalization time were significant when comparing the two groups (I and II).[21] It was noted that eruption delayed the deciduous teeth in older patients, and the eruption of the permanent canine was also evaluated.[24] The esthetic and occlusal changes in patients were also verified. Regardless of the group (I or II), no differences were observed between the aspects evaluated (P > 0.05).[23] Two articles[25,26] did not report any evaluation of clinical aspects.

During the analysis of imaging tests (occlusal radiographs, panoramic radiographs, and computed tomography scans), the densities of the postoperative bone in isolated uses of autogenous bone from the iliac crest or DBB were similar between Groups I and II (P > 0.05).[21] Similarly, the processing of the autogenous bone associated with β-TCP showed no differences between the bone formation and postoperative bone resorption (P = 0.306).[25] In comparisons of the site operated on with the contralateral site without the presence of a cleft, it was observed that the use of autogenous bone from the iliac crest increased the bone density evaluated by tomography (Hounsfield unit), and it was observed that the use of autogenous bone from the iliac crest increased the tomographic density (Hounsfield unit) (P = 0.002), whereas the isolated use of bovine hydroxyapatite resulted in a similar density to that of the bone not operated upon from the contralateral area without a cleft (P = 0.328).[23] The tomographic postoperative volumes used for closing the clefts (tissue engineering [Group I] or autogenous bone from the iliac crest alone [Group II]) were similar (40.9 cm3 for Group I and 36.6 cm3 for Group II).[26]

The most frequently reported complications were related to the donor areas (paresthesia and pain during walking)[21] and the receiving areas (infections[21] and suture dehiscence[21,23,25] for the groups that use autografting for bone reconstruction). Two papers have reported complications;[24,26] one utilized a substitute for a calcium sulfate base[24] and the other used graft tissue engineering or autogenous bone from the iliac crest.[26]

DISCUSSION

In relation to grafts in only the alveolar cleft region, the clinical trials in this review showed general alveolar bone maintenance independent of the material used – either in the isolated use of autogenous bone from the iliac crest, its association with DBB, or the use of isolated hydroxyapatite.[21,23]

In comparisons of the autogenous bone arising from the iliac crest region and its association with DBB (Group I and Group II, respectively) in a clinical evaluation,[21] it was noted that the results for the time it took patients to walk with help (37.88/25.5 h) and without (67.07/46.63 h), the length of stay (5.4/4.23 days), and the graft harvesting from the iliac crest (2.53/1, 22 ml) were all statistically significant (P < 0.05). The loss of the blood transoperative (150/122.5 ml) and the duration of surgery (2.68/2.29 h) were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). However, evaluations of the density and height of the grafts in Groups I and II in the period 3 days before the operation and 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the operation were similar (P > 0.05), showing that the association of biomaterials in Group II showed good results that were similar to those of autogenous bone but with lower postoperative morbidity for patients.

Compared with the same model of autogenous bone with bovine hydroxyapatite, the results of Benlidayi et al.[23] that were related to the esthetics and occlusion of patients were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In comparisons of bone density in the slots operated upon and the areas without slots (the contralateral area), the autologous bone had better results (426.1 × 543.9; P = 0.002) compared to those of isolated bovine hydroxyapatite (520.2 × 510.5; P = 0.328).

Thus, the autografts for medium and large defects, such as palatal and alveolar cracks, may lead to higher morbidity for the patient, greater volume loss, and longer times for recovery to normal functions, especially walking.[9] It was clear that, when unused autografts (iliac crest), most of the factors related to postoperative complications were reduced and still maintained the characteristics satisfying the bone-rebuilding process, such as the bone volume and the density of the postreconstruction of the bone tissue.[9,27,28] Therefore, the use of autografts is satisfactory, but they should be used in smaller quantities and should be supplemented with osteoconductive bone substitutes with slow degradation.

In evaluations of the graft in palatal and alveolar cleft region, the biomaterials used in the studies were autogenous bone; one study[26] used the iliac crest region as a donor area, another used the chin region,[25] and another used the autogenous bone associated with β-TCP.[25] Other studies used a resorbable bone substitute for a calcium sulfate base[24] or bone-tissue engineering, which consists of a preoperative bone biopsy (3–4 mm) that passes through the culture process and is seeded in a bovine collagen matrix resorbable (Osteovit® Braun, Melsungen, Germany); after a continuous layer of cells formed on the surface of the biomaterial, the grafts were performed.[26]

In 2010, Weijs et al.[25] conducted a study with 47 patients; they compared the use of autogenous bone (chin region) with the combination of autogenous bone and β-TCP. Through occlusal radiographs in preoperative, after 1 week and 1 year, in which the alveolar height was observed with 1% bone resorption (autogenous) and 3% bone apposition (autogenous and β-TCP); however, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.306), showing that it is not necessary to supplement the processing of grafts with β-TCP particles. The use of a resorbable bone substitute based on calcium sulfate, which also showed satisfactory bone healing, was assessed by occlusal and panoramic X-rays of the face.[24]

Despite the positive aspects observed in the association of biomaterials (autogenous and osteoconductive) at the closing of the bone clefts, the material must present the osteoconductive characteristic of slow degradation, as was observed for bovine hydroxyapatite.[21,23] The phosphate-based substitutes are propitious to osteoconductive action but have much more rapid degradation compared to that of other bone substitutes. The association of autogenous bone with β-TCP provides similar results. However, even with these results, the association may be interesting in bone reconstruction due to the lower amount of autogenous bone needed and the volume ratio available for osteoconductive biomaterials.

A viable alternative to replacing autogenous bone was demonstrated in 2012 by Pradel and Lauer[26] through tissue engineering – which involved a bone biopsy and culture of the collected cells with a collagen matrix, which made it possible to close cracks and alveolar palates with results similar to those of grafts of autogenous cancellous bone from the iliac crest. Thus, this cell culture showed that improvement in the postoperative condition of patients, because it is not necessary to use a donor area and it decreases morbidity after surgery. Therefore, further studies should analyze the application of stem cells as potential cells in bone formation, initially in animal models, to determine the best concentrations for the subsequent clinical applicability in the reconstruction of bone defects in the patients.[22,29,30]

CONCLUSIONS

Regarding the above clinical studies, it was concluded that the autogenous bone associated with DBB or β-TCP significantly reduces the amount of autogenous bone harvested from the iliac crest, the morbidity, and the hospitalization time of the patient and that the isolated use of bovine hydroxyapatite results in lower densities compared to those from autogenous bone. The use of bone tissue engineering is a promising alternative to the alveolar bone graft, but more in-depth studies should be carried out to enable its use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amanat N, Langdon JD. Secondary alveolar bone grafting in clefts of the lip and palate. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergland O, Semb G, Abyholm FE. Elimination of the residual alveolar cleft by secondary bone grafting and subsequent orthodontic treatment. Cleft Palate J. 1986;23:175–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyne PJ, Sands NR. Combined orthodontic-surgical management of residual palato-alveolar cleft defects. Am J Orthod. 1976;70:20–37. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(76)90258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abyholm FE, Bergland O, Semb G. Secondary bone grafting of alveolar clefts. A surgical/orthodontic treatment enabling a non-prosthodontic rehabilitation in cleft lip and palate patients. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;15:127–40. doi: 10.3109/02844318109103425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enemark H, Sindet-Pedersen S, Bundgaard M. Long-term results after secondary bone grafting of alveolar clefts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:913–9. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj AK, Wongworawat AA, Punjabi A. Management of alveolar clefts. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:840–6. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kortebein MJ, Nelson CL, Sadove AM. Retrospective analysis of 135 secondary alveolar cleft grafts using iliac or calvarial bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:493–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90172-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadove AM, Nelson CL, Eppley BL, Nguyen B. An evaluation of calvarial and iliac donor sites in alveolar cleft grafting. Cleft Palate J. 1990;27:225–8. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569(1990)027<0225:aeocai>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raposo-Amaral CA, Denadai R, Chammas DZ, Marques FF, Pinho AS, Roberto WM, et al. Cleft patient-reported postoperative donor site pain following alveolar autologous iliac crest bone grafting: Comparing two minimally invasive harvesting techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:2099–103. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borstlap WA, Heidbuchel KL, Freihofer HP, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Early secondary bone grafting of alveolar cleft defects. A comparison between chin and rib grafts. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990;18:201–5. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freihofer HP, Borstlap WA, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Voorsmit RA, van Damme PA, Heidbüchel KL, et al. Timing and transplant materials for closure of alveolar clefts. A clinical comparison of 296 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21:143–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eppley BL. Donor site morbidity of rib graft harvesting in primary alveolar cleft bone grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:335–8. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200503000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen M, Figueroa AA, Haviv Y, Schafer ME, Aduss H. Iliac versus cranial bone for secondary grafting of residual alveolar clefts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:423–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes-Ferreira PH, Okamoto R, Ferreira S, De Oliveira D, Momesso GA, Faverani LP, et al. Scientific evidence on the use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;20:223–32. doi: 10.1007/s10006-016-0563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallman M, Cederlund A, Lindskog S, Lundgren S, Sennerby L. A clinical histologic study of bovine hydroxyapatite in combination with autogenous bone and fibrin glue for maxillary sinus floor augmentation. Results after 6 to 8 months of healing. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2001;12:135–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2001.012002135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallman M, Lundgren S, Sennerby L. Histologic analysis of clinical biopsies taken 6 months and 3 years after maxillary sinus floor augmentation with 80% bovine hydroxyapatite and 20% autogenous bone mixed with fibrin glue. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2001;3:87–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2001.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasabah S, Simůnek A, Krug J, Lecaro MC. Maxillary sinus augmentation with deproteinized bovine bone (Bio-oss) and impladent dental implant system. Part II. Evaluation of deprotienized bovine bone (Bio-oss) and implant surface. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2002;45:167–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maiorana C, Redemagni M, Rabagliati M, Salina S. Treatment of maxillary ridge resorption by sinus augmentation with iliac cancellous bone, anorganic bovine bone, and endosseous implants: A clinical and histologic report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2000;15:873–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tadjoedin ES, de Lange GL, Bronckers AL, Lyaruu DM, Burger EH. Deproteinized cancellous bovine bone (Bio-oss) as bone substitute for sinus floor elevation. A retrospective, histomorphometrical study of five cases. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:261–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pripatnanont P, Nuntanaranont T, Vongvatcharanon S. Proportion of deproteinized bovine bone and autogenous bone affects bone formation in the treatment of calvarial defects in rabbits. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thuaksuban N, Nuntanaranont T, Pripatnanont P. A comparison of autogenous bone graft combined with deproteinized bovine bone and autogenous bone graft alone for treatment of alveolar cleft. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:1175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bajestan MN, Rajan A, Edwards SP, Aronovich S, Cevidanes LH, Polymeri A, et al. Stem cell therapy for reconstruction of alveolar cleft and trauma defects in adults: A randomized controlled, clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017;19:793–801. doi: 10.1111/cid.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benlidayi ME, Tatli U, Kurkcu M, Uzel A, Oztunc H. Comparison of bovine-derived hydroxyapatite and autogenous bone for secondary alveolar bone grafting in patients with alveolar clefts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:e95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarou SA, Contodimos GB, Gkegkes ID. Correction of alveolar cleft with calcium-based bone substitutes. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:854–7. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31820f7f19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weijs WL, Siebers TJ, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Bergé SJ, Meijer GJ, Borstlap WA, et al. Early secondary closure of alveolar clefts with mandibular symphyseal bone grafts and beta-tri calcium phosphate (beta-TCP) Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pradel W, Lauer G. Tissue-engineered bone grafts for osteoplasty in patients with cleft alveolus. Ann Anat. 2012;194:545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdulrazaq SS, Issa SA, Abdulrazzak NJ. Evaluation of the trephine method in harvesting bone graft from the anterior iliac crest for oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:e744–6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez GD, Hijji FY, Narain AS, Yom KH, Singh K. Iliac crest bone graft: A minimally invasive harvesting technique. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30:439–41. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herford AS, Miller M, Signorino F. Maxillofacial defects and the use of growth factors. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2017;29:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gładysz D, Hozyasz KK. Stem cell regenerative therapy in alveolar cleft reconstruction. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:1517–32. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]