Abstract

Sedation in dentistry has been a controversial topic due to questions being raised over its safety, especially in dental chair. Dental fear and anxiety are not only common in children but also significantly prevalent among adults due to high intensity of pain. Sharing of airway between the anesthesiologist and the dentist remains the greatest challenge. The purpose of this review is to study the recent trends in conscious sedation in the field of dentistry from an anesthesiologist's perspective. It will provide a practical outline of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and routes of administration of the drugs or gases used.

Keywords: Benzodiazepines, ketamine, propofol, sedation, sevoflurane

INTRODUCTION

Conscious sedation is a technique in which the use of a drug or drugs produces a state of depression of the central nervous system (CNS) enabling treatment to be carried out, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained throughout the period of sedation. The drugs and techniques used to provide conscious sedation for dental treatment should carry a margin of safety wide enough to render loss of consciousness unlikely.[1] Conscious sedation retains the patient's ability to maintain a patent airway independently and continuously.

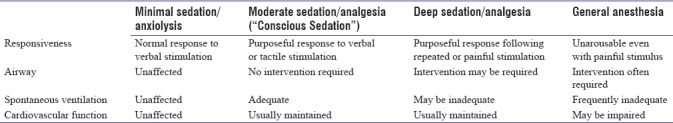

Continuum of depth of sedation as approved and amended by the American Society of Anesthesiologists, House of Delegates on October 15, 2014, is shown in Table 1.[2]

Table 1.

Continuum of depth of sedation

Conscious sedation is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which the patient responds purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. No interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.[3]

Careful presedation evaluation with respect to airway, fasting, and understanding about the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drugs must be established. Availability of airway management equipment, venous access, and appropriate intraoperative monitoring and well-trained staff in the recovery area must be ensured.[4]

Conscious sedation can be administered through various routes such as oral, intramuscular, intravenous, and inhalational.

CHALLENGES IN DENTAL CONSCIOUS SEDATION

The challenges in dental conscious sedation are as under:[4,5]

Shared airway between the dentist and the anesthesiologist

Phobia and anxiety

Coexisting medical conditions such as cardiac anomalies, mental instability, and epilepsy

Chances of arrhythmias during surgery due to trigeminal nerve stimulation

Enlarged tonsils and adenoids in children likely to precipitate respiratory obstruction

Risk of patient losing consciousness, respiratory, and cardiovascular depression

Vasovagal syncope due to the dependent position of legs in dental chair.

The anesthesiologist should be well prepared to face and tackle all the anticipated challenges as enumerated above. A detailed and thorough presedation checkup comprising assessment of airway, cardiorespiratory system, any congenital abnormality, medication history, and allergy must be done.

The operating area should be well equipped with all the resuscitation drugs/equipment required to resuscitate the patient in case of emergency.

INDICATIONS FOR CONSCIOUS SEDATION

Dental phobia and anxiety

Traumatic and long dental procedures

Medical conditions aggravated by stress such as angina, asthma and epilepsy

Children more than 1 year of age

Mentally challenged individuals

Ineffective local anesthesia due to any reason.

PREPARATION FOR CONSCIOUS SEDATION

Preparation for conscious sedation involves the preparation of patients as well as preparation in an operating area to meet any unforeseen challenges.[6]

Patient preparation

Consent for treatment: Valid informed consent is necessary for all patients receiving dental care under conscious sedation, and this should be confirmed in writing. In case of children, valid consent should be signed by the legal guardian

-

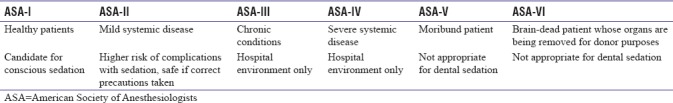

Presedation checkup: Patient's detailed history and examination are performed so as to classify according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification. Only patients who satisfy the criteria of ASA Grade I and II should be considered for sedation in dental surgery outside hospital. For pediatric patients, it is recommended that only the ASA Grade I patients are sedated outside a hospital environment[3] as in Table 2, prepared with recommendation from the article by Harbuz and O’Halloran[5]

Detailed airway examination is done for pediatric patients to look for adenotonsillar hypertrophy or any other anatomical airway abnormalities. In case of any underlying medical or surgical condition, the concerned specialist should be consulted for optimization before taking up the patient for dental procedure

-

Fasting instructions: Preoperative fasting for sedation is controversial and considered unnecessary by some authorities within dentistry for conscious sedation. Airway reflexes are assumed to be maintained during moderate and minimal sedation. It is not clear where the point of loss of reflexes lies. The chances of inadvertent oversedation and loss of protective airway reflexes at some point cannot be ruled out

For elective procedures using conscious sedation, the 2-4-6 fasting rule applies (that is 2 h for clear fluids, 4 h for breast milk, and 6 h for solids.). For emergency procedures where the fasting cannot be assured, the benefits of treatment and risk of the lightest effective sedation can be analyzed. Delaying the procedure may benefit the patient.

Table 2.

American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification with recommendation from the article by Harbuz and O'Halloran

Operating/procedure setup

The institution/clinic should have monitoring and resuscitation equipment and trained manpower available to handle any emergency situation.

Monitoring: Monitoring equipment such as ECG, pulse oximeter, ETCO2, NIBP, and defibrillator should be handy in working condition

Crash cart should be available with all the resuscitation equipment and drugs required to resuscitate a patient

Every procedure should be carried out after ensuring the availability of appropriate size suction catheter, adequate oxygen supply, functioning flowmeters and tubings for oxygen delivery to patient, and appropriate-sized airway equipment.

PHARMACOLOGY OF DRUGS USED FOR CONSCIOUS SEDATION

It is mandatory to secure an intravenous (IV) line with the help of an appropriate-sized IV cannula before administering any drug or inhalational anesthesia. In many cases, mild anxiolytic along with local anesthesia is sufficient to reduce fear and anxiety in the patient.

Nitrous oxide

Mixture of nitrous oxide (N2O) and oxygen is used as a sedative. N2O is a colorless gas used as an inhalational anesthetic agent. It is an anxiolytic/analgesic agent that causes CNS depression and varying degree of muscle relaxation and euphoria with hardly any effect on the respiratory system.[3] Recent research shows analgesic effects of N2O is initiated by the neuronal release of endogenous opioid peptides with activation of opioid receptors and descending gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and noradrenergic pathways that modulate nociceptive processing at the spinal level. Anxiolytic effect involves the activation of GABAA receptor through benzodiazepine-binding site. The anesthetic effect appears to be caused by inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors, thus removing its excitatory influence in the nervous system.[7] The technique employs subanesthetic concentrations of N2O delivered along with oxygen from dedicated machinery through a nasal mask. The N2O/oxygen delivery systems are manufactured with oxygen fail-safe devices that stop the flow of N2O when the flow of oxygen is stopped. The safety mechanism ensures delivery of at least 30% oxygen in all situations. N2O has low tissue solubility and high minimum alveolar concentration which enables rapid onset of action coupled with a rapid recovery; thus ensuring a controlled sedation and quick return to normal activities. It is very safe as the patient remains awake and responsive and reflexes are retained. The use of N2O is contraindicated in patients with common cold, porphyria, and COPD.

Sevoflurane

Sevoflurane is an ether inhalational anesthetic agent with low pungency, a nonirritant odor, and a low blood–gas partition coefficient. Its low solubility facilitates precise control over the depth of sedation and rapid and smooth induction and emergence from sedation.[8]

Sevoflurane, therefore, remains an ideal induction agent before starting infusion of a total IV anesthetic such as propofol to maintain sedation.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, including diazepam and midazolam, have proved to be safe and effective for IV conscious sedation. Their sedative and selective anxiolytic effects and wide margin of safety contribute to their popularity in dentistry. Apart from anxiolysis and amnesia, benzodiazepines are known to possess skeletal muscle relaxation and anticonvulsant activity; however, these drugs have no analgesic properties. Mechanism of action is through GABA-mediated opening of chloride channels. They have high lipid solubility giving rise to rapid onset of action.[9,10] They are normally added to N2O/oxygen for conscious sedation, as N2O produces the analgesic effects. The most commonly used benzodiazepine is midazolam. Its high first-pass metabolism makes it a short-acting one. It is used for conscious sedation in the pediatric dentistry. It is mixed with a sweet vehicle, such as simple syrup, and used orally either via drinking cup or through a syringe without needle and deposited in the retromolar area. Syrup can be given 20 min before the procedure. Dose under 25 kg is 0.3–0.5 mg/kg in adults but should be administered in a hospital setup only. It can also be given intramuscularly, intravenously, rectally, and nasally. Its effects are enhanced by various drugs such as opioids, clonidine, antidepressants, antipsychotics, erythromycin, antihistaminics, alcohol, and antiepileptics and should be avoided or used with caution.

All practitioners using these drugs must have flumazenil, the specific benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, as one of the emergency drugs in the institution. Flumazenil causes rapid reversal of all benzodiazepines. However, it is contraindicated in patients taking benzodiazepines for seizure disorder or high doses of tricyclic antidepressants.

Ketamine

Ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative, is an NMDA receptor antagonist. It is a unique drug giving complete anesthesia and analgesia with preservation of vital brain stem functions. This “dissociative” state has been described as “a functional and neurophysiological dissociation between the neocortical and limbic systems.” Dissociation results in a state of lack of response to pain with preservation of cardiovascular and respiratory functions despite profound amnesia and analgesia, described as “Catalepsy.” This trance-like state of sensory isolation provides a unique combination of amnesia, sedation, and analgesia.[11] The eyes often remain open, though nystagmus is commonly seen. Heart rate and blood pressure remain stable and are often stimulated possibly through sympathomimetic actions. Functional residual capacity and tidal volume are preserved with bronchial smooth muscle relaxation and maintenance of airway patency and respiration. The most commonly seen disadvantage of ketamine is emergence phenomenon which occurs in 5%–50% of adults in 0%–5% in children.[4] Ketamine increases salivary and tracheobronchial mucus gland secretions, so it is recommended to use an antisialagogue before administering ketamine.[12] The emetic side effect of ketamine producing an incidence of vomiting in 10% of children can be lessened by administering atropine which reduces salivary flow.[13] Laryngospasm reported in 0.4% of cases can be managed with positive pressure ventilation with 100% oxygen.

Ketamine can be given intramuscularly at a dose of 3–4 mg/kg or intravenously at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg as per the review conducted by Green et al.[14] However, administering a lower dose of the drug may be safer to achieve adequate levels of sedation in children due to the problem of potential severe respiratory depression.

Propofol

Propofol is chemically described as 2,6-diisopropylphenol. Being insoluble in water, it is available in white, oil-in-water emulsion which facilitates IV delivery of this fat-soluble agent. Propofol is readily oxidized to quinine which turns the suspension yellow in color after approximately 6 h of exposure to air. Propofol exerts its hypnotic actions by activation of the central inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. High lipophilicity ensures rapid onset of action at the brain, and rapid redistribution from central to the peripheral compartment causes quick offset of anesthetic action.[15] Elimination half-life is 2–24 h. The most significant hemodynamic effect is a decrease in arterial blood pressure and heart rate. Sedative doses actually have little or no effect on the respiratory system.[16] Apfel et al. studied six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea vomiting (PONV) and found that the use of propofol reduced risk for PONV by 19%.[17] Sedative doses are not analgesic, and a large proportion of patients experience pain on injection. To use an antecubital vein instead of a hand vein for the propofol, lidocaine admixture is a simple and effective way to avoid pain. Volatile anesthetic agents are used for the induction of anesthesia to avoid the struggle to get IV access before the child is asleep. With sevoflurane, propofol is given usually at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight, followed by maintenance dose ranging from 0.3 to 4 mg/kg/h.[18]

Opioids

All of the above-mentioned drugs do not have analgesic effects except ketamine. Opioid analgesic, therefore, needs to be supplemented. Fentanyl is a short-acting opioid 60–80 times more potent than morphine and with a rapid onset of analgesia and sedation.[3] Duration of action is 30–60 min. Fentanyl can be administered by parenteral, transdermal, nasal, and oral routes. A “lollipop” delivery system is more acceptable to children than any other route. Fentanyl being a lipophilic drug is absorbed from the buccal mucosa, metabolized in the liver, and secreted in the urine. Recommended dose is 1 μg/kg/dose IV which can be repeated by 1 μg/kg increments if required. Constipation, nausea, and vomiting are common side effects. Dose-dependent respiratory depression and occasionally bradycardia and chest wall rigidity are associated with rapid IV injection.[2,3]

Sufentanil

Sufentanil is a synthetic opioid analgesic drug, which is 5–10 times more potent than its parent drug fentanyl and 500 times as potent as morphine. It has shorter distribution and elimination half-lives. For outpatient surgery, IV sufentanil produces equivalent anesthesia to isoflurane or fentanyl. Recovery is rapid, and postoperative analgesia requirement is less.[19] However, side effects such as reduced chest wall compliance and high incidence of nausea and vomiting and prolonged discharge time as compared to midazolam make it an unpopular choice for premedication.[20]

SUMMARY

Conscious sedation is a technique meant for dealing with dental phobia and should not be considered an alternative to effective local anesthesia or good behavioral management. Route of administration and the drug should be selected on an individual patient basis. Importance of adequately trained staff in an area adequately equipped with monitoring tools along with importance of detailed presedation assessment cannot be overemphasized. When practicing sedation in a dental setting, awareness of limitations is necessary.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Craig DC. Royal College of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Surgeons of England. Conscious sedation for dentistry: An update. Br Dent J. 2007;203:629–31. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Quality Management and Departmental Administration. Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anaesthesia and levels of Sedation/Analgesia Last Amended; 15 October, 2014. [Last accessed on 1999 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management .

- 3.Galeotti A, Garret Bernardin A, D’Antò V, Ferrazzano GF, Gentile T, Viarani V, et al. Inhalation conscious sedation with nitrous oxide and oxygen as alternative to general anesthesia in precooperative, fearful, and disabled pediatric dental patients: A large survey on 688 working sessions. Biomed Res Int 2016. 2016:7289310. doi: 10.1155/2016/7289310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attri JP, Sharan R, Makkar V, Gupta KK, Khetarpal R, Kataria AP, et al. Conscious sedation: Emerging trends in pediatric dentistry. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11:277–81. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.171458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harbuz DK, O’Halloran M. Techniques to administer oral, inhalational, and IV sedation in dentistry. Australas Med J. 2016;9:25–32. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2015.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Standards of Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care. The Dental Faculties of the Royal College of Surgeons and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:9–18. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[9:AIUTAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goa KL, Noble S, Spencer CM. Sevoflurane in paediatric anaesthesia: A review. Paediatr Drugs. 1999;1:127–53. doi: 10.2165/00128072-199901020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finder RL, Moore PA. Benzodiazepines for intravenous conscious sedation: Agonists and antagonists. Compendium. 1993;14:972. 974, 976-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Averley PA, Girdler NM, Bond S, Steen N, Steele J. A randomised controlled trial of pediatric conscious sedation for dental treatment using intravenous midazolam combined with inhaled nitrous oxide or nitrous oxide/sevoflurane. Anesthesia. 2004;59:844–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howes MC. Ketamine for paediatric sedation/analgesia in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:275–80. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.005769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz P, Geelhoed GC, Wee C, Pascoe EM. Is atropine needed with ketamine sedation. A prospective, randomised, double blind study? Emerg Med J. 2006;23:206–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.028969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meredith JR, O’Keefe KP, Galwankar S. Pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1:88–96. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.43189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green SM, Hummel CB, Wittlake WA, Rothrock SG, Hopkins GA, Garrett W. What is the optimal dose of intramuscular ketamine for pediatric sedation? Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:21–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chidambaran V, Costandi A, D’Mello A. Propofol: A review of its role in pediatric anesthesia and sedation. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:543–63. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamaled SF. 4th ed. St. Louis (Mo): Mosby; 2003. Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management; pp. 26–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. Afactorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katoh T, Ikeda K. Minimum alveolar concentration of sevoflurane in children. Br J Anaesth. 1992;68:139–41. doi: 10.1093/bja/68.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monk JP, Beresford R, Ward A. Sufentanil. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1988;36:286–313. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198836030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binstock W, Rubin R, Bachman C, Kahana M, McDade W, Lynch JP, et al. The effect of premedication with OTFC, with or without ondansetron, on postoperative agitation, and nausea and vomiting in pediatric ambulatory patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:759–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]