Abstract

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) accounts for over half of prevalent heart failure (HF) worldwide, and prognosis after hospitalization for HFpEF remains poor. Due, at least in part, to the heterogeneous nature of HFpEF, drug development has proved immensely challenging. Currently, there are no universally accepted therapies that alter the clinical course of HFpEF. Despite these challenges, important mechanistic understandings of the disease have revealed that the pathophysiology of HFpEF is distinct from that of HF with reduced ejection fraction and have also highlighted potential new therapeutic targets for HFpEF. Of note, HFpEF is a systemic syndrome affecting multiple organ systems. Depending on the organ systems involved, certain novel therapies offer promise in reducing the morbidity of the HFpEF syndrome. In this review, we aim to discuss novel pharmacotherapies for HFpEF based on its unique pathophysiology and identify key research strategies to further elucidate mechanistic pathways to develop novel therapeutics in the future.

Keywords: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, pharmacotherapy, pathophysiology

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF), a global cardiovascular epidemic, is estimated to affect nearly 25 million patients worldwide (1). The hallmark of HF is the inability of the heart to adequately perfuse and thus oxygenate systemic tissue beds while maintaining normal cardiac filling pressures. In general, two distinct mechanisms result in this pathophysiology: systolic dysfunction (i.e., contractile impairment) and diastolic dysfunction [i.e., inadequate myocardial relaxation, resulting in stiffening of the left ventricle (LV)]. While systolic and diastolic dysfunction frequently coexist and result in elevated cardiac filling pressures at rest or with exertion, these distinct processes define the two clinical subcategories of HF: (a) HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), or systolic predominant HF, defined by an ejection fraction of ≤40%, and (b) HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), or diastolic predominant HF, defined by an ejection fraction of >50%.

HFpEF is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome that accounts for over half of prevalent HF and is accompanied by a dismal prognosis (2). After hospitalization for HF, the 1-year mortality rate among patients with HFpEF approaches 30% (3). Despite several studies conducted within the HFpEF clinical trial enterprise, there remains no widely accepted therapy that alters the natural progression of the disease or improves long-term clinical outcomes. While neurohormonal therapies, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, have clear salutatory effects for patients with HFrEF, such therapies have had at most a modest benefit in the HFpEF cohort (4–6). Since then, contemporary research endeavors have revealed insights into a distinct pathophysiology of HFpEF that is independent of dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. HFpEF is a systemic, multiorgan disease state, with multifaceted clinical manifestations depending on the predominant organ systems involved (7). Indeed, a machine learning analysis of HFpEF patients demonstrated that discrete phenotypes exist, each with varied prognoses (8). Such heterogeneity has created challenges for clinical diagnosis and treatment, along with difficulties in enrolling and studying patients in the clinical trial setting (9). Despite these challenges, through ongoing investigations, several potential therapeutic targets have emerged, and clinical trials for HFpEF are continually improving in terms of enrollment criteria and end points. In this review, we aim to discuss novel pharmacotherapies for HFpEF based on its unique pathophysiology and identify key strategies to further elucidate mechanistic pathways to develop phenotype-specific therapeutics moving forward.

A COMPLEX PATHOGENESIS

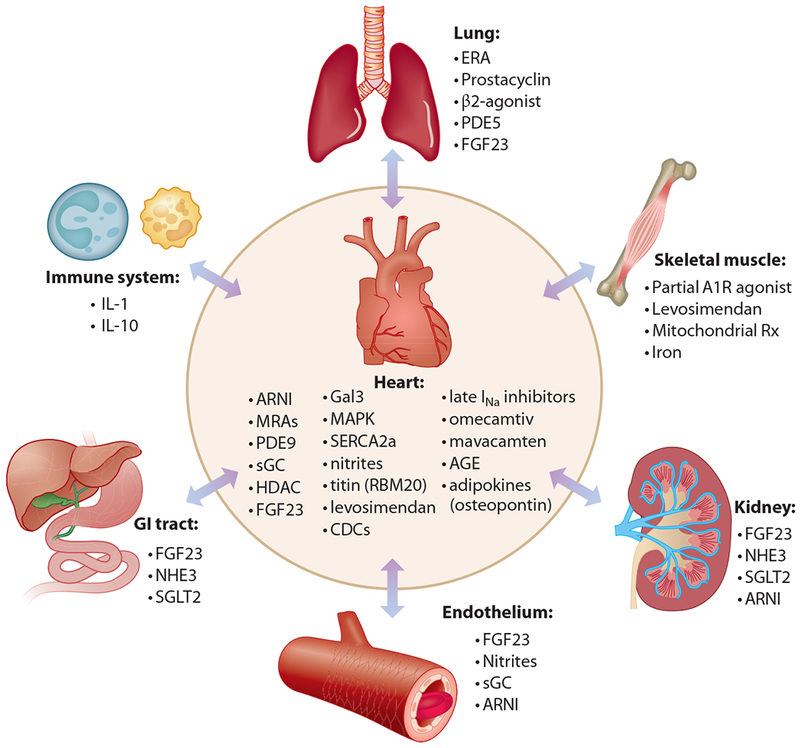

The recognition that HFpEF is a systemic syndrome that involves multiple organ systems and not simply due to left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and diastolic dysfunction has led to a paradigm shift in the conceptualization regarding HFpEF. The current leading theory is that HFpEF is rooted in pathologic immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation. Several comorbidities, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and atrial fibrillation can independently create an inflammatory cascade that ultimately leads to systemic microvascular endothelial dysfunction in various organ systems. Depending upon the organ systems predominantly affected, the clinical phenotypes of HFpEF are diverse and include LVH, fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction; pulmonary hypertension (PH); worsening CKD; and skeletal muscle weakness. Several drug targets have been identified along the inflammatory signaling cascade. In addition to systemic inflammation and resultant fibrosis, the following contribute to HFpEF pathogenesis and offer promise for future therapeutic targets: derangements in cardiac mechanics through sarcomere dysfunction; abnormal cardiac myocyte calcium handling; hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and visceral adiposity; maladaptive mitochondrial bioenergetics; and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction due to PH (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of current and future therapeutic targets for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Abbreviations: A1R, adenosine A1 receptor; AGE, advanced glycosylation end products; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibition; CDC, cardiosphere-derived cell therapy; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; Gal3, galectin 3; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IL, interleukin; INa, inward sodium current; MAPK, mitogen activated protein kinase; MRA, mineralocorticoid antagonist; NHE3, sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3; PDE, phosphodiesterase; RBM20, RNA binding motif 20; Rx, therapy; SERCA2a, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2A; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2.

Table 1.

Current pharmacotherapeutic clinical trials of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

| Trial name | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Intervention | Trial phase | Trial size | Follow-up | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic nitrite/nitrate | ||||||

| ONOH | NCT02918552 | Oral sodium nitrite | II | 18 | 8 weeks | Change in peak VO2 |

| KN03CK OUT HFPEF | NCT02840799 | Potassium nitrate | II | 76 | 6 weeks | Change in peak VO2 |

| Soluble guanylate cyclase pathway | ||||||

| CAPACITY-HFpEF | NCT03254485 | IW-1973 | II | 332 | 12 weeks | Change in peak VO2 |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor guanylate cyclase pathway | ||||||

| PARAGON-HF | NCT01920711 | Sacubitril-valsartan | III | 4,822 | Up to 57 months | Cardiovascular death and HF hospitalization |

| Antifibrotic therapies | ||||||

| SPIRRIT | NCT02901184 | Spironolactone | IV | 3,500 | 5 years | Time to death from any cause |

| REGRESS-HFpEF | NCT02941705 | Cardiosphere-derived cell therapy | II | 40 | Up to 3 years | Safety related events |

| PIROUETTE | NCT02932566 | Perfenidone | II | 200 | 12 months | Cardiac MRI ECV on Tl mapping |

| SGLT-2 inhibition | ||||||

| PRESERVED-HF | NCT03030235 | Dapagliflozin | IV | 320 | 6 weeks and 12 weeks | Change in NT-proBNP |

| EMPEROR-Preserved | NCT03057951 | Empagliflozin | III | 4,126 | Up to 38 months | Time to cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization |

| PH-HFpEF phenotype | ||||||

| ULTIMATE-HFPEF | NCT01599117 | Udenafil | III | 52 | 12 weeks | Change in peak VO2 |

| SERENADE | NCT03153111 | Maeitentan | II | 300 | 24 weeks | Change in NT-proBNP |

| SOUTHPAW | NCT03037580 | Treprostinil | III | 310 | 24 weeks | Change in 6MWT |

| BEAT-HFpEF | NCT02885636 | Inhaled albuterol | III | 30 | 10 min after exercise | Change in 20 watt exercise PVR |

| Levosimendan in HFpEF | NCT03541603 | Levosimendan | II | 36 | 6 weeks | Change in PCWP with bicycle exercise |

| Calcium handling | ||||||

| D-HART2 | NCT02173548 | Amakinra | II | 60 | 12 weeks | Change in peak VO2 |

| RAZE | NCT01505179 | Ranolazine | NA | 40 | 6 weeks | Change in exercise capacity |

| Istaroxime in HFpEF | NCT02772068 | Istaroxime | I | 30 | 90 min | Change in PCWP |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | ||||||

| PANACHE | NCT03098979 | Neladenoson | II | 305 | 20 weeks | Change in 6MWT |

| RESTORE-HF | NCT02814097 | Elamipretide | II | 46 | 4 weeks | Echocardiographic parameters of diastology at rest and exercise |

| FAIR-HFpEF | NCT03074591 | IV ferric carboxymaltose | II | 200 | 1 year | Change in 6MWT |

Abbreviations: 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; ECV, extracellular volume; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; VO2, oxygen consumption.

ENHANCING ENDOTHELIUM-CARDIOMYOCYTE PARACRINE SIGNALING

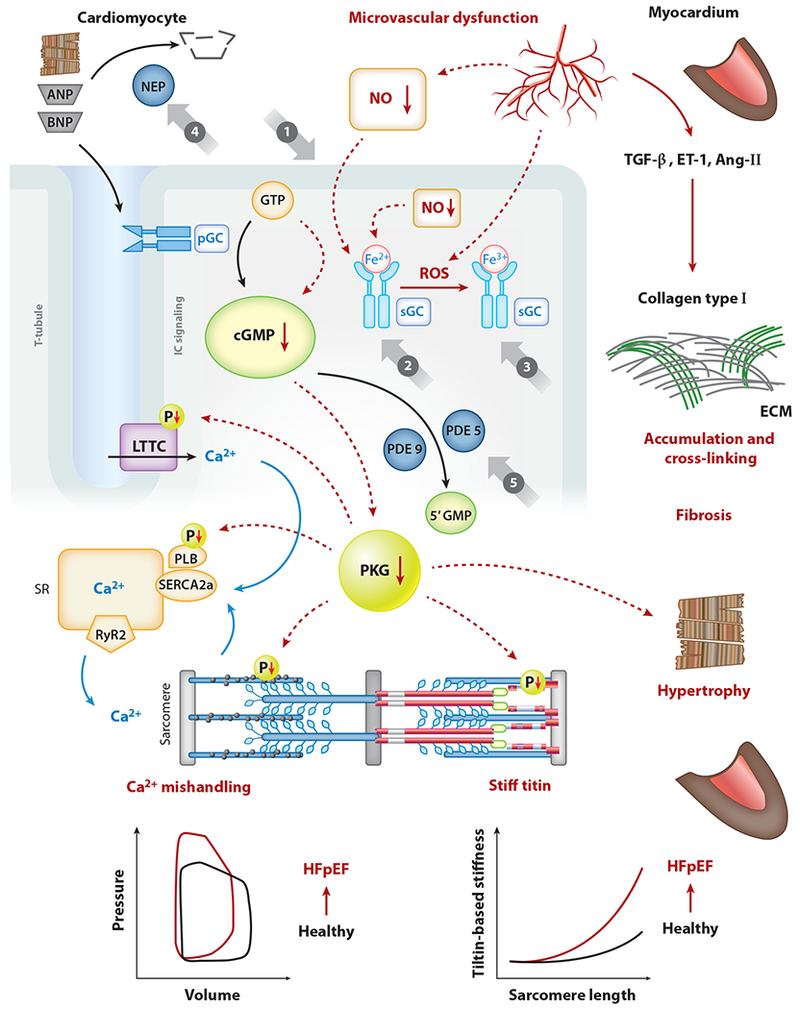

Endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of HFpEF and thought to result from inflammatory-driven reactive oxidative species (ROS) formation, which leads to local decrease in endothelial nitric oxide (NO) (10). The effects of endothelial NO deprivation are multifocal, ultimately leading to decreased activity of cardiomyocyte soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), decrease in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), and a reduction in protein kinase G (PKG) activity. Alteration in the myocyte sGC-cGMP-PKG pathway ultimately leads to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, increased stiffness of the cardiac myocyte due to isoform shifts in titin, and interstitial fibrosis (11, 12) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Classes of drugs that modulate the cGMP-PKG pathway in relation to SERCA2a within cardiac myocytes (cardiomyocytes). cGMP is produced by sGC, which is activated by NO, or by the transmembrane pGC, which is activated by natriuretic peptides (ANP, BNP). Class of NO and nitroxyl donors is shown (①). sGC stimulators (②) target only nonoxidized sGC (Fe2+); in contrast, sGC activators (③) target oxidized sGC (Fe3+) by ROS. NEPs responsible for ANP and BNP breakdown are indicated (④). PDE5 operates the breakdown of cGMP produced by sGC, while PDE9 is responsible for the breakdown of cGMP produced by pGC (⑤). Abbreviations: 5’GMP, guanosine 5’-monophosphate; Ang-II, angiotensin-Π; ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; ECM, extracellular matrix; ET-1, endothelin-1; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IC, intracellular; LTCC, L-type calcium channel; NEP, inhibitor of neprilysin; NO, nitric oxide; P, phosphate group; PDE5, phosphodiesterase 5; pGC, particulate guanylate cyclase; PKG, protein kinase G; PLB, phospholamban; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; SERCA2a, sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; SR, sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum; T-tubule, transverse tubule; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β. Figure adapted with permission from Kovacs et al. (12; https://creativecommons.Org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Restoring Nitric Oxide Balance

Given the hypothesized decreased NO bioavailability in HFpEF, it is conceivable that organic NO donors (nitrates) could restore NO balance in HFpEF and thus improve endothelial-myocyte paracrine signaling. Indeed, organic nitrates are often used in the treatment of patients with HFpEF. However, these drags increase ROS and may worsen endothelial dysfunction; furthermore, they may also be deleterious in HFpEF due to abnormal ventricular-arterial coupling, which predisposes these patients to labile blood pressures with acute changes in pre- and afterload. Thus, it may not be surprising that isosorbide mononitrate therapy resulted in decreased physical activity, lower blood pressure, and equivalent quality of life as compared to placebo when studied in the NEAT-HFpEF (Nitrate’s Effect on Activity Tolerance in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction) trial (13).

Inorganic nitrates, such as nitrite precursors, are biologically distinct from their organic counterparts, as they are reduced to NO preferentially during periods of hypoxia and acidosis and currently being studied in HFpEF. Intravenous infusion of sodium nitrite resulted in decreased exercise pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and increased cardiac output reserve (14). Several other inorganic nitrate preparations have also demonstrated benefit in short-term trials in HFpEF. Despite such promise, nebulized sodium nitrite had peak oxygen consumption levels similar to placebo in the recently completed INDIE-HFpEF (Inorganic Nitrite Delivery to Improve Exercise Capacity in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT02742129) cross-over trial (15).

Inadequate drug delivery from the nebulizer and patient noncompliance may have affected total drug delivery over the course of INDIE-HFpEF. The ongoing ONOH (Oral Nitrite in Older Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT02918552) trial is studying the effect of the oral formulation of this drag on exercise capacity (15). The effect of inorganic potassium nitrate on peak oxygen consumption is currently being studied in the phase II, placebo-controlled KNO3CK OUT HFPEF (Effect of KNO3 Compared to KC1 on Oxygen Uptake in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT02840799) trial. A recent comparison of the effects of organic versus inorganic nitrates on arterial hemodynamics provides insight into the differences between these two types of drags in HFpEF. Organic nitrates have minimal effects on systemic arterial impedance but result in significant cerebral vasodilation (hence the headaches in the NEAT-HFpEF trial), whereas inorganic nitrates (e.g., nitrites) have no effect on the cerebral vasculature but decrease systemic arterial impedance, which may be beneficial in HFpEF.

Prevention of Cyclic GMP Hydrolysis

To reap the pleiotropic benefits of PKG, maintenance of cGMP levels has been a target of therapy in HFpEF. Specific members of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) family of enzymes hydrolyze cGMP to its inert form. PDE5 and PDE9 are the primary regulators of cGMP, and inhibition of these enzymes raises myocyte cGMP levels. However, PDE5 inhibition with sildenafil showed no difference compared to placebo on exercise capacity among patients with HFpEF in a phase III clinical trial (16). A small trial of udenafil, a longer-acting PDE5 inhibitor, on exercise capacity among HFpEF patients is currently underway [A Randomized Trial of Udenafil Therapy in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (UFTIMATE-HFpEF; NCT01599117)]. Of note, concurrent PH and HFpEF (PH-HFpEF) was not a requirement for inclusion in the aforementioned trials of PDE5 inhibitors. PH-HFpEF represents a vulnerable subgroup that may derive significant benefit from PDE5 inhibition given the pulmonary vasodilatory effects of this drug. However, apart from a single-center study in HFpEF, there are no other data in the form of randomized controlled trials to support the use of sildenafil in PH-HFpEF (17).

Stimulation/Activation of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase

Enhanced activity of sGC results in increased cGMP levels and ultimately heightened levels of PKG activity. Although sGC stimulators act to stimulate the native, nonoxidized enzyme (Fe2+), sGC activators promote efficiency of oxidized sGC enzymes (Fe3+) that have been rendered less effective by direct ROS damage. Stimulators and activators of sGC have been studied in multiple arenas of cardiovascular disease, including HFpEF (18). Vericiguat, an sGC stimulator, was compared to placebo in the SOCRATES-PRESERVED (Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulator in Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction) trial. Although there was no difference in the coprimary end points of change in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels and left atrial size among the two groups, patients receiving vericiguat had improved quality of life scores, which were most evident in the physical limitation aspect of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (19). It is possible that sGC stimulators have varying tissue concentrations in the various organ systems involved in HFpEF; thus, vericiguat may have directly improved skeletal muscle function to a greater extent than cardiac function. It is also possible that the patients in SOCRATES-HFpEF, who were enrolled soon after hospitalization for HF, were simply too sick from a cardiac standpoint to demonstrate a benefit in the coprimary end points. A novel sGC stimulator (IW-1973) is currently being studied in the phase II CAPACITY-HFpEF (NCT03254485) randomized controlled trial, with cardiopulmonary exercise testing as the primary outcome measure, and thus will give insight into the effect of the drug on both cardiac and skeletal muscle function.

Neprilysin Inhibition: An Alternate Route to Restoration of Protein Kinase G

PKG is activated in a distinct, parallel mechanism to the aforementioned NO-sGC-cGMP pathway. Natriuretic peptides (NPs) bind to a receptor guanylate cyclase (rGC) of cardiac myocytes, thereby activating the enzyme to form cGMP and activate PKG (20). Thus, increased NP levels may augment PKG formation. Neprilysin is an enzyme that degrades NPs to inactive forms. Recently, neprilysin inhibition in combination with valsartan (sacubitril-valsartan) was shown to significantly improve clinical outcomes in patients with HFrEF as compared to enalapril in the landmark PARADIGM-HF (Prospective Comparison of Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) trial (21). Potential clinical benefit in HFpEF is supported by a phase II trial of sacubitril-valsartan, which revealed lower NP levels with ARB and neprilysin inhibition as compared to ARB alone (22). A pivotal phase III trial, PARAGON-HF (Efficacy and Safety of FCZ696 Compared to Valsartan on Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT01920711), has completed enrollment and will evaluate the drug’s effects upon clinical end points (23).

Unexplored Targets

While PDE5 inhibition has been and continues to be investigated in HFpEF, another PDE isoform, PDE9, also regulates the breakdown of cGMP, especially cGMP pools derived from the NP-rGC pathway. In contrast, PDE5 regulates cGMP pools from the NO-sGC pathway (20). Inhibition of PDE9 may be more applicable to the HFpEF population. PDE9, but not PDE5, is present in human myocardium and is upregulated in FVH (24). Inhibition of PDE9 resulted in decreased FVH in animal models of hypertension (24). Inhibition of PDE9 has yet to be studied in HFpEF. PDE9 inhibitors have recently been synthesized for the treatment of Alzheimer’s dementia and sickle cell anemia (25, 26).

In addition to alterations of the sGC-cGMP-PKG pathway, HF is characterized by decreased level and activity of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) via hydrolysis by PDE2, a consequence of which is heightened conversion of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and increased fibrosis (27). Pharmacologic inhibition of PDE2 and promotion of cAMP have not yet been studied in HFpEF and are potential future targets for therapy.

Cardiac endothelial dysfunction leads not only to myocardial stiffness through alteration of the sGC-cGMP-PKG pathway but to impaired microvascular function of the coronary vasculature. Microvascular dysfunction has recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of HFpEF: Impaired coronary flow reserve, a marker of coronary microvascular dysfunction, is an independent risk factor for diastolic dysfunction and hospitalization for HFpEF (28). It is likely that coronary microvascular ischemia results from the aforementioned systemic inflammation and contributes to HFpEF pathogenesis (28).

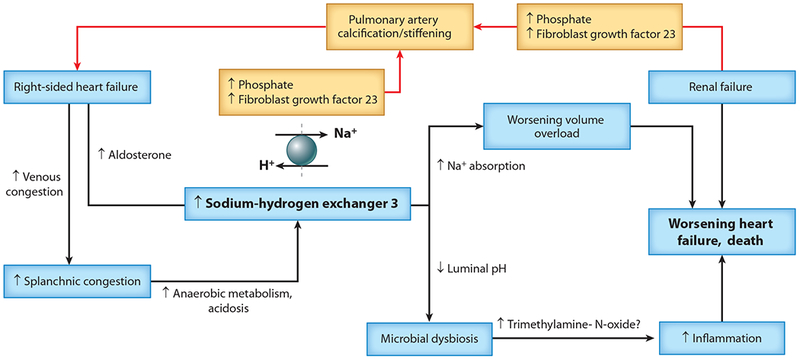

CKD is both a cause and consequence of HFpEF and the interplay between renal and myocardial dysfunction is a potential target for therapy, as endothelial dysfunction appears to mediate this interaction. In patients with CKD or microalbuminuria, levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a phosphaturic hormone, are elevated. FGF23 is a mediator of endothelial dysfunction through increased superoxide and decreased NO availability (29). Furthermore, FGF23 has been linked to FVH (30), and secondary hyperparathyroidism (which is associated with elevated FGF2 3 levels) may also be associated with the development of PH in the setting of CKD (31). For these reasons, FGF23 inhibition (32) may be a therapeutic target in HFpEF (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Right-sided heart failure, splanchnic hemodynamics, and the gut microenvironment in relation to the cardiorenal syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, and adverse outcomes. Right-sided heart failure is associated with the cardiorenal syndrome, worsening renal failure, worsening heart failure, and death. The mechanisms by which these processes are interrelated are not clear. Here, we propose a conceptual overview of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying those associations. Right-sided heart failure results in venous congestion and, in turn, splanchnic congestion. Venous congestion of the intestines results in reduced blood flow to the gut enterocytes, thereby resulting in hypoxia in these cells. Anaerobic metabolism ensues, with buildup of lactate and acidosis. In an effort to extrude H+ into the gut lumen, the sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) channel is upregulated resulting in increased Na+ absorption, which exacerbates fluid overload. Right-sided heart failure may also increase aldosterone secretion, which also stimulates NHE3. The increased H+ (decreased pH) in the gut lumen may result in microbial dysbiosis, increases trimethylamine-N-oxide. and may trigger inflammation that is involved in cardiac cachexia and poor outcomes in heart failure. Renal failure results in increased retention of phosphates and increased production of the phosphoturic hormone fibroblast growth factor 23. Both these foctors may play a role in the promotion of pulmonary artery stiffening, which is associated with increased pulmonary artery pressure and increased load on the right ventricle, thereby worsening right-sided heart failure. Figure adapted with permission from Polsinelli et al. (73).

ANTIFIBROTIC THERAPIES

Mineralocorticoid Antagonists and Loop Diuretics

Cardiac fibrosis is a multifaceted mechanistic process in patients with HFpEF. Aldosterone is a potent mineralocorticoid mediator of fibrosis through the generation of ROS by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (33). Spironolactone, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, has antifibrotic effects through aldosterone inhibition (34). The TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist) trial was a phase III, placebo-controlled trial of spironolactone therapy in HFpEF. After a median of 3.3 years, there was no difference between the two groups studied in the primary composite end point (cardiovascular death, aborted sudden death, HF hospitalization), although there were significantly fewer HF hospitalizations in the patients receiving spironolactone. However, significant issues occurred with enrollment and drug adherence in patients from Russia and Georgia, who constituted nearly half of the overall TOPCAT population, and affected the overall outcome of the trial (35, 36). In the Americas, spironolactone significantly reduced the primary composite end point as compared to placebo. Due to lingering uncertainty surrounding the TOPCAT trial, the SPIRRIT (Spironolactone Initiation Registry Randomized Interventional Trial in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT02901184) trial, a large-scale, phase IV, registry-based pragmatic trial of spironolactone, is currently underway.

Torsemide, a loop diuretic, appears to have antifibrotic effects based on multiple studies. Myocardial biopsies of HF patients on torsemide showed lower collagen levels as compared to HF patients on furosemide (37). The mechanism appears to be inhibition of the aldosterone receptor. While furosemide and torsemide both result in elevation of plasma renin and aldosterone levels, only torsemide appears to inhibit aldosterone binding to its receptor (38). It is thus reasonable to treat congestion in HFpEF with torsemide given its synergism with spironolactone and its greater bioavailability compared to furosemide (39).

Allogeneic Cardiosphere-Derived Cell Therapy

Regenerative stem cell therapies to reverse fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF are being actively investigated. Endomyocardial biopsy specimens cultured using specific techniques eventually form multicellular clusters, termed cardiospheres, which contain proliferative cells that express stem cell-related antigens (40). The cells within cardiospheres possess antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties, and thus serve as a promising therapy. In rodent models of HFpEF, cardiosphere-derived cell (CDC) intracoronary infusion improved diastolic function, reduced ventricular fibrosis, and decreased inflammatory markers (41). A phase II trial of allogeneic CDC intracoronary infusion among patients with HFpEF has commenced recruitment [Regression of Fibrosis and Reversal of Diastolic Dysfunction in HFpEF Patients Treated with CDCs (Regress-HFpEF; NCT02941705)].

Unexplored Targets

Although macrophages normally reside within myocardial tissue, macrophage concentration appears to rise in HFpEF, which may promote myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction (42). Both circulating and myocardial macrophage levels were increased in two mouse models of HFpEF, and myocardial biopsies of HFpEF patients have higher numbers of macrophages compared to age-matched healthy controls (43). Macrophages promote myocardial fibrosis through secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10), which leads to activation of cardiac myofibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition.

Based on extensive profiling of biomarkers of collagen synthesis, formation, and degradation, HFpEF is characterized by decreased collagen degradation and increased synthesis, leading to a net increase in collagen content and cardiac fibrosis (44). Several inflammatory cytokines have been implicated in the net increase in collagen content in HFpEF and serve as potential targets for therapy. IL-16, a cytokine that acts via the CD4 signaling pathway, is increased in patients with HFpEF compared to HFrEF (45). IL-16 is upregulated in rodent models of HFpEF and IL-16 levels correlated with diastolic dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis (45). Furthermore, tumor necrosis factor a is upregulated in HF and induces transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), leading to the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and collagen deposition (46, 47). TGF-β upregulation appears to be common to both HFpEF and HFrEF (48). In addition, posttranslational modification of collagen is dysregulated in HFpEF. Collagen is typically degraded by matrix metalloproteinases, which are inhibited by tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Inhibition of collagen degradation is enhanced in HFpEF as evidenced by increased levels of TIMPs (44). Improvement of collagen homeostasis in HFpEF may halt or reverse overall disease progression.

Galectin-3 is a paracrine mediator of fibrosis that is secreted from activated macrophages and promotes systemic inflammation and fibrosis. Inhibition of galectin-3 in rodent models of HF attenuates cardiac fibrosis and thus offers a potential target for pharmacotherapy (49). Currently, pharmacologic galectin-3 inhibitors have been synthesized and are under investigation in various conditions, including cancers and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Modified citrus pectin (MCP), a dietary supplement derived from plants, reduces galectin-3 in animal models of acute kidney injury (50). A clinical trial (NCT01960946) investigating the effect of MCP on serum markers of collagen among patients with hypertension is currently underway; the results of this study will likely be of relevance to HFpEF.

P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibition has been incompletely explored as a therapeutic target for HFpEF. P38 MAPK activity is upregulated in a variety of cardiac conditions, including atherosclerosis, ischemia, and HF (51). Enhanced activity results in abnormal intracellular calcium handing, LVH, and cardiac fibrosis (51). A MAPK inhibitor, losmapimod, showed neutral cardiovascular outcomes in the postmyocardial infarct population (52) but has not been studied in HFpEF.

TARGETING HYPERGLYCEMIA, INSULIN RESISTANCE, AND VISCERAL ADIPOSITY

Independent of obesity, diabetes remains a strong risk factor for HFpEF. Diabetes contributes to HFpEF through a variety of mechanisms, including the activation of protein kinase C leading to myocardial collagen deposition, enhanced ROS formation through deposition of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), and shifts in myocardial metabolism leading to lower phosphocreatine-to-adenosine triphosphate (PCr/ATP) ratios (53).

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibition

Recently, blockade of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) has shown promise for therapy in patients with HF and may even have utility independent of the presence of comorbid diabetes. SGLT-2 blockade within the proximal tubule of the nephron promotes natriuresis and glycosuria. In diabetic patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or at high risk, two SGLT-2 inhibitors, empagliflozin and canagliflozin, have demonstrated significant reductions in HF hospitalization, in addition to mortality (54, 55). The specific cardioprotective mechanisms of SGLT-2 inhibitors are not well defined and may include improved arterial stiffness and coronary blood flow through natriuresis and glycosuria, energy substrate shifts, and direct myocardial effects through decreased fibrosis (56). Two large-scale trials evaluating two SGLT-2 inhibitors, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, are currently recruiting HFpEF patients. The PRESERVED-HF (Dapagliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes or Pre-diabetes, and PRESERVED Ejection Fraction Heart Failure; NCT03030235) trial is a phase IV trial evaluating SGLT-2 inhibition in patients with diabetes or prediabetes, while in the EMPEROR-Preserved (Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT03057951) trial, hyperglycemia is not a prerequisite for trial enrollment. Smaller trials of distinct SGLT-2 inhibitors in HF, including canagliflozin and sotagliflozin, are also in process. During a time in which multiple classes of antidiabetic drugs have demonstrated cardiovascular adverse effects or neutrality in the HF population (57–59), SGLT-2 inhibitors appear to be a promising therapy. In fact, some consider SGLT-2 inhibitors to be smart diuretics (no neurohormonal activation, potential for improved renal function) that also have a glucose-lowering effect (60).

Unexplored Targets

AGEs are glycated and oxidized lipids or proteins and the formation of AGEs is increased in the setting of hyperglycemia. AGEs promote cardiovascular disease including HF, as they are potent stimulators of multiple signaling pathways in the vasculature and myocardium. Not only do AGEs form within the extracellular matrix of myocardium to promote stiffness, but AGEs also crosslink and stimulate the production of ROS and enhance p38 MAPK activity, leading to increased fibrosis and inflammation (61). Inhibitors of AGEs are a possible therapy for HFpEF given the strong association between hyperglycemia and HF. Indeed, alagebrium is a drug that disrupts AGE cross-linking, and a phase II trial (NCT01014572) of its effect upon diastolic function in elderly patients without HF is currently underway.

Obesity is a strong risk factor for HFpEF and appears to be a hallmark of a specific phenotype of HFpEF (8). Adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that secretes multiple adipokines that have widespread inflammatory effects. Specifically, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is associated with the development of HFpEF (62). In mouse models, VAT has been associated with increased levels of osteopontin, a phosphoprotein that regulates conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, thereby promoting fibrosis (63, 64). Indeed, mice with increased levels of VAT had increased cardiac fibrosis, and small molecule inhibition of osteopontin resulted in reversal of fibrosis (63). Adipokine modification, including osteopontin inhibition, requires further investigation in the treatment of HFpEF.

TREATMENT OF CONCURRENT PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

HFpEF predisposes patients to PH via two potential mechanisms: (a) progressive left atrial hypertension, leading to postcapillary PH, and (b) pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling, resulting in precapillary PH. A third potential mechanism is pulmonary venule remodeling, which has been relatively underexplored (65). Patients with PH-HFpEF suffer from poor clinical outcomes, likely due to progressive dysfunction of the RV with resultant right-sided HF (66–68). RV-pulmonary artery coupling is disturbed in patients with PH-HFpEF (68). Multiple therapies targeting PH in patients with HFpEF are in various stages of investigation. As mentioned above, PDE5 inhibitors and sGC stimulators have yielded neutral outcomes in patients with HFpEF; however, the degree and etiology of PH (i.e., pre- versus postcapillary) in these trial populations were not fully defined. The SERENADE (Study to Evaluate Whether Macitentan is an Effective and Safe Treatment for Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Pulmonary Vascular Disease; NCT03153111) trial is currently evaluating whether the endothelin antagonist macitentan improves NP levels in HFpEF patients with preexisting comorbid PH. Targeting of enriched, phenotypically distinct HFpEF cohorts, as in the SERENADE trial, will be important for future trial designs of HFpEF. Indeed, the phase III SOUTHPAW (Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Oral Treprostinil in Subjects with Pulmonary Hypertension and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT03037580) trial of the prostacyclin analog treprostinil will enroll HFpEF patients with documented PH on recent right-heart catheterization to better phenotype and enroll an enriched population. Agonism of the β2-adrenergic receptor by intravenous dobutamine administration to patients with HFpEF results in decreased pulmonary vascular resistance, which appears to be driven by improved RV-pulmonary artery coupling rather than enhanced RV contractility (68). The effect of β2 agonism through inhaled albuterol upon pulmonary vascular resistance will be studied in patients with HFpEF in the BEAT-HFpEF (Beta-adrenergic Agonists to Treat Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT02885636) trial.

RIGHT-SIDED HEART FAILURE: DIRECT MYOCARDIAL AND DOWNSTREAM SYSTEMIC TARGETS

Directly targeting RV dysfunction has been an area of recent interest in patients with HFpEF, as RV dysfunction is a predictor of poor prognosis (67). Levosimendan is a calcium-sensitizing drug with positive inotropic, vasodilatory, and lusitropic effects that is available outside the United States for the treatment of acute decompensated HF (69). In addition, levosimendan improves calcium sensitivity of skeletal muscle, including the diaphragm, in rat models of HF and patients with chronic lung disease, which could improve respiratory mechanics among patients with HFpEF (70, 71). As such, a phase II clinical trial of levosimendan in patients with HFpEF has recently been announced (NCT03541603). Milrinone, a PDE-3 inhibitor with inotropic and vasodilatory properties, has been utilized to treat patients with end-stage HFrEF. Recently, a small (n = 20) study randomized HFpEF patients to intravenous milrinone or placebo during right heart catheterization (72). Milrinone therapy improved right atrial pressure, PCWP, and cardiac output as compared to placebo.

Right-sided HF leads to venous congestion in multiple organ systems, including the gastrointestinal vascular bed and kidney (Figure 3). Visceral congestion appears to potentiate HF and volume overload and may lead to enterocyte hypoxia and intestinal acidosis. To maintain metabolic homeostasis, sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) is upregulated within enterocytes, which results in acid secretion into the gut lumen but increased intestinal absorption of sodium and subsequent volume overload (73). Tenapanor, an inhibitor of NHE3, offers promise in preventing further volume overload in patients with HFpEF and RV failure as it decreased extracellular fluid volume in a rat model of sodium overload (74). Intestinal acidosis induced by right-sided HF may also result in alteration in intestinal bacterial flora and systemic inflammation (73). Imbalance of the gut microbiome may lead to increased secretion of trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut-derived proinflammatory metabolite associated with cardiac fibrosis and poor prognosis in HF (75).

AMELIORATING DIASTOLIC DYSFUNCTION VIA IMPROVED CALCIUM HANDLING, MYOFIBRILLAR AUGMENTATION, AND MODIFICATION OF TITIN

Although HFpEF is now recognized as a systemic disorder, LV diastolic dysfunction still plays a central role in the pathogenesis of HFpEF in the majority of patients (76). Diastolic dysfunction can occur due to impaired LV relaxation and/or reduced LV compliance (i.e., increased LV diastolic stiffness). While LV diastolic stiffness is associated with worse outcomes in HFpEF, impaired relaxation is not (67). Nevertheless, improving LV relaxation may contribute to improved exercise tolerance and symptoms and therefore remains an important target in the treatment and potential prevention of HFpEF.

Interleukin-1 Inhibition

IL-1 is a proinflammatory cytokine that is upregulated in HFpEF and contributes to abnormal systemic and myocardial function. Specific to HFpEF, IL-1 appears to inhibit L-type calcium channels, downregulate phospholamban activity, and cause posttranscriptional changes in sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) (77). Dysregulation in calcium handling and excitation/contraction coupling ultimately leads to impaired lusitropy (cardiac relaxation) and diastolic dysfunction (Figure 2). In addition, excess cytosolic calcium leads to increased risk of afterdepolarizations and subsequent arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation, which carries a poor prognosis in patients with HFpEF (78). IL-1 blockade with anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, is currently being studied. The D-HART (Diastolic Heart Failure-Anakinra Response Trial) was a cross-over, placebo-controlled pilot study of anakinra in 12 patients with objective diastolic dysfunction. Anakinra therapy decreased the levels of inflammatory markers, which correlated with higher levels of oxygen consumption (79). A 30-patient, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (D-HART2; NCT02173548) evaluating the effect of anakinra upon peak oxygen consumption in HFpEF patients is ongoing (80). It remains unclear whether canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody specifically targeting the IL-1β isoform that has shown clinical benefit in patients with prior myocardial infarction (81), has a similar effect upon diastolic function. Importantly, therapies that reduce inflammation may have a variety of additional therapeutic effects in HFpEF, given the proposed central role of inflammation in the HFpEF syndrome (10).

Ranolazine, an inhibitor of the late inward sodium current (INa), may also regulate intracellular calcium and myocardial relaxation, making it a possible therapy for HFpEF. The late INa current is increased in HF, resulting in cytosolic calcium overload in cardiac myocytes, leading to decreased lusitropy. In the proof-of-concept RALI-DHF (Ranolazine for the Treatment of Diastolic Heart Failure) study, 20 patients were randomized to ranolazine infusion and oral therapy or placebo. Ranolazine decreased left ventricular end diastolic pressure and PCWP without changing NPs or exercise tolerance (82). The RAZE (Ranolazine on Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT01505179) trial will randomize 40 patients to oral ranolazine and evaluate change in exercise capacity.

Unexplored Targets

As previously described, SERCA2a is an integral regulator of intracellular calcium within cardiac myocytes. The inability to sequester calcium through SERCA2a leads to increased cytosolic calcium, which alters myocardial relaxation and contractility and contributes to arrhythmia risk. SERCA2a is inhibited by dephosphorylated phospholamban. A novel activator of SERCA2a, istaroxime, reduces SERCA2a–dephosphorylated phospholamban interaction, thus increasing calcium influx into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Istaroxime also inhibits Na/K-ATPase, resulting in improved inotropy. The HORIZON-HF (Hemodynamic Effects of Istaroxime in Patients with Worsening HF and Reduced LV Systolic Function) trial randomized HFrEF patients to istaroxime or placebo (83). Interestingly, patients in the istaroxime group not only had lower PCWP but also improved echocardiographic indices of diastolic function (84). A single-arm, phase I study (NCT02772068) is evaluating the effect of istaroxime on exercise PCWP in patients with HFpEF.

Cardiac myofibril relaxation may be enhanced by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, which warrant further investigation in HFpEF (85). HDACs catalyze acetyl group removal from various proteins. Histone deacetylation of cardiac myofibrils is associated with diastolic dysfunction in rodent models of HFpEF (86). Givinostat, an HDAC inhibitor under investigation for the treatment of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, prevented the development of diastolic dysfunction in rodent models of HFpEF (86). HDAC inhibitors appear to promote myocardial relaxation via direct effects on the cardiac myofibril, as HDAC inhibitors did not affect cardiac fibrosis, blood pressure, calcium handling, hypertrophy, or modifications of titin (86).

Titin is a large cardiac protein that acts as a myocardial spring and contributes to passive myocardial relaxation. Stiffness in titin has been associated with HFpEF through two mechanisms: (a) changes in titin isoform expression via splicing and (b) posttranslational modification, typically phosphorylation (87, 88). RNA binding motif-20 (RBM20) is a splicing factor of titin. Recently, it was discovered that mice that did not express RBM20 had an upregulation of certain ultracompliant isoforms of titin and improved diastolic function (89). Inhibition of RBM20 along with other potential modifications of titin may offer potential therapies for HFpEF patients with significant diastolic dysfunction.

DYNAMIC MODULATION OF THE CARDIAC SARCOMERE

The cardiac sarcomere, an amalgamation of several cardiac proteins, is dependent upon the release and subsequent uptake of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum for contraction and relaxation. While therapies that target calcium handing have been explored (see above), there is ongoing investigation to target the sarcomere and its constituent proteins in multiple cardiovascular disorders including HFpEF. The power of sarcomeres depends on the movement of the myosin head along the actin filament and the hydrolysis of ATP. Mavacamten, a small molecule inhibitor of ATP hydrolysis of the myosin heavy chain, was recently shown to reduce myocardial contractility (90). When administered chronically, mavacamten reduced ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis while increasing ventricular compliance (90). Reduction of LV mass is of primary interest in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM); a phase II, 21-patient trial (PIONEER-HCM; NCT02842242) of mavacamten’s effect on LV outflow tract obstruction in patients with HCM has completed enrollment. Among those in the high-dose (n = 11) and low-dose (n =10) groups, mavacamten significantly reduced LV outflow tract gradient and significantly increased peak oxygen consumption from baseline in the high-dose group (91). Further research is required to understand the safety and tolerability of mavacamten in patients with the more common (non-HCM) form of HFpEF. Omecamtiv, a small molecule activator of myosin (which stabilizes the lever arm of myosin in a primed position for its power stroke), is currently being studied for the treatment of HFrEF (92). HFpEF patients with significant RV failure may benefit from increased RV contractility through this mechanism. Overall, modification of the sarcomere is a novel and promising therapeutic target moving forward in select HFpEF patients.

MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION

The cardiomyocyte is one of the most metabolically active cells in the human body, as contraction and relaxation require significant levels of ATP. In both animal models and human studies of HF, mitochondria exhibit marked abnormalities, which result in decreased ATP production, increased production of ROS, and programmed cell death (apoptosis) (93). Furthermore, a metabolic shift from fatty acid oxidation to ketone body metabolism has been reported in HF, perhaps due to downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, a transcription factor responsible for transportation of fatty acids into mitochondria (93, 94). In addition, frequent opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) has been observed in HF, which ultimately leads to mitochondrial calcium release and contraction/relaxation decoupling. Indeed, patients with HFpEF have decreased ratios of PCr/ATP, a marker of bioenergetic dysregulation of the mitochondria (95). HFpEF is also associated with dysfunctional skeletal muscle oxygen utilization, which is partially due to decreased mitochondrial content and abnormal mitochondrial fusion (96). While multiple therapies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction, including ROS scavengers and coenzyme Q, have yielded neutral outcomes, several novel mitochondrial targets are currently under investigation.

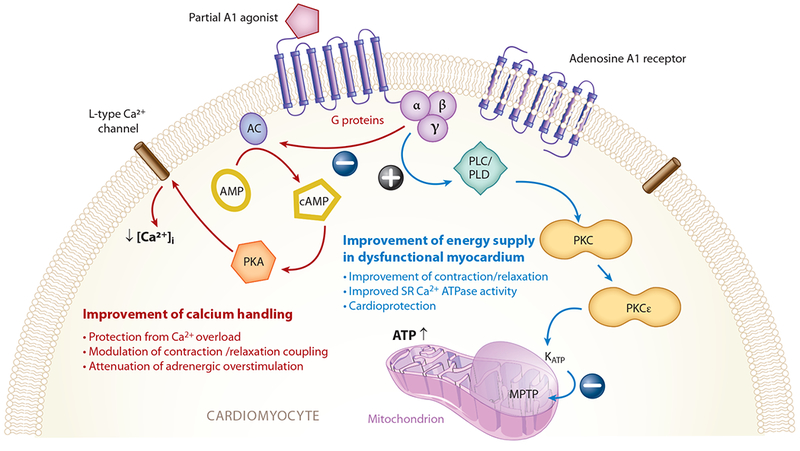

A partial agonist of the adenosine A1 receptor (AIR) has been developed and may be a promising therapy for HFpEF due to its hypothesized salutary effects upon the cardiac mitochondria (97) (Figure 4). Activation of the AIR results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity and subsequent increase in cAMP, which ultimately regulates cellular calcium cycling (98, 99). In addition, AIR agonism reduces the frequency of MPTP opening, thus regulating calcium handling by the mitochondria. Neladenoson, an AIR partial agonist, is under investigation in HFpEF patients in the PANACHE (A Trial to Study Neladenoson Over 20 Weeks in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT03098979) trial. Due to the partial agonism of the AIR, cardiac side effects of full agonism, including atrio-ventricular block, bradycardia, and hypotension, have not been observed.

Figure 4.

Adenosine A1 receptor signaling pathways in the felling heart. Abbreviations: AC, adenylyl cyclase; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; KATP, adenosine triphosphate–dependent potassium channel; MPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; PKA, phosphokinase A; PKC, phosphokinase C; PLC, phospholipase C; PLD, phospholipase D; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum. Figure adapted with permission from Greene et al. (97).

Elamipretide, a novel tetrapeptide, has shown potential beneficial effects on cardiac mitochondrial function. Elamipretide stabilizes cardiolipin, a phospholipid responsible for the organization of supercomplexes for oxidative phosphorylation (100, 101). The phase II RESTORE-HF trial (NCT02814097) is investigating the effect of elamipretide upon diastolic function in HFpEF patients compared to placebo and recently completed enrollment.

Iron supplementation in HFpEF is being explored due to its potential benefits upon mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are key sites for iron cellular processing and iron deficiency is associated with ultrastructural mitochondrial abnormalities in HF (102, 103). Iron deficiency can be problematic, but iron overload is also possible and may be deleterious to mitochondria (104, 105). Functional iron deficiency, defined as insufficient iron incorporation into erythroid precursors despite adequate total body iron stores, appears to affect a similar proportion of HFpEF and HFrEF patients (106). The FAIR-HFpEF (Effect of IV Iron on Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; NCT03074591) trial will evaluate the effect of iron supplementation on exercise capacity among a cohort of HFpEF patients.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR DRUG DEVELOPMENT AND CLINICAL TRIALS

Despite the large number of HFpEF trials currently in various stages of execution (Table 1), several important steps are needed to initiate and sustain a successful drug development regime in this clinical space. There are significant knowledge gaps regarding the diagnosis, pathophysiology, and clinical trial design in HFpEF. To formally address these issues, a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Working Group of clinical and research experts in HFpEF was assembled to identify gaps and outline future directions (95).

In our view, heterogeneity among patients is the major difficulty in undertaking clinical trials for HFpEF. As a research community, an important cognitive leap has been to view HFpEF as a systemic disease with multi-organ manifestations and phenotypes. The identification of specific subgroups by integrating multimodal clinical information (i.e., demographics, clinical comorbidities, laboratory markers, invasive hemodynamics, echocardiographic findings) allows for targeting therapeutics to potentially more homogeneous groups with the highest probability of clinical benefit.

Unsupervised machine learning of the HFpEF cohort is one such method to identify patients and categorize them into subgroups and various risk profiles (107). The vast majority of contemporary clinical trials of HFpEF have utilized an untargeted approach to enrollment. Deep phenotyping of the HFpEF cohort allows for enrichment trials, in which patient groups who have similar characteristics and perhaps a higher chance of benefiting from a therapy are selected (108). Given the complexity of HFpEF, novel clinical trial designs should be encouraged in future drug testing. For example, adaptive clinical trial design, which allows for continual changes in certain prespecified trial parameters, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, primary end point, and sample size, may yield more efficient, cost-effective clinical trials (108). An umbrella trial design, in which patients are enrolled based on a diagnosis of HFpEF and subsequently randomized to one of several targeted therapies based on their clinical phenotype, allows for fewer screening failures and higher enrollment rates while simultaneously testing multiple drug therapies (108). One approach is the use of the basket trial design, that is, the inclusion of patients based on an underlying therapeutic target that may be shared by multiple disease states. Such a concept is unprecedented in cardiology but may allow for efficient enrollment and permits the study of a specific pathophysiology that may be shared by multiple syndromes.

In addition to utilization of novel clinical trial design, a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of HFpEF is required to identify specific targets for therapy. Due to its inherent complexity, HFpEF has been difficult to study in animal models that yield findings akin to the clinical syndrome (109), creating challenges to studying the mechanism of the disease. Collaboration between clinical researchers and basic scientists across various disciplines and institutions will thus be integral to closing this knowledge gap. The increased use of phase T1 or 2A proof-of-concept trials may provide mechanistic insight into HFpEF and allow for the creation of small and large animal models for future investigation (110).

CONCLUSIONS

HFpEF, a clinical syndrome with many manifestations, has complex and incompletely characterized pathophysiologic mechanisms, and varying clinical prognosis. The clinical and economic burden of HFpEF is rising globally; no definitive therapy to date has altered its natural course. While previous clinical trials have not identified unequivocally effective therapies, the trials have revealed important gaps and provided insight regarding clinical trial design for HFpEF. Multiple potential therapeutic targets have been identified and are being investigated. Deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of HFpEF through increased collaboration across disciplines, the identification and study of specific HFpEF phenotypes via machine learning techniques, and the use of novel clinical trial designs offers promise for identifying and evaluating new therapeutic approaches for this major, unmet clinical need.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

S.S. has received research grants from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Corvia, and Novartis and consulting fees from Actelion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cardiora, Eisai, Ironwood, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, and United Therapeutics. He is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL107577, R01 HL127028, and R01 HL140731) and American Heart Association (16SFRN28780016 and 15CVGPSD27260148). R.P. is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute T32 postdoctoral training grant (T32HL069771).

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, et al. 2014. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 63:1123–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaduganathan M, Michel A, Hall K, Mulligan C, Nodari S, et al. 2016. Spectrum of epidemiological and clinical findings in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction stratified by study design: a systematic review. Eur. J. Heart Fail 18:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. 2006. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med 355:251–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, et al. 2008. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med 359:2456–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, et al. 2014. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med 370:1383–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, et al. 2003. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet 362:777–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW,Borlaug BA, vanHeerebeek L, Zile MR, et al. 2016. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a multiorgan roadmap. Circulation 134:73–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SJ, Katz DH, Selvaraj S, Burke MA, Yancy CW, et al. 2015. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 131:269–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel RB, Shah SJ, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Vaduganathan M. 2017. Designing future clinical trials in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: lessons from TOPCAT. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep 14:217–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulus WJ, Tschope C. 2013. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 62:263–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linke WA, Hamdani N. 2014. Gigantic business: titin properties and function through thick and thin. Circ. Res 114:1052–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kov´acs A, Alogna A, Post H, Hamdani N. 2016. Is enhancing cGMP-PKG signalling a promising therapeutic target for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction? Neth Heart J. 24:268–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redfield MM, Anstrom KJ, Levine JA, Koepp GA, Borlaug BA, et al. 2015. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med 373:2314–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borlaug BA, Koepp KE, Melenovsky V. 2015. Sodium nitrite improves exercise hemodynamics and ventricular performance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 66:1672–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy YNV, Lewis GD, Shah SJ, LeWinter M, Semigran M, et al. 2017. INDIE-HFpEF (Inorganic Nitrite Delivery to Improve Exercise Capacity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction): rationale and design. Circ. Heart Fail 10:e003862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, Semigran MJ, Lee KL, et al. 2013. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 309:1268–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. 2011. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation 124:164–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene SJ, Gheorghiade M, Borlaug BA, Pieske B, Vaduganathan M, et al. 2013. The cGMP signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2:e000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pieske B, Maggioni AP, Lam CSP, Pieske-Kraigher E, Filippatos G, et al. 2017. Vericiguat in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: results of the SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE patientS with PRESERVED EF (SOCRATES-PRESERVED) study. Eur. Heart J 38:1119–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omori K, Kotera J. 2007. Overview of PDEs and their regulation. Circ. Res 100:309–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, et al. 2014. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med 371:993–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A, Shah A, et al. 2012. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a phase 2 double-blind randomized controlled trial. Lancet 380:1387–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon SD, Rizkala AR, Gong J, Wang W, Anand IS, et al. 2017. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the PARAGON-HF Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 5:471–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DI, Zhu G, Sasaki T, Cho GS,Hamdani N, et al. 2015. Phosphodiesterase 9A controls nitric-xide-independent cGMP and hypertrophic heart disease. Nature 519:472–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su T, Zhang T, Xie S, Yan J,WuY, et al. 2016. Discovery of novel PDE9 inhibitors capable of inhibiting Aβaggregation as potential candidates for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep 6:21826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McArthur JG, Maciel T, Chen C, Fricot A, Kobayashi D, et al. 2016. A novel, highly potent and selective PDE9 inhibitor for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Blood 128:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vettel C, Lammle S, Ewens S, Cervirgen C, Emons J, et al. 2014. PDE2-mediated cAMP hydrolysis accelerates cardiac fibroblast to myofibroblast conversion and is antagonized by exogenous activation of cGMP signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 306:H1246–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Desai AS, Groarke JD, et al. 2018. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J 39:840–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ter Maaten JM, Damman K, Verhaar MC, Paulus WJ, Duncker DJ, et al. 2016. Connecting heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and renal dysfunction: the role of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Eur. J. Heart Fail 18:588–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B,Hu MC, Sloan A, et al. 2011. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest 121:4393–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akmal M, Barndt RR, Ansari AN, Mohler JG, Massry SG. 1995. ExcessPTHin CRF induces pulmonary calcification, pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy. Kidney Int. 47:158–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isakova T, Ix JH, Sprague SM, Raphael KL, Fried L, et al. 2015. Rationale and approaches to phosphate and fibroblast growth factor 23 reduction in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 26:2328–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown NJ. 2013. Contribution of aldosterone to cardiovascular and renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 9:459–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brilla CG, Matsubara LS, Weber KT. 1993. Antifibrotic effects of spironolactone in preventing myocardial fibrosis in systemic arterial hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol 71:A12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Denus S, O’Meara E, Desai AS, Claggett B, Lewis EF, et al. 2017. Spironolactone metabolites in TOPCAT—new insights into regional variation. N. Engl. J. Med 376:1690–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, et al. 2015. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 131:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Beaumont J, Querejeta R, Larman M, Diez J. 2007. Identification of a potential cardiac antifibrotic mechanism of torasemide in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 50:859–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida T, Yamanaga K, Nishikawa M, Ohtaki Y, Kido H, Watanabe M. 1991. Anti-aldosteronergic effect of torasemide. Eur. J. Pharmacol 205:145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellison DH, Felker GM. 2018. Diuretic treatment in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med 378:684–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK,Hare JM, et al. 2007. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation 115:896–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallet R, de Couto G, Simsolo E, Valle J, Sun B, et al. 2016. Cardiosphere-derived cells reverse heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in rats by decreasing fibrosis and inflammation. JACC Basic Transl. Sci 1:14–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim GB. 2018. Heart failure: Macrophages promote cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 15:196–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hulsmans M, Sager HB, Roh JD, Valero-Munoz M, Houstis NE, et al. 2018. Cardiac macrophages promote diastolic dysfunction. J. Exp. Med 215:423–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zile MR, Baicu CF. 2013. Biomarkers of diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis: application to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res 6:501–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamaki S, Mano T, Sakata Y, Ohtani T, Takeda Y, et al. 2013. Interleukin-16 promotes cardiac fibrosis and myocardial stiffening in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. PLOS ONE 8:e68893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL. 1996. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 27:1201–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan DE, Ferris M, Nguyen H, Abboud E, Brody AR. 2009. TNF-αinduces TGF-β1 expression in lung fibroblasts at the transcriptional level via AP-1 activation. J. Cell Mol. Med 13:1866–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westermann D, Lindner D, Kasner M, Zietsch C, Savvatis K, et al. 2011. Cardiac inflammation contributes to changes in the extracellular matrix in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail 4:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu L, Ruifrok WP, Meissner M, Bos EM, van Goor H, et al. 2013. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of galectin-3 prevents cardiac remodeling by interfering with myocardial fibrogenesis. Circ. Heart Fail 6:107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kolatsi-Joannou M, Price KL, Winyard PJ, Long DA. 2011. Modified citrus pectin reduces galectin-3 expression and disease severity in experimental acute kidney injury. PLOS ONE 6:e18683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arabacilar P, Marber M. 2015. The case for inhibiting p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in heart failure. Front. Pharmacol 6:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Donoghue ML, Glaser R, Cavender MA, Aylward PE, Bonaca MP, et al. 2016. Effect of losmapimod on cardiovascular outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315:1591–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulus WJ, Dal Canto E. 2018. Distinct myocardial targets for diabetes therapy in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 6:270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, et al. 2015. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med 373:2117–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, et al. 2017. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med 377:644–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lytvyn Y, Bjornstad P, Udell JA, Lovshin JA, Cherney DZI. 2017. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition in heart failure: potential mechanisms, clinical applications, and summary of clinical trials. Circulation 136:1643–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, et al. 2013. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med 369:1317–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Masoudi FA,Wang Y, Inzucchi SE, Setaro JF,Havranek EP, et al. 2003. Metformin and thiazolidinedione use in Medicare patients with heart failure. JAMA 290:81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Margulies KB, Hernandez AF, Redfield MM, Givertz MM, Oliveira GH, et al. 2016. Effects of liraglutide on clinical stability among patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316:500–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marx N, McGuire DK. 2016. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition for the reduction of cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur. Heart J 37:3192–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. 2006. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 114:597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valero-Munoz M, Li S, Wilson RM, Hulsmans M, Aprahamian T, et al. 2016. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induces beiging in adipose tissue. Circ. Heart Fail 9:e002724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sawaki D, Czibik G, Pini M, Ternacle J, Suffee N, et al. 2018. Visceral adipose tissue drives cardiac aging through modulation of fibroblast senescence by osteopontin production. Circulation. In press. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lenga Y, Koh A, Perera AS, McCulloch CA, Sodek J, Zohar R. 2008. Osteopontin expression is required for myofibroblast differentiation. Circ. Res 102:319–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fayyaz AU, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Konik EA, DuBrock HM, et al. 2017. Global pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure and preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 137:1796–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA. 2014. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J 35:3452–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burke MA, Katz DH, Beussink L, Selvaraj S, Gupta DK, et al. 2014. Prognostic importance of pathophysiologic markers in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail 7:288–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andersen MJ, Hwang SJ, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP, et al. 2015. Enhanced pulmonary vasodilator reserve and abnormal right ventricular: pulmonary artery coupling in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail 8:542–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosevear PR, Finley N. 2003. Molecular mechanism of levosimendan action: an update. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol 35:1011–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Hees HW, Andrade Acuna G, Linkels M, Dekhuijzen PN, Heunks LM. 2011. Levosimendan improves calcium sensitivity of diaphragm muscle fibres from a rat model of heart failure. Br. J. Pharmacol 162:566–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Hees HW, Dekhuijzen PN, Heunks LM. 2009. Levosimendan enhances force generation of diaphragm muscle from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med 179:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaye DM, Nanayakkara S, Vizi D, Byrne M, Mariani JA. 2016. Effects of milrinone on rest and exercise hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 67:2554–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polsinelli VB, Sinha A, Shah SJ. 2017. Visceral congestion in heart failure: right ventricular dysfunction, splanchnic hemodynamics, and the intestinal microenvironment. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep 14:519–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spencer AG, Labonte ED, Rosenbaum DP, Plato CF, Carreras CW, et al. 2014. Intestinal inhibition of the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 prevents cardiorenal damage in rats and inhibits Na+ uptake in humans. Sci. Transl. Med 6:227ra–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang WH, Wang Z, Fan Y, Levison B, Hazen JE, et al. 2014. Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide in patients with heart failure: refining the gut hypothesis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 64:1908–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Borlaug BA. 2014. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 11:507–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Tassell BW, Raleigh JM, Abbate A. 2015. Targeting interleukin-1 in heart failure and inflammatory heart disease. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep 12:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patel RB, Vaduganathan M, Shah SJ, Butler J. 2017. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights into mechanisms and therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther 176:32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Tassell BW, Arena R, Biondi-Zoccai G, Canada JM, Oddi C, et al. 2014. Effects of interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra on aerobic exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (from the D-HART pilot study). Am. J. Cardiol 113:321–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Tassell BW, Buckley LF, Carbone S, Trankle CR, Canada JM, et al. 2017. Interleukin-1 blockade in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the Diastolic Heart Failure Anakinra Response Trial 2 (D-HART2). Clin. Cardiol 40:626–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, et al. 2017. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N. Engl. J. Med 377:1119–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maier LS, Layug B, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Belardinelli L, Lee S, et al. 2013. RAnoLazIne for the treatment of diastolic heart failure in patients with preserved ejection fraction: the RALI-DHF proof-of-concept study. JACC Heart Fail. 1:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gheorghiade M, Blair JE, Filippatos GS, Macarie C, Ruzyllo W, et al. 2008. Hemodynamic, echocardiographic, and neurohormonal effects of istaroxime, a novel intravenous inotropic and lusitropic agent: a randomized controlled trial in patients hospitalized with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 51:2276–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shah SJ, Blair JE, Filippatos GS, Macarie C, Ruzyllo W, et al. 2009. Effects of istaroxime on diastolic stiffness in acute heart failure syndromes: results from the Hemodynamic, Echocardiographic, and Neurohormonal Effects of Istaroxime, a Novel Intravenous Inotropic and Lusitropic Agent: a Randomized Controlled Trial in Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure (HORIZON-HF) trial. Am. Heart J 157:1035–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lim GB. 2018. Heart failure: histone deacetylases and diastolic dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 15:196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeong MY, Lin YH, Wennersten SA, Demos-Davies KM, Cavasin MA, et al. 2018. Histone deacetylase activity governs diastolic dysfunction through a nongenomic mechanism. Sci. Transl. Med 10:eaao0144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borbely A, van der Velden J, Papp Z, Bronzwaer JG, Edes I, et al. 2005. Cardiomyocyte stiffness in diastolic heart failure. Circulation 111:774–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Borbely A, Falcao-Pires I, van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Edes I, et al. 2009. Hypophosphorylation of the stiff N2B titin isoform raises cardiomyocyte resting tension in failing human myocardium. Circ. Res 104:780–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Methawasin M, Strom JG, Slater RE, Fernandez V, Saripalli C, Granzier H. 2016. Experimentally increasing the compliance of titin through RNA binding motif-20 (RBM20) inhibition improves diastolic function in a mouse model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 134:1085–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Green EM, Wakimoto H, Anderson RL, Evanchik MJ, Gorham JM, et al. 2016. A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science 351:617–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jacoby D, Lester S, Owens A, Wang A, Young D, et al. 2018. PIONEER-HCM Cohort B results: reduction in left ventricular outflow tract gradient with mavacamten in symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients Rep., MyoKardia, Inc, San Francisco: http://www.myokardia.com/docs/Pioneer_partB_ACC2018_FINAL.PDF [Google Scholar]

- 92.Planelles-Herrero VJ, Hartman JJ, Robert-Paganin J, Malik FI, Houdusse A. 2017. Mechanistic and structural basis for activation of cardiac myosin force production by omecamtiv mecarbil. Nat. Commun 8:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN, Stauffer BL, et al. 2017. Expert consensus document: mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 14:238–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aubert G, Martin OJ, Horton JL, Lai L, Vega RB, et al. 2016. The failing heart relies on ketone bodies as a fuel. Circulation 133:698–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Phan TT, Abozguia K, Nallur Shivu G, Mahadevan G, Ahmed I, et al. 2009. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is characterized by dynamic impairment of active relaxation and contraction of the left ventricle on exercise and associated with myocardial energy deficiency. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 54:402–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Molina AJ, Bharadwaj MS, Van Horn C, Nicklas BJ, Lyles MF, et al. 2016. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial content, oxidative capacity, and Mfn2 expression are reduced in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction and are related to exercise intolerance. JACC Heart Fail. 4:636–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Greene SJ, Sabbah HN, Butler J, Voors AA, Albrecht-Kupper BE, et al. 2016. Partial adenosine A1 receptor agonism: a potential new therapeutic strategy for heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev 21:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dinh W, Albrecht-Kupper B, Gheorghiade M, Voors AA, van der Laan M, Sabbah HN. 2017. Partial adenosine A1 agonist in heart failure. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 243:177–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xiang F, Huang YS, Zhang DX, Chu ZG, Zhang JP, Zhang Q. 2010. Adenosine A1 receptor activation reduces opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores in hypoxic cardiomyocytes. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol 37:343–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.DeVay RM, Dominguez-Ramirez L, Lackner LL, Hoppins S, Stahlberg H,Nunnari J. 2009. Coassembly of Mgm1 isoforms requires cardiolipin and mediates mitochondrial inner membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol 186:793–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]