Abstract

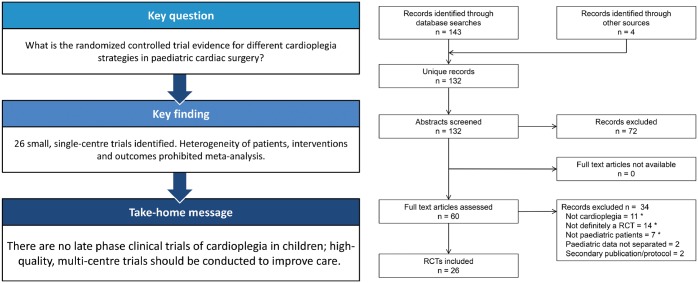

OBJECTIVES

Cardioplegia is the primary method for myocardial protection during cardiac surgery. We conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of cardioplegia in children to evaluate the current evidence base.

METHODS

We searched MEDLINE, CENTRAL and LILACS and manually screened retrieved references and systematic reviews to identify all randomized controlled trials comparing cardioplegia solutions or additives in children undergoing cardiac surgery published in any language; secondary publications and those reporting inseparable adult data were excluded. Two or more reviewers independently screened studies for eligibility and extracted data; the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess for potential biases.

RESULTS

We identified 26 trials randomizing 1596 children undergoing surgery; all were single-centre, Phase II trials, recruiting few patients (median 48, interquartile range 30–99). The most frequent comparison was blood versus crystalloid in 10 (38.5%) trials, and the most common end points were biomarkers of myocardial injury (17, 65.4%), inotrope requirements (15, 57.7%) and length of stay in the intensive care unit (11, 42.3%). However, the heterogeneity of patients, interventions and reported outcome measures prohibited meta-analysis. Overall risk of bias was high in 3 (11.5%) trials, unclear in 23 (88.5%) and low in none.

CONCLUSIONS

The current literature on cardioplegia in children contains no late phase trials. The small size, inconsistent use of end points and low quality of reported trials provide a limited evidence base to inform practice. A core outcome set of clinically important, standardized, validated end points for assessing myocardial protection in children should be developed to facilitate the conduct of high-quality, multicentre trials.

PROSPERO registration

CRD42017080205.

Keywords: Systematic review, Clinical trials, Cardioplegia, Myocardial protection, Paediatric cardiac surgery

INTRODUCTION

The use of cardioplegia has been fundamental to the intracardiac repair of congenital heart lesions for over 40 years. In conjunction with hypothermia, it remains the primary method for myocardial protection against ischaemia–reperfusion injury during cardiac surgery, inducing electromechanical arrest to allow access to a still and bloodless field. Cardioplegic arrest reduces myocardial oxygen uptake to only 10% of the perfused beating heart, and progressive hypothermia leads to a further stepwise reduction [1]. However, myocardial damage still occurs routinely following ischaemia-reperfusion, as demonstrated by the universal release of troponin [2]. Ventricular dysfunction may follow repair of even the simplest lesions [3], manifesting as low cardiac output and requiring inotropic support in the early postoperative period. The immature myocardium exhibits marked differences from the adult heart, including substrate metabolism, calcium handling, insulin sensitivity and antioxidant defence against free radicals [4]. Current cardioplegia techniques are primarily derived from adult or laboratory models and may not be optimal for young children, especially neonates and those with preoperative cyanosis [5–7].

Recent surveys of practice have shown marked variations in the use of commercially available and customized cardioplegia solutions in children in North America [8] and worldwide [9]. The composition, dilution, dose, temperature, route of administration and time interval between doses varied between surgeons and continents, but few surgeons adjusted their technique according to the age of the patient [8]. These findings suggest that the choice of solution is determined primarily by the individual surgeon, institution or country rather than the physiology of the patient and that this may be due to a lack of evidence to support one technique over another. We, therefore, conducted a systematic review of all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of cardioplegia in paediatric cardiac surgery to evaluate the value and quality of the current evidence base.

METHODS

This review was conducted with reference to the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [10, 11] and reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement [12]. All eligibility criteria, search terms and data items were prespecified, and the review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017080205) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Trial eligibility

All randomized and quasirandomized clinical trials comparing cardioplegia solutions or additives in children undergoing cardiac surgery published in any language were included. The definition of a child was based upon the authors’ characterization, and cardioplegia was defined as a solution injected into the cardiac vasculature during surgery with the aim of causing electromechanical arrest.

Trials were excluded if the outcome measures were not related to the use of cardioplegia for myocardial protection. Those including both adults and children were only included if the publication presented the paediatric data separately. Secondary publications, sub-studies or long-term outcomes of previously reported trials were excluded unless the results were specifically related to cardioplegia when the original report was not. Trials published only as a conference abstract or for which all options to obtain the full text publication were exhausted were excluded due to insufficient data for analysis.

Search strategy

We searched international primary research databases (MEDLINE, CENTRAL and LILACS) from inception to 31 October 2017 and reference lists of relevant articles, systematic reviews and meta-analyses to identify all eligible studies. We combined previously validated search strategies to identify RCTs, studies including children and those using cardioplegia as an investigational medicinal product (see Supplementary Material for detailed search terms). For example, to identify RCTs in MEDLINE, we used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials: sensitivity- and precision-maximizing version [10] and to identify studies including children, we adapted the improved Cochrane Childhood Cancer Group filter for PubMed developed by Leclercq et al. [13].

Study selection and data extraction

Abstracts and then full text publications of all identified articles were screened independently by 2 reviewers (I.Y. and N.E.D.) to generate a database of included studies. Data were extracted independently by 2 reviewers (2 of I.Y., A.J.P., N.K.O., C.-R.C. and N.E.D.) from the full trial publication and any published protocols or supplementary material; any assessments of trials in previous systematic reviews were corroborated. A full list of data items, descriptors is available in the Supplementary Material. Any disagreements on study selection or data extraction were resolved by consensus. Non-English language articles were evaluated in conjunction with individuals with a clinical or research methodology background and fluent in that language (C-RC for Chinese, see Acknowledgements).

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used to define the risk of bias for each of the included trials according to the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential threats to validity [11]. Trials were rated as low risk, unclear or high risk of bias for each factor; overall risk of bias was determined for each trial as low (low risk in all domains), high (high risk of bias in 1 or more domains) or unclear (neither of the above).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R (https://www.r-project.org/). All continuous data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical data as counts and percentages where relevant. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between the number of children randomized per trial and the year of publication.

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

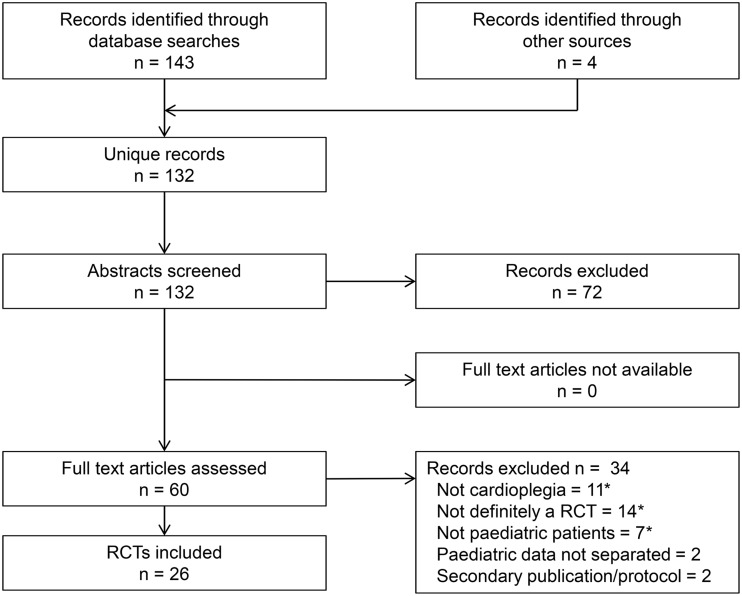

From 132 unique records, we identified 26 RCTs published to 31 October 2017, randomizing 1596 children undergoing surgery with cardioplegic arrest, of whom 1549 (97.1%) were included in analysis of the primary end point. The flow of studies through the systematic review process is documented in Fig. 1. All full text articles were sourced online, via national libraries or directly from the authors; references of included trials are listed in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. Asterisk indicates multiple counting. RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1. All studies were single-centre, Phase II trials, originating from 11 countries, with China (9, 34.6%), Japan (4, 15.4%) and Turkey (3, 11.5%) being the most frequent and only 1 (3.8%) from the USA. Eight (30.7%) trials were published in a language other than English: 7 (26.9%) in Chinese and 1 (3.8%) in Turkish. Trials were most commonly published in specialist cardiothoracic surgery journals (14, 53.8%) with none reaching high-impact cardiovascular or general medical journals.

Table 1:

Characteristics of included trials

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase II, single centre | 26 (100) | Design | |

| Country of origin | Parallel groups | 25 (96.2) | |

| China | 9 (34.6) | Factorial | 1 (3.8) |

| Japan | 4 (15.4) | Randomization | |

| Turkey | 3 (11.5) | Simple unrestricted | 11 (42.3) |

| Iran | 2 (7.7) | Block/stratified | 1 (3.8) |

| UK | 2 (7.7) | Unclear | 14 (53.8) |

| Belgium | 1 (3.8) | Intervention comparisons | |

| India | 1 (3.8) | Blood versus crystalloida | 10 (38.5) |

| Italy | 1 (3.8) | Additives | 6 (23.1) |

| Serbia | 1 (3.8) | Herbal additive | 3 (11.5) |

| Sweden | 1 (3.8) | Non-herbal additive | 3 (11.5) |

| USA | 1 (3.8) | Warm terminal dose (hot shot)a | 3 (11.5) |

| Language of publication | Autologous versus allogenic blooda | 2 (7.7) | |

| English | 18 (69.2) | Custodiol HTK versus St. Thomas’ | 2 (7.7) |

| Chinese | 7 (26.9) | del Nido versus St. Thomas’ | 2 (7.7) |

| Turkish | 1 (3.8) | Warm versus colda | 2 (7.7) |

| Number of arms | Celsior versus St. Thomas’ | 1 (3.8) | |

| 2 | 20 (76.9) | Leucocyte depletion | 1 (3.8) |

| 3 | 6 (23.1) | Potassium concentration | 1 (3.8) |

Multiple counting.

HTK: histidine–tryptophan–ketoglutarate.

The number of children randomized ranged between 20 and 138 with a median of 48 (IQR 30–99). Only 4 (15.4%) trials analysed 50 or more patients per arm, and the median duration of recruitment was 12 months (IQR 6–16.5 months). The median age of patients was 29.5 months (IQR 18.2–54.0 months), and just 21 (1.4%) neonates (confirmed or probable) were included; no trial specifically assessed the use of cardioplegia in neonates. There was no significant correlation between the number of patients recruited per trial and the year of publication (R −0.19). Most surgical procedures were low risk with 255 (16.4%) children undergoing operations with a Risk Adjusted classification for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) score of 3 or above [14], and the mean aortic cross-clamp time across studies was 60 min. The most frequent comparison was blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia in 10 (38.5%) trials followed by various additives in 6 (23.1%) trials (Table 1).

Outcome measures

Thirteen trials (50.0%) had a defined primary end point, one of which (cardiac index) was a clinical outcome; none reported mortality as the primary end point. The most common outcome measures were biomarkers of myocardial injury (17, 65.4%), inotrope requirements (15, 57.7%) and length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU, 11, 42.3%) (Table 2). However, there was marked heterogeneity within end points relating to the metrics of assessment used (Table 3).

Table 2:

Defined outcome measures most frequently reported in included trials

| Outcome measures | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinical | |

| Inotrope requirements | 15 (57.7) |

| Length of stay in the ICU | 11 (42.3) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | 10 (38.5) |

| Length of stay in the hospital | 7 (26.9) |

| Cardiac output/index | 4 (15.9) |

| LV function on echocardiography | 4 (15.9) |

| Non-clinical | |

| Biomarkers of myocardial injury | 17 (65.4) |

| Arterial lactate | 8 (30.8) |

| Myocardial biopsy histology | 5 (19.2) |

| Myocardial biopsy ATP | 4 (15.9) |

| Biomarkers of systemic inflammation | 4 (15.9) |

| Coronary sinus lactate | 3 (11.5) |

ATP: adenosine triphosphate; ICU: intensive care unit; LV: left ventricle.

Table 3:

Outcome metrics for serum biomarkers and inotropes reported in included trials

| Authors | Year | Biomarkers of myocardial injury | Inotropes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matsuda et al. | 1989 | CK-MB: peaka | |

| Mori et al. | 1990 | CK-MB: 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h, total release/activitya | Use |

| Young et al. | 1997 | Inotrope score, total dose 8 h | |

| Hayashi et al. | 2000 | CK-MB: peak (6, 12, 18, 24 h) h-FABP: 50 min | Peak dose |

| Caputo et al. | 2002 | cTnI: AUC 48 h (4, 12, 24, 48 h) | Use, duration |

| Toyoda et al. | 2003 | cTnT: reperfusion, 1, 3, 6, 18 h h-FABP: reperfusion, 1, 2, 3 h | |

| Han et al. | 2004 | ||

| Modi et al. | 2004 | cTnI: AUC 48 h (1, 4, 12, 24, 48 h) | Duration, total dose |

| Amark et al. | 2006 | Total dose 24 h | |

| Cuccurullo et al. | 2006 | ||

| Deng et al. | 2006 | CK-MB: end op, 6, 12, 24, 48 h cTnI: end op, 6, 12, 24, 48 h cTnT: end op, 6, 12, 24, 48 h | |

| Deng et al. | 2007 | ||

| Jin et al. | 2008 | cTnI: 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h | Duration, inotrope score: 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h |

| Deng et al. | 2009 | ||

| Duvan et al. | 2009 | CK-MB: reperfusion, 4, 12, 24, 48 h cTnT: reperfusion, 4, 12, 24, 48 h | Use, duration |

| Zhang et al. | 2009 | Use | |

| Poncelet et al. | 2011 | cTnI: reperfusion, 6, 12, 24 h | Use |

| Liu et al. | 2012 | cTnI: 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 ha | Inotrope score: 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h |

| Cheng et al. | 2013 | CK: 30 min, 24 h | |

| Korun et al. | 2013 | ||

| Ma et al. | 2013 | CK-MB: end CPB cTnI: end CPB | Use |

| Nezafati et al. | 2013 | ||

| Kuşlu et al. | 2015 | CK-MB: end op, 4, 16, 24, 48 h cTnI: end op, 4, 16, 24, 48 ha | Peak dose, dose: end op, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48 h |

| Mimic et al. | 2016 | cTnI: reperfusion, 1, 4, 12, 24 ha | Level 24 h, duration |

| Gorjipour et al. | 2017 | cTnI: reperfusion, 24 h | |

| Talwar et al. | 2017 | cTnI: end CPB, 24 h | VIS: 1, 2, 3, 4 days |

For full references of the included trials, see Supplementary Material.

Defined primary outcome.

AUC: area under the curve; CK: creatine kinase; CK-MB: creatine kinase MB isoenzyme; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; cTnI: cardiac troponin I subunit; cTnT: cardiac troponin T subunit; h-FABP: heart-type fatty acid binding protein; VIS: vasoactive inotrope score.

Serum biomarker assays of myocardial injury were cardiac troponin (cTn) in 13 (50.0%), specifically the cTn-I subunit in 11 (42.3%) and cTn-T subunit in 3 (11.5%); serum creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) in 8 (30.8%) and heart-type fatty acid binding protein in 2 (7.7%). These measures were inconsistently reported as concentrations at time points from reperfusion to 48 h, peak value, total release/activity and area under the time–concentration curve (AUC); scheduling of sample collection was variable and timed from reperfusion, end of cardiopulmonary bypass, end of surgery or arrival in the ICU. Similarly, inotrope use was reported as binary need for support, dose at the end of surgery or postoperative intervals, maximal dose, total dose in the first 24 h, duration of use and various inotrope scores over differing time periods. The heterogeneity of patients, interventions and reported outcome measures thereby prohibited meta-analysis. Only short-term outcomes up to discharge or 30 days were reported.

Quality of trials

Regarding standards for the conduct and reporting of clinical trials [15], 4 (15.4%) performed a sample size calculation, 2 (7.7%) were prospectively registered on a publicly accessible trial database and 2 (7.7%) published a CONSORT flow diagram. None of the 26 trials were overseen by an independent Data Monitoring Committee, and none were stopped early or extended.

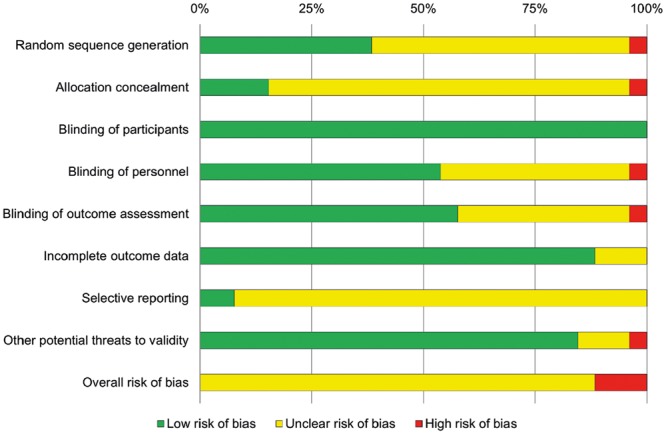

Risk of bias assessment for each of the 8 domains and overall is shown in Fig. 2. Overall risk of bias was high in 3 (11.5%) trials, unclear in 23 (88.5%) and low in none; the high proportion of unclear resulted from poor reporting of randomization and masking procedures, and an inability to exclude selective reporting due to a lack of trial registration or published protocol.

Figure 2:

Cochrane risk of bias scores for included trials.

DISCUSSION

RCTs represent the gold standard in evaluating healthcare interventions through rigorous testing of a predefined protocol and minimization of bias [15]. However, in this systematic review of the published literature, we identified only 26 RCTs of cardioplegia in paediatric cardiac surgery; these were exclusively single-centre, Phase II trials that were rarely prospectively registered, recruited small number of patients, lacked independent oversight and were not reported to international standards [15, 16]. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of patients, interventions and reported outcome measures across trials precluded the pooling of results for meta-analysis. Of concern is the finding that studies included few neonates, in whom myocardial metabolism and cellular homeostasis differ from the more mature heart, and the effects of cardioplegia are less well understood [4]. As a result, these trials provide a limited evidence base to support clinical decision-making on cardioplegia, a technique which is so fundamental to the surgical management of children with congenital heart disease. Although all cardioplegia solutions are efficacious in arresting the heart, differences in their effectiveness to reduce ischaemia–reperfusion injury and, therefore, improve outcomes are unknown.

Our findings reflect those of a previous, more limited meta-analysis of cardioplegia trials in children. Fang et al. [17] compared the efficacy of blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia and identified 5 RCTs published in English prior to mid-2013, recruiting 358 children in total. They found no difference in cTn-I release at 4–6, 12 or 24 h (3 trials), duration of ventilation (3 trials) or length of ICU stay (4 trials). Only blood lactate following cardiopulmonary bypass (4 trials) was significantly lower in the blood cardioplegia group, but this difference was prejudiced by 1 study, without which there was no effect. Inotrope use was reported in all 5 trials, but the reviewers were unable to pool data due to the diverse metrics used. Risk of bias was assessed using the modified Jadad scale, a flawed method of quality assessment, with all trials classified as ‘high quality’ despite only 1 scoring >5 on the 8-point scale. They concluded that there was no evidence of improvement in myocardial injury or clinical outcomes but were limited by the small number of patients and variability in age, preoperative cyanosis and techniques used. Similarly, Mylonas et al. [18] recently identified many non-randomized or retrospective studies on paediatric cardioplegia but few RCTs, a finding that is commonplace throughout the global paediatric cardiac surgery literature. In a recent systematic review of RCTs published since 2000, we identified few late-phase clinical trials; most were small, single-centre studies of low value, uncertain quality and at risk of systematic bias [19]. This lack of evidence to guide clinical practice fosters uncertainty and predisposes to variability in patient care.

Low cardiac output syndrome following surgery is the commonest premorbid complication in children and the most frequent seminal event leading to death [20]. The ubiquitous release of troponin following aortic cross-clamping in children demonstrates that myocardial injury occurs routinely and is, therefore, not a problem solved [2, 4]. Myocardial protection remains an area of active research; 18% of recent clinical trials in paediatric cardiac surgery evaluated cardioplegia, ischaemic conditioning or other drugs to reduce myocardial injury [19]. However, the wide range of variables in cardioplegia technique has led to a potpourri of studies evaluating different aspects of practice. Of the papers identified in this review, blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia was the most common comparison (10, 38.5%) but was often combined with other differences between groups, such as warm versus cold or autologous versus allogenic blood, making direct comparison between studies more difficult and limiting meta-analysis. This variability in techniques evaluated by clinical trials reflects the current state of clinical practice; the second most commonly used formulations of cardioplegia for children in North America are customized solutions (34%) unique to each centre [8], essentially a ‘none of the above’ homebrew, emphasizing the lack of evidence for an optimal cardioplegia solution. As such, the widespread adherence to local solutions may also provide a barrier to conducting multicentre clinical trials.

To facilitate the synthesis of findings from multiple studies, clinical trials must report valid and comparable outcome measures. We found marked variation in the reporting of end points between trials with inconsistent use of metrics to evaluate the same outcome (Table 3). Biomarkers of myocardial injury were the most commonly used outcome measure but included 1 or more of serum troponin-I, troponin-T, CK-MB and heart-type fatty acid binding protein, measured at varying time points up to 48 h, and variably reported as measured concentrations, peak or AUC. This disparity reflects the absence of a standardized method for reporting biomarker release after ischaemia–reperfusion in children as it is unknown which metric has the greatest discriminatory power. Following coronary surgery in adults, cumulative AUC troponin at 72 h has been shown to best predict mid-term mortality [21]. However, obtaining blood samples even up to 48 h is more problematic in children, especially with expedited removal of venous lines during an uneventful recovery [22]. Newer measures of myocardial injury, such as heart-type fatty acid binding protein and high-sensitivity troponin, may have an earlier peak and greater positive predictive value [23–25] but currently lack validation in this cohort [26]. Other outcome measures also differed in their definition, timing and measurement. Inotropic support in the early postoperative period was reported using various metrics of dose, duration or a combination through an inotrope score; recently, maximum vasoactive-inotropic score has been identified as the optimal measure of pharmacological cardiovascular support after cardiac surgery in infants and is strongly associated with morbidity and mortality [27]. Length of stay in the ICU was usually recorded as actual time elapsed rather than assessed against objective criteria such as fitness for discharge. Furthermore, all trials reported only short-term end points with no functional or long-term outcomes.

Heterogeneity of outcome measures is a common problem in systematic reviews and limits the ability to conduct meta-analyses of pooled data. The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative is an international effort to develop core outcome sets for clinical trials, defined as ‘the minimum that should be measured and reported in all clinical trials of a specific condition’ [28]. However, there are currently no core outcome sets relevant to any aspect of children’s heart surgery registered on the COMET database. End points such as vasoactive inotrope score [27] and duration of postoperative mechanical ventilation [29] have been validated in large datasets and should form the basis of such an endeavour. A set of standardized, evidence-based end points would have enabled selection of the same metrics across trials, reduced the risk of outcome reporting bias and increased the value of individual studies by facilitating evidence synthesis. To approve new drugs, the US food and drug administration (FDA) looks for end points that are clinically meaningful and ideally measure directly how a patient ‘feels, functions or survives’ [30]; however, none of the trials reported outcomes beyond discharge or 30 days, and there is little evidence to correlate perioperative variables to the long-term functional outcomes that are most important to patients, such as exercise tolerance and quality of life.

The strengths of this systematic review include the comprehensive search strategy, independent review procedures and obtainment of the full text of all potential articles in all languages. The limitations include: a risk of reporting bias, although unpublished studies would be expected to be of lower value; an inability to perform any meta-analyses to inform clinical practice due to the paucity of comparable studies; and limiting the scope to RCTs, which are not the only source of valuable evidence to inform clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

This comprehensive systematic review demonstrates that the current literature on cardioplegia in children contains no late phase trials. The small size, inconsistent use of end points and low quality of reported trials provides a limited evidence base to inform clinical practice; neonates were particularly poorly represented. This lack of evidence combined with marked variations in care [8, 9] demonstrates clinical equipoise and the need for high-quality, late phase, multicentre clinical trials to determine which of the current cardioplegic solutions provide the best myocardial protection for defined patient groups. An agreed core outcome set of clinically important, standardized, validated end points for assessing myocardial protection in children should be developed to facilitate the conduct of such trials and the meta-analysis of pooled data. Improving our understanding of how these perioperative end points relate to long-term functional outcomes will be key to improving myocardial protection, especially in those who have cumulative exposure to ischaemia reperfusion through multiple operations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are most grateful to Angela Reed and Stuart Purchase in the Library at Birmingham Children’s Hospital for locating many of the articles. They thank Safak Alpat, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Canada, for translation from Turkish.

Funding

N.E.D. is supported by an Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship from the British Heart Foundation [FS/15/49/31612].

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Buckberg GD, Brazier JR, Nelson RL, Goldstein SM, McConnell DH, Cooper N.. Studies of the effects of hypothermia on regional myocardial blood flow and metabolism during cardiopulmonary bypass. I. The adequately perfused beating, fibrillating and arrested heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1977;73:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mildh LH, Pettilä V, Sairanen HI, Rautiainen PH.. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in pediatric open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:1643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaturvedi RR, Lincoln C, Gothard JW, Scallan MH, White PA, Redington AN. et al. Left ventricular dysfunction after open repair of simple congenital heart defects in infants and children: quantification with the use of a conductance catheter immediately after bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doenst T, Schlensak C, Beyersdorf F.. Cardioplegia in pediatric cardiac surgery: do we believe in magic? Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1668–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. del Nido PJ, Mickle DA, Wilson GJ, Benson LN, Weisel RD, Coles JG. et al. Inadequate myocardial protection with cold cardioplegia arrest during repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;95:223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Imura H, Caputo M, Parry A, Pawade A, Angelini GD, Suleiman MS.. Age-dependent and hypoxia-related differences in myocardial protection during paediatric open heart surgery. Circulation 2001;103:1551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Najm HK, Wallen WJ, Belanger MP, Williams WG, Coles JG, Van Arsdell GS. et al. Does the degree of cyanosis affect myocardial adenosine triphosphate levels and function in children undergoing surgical procedures for congenital heart disease? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;119:515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotani Y, Tweddell J, Gruber P, Pizarro C, Austin EH 3rd, Woods RK. et al. Current cardioplegia practice in pediatric cardiac surgery: a North American multiinstitutional survey. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harvey B, Shann KG, Fitzgerald D, Mejak B, Likosky DS, Puis L. et al. International pediatric perfusion practice: 2011 survey details. J Extra Corpor Technol 2012;44:186–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J.. Searching for studies In: Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: Wiley, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org (21 February 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC.. Assessing risk of bias in included studies In: Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: Wiley, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org (21 February 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J 2009;339:b2535.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leclercq E, Leeflang MM, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC.. Validation of search filters for identifying pediatric studies in PubMed. J Pediatr 2013;162:629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Spray TL, Moller JH, Iezzoni LI.. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;123:110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D.. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Br Med J 2010;340:c332.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hartling L, Wittmeier KDM, Caldwell P, van der Lee H, Klassen TP, Craig JC. et al. StaR Child Health: developing evidence-based guidance for the design, conduct, and reporting of pediatric trials. Pediatrics 2012;129:S112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fang Y, Long C, Lou S, Guan Y, Fu Z.. Blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia for pediatric cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Perfusion 2015;30:529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mylonas KS, Tzani A, Metaxas P, Schizas D, Boikou V, Economopoulos KP.. Blood versus crystalloid cardioplegia in pediatric cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Cardiol 2017;38:1527–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drury NE, Patel AJ, Oswald NK, Chong C-R, Stickley J, Barron DJ. et al. Randomised controlled trials in children’s heart surgery in the 21st century: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;53:724–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaies M, Pasquali SK, Donohue JE, Dimick JB, Limbach S, Burnham N. et al. Seminal postoperative complications and mode of death after pediatric cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:628–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ranasinghe AM, Quinn DW, Richardson M, Freemantle N, Graham TR, Mascaro J. et al. Which troponometric best predicts midterm outcome after coronary artery bypass graft surgery? Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Modi P, Suleiman MS, Reeves B, Pawade A, Parry AJ, Angelini GD. et al. Myocardial metabolic changes during pediatric cardiac surgery: a randomized study of 3 cardioplegic techniques. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hasegawa T, Yoshimura N, Oka S, Ootaki Y, Toyoda Y, Yamaguchi M.. Evaluation of heart fatty acid-binding protein as a rapid indicator for assessment of myocardial damage in pediatric cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:1697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aĝirbaşli M, Nguyen ML, Win K, Kunselman AR, Clark JB, Myers JL. et al. Inflammatory and hemostatic response to cardiopulmonary bypass in pediatric population: feasibility of seriological testing of multiple biomarkers. Artif Organs 2010;34:987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Westermann D, Neumann JT, Sörensen NA, Blankenberg S.. High-sensitivity assays for troponin in patients with cardiac disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017;14:472–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evers ES, Walavalkar V, Pujar S, Balasubramanian L, Prinzen FW, Delhaas T. et al. Does heart-type fatty acid binding protein predict clinical outcomes after pediatric cardiac surgery? Ann Pediatr Card 2017;10:245–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaies MG, Jeffries HE, Niebler RA, Pasquali SK, Donohue JE, Yu S. et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score is associated with outcome after infant cardiac surgery: an analysis from the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium and Virtual PICU system registries. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15:529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials Initiative. http://www.comet-initiative.org (21 February 2017, date last accessed).

- 29. Gaies M, Werho DK, Zhang W, Donohue JE, Tabbutt S, Ghanayem NS. et al. Duration of postoperative mechanical ventilation as a quality metric for pediatric cardiac surgical programs. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;105:615–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Temple RJ. A regulatory authority’s opinion about surrogate endpoints In: Nimmo WS, Tucker GT (eds). Clinical Measurement in Drug Evaluation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.