Abstract

Background and Objectives

Somatic mutations in the calreticulin gene (CALR) are detected in approximately 70% of patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary or secondary myelofibrosis (MF), lacking the JAK2 and MPL mutations. To determine the prevalence of CALR frameshift mutations in a population of MPN patients of Greek origin, we developed a rapid low-budget PCR-based assay and screened samples from 5 tertiary Haematology units. This is a first of its kind report of the Greek patient population that also disclosed novel CALR mutants.

Methods

MPN patient samples were collected from different clinical units and screened for JAK2 and MPL mutations after informed consent was obtained. Negative samples were analyzed for the presence of CALR mutations. To this end, we developed a modified post Real Time PCR High-Resolution Melting Curve analysis (HRM-A) protocol. Samples were subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Results

Using this protocol we screened 173 MPN, JAK2 and MPL mutation negative, patients of Greek origin, of whom 117 (67.63%) displayed a CALR exon nine mutation. More specifically, mutations were detected in 90 out of 130 (69.23%) essential thrombocythaemia cases (ET), in 18 out of 33 (54.55%) primary myelofibrosis patients (pMF) and in 9 out of 10 (90%) cases of myelofibrosis secondary to ET (post-ET sMF). False positive results were not detected. The limit of detection (LoD) of our protocol was 2%. Furthermore, our study revealed six rare novel mutations which are to be added in the COSMIC database.

Conclusions

Overall, our method could rapidly and cost-effectively detect the mutation status in a representative cohort of Greek patients; the mutation make-up in our group was not different from what has been published for other national groups.

Keywords: Myeloproliferative Diseases, Thrombocythemia, Myelofibrosis, Calreticulin, Jak2, MPL, Mutation

Introduction

Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) include polycythaemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythaemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (pMF).1 The molecular basis of these disorders was partly elucidated in 2005 with the identification of the JAK2V617F mutation in the majority of PV patients and in about 60% of those with ET and MF.2–6 It was later reported that somatic mutations of JAK2 exon 12 are present in the remaining PV patients,7 while mutations of MPL exon 10 were present in about 5% of the ET and MF cases.8 2008 WHO definition of MPNs includes JAK2V617F or MPL exon ten mutations as a major criterion for disease diagnosis.9 Beyond these two culprits, somatic mutations in the CALR gene that encodes for calreticulin were identified in 2013 in about 20–25% of patients with ET and MF10,11 and were subsequently incorporated into the 2016 WHO diagnostic criteria.12 Determination of CALR mutations is relevant not only for their diagnostic contribution12 but also for their prognostic significance as well.13–16

CALR mutations are deletion or insertion events or a combination of both within the DNA sequence of the last exon (exon 9) of the gene. The two most common mutations are either a 52-bp deletion (Type-1; c.1099_1150del;L367fs*46; 45–55% of the cases) or a 5-bp insertion (Type-2; c.1154_1155insTTGTC; K385fs*47; 32–42% of the cases). The remaining 15% of the cases comprise other deletions or insertions or a combination of both that are either unique or found in a small number of patients.10,11,17 All CALR mutations result in a +1bp frameshift, leading to the coding of a novel amino acid peptide sequence distal to the site of the mutation that consequently generates a novel C-terminus at the protein level.10,11

The high incidence and specificity of CALR mutations in ET and MF make inevitable the need of incorporating rapid and sensitive methodologies in the diagnostic work-up of MPNs. In the relatively similar case of JAK2, improved PCR methods, have pushed the JAK2V617F mutation limit of detection (LoD) down to a burden of only 1–3%, which has been considered sufficient for the clinical correlation to PV. Such LoD levels should also be attained with the available technologies in the case of CALR.18

Detection of CALR exon nine mutations can be achieved by several methods such as Sanger sequencing, fragment analysis, high resolution melting curve analysis (HRM-A), TaqMan-based Real-Time PCR and targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS).10,11,19–22 Targeted NGS provides the best LoD and is the most robust technique;21 however, it is still a costly approach with a long turn-around time, which makes it impractical for routine diagnostic services. HRM-A, is a well-established method for the detection of gene polymorphisms and mutations, by measuring changes in the melting point of DNA duplex.23

In this report, we describe a rapid and sensitive HRM-A protocol, which we developed for the detection of CALR exon nine mutations using the LightCycler cobas 4800 platforms (ROCHE Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, US). Our assay was first applied in a small cohort of MF patients; subsequently, when thoroughly validated, it was used for the study of ET and MF samples from several tertiary health care centres in Greece, thus providing reliable data concerning the frequency of CALR mutations within the Greek population and even disclosing a few novel mutations.

Material and Methods

Patient diagnosis was based on the WHO 2008 criteria.1,9 CALR mutational analysis was performed in 130 patients with ET and 43 patients with MF who were negative for the JAK2V617F and MPLW515L/K mutations, as well as in 19 patients with secondary thrombocytosis.

The study protocol was approved by the Internal Review Boards of all participating Institutes; written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was conducted in accordance with the current version of the Helsinki Declaration.

DNA was extracted by standard procedures after isolation of total leukocytes from peripheral blood or bone marrow following red cell lysis. All samples were investigated for the presence of the JAK2V617F and the MPLW515L/K mutations. The JAK2V617F mutation was detected using a tetra-primer amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay with a sensitivity of 1% as previously described.4 The MPLW515L/K mutations were detected using an allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) assay with a sensitivity of 1% as previously described.24

HRM analysis assay design

The HRM analysis assay was performed using the LightCycler cobas 4800 platform (ROCHE Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, US). Oligonucleotide primers were designed using the Oligo7 Primer Analysis Software v.7.0.5.7 (Molecular Biology Insights Inc, Colorado Springs, CO, US) to flank all CALR exon 9 variants reported in MPNs. Primer sequences were CALRe9HF: 5′-AGGCAGCAGAGAAACAAATGAA-3′ and CALRe9HR: 5′-TCTACAGCTCGTCCTTGGC-3′, and the amplicon size was 204 bp (GenBank: NG_029662.1). Ten nanograms of DNA was amplified in a final volume of 10μL containing 1× LightCycler 480 High-Resolution Melting Master Mix (ROCHE Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, US), 1.0μM of the CALRe9HF, 0.2μM of the CALRe9HR and 2.5 mM MgCl2.

The cycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15s, 67°C for 30s and 72°C for 15s. The high resolution melting program included denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, re-naturation at 40°C for 1 min and melting from 65°C to 95°C, with a ramp of 0.03°C per second and 17 fluorescent acquisitions per degree centigrade.

All samples were analysed in duplicate. Two samples of normal individuals (CALR wild-type), one positive control for CALR Type-1 and one positive control for CALR Type-2 were included in each experiment. The analysis was done with the Light Cycler 480 Gene Scanning Software v.1.5.1.74 (ROCHE Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, US). Melting profiles were normalized, grouped and displayed as fluorescence versus temperature plots. Normalization bars were set between 81.5 and 82.0°C for the leading range and 88.0–88.5°C for the tailing range. The threshold for the melting temperature (Tm) shift was set at 10. The settings were optimized to a sensitivity value of 0.4 on the analysis software.

Wild-type and mutated samples were defined as negative and positive controls respectively in the analysis. Melting curve analysis is based on the differences in melting curve shape of each sample, hence clustering the samples into groups based on the internal software calculation.

Sanger Sequencing

All patients were screened for CALR exon 9 mutations spanning codons 1054–1254 by Sanger sequencing at an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, US). Sanger sequencing was performed on a broader genomic area than the one used for the HRM-A. The PCR primer sequences were CALRe9SF: 5′-CCAACGATGAGGCATACGCT-3′ and CALRe9SR: 5′-ATCCACCCCAAATCCGAACC-3′ and the amplicon size was 469 bp (GenBank: NG_029662.1). PCR products were cleaned using the QiaQuick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bidirectional sequencing was performed using the BigDye Terminator, v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The analysis was performed using the Chromas v.2.4.3 (Technelysium Pty Ltd, South Brisbane, QLD, AU) software.

Results

HRM analysis for CALR exon 9 mutations

Table 1 summarizes our results. Of the 173 ET and MF patients analysed using our HRM-A protocol, 117 (67.63%) displayed a CALR exon 9 mutation; the incidence of this finding in the ET and MF cohorts was quite similar, comprising of 69.23% in the ET (90 out of 130) and 62.79% in the MF (27 out of 43) group of patients. More specifically, the latter group includes 33 pMF and 10 secondary post-ET MF, of which 54.55% (18 out of 33) and 90% (9 out of 10) carried CALR exon 9 mutations, respectively. In contrast, all 19 patients with secondary thrombocytosis were CALR negative.

Table 1.

Distribution of CALR exon 9 mutations detected in the cohorts of Greek ET and MF patients.

| Essential thrombocythaemia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-1 | Type-1 like | Type-2 | Type-2 like | Complex type | Mutations detected | Samples | |

| n | 46 | 6 | 34 | 1 | 3 | 90 | 130 |

| % | 51.11 * | 6.67 * | 37.78 * | 1.11 * | 3.33 * | 69.23 ** | |

| Primary myelofibrosis | |||||||

| Type-1 | Type-1 like | Type-2 | Type-2 like | Complex type | Mutations detected | Samples | |

| n | 13 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 33 |

| % | 72.22 * | 11.11 * | 16.67 * | 0.00 * | 0.00 * | 54.55 ** | |

| Myelofibrosis secondary to ET | |||||||

| Type-1 | Type-1 like | Type-2 | Type-2 like | Complex type | Mutations detected | Samples | |

| n | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| % | 90.00 ** | ||||||

Percentage of mutation subtypes versus overall mutations detected.

Percentage of mutations detected versus samples under investigation.

Of the 90 ET patients with HRM positive curves, 46 were Type-1 (L367fs*46), 6 were Type-1-like (E364fs*55, L367fs*50, L367fs*52, D373fs*47, K375fs*49 and K377fs*47), 34 were Type-2 (K385fs*47), 1 was Type-2-like (E386fs*46) and 3 showed complex mutations consisting of D373fs*56, D373fs*51 and K377fs*55. Of the 27 MF patients with HRM positive curves, 16 were Type-1 (L367fs*46), 3 were Type-1-like (L367fs*52 and K377fs*47), 7 were Type-2 (K385fs*47) and 1 showed a complex mutation (E379fs*47).

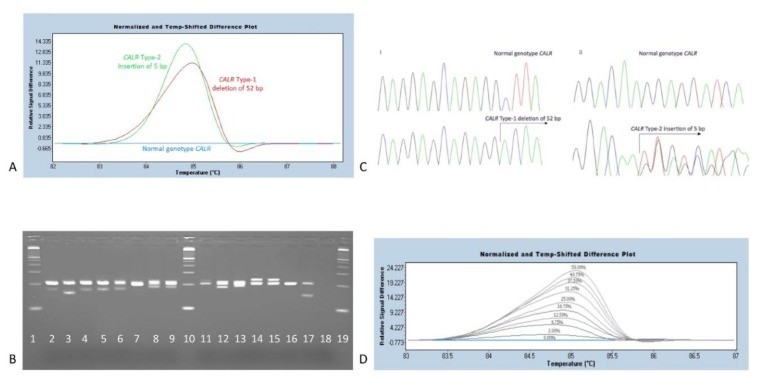

Table 2 shows the coding sequence alterations (at the cDNA level) of the detected CALR exon 9 mutations. Most of them are already known and included in the most recent database of the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC v85, as of May 8th, 2017),25 while six are reported for the first time. As expected, most commonly found mutations were those of Type-1 and Type-2 (Figure 1A).

Table 2.

Common and rare CALR exon 9 mutations detected in the cohorts of Greek ET and MF patients. Registration order according to increasing start site of mutation within the coding sequence. Mutations # 3, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 11 are novel and (as of May 8, 2017) are not included in the COSMIC v85 database.

| Coding sequence alteration (cDNA level) | Aminoacid sequence alteration | Recurrence | Previously reported | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.1091_1124del34 | p.E364fs*55 | 1 | YES |

| 2 | c.1092_1143del52 | p.L367fs*46 | 62 | YES |

| 3 | c.1094_1130del37 | p.L367fs*50 | 1 | NO |

| 4 | c.1098_1131del34 | p.L367fs*52 | 3 | YES |

| 5 | c.1116_1146del31 | p.D373fs*47 | 1 | YES |

| 6 | c.1118_1125>CTTG | p.D373fs*56 | 1 | NO |

| 7 | c.1118_1140>CGTT | p.D373fs*51 | 1 | NO |

| 8 | c.1122_1140del19 | p.K375fs*49 | 1 | YES |

| 9 | c.1129_1132>TTTTGCTTA | p.K377fs*55 | 1 | NO |

| 10 | c.1129_1147del19 | p.K377fs*47 | 2 | NO |

| 11 | c.1131-1151>GGAGTGTC | p.E379fs*47 | 1 | NO |

| 12 | c.1154_1155insTTGTC | p.E385fs*47 | 41 | YES |

| 13 | c.1154_1155insATGTC | p.K386fs*46 | 1 | YES |

Figure 1.

A. HRM-A curves after normalization of temperature and fluorescence data, using the LightCycler 480 SW 1.5.1 software (ROCHE Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, US). The two most common CALR exon 9 mutations detected, are Type-1 deletion (L367fs*46) and Type-2 insertion (K385fs*47). These are grouped separately, due to variations in the pattern of their melting curves. Both melting curves differ significantly compared to the normal genotype sample. Each Type-1-like, Type-2-like and complex mutation identified provided a unique melting curve pattern, that diverges from a normal control. B. Agarose gel 3% dense electrophoresis of PCR products. Left to right: line 1, MW marker; line 2, a 34 bp deletion (E364fs*55); line 3, a Type-1 deletion of 52 bp (L367fs*46); line 4, a 37 bp deletion (L367fs*50); line 5, a 34 bp deletion (L367fs*52); line 6, a 31 bp deletion (D373fs*47); line 7, a complex mutation (D373fs*56); line 8, a complex mutation (D373fs*51); line 9, a 19 bp deletion (K375fs*49); line 10, the MW marker; line 11, a complex mutation (K377fs*55); line 12, a 19 bp deletion (K377fs*47); line 13, a complex mutation (E379fs*47); line 14, a 5 bp insertion (E386fs*46); line 15, a Type-2 insertion of 5 bp (K385fs*47); line 16, a normal CALR genotype sample; line 17, a MARIMO cell line DNA sample carrying a 61 bp deletion (L367fs*43) which was initially used as a study reference; line 18, a Non Template Control sample (NTC); line 19 the MW marker. A 100 bp molecular-weight size marker (MW) was used as a DNA ladder (Thermo-Fischer Scientific). C. Sanger sequencing chromatograms for sequence identification of the HRM-A previously detected CALR mutations. i. Top to bottom: a CALR normal genotype sample and a common Type-1 deletion (L367fs*46). ii. Top to bottom: a CALR normal genotype sample and a Type-2 insertion (K385fs*47). D. LoD analysis of the designed HRM-A protocol. A sample harboring a Type-1 deletion mutation (L367fs*46) was used as a reference. Starting at 50% of mutation allele burden, as determined after Sanger sequencing analysis, we ended up detecting as low as 2% of mutant alleles, through serial dilutions.

Following HRM-A, PCR products were analysed in 3% agarose gel to confirm that the detected melting curve pattern, diverging from normal genotype control samples, actually belongs to a CALR exon 9 mutation (Figure 1B). The 204 bp band corresponds to the wild-type CALR gene, while additional bands are evidence of CALR mutations.

Sanger sequencing analysis of CALR exon 9 mutations

Sanger sequencing analysis was performed in all cases; results were fully concordant with those obtained by the HRM-A technique (Figure 1C).

Limit of Detection of HRM analysis for CALR exon 9 mutations

In order to assess the LoD of the assay, we performed serial dilutions of a patient’s sample carrying a CALR Type-1 mutation (52-bp deletion) and displaying a mutant allele burden of approximately 50% according to sequencing analysis. Serial dilutions were made up to 1% of the mutant in wild-type DNA. The CALR mutant could be detected in up to 2% dilution (Figure 1D).

Discussion

Recent methodological advances have shown that somatic mutations in the CALR gene occur in 20% to 25% of patients with ET and MF10,11 and are now incorporated into the most recent revision of the WHO diagnostic criteria.12 Determination of CALR mutations is essential for the diagnostic workup12 and has an impact on the assessment of prognosis.13–15

CALR mutation analysis is carried out with several methods including Sanger sequencing,26 fragment analysis,27 HRM-A,19 Real Time PCR using TaqMan probes28 and NGS21 with each one of these methods having their specific advantages and drawbacks. Sanger sequencing and fragment analysis have limited sensitivity (in the range of 10–25% and 5–10% respectively), while the NGS technology presents the lowest LoD (1–1.5%) but is costly and time-consuming for routine use, at present.21,29

More specifically, compared to NGS, our HRM-A protocol can be completed within a few hours of sample collection, providing fast turn-around times. On the other hand, NGS library preparation and sequencing require a minimum of 2 days for completion, without taking into account the downstream time-consuming analytical steps and the prerequisite of multiplexing more than one samples for cost-effectiveness. The latter is a major obstacle for labs with small sample load. In addition, the NGS output is such that aiming solely at the CALR mutation, would be a waste of resources. To fully exploit the capabilities of NGS, clinical laboratories either need a significant load of samples on a routine basis or the simultaneous analysis of more than one genomic region. For all other occasions, HRM-A offers a relatively simple but equally reliable technique that can support the daily routine of individual samples with fast turn-around times.

Other platforms that offer equally satisfactory sensitivity levels to HRM-A are TaqMan-based assays. The classical method uses fluorescently labeled probes, that bind specific DNA sequences. In this way, potentially unwanted PCR by-products can be ignored during analysis, thus allowing for less stringent PCR conditions and primer design. However, the use of nucleotide probes increases expenses and limits the detection to previously determined mutations only. On the contrary, the HRM-A approach is less costly and also permits the detection of novel mutations. A potential drawback of the HRM-A method is the use of fluorescent molecules that bind double-stranded nucleic acids in a non-specific manner. This feature may lead to confusing detection signals, due to potential secondary amplicons, unless experimental settings are optimized in a way that allows the amplification of specific products. This prerequisite has been fulfilled in our protocol design.

In this communication, we propose an optimized HRM-A protocol, which can identify CALR exon 9 mutations on the basis of the differential plots that clearly discriminate mutant from wild-type samples. Moreover, this version can efficiently classify Type-1 and Type-2 common mutations and appears to prevent the detection of false-positive results, in contrast to earlier reports.21 These characteristics are attributed to the carefully designed highly specific primers, along with finely tunned primer annealing temperature (Ta) and PCR cycling conditions. Our modification also allowed prompt detection of novel mutations through the appearance of variable changes in the melting curve profile of undetermined genotype samples, which were then further investigated using Sanger sequencing. In our experiments, the LoD of mutated DNA in a wild-type background was 2%, which is considered fully acceptable (≥2%), marginally lower than that previously reported when using the same technique (3%) and not substantially different than the respective TaqMan assays, where LoD varies between 1–3%.19,28

In order to validate our standardized technique, we applied it in a study of a large cohort of Greek ET and MF patients. We observed that neither the overall frequency of the CALR exon 9 mutations nor their distribution in the Greek ET and MF patients was substantially different from those reported in similar surveys from other European institutes.10,11,30,31 In addition, we identified six novel mutations, which are to be added in the COSMIC database.

Conclusions

The proposed modification of the HRM-A technique is considered reliable and has proven useful for the large-scale survey of the CALR exon 9 mutations across the Greek ET and MF patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th Ed. Lyon: IARC; 2008. [Aug. 2018]. pp. 40–50. available at: http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?codlan=1&codcol=70&codcch=4002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, Vassiliou GS, Bench AJ, Boyd EM, Curtin N, Scott MA, Erber WN, Green AR Cancer Genome Project. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. [Aug. 2018];Lancet. 2005 365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)71142-9/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, Garçon L, Raslova H, Berger R, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Villeval JL, Constantinescu SN, Casadevall N, Vainchenker W. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. [Aug. 2018];Nature. 2005 434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AV, Kreil S, Zoi K, Waghorn K, Curtis C, Zhang L, Score J, Seear R, Chase AJ, Grand FH, White H, Zoi C, Loukopoulos D, Terpos E, Vervessou EC, Schultheis B, Emig M, Ernst T, Lengfelder E, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Oscier D, Silver RT, Reiter A, Cross NC. Widespread occurrence of the JAK2V617F mutation in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2005 106(6):2162–2168. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1320. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/106/6/2162.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Cazzola M, Skoda RC. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. [Aug. 2018];N Engl J Med. 2005 352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine RL, Loriaux M, Huntly BJ, Loh ML, Beran M, Stoffregen E, Berger R, Clark JJ, Willis SG, Nguyen KT, Flores NJ, Estey E, Gattermann N, Armstrong S, Look AT, Griffin JD, Bernard OA, Heinrich MC, Gilliland DG, Druker B, Deininger MW. The JAK2V617F activating mutation occurs in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia, but not in acute lymphoblastic leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2005 106(10):3377–3379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1898. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/106/10/3377/tab-figures-only. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Erber WN, McMullin MF, Harrison CN, Warren AJ, Gilliland DG, Lodish HF, Green AR. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. [Aug. 2018];N Engl J Med. 2007 356(5):459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202. available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa065202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, McDowell E, Ebert BL, Gozo M, Cuker A, Wernig G, Moore S, Galinsky I, DeAngelo DJ, Clark JJ, Lee SJ, Golub TR, Wadleigh M, Gilliland DG, Levine RL. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. [Aug. 2018];PLoS Med. 2006 3(7):e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, Harris NL, Le Beau MM, Hellström-Lindberg E, Tefferi A, Bloomfield CD. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2009 114(5):937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. available at: ù http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/early/2009/04/08/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, Nivarthi H, Rumi E, Milosevic JD, Them NC, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pietra D, Chen D, Vladimer GI, Bagienski K, Milanesi C, Casetti IC, Sant’Antonio E, Ferretti V, Elena C, Schischlik F, Cleary C, Six M, Schalling M, Schönegger A, Bock C, Malcovati L, Pascutto C, Superti-Furga G, Cazzola M, Kralovics R. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. [Aug. 2018];N Engl J Med. 2013 369(25):2379–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, Nice FL, Gundem G, Wedge DC, Avezov E, Li J, Kollmann K, Kent DG, Aziz A, Godfrey AL, Hinton J, Martincorena I, Van Loo P, Jones AV, Guglielmelli P, Tarpey P, Harding HP, Fitzpatrick JD, Goudie CT, Ortmann CA, Loughran SJ, Raine K, Jones DR, Butler AP, Teague JW, O’Meara S, McLaren S, Bianchi M, Silber Y, Dimitropoulou D, Bloxham D, Mudie L, Maddison M, Robinson B, Keohane C, Maclean C, Hill K, Orchard K, Tauro S, Du MQ, Greaves M, Bowen D, Huntly BJP, Harrison CN, Cross NCP, Ron D, Vannucchi AM, Papaemmanuil E, Campbell PJ, Green AR. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. [Aug. 2018];N Engl J Med. 2013 369(25):2391–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542. available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1312542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2016 127(20):2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/early/2016/04/11/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, Guglielmelli P, Pacilli A, Pancrazzi A, Pieri L, Fanelli T, Bosi A, Vannucchi AM Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative Investigators. Impact of calreticulin mutations on clinical and hematological phenotype and outcome in essential thrombocythemia. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2014 123(10):1552–1555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538983. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/123/10/1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rumi E, Pietra D, Ferretti V, Klampfl T, Harutyunyan AS, Milosevic JD, Them NC, Berg T, Elena C, Casetti IC, Milanesi C, Sant’antonio E, Bellini M, Fugazza E, Renna MC, Boveri E, Astori C, Pascutto C, Kralovics R, Cazzola M Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative Investigators. JAK2 or CALR mutation status defines subtypes of essential thrombocythemia with substantially different clinical course and outcomes. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2014 123(10):1544–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-539098. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/123/10/1544?sso-checked=true. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Knudson RA, Ketterling R, Hanson CH, Maffioli M, Caramazza D, Passamonti F, Pardanani A. CALR vs JAK2 vs MPL-mutated or triple-negative myelofibrosis: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular comparisons. [Aug. 2018];Leukemia. 2014 28(7):1472–1477. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.3. available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/leu20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tefferi A, Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, Finke C, Mannarelli C, Belachew AA, Pancrazzi A, Wassie EA, Ketterling RP, Hanson CA, Pardanani A, Vannucchi AM. CALR and ASXL1 mutations-based molecular prognostication in primary myelofibrosis: an international study of 570 patients. [Aug. 2018];Leukemia. 2014 28(7):1494–1500. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.57. available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/leu201457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nangalia J, Green TR. The evolving genomic landscape of myeloproliferative neoplasms. [Aug. 2018];Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014 2014(1):287–296. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.287. available at: http://asheducationbook.hematologylibrary.org/content/2014/1/287.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bench AJ, White HE, Foroni L, Godfrey AL, Gerrard G, Akiki S, Awan A, Carter I, Goday-Fernandez A, Langabeer SE, Clench T, Clark J, Evans PA, Grimwade D, Schuh A, McMullin MF, Green AR, Harrison CN, Cross NC British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Molecular diagnosis of the myeloproliferative neoplasms: UK guidelines for the detection of JAK2V617F and other relevant mutations. [Aug. 2018];Br J Haematol. 2013 160(1):25–34. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12075. available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjh.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilbao-Sieyro C, Santana G, Moreno M, Torres L, Santana-Lopez G, Rodriguez-Medina C, Perera M, Bellosillo B, de la Iglesia S, Molero T, Gomez-Casares MT. High resolution melting analysis: a rapid and accurate method to detect CALR mutations. [Aug. 2018];PLoS One. 2014 9(7):e103511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103511. available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0103511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi J, Nicolaou KA, Nicolaidou V, Koumas L, Mitsidou A, Pierides C, Manoloukos M, Barbouti K, Melanthiou F, Prokopiou C, Vassiliou GS, Costeas P. Calreticulin gene exon 9 frameshift mutations in patients with thrombocytosis. [Aug. 2018];Leukemia. 2014 28(5):1152–1154. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.382. available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/leu2013382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones AV, Ward D, Lyon M, Leung W, Callaway A, Chase A, Dent CL, White HE, Drexler HG, Nangalia J, Mattocks C, Cross NC. Evaluation of methods to detect CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. [Aug. 2018];Leuk Res. 2015 39(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.11.019. available at: https://www.lrjournal.com/article/S0145-2126(14)00371-3/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannucchi AM, Rotunno G, Bartalucci N, Raugei G, Carrai V, Balliu M, Mannarelli C, Pacilli A, Calabresi L, Fjerza R, Pieri L, Bosi A, Manfredini R, Guglielmelli P. Calreticulin mutation-specific immunostaining in myeloproliferative neoplasms: pathogenetic insight and diagnostic value. [Aug. 2018];Leukemia. 2014 28(9):1811–1818. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.100. available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/leu2014100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vossen RH, Aten E, Roos A, den Dunnen JT. High-resolution melting analysis (HRMA): more than just sequence variant screening. [Aug. 2018];Hum Mutat. 2009 30(6):860–866. doi: 10.1002/humu.21019. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/111/8/4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergamaschi GM, Primignani M, Barosi G, Fabris FM, Villani L, Reati R, Dell’era A, Mannucci PM. MPL and JAK2 exon 12 mutations in patients with the Budd-Chiari syndrome or extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Blood. 2008;111(8):4418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, Bamford S, Bindal N, Tate J, Cole CG, Ward S, Dawson E, Ponting L, Stefancsik R, Harsha B, Kok CY, Jia M, Jubb H, Sondka Z, Thompson S, De T, Campbell PJ. COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. [Aug. 2018];Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 45(Database issue):D777–D783. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1121. available at: https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/45/D1/D777/2605743?searchresult=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrotra M, Luthra R, Singh RR, Barkoh BA, Galbincea J, Mehta P, Goswami RS, Jabbar KJ, Loghavi S, Medeiros LJ, Verstovsek S, Patel KP. Clinical validation of a multipurpose assay for detection and genotyping of CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. [Aug. 2018];Am J Clin Pathol. 2015 144(5):746–755. doi: 10.1309/AJCP5LA2LDDNQNNC. available at: https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article/144/5/746/1761207?searchresult=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maier CL, Fisher KE, Jones HH, Hill CE, Mann KP, Zhang L. Development and validation of CALR mutation testing for clinical diagnosis. [Aug. 2018];Am J Clin Pathol. 2015 144(5):738–745. doi: 10.1309/AJCPXPA83MVCTSOQ. available at: https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article/144/5/738/1761139?searchresult=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi J, Manoloukos M, Pierides C, Nicolaidou V, Nicolaou K, Kleopa M, Vassiliou G, Costeas P. Calreticulin mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms and new methodology for their detection and monitoring. [Aug. 2018];Ann Hematol. 2015 94(3):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2232-8. available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00277-014-2232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo W, Zhongxin Yu Z. Calreticulin (CALR) mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) [Aug. 2018];Stem Cell Investig. 2015 2:16. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2306-9759.2015.08.01. available at: http://sci.amegroups.com/article/view/7264/8051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rumi E, Pietra D, Pascutto C, Guglielmelli P, Martínez-Trillos A, Casetti I, Colomer D, Pieri L, Pratcorona M, Rotunno G, Sant’Antonio E, Bellini M, Cavalloni C, Mannarelli C, Milanesi C, Boveri E, Ferretti V, Astori C, Rosti V, Cervantes F, Barosi G, Vannucchi AM, Cazzola M Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative Investigators. Clinical effect of driver mutations of JAK2, CALR, or MPL in primary myelofibrosis. [Aug. 2018];Blood. 2014 124(7):1062–1069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-578435. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/124/7/1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabagnols X, Defour JP, Ugo V, Ianotto JC, Mossuz P, Mondet J, Girodon F, Alexandre JH, Mansier O, Viallard JF, Lippert E, Murati A, Mozziconacci MJ, Saussoy P, Vekemans MC, Knoops L, Pasquier F, Ribrag V, Solary E, Plo I, Constantinescu SN, Casadevall N, Vainchenker W, Marzac C, Bluteau O. Differential association of calreticulin type 1 and type 2 mutations with myelofibrosis and essential thrombocytemia: relevance for disease evolution. [Aug. 2018];Leukemia. 2015 29(1):249–252. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.270. available at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/124/21/1823?sso-checked=true. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]