Abstract

The ability to develop and maintain healthy romantic relationships is a key developmental task in young adulthood. The present study investigated how adolescent interpersonal skills (assertiveness, positive engagement) and family processes (family climate, parenting practices) influence the development of young adult romantic relationship functioning. We evaluated cross-lag structural equation models with a sample of 974 early adolescents living in rural and semi-rural communities in Pennsylvania and Iowa, starting in sixth grade (Mean age = 12.4, 62.1% female) and followed into young adulthood (Mean age = 19.5). Findings revealed that adolescents who had experienced a more positive family climate and more competent parenting reported more effective problem-solving skills and less violent behavior in their young adult romantic relationships. Adolescent assertiveness was consistently positively associated with relationship problem-solving skills, and adolescents’ positive engagement with their family was associated with feeling more love in young adult romantic relationships. In addition, family functioning and adolescent interpersonal skills exhibited some reciprocal relations over the adolescent years. In summary, family processes and interpersonal skills are mutually influenced by each other across adolescence, and both have unique predictive implications to specific facets of young adult romantic relationship functioning.

Keywords: family climate, parenting practice, assertiveness, positive engagement, romantic relationship functioning

Introduction

The importance of forming close, meaningful relationships in young adulthood is difficult to overstate. Indeed, the development of romantic relationships is viewed as a central developmental task for young adults (Shulman and Connolly 2013). Young adults who are able to successfully establish and maintain positive intimate relationships tend to be more satisfied with their lives and better adjusted well into later life (e.g., Adamczyk and Segrin 2016; Roisman et al. 2004). Beyond psychological adjustment, the experiences in young adult romantic relationships set the foundation for later relationship success and child caregiving quality after the transition to parenthood (Feinberg 2002; Fincham and Cui 2011). Prior studies often conceptualized romantic relationship quality during young adulthood as a single global construct (e.g., Dush and Amato 2005; Fincham and Cui 2011). However, examining precursors and the development process of particular aspects of young adult romantic relationship functioning, such as relationship related problem-solving skills, love, and conflict, can provide important and more specific information about both relationship-related developmental outcomes and the factors that influence these dimensions. In our conceptualization of romantic relationships, relationship competence refers to the ability to successfully engage and maintain positive romantic relationships, whereas relationship conflict refers, at high levels, to problematic and harmful aspects of relationships (i.e., violence) that place young adults at risk for poor individual or relationship well-being (Davila et al. 2009).

In this study, we focus on two aspects of young adult romantic relationship competence: the development of strong, loving bonds with one’s partner and relationship problem-solving skills. The first domain – developing feelings of love in romantic relationships, such as closeness, belonging, attachment, and deep affection – is an indispensable factor for romantic relationship initiation, engagement, and maintenance (Acevedo and Aron 2009; Dillow et al. 2014). Relationships that are characterized by love, commitment, and mutual engagement are more stable over time, are less likely to end in separation, and promote better psychological and physical well-being (e.g., Le et al. 2010; Strazdins and Broom 2004). The second aspect, effective relationship problem-solving skills include remaining calm, listening to one another, showing respect for others’ opinions, and working toward mutually beneficial resolution during disagreements (Gottman and Notarius 2002; Roisman et al. 2004). Couples that use effective problem-solving strategies tend to preserve relationship quality and satisfaction, even when navigating inevitable problems that arise (Sullivan et al. 2010). Ultimately, couples that can resolve problems amicably are more likely to maintain high levels of relationship satisfaction and are less likely to have disagreements escalate to destructive forms of conflict or experience separation and divorce (e.g., Eğeci and Gençöz 2006; Markman et al. 1993).

In terms of relationship conflict, we focus on physical and psychological violence, which have robust implications for later relationship problems and individual maladjustment (e.g., Campbell 2002; Linder et al. 2002). Young adults who experience violence in their romantic relationships are more likely to enter into subsequent relationships that will be less satisfying and of lower quality (e.g., Bradbury et al. 2000; Linder et al. 2002). Relationship violence places individuals at elevated risk for psychological and physical health problems (Ackard et al. 2007; Coker et al. 2002). Taken together, all three aspects of young adult romantic relationships—problem-solving, love, and violence—hold profound life-course implications. By understanding the developmental precursors in adolescence that promote romantic relationship competence (love, problem-solving skills) and reduce risk for relationship conflict (i.e., violence), prevention developers can better target the key dimensions that promote life-long relationship success.

Individual and Family Precursors to Young Adult Romantic Relationship Functioning

The development of early adult romantic relationships model (Bryant and Conger 2002) proposes that early family relationships and developing interpersonal skills during adolescence serve as distinct pathways to later functioning in young adult romantic relationships. The “enduring family influence” perspective posits that family experiences may have a lasting influence on an individual’s romantic relationships, even when accounting for individual factors or intervening experiences (Raby et al. 2015), such as personality traits, trajectories of hostile-aggressive behavior, or peer relationship experiences (e.g., Donnellan et al. 2005; Fosco et al. 2016). This enduring family influence perspective proposes that the quality of interpersonal interactions within romantic relationships are rooted in one’s earlier family relationship experiences (Fraley and Roisman 2015). Both the development of early adult romantic relationships model and the enduring family influence perspective suggest that family experiences in adolescence may be directly associated with later romantic relationships (even when accounting for the influence of interpersonal skills).

Beyond the enduring effects of the family, the development of early adult romantic relationships model also proposed that adolescents’ interpersonal skills and behaviors that are shaped by early family experiences may serve as pathways to later romantic relationship functioning. However, the mediating role of interpersonal skills as a mechanism for family influence on romantic relationships is not well understood (Carroll et al. 2006). Thus, in the present investigation, we simultaneously tested both enduring family influences and adolescent interpersonal skills as pathways to young adult romantic relationship outcomes.

Enduring family influences on young adult romantic relationships.

The family climate and the quality of parenting experienced during adolescence are two family factors that might exert enduring influences on young adults’ romantic relationship functioning. Family climate is defined in terms of cohesion, organization, and low levels of conflict. A warm and cohesive family climate fosters individuals with better differentiated self, constructive communication patterns, and less hostile-aggressive behaviors, which are closely related to better romantic relationship functioning in young adulthood (Fosco et al. 2016; Holman and Busby 2011). Adolescents in more cohesive and organized families are more likely to form close, intimate, and satisfying significant relationships later in life (e.g., Larson et al. 2001; Masarik et al. 2013). Adolescents who live in families with a more positive climate are thought to develop a more positive interpersonal style which carries over into later romantic relationships (Ackerman et al. 2013; Whitton et al. 2008). On the other hand, family conflict is a risk factor for poorer relationship outcomes, such as less skillful conflict resolution strategies and low involvement in later romantic relationships (Darling et al. 2008; Tyrell et al. 2016). Building on this work, we examined the role of family climate in predicting specific aspects of young adult romantic relationship competence and violence.

Effective parenting practices – including inductive reasoning, and consistent and moderate limit setting– is another family factor that may have long-term implications for young adult romantic relationships (Parade et al. 2012; Surjadi et al. 2013). Parents who use effective practices help promote adolescents’ appropriate and positive interactions with others. For example, adolescents who receive consistent discipline and inductive reasoning are more likely to engage in more positive interactive behaviors with their parents, which is thought to generalize to relationships with their romantic partners and ultimately result in more positive romantic relationships (Donnellan et al. 2005; Tyrell et al. 2016). Similarly, adolescents who benefit from more parental acceptance at home are more likely to engage in positive reciprocal interactions with others (Auslander et al. 2009). Ineffective parenting practices, such as harsh or overprotective parenting, is a risk factor for young adult romantic relationship violence. Such parenting may instill the belief that it is acceptable to use harsh and controlling behavior to deal with conflicts, shape adolescents” use of violence during interpersonal conflicts, and form ambivalence in close relationships (Chang et al. 2003; Surjadi et al. 2013). These maladaptive cognitions and behaviors increase the risk of engaging in violent conflict behaviors with their partners and having less satisfying romantic relationships (Parade et al. 2012; Topham et al. 2005). As a whole, the literature suggests that adolescents who receive more effective parenting will engage in romantic relationships with greater competence and less violence later in life. However, similar to the literature on family climate, it is unclear how effective parenting practices are associated with specific facets of romantic relationship functioning. To fill the gap, the current study aimed to explore the unique predictive effects of family climate and effective parenting practices on three aspects in romantic relationship functioning (i.e. feelings of love, relationship problem-solving skills, and relationship violence).

Interpersonal skill acquisition in adolescence and young adult romantic relationships.

The development of early adult romantic relationships model also proposes that adolescents’ interpersonal skills, influenced by early family experiences, may directly support or undermine success in romantic relationships (Bryant and Conger 2002). Prior work has found that individual interpersonal skill deficits can have toxic effects on romantic relationships. For example, adolescents who hold negative beliefs about relationships, or who have hostile-aggressive tendencies, are at considerably higher risk for relationship violence (e.g., Fosco et al. 2016; Kinsfogel and Grych 2004). However, it is worth noting that the literature to date has been deficit-focused, leaving less known about the role of positive relationship skills in these developmental models (Stanley et al. 2002). The limited empirical evidence in this area suggests that constructive communication and negotiation strategies, such as assertiveness, emotional expression, support, and self-disclosure, facilitate effective problem-solving in relationships and decrease the risk that conflict will result in violence or withdrawal (Hunter 2009; Visvanathan 2009); these skills ultimately promote romantic relationship satisfaction and commitment (Assad et al. 2007; Fischer et al. 2007). However, prior studies have treated positive interpersonal skills as a composite construct, obscuring the unique contribution of various interpersonal skills on romantic relationship quality. Results of work focusing on specific factors would offer important insights for preventive intervention programs, promoting targeting and via more specific logic models, and better evaluation and refinement as well. In the current study, we evaluated two specific positive interpersonal skills—assertiveness and positive engagement with the family—as key individual factors that may set the foundation for subsequent successful romantic relationships.

The degree to which adolescents learn to effectively assert their needs and engage in positive interactions with others may pave the road to young adult relationship competence or violence. Assertiveness refers to the ability to directly and respectfully advocate for one’s needs in relationships, in a non-blaming, non-threatening manner (Lazarus 1973). Thus, assertiveness is an important communication skill for voicing one’s needs in a relationship, especially as couples engage in problem-solving discussions. Assertive adolescents tend to maintain more positive friendships and are better than less assertive adolescents at seeking and gaining social support when they are experiencing difficulties (Eskin 2003; Lazarus 1973). Young adults who are more assertive are more likely to have their needs met in romantic relationships, and have greater relationship satisfaction and stability (Hinnen et al. 2008). Assertiveness skills also are related to a reduced risk of relationship violence such as sexual victimization and coercion, particularly for young women (Simpson Rowe et al. 2012). Overall, assertiveness appears to be a valuable interpersonal skill for promoting effective romantic relationships, eliciting support, and facilitating the successful resolution of relationship conflict.

A second interpersonal skill examined in this study was adolescents’ positive engagement in the family, referring to the adolescents’ tendency to express affection, appreciation, and love toward their parents. Positive engagement in the family sets the foundation for positive interactions in interpersonal scenarios outside of family context (Ackerman et al. 2013), and may serve as a key explanatory link between positive family relationships and young adult romantic relationship competence and violence. Adolescents who are more positive and warm in their interactions with their parents likely elicit more positivity in return, thereby reinforcing adolescent positive engagement. Adolescents in families characterized by more warmth, positive affect, and closeness may adopt positive interpersonal tendencies in other relationships (Carroll et al. 2006; Whitton et al. 2008). This is consistent with findings that adolescent positive engagement with the family predicts young adult romantic relationship quality, above and beyond the effects of family-level and parent-to-adolescent positivity (Ackerman et al. 2013). In turn, engaging in physical and verbal affection with romantic partners is associated with more satisfying intimate relationships in young adulthood (Muise et al. 2014; Pauley et al. 2014). The present study examined unique pathways by which adolescent assertiveness and positive engagement were prospectively linked with young adult romantic relationship love, problem-solving, and violence.

Reciprocal Developmental Relations among Interpersonal Skills and Family Processes

In addition to examining whether family and individual factors predict young adult romantic relationship quality, we also sought to explain the process by which these factors unfold over adolescence. Historically, family socialization of youth attitudes and behaviors has been conceptualized as a unidirectional developmental process: family relationships are thought to shape individual skills, and in turn, individual skills impact young adult romantic relationship functioning (e.g., Bryant and Conger 2002; Whitton et al. 2008). However, it is likely more accurate to consider the interaction between family and individual skills as a transactional process characterized by mutual influence over time (Sameroff 2009). Similarly, family systems theorists advocate for a reciprocal conceptualization of family influence, in which individuals and families are simultaneously influenced by and influencing each other (Cox and Paley 2003). Drawing on transactional and family systems perspectives, this study tested reciprocal relations among family characteristics and individual skills from early to middle adolescence. From this view, one would expect that families providing a more cohesive family climate and effective parenting would promote interpersonal skills such as adolescents’ positive engagement with the family and effective assertiveness skills. Conversely, adolescents’ skills, such as positive engagement and assertiveness, would evoke greater family harmony and effective parenting (e.g., Ackerman et al. 2011; Liu and Guo 2010). Although reciprocal influences are frequently theorized in the family domain, few longitudinal studies explicitly test them (Xia et al. 2016). By conducting an explicit test of transactional effects among family interactions and adolescents’ interpersonal skills, this study can provide new insights into proximal processes that may later affect young adult romantic relationship competence and violence.

The Current Study

The current study was designed to fill gaps in knowledge related to the family and individual factors that underlie specific dimensions of romantic relationship functioning. Guided by the development of early adult romantic relationships model and the transactional models of development, this study tested several hypotheses, nested within two over-arching goals. The first goal of this study was to examine direct precursors of young adult romantic relationship proposed in the development of early adult romantic relationships model. Specifically, this study tested whether family processes (family climate and effective parenting practices) and individual interpersonal skills (assertiveness and positive engagement with family) during adolescence were directly associated with later young adult romantic relationship functioning. The first set of hypotheses was guided by the enduring family influences perspective. Given that positive family climate is thought to cultivate a more positive interpersonal style and less proclivity toward hostility and violence (Ackerman et al. 2013; Fosco et al. 2016), we expected that (H1) more positive family climate would be associated with more positive and loving romantic relationships (Ackerman et al. 2013), better romantic relationship problem-solving skills (Fosco et al. 2016) and less relationship violence in young adulthood (Fosco et al. 2016). Then, building on prior work supporting the positive association between harsh discipline in childhood and violence in romantic relationships (Swinford et al. 2000), we expected that (H2) more effective parenting practices would be associated with reduced risk of young adult relationship violence. However, given limited information about parenting and other aspects of romantic relationships, we conducted these analyses in an exploratory manner to assess links from competent parenting to young adult feelings of love and better problem-solving skills in later romantic relationships.

Adolescent interpersonal factors also were expected to predict aspects of young adult romantic relationship functioning. Drawing on the idea that assertiveness is a critical communication skill underlying relationship conflict resolution, we expected that (H3) adolescents who are more assertive would be better able to engage in effective problem-solving and less likely to use violent tactics in young adult romantic relationships. Regarding adolescent positive engagement with the family, we expected that (H4) adolescent skills in positive engagement with the family would predict later feelings of love and lower risk for violence in young adult romantic relationships (Ackerman et al. 2013; Pauley et al. 2014). As with family predictors, there is limited information about assertiveness as a predictor of later love and about positive family engagement with young adult relationship problem-solving. Thus, these paths were evaluated in an exploratory manner. An added benefit of including these exploratory paths is that it minimizes risk for inflated effects of hypothesized paths that may resulted from omitting paths in the model.

Finally, related to the second goal of this study, we expected to find reciprocal relations among family and individual interpersonal skills over the course of adolescence. Specifically, we hypothesized that (H5) family climate, effective parenting, assertiveness, and positive engagement with the family will exhibit reciprocal relations across three measurement occasions from early to middle adolescence.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The analytic sample in the current study was drawn from the PROSPER project (PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience), a partnership-based delivery system for evidence-based interventions aimed at the reduction of substance misuse and other problem behaviors (Spoth et al. 2004). With the help of three tiers in the existing infrastructure of land grant universities’ Cooperative Extension Systems, PROSPER models serves scientific outreach functions in every state. The original trial was conducted in 28 rural communities and small towns in Iowa and Pennsylvania. Communities randomly assigned to the intervention condition selected and implemented two evidence-based programs (chosen from a menu) designed to reduce adolescent substance use, which were offered to all involved families (see Spoth et al. 2004 for more details about the sample and the PROSPER project). The PROSPER trial was conducted with two successive grade cohorts, each starting when target adolescents were in 6th grade at the start of the trial. The baseline assessment, conducted in participating schools during the fall of 6th grade resulted in 10,849 youth across two cohorts (Cohort 1 began in Spring, 2003 and Cohort 2 began in Spring, 2004) and subsequent in-school assessments were conducted during Spring terms, annually, through high school. A later long-term follow-up project was conducted with a randomly selected subsample of 1988 young adults, oversampling for risk. In this young adult sample, we selected only those young adults who reported they were in romantic relationships at the time of the assessment to serve as the analytic sample. Young adults were asked, “What best describes your current romantic situation?” Those young adults who reported being married (n=0), engaged (n=103), cohabitating with their romantic partner (n=147), or being in a steady relationship with one girlfriend or boyfriend (n=724) were included in the sample; young adults who reported they were not in steady relationships were excluded. This exclusion criterion resulted in a sample of 974 young adults in a stable romantic relationship, and was used as the basis for forming the current analytic sample. Applying this sample selection to the in-school sample, we retained four measurement occasions (including young adult assessment [T4]; mean age = 19.52 [range 18 to 21]): fall of 6th grade (T1, Mean age=12.40 [range 11 to 14], n =974), spring of 7th grade (T2, Mean age=13.89 [range 12.5 to 15.5], n =959), and spring of 9th grade (T3, Mean age=15.90 [range 14.5 to 17.5], n =974). The data collection time between T1 and T2 was 1.5 years, between T2 and T3 was 2 years, and between T3 and T4 was 4 years. Fifty-one percent of the sample were in the intervention group, and 49% were in the control group across all four time points.

The mean duration of young adult romantic relationships was 23.65 months (SD=18.67, ranged from 1 month to 108 months), which is consistent with samples in other studies conducted during the same developmental period (e.g., Cui and Fincham 2010; Morey et al. 2013; Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2010). Some of the young adults in this sample were cohabitating with their partners (21.6%; n=210), but most were not (78.4%; n=764). Ninety-two percent of the participants identified as heterosexual (n=892), 2% as homosexual (n=17), 5% as bi-sexual (n=48), and 1% identified as other (n=17). At T4 (young adult assessment), 73.6% of participants were full-time students (n=717), 7.8% were half-time students (n=76), 17.7% were graduated (n=172), and 0.9% did not provide information (n=9). Regarding employment, 12.7% of participants were working full-time (n=124), 33.7% were working part-time (n=328), 2.5% were in military service (n=24), 50.8% were unemployed (n=495), and 0.3% did not provide information (n=3). At young adult age (T4), the sample’s median monthly income was $570 (in 2010). At T1, 62.1% were female (n=605); 80.1% came from a two-parent family (n=780); 27.9% (n=272) were from low-income families with the criterion that if they got lunch deduction at school, 71.0% (n=691) from normal-income families, and 1.1% (n=11) did not provide information. Youth identified their race as White (91.0%), Hispanic (2.3%), African American (1.5%), Native American (0.9%), Asian (0.4%), Other (3.1%), and information was not provided (0.8%).

Because the sample was based on participation at the young adult measurement occasion, we examined sample attrition at T2 and T3. At T2, 98.5% of the young adult-steady relationship sample participated, and 100% participated at T3. For the entire sample, a Littles’ MCAR test indicated that data were not missing completely at random (χ2(1616) = 2238.117, p < 0.01). Participants who received free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) at school (i.e., the indicator of low family income) were less likely to stay in the study (r = .15 at T2, p < .01). Participants who came from two-parent families were more likely to stay in the study (r = .11 at T2, p < .01). No other variables (including gender, young adult monthly income, and intervention condition) were associated with missing data at subsequent time points. To minimize bias caused by missing data, the structural equation model was estimated using Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation and included FRPL and family structure as covariates in the model (Widaman 2006).

Measures

Family climate.

Adolescents completed 7 items drawn from the Family Environment Scale (Moos and Moos 1981) at T1, T2, and T3. These items included family cohesion (e.g. “Family members really help and support each other”), conflict (e.g. “We fight a lot in our family”), and organization (e.g. “We are generally very neat and orderly”). Items were rated on a 5-point scale, from strongly agree (1), agree (2), neutral or mixed (3), disagree (4), or strongly disagree (5). The scale was scored so that higher values indicated more cohesion, organization, and less conflict in the family. Internal consistencies for the three subscales (cohesion, conflict, and organization) in the prior literature were .79, .75, and .76 respectively (Moos 1990). The internal consistency in our sample was comparable to the original report, with α’s of .75 at T1, .83 at T2, and .82 at T3.

Effective parenting practices.

Adolescents completed 8 items from the General Child Management Scale (Spoth et al. 1998) at T1, T2 and T3, which assessed parents use of inconsistent discipline, harsh discipline, and inductive reasoning. Items were rated on a 5-point scale, from never (1), almost never (2), about half the time (3), almost always (4), or always (5). Sample items include, “When my parents discipline me, the kind of discipline I get depends on their mood (inconsistent discipline)”, “When I do something wrong, my parents lose their temper and yell at me (harsh discipline)”, and “My parents give me reasons for their decision (inductive reasoning)”. Items were averaged to create a single score so that higher values reflected more effective parenting, defined as higher in consistent discipline, inductive reasoning, and lower in harsh discipline. The internal consistency was not reported in the original scale (Spoth et al. 1998). In our sample, the reliability was acceptable (α’s: .71 at T1, .79 at T2, and .78 at T3).

Adolescent assertiveness.

Adolescents completed 5 items from Gambrill and Richey Assertion Inventory at T1, T2, and T3 (Gambrill and Richey 1975). Scale reduction was conducted by primary investigators of the PROSPER trial, who used a combination of face validity and reliability analysis to identify a set of items that were both developmentally appropriate and empirically valid. Following the stem “How likely would you be to…” items included: “Express an opinion even though others may disagree with you”, “Ask a teacher to explain something you don’t understand”, “Say no when someone asks you to do something that you don’t want to do”, “Compliment your friends”, and “Ask for directions if you don’t know where you are.” Adolescents rated on a 5-point scale from definitely would not (1), probably would not (2), not sure (3), probably would (4), or definitely would (5). Higher scores reflected more assertive behavior. Reliability of the original scale was not reported (Gambrill and Richey 1975). In the current study the reliability was adequate: .68 at T1, .74 at T2, and .79 at T3.

Adolescent positive engagement.

Adolescents completed three items adapted from the Affective Quality of the Relationship scale at T1, T2, and T3 (Spoth et al. 1998). These items were completed separately for their positive behavior with their mothers and with their fathers. Items included (affective quality to mother as an example), “Let her know you really care about her”, “Act loving and affectionate toward her”, and “Let her know that you appreciate her, her ideas, or the things she does”. Items were rated from on a 5-point scale from never or almost never (1), not very often (2), about half the time (3), often (4), or always or almost always (5). The six items from the two scales were summed together, so that high values reflected higher levels of adolescents’ positive engagement with their parents. The internal consistency was not reported in the original scale (Spoth et al. 1998); however, the reliability in this sample was good( .93 at T1, .94 at T2, and .94 at T3).

Romantic relationship love.

At the young adult assessment, young adults completed 5 items from the Love subscale, taken from the Love and Conflict Scale (Braiker and Kelley 1979) to capture the degree to which they felt connected, trusting, and loving toward their partner. Sample items include: “To what extent do you have a sense of ‘belonging’ with your partner?” and “To what extent do you love your partner at this stage?” Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5). The scale was computed so that higher scores reflect more love in their romantic relationships. The reliability was not reported in the original questionnaire (Braiker and Kelley 1979). In this sample, the reliability was acceptable (α=.81).

Romantic relationship problem solving skills.

Young adults responded to 8 items to capture their strategies for resolving disagreements or problems in their romantic relationships. Seven items were taken from the Cooperative Problem Solving Measure (Assad et al. 2007) and one additional item “How often do you have good ideas about how to solve the problem” to assess participants’ romantic problem-solving skills. Items were listed after the stem: “When you and your partner have a problem to solve, how often do you…”, and included: “Listen to your partner’s ideas about how to solve the problem”, “Criticize your partner or his/her ideas for solving the problem [reverse coded]”, and “Show a real interest in helping to solve the problem”. Young adults rated items using a 6-point scale from almost never (1), not too often (2), about half the time (3), fairly often (4), almost always (5), or always (6). The scale was scored such that higher values reflected better romantic problem-solving skills in communication and interaction processes. The original scale had good internal consistency (α’s: .84 to .87). In this sample, the reliability was acceptable (α=.79).

Romantic relationship violence.

Romantic relationship violence was assessed by self-reports of verbal and physical aggression in relationships at young adult assessment, using 11 items measuring psychological and physical violence from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus 1979). Items were rated on a 6-point scale from zero times (0), one time (1), two times (2), three to five times (3), six to ten times (4), eleven to twenty times (5), to more than twenty times (6). Example items include: In the past year “I insulted or swore at my partner”, “I threw something at my partner”, and “I twisted my partner’s arm or hair”. The scale was computed so that higher values indicated more frequent use of aggression in romantic relationships. The original report for the CTS internal consistency ranged from .70 to .88. In this sample, the internal consistency was good (α=.85).

Covariates.

To account for the possible impact of participants’ personal, social, and family-of-origin characteristics on the paths among family processes, interpersonal skills, and romantic relationship outcomes in the model, the following seven covariates were included in our models (e.g., Connolly and Johnson 1996; Diamond 2003; Stafford and Canary 1991; Stanley et al. 2011). At T1, Free and Reduce-Priced Lunch (FRPL) was used as a proxy for family income and coded so that higher values reflect lower risk; (0) indicated receiving FRPL, (1) not receiving FRPL. Family-of-origin structure was scored as: (0) other, (1) from two-parent family (including intact and step families). Participants’ gender was coded as (1) male, (2) female. Sexual orientation was coded as (1) heterosexual, (0) other. We also included three covariates at T4: ages at young adult assessment, relationship duration, and if they were (1) cohabitating or (0) not.

Results

Analysis Plan

The structural equation models were estimated using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 2013). Family climate and effective parenting practices were evaluated in separate model because of issues with multicollinearity (rs ranged from .58 to .66 across T1 – T3). Thus, two cross-lagged models were used to test hypotheses related to transactional effects between family factors and interpersonal factors across T1 – T3. An advantage of cross-lag models is the ability to avoid bias incurred from assumptions about the direction of effects (Selig and Little 2012). All three dimensions of young adult romantic relationship functioning were simultaneously regressed on T3 family functioning (family climate in Model 1, effective parenting in Model 2), assertiveness, and positive engagement with the family, to evaluate the unique predictive effects of family variables and interpersonal skills. All endogenous variables were regressed on covariates: family income, family structure, and adolescent gender on T1. In addition, young adult relationship outcomes also were regressed on several covariates measured at the same time point: relationship duration, cohabitation status, sexual orientation, and their age at YA assessment. Model fit was considered adequate when the comparative fit index (CFI) value was greater than .95, the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) value was greater than .90, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value was less than 0.08, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value was less than .08 (Hu and Bentler 1999). If the model fit is acceptable, post-hoc multiple group invariance tests between intervention or control conditions and between males and females were conducted to ensure there were no differences in the developmental processes for youths between intervention or control groups and between males and females. These comparisons were accomplished by comparing multiple group model fits when parameters were freely estimated across groups to a model with parameters constrained to be equal across groups. The overall model was determined to fit well across groups if the change in CFI (ΔCFI) was less than or equal to .01. Simulation data indicates that ΔCFI is preferred over Chi Square comparisons for large samples (Cheung and Rensvold 2002).

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1. Across T1–T3, family climate, effective parenting, adolescent assertiveness, and adolescent positive engagement with the family all demonstrated stability over time and were correlated with each other in the expected directions. In addition, most adolescent variables were correlated with young adult romantic relationship outcomes as expected. Thus, we proceeded to estimate structural equation models. In autoregressive cross-lag models, cross-lagged paths often generate very small effect sizes; it is meaningful to interpret these significant small effects above beyond much larger stability effects (Adachi and Willoughby 2015). Significant paths and non-significant paths were presented in solid and dashed lines, respectively, with standardized coefficients in figures.

Table 1.

Correations, Means, and Standard Deviations

| Family Climate | Effective Parenting | Assertiveness | Pos. Engagement | YA Rom. Rels. | Control Variables | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 1. Climate1 | -- | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Climate2 | .57 | -- | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Climate3 | .45 | .64 | -- | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Parent1 | .58 | .41 | .34 | -- | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Parent2 | .48 | .66 | .47 | .52 | -- | |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Parent3 | .36 | .49 | .63 | .44 | .60 | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Assertive1 | .33 | .23 | .15 | .29 | .29 | .14 | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Assertive2 | .29 | .37 | .25 | .30 | .41 | .26 | .38 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 9. Assertive3 | .19 | .20 | .27 | .24 | .21 | .26 | .26 | .38 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 10. Pos.Eng1 | .47 | .37 | .28 | .40 | .30 | .25 | .22 | .23 | .13 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 11. Pos.Eng2 | .44 | .58 | .43 | .38 | .55 | .42 | .21 | .37 | .20 | .59 | -- | |||||||||||

| 12. Pos.Eng3 | .30 | .40 | .52 | .26 | .40 | .53 | .12 | .20 | .31 | .40 | .60 | -- | ||||||||||

| 13. Love | .09 | .13 | .13 | .08 | .10 | .07 | .07 | .06 | .09 | .08 | .16 | .14 | -- | |||||||||

| 14. Prob-Solv | .17 | .18 | .24 | .19 | .16 | .22 | .08 | .11 | .16 | .09 | .13 | .15 | .35 | -- | ||||||||

| 15. Violence | −.16 | −.16 | −.19 | −.15 | −.16 | −.20 | −.06 | .00 | −.01 | −.05 | −.07 | −.14 | −.07 | −.39 | -- | |||||||

| 16. F.Inc | .17 | .13 | .17 | .16 | .12 | .14 | .09 | .03 | .06 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | .01 | .05 | −.10 | -- | ||||||

| 17. F.Str | .08 | .10 | .11 | .12 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .02 | −.04 | .01 | .00 | .02 | .02 | .03 | −.12 | .28 | -- | |||||

| 18. Gender | .01 | .00 | −.10 | −.02 | −.01 | −.07 | .15 | .12 | .18 | .09 | .08 | −.02 | .09 | .01 | .17 | −.04 | −.05 | -- | ||||

| 19. Duration | .01 | .01 | .03 | .04 | −.02 | −.01 | .00 | −.05 | −.05 | .06 | −.03 | −.02 | .07 | −.14 | .00 | .04 | .00 | −.01 | -- | |||

| 20. Sex.Ort | .04 | .06 | .10 | .05 | .07 | .03 | .01 | .05 | −.03 | .02 | .05 | .00 | .04 | −.01 | −.03 | .09 | .05 | −.08 | .02 | -- | ||

| 21. Cohabit | −.15 | −.18 | −.17 | −.16 | −.17 | −.15 | −.02 | −.14 | −.04 | −.08 | −.18 | −.10 | .07 | −.05 | .13 | −.15 | −.15 | .12 | .14 | −.07 | -- | |

| 22. AgeT4 | −.11 | −.07 | −.02 | −.04 | −.07 | −.03 | −.04 | −.07 | .00 | −.09 | −.04 | −.03 | −.09 | −.06 | .02 | −.03 | −.01 | −.09 | .02 | .01 | .05 | -- |

| M | 3.59 | 3.51 | 3.35 | 3.68 | 3.63 | 3.42 | 4.24 | 4.23 | 4.28 | 4.27 | 3.89 | 3.47 | 4.70 | 5.65 | .49 | .72 | .80 | 1.62 | 23.65 | .92 | .22 | 19.52 |

| SD | .74 | .80 | .76 | .76 | .82 | .77 | .63 | .68 | .67 | .91 | 1.11 | 1.17 | .49 | .77 | .64 | .45 | .40 | .49 | 18.67 | .27 | .41 | .52 |

Note. Due to space limitations, statistically significant correlations are bolded (p < .05).

Abbreviations: Climate = family climate, Parent = parenting practice, Assertive = Assertiveness, Pos.Eng = positive engagement, Love = romantic relationship love, Prob-Solv = romantic relationship problem-solving skills, Violence = romantic relationship violence, F.Inc = family income, F.Str = family structure (0=two-parent family, 1=other), Gender = Gender (1=male, 2=female), Duration = relationship duration, Sex.Ort = sexual orientation, AgeT4 = Participants’ ages in Young Adulthood. Numbers after abbreviations represent the measurement occasion, T1, T2, and T3.

Model 1: Examining Family Climate, Interpersonal Skills, and Romantic Relationship Functioning

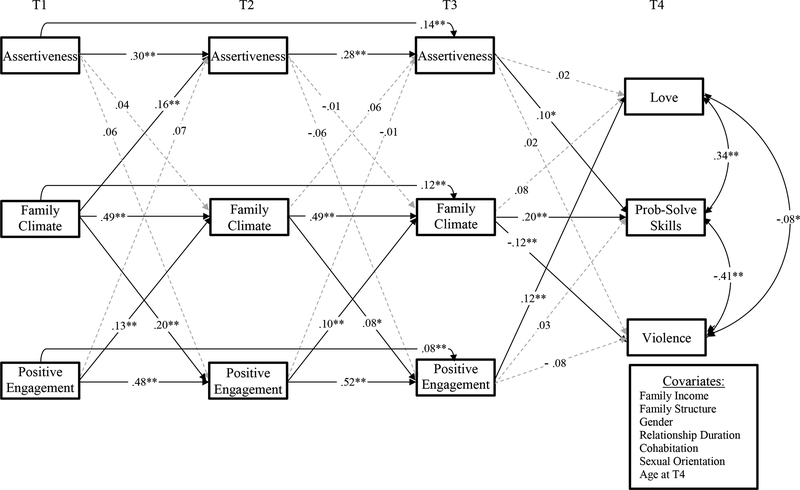

Model 1 was a cross-lagged model with family climate and two interpersonal skills across T1 to T3, and three romantic relationship outcomes at T4 were regressed on the three variables at T3 (see Figure 1). The model fit for Model 1 was acceptable, where χ2(69) = 161.622, p < 0.01; CFI = .964; TLI = .935; RMSEA = .038 (90%: .030–.046); SRMR = .039.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal Cross-Lag Model of Family Climate and Interpersonal Skills Predicting Young Adult Romantic Relationship Functioning

Model fit: χ2(69) = 161.622, p < 0.01; CFI = .964; TLI = .935; RMSEA = .038 (90%: .030–.046); SRMR = .039. ** p<.01, *p<.05 Standardized path coefficients are presented in this model. Covariances among variables within time points (T1, T2, T3, T4) were estimated, but not depicted for clarity of presentation. Covariances in this model: family climate and assertiveness .32 (T1), .26 (T2) and .23 (T3); family climate and positive engagement .47 (T1), .46 (T2), and .38 (T3); assertiveness and positive engagement .21 (T1), .27 (T2), and .29 (T3).

There were several statistically significant paths between covariates and endogenous variables in Model 1. Compared with males, females reported a less positive family climate (T3, β = - .12), less positive family engagement in middle adolescence (T3, β = - .08), and higher assertiveness in early to middle adolescence (T2, β = .08 and T3, β = .12). In addition, females reported more feelings of love (T4, β = .10) and perpetrating more violence (T4, β = .13) than males in young adult romantic relationships. Two-parent household status was associated with lower assertiveness in middle adolescence (T3, β = - .07). Adolescents from higher-income families reported a more positive family climate than adolescents from low-income families (T3, β = .07). With respect to young adult covariates, young adults who were cohabitating with their partners reported higher levels of love (β = .09), but reported more relationship violence as well (β = .10). Romantic relationships of longer duration were associated with more feelings of love (β = .09) and less relationship problem-solving skills (β = - .13). Young adults’ age at the young adult assessment was negatively correlated with their feelings of love (β = - .09). The rest of the paths between covariates and endogenous variables were not significant.

Predicting young adult romantic relationship functioning.

The results presented in Figure 1 provide support for both enduring family influence and adolescent interpersonal skill perspectives. In terms of enduring family effects (H1 and H2), the findings in Model 1 indicated that family climate during adolescence at T3 was directly associated with better relationship problem-solving skills (β = .20) and less risk for relationship violence (β = - .12) at the young adult assessment. However, family climate was not associated with young adults’ feelings of love in romantic relationships. The results also supported hypotheses regarding adolescent interpersonal skills as predictors of young adult romantic relationship outcomes. Specifically, adolescent assertiveness at T3 was associated with more effective problem-solving strategies in young adult romantic relationships (β = .10). However, assertiveness was not associated with the other two aspects of romantic relationship functioning. On the other hand, adolescent positive engagement with their family at T3 was associated with stronger feelings of love in romantic relationships (β = .12), but it was not associated with violence or problem-solving skills.

Reciprocal relations among family processes and interpersonal skills.

We then examined the cross-lag paths from T1 to T3 regarding the hypothesized reciprocal influences between family processes and interpersonal skills (H5). In Model 1, family climate at T1 was associated with increases in adolescents’ assertiveness (β = .16) and increases in adolescents’ positive engagement with the family (β = .20) at T2. From T2 to T3, family climate was associated with increases in adolescents’ positive engagement with the family (β = .08) but did not predict assertiveness. There also were reverse effects in which adolescent interpersonal skills predicted change in family functioning over time as well. Adolescent positive engagement at T1 was associated with increases in family climate at T2 (β = .13); this effect was replicated from T2 to T3 as well (β = .10). However, associations between assertiveness and family climate were not significant from T1 to T2 or from T2 to T3.

Post-hoc multiple group invariance tests evaluated whether the model held equally well for youth in the intervention and control groups, and between males and females. Comparison of the constrained and freely estimated models indicated no meaningful differences across groups (ΔCFI = .008 and .002, respectively). Thus, the overall model was retained.

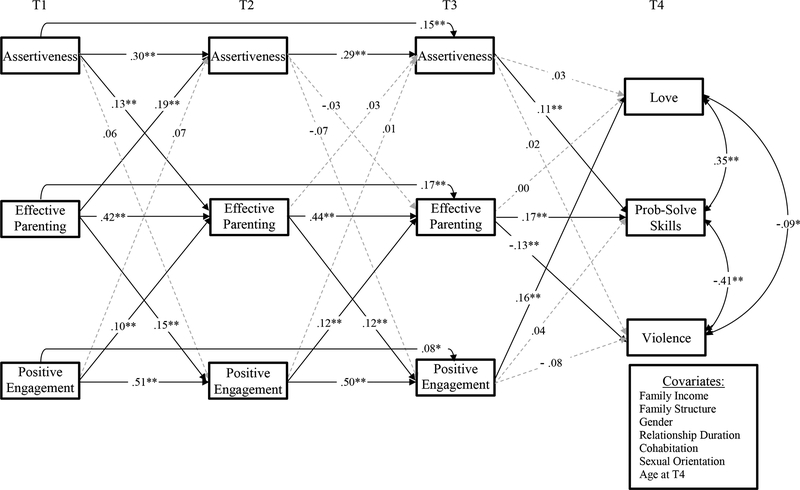

Model 2: Examining Effective Parenting, Interpersonal Skills, and Romantic Relationship Functioning

The cross-lagged model examined effective parenting practices and both adolescent interpersonal skills across T1 to T3. In turn, three young adult romantic relationship outcome variables at T4 were regressed on the three variables at T3 (see Figure 2). The model fit for Model 2 was acceptable, where χ2(69) = 168.864, p < 0.01; CFI = .960; TLI = .927; RMSEA = .039 (90%: .032–.047); SRMR = .039.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal Cross-Lag Model of Effective Parenting and Interpersonal Skills Predicting Young AdultRomantic Relationship Functioning

Model fit: χ2(69) = 168.864, p < 0.01; CFI = .960; TLI = .927; RMSEA = .039 (90%: .032–.047); SRMR = .039. ** p<.01, *p<.05 Standardized path coefficients are presented in this model. Covariances among variables within time points (T1, T2, T3, T4) were estimated, but not depicted for clarity of presentation. Covariances in this model: parenting and assertiveness .28 (T1), .29 (T2) and .21 (T3); effective parenting and positive engagement .40 (T1), .47 (T2), and .40 (T3); assertiveness and positive engagement .22 (T1), .27 (T2), and .28 (T3).

Similar to Model 1, several significant associations emerged between covariates and endogenous variables. Specifically, females reported experiencing less effective parenting in middle adolescence (T3, β = - .06), less positive engagement in middle adolescence (T3, β = - .08), and reported being more assertive in early to middle adolescence (T2, β = .08 and T3, β = .12). In addition, females reported more feelings of love (T4, β = .09) and perpetrating more violence (T4, β = .13) in young adult romantic relationships. Two-parent household status was associated with lower assertiveness in middle adolescence (T3, β = - .07). With respect to young adult covariates, young adults who were cohabitating with their partners reported higher levels of love (β = .08) but more relationship violence (β = .10) as well. Romantic relationship duration was correlated with more feelings of love (β = .09) and less relationship problem-solving skills (β = - .12). Young adults’ age at the young adult assessment was negatively correlated with their feelings of love (β = - .09). The rest of the paths between covariates and endogenous variables were not significant in Model 2.

Predicting young adult romantic relationship functioning.

Results from Model 2 indicated that effective parenting practices at T3 was associated with better relationship problem-solving skills (β = .17) and less risk for relationship violence (β = - .13) at T4. However, effective parenting was not significantly associated with young adult feelings of love in romantic relationships. Similar to the previous findings, adolescent interpersonal skills also were associated with young adult relationship quality. Adolescent assertiveness at T3 was associated with more effective problem-solving strategies (β = .11), but was not associated with violence or love in young adult romantic relationships. On the other hand, adolescent positive engagement with their family at T3 was associated with stronger feelings of love (β = .16), but it was not associated with violence or problem-solving skills in romantic relationships.

Reciprocal relations among family processes and interpersonal skills.

We then examined the hypothesis of transactional relations among family processes and interpersonal skills in Model 2. Specifically, effective parenting at T1 was associated with increases in assertiveness (β = .19) and positive engagement (β = .15) at T2. Effective parenting at T2 predicted increases in positive engagement in the family (β = .12), but did not predict assertiveness at T3. In the reverse direction, adolescent positive engagement at T1 also predicted increases in effective parenting at T2 (β = .10); this effect was replicated from T2 to T3 as well (β = .12). Moreover, assertiveness at T1 was associated with increases in effective parenting practices at T2 (β = .13); however, this association was not significant at the later period (T2 to T3). In both models, family factors were more robust predictors of interpersonal skills at earlier time points.

Post-hoc multiple group invariance tests were also conducted to evaluate whether the model held equally well for youth in the intervention and control groups, and between males and females. Comparison of the constrained and freely estimated models indicated no meaningful differences across groups (ΔCFI = .000 and .010, respectively), similar to Model 1. Thus, the overall model was retained.

Discussion

The degree to which young adults engage successfully in their romantic relationships, by forming loving and connected bonds, using effective problem-solving strategies, and avoiding problematic or violent conflicts, has important life course implications (e.g., Roisman et al. 2004; Williams and Umberson 2004). Informed by the development of early adult romantic relationships model (Bryant and Conger 2002), the current study sought to identify individual interpersonal skills and family characteristics during adolescence that serve as unique pathways to three aspects of young adult romantic relationship functioning (i.e., feelings of love, relationship problem-solving skills, and [a lack of] relationship violence). In addition, this study evaluated a transactional developmental hypothesis in which adolescent family experiences (overall family climate and parenting practices) and interpersonal skills (positive engagement and assertiveness) were expected to exhibit reciprocal relations with one another across adolescence.

The Role of Family Climate and Effective Parenting Practices for Young Adult Romantic Relationships

This study evaluated the hypothesis that family functioning during adolescence may be directly associated with young adult romantic relationship quality, even when accounting for individual interpersonal skills, is consistent with premises set forth from an enduring family influences perspective (Fraley and Rosiman 2015) and the development of early adult romantic relationships model (Bryant and Conger 2002). Using prospective longitudinal methods, our findings provide support for these hypotheses, over a 3–6-year period. Consistent with our first hypothesis, young adults from families characterized by cohesion, organization, and low levels of conflict reported that they used more constructive problem-solving strategies and engaged in less violence in their romantic relationships. Our findings are consistent with prior work documenting a link between a positive family climate and more effective conflict resolution in adolescents’ dating relationships (Darling et al. 2008; Lichter and McCloskey 2004) and extend the developmental timeframe for such work into young adulthood. Family cohesion, organization, and low levels of conflict during adolescence may model and actively involve adolescents in the process of navigating challenges in personal relationships and help them develop problem-solving skills that can later be generalized to romantic relationships. Thus, family relationships may help youth develop problem-solving skills to prevent conflict from escalating into destructive forms (Feldman and Ridley 2000), and these skills may generalize to future young adult romantic relationships (Johnson and Ferraro 2000). Interestingly, the results from the current study did not find a significant association between family climate and feelings of love in later romantic relationships, despite prior work supporting this link (Fosco et al. 2016). Instead, it may be that family climate most directly impacts interpersonal skills (e.g., interpersonal problem-solving), and it may be the case that the influence of family climate on young adults’ ability to develop intimacy is more indirect (through promoting positive interpersonal skills).

We also examined the role of positive parenting practices—i.e., consistent, appropriate discipline and inductive reasoning—as a direct predictor of specific aspects of young adult romantic relationship outcomes. As hypothesized, adolescents who benefitted from more effective parenting practices were less likely to use violence in later romantic relationships. Effective parenting practices significantly predicted better relationship problem-solving skills but were not related to feelings of love in those relationships. These findings are consistent with other work suggesting that consistent parenting discipline and inductive reasoning may coach adolescents to identify and voice their needs in a respectful way within the family (Liu and Guo 2010). These skills facilitate relationship problem-solving processes and our results indicate they may generalize to consequently improve problem solving and reduce violence in later romantic relationships. Overall, our findings echo prior work documenting longitudinal effects of warm-nurturant parenting during adolescence on global assessment of young adult romantic relationship quality (e.g, Donnellan et al. 2005; Leadbeater et al. 2008), and shed new light on the implications of parenting for specific facets of romantic relationship quality (i.e., problem-solving and violence). Effective parenting practices, such as consistency and inductive reasoning, help manage adolescents’ misbehavior without using power-assertive techniques, and may socialize adolescents to adopt a similar constructive approach in their romantic relationships, while preventing the escalation of aggression (Dishion and Patterson 2006; Swinford et al. 2000). Our findings converge around the notion that these family experiences have long-lasting effects on the quality of interpersonal interactions in young adults’ romantic relationships, underscoring the potential value of promoting family climate and effective parenting practices during the adolescent years.

Adolescent Interpersonal Skills: Implications for Young Adult Romantic Relationships

Our findings also showcase the importance of adolescents’ interpersonal skills (fostered by early family experience) for young adult romantic relationship quality, as articulated in the development of early adult romantic relationships model (Bryant and Conger 2002). Building on prior work that has focused primarily on interpersonal deficits (e.g., personality traits, hostile-aggressive behavior) as risk factors for romantic relationship functioning, this study provides insights into the value of assertiveness and positive engagement with the family as key positive interpersonal skills that serve as precursors to positive young adult romantic relationships. Adolescents who were more assertive were better able to engage in effective relationship problem-solving strategies, across both of our structural equation models; however, assertiveness was not associated with relationship violence or love. Thus, our findings suggest that assertiveness may have specific implications for problem-solving processes in romantic relationships. Individuals who are adept at advocating for their needs also tend to be better able to stay engaged in problem-solving processes and address issues as they arise, rather than waiting until several problems have accumulated and addressing them all at once (Knee et al. 2008). Thus, assertiveness is thought to foster better problem-solving skills in later relationships (Eskin 2003) and may be an essential relationship skill (Wolfe et al. 2003).

It was particularly surprising that assertiveness was not associated with relationship violence in this study. These findings run contrary to other work that has demonstrated assertiveness training to reduce risk for sexual coercion and dating violence (e.g., Simpson Rowe et al. 2012; Wolfe et al. 2003). A likely explanation for this discrepancy is the operationalization of relationship violence. Our study examined whether assertiveness might reduce risk for the perpetration of psychological or physical violence; whereas other work has documented an association focused on victimization. It is possible that assertiveness skills impact effective problem-solving in young adult relationships as well as reduce risk for victimization but do not reduce risk for perpetrating violence. Future work is needed to examine the relationship between assertiveness and both victimization and perpetration outcomes to clarify this potential distinction.

Our findings underscore adolescent positive engagement in the family as a specific predictor for feelings of love in young adult romantic relationships. Although other work has documented a link between attachment style and romantic love (Mikulincer and Goodman 2006), the current study highlighted the importance of adolescents’ behavior engagement with their parents (e.g., expressing affection) —a family process that is often overlooked —to the feelings of love in their young adult romantic relationships. These findings parallel those reported by Fosco and colleagues (2014), linking adolescents’ hostile behaviors toward their parents and later aggression problems in other contexts. Similar to those findings, adolescents’ positive engagement with their parents was a key proximal pathway to forming loving romantic relationships in young adulthood. It is likely that adolescent behavior is part of a broader cycle in which positive engagement with parents elicits more positive parenting practices, which in turn further fortifies adolescents’ tendency to express affection, love, and care for their family members (Ackerman et al. 2011). This positive feedback cycle, discussed later, may establish an interactional “set” that generalizes to romantic relationships in young adulthood (Ackerman et al. 2013). The degree of specificity in the effects of adolescent’s positive engagement on different romantic relationship outcomes is worth noticing. Based on prior work, we expected that positive family engagement would also be linked to less in relationship violence (e.g., Parade et al. 2012; Simons et al. 2008). However, we did not find support for this association. It is possible that the study design, drawing on multiple aspects of family functioning, interpersonal skills, and the multivariate treatment of young adult relationship quality sheds new light on the specific role of positive interpersonal skills for relationship quality. Future research and replication is needed to further clarify the inconsistent findings.

Reciprocal Relations among Family Processes and Interpersonal Skills

Guided by family systems and transactional views of development, this study evaluated the hypothesis that family factors and adolescent interpersonal skill development unfold in a reciprocal process over time (Cox and Paley 2003; Sameroff 2009). Both family climate (Model1) and effective parenting practices (Model 2) exhibited reciprocal associations with adolescent positive engagement in the family. Specifically, positive family climate and effective parenting practices were associated with increases in adolescent positive engagement with the family; just as adolescent positive engagement in the family was associated with improved family climate and parenting effectiveness over time. The reciprocal relations were found across all waves tested in this study, suggesting a robust finding. Overall, these findings demonstrate the transactional processes between family factors and adolescent positive engagement: positive family relationships and effective parenting practices promote adolescent positive engagement with the family; likewise, adolescents’ positive engagement evokes greater harmony in the family climate and more competent parenting behaviors (Leidy et al. 2010). These findings are consistent with a mutually reinforcing process of reciprocal positivity among individuals and relationships over time.

The reciprocal linkages between assertiveness and parenting were inconsistent across time and measures of parenting. We found a transactional relationship between assertiveness and effective parenting practices during early adolescence, but not between assertiveness and family climate. Our results indicated that effective parenting was related to increases in adolescent assertiveness in early adolescence (T1 to T2), and adolescent assertiveness predicted more effective parenting during this time. However, in the model examining family climate, the pattern of results differed, suggesting a unidirectional pattern in which family climate predicted increases in adolescent assertiveness during early adolescence, but assertiveness did not predict family climate. Moreover, no associations between family factors and assertiveness were significant during middle adolescence (T2 to T3). Taken together, these findings suggest a developmental timing in which family influence on assertiveness is stronger early in adolescence than in middle adolescence. Assertiveness may be a developmentally important skill during early adolescence. Since adolescents begin seeking new levels of autonomy and independence from the family, there is a potentially new expansion of assertiveness during early adolescence. By middle adolescence, the changes in parental authority and adolescent autonomy may stabilize, and former may then exert diminished influence on adolescents’ assertive skills (McLean et al. 2010; Wigfield et al. 2006). It may also be that peer relationship influence surpasses family influence on adolescents’ assertive behavior during middle adolescence. It would be valuable for future studies to investigate other influences on middle adolescents’ assertiveness skills.

Although our study is consistent with prior work documenting the impact of family experiences in shaping adolescent interpersonal skills, our findings also underscore adolescent agency in shaping family functioning and parenting practices. In particular, adolescent assertiveness was associated with increases in effective parenting during early adolescence, while positive family engagement was associated with increased effective parenting in both early and middle adolescence. Similar to a social interactional learning perspective, these findings may reflect a pattern of positive reciprocity between parenting practices and adolescent behavior in the family. Adolescents who express their needs clearly and respectfully and who show affection to their parents, may elicit more responsive and involved parenting. Such a positive reciprocal process may reflect positive reinforcement of effective self-assertion in adolescents (e.g., Beyers and Goossens 2008; Robin and Foster 2002). Likewise, with regard to shaping the broader family climate, adolescent positive engagement and family climate also exhibited a transactional relationship. Indeed, as Ackerman and his colleagues (2011) report, through their individual contribution of positive interactions with the family, adolescents may be empowered to shift the overall family climate in a positive way by promoting cohesion, organization, and reducing conflict. These finding concur with other work emphasizing adolescent positive interactions with parents is an important family process to consider in conceptualizations of the family (Crouter and Booth 2003) and for family-based interventions (Van Ryzin et al. 2016).

Limitations and Future Direction

This study should be evaluated within the context of its limitations. First, the sample generalizability was limited to rural and semi-rural, White families. In addition, youth in this sample were disproportionally female. Replication with more diverse and gender-balanced samples is important to better understand whether these findings apply equally well to other races, cultures, and contexts (e.g., urban or suburban families). Second, this study relied on mono-informant data, and is vulnerable to self-report bias. Replications of these findings with multi-informant, multi-method data would be valuable. Third, this study was limited to adolescent and young adult developmental periods. Future work that can extend the developmental range further into early childhood would provide a more complete picture of the developmental course of young adult romantic relationships. Fourth, it would be valuable to examine other relationship outcomes—such as whether or not young adults are in a committed relationship, experience sexual violence, or the extent of their feelings of commitment to their partner—in this developmental model. Fifth, future work can involve in variables on peer relationships in high school to have a panoramic view from multiple interpersonal contexts and examine how they work in concert with each other.

Conclusion

Using a sample of young adults who were in steady romantic relationships, this study evaluated premises set forth by the development of early adult romantic relationships model and a transactional model of development in understanding the process by which family and individual factors shape young adult romantic relationships. By examining family-level climate, parenting behaviors, adolescent assertiveness, and adolescent positive engagement with the family, a nuanced view of the pathways that lead to competence and violence in young adult romantic relationships emerged. Adolescents in families with a more positive family climate and effective parenting practices reported more effective problem-solving skills and lower risk for relationship violence in young adult relationships. In addition, adolescents who were more assertive and positively engaged with their families reported better problem-solving and more intimacy, love, and connection in their young adult relationships. These findings generally supported propositions of the development of early adult romantic relationships model (Bryant and Conger 2002), and expand on it by examining the transactional process by which family climate, parenting practices, adolescent positive engagement with the family, and adolescent assertiveness unfold over time. Our analyses provide compelling support for a pattern of reciprocal influence over time that ultimately impacts later romantic relationship quality.

The current findings may be applied to work seeking to understand the role of family-based interventions in promoting adolescents’ ability to form rewarding, healthy, and lasting romantic relationships—an important indicator of successfully transitioning into young adult roles. Specifically, our findings suggest that there are multiple opportunities and targets for intervention including family relationships, effective parenting, and adolescent interpersonal skills; each offer added value to fostering later relationship functioning. Second, our findings on the reciprocal influence between family climate, parenting, and adolescent positive engagement in the family suggest that it would be valuable to involve all family members in the same change process to maximize intervention effectiveness. Finally, our findings indicate that these interventions may be most effective during the early adolescent years, given the apparent decline in the influence of family factors on adolescents’ interpersonal skills by middle adolescence.

References

- Acevedo BP, & Aron A (2009). Does a long-term relationship kill romantic love? Review of General Psychology, 13, 59–65. 10.1037/a0014226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2007). Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. The Journal of Pediatrics, 151, 476–481. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman RA, Kashy DA, Donnellan MB, & Conger RD (2011). Positive engagement behaviors in observed family interactions: A social relations perspective. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 719–730. 10.1037/a0025288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman RA, Kashy DA, Donnellan MB, Neppl T, Lorenz FO, & Conger RD (2013). The interpersonal legacy of a positive family climate in adolescence. Psychological Science, 24, 243–250. 10.1177/0956797612447818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi P, & Willoughby T (2015). Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 116–128. 10.1080/17405629.2014.963549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk K, & Segrin C (2016). The mediating role of romantic desolation and dating anxiety in the association between interpersonal competence and life satisfaction among polish young adults. Journal of Adult Development, 23, 1–10. 10.1007/s10804-015-9216-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assad KK, Donnellan MB, & Conger RD (2007). Optimism: An enduring resource for romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 285–297. 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auslander BA, Short MB, Succop PA, & Rosenthal SL (2009). Associations between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Romantic Relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 98–101. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers W, & Goossens L (2008). Dynamics of perceived parenting and identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 165–184. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, & Beach SRH (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the FamilyFamily, 62, 964–980. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00964.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braiker H, & Kelley HH (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships In Burgess RL & Huston TL (Eds.), Social Exchange in Developing Relationships (pp. 135–168). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, & Conger RD (2002). An intergenerational model of romantic relationship development In Vangelisti AL, REIS HT, & Fitzpatrick MA (Eds.), Stability and Change in Relationships (pp. 57–82). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359, 1331–1336. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Badger S, & Yang C (2006). The ability to negotiate or the ability to love? Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1001–1032. 10.1177/0192513X06287248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, & Catherine M-C (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598–606. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating Goodness-of- Fit Indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9, 233–255. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, & Smith PH (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 260–268. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JA, & Johnson AM (1996). Adolescents’ romantic relationships and the structure and quality of their close interpersonal ties. Personal Relationships, 3, 185–195. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00111.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current directions in psychological science, 12, 193–196. 10.1111/1467-8721.01259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, & Booth A (2003). Children’s infuence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. (Crouter AC & Booth A, Eds.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 10.1207/s15327965pli0904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, & Fincham FD (2010). The differential effects of parental divorce and marital conflict on young adult romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17, 331–343. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01279.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Cohan CL, Burns A, & Thompson L (2008). Within-family conflict behaviors as predictors of conflict in adolescent romantic relations. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 671–690. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Steinberg SJ, Miller MR, Stroud CB, Starr LR, & Yoneda A (2009). Assessing romantic competence in adolescence: The Romantic Competence Interview. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 55–75. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110, 173–192. 10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillow MR, Goodboy AK, & Bolkan S (2014). Attachment and the expression of affection in romantic relationships: The mediating role of romantic love. Communication Reports, 27, 102–115. 10.1080/08934215.2014.900096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Patterson GR (2006). The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents In Cicchetti D & Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology, Vol 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. (pp. 503–541). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc5&NEWS=N&AN=2006-03609-013 [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Larsen-Rife D, & Conger RD (2005). Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 562–576. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK, & Amato PR (2005). Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 607–627. 10.1177/0265407505056438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eğeci İS, & Gençöz T (2006). Factors associated with relationship satisfaction: Importance of communication skills. Contemporary Family Therapy, 28, 383–391. 10.1007/s10591-006-9010-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eskin M (2003). Self-reported assertiveness in Swedish and Turkish adolescents: A cross-cultural comparison. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44, 7–12. 10.1111/1467-9450.t01-1-00315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME (2002). Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 173–195. 10.1038/jid.2014.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman CM, & Ridley CA (2000). The role of conflict-based communication responses and outcomes in male domestic violence toward female partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 552–573. 10.1177/0265407500174005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, & Cui M (2011). Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (Fincham FD & Cui M, Eds.). New York: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511761935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, & Cleveland HH (2007). Linking family functioning to dating relationship quality via novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance personality pathways. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 575–590. 10.1177/0265407507079257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Lippold M, & Feinberg ME (2014). Interparental boundary problems, parent–adolescent hostility, and adolescent–parent hostility: A family process model for adolescent aggression problems. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 3, 141–155. 10.1037/cfp0000025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Van Ryzin MJ, Xia M, & Feinberg ME (2016). Trajectories of adolescent hostile-aggressive behavior and family climate: Longitudinal implications for young adult romantic relationship competence. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1139–1150. 10.1037/dev0000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, & Roisman GI (2015). Do early caregiving experiences leave an enduring or transient mark on developmental adaptation? Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 101–106. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gambrill ED, & Richey CA (1975). An assertion inventory for use in assessment and research. Behavior Therapy, 6, 550–561. 10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80013-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]