Abstract

Objectives

Given that prior mistreatment can lead to heightened vigilance to and perceptions of future rejection, the present study examined whether this heightened vigilance, known as rejection sensitivity, mediates the association between healthcare mistreatment and healthcare avoidance in trans masculine (TM) adults.

Method

Between 2015 and 2016, 150 TM adults completed a comprehensive survey assessing socio-demographics, sexual health, and healthcare experiences. A 5-item scale assessing participants’ sensitivity to rejection in healthcare scenarios was administered and psychometrically evaluated. Structural equation modeling was used to test whether rejection sensitivity in healthcare mediated the relationship between lifetime mistreatment in healthcare and past 12-month healthcare avoidance among TM adults.

Results

Overall, 68% of participants had experienced some form of mistreatment in healthcare in their lifetime and 43% had avoided healthcare in the past 12 months. For 5% of the sample, healthcare avoidance in the past 12 months resulted in a medical emergency. Path analyses revealed that healthcare mistreatment was positively correlated with rejection sensitivity and sensitivity was positively correlated with past 12-month healthcare avoidance. Rejection sensitivity mediated the relationship between mistreatment and healthcare avoidance (all p-values < 0.05).

Conclusion

Rejection sensitivity may contribute to healthcare avoidance among stigmatized TM patients; however, longitudinal research is needed to establish the temporal ordering of these processes. Multilevel interventions to reduce healthcare discrimination and help TM adults cope with the psychological and behavioral consequences of stigma are recommended.

Keywords: transgender, rejection sensitivity, stigma, healthcare, scale development

Introduction

Trans masculine (TM) is a term utilized to describe an array of individuals who were assigned a female sex at birth and who now identify as men, trans men, male, or another binary or non-binary (e.g., genderqueer) identity along the female-to-male gender spectrum. Like all people, TM individuals need to access healthcare to meet their general, emergency, and preventative healthcare needs, including routine primary and sexual healthcare such as chest exams and Pap tests to screen for sexually transmitted infections and cancer. Many TM individuals also require healthcare to medically affirm their gender, which can include the use of hormone therapy and/or surgery to align one’s gender presentation with one’s gender identity (Coleman et al., 2012). However, due to having a gender expression or identity that does not conform to the socially sanctioned gender norms of their birth sex, TM people often experience widespread stigma, which can impact their access to healthcare and ultimately lead to poor health outcomes (White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015).

Mistreatment in Healthcare Settings

Transgender stigma in healthcare can include overt, enacted discrimination such as being refused care by a healthcare provider, as well as more subtle or even inadvertent forms of stigma, such as a provider’s use of non-affirming language and lack of transgender health knowledge (James et al., 2016; Lurie, 2005; Poteat, German, & Kerrigan, 2013; White Hughto et al., 2015). Lack of provider knowledge can force TM patients to have to educate their providers, and may even lead providers to perform unnecessary exams, such as pelvic exams, out of curiosity (Poteat et al., 2013; Snelgrove, Jasudavisius, Rowe, Head, & Bauer, 2012; White Hughto et al., 2015). Discriminatory encounters and unnecessary and invasive questions or procedures can be traumatic for TM patients, particularly for those who are highly gender dysphoric (Agénor et al., 2016; Coleman et al., 2012; Reisner, Randazzo, et al., 2017). Moreover, research suggests that TM individuals often avoid healthcare for fear of mistreatment, which can lead to otherwise preventable healthcare emergencies (Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015; Reisner, Pardo, et al., 2015).

Rejection Sensitivity and Mistreatment

The rejection sensitivity model is a useful framework for understanding how past experiences of mistreatment may shape future health behaviors for TM individuals and other marginalized groups. The rejection sensitivity model was first developed by Mendoza-Denton et al. (2002) to elucidate how sensitivity to race-related rejection impacts the interpersonal functioning and mental health of African American college students, and later adapted to examine how experiencing homophobia in everyday interpersonal situations can contribute to anxious expectations of rejection and internalized homophobia in gay men (Pachankis, Goldfried, & Ramrattan, 2008). The model posits that heightened sensitivity to mistreatment develops out of interpersonal schemas derived from past experiences of discrimination or community narratives of stigmatizing encounters. These interpersonal schemas of mistreatment can lead stigmatized individuals to nervously anticipate, routinely observe, and anxiously react to rejection (Mendoza-Denton, Downey, Purdie, Davis, & Pietrzak, 2002). Rejection sensitivity therefore incorporates an individual’s evaluation of whether rejection is likely to occur in the future (i.e., expectations of rejection) and one’s propensity to anxiously respond to stigmatizing encounters.

The term sensitivity is not meant to further stigmatize marginalized groups, but rather to illustrate the variability in stigmatized individuals’ reactions to stigma. Rejection sensitivity occurs along a continuum, anchored by accurate threat perception and adaptive emotional reactions at one end and inaccurate threat perception and maladaptive emotional reactions at the other (Downey, Freitas, Michaelis, & Khouri, 1998). Take for example a transgender patient who has been asked to provide a urine sample during a routine health exam. The medical assistant directs the patient to the “unisex bathroom” because it is the only bathroom in the lab area. A transgender patient with inaccurate threat perception might assume that that he was singled out to use the unisex bathroom due to his gender identity and subsequently avoid future health exams at the clinic on the basis that the staff are transphobic. Conversely, a transgender patient with accurate threat perception would scan the lab area, determine that it is the only bathroom, and later return for future health screenings at the clinic in order to safeguard his health. Now had there been gendered and unisex bathrooms in the lab area, and had the medical assistant indicated that she always directs transgender people to single occupant bathrooms so as not to “alarm other patients,” than the patient’s decision to avoid future health screenings at the clinic would have been an accurate and adaptive response to transphobia. Thus, accurately perceiving and adaptively responding to mistreatment is protective as it enables stigmatized individuals to avoid harm. However, heightened sensitivity to rejection can be problematic when it leads stigmatized individuals to interpret benign situations as discriminatory and respond in harmful or self-defeating ways.

Extending the rejection sensitivity model to TM individuals, researchers have theorized that rejection sensitivity mediates the relationship between experiences of healthcare mistreatment and healthcare avoidance (White Hughto et al., 2015). Indeed, it has been theorized that TM adults who have experienced mistreatment in healthcare may develop a heightened sensitivity to future rejection in these settings, which leads to anxious expectations of future mistreatment and avoidance of healthcare as a means of coping with the perceived threat. While researchers have theorized that rejection sensitivity may be one of the psychological processes through which stigma harms the health of TM individuals (e.g., White Hughto et al, 2015), to date, no study to our knowledge, has examined the mediating role of rejection sensitivity in this population, particularly in important settings like healthcare where stigma is common and the consequences of behavioral avoidance can be dire.

Aims

In order to examine rejection sensitivity among transgender people in healthcare encounters, it is first necessary to establish a psychometrically sound assessment of this construct. Building on the gay-related rejection sensitivity scale developed by Pachankis et al. (2008), the present study aimed to establish a valid and reliable measure of rejection sensitivity among transgender people in healthcare settings and then test the hypothesis that rejection sensitivity mediates the relationship between healthcare mistreatment and healthcare avoidance among TM adults. Demonstrating the mediating role of rejection sensitivity in the relationship between past experiences of healthcare mistreatment and future healthcare avoidance can serve to further validate the theory of rejection sensitivity among TM adults and pave the way for the development of interventions that target problematic psychological and behavioral reactions to stigma in order to improve access to healthcare and ultimately the health of TM adults.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The present study utilized data collected from a sample of 150 TM adults who were enrolled in a sexual health study between March 2015 and September 2016. The primary aim of the parent study was to evaluate self-swab testing for cervical human papillomavirus (HPV). The parent study also examined facilitators and barriers to healthcare, including HPV testing. Participants were purposively sampled through recruitment at the clinic where the study was conducted, flyers posted at community-based organizations serving transgender individuals, online social networks, and word of mouth. Eligible participants were: (1) ages 21 to 64; (2) assigned a female sex at birth and now have a masculine-spectrum gender identity; (3) have a cervix; (4) have been sexually active within the past 3 years with partners of any gender; (5) able to speak and understand English; and (6) willing and able to provide informed consent.

The parent study included a clinical visit and a self-administered survey assessing participant demographics, sexual health, mental health, and healthcare experiences, including past experiences of discrimination and rejection sensitivity (see Reisner et al., 2017 for study protocol). All participants received a $100 gift card for their time. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fenway Health.

This paper utilizes data collected during the self-administered survey to develop and test the rejection sensitivity construct as applied to the healthcare experiences of transgender adults.

Measures

Descriptive variables

Socio-demographics

Participants’ age was assessed continuously in years. Participants were asked to check all that apply regarding their race: White; American Indian/Alaskan Native; Asian; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; Black/African American; another race. Participants reporting more than one race were coded as such. Participants with a race other than White were coded as being a person of color (1= yes, 0 = no). Participants were asked whether they were Hispanic or Latino (1= yes, 0 = no). Annual income was assessed continuously with a “don’t know” and “prefer not to answer” option, and low annual income was coded as: $32,000 or less vs. $32,000 or more.

Participants were provided with a list of responses and asked to “choose the response that best describes your gender identity today.” Participants had the option of writing in an identity not otherwise provided. Participants who identified as a man, male, transgender man, female-to-male (FtM), trans man, man of transgender experience, trans masculine or another binary gender not otherwise listed (e.g., trans, masculine of center) were coded as having a binary gender identity. Participants who identified as genderqueer, gender non-conforming, non-binary, or another non-binary gender identity not otherwise listed (e.g., two-spirit) were coded as non-binary. Participants were asked if they were currently using hormones (1= yes, 0 = no) or had surgery (1= yes, 0 = no) to affirm their gender.

Health consequences of healthcare avoidance

In order to characterize the health consequences of healthcare avoidance, participants were also asked to indicate if they had avoided healthcare in the past 12 months to the point that it resulted in a medical emergency (1 = yes, 0 = no) (Grant et al., 2011).

Validity measures

In order to assess the validity of the rejection sensitivity scale, we selected five measures hypothesized to be significantly (convergent validity) and non-significantly (divergent validity) correlated with rejection sensitivity for transgender individuals. Transgender-related discrimination was selected as a convergent validity measure given prior research documenting a significant and positive correlation between status-based discrimination and rejection sensitivity (Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002; Pachankis et al., 2008). Anxiety was selected as a convergent validity measure because prior research has conceptualized and measured rejection sensitivity as anxious expectations of rejection (Downey & Feldman, 1996; London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002; Pachankis et al., 2008) and rejection sensitivity has been linked to anxiety in other marginalized groups (Luterek, Harb, Heimberg, & Marx, 2004; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002; Pachankis et al., 2008). Resilience was chosen as the third convergent validity measure given prior research demonstrating a negative relationship between resilience and poor mental health among transgender individuals (Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013). Finally, past week fruit consumption and sex drive were chosen as divergent validity measures as no prior research has documented a relationship between rejection sensitivity and these experiences.

Transgender-related discrimination

Transgender-related discrimination experiences were assessed with the 11-item Everyday Discrimination Scale, which assesses the frequency of participants’ experiences of everyday discrimination in the past 12 months on a Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 4 = very often. Sample items include: “You have been treated with less courtesy than other people;” “You have received poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores” (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005; Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Participants were then asked to indicate the reason(s) attributed to their discrimination experiences. Items from the general everyday discrimination scale were summed. In order to create a transgender-specific discrimination score, participants who did not report experiencing discrimination due to some aspect of being transgender (e.g., gender identity or expression) were given a score of 0. Scores for the transgender-related discrimination score ranged from 0 to 39, with higher scores indicating higher levels of transgender-related discrimination. Reliability for the current measure was excellent (α = .94; M = 12.51; SD = 9.13) (Gliem & Gliem, 2003). In previous research with transgender people, scores on the general scale ranged from 0 to 44 (M = 19.88; SD = 9.58) and internal consistency was also excellent (α = .93) (White Hughto, Pachankis, Willie, & Reisner, 2017). In prior samples of sexual and gender minority participants, general discrimination scores were positively correlated with depressive distress, anxiety, and substance use (Gamarel, Reisner, Laurenceau, Nemoto, & Operario, 2014; Gamarel, Reisner, Parsons, & Golub, 2012; Gordon & Meyer, 2008; Reisner, Gamarel, Nemoto, & Operario, 2014).

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety was assessed via the anxiety symptoms subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18). The six-item subscale assesses how distressed or bothered participants are by anxiety symptoms (e.g., “Nervousness or shakiness inside”) in the last 7 days on a scale from 0 = not at all to 5 = extremely bothered (Derogatis, 2000). Items were summed and anxiety scores ranged from 39 to 81, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety (M = 56.01; SD = 10.13). Mean anxiety scores for the present sample correspond to the 73rd percentile of the anxiety scores for cisgender men and women combined (Derogatis, 2000). Reliability for the present study was good (α = .88) and consistent with previous studies of transgender adults (i.e., .89) (Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013) and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth (i.e., .91 – .94) (Reuter, Newcomb, Whitton, & Mustanski, 2017).

Resilience

Resilience was assessed using four items from the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008). Responses were assessed on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree and included items such as “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” Appropriate item responses were reverse scored and averaged to derive a single scale score. Higher scores indicated greater ability to recover from stress. Reliability for the present study was good (α = .86) and participants reported moderate mean levels of resilience (M = 3.26; SD = 0.81). In previous research with transgender adults, internal consistency was slightly better than the present study (α = . 91), mean scores were slightly lower, (M = 2.90; SD = 0.94), and resilience was negatively correlated with psychological distress (Breslow et al., 2015).

Fruit consumption

A single item was used to assess on how many days in the past seven days participants had consumed fruit (M = 4.25; SD = 2.13) (Eaton et al., 2013).

Sex drive

Sex drive was assessed by asking participants to rate their level of sexual desire or interest in the past four weeks (Rosen, 2000). Responses options ranged from 1 = very low/ none at all to 5 = very high. The mean sex drive score was 3.61 (SD = 1.07) in the current sample. In studies of cisgender heterosexual and lesbian women, sexual desire was positively correlated with arousal and sexual satisfaction (Beaber & Werner, 2009; Rosen, 2000) and no differences were found in level of desire by sexual orientation (Beaber & Werner, 2009).

Variables used in mediation analyses

Mistreatment in healthcare

Lifetime mistreatment in healthcare due to one’s gender identity was assessed using two measures from previous research with transgender samples (Grant et al., 2011; Reisner, Pardo, et al., 2015). Specifically, participants were asked to indicate (1 = yes or 0 = no) whether they had the following experiences in their lifetime: “Due to my transgender identity or nonconforming gender expression, a doctor or other provider refused to treat me” and “I had to teach my doctor or other healthcare provider about transgender people in order to get appropriate care” (response options: 1 = yes, 0 = no). In the present study, 10.0% of the sample had been refused care in their lifetime and 68.0% had to teach their doctor in order to receive appropriate care during their lifetime. In previous studies with transgender samples (James et al., 2016; Reisner, Pardo, et al., 2015)., healthcare refusal (5.8%-14.1%) and educating one’s provider in order to receive appropriate care (24.0%-32.1%) were common and these forms of mistreatment were each positively associated with being unable to access medical gender affirmation care (e.g., hormones or surgery) (White Hughto, Rose, Pachankis, & Reisner, 2017).

Healthcare avoidance

Healthcare avoidance in the past 12 months was measured by asking respondents to answer 1 = yes or 0 = no to the following three experiences (Grant et al., 2011): “I postponed or did not try to get medical care when I was sick or injured;” “I postponed or did not try to get checkups or other preventive medical care;” and “I postponed or did not get sexual healthcare.” In the present study, 26.7% of the sample had avoided preventative healthcare; 28.0% had avoided emergency healthcare; and 28.7% had avoided sexual healthcare in the past 12 months. In prior research with transgender samples, healthcare avoidance was common (past 12 months = 19.3%-23.7%; lifetime = 30.3%) (James et al., 2016; Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015; White Hughto, Murchison, Clark, Pachankis, & Reisner, 2016).

Transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare (TRS-H)

Drawing on the framework first developed by Mendoza-Denton et al. (2002) for African American students and later adapted by Pachankis et al. (2008) for gay men, five items were developed to assess transphobia-related rejection sensitivity among transgender adults in healthcare contexts. The items were generated through qualitative interviews with transgender people assessing their healthcare experiences (Poteat et al., 2013; Reisner, Randazzo, et al., 2017); reports of transgender patient complaints from a community health center; and expert feedback from transgender community members and researchers and physicians with expertise in transgender health. An initial list of 10 items were created that focused on five healthcare domains: Gendered Healthcare Spaces (i.e., restrooms); Physical Exams; HIV Testing; the Emergency Room; and Healthcare Referrals. Two transgender-identified researchers, two transgender-identified community members, and two cisgender physicians working in transgender health reviewed the original 10-item measure and found it to be too long and redundant. Through consultation with two psychologists with expertise in measurement development and familiarity with the rejection sensitivity construct and transgender health, it was determined that while shortening the measure could reduce its reliability, the face validity and acceptability of the measure in the field would likely be improved if it were to be shortened. Based on these considerations, the measure was reduced to five items (one item per domain).

As shown in Table 1, the five items were administered to participants followed by two response stems. Participants were first asked to indicate how likely a specific situation would be to occur due to their gender identity or expression (1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely) and how concerned/anxious they would be that the situation occurred because of their gender identity or expression (1 = very unconcerned, 5 = very concerned). Following the lead of Mendoza-Denton et al. (2002) and Pachankis et al. (2008), the likelihood and anxiety scores were combined into a Likelihood-by-Anxiety score. To arrive at this score, the product of the Likelihood and Anxiety subscales was calculated for each item and the sum of the five resulting scores was divided by five.

Table 1.

Transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare (TRS-H) measure.

|

Each of the items below

describes situations that people encounter in healthcare settings.

Sometimes these situations occur because a person is transgender or

gender non-conforming, sometimes they occur for other reasons. Some

people are concerned about these situations and others are not.

Please imagine yourself in each situation and indicate how you would

feel if this situation happened to you because you are transgender

or gender non-conforming. | |||||

| 1. You have to provide a urine sample for a routine health exam. When you ask the medical assistant where the bathroom is, she tells you where the unisex bathroom is located. | |||||

| How likely is it that the medical assistant told you where the unisex bathroom is located because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| How concerned/anxious would you be if the medical assistant told you where the unisex bathroom is located because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unconcerned | Very Concerned | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 2. You switch to a new primary care doctor and he recommends that you get a full physical exam even though you had a physical exam last year. | |||||

| How likely is it that your doctor recommended you get a full physical exam because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| How concerned/anxious would you be if your doctor recommended you get a full physical exam because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unconcerned | Very Concerned | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 3. You are going to have surgery and the doctor tells you that he would like to give you an HIV test. | |||||

| How likely is it that the doctor would like to give you an HIV test because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| How concerned/anxious would you be if the doctor would like to give you an HIV test because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unconcerned | Very Concerned | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 4. You go to the emergency room with terrible pains in your abdomen. Five other people arrive after you and all of them are seen before you are. | |||||

| How likely is it that five other people were seen before you were because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| How concerned/anxious would you be if five other people were seen before you were because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unconcerned | Very Concerned | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 5. You ask your primary care doctor for a referral to a good surgeon. She says she will call you in one week with a referral, but she does not. | |||||

| How likely is it that your doctor does not call you with the referral because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| How concerned/anxious would you be if your doctor does not call you with the referral because you are transgender or gender non-conforming? | Very Unconcerned | Very Concerned | |||

Because no a priori assumptions guided the possible factor structure of this measure, an exploratory principal components factor analysis was performed to determine the underlying structure of the five items. A one-factor solution was identified based on the scree plot test and the number of factors with an Eigen value greater than one. The factor accounted for 49.8% of the variance and the scale demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .75). Table 2 orders the five items of the TRS-H by factor loading.

Table 2.

Transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare (TRS-H) items and factor loadings.

| Item | Loading |

|---|---|

| You go to the emergency room with terrible pains in your abdomen. Five other people arrive after you and all of them are seen before you are. | 0.77 |

| You switch to a new primary care doctor and he recommends that you get a full physical exam even though you had a physical exam last year. | 0.73 |

| You are going to have surgery and the doctor tells you that he would like to give you an HIV test. | 0.72 |

| You ask your primary care doctor for a referral to a good surgeon. She says she will call you in one week with a referral, but she does not. | 0.71 |

| You have to provide a urine sample for a routine health exam. When you ask the medical assistant where the bathroom is, she tells you where the unisex bathroom is located. | 0.59 |

Next, the convergent and discriminant validity of the TRS-H scale was established. In order to test convergent validity, anxiety symptoms, transgender discrimination, and resilience were hypothesized to yield moderate correlations with the TRS-H scale. In testing discriminant validity, the TRS-H scale was hypothesized to be unrelated to fruit consumption and sex drive. As expected, the TRS-H scale was moderately and positively correlated with anxiety and transgender discrimination and negatively correlated with resilience (see Table 3). These significant correlations suggests that anxiety symptoms, transgender discrimination, and resilience are not interchangeable with the TRS-H scale; that there is a substantial amount of remaining variance in relevant criteria variables to be accounted for by the TRS-H scale; and that this variance is not accounted for by general anxiety, transgender discrimination, or lack of resilience in the face of stress. Consistent with our discriminant validity hypotheses, no relationships were found between the TRS-H and fruit consumption or sex drive.

Table 3.

Correlations demonstrating convergent and divergent validity between the transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare (TRS-H) scale and key variables.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TRS-H | 1 | 0.22** | 0.23** | −0.24** | −0.06 | −0.001 | 0.25** | 0.22** |

| 2. Anxiety Symptoms | 1 | .44** | −.46** | −0.01 | −0.11 | .26** | .24** | |

| 3. Transgender-Related Discrimination | 1 | −.20* | −0.02 | 0.004 | .18* | .26** | ||

| 4. Resilience | 1 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.15 | −.19* | |||

| 5. Fruit Consumption | 1 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.02 | ||||

| 6. Sex Drive | 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||||

| 7. Mistreatment in Healthcare | 1 | .17* | ||||||

| 8. Healthcare Avoidance | 1 |

p <05.

p <.01

When exploring the correlations between variables other than the TRS-H scale, as anticipated, transgender discrimination and anxiety were positively correlated with one another and with healthcare avoidance and mistreatment. Correlations between resilience and other variables were also in the anticipated direction as resilience was negatively correlated with transgender discrimination and anxiety as well as healthcare avoidance. As expected, fruit consumption and sex drive were not correlated with any other variables (Table 3).

Data Analytic Plan

Using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., 2014), distributions of individual items were assessed, including missingness. Across the sample of 150 participants, two participants had missing data for both measures of healthcare mistreatment and all rejection sensitivity items and were thus excluded from the sample. All subsequent analyses were based on an analytic sample of n=148.

Description of the sample

Univariate descriptive statistics were used to summarize the overall distribution of participant characteristics, healthcare experiences, and the rejection sensitivity measure and its composite items. Bivariate regression models were used to examine associations between participant age, race, gender identity, income, and rejection sensitivity.

Tests of mediation

After establishing the internal reliability and scale structure of the TRS-H scale, structural equation modeling in AMOS 23 was used to test the hypothesis that mistreatment in healthcare (X) is indirectly and positively associated with past 12-month healthcare avoidance (Y) through rejection sensitivity (M). Since three items are recommended when modeling a latent variable (Weston & Gore, 2006), a dichotomous variable of lifetime healthcare mistreatment was created, where participants who answered yes to one or both types of mistreatment were coded as 1, otherwise 0. A latent variable of healthcare avoidance was created using the three items assessing avoidance in various contexts (i.e., emergency care, routine care, sexual healthcare).

Following the recommendations of Weston and Gore (2006), a mediation model with direct paths from mistreatment to rejection sensitivity and from rejection sensitivity to healthcare avoidance was tested first (full mediation model). The full mediation model did not have a direct path from mistreatment to healthcare avoidance. Next, a partial mediation model, which included direct paths from mistreatment to healthcare avoidance, was tested. To determine the fit of the hypothesized models, the following fit indices were examined: non-normed fit index (NFI) and comparative fit index (CFI; .90 – .95 = acceptable; > .95=excellent); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA: .06 – .08 = acceptable; < .06 = excellent); the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR: .05 – .09 = acceptable; < .05 = excellent); and the chi-square test (p > 0.05 = excellent) (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003). Because the partial model was nested in the full model, the best fitting model was determined by performing a chi-square difference test (p < 0.05 = better fit) (Weston & Gore, 2006) as well as comparing the Bayesian information Criterion (BIC) of the full and partial models (lower = better fit).

Bootstrapping was used to test the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediated) association of mistreatment on healthcare avoidance (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). A total of 2,000 random samples were generated from the dataset to construct a 95% standardized confidence interval for the mediated association of mistreatment on healthcare avoidance through rejection sensitivity. The amount of variability (R2) in the latent outcome variable that was accounted for by the model and the model fit statistics (i.e., NFI, CFI, RMSEA, SRMR, X2) were also examined.

Results

Description of the Sample

As shown in Table 4, participants’ mean age was 27.5 (SD=5.7) and 75.7% of the sample was White. Nearly half the sample (49.3%) had an annual income of less than $32,000 a year. The majority of the sample (76.7%) had a binary gender identity (e.g., man, transgender man), 76.0% were currently on hormones, and 40.0% had affirmed their gender through surgery. Additionally, 68.7% had experienced some form of mistreatment in healthcare in their lifetime and 47.3% had avoided one or more form of healthcare in the past year. A total of 5.3% of the sample reported that their avoidance of needed healthcare in the past 12 months resulted in a medical emergency.

Table 4.

Socio-demographics and healthcare experiences of trans masculine adults (N=150).

| Age, continuous | Mean | SD |

| Range: 21–50 years | 27.5 | 5.7 |

| Race | N | % |

|

|

||

| White | 112 | 74.7 |

| Person of Color | 38 | 25.3 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asian | 9 | 6.0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.7 |

| Black or African American | 4 | 2.7 |

| More than one race | 24 | 16.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 | 9.3 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 133 | 88.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 2.0 |

| Low Annual Income | ||

| $32,000 or less | 74 | 49.3 |

| >$32,000 | 60 | 40.0 |

| Don’t know | 13 | 8.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 2.0 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Binary | 115 | 76.7 |

| Non-binary | 35 | 23.3 |

| Hormone Use - Current | ||

| No | 37 | 24.7 |

| Yes | 113 | 75.3 |

| Gender Affirmation Surgeries | ||

| No | 90 | 60.0 |

| Yes | 60 | 40.0 |

| Visual Gender Conformity | ||

| Low | 75 | 50.0 |

| Med | 44 | 29.3 |

| High | 24 | 16.0 |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 | 4.7 |

| Mistreatment in Healthcare - Lifetime | ||

| Any | 103 | 68.7 |

| Refused care by a healthcare provider | 15 | 10.0 |

| Taught doctor in order to receive appropriate care | 102 | 68.0 |

| Healthcare Avoidance - Past 12 Months | ||

| Any | 71 | 47.3 |

| Avoided emergency healthcare | 42 | 28.0 |

| Avoided preventative healthcare | 40 | 26.7 |

| Avoided sexual healthcare | 43 | 28.7 |

| Healthcare Avoidance Resulted in Medical Emergency - | ||

| Past 12 Months | ||

| No | 142 | 94.7 |

| Yes | 8 | 5.3 |

After establishing the psychometric properties of the TRS-H as reported above, the overall endorsement of the scale items in our sample was examined. Using the likelihood stem of the TRS-H, participants indicated a moderate level of likelihood for experiencing the five healthcare scenarios with a mean agreement across items of 2.45 out of 5 (SD = 1.27). Participants expressed the lowest agreement with the item, “How likely is it that your doctor does not call you with the referral because you are transgender or gender non-conforming” (M = 1.91, SD = 1.16) and the highest agreement with the item, “How likely is it that the medical assistant told you where the unisex bathroom is located because you are transgender or gender non-conforming” (M = 2.85, SD = 1.35). Using the anxiety stem, participants reported a relatively high degree of anticipated anxiety based on the five TRS-H items. The mean anxiety reported from the five items was 3.46 out of 5 (SD = 1.36). Participants expressed the lowest anticipated anxiety from the item, “How concerned/anxious would you be if the medical assistant told you where the unisex bathroom is located because you are transgender or gender non-conforming” (M = 2.20, SD = 1.33) and the highest anxiety from the item, “How concerned/anxious would you be if five other people were seen before you in the emergency room because you are transgender or gender non-conforming?” (M = 4.35, SD = 1.19). Rejection sensitivity was not significantly related to age, race, gender identity, or income.

Tests of Mediation

The full mediation model demonstrated adequate fit: X2 = 9.45 (df = 5), p = .09; NFI = .90; CFI = .95; RMSEA =.08; SRMR = .05. The full model accounted for 40.7% of the variance in rejection sensitivity and 60.1% of the variance in healthcare avoidance. The fit for the partial mediation model was similar to the full model: X2 = 8.45 (df = 4), p = .08; NFI = .91; CFI = .95; RMSEA =.09; SRMR = .04. The partial model accounted for 40.7% of the variance in rejection sensitivity and 60.9% of the variance in healthcare avoidance. While the difference between the two models was not significant: Δ X2 (df = 1) = 1.00, p < .50, the full mediation model had a lowed BIC (59.56) relative to partial model (63.46) and thus the full mediation model was retained for testing the hypothesized mediation.

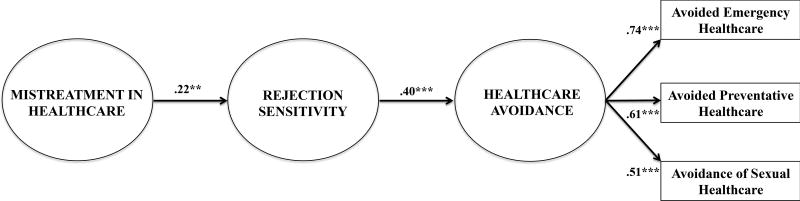

Figure 1 depicts the final mediation model testing whether participants’ transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare contexts mediates the association between lifetime experiences of mistreatment in healthcare and healthcare avoidance in the past 12 months. As hypothesized, a significant positive association was found between lifetime experiences of mistreatment in healthcare and rejection sensitivity (B = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.07, 0.34, p = 0.01) and a significant positive association was found between rejection sensitivity and past 12-month healthcare avoidance (B = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.23, 0.55, p < 0.01). Additionally, there was a significant indirect effect of healthcare mistreatment on healthcare avoidance through rejection sensitivity (B = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.17, p < 0.01), demonstrating that rejection sensitivity fully mediates the relationship between mistreatment and avoidance in healthcare settings.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model depicting transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare (TRS-H) as a full mediator of the association between mistreatment in healthcare and healthcare avoidance in a sample of TM adults.

**p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Indirect Effect = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.17, p < 0.01;

Model fit: X2 = 9.45 (df = 5), p = .09; NFI = .90; CFI = .95; RMSEA =.08; SRMR = .05.

Discussion

While TM adults have been shown to avoid healthcare due to fear of mistreatment (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016; Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015; White Hughto et al., 2016), a dearth of empirical research has examined the psychological processes (i.e., anxious expectations of rejection) through which mistreatment is associated with healthcare avoidance in this population. Understanding the psychological mechanisms linking mistreatment to avoidance is critical for future interventions that seek to increase uptake and utilization of routine and preventive healthcare among TM adults. The present study finds evidence that transphobia-related rejection sensitivity might represent one such process with important implications for TM adults’ health.

Rejection sensitivity refers to an individual’s level of anticipation and perception of rejection or mistreatment. This study describes the development of a measure of the rejection sensitivity as applied to TM adults in healthcare contexts, including interpersonal interactions in the emergency room, during physical exams, in the context of HIV testing, and when navigating healthcare facility spaces. The measure demonstrated good convergent validity (i.e., TRS-H was positively correlated with anxiety and transgender-related discrimination and negatively correlated with resilience) and divergent validity (i.e., TRS-H was not significantly correlated with fruit consumption or sex drive), suggesting that transphobia-related rejection sensitivity in healthcare contexts is not already captured by other measures. Further validating this new construct as applied to TM adults, the present study found a medium indirect effect from healthcare mistreatment to healthcare avoidance (Preacher & Kelley, 2011), thus providing evidence that rejection sensitivity mediates the association between TM adults’ past experiences of mistreatment in healthcare and healthcare avoidance. While this study represents the first time that rejection sensitivity has been shown to mediate the relationship between status-based rejection and healthcare avoidance in TM adults or any population, prior research with gay men also found that rejection sensitivity was a full mediator of the relationship between past experiences of rejection from one’s parents) and psychological reactions to rejection (i.e., internalized homophobia) (Pachankis et al., 2008). Similarly, a study of college students found that rejection sensitivity fully mediated the relationship between exposure to family violence as a child and avoidant and ambivalent patterns of insecure adult attachment behavior (Feldman & Downey, 1994). Building upon prior theoretical models of transgender stigma (White Hughto et al., 2015) and empirical tests of rejection sensitivity with other groups (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Feldman & Downey, 1994; London et al., 2007; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002; Pachankis et al., 2008), these findings suggest that TM adults’ experiences of mistreatment in healthcare might psychologically prime TM adults to expect and anxiously react to potentially stigmatizing interactions in future healthcare contexts and ultimately lead to the outright avoidance of healthcare. Findings point to the need for multilevel interventions to prevent discrimination and its subsequent hypervigilance to rejection and anxious avoidance of healthcare in this at-risk population.

Interpersonal schemas formed through experiences of discrimination can be health-promoting when they allow stigmatized individuals to accurately identify threatening situations and avoid future discrimination. However, these schemas can become rigid guides for interpreting new or ambiguous situations and can therefore lead stigmatized individuals to interpret benign situations as harmful and respond in ways that ultimately diminish health (Cloitre, Cohen, & Scarvalone, 2002; Scarvalone, Fox, & Safran, 2005; Starks, Payton, Golub, Weinberger, & Parsons, 2014) For instance, over-general expectations of discrimination based on personal schemas of discrimination can lead stigmatized individuals to avoid healthcare even from new, supportive providers, which could lead to otherwise preventable medical emergencies. Clinical interventions can help stigmatized individuals high in rejection sensitivity to cognitively re-process ambiguous, but benign events as less threatening through the creation of new interpersonal schemas. Such interventions have shown success in other marginalized populations (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, & Parsons, 2015) and may hold promise for reducing rejection sensitivity and avoidant coping responses in TM adults. However, it is important to note that many interpersonal situations do pose a clear threat for victimization for transgender individuals, thus clinicians should also work with TM clients to develop alternative coping strategies that enable access to health-promoting resources in safe, affirming contexts (APA, 2015). For example, TM individuals who have experienced victimization may benefit from interventions that help them to respond to the fear of future mistreatment by recognizing their inherent strengths and developing skills to prevent or manage stigmatizing experiences through less avoidant means (Hash & Rogers, 2013; Sikkema et al., 2013). There is no evidence to suggest that there must me an identity match (e.g., same race, same gender) between therapists and clients in order for clinical interventions to be effective (Cabral & Smith, 2011; Flaskerud, 1990); however, research documents the positive effect of transgender affirming psychological care (see APA, 2015 for a review). Thus, stigma coping interventions are likely to have the most optimal benefit for transgender patients when delivered by therapists who are capable of empowering and validating patient’s identity and experiences through culturally competent and supportive care (APA, 2015).

Finally, it should be noted that while rejection sensitivity may develop in response to mistreatment, and can be attenuated through psychotherapy (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, et al., 2015), having a heightened awareness to threat perception is in no way the fault of the individual. Rather, the social learning processes described here ultimately represent a response to the common experience of being mistreated due one’s gender identity or expression. Thus, while individual-level interventions play an important role in helping marginalized individuals cope with past or anticipated experiences of mistreatment, structural (e.g., laws and policies) and interpersonal (e.g., efforts targeting the beliefs and behaviors of non-transgender people) interventions are also needed to reduce transgender stigma at its source. These interventions might include structural efforts to pass and enforce non-discrimination policies that make it illegal to discriminate on the basis of gender identity (Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015) or cultural and clinical competence trainings that seek to reduce interpersonal stigma by improving healthcare providers’ capacity to provide quality, gender-affirming care to transgender patients (White Hughto, Clark, et al., 2017). By addressing societal stigma as a fundamental cause of the mistreatment that many transgender people experience in healthcare settings, structural and interpersonal interventions can ultimately help to prevent mistreatment in healthcare and its adverse health consequences in TM adults.

Despite its strengths, the present research has limitations. Given its cross-sectional design, this study cannot establish the causal influence of healthcare mistreatment on the development of rejection sensitivity and the healthcare avoidance behaviors of TM adults. Further, although lifetime mistreatment in healthcare likely preceded transphobia-related rejection sensitivity among TM adults in healthcare contexts, which potentially proceeded past 12-month healthcare avoidance, only a longitudinal approach can establish the temporal sequence required to fully establish mediation. Additionally, given the use of self-reported data, healthcare mistreatment may be confounded with the measure of rejection sensitivity, such that those who self-report lifetime mistreatment are more acutely perceptive to rejection and thus more likely to perceive mistreatment in healthcare regardless of the level of rejection that occurred. Further, the study assessed healthcare mistreatment using two items of lifetime mistreatment: care refusal and provider education as a means of receiving appropriate care. While the present study did not directly assess whether participants considered having to educate their provider to be a form of mistreatment, prior research finds that having to educate one’s provider about transgender people in order to receive appropriate care is a stressor that elicits frustration, anger, and resentment for many transgender patients (Lurie, 2005; Poteat et al., 2013; Snelgrove et al., 2012). Further, these measures have been used as indicators of discrimination in national studies (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016). Still, future research should aim to more comprehensively assess mistreatment in healthcare settings [e.g., by type (verbal harassment, healthcare refusal, physical assault), frequency (never, often, all the time), timing of discriminatory events (lifetime, 3 months, 6 months)] to determine if rejection sensitivity varies according to the measurement of mistreatment.

The present study found a strong positive relationship between mistreatment in healthcare and rejection sensitivity, which suggests that rejection sensitivity may develop in response to mistreatment; however, there was variability in reported levels of rejection sensitivity. While individual differences in rejection sensitivity might be determined by heritable traits (e.g., Gunderson & Lyons-Ruth, 2008; Jang, Livesley, Vernon, & Jackson, 1996), environmental determinants (London et al., 2007), such as varying levels of exposure to both rejection and social support, may also have contributed to this variation. To that end, prior research among gay and bisexual men finds that parental acceptance, peer acceptance, and gender conformity is associated with lower levels of rejection (Pachankis et al., 2008; Pachankis, Rendina, et al., 2015). In order to further validate this model as well as explore alternative mechanisms driving rejection sensitivity in healthcare contexts for transgender adults, future longitudinal research is needed that accounts for the multiple forms of healthcare mistreatment as well as the protective factors (e.g., gender-affirming staff) that transgender adults may experience in healthcare settings. Finally, rejection sensitivity did not differ by age, race, gender identity, or income. These findings suggest the invariance of rejection sensitivity for our sample of largely young, White, Boston-area trans masculine sample. The limited diversity of the sample with regard to age, race, gender identity, and geographic location also suggest that the findings may not be generalizable to other populations, including transgender women or samples comprised largely of people of color. These limitations, therefore, warrant the testing of the rejection sensitivity model measure in larger, geographically and ethnically diverse TM samples as well as with transgender women to determine if psychological responses to stigma and behavioral avoidance of mistreatment occur similarly in these populations.

Conclusion

In sum, the present study proposed and tested a social learning model to explain how TM adults experience rejection and may come to avoid health-promoting resources. The study yielded a valid and reliable measure of rejection sensitivity that is useful for understanding how TM adults identify and interpret potentially discriminatory events in healthcare settings. Extending the growing body of research on healthcare discrimination and avoidance among TM adults (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016; Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015; White Hughto et al., 2016), this study demonstrated that rejection sensitivity mediates the association between experiences of mistreatment and avoidance of necessary care. Given that healthcare avoidance is associated with poor health outcomes in transgender adults (Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Reisner, Hughto, et al., 2015; Reisner, Pardo, et al., 2015), this study further establishes stigma as a fundamental cause of poor health in this population (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013; Link & Phelan, 1995; White Hughto et al., 2015) and highlights the need for multilevel interventions to target individual (e.g., sensitivity to mistreatment in healthcare, healthcare avoidance), interpersonal (i.e., bias or uninformed clinical encounters), and structural (e.g., restrictive healthcare policies) forms of stigma in order to improve healthcare access and ultimately the health of TM people.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE.

This study creates a new measure of transphobia-related rejection sensitivity among transgender people and demonstrates that heightened vigilance and perception of rejection might drive healthcare avoidance in this population. Clinical suggestions are offered for reducing this heightened sensitivity among transgender individuals who have been mistreated.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Acknowledgements: This research was partly supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) #CER-1403-12625 awarded to Dr. Sari Reisner. Jaclyn White Hughto was also funded with support from the National Institute on Minority Health Disparities (1F31MD011203-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

References

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein IM, McDowell M, Alizaga NM, Reisner SL, Potter J. Perceptions of cervical cancer risk and screening among transmasculine individuals: Patient and provider perspectives. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2016;18(10):1–15. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1177203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist. 2015;70(9):832–864. doi: 10.1037/a0039906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber TE, Werner PD. The relationship between anxiety and sexual functioning in lesbians and heterosexual women. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56(5):639–654. doi: 10.1080/00918360903005303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the U.S. transgender population. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, Wong S, Geiger E, Soderstrom B. Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2(3):253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral RR, Smith TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(4):537–554. doi: 10.1037/a0025266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Cohen LR, Scarvalone P. Understanding revictimization among childhood sexual abuse survivors: An interpersonal schema approach. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;16(1):91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, Meyer WJ. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2012;13(4):165–232. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The Brief symptom inventory-18 (BSI-18): Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(2):545–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Olsen EOM, Brener ND, Scanlon KS, Kim SA, Demissie Z, Yaroch AL. A comparison of fruit and vegetable intake estimates from three survey question sets to estimates from 24-hour dietary recall interviews. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013;113(9):1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6(1):231–247. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaskerud JH. Matching client and therapist ethnicity, language, and gender: A review of research. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1990;11(4):321–336. doi: 10.3109/01612849009006520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Reisner SL, Laurenceau JP, Nemoto T, Operario D. Gender minority stress, mental heath, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgener women and their cisgender male partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(4):437–447. doi: 10.1037/a0037171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Reisner SL, Parsons JT, Golub SA. Association between socioeconomic position discrimination and psychological distress: Findngs from a community-based sample of gay and bisexual men in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(11):2094–2101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliem JA, Gliem RR. Proceedings from the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education. Columbus, OH: 2003. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AR, Meyer IH. Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against LGB individuals. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2008;3(3):55–71. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis LA, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 2011 Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf.

- Hash K, Rogers A. Clinical practice with older LGBT clients: Overcoming lifelong stigma through strength and resilience. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;41(3):249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.ustranssurvey.org/report/

- Jang KL, Livesley W, Vernon P, Jackson D. Heritability of personality disorder traits: A twin study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1996;94(6):438–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:80–94. (Extra Issue) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, Paltin I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(3):481–506. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie S. Identifying training needs of health-care providers related to treatment and care of transgendered patients: A qualitative needs assessment conducted in New England. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2005;8(2–3):93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Luterek JA, Harb GC, Heimberg RG, Marx BP. Interpersonal rejection sensitivity in childhood sexual abuse survivors: Mediator of depressive symptoms and anger suppression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(1):90–107. doi: 10.1177/0886260503259052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(4):896–918. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, Mueser KT. Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(2):146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR, Ramrattan ME. Extension of the rejection sensitivity construct to the interpersonal functioning of gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):306–317. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, Parsons JT. LGB-affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(5):875–889. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. A minority stress—emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology. 2015;34(8):829–840. doi: 10.1037/hea0000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;84:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Peitzmeier SM, White Hughto JM, Cavanaugh T, Pardee DJ, Potter J. Comparing self- and provider-collected swabbing for HPV DNA testing in female-to-male transgender adult patients: a mixed-methods biobehavioral study protocol. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2017;17(1):444–454. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Gamarel KE, Nemoto T, Operario D. Dyadic effects of gender minority stressors in substance use behaviors among transgender women and their non-transgender male partners. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(1):63–71. doi: 10.1037/0000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Hughto JM, Dunham EE, Heflin KJ, Begenyi JB, Coffey-Esquivel J, Cahill S. Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Quarterly. 2015;93(3):484–515. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Gamarel KE, White Hughto JM, Pardee DJ, Keo-Meier CL. Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among U.S. female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):324–332. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Randazzo RK, Hughto JMW, Peitzmeier S, DuBois LZ, Pardee DJ, Potter J. Sensitive health topics with underserved patient populations: Methodological considerations for online focus group discussions. Qualitative Health Research, Ahead of print. 2017:1–16. doi: 10.1177/1049732317705355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter TR, Newcomb ME, Whitton SW, Mustanski B. Intimate partner violence victimization in LGBT young adults: Demographic differences and associations with health behaviors. Psychology of Violence. 2017;7(1):101–109. doi: 10.1037/vio0000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CB, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino RR. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarvalone P, Fox M, Safran JD. Interpersonal Schemas: Clinical Theory, Research, and Implications. In: Baldwin MW, editor. Interpersonal Cognition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 359–387. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online. 2003;8(2):23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Ranby KW, Meade CS, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Kochman A. Reductions in traumatic stress following a coping intervention were mediated by decreases in avoidant coping for people living with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(2):274. doi: 10.1037/a0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelgrove J, Jasudavisius A, Rowe B, Head E, Bauer G. “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12(1):110–113. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Payton G, Golub SA, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Contextualizing condom use: Intimacy interference, stigma, and unprotected sex. Journal of Health Psychology. 2014;19(6):711–720. doi: 10.1177/1359105313478643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston R, Gore PA. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–751. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Clark KA, Altice FL, Reisner SL, Kershaw TS, Pachankis JE. Improving correctional healthcare providers’ ability to care for transgender patients: Development and evaluation of a theory-driven cultural and clinical competence intervention. Social Science and Medicine. 2017;195:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Murchison G, Clark K, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Geographic and individual differences in healthcare access for U.S. transgender adults: A multilevel analysis. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):424–433. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Pachankis JE, Willie TC, Reisner SL. Victimization and depressive symptomology in transgender adults: The mediating role of avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2017;64(1):41–51. doi: 10.1037/cou0000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Rose AJ, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Barriers to gender transition-related healthcare: Identifying underserved transgender adults in Massachusetts. Transgender Health. 2017;2(1):107–118. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and hental Health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]