Abstract

PURPOSE: Prognostic schemes that rely on clinical variables to predict outcome after resection of colorectal metastases remain imperfect. We hypothesized that molecular markers can improve the accuracy of prognostic schemes. METHODS: We screened the transcriptome of matched colorectal liver metastases (CRCLM) and primary tumors from 42 patients with unresected CRCLM to identify differentially expressed genes. Among the differentially expressed genes identified, we looked for associations between expression and time to disease progression or overall survival. To validate such associations, mRNA levels of the candidate genes were assayed by qRT-PCR from CRCLM in 56 additional patients who underwent hepatectomy. RESULTS: Seven candidate genes were selected for validation based on their differential expression between metastases and primary tumors and a correlation between expression and surgical outcome: lumican; tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 1; basic helix-loop-helix domain containing class B2; fibronectin; transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1; mitogen inducible gene 6 (MIG-6); and serpine 2. In the hepatectomy group, only MIG-6 expression was predictive of poor survival after hepatectomy. Quantitative PCR of MIG-6 mRNA was performed on 25 additional hepatectomy patients to determine if MIG-6 expression could substratify patients beyond the clinical risk score. Patients within defined clinical risk score categories were effectively substratified into distinct groups by relative MIG-6 expression. CONCLUSIONS: MIG-6 expression is inversely associated with survival after hepatectomy and may be used to improve traditional prognostic schemes that rely on clinicopathologic data such as the Clinical Risk Score.

Introduction

Hepatic resection combined with chemotherapy is the standard treatment for patients with hepatic colorectal cancer metastases (CRCLM) and can lead to a 5-year survival of 30% to 58% [1], [2]. The improved survival compared to chemotherapy alone, where patients rarely survive beyond 5 years, is ascribed to improvements in operative techniques, perioperative management, better imaging, and more effective chemotherapy. Two first-line therapies, 5-fluorouracil-leucovorin-oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil-leucovorin-irinotecan, are approved for advanced-stage CRCLM [3], [4]. However, substantial heterogeneity remains in outcomes for patients undergoing resection of CRCLM.

As surgeons become increasingly aggressive in resecting CRCLM, frequently accepting patients over 80 years old and with more extensive comorbidities, it becomes increasingly important to use prudent patient selection criteria based on biologic determinants of outcome. Thus, scoring systems have been developed with the goal of stratifying patients considered for liver resection into risk groups. Such prognostic schemes utilize clinicopathologic variables to estimate the risk of recurrence and death after hepatectomy for CRCLM [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Patients with a low risk of recurrence after hepatectomy may not benefit from neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy and may avoid the toxicity of perioperative chemotherapy [10]. However, when the risk of recurrence is high or the chance of complete resection is in question, delayed hepatectomy after a period of neoadjuvant therapy should be considered [11]. A neoadjuvant treatment course provides time to determine whether additional disease is present, allows assessment of tumor response to chemotherapy, and may facilitate complete tumor resection in patients with extensive hepatic metastases [12]. The potential benefits of delayed resection should be weighed against the risk of preoperative hepatotoxicity, disease progression, and the higher complication rates associated with hepatectomy after neoadjuvant therapies [13]. Although no clinical feature should absolutely exclude a patient from potentially curative hepatectomy, nonoperative management should be considered in those with an exceedingly high risk of recurrence and poor performance status.

The Clinical Risk Score (CRS) is a prognostic scheme composed of five preoperative variables: tumor number; largest tumor diameter; lymph node status during resection of the primary tumor; disease-free interval; and serum carcinoembryonic antigen level [5]. These are factors prognostic for clinical outcome and are generally available in the preoperative evaluation of patients. The CRS ranges from 0 to 5, depending on the number of unfavorable characteristics present. Each variable in the CRS is equally weighted with a single point for each unfavorable characteristic. Ideal candidates for hepatectomy have solitary metastases with a diameter less than 5 cm, serum CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) <200 ng/ml, metachronous disease, and negative regional lymph nodes found at resection of the primary tumor (i.e., CRS = 0). However, even the most favorable CRS of 0 is associated with a 5-year actuarial survival rate of only 60%. Thus, patients within the lowest CRS category are still at risk of recurrence and death.

Although the CRS is a validated prognostic system, it remains imperfect [14]. One investigation of long-term outcomes after hepatectomy found that patients with a CRS of 0-2 had a 10-year actuarial survival rate twice as high as patients with a CRS of 3-5 (21% versus 10%) [15]. However, no preoperative clinical feature or CRS precluded a curative outcome in that study. One other study that attempted external validation of three prognostic schemes for CRCLM, including the CRS, failed to confirm any predictive utility in a cohort of 662 patients [16]. Recently, Dupre et al. reported that scoring systems by themselves are of limited value for stratifying patients operated on for recurrent colorectal liver metastases [17]. We have sought to improve prognostic schemes in order to better guide clinicians in the application of individualized treatment plans and to determine the best therapeutic course for their patients.

The molecular heterogeneity of colorectal cancer leads to large variations in the response of individual patients to therapy [18]. Microsatellite instability and a small group of molecular markers, including the mutational status of the BRAF and KRAS genes, are used for treatment decisions and patient stratification. However, groups of patients defined by these molecular markers still differ significantly in their responses to therapy. In recent years, several approaches to further subtype CRC have come into use, and among the most powerful of these is gene expression profiling, which can improve on the limitations of single gene testing. Gene expression profiling has defined subtypes of colorectal cancers that are predictive or prognostic of patient responses to therapies. [18]

In the present study, we sought to find prognostic markers for CRCLM and to determine if such markers could improve the accuracy of the CRS. We used microarrays to compare the transcriptome in CRCLM versus their primary tumors. From a group of genes with differential expression between CRCLM and their primary tumors, we selected a subgroup of genes with expression levels that associated with survival or time to disease progression. We validated the findings by quantitative PCR of mRNA from additional patients and found one gene, mitogen inducible factor-6 (MIG-6), which was predictive of poor survival. Lastly, we tested whether MIG-6 expression could substratify patients within defined CRS categories. Our results show that molecular subtypes can complement clinical risk stratification to distinguish lower- from higher-risk patients with CRCLM.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Retrieval and RNA Extraction

All institutional review board requirements for human studies were met, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. All tissues were obtained at the time of surgery. All tissues were obtained at the time of surgery. Resected or Tru-cut needle biopsied (superficial) liver metastases (0.5-1.0 g) were snap frozen in the operating room within 2 minutes of harvest by transfer to a Dewar flask containing liquid nitrogen, transported to the laboratory, and stored at −80°C. Similarly, samples of resected primary colon or rectal tumors were taken in the operating room under the observation of a pathologist to preserve surgical and pathological margins and then snap frozen.

Matched samples of primary colon tumor (T); normal colon (N); and, in all but 6 cases, metastatic tumors of the liver (M) were obtained from each of 42 patients treated at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. Laser capture microdissection was performed on frozen tissue sections to separate normal and cancerous epithelial cells from surrounding stromal elements.

RNA Extraction

RNA was extracted from tissue lysates using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and amplified using an in vitro transcription-mediated procedure that maintains relative abundances of mRNAs [19]. Each sample was separately labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescent dyes. Prior to labeling, nonhuman RNA transcripts corresponding to control clones on microarrays were spiked into each sample in known amounts. The amounts of the spiked control transcripts were varied between the Cy3- and Cy5-labelings to create known differentials in the levels of some of these genes. Cy3- or Cy5-labeled nucleotides were incorporated during first-strand cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription using SuperScript II (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), primed with (dT)25 and random nonamers (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ). Following RNase digestion, the labeled probe was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA).

cDNA Microarray Assays

DNA microarray analysis was performed as described [20]. mRNA expression was measured using two-color microarrays containing different sets of cDNA clones. The dsDNA clones were produced by PCR using primers complementary to the vector sequences flanking the cDNA inserts. Each slide included approximately 384 human “housekeeping” genes and non-human (e.g. Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster, plasmid, etc.) clones for quality control. PCR products were assessed for purity and yield by agarose-gel electrophoresis and were sequenced to verify their identities. Clones found to contain Alu repetitive elements were excluded from further analysis. A total of 36,518 clones that passed the quality criteria were assigned to 1 of 17,708 unique transcripts by GenBank accession number, representing 10,671 unique genes by LocusLink ID. Of these, 6501 genes were measured by at least 2 clones, usually with different sequences. After hybridization and washing, slides were scanned with a Generation III scanner (Molecular Dynamics). Relative gene expression was measured between pairs of co-hybridized samples. Depending on what samples were available from each patient, three comparisons of expression levels were made: metastatic tumor vs. primary tumor (M/T), primary tumor vs. normal epithelium (T/N), and metastatic tumor vs. normal epithelium (M/N). In each comparison, the pair of samples was measured twice with reverse labeling to eliminate bias introduced by the fluorescence properties of the different dyes. For 32 of the patients, T/N, M/N and M/T expression were all measured.

Microarray Data Analysis

Microarray image analysis was performed using ImaGene software (BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA). For each spot, the median pixel intensity and standard deviation were determined, as well as the spot area, signal area, and local background intensity. For each cDNA clone, the results from four spots (two duplicates per slide, Cy3 and Cy5 labeled) were averaged, and a standard deviation was calculated. A clone was detected if its signal was at least 5 standard deviations above background. A ratio of expression between the two samples and its uncertainty were calculated from the intensities. Each array was normalized such that the median ratio observed among the clones measuring genes spiked into the Cy3 and Cy5 samples in equal amounts was one. A global normalization was then applied such that the median ratio observed across all of the cDNA spots on all of the arrays for each sample was 1. For each ratio, a significance call was assigned: undetected (in both the numerator and denominator), on (detected in the numerator only), off (detected in the denominator only), up or down (significantly over-expressed in the numerator or denominator, respectively), or equal (detected, but ratio not significantly different from one). To be called significantly up- (down-) regulated, a gene’s expression must not only be greater (less) than the cut, but it had to be greater (less) than 1 with at least 95% certainty based on the uncertainty in the log ratio.

For the 32 patients that had T/N, M/N, and M/T expression measurements, consistency was required between the results of the three measurements for each spot, such that 4/5 < (T/N)*(M/T)/(M/N) < 5/4, i.e., the three ratios should cancel to give a value of 1 within 25%. A list of genes that were differently expressed by more than 1.5-fold between the metastatic and primary tumors of these patients was generated. The number of ratios deemed sufficiently well measured to use (detected; consistent between T/N, M/N, and M/T measurements) varied for different spots. At least 10 good measurements were required for each spot to be considered. A total of 22,344 of 36,518 spots, assigned to 8027 of the 10,671 unique genes on the arrays, passed this criterion. Maximum likelihood estimates of the upper and lower 99% confidence limits on the prevalence in the parent population were calculated for each spot on the basis of the number of ratios exceeding the cut out of the number of good ratios. Spots judged to be up- or downregulated in 20% of the parent population with 99% certainty were included in the list. Thus, if only 10 good ratios were measured for a particular spot, 7 would have to make the cut (70%); if there were 32 good ratios, 14 would suffice (43%). When more than one spot assigned to a particular gene met these criteria, their average expression ratio in each patient was calculated, weighted by the inverse uncertainty squared for each ratio.

RT and qRT-PCR

cDNAs were synthesized from 2 μg total RNA using a SuperScript III first-strand synthesis kit. One microliter of the first cDNA synthesis mix was dispensed in triplicate and mixed with Taqman Universal PCR Mastermix and Taqman Gene Expression Assays in an end-volume of 10 μl into optical 384-well plates for Taqman RT-PCR. PCR primers for MIG-6 [Hs00219060_m1], fibronectin 1 (HS00415006_m1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 [Hs00171558_m1], serine proteinase inhibitor member 2 [Hs00299953_m1], lumican [Hs00158940_m1], basic helix-loop-helix domain containing class B2 [Hs00186419], transmembrane 4 superfamily member-1 [Hs00371997], and the TaqMan probe were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Actin-B [Hs99999903_m1] was chosen as an endogenous normalization control. The Applied Biosystems ABI Prism 7900 was used for qRT-PCR. Samples were incubated at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. In nontemplate control replicates of each gene, no false positives were detected, and all the assays were done in triplicate. Quantitative RT-PCR triplicate runs were repeated on a separate day to confirm reproducibility.

Statistical Analysis

We screened the transcriptome for associations between candidate gene expression and outcomes using linear regression analysis. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-square tests. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival curve estimates were compared by the log-rank test. Cox proportional-hazards regression was performed on independent variables that were added sequentially in a stepwise fashion such that they were entered if P < .05 and removed if P > .10. Statistical calculations were done with MedCalc Version 7.0.1.0 software (Mariakerke, Belgium). Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Where applicable, the cutoff point for stratifying gene expression groups was determined using the Maxstat statistical package in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Version 2.0.0, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-00-3, URL: http://cran.r-project.org/).

Results

Candidate Genes Selected from the Screening Microarray

Using a cDNA-based microarray that included 35,518 spots representing 10,671 unique genes, we screened the transcriptome for genes that were differentially expressed in unresected metastases of colorectal cancer relative to their primary tumors in 42 patients. The characteristics of these patients were: median age 59 years (range 31-82); 61% male, 29% female; primary tumor site 43% right colon, 33% left colon, 2% right and left colon, 22% rectum; primary node status 15% positive, 85% negative; time to progression 91% </= 12 months (synchronous) and 9% >12 months (metachronous); the median number of hepatic metastases was 3 with a range of 1-11; and the average CEA was 141.

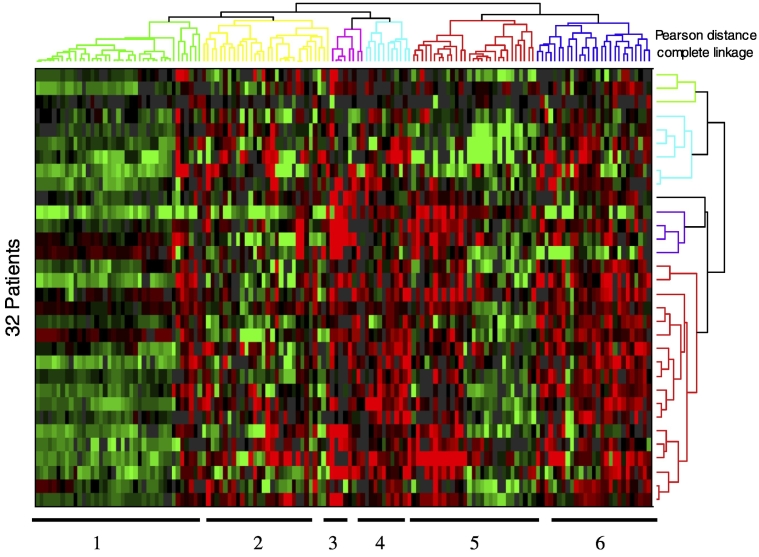

In the screen, 22,344 spots representing 8,027 unique genes met criteria for analysis. From the 10,671 genes in the microarray, 144 demonstrated differential expression between primary colon tumors and matched hepatic metastases. Differential expression was defined as at least 1.5-fold difference in at least 20% of matched primary and metastatic samples. Transcripts showing a tendency for increased expression in the metastases relative to primary tumors are in Table 1, while those exhibiting decreased expression are in Table 2. Hierarchical clustering applying the Pearson correlation for the distance metric and complete linkage identified six distinct spot clusters, which are shown in the heat map of differentially expressed genes (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sixty-Eight Genes with Increased mRNA Expression in Hepatic Metastases Relative to Primary Colon Tumors from the Same Patient

| Locus ID | Symbol | Gene | Spots | N | >1.5× | >2× | >4× | >10× | ON | CLUST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8991 | SELENBP1 | selenium binding protein 1 | 1 | 30 | 56.7% | 43.3% | 23.3% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 163732 | CITED4 | Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 4 | 1 | 26 | 53.8% | 38.5% | 23.1% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 4060 | LUM | lumican | 4 | 32 | 62.5% | 43.8% | 15.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 5266 | PI3 | protease inhibitor 3, skin-derived (SKALP) | 1 | 26 | 53.8% | 50.0% | 11.5% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 27290 | SPINK4 | serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 4 | 1 | 21 | 52.4% | 28.6% | 28.6% | 9.5% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 27248 | XTP3TPB | XTP3-transactivated protein B | 1 | 26 | 50.0% | 34.6% | 19.2% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 9518 | GDF15 | growth differentiation factor 15 | 2 | 31 | 51.6% | 38.7% | 16.1% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 374354 | FLJ25621 | FLJ25621 protein | 1 | 23 | 52.2% | 34.8% | 17.4% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 2192 | FBLN1 | fibulin 1 | 2 | 15 | 53.3% | 46.7% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 11167 | FSTL1 | follistatin-like 1 | 2 | 31 | 61.3% | 41.9% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 4313 | MMP2 | matrix metalloproteinase 2 (gelatinase A, 72kDa gelatinase, 72kDa type IV collagenase) | 2 | 26 | 65.4% | 34.6% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 2049 | EPHB3 | EphB3 | 1 | 27 | 48.1% | 33.3% | 18.5% | 3.7% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 800 | CALD1 | caldesmon 1 | 1 | 28 | 50.0% | 39.3% | 10.7% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 57535 | KIAA1324 | maba1 | 1 | 27 | 51.9% | 33.3% | 7.4% | 3.7% | 3.7% | 3 |

| 4535 | MTND1 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 | 2 | 30 | 63.3% | 36.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 1634 | DCN | decorin | 6 | 32 | 53.1% | 28.1% | 15.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 26073 | POLDIP2 | polymerase (DNA-directed), delta interacting protein 2 | 1 | 27 | 51.9% | 29.6% | 14.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 26047 | CNTNAP2 | contactin associated protein-like 2 | 1 | 21 | 52.4% | 28.6% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 9.5% | 4 |

| 1513 | CTSK | cathepsin K (pycnodysostosis) | 1 | 15 | 53.3% | 33.3% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 131177 | FAM3D | family with sequence similarity 3, member D | 1 | 29 | 48.3% | 24.1% | 13.8% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 5786 | PTPRA | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, A | 1 | 29 | 58.6% | 34.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 5327 | PLAT | plasminogen activator, tissue | 2 | 28 | 60.7% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 10406 | WFDC2 | WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 | 1 | 25 | 52.0% | 24.0% | 12.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 1278 | COL1A2 | collagen, type I, alpha 2 | 2 | 32 | 43.8% | 31.3% | 9.4% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 132160 | FLJ32332 | likely ortholog of mouse protein phosphatase 2C eta | 1 | 31 | 48.4% | 32.3% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 4536 | MTND2 | NADH dehydrogenase 2 | 2 | 31 | 54.8% | 29.0% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 7433 | VIPR1 | vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 | 1 | 21 | 57.1% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 4091 | MADH6 | MAD, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 6 (Drosophila) | 1 | 28 | 60.7% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 1277 | COL1A1 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 1 | 20 | 50.0% | 30.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 1504 | CTRB1 | chymotrypsinogen B1 | 1 | 30 | 53.3% | 26.7% | 3.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 6741 | SSB | Sjogren syndrome antigen B (autoantigen La) | 1 | 27 | 55.6% | 25.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 27122 | DKK3 | dickkopf homolog 3 (Xenopus laevis) | 1 | 20 | 50.0% | 25.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 23469 | PHF3 | PHD finger protein 3 | 1 | 30 | 60.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 5908 | RAP1B | RAP1B, member of RAS oncogene family | 1 | 30 | 53.3% | 26.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 5295 | PIK3R1 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit, polypeptide 1 (p85 alpha) | 1 | 25 | 52.0% | 24.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 3297 | HSF1 | heat shock transcription factor 1 | 1 | 30 | 56.7% | 23.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 2 | A2M | alpha-2-macroglobulin | 1 | 30 | 46.7% | 26.7% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 81558 | LOC81558 | C/EBP-induced protein | 1 | 29 | 51.7% | 24.1% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 5801 | PTPRR | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, R | 1 | 29 | 44.8% | 31.0% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 2487 | FRZB | frizzled-related protein | 1 | 18 | 55.6% | 16.7% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 6348 | CCL3 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | 1 | 27 | 51.9% | 22.2% | 3.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 2006 | ELN | elastin (supravalvular aortic stenosis, Williams-Beuren syndrome) | 1 | 27 | 48.1% | 29.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 84859 | MGC4126 | hypothetical protein MGC4126 | 2 | 31 | 45.2% | 25.8% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 4513 | MTCO2 | cytochrome c oxidase II | 3 | 31 | 51.6% | 22.6% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 146880 | MGC40489 | hypothetical protein MGC40489 | 1 | 30 | 46.7% | 26.7% | 3.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 83483 | PLVAP | plasmalemma vesicle associated protein | 1 | 25 | 48.0% | 28.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 6678 | SPARC | secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin) | 1 | 29 | 44.8% | 24.1% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 132241 | LOC132241 | hypothetical protein LOC132241 | 1 | 29 | 51.7% | 20.7% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 67122 | Nrarp | Notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 28.6% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 398 | ARHGDIG | Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) gamma | 1 | 27 | 44.4% | 18.5% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 51599 | LISCH7 | liver-specific bHLH-Zip transcription factor | 1 | 30 | 50.0% | 23.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 81788 | SNARK | likely ortholog of rat SNF1/AMP-activated protein kinase | 1 | 29 | 51.7% | 20.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 57605 | PITPNM2 | phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, membrane-associated 2 | 1 | 29 | 51.7% | 20.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 51332 | SPTBN5 | spectrin, beta, non-erythrocytic 5 | 1 | 25 | 48.0% | 20.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 4541 | MTND6 | NADH dehydrogenase 6 | 6 | 32 | 43.8% | 25.0% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 56940 | DUSP22 | dual specificity phosphatase 22 | 1 | 27 | 48.1% | 22.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 2580 | GAK | cyclin G associated kinase | 1 | 27 | 51.9% | 18.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 23432 | GPR161 | G protein-coupled receptor 161 | 1 | 29 | 48.3% | 20.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 583 | BBS2 | Bardet-Biedl syndrome 2 | 1 | 29 | 48.3% | 20.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 2045 | EPHA7 | EphA7 | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 21.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 3189 | HNRPH3 | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3 (2H9) | 1 | 31 | 48.4% | 19.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 1158 | CKM | creatine kinase, muscle | 1 | 30 | 46.7% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 9775 | DDX48 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 48 | 1 | 24 | 45.8% | 20.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 10551 | AGR2 | anterior gradient 2 homolog (Xenopus laevis) | 2 | 29 | 41.4% | 24.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 1999 | ELF3 | E74-like factor 3 (ets domain transcription factor, epithelial-specific ) | 1 | 30 | 43.3% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 27336 | HTATSF1 | HIV TAT specific factor 1 | 1 | 29 | 44.8% | 17.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 7125 | TNNC2 | troponin C2, fast | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 3040 | HBA2 | hemoglobin, alpha 2 | 1 | 27 | 48.1% | 3.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

Each gene is identified by its LocusLink ID, symbol, and name. The “Spots” column indicates the number of spots (cDNA clones) used to measure each gene’s expression. The “N” column shows the maximum number of patient samples where a particular gene was measured; this number was used in calculating the average percent prevalence across patients. The average prevalence, for cuts of 1.5-, 2-, 4-, and 10- fold increased M/T expression, or cases where the gene was only detected in the metastatic tumor sample (“ON”), is shown as a percentage of the patients where the gene was measured. The “CLUST” column indicates which of the clusters shown in Figure 1 each gene belongs to. The genes are ordered by the sum of the prevalence values, in decreasing order.

Table 2.

Seventy-Six Genes with Decreased mRNA Expression in Hepatic Metastases Relative to Primary Colon Tumors from the Same Patient

| Locus ID | Symbol | Gene | Spots | N | >1.5× | >2× | >4× | >10× | OFF | CLUST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | SERPINA3 | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 3 | 2 | 25 | 64.0% | 60.0% | 48.0% | 24.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 51761 | ATP8A2 | ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter-like, Class I, type 8A, member 2 | 1 | 15 | 60.0% | 53.3% | 40.0% | 26.7% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 51129 | ANGPTL4 | angiopoietin-like 4 | 1 | 18 | 66.7% | 61.1% | 22.2% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 348 | APOE | apolipoprotein E | 2 | 32 | 59.4% | 50.0% | 31.3% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 5004 | ORM1 | orosomucoid 1 | 1 | 19 | 57.9% | 42.1% | 26.3% | 15.8% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 3240 | HP | haptoglobin | 7 | 29 | 51.7% | 41.4% | 27.6% | 17.2% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 6347 | CCL2 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | 2 | 21 | 71.4% | 42.9% | 14.3% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 27295 | PDLIM3 | PDZ and LIM domain 3 | 1 | 14 | 64.3% | 50.0% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 7.1% | 5 |

| 213 | ALB | albumin | 1 | 14 | 50.0% | 35.7% | 21.4% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 7076 | TIMP1 | tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (erythroid potentiating activity, collagenase inhibitor) | 3 | 31 | 67.7% | 41.9% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 2335 | FN1 | fibronectin 1 | 4 | 32 | 56.3% | 40.6% | 18.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 710 | SERPING1 | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade G (C1 inhibitor), member 1, (angioedema, hereditary) | 1 | 26 | 50.0% | 34.6% | 26.9% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 8553 | BHLHB2 | basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B, 2 | 1 | 26 | 57.7% | 53.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 3303 | HSPA1A | heat shock 70kDa protein 1A | 4 | 31 | 48.4% | 35.5% | 22.6% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 6373 | CXCL11 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | 1 | 11 | 63.6% | 18.2% | 9.1% | 0.0% | 18.2% | 5 |

| 56937 | TMEPAI | transmembrane, prostate androgen induced RNA | 1 | 25 | 48.0% | 40.0% | 16.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 6035 | RNASE1 | ribonuclease, RNase A family, 1 (pancreatic) | 1 | 29 | 55.2% | 31.0% | 13.8% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 2316 | FLNA | filamin A, alpha (actin binding protein 280) | 2 | 31 | 51.6% | 41.9% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 768 | CA9 | carbonic anhydrase IX | 1 | 18 | 44.4% | 33.3% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 6 |

| 2885 | GRB2 | growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 | 1 | 21 | 57.1% | 33.3% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 7564 | ZNF16 | zinc finger protein 16 (KOX 9) | 1 | 27 | 51.9% | 44.4% | 7.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 4070 | TACSTD2 | tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 | 1 | 28 | 50.0% | 28.6% | 17.9% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 7052 | TGM2 | transglutaminase 2 (C polypeptide, protein-glutamine-gamma-glutamyltransferase) | 1 | 28 | 57.1% | 32.1% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 4071 | TM4SF1 | transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 | 1 | 29 | 51.7% | 41.4% | 6.9% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 10397 | NDRG1 | N-myc downstream regulated gene 1 | 1 | 30 | 56.7% | 40.0% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 2207 | FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE, high affinity I, receptor for; gamma polypeptide | 1 | 21 | 61.9% | 33.3% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 1152 | CKB | creatine kinase, brain | 3 | 32 | 50.0% | 31.3% | 12.5% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 1514 | CTSL | cathepsin L | 4 | 31 | 54.8% | 29.0% | 9.7% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 652 | BMP4 | bone morphogenetic protein 4 | 1 | 24 | 50.0% | 37.5% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 633 | BGN | biglycan | 1 | 24 | 58.3% | 37.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 3936 | LCP1 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 (L-plastin) | 1 | 23 | 47.8% | 26.1% | 13.0% | 8.7% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 2878 | GPX3 | glutathione peroxidase 3 (plasma) | 1 | 18 | 55.6% | 33.3% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 7422 | VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor | 2 | 30 | 53.3% | 33.3% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 4256 | MGP | matrix Gla protein | 1 | 30 | 46.7% | 36.7% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 374 | AREG | amphiregulin (schwannoma-derived growth factor) | 1 | 29 | 44.8% | 27.6% | 13.8% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 7701 | ZNF142 | zinc finger protein 142 (clone pHZ-49) | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 32.1% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 51366 | DD5 | progestin induced protein | 1 | 27 | 44.4% | 37.0% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 10457 | GPNMB | glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb | 1 | 26 | 50.0% | 30.8% | 11.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 22822 | PHLDA1 | pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 1 | 1 | 24 | 50.0% | 33.3% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 10123 | ARL7 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like 7 | 3 | 32 | 46.9% | 31.3% | 6.3% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 4316 | MMP7 | matrix metalloproteinase 7 (matrilysin, uterine) | 6 | 32 | 46.9% | 31.3% | 9.4% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 3576 | IL8 | interleukin 8 | 1 | 21 | 47.6% | 33.3% | 4.8% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 5163 | PDK1 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isoenzyme 1 | 1 | 29 | 58.6% | 31.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 1649 | DDIT3 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 35.7% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 7033 | TFF3 | trefoil factor 3 (intestinal) | 1 | 27 | 44.4% | 22.2% | 14.8% | 3.7% | 3.7% | 3 |

| 4493 | MT1E | metallothionein 1E (functional) | 1 | 26 | 46.2% | 30.8% | 11.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 7481 | WNT11 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 11 | 1 | 17 | 52.9% | 23.5% | 5.9% | 0.0% | 5.9% | 4 |

| 10381 | TUBB4 | tubulin, beta, 4 | 1 | 15 | 60.0% | 26.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| 5270 | SERPINE2 | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 2 | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 32.1% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 9590 | AKAP12 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein (gravin) 12 | 1 | 20 | 50.0% | 25.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 54206 | MIG-6 | mitogen-inducible gene 6 | 1 | 31 | 45.2% | 35.5% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 11067 | C10orf10 | chromosome 10 open reading frame 10 | 1 | 24 | 62.5% | 20.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 2159 | F10 | coagulation factor X | 1 | 18 | 50.0% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 57561 | ARRDC3 | arrestin domain containing 3 | 3 | 27 | 59.3% | 22.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 4495 | MT1G | metallothionein 1G | 1 | 27 | 44.4% | 22.2% | 11.1% | 3.7% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 10628 | TXNIP | thioredoxin interacting protein | 5 | 32 | 46.9% | 31.3% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 3939 | LDHA | lactate dehydrogenase A | 2 | 32 | 53.1% | 25.0% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 6890 | TAP1 | transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) | 1 | 24 | 45.8% | 20.8% | 8.3% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 1942 | EFNA1 | ephrin-A1 | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 32.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 136 | ADORA2B | adenosine A2b receptor | 1 | 22 | 50.0% | 27.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 11145 | HRASLS3 | HRAS-like suppressor 3 | 1 | 26 | 46.2% | 30.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 84951 | CTEN | C-terminal tensin-like | 1 | 21 | 52.4% | 19.0% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 90637 | LOC90637 | hypothetical protein LOC90637 | 1 | 29 | 44.8% | 27.6% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 7045 | TGFBI | transforming growth factor, beta-induced, 68kDa | 1 | 24 | 50.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 5230 | PGK1 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 1 | 32 | 46.9% | 25.0% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 64065 | PERP | PERP, TP53 apoptosis effector | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 17.9% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 9531 | BAG3 | BCL2-associated athanogene 3 | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 25.0% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 23023 | KIAA0779 | KIAA0779 protein | 1 | 21 | 47.6% | 23.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 567 | B2M | beta-2-microglobulin | 1 | 28 | 46.4% | 17.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 2317 | FLNB | filamin B, beta (actin binding protein 278) | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 14.3% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

| 665 | BNIP3L | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3-like | 2 | 30 | 46.7% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2 |

| 7431 | VIM | vimentin | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 14.3% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 |

| 91452 | ACBD5 | acyl-Coenzyme A binding domain containing 5 | 1 | 27 | 44.4% | 14.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4 |

| 1508 | CTSB | cathepsin B | 1 | 31 | 48.4% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 55818 | JMJD1 | jumonji domain containing 1 | 1 | 28 | 42.9% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6 |

| 5763 | PTMS | parathymosin | 1 | 31 | 41.9% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3 |

The columns are the same as in Table 1, except that the prevalence columns indicate percentage of patients exhibiting downregulation and the “OFF” column indicates the percentage of patients where expression was detected in the primary tumor but not the metastasis.

Figure 1.

Expression of genes that show significant up- or downregulation in metastatic tumors of the liver relative to primary colon tumors from the same patient in 20% or more of the patient population with 99% certainty based on a sampling of 32 patients. Upregulation is indicated by shades of red, downregulation is indicated by shades of green, black indicates no change, and gray indicates ratios that failed to pass detection or consistency criteria. Tables 1 and 2 indicate which cluster each of the genes belongs to.

We found 68 genes that were consistently up-regulated and 76 that were down-regulated in CRCLM relative to matched primary tumors. From this group of 144 differentially expressed genes, 7 were selected for validation based on the association between mRNA level (using values obtained from the microarray) and clinical outcome (Table 3): lumican, a proteoglycan of the extracellular matrix reported to be overexpressed in colorectal breast, neuroendocrine, and other cancers [21]; tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases and modulator of other diverse processes in cancer cells [22]; basic helix-loop-helix domain containing B2 (BHLHB2), a transcription factor that is induced by hypoxia within tumors [23]; fibronectin, an abundant extracellular matrix protein that contributes to altered stromal remodeling during tumorigenesis [24]; TM4SF1 (transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1), a tumor-associated antigen that regulates cancer cell motility and invasion [25]; serpine2, an extracellular serine protease that is overexpressed in pancreatic, colon, and stomach cancers that may facilitate invasive processes [26]; and MIG-6, a putative tumor suppressor that negatively regulates the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases [27], [28].

Table 3.

Seven Candidate Genes Were Selected on the Basis of Differential Expression Between Colorectal Liver Metastases and Their Corresponding Primary Tumor and an Association Between mRNA Level (as Determined by the Microarray Analysis) and Clinical Outcome (P<.05)

| Candidate Gene | Name | Relative Expression in CRCLM | Clinical Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUM | Lumican | Higher | OS |

| TIMP1 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 |

Lower | TTP TS |

| BHLHB2 | Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B, 2 | Lower | OS |

| FN1 | Fibronectin | Lower | TTP |

| TM4SF1 | Transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 |

Lower | OS |

| MIG-6 | Mitogen-inducible gene 6 | Lower | TTP |

| SER2 | Serpine2 | Lower | OS TS |

OS, overall survival; TTP, time to progression of liver metastases.

Association of Candidate Genes in CRC Metastases with Clinical Outcome

To determine whether the expression of the candidate genes identified above as correlating with clinical outcome for unresectable patients with colorectal metastases confined to the liver also applied to patients undergoing potentially curative hepatectomy for CRCLM, we performed qRT-PCR of the 7 candidate genes on CRCLM from 56 additional patients. qRT-PCR allowed us to more accurately quantify the levels of each transcript than obtaining such information from an array and therefore allowed more accurate substratification of patients into MIG-6–high and MIG-6–low groups. Since we often did not have matching primary tumors for these patients, mRNA levels of the metastasis and normal tissue were compared. The baseline clinical variables and their association with overall survival of the group of 56 patients who underwent potentially curative hepatectomy are in Table 4. The median follow-up time of the surviving patients in this group was 97 months after hepatectomy (range 55-107 months).

Table 4.

Results of Univariate Association of Clinicopathologic Variables with Overall Survival

| Variable | n | Median Survival (Months) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26 | 68 | 0.63 | 0.33-1.18 | .15 |

| <60 | |||||

| ≥60 | 30 | 36 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 18 | 37 | 0.88 | 0.46-1.70 | .71 |

| Male | 38 | 32 | |||

| Date of hepatectomy | |||||

| After January 1, 2000 | 19 | 29 | 1.28 | 0.65-2.71 | .44 |

| Before January 1, 2000 | 37 | 40 | |||

| Primary tumor site | |||||

| Colon | 47 | 36 | 1.03 | 0.46-2.34 | .94 |

| Rectum | 9 | 51 | |||

| Disease-free interval | |||||

| Metachronous | 23 | 54 | 0.61 | 0.33-1.17 | .14 |

| Synchronous | 33 | 33 | |||

| Hepatic lobe involvement | |||||

| Unilobar | 40 | 36 | 1.32 | 0.66-2.58 | .44 |

| Bilobar | 16 | 36 | |||

| Primary tumor node status | |||||

| N0 | 14 | 43 | 0.84 | 0.42-1.69 | .63 |

| N1 | 41 | 36 | |||

| Preoperative CEA | |||||

| <200 ng/ml | 39 | 33 | 1.37 | 0.52-3.44 | .55 |

| ≥200 ng/ml | 6 | 65 | |||

| Diameter of largest met | |||||

| <5.0 cm | 28 | 58 | 0.50 | 0.25-0.91 | .03 |

| ≥5.0 cm | 28 | 30 | |||

| Number of metastases | |||||

| Solitary | 27 | 54 | 0.57 | 0.30-1.05 | .07 |

| Multiple | 29 | 29 | |||

| Hepatectomy EBL | |||||

| <1000 ml | 30 | 36 | 1.16 | 0.62-2.19 | .64 |

| ≥1000 ml | 25 | 33 | |||

| Hepatectomy margin | |||||

| <1.0 cm | 27 | 40 | 1.11 | 0.59-2.08 | .74 |

| ≥1.0 cm | 29 | 31 |

Preoperative CEA level was not obtained in 13 patients. Primary tumor nodal status was unknown in two patients. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; met, metastasis.

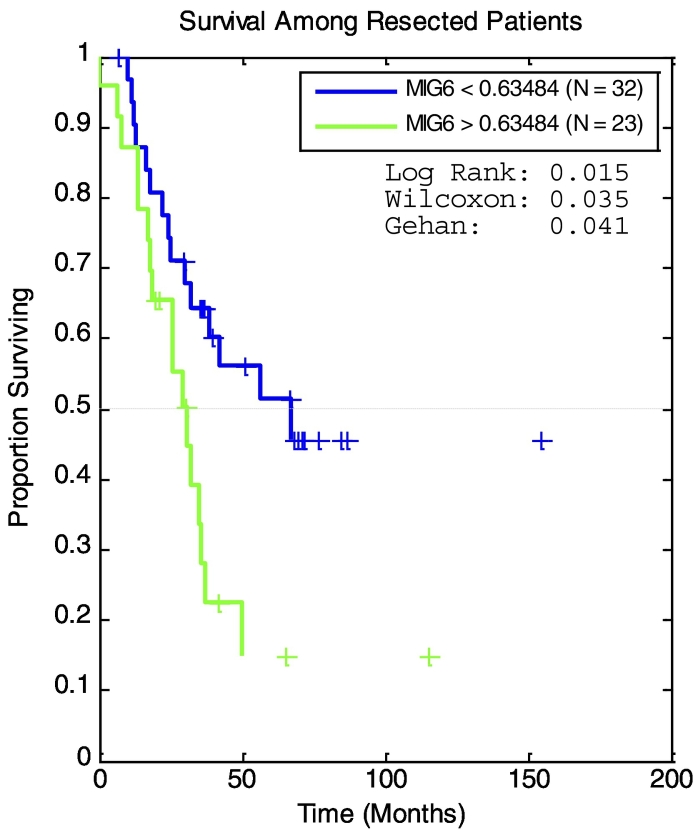

To determine if expression of any of the seven genes was associated with survival after hepatectomy, we dichotomized patients into high- and low-expression groups according to the median relative mRNA level. In this analysis, MIG-6 was the only gene whose expression was predictive of survival (Table 5). Patients in the lower 50th percentile of MIG-6 expression had a median survival that was over twice as long as that of patients in the upper 50th percentile (P = .01, Table 5). Using Maxstat software to optimize the cutoff value for high and low MIG-6 expression, a statistically significant difference in overall survival was found by Kaplan-Meier analysis (log-rank P = .0024, Figure 2). This approach also showed that none of the candidate genes, including MIG-6, was predictive of liver disease–free survival (LDFS) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis of Candidate Genes

| Candidate Gene Expression | n | Median Survival (mos) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value Survival | Median LDFS (mos) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value LDFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUM | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 50 | 0.64 | .19 | 51 | 0.55 | .10 |

| High | 27 | 32 | (0.30-1.28) | 20 | (0.24-1.14) | ||

| TIMP1 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 57 | 0.60 | .14 | 51 | 0.51 | .07 |

| High | 28 | 31 | (0.29-1.19) | 20 | (0.23-1.06) | ||

| BHLHB2 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 57 | 0.59 | .13 | NR | 0.55 | .11 |

| High | 28 | 31 | (0.28-1.17) | 27 | (0.26-1.16) | ||

| FN1 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 57 | 0.63 | .18 | 46 | 0.80 | .54 |

| High | 28 | 31 | (0.30-1.26) | 27 | (0.37-1.69) | ||

| TM4SF1 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 42 | 0.90 | .77 | 46 | 0.94 | .86 |

| High | 28 | 31 | (0.44-1.83) | 27 | (0.44-1.99) | ||

| Mig-6 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 67 | 0.42 | .01 | NR | 0.55 | .10 |

| High | 28 | 29 | (0.18-0.80) | 20 | (0.24-1.12) | ||

| SER2 | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 42 | 0.79 | .50 | 46 | 0.76 | .47 |

| High | 27 | 31 | (0.38-1.61) | 20 | (0.35-1.62) |

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on colorectal liver metastases from 56 additional patients that underwent hepatectomy. Patients above and below the median expression level were compared by log-rank testing.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of survival in patients after resection stratified by MIG-6 expression. MaxStat software was used to optimize the cutoff value for high and low MIG-6 expression. A statistically significant difference in overall survival was found by this analysis (log-rank P = .0024)

High- and Low-CRS Patients Further Stratified by MIG-6 Gene Expression

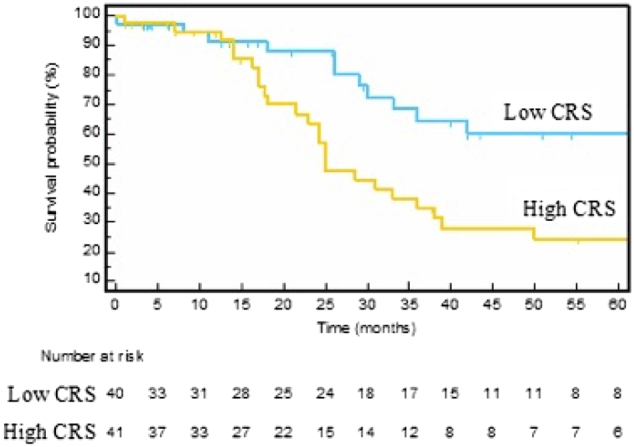

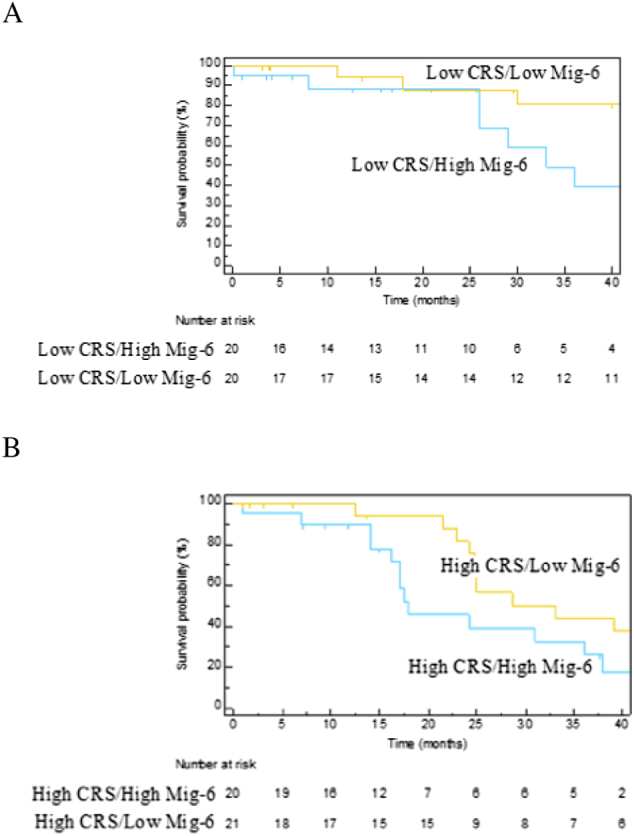

Because MIG-6 was the only gene whose expression predicted survival, we were interested in whether patients with a high or low CRS could be further stratified by MIG-6 expression. This led us to perform qRT-PCR of MIG-6 mRNA on 25 additional patients with CRCLM (total n = 81 patients). To determine if the CRS predicted survival after hepatectomy in this cohort, we generated Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of low CRS (0-2) and high CRS (3-5). Although the median survival of the low CRS group was not reached, the median survival of the high-CRS group was 25 months. The Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for the low-CRS group were higher than those for the high-CRS group (log-rank P = .005, Figure 3). Within the low-CRS group (n = 40), stratifying by median MIG-6 expression resulted in low– (n = 20) and high– (n = 20) MIG-6 expression subgroups (Figure 4A). Median survival was 33 months for patients in the subgroup with low CRS and high MIG-6 but was not reached in the subgroup with low CRS and low MIG-6. When patients in the low-CRS group were substratified by the median MIG-6 level, statistically distinct survival curves by log-rank testing (P = .03) resulted.

Figure 3.

Patient stratification for overall survival by CRS. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates comparing low-CRS (0-2) vs. high-CRS (3–5) groups. The median overall survival was 25 months in the high-CRS group, but it was not reached in the low-CRS group (P = .005). Fourteen patients did not have preoperative CEA levels and were excluded from the analysis. Numbers below the figure are life tables designating how many patients are represented in the survival curves.

Figure 4.

MIG-6 can substratify patients beyond the CRS. Patients divided into low-CRS (0-2) and high-CRS (3-5) groups were further stratified by median MIG-6 expression. (A) Within the low-CRS group, patients were separated into two groups: those in the upper 50th percentile of MIG-6 expression and those in the lower 50th percentile. The median overall survival was 33 months in the upper–MIG-6 subgroup and was not reached in the lower–MIG-6 group (P = .03). (B) Similarly, within the high-CRS group, patients were separated into two groups: those in the upper 50th percentile of MIG-6 expression and those in the lower 50th percentile. The median overall survival in the upper– and lower–MIG-6 subgroups was 18 and 33 months, respectively (P = .04). Numbers below the figure are life tables designating how many patients are represented in the survival curves.

When patients in the high-CRS group (n = 41) were stratified by median MIG-6 expression, the median survival was almost twice as long in the low–MIG-6 subgroup (n = 21) as it was in the high–MIG-6 subgroup (n =20) (Figure 4B). As with the low-CRS group, patients with a high CRS could be effectively substratified by median MIG-6 expression, resulting in statistically distinct survival curves by log-rank testing (P = .04).

Discussion

We used gene expression profiling to identify differentially expressed genes in CRCLM relative to matched primary tumors. Among the genes identified, MIG-6 (also called gene-33, RALT, or ERRFI1) encodes an adaptor protein that interacts with and inhibits the activities of members of the ErbB receptor family and other receptor tyrosine kinases [29], [30]. The human MIG-6 gene is on chromosome 1p36, a locus associated with many cancers [31], and MIG-6 is proposed to be a tumor suppressor [28], [32]. Consistent with this, MIG-6 expression is reduced in human breast, skin, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers, and diminished MIG-6 expression in patients with breast cancer correlates with poor survival [33], [34]. Furthermore, germline disruption of the murine MIG-6 gene leads to cancers of the lung, gallbladder, bile duct, skin, and gastrointestinal tract [29], [32]. Identification of MIG-6 as a gene that has low expression in CRCLM relative to matched primary cancers may suggest that MIG-6 can act as a suppressor of metastasis.

We found that elevated MIG-6 mRNA expression was associated with decreased survival after hepatectomy of CRCLM. This observation should be considered in concert with results showing that MIG-6 has diverse functions in both physiology and pathology which, depending on context, can promote survival or cell death.

MIG-6 transcription is induced by diverse stimuli including growth factors [35], [36], hormones [37], cytokines [29], [38], and hypoxia [39]. MIG-6 is a feedback inhibitor of all members of the ErbB receptor family [29], [30], with the EGFR being best investigated. Activation of the EGFR increases MIG-6 transcription in a RAS-ERK–dependent fashion [40], [41], leading to accumulation of the MIG-6 protein within 60-90 minutes. In turn, MIG-6 binds the tyrosine kinase domain of the activated EGFR, inactivates the receptor tyrosine kinase, and thereby attenuates EGFR action. Thus, MIG-6 −/− mice display epidermal hyperplasia and have an increased susceptibility to skin carcinogenesis, which is caused by unabated EGFR signaling [29]. During lung development and vascularization, the absence of MIG-6 leads to hyperplasia of several tissues, as well as to enhanced apoptosis of endothelial cells and diminished expression of angiogenic factors [42]. Considered together, the observations summarized above show that that MIG-6 may coordinate life and death decision making to facilitate tissue homeostasis [27], [28].

It has been commonly assumed that MIG-6 functions solely as a tumor suppressor and that EGFR acts in an oncogenic manner. However, several studies have established the ability of EGFR to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], while others have established the ability of MIG-6 to protect human breast cancer cells from apoptosis [42], [48]. A strong basis exists for believing that unbalanced expression of MIG-6 relative to the EGFR activates internalized EGFR, where it may initiate apoptosis [43], [44], [46], [47], [49]. Recent studies show that phosphorylation of MIG-6 may negatively affect its interaction with the EGFR as well as its capacity to induce trafficking of the EGFR [30], [50], [51]. Since the activity of MIG-6 on EGFR is dependent on its phosphorylation status, localization, and protein levels, it may be necessary to interrogate these attributes of MIG-6 in patients to know its true prognostic significance.

Petroda et al. [52] recently showed that the identification of molecular subtypes of colorectal metastases across individual patients can complement clinical risk stratification to distinguish low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients with distinct 10-year survivals. The present study builds on this approach by showing that CRCLM patients could be stratified within their respective CRS group by relative MIG-6 expression to improve prognostic accuracy for patients. Our observations should encourage evaluation of patient outcomes when MIG-6 expression and MIG-6 expression relative to EGFR localization and abundance are considered in a larger, prospective study.

This study had several limitations. The patients whose tumor specimens were used in the screening array had unresected CRCLM, whereas patients in the validation group underwent hepatectomy. Ideally, screening and validation groups have identical clinical features and undergo identical treatment. Furthermore, the samples utilized were not randomly selected but rather represented patients who had tissue available for research. We defined high and low MIG-6 expression by retrospectively selecting the most significant cutoff by log-rank testing. We also used the median expression of MIG-6 to dichotomize patients as a relatively unbiased means of stratifying beyond the CRS. We acknowledge that reaching conclusions using cut points from maximally selected statistics and multiple hypothesis testing requires further validation. The ultimate confirmation of the association between MIG-6 expression and survival after hepatectomy requires larger and perhaps prospective studies.

Despite these limitations, many of which are inevitable in research with human tumor specimens, we believe that our central conclusions are of interest: high MIG-6 expression is a negative prognostic feature in CRCLM; furthermore, determination of MIG-6 expression can augment the accuracy of prognostic schemes that rely on clinicopathologic data.

Author Contributions

D. B. D., D. T. R., and R. S. W. planned the studies. D. T. R., R. J. A., R. S. W., and D. B. D. wrote the manuscript. K. T., E. K. B., E. K. N., M. H. L., and R. J. A. prepared the figures and tables and contributed to data analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was approved and supported by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and by the Littlefield Family Foundation. The funding agencies were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript.

Declarations of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, Hess K, Curley SA. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. [discussion 825-817] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portier G, Elias D, Bouche O, Rougier P, Bosset JF, Saric J, Belghiti J, Piedbois P, Guimbaud R, Nordlinger B. Multicenter randomized trial of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid compared with surgery alone after resection of colorectal liver metastases: FFCD ACHBTH AURC 9002 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4976–4982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, Fuchs CS, Ramanathan RK, Williamson SK, Findlay BP, Pitot HC, Alberts SR. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:23–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tournigand C, Andre T, Achille E, Lledo G, Flesh M, Mery-Mignard D, Quinaux E, Couteau C, Buyse M, Ganem G. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:229–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [discussion 318-321] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konopke R, Kersting S, Distler M, Dietrich J, Gastmeier J, Heller A, Kulisch E, Saeger HD. Prognostic factors and evaluation of a clinical score for predicting survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases. Liver Int. 2009;29:89–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagashima I, Takada T, Nagawa H, Muto T, Okinaga K. Proposal of a new and simple staging system of colorectal liver metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6961–6965. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Jaeck D. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O'Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125–135. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aa2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Ribero D, Wu TT, Zorzi D, Hoff PM, Xiong HQ, Eng C, Lauwers GY, Mino-Kenudson M. Chemotherapy regimen predicts steatohepatitis and an increase in 90-day mortality after surgery for hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2065–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka K, Adam R, Shimada H, Azoulay D, Levi F, Bismuth H. Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of multiple colorectal metastases to the liver. Br J Surg. 2003;90:963–969. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam R, Pascal G, Castaing D, Azoulay D, Delvart V, Paule B, Levi F, Bismuth H. Tumor progression while on chemotherapy: a contraindication to liver resection for multiple colorectal metastases? Ann Surg. 2004;240:1052–1061. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000145964.08365.01. [discussion 1061-1054] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemeny N. Presurgical chemotherapy in patients being considered for liver resection. Oncologist. 2007;12:825–839. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arru M, Aldrighetti L, Castoldi R, Di Palo S, Orsenigo E, Stella M, Pulitano C, Gavazzi F, Ferla G, Di Carlo V. Analysis of prognostic factors influencing long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomlinson JS, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Kornprat P, Gonen M, Kemeny N, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, D'Angelica M. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zakaria S, Donohue JH, Que FG, Farnell MB, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM, Nagorney DM. Hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: value for risk scoring systems? Ann Surg. 2007;246:183–191. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupre A, Rehman A, Jones RP, Parker A, Diaz-Nieto R, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Malik HZ. Validation of clinical prognostic scores for patients treated with curative-intent for recurrent colorectal liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:1330–1336. doi: 10.1002/jso.24959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinicrope FA, Okamoto K, Kasi PM, Kawakami H. Molecular biomarkers in the personalized treatment of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang E, Miller LD, Ohnmacht GA, Liu ET, Marincola FM. High-fidelity mRNA amplification for gene profiling. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:457–459. doi: 10.1038/74546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grifantini R, Bartolini E, Muzzi A, Draghi M, Frigimelica E, Berger J, Ratti G, Petracca R, Galli G, Agnusdei M. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:914–921. doi: 10.1038/nbt728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishiwata T, Cho K, Kawahara K, Yamamoto T, Fujiwara Y, Uchida E, Tajiri T, Naito Z. Role of lumican in cancer cells and adjacent stromal tissues in human pancreatic cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson HW, Defamie V, Waterhouse P, Khokha R. TIMPs: versatile extracellular regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:38–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW, Raggi MC, Quan L, Yupei Z, Friess H, Erkan M, Kleeff J. Hypoxia inducible BHLHB2 is a novel and independent prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Seo BR, Fischbach C, Gourdon D. Fibronectin mechanobiology regulates tumorigenesis. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2016;9:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12195-015-0417-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao J, Yang JC, Ramachandran V, Arumugam T, Deng DF, Li ZS, Xu LM, Logsdon CD. TM4SF1 regulates pancreatic cancer migration and invasion in vitro and in vivo. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:740–750. doi: 10.1159/000445664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neesse A, Wagner M, Ellenrieder V, Bachem M, Gress TM, Buchholz M. Pancreatic stellate cells potentiate proinvasive effects of SERPINE2 expression in pancreatic cancer xenograft tumors. Pancreatology. 2007;7:380–385. doi: 10.1159/000107400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anastasi S, Lamberti D, Alema S, Segatto O. Regulation of the ErbB network by the MIG-6 feedback loop in physiology, tumor suppression and responses to oncogene-targeted therapeutics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;50:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang YW, Vande Woude GF. MIG-6, signal transduction, stress response and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:507–513. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferby I, Reschke M, Kudlacek O, Knyazev P, Pante G, Amann K, Sommergruber W, Kraut N, Ullrich A, Fassler R. MIG-6 is a negative regulator of EGF receptor-mediated skin morphogenesis and tumor formation. Nat Med. 2006;12:568–573. doi: 10.1038/nm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park E, Kim N, Ficarro SB, Zhang Y, Lee BI, Cho A, Kim K, Park AKJ, Park WY, Murray B. Structure and mechanism of activity-based inhibition of the EGF receptor by MIG-6. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:703–711. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henrich KO, Schwab M, Westermann F. 1p36 tumor suppression—a matter of dosage? Cancer Res. 2012;72:6079–6088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YW, Staal B, Su Y, Swiatek P, Zhao P, Cao B, Resau J, Sigler R, Bronson R, Vande Woude GF. Evidence that MIG-6 is a tumor-suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2007;26:269–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amatschek S, Koenig U, Auer H, Steinlein P, Pacher M, Gruenfelder A, Dekan G, Vogl S, Kubista E, Heider KH. Tissue-wide expression profiling using cDNA subtraction and microarrays to identify tumor-specific genes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:844–856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anastasi S, Sala G, Huiping C, Caprini E, Russo G, Iacovelli S, Lucini F, Ingvarsson S, Segatto O. Loss of RALT/MIG-6 expression in ERBB2-amplified breast carcinomas enhances ErbB-2 oncogenic potency and favors resistance to herceptin. Oncogene. 2005;24:4540–4548. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anastasi S, Fiorentino L, Fiorini M, Fraioli R, Sala G, Castellani L, Alema S, Alimandi M, Segatto O. Feedback inhibition by RALT controls signal output by the ErbB network. Oncogene. 2003;22:4221–4234. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiorentino L, Pertica C, Fiorini M, Talora C, Crescenzi M, Castellani L, Alema S, Benedetti P, Segatto O. Inhibition of ErbB-2 mitogenic and transforming activity by RALT, a mitogen-induced signal transducer which binds to the ErbB-2 kinase domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7735–7750. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7735-7750.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong JW, Lee HS, Lee KY, White LD, Broaddus RR, Zhang YW, Vande Woude GF, Giudice LC, Young SL, Lessey BA. MIG-6 modulates uterine steroid hormone responsiveness and exhibits altered expression in endometrial disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8677–8682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903632106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang YW, Su Y, Lanning N, Swiatek PJ, Bronson RT, Sigler R, Martin RW, Vande Woude GF. Targeted disruption of MIG-6 in the mouse genome leads to early onset degenerative joint disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11740–11745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505171102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endo H, Okami J, Okuyama H, Nishizawa Y, Imamura F, Inoue M. The induction of MIG-6 under hypoxic conditions is critical for dormancy in primary cultured lung cancer cells with activating EGFR mutations. Oncogene. 2017;36:2824–2834. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiorini M, Ballaro C, Sala G, Falcone G, Alema S, Segatto O. Expression of RALT, a feedback inhibitor of ErbB receptors, is subjected to an integrated transcriptional and post-translational control. Oncogene. 2002;21:6530–6539. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hackel PO, Gishizky M, Ullrich A. MIG-6 is a negative regulator of the epidermal growth factor receptor signal. Biol Chem. 2001;382:1649–1662. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin N, Cho SN, Raso MG, Wistuba I, Smith Y, Yang Y, Kurie JM, Yen R, Evans CM, Ludwig T. MIG-6 is required for appropriate lung development and to ensure normal adult lung homeostasis. Development. 2009;136:3347–3356. doi: 10.1242/dev.032979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ettenberg SA, Rubinstein YR, Banerjee P, Nau MM, Keane MM, Lipkowitz S. cbl-b inhibits EGF-receptor-induced apoptosis by enhancing ubiquitination and degradation of activated receptors. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 1999;2:111–118. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyatt DC, Ceresa BP. Cellular localization of the activated EGFR determines its effect on cell growth in MDA-MB-468 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3415–3425. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinehr R, Haussinger D. CD95 death receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in liver cell apoptosis and regeneration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;518:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rush JS, Quinalty LM, Engelman L, Sherry DM, Ceresa BP. Endosomal accumulation of the activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:712–722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wendt MK, Williams WK, Pascuzzi PE, Balanis NG, Schiemann BJ, Carlin CR, Schiemann WP. The antitumorigenic function of EGFR in metastatic breast cancer is regulated by expression of MIG-6. Neoplasia. 2015;17:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu J, Keeton AB, Wu L, Franklin JL, Cao X, Messina JL. Gene 33 inhibits apoptosis of breast cancer cells and increases poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-1040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang X, Izumchenko E, Solis LM, Kim MS, Chatterjee A, Ling S, Monitto CL, Harari PM, Hidalgo M, Goodman SN. The relative expression of MIG-6 and EGFR is associated with resistance to EGFR kinase inhibitors. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boopathy GTK, Lynn JLS, Wee S, Gunaratne J, Hong W. Phosphorylation of MIG-6 negatively regulates the ubiquitination and degradation of EGFR mutants in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cell Signal. 2018;43:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z, Raines LL, Hooy RM, Roberson H, Leahy DJ, Cole PA. Tyrosine phosphorylation of MIG-6 reduces its inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2372–2376. doi: 10.1021/cb4005707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pitroda SP, Khodarev NN, Huang L, Uppal A, Wightman SC, Ganai S, Joseph N, Pitt J, Brown M, Forde M. Integrated molecular subtyping defines a curable oligometastatic state in colorectal liver metastasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1793. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]