Abstract

Human gut microbiome studies are increasing at a rapid pace to understand contributions of the prokaryotic life to the innate workings of their eukaryotic host. Majority of studies focus on the pattern of gut microbial diversity in various diseases, however, understanding the core microbiota of healthy individuals presents a unique opportunity to study the microbial fingerprint in population specific studies. Present study was undertaken to determine the core microbiome of a healthy population and its imputed metabolic role. A total of 8990, clone library sequences (> 900 bp) of 16S rRNA gene from fecal samples of 43 individuals were used. The core gut microbiota was computed using QIIME pipeline. Our results show the distinctive predominance of genus Prevotella and the core composition of genera Prevotella, Bacteroides, Roseburia and Megasphaera in the Indian gut. PICRUSt analysis for functional imputation of the microbiome indicates a higher potential of the microbiota for carbohydrate metabolism. The presence of core microbiota may indicate key functions played by these microbes for the human host.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12088-018-0742-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Core microbiome, Indian gut microbiome, Gut microbiota

The human gut microbiome consists of a complex community of microorganisms that harbor in the gastrointestinal tract. The gut microbiota contributes more number of genes than human genome, is responsible for key functions ranging from digesting complex food material, training immune cells, maintaining gut barrier integrity, synthesizing essential vitamins and metabolites, degradation of xenobiotics, development of bones and regulation of behavior via the gut-brain axis [1–14]. The metabolic activities performed by the gut microbiome is often as complex as an organ and hence it is now being appreciated and studied in much detail. While the diversity of the microbiota helps us to understand the underlying ecology, the composition of core microbiota, often referred as the “core microbiome” is necessary to understand the focus of metabolic functions performed by these microbes. A good understanding of the core microbiome can help to identify microbes which are essential to the functioning of the population specific microbiome.

Here we explore the possibility of understanding the core microbiome of a healthy Indian population. A “core microbiota” is a subset of the microbial community that is shared between the observed population [15]. It may not always represent the most dominant phyla but can be thought to be important for certain critical metabolic functions. This study is a meta-analyses of the clone library sequences from healthy individuals which were pooled together from previously available data (see Table 1). The advantage of using clone library sequences (approx. 900 bp) is to determine the identity of the core taxa with high reliability. These sequences represent a population of 43 healthy individuals (13 females and 30 males) in the age range 14–62 from urban and semi-urban locales of Pune and Kolhapur districts in Maharashtra state (see Supplementary Table I). The selection criteria employed for determining their health status was no history of gastrointestinal diseases, no genetic disorders and no antibiotic or pre-biotic treatment in the 3 months prior to sampling.

Table 1.

Details of clone library sequences used

| Study | Individuals | Clone library sequences | NCBI accession nos. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 1313 | JX850071–JX850775; JX851389–JX851695 |

| 2 [16] | 7 | 2502 | KF864681–KF866127; KF232358–KF233412 |

| 3 | 7 | 1038 | KT924513–KT925529 |

| 4 [17] | 20 | 3237 | GU954553–GU957822 |

| 5 [18] | 5 | 900 | JQ264784–JQ265743 |

| Total | 43 | 8990 |

The diversity analysis and determination of core microbiome was computed using Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) [19]. Functional analysis was explored using online Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) Galaxy tool [20] which allows for gene prediction based upon the 16S rRNA marker gene and the potential of the core microbiome was explored using the comparative genomics tool of the PATRIC [21] database using the available representative genomes of the core taxa from NCBI.

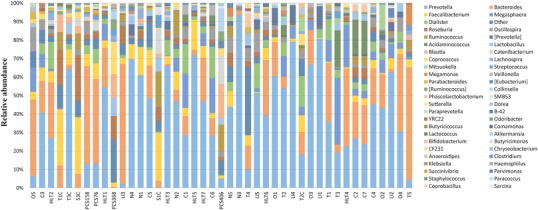

QIIME, version 1.7, was used for computing bacterial composition and determination of core microbiome. OTU’s were generated by closed reference OTU picking method in QIIME. The community landscape at phylum level is dominated by Bacteroides (54.1%) and Firmicutes (43.6%), followed by phyla Proteobacteria (0.8%), Tenericutes (0.8%) and Actinobacteria (0.5%) (see Supplementary Figure 1). The community structure at the genus level was found out to be dominated by genus Prevotella (34.7%) followed mainly by Bacteroides (15.2%), Faecalibacterium (5.6%), Megasphaera (4.7%) and Dialister (3.9%). See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Genus-level distribution

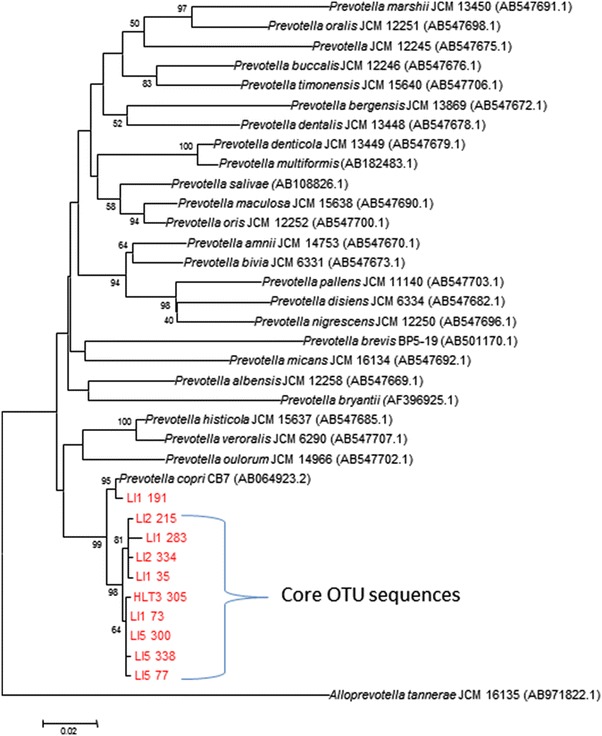

The core microbiota was computed in QIIME and the composition was recorded as an output from 50 to 100% of population in intervals of every 5% (11 intervals). QIIME analysis for core microbiota revealed the presence of genus Prevotella in 80% of the population while 55% of the population harbored genus Megasphaera, Roseburia and Bacteroides along with Prevotella in their gut. Taxonomic assignment up to species level of the core OTU’s was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis of the sequences retrieved from the respective core OTU. Briefly, the analysis involved aligning 16S rRNA gene sequences from core OTU with 10 or more known reference sequences of the same genus in MEGA5 [22] using CLUSTAL W [23] and phylogeny construction by Neighbor Joining method with Kimura 2-parameter model. This analysis revealed the taxonomic classification of the members of core gut microbiota as Prevotella copri (Fig. 2), Megasphaera elsdenii, Eubacterium rectale, Bacteroides coprocola and Bacteroides vulgatus (see Supplementary Figure 2, 3). Although the sequences from core OTU showed taxonomic identity as Prevotella copri using GreenGenes database, phylogenetic analysis reveals distinct clade which we believe is indicative of a different species of Prevotella present in Indian population. Nucleotide BLAST of the sequence from the Megasphaera core OTU also revealed 99% similarity with Megasphaera indica as opposed to GreenGenes assigned taxonomy as M.elsdenii.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for taxonomic classification: Prevotella copri

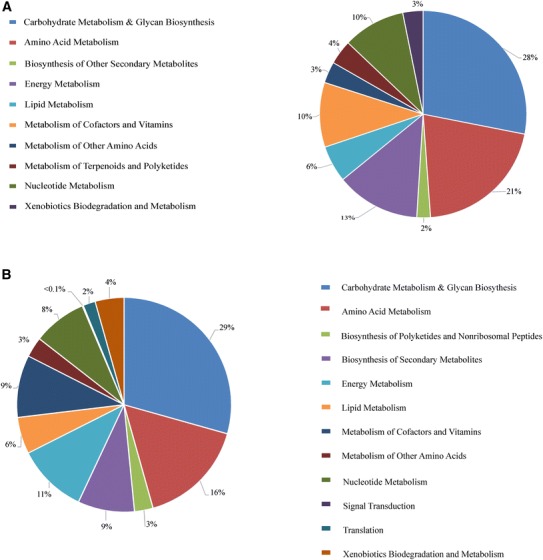

The functional contribution of genes from the microbiota was predicted using the PICRUSt online Galaxy tool by uploading the OTU BIOM table generated using QIIME. PICRUSt analysis showed higher proportion of genes for carbohydrate degradation, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides, xenobiotic degradation and other energy yielding pathways (Fig. 3a). Of note, genes encoding enzymes like sialidases, glucosidases and mannosidases responsible for degradation of complex oligosaccharides were found prominently, suggesting their possible role in carbohydrate degradation by microbes in gut. A higher potential of genes for multiple sugar transporters was also seen.

Fig. 3.

a PICRUSt analysis showing potential of microbiome for various biochemical pathways. b PATRIC analysis indication percentage of genes present for each biochemical pathway

PATRIC (analysis was performed for comparative genomics to gain insights into their metabolic functions and to understand the establishment as core microbial species in Indian gut. The reference genomes of the organisms present as core microbiota were used in the comparative tool of PATRIC database and showed contribution to a total of 133 core pathways (see Supplementary Table 2). Amongst the major biochemical pathways, approximately 30% of genes are seen contributing for carbohydrate metabolism including metabolism of various sugar substrates, metabolic pathways and glycan biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 3b). These observations can be supported with the average higher consumption of carbohydrate-rich and plant-derived foods in the diet of Indian population [24]. Collectively, these findings suggest association of carbohydrate rich diet in enrichment of gut bacteria with diverse CAZymes in the Indian population. While the genomes of core microbiome used for PATRIC comparative analysis are reference genomes reported from the western populations and closely resemble the taxonomic identities, we believe that the actual organisms present in the Indian gut may be indeed different strains which are closely related to the reference organisms.

Understanding the composition of core microbiota in healthy individuals can be used for insights in defining a healthy microbial fingerprint and can be used for comparative analysis in healthy V/s dysbiosis condition and also provides an insight into the gut functions of the microbiome for a particular population. The predominance of Prevotella and Megasphaera was first reported by Bhute et al. [25] in the Indian gut and this study further strengthens the finding.

Indian population is known for its dietary and geographical variety, unique family structure, ethnic diversity and the presence of many endemic tribes. The presence of core microbiota in the sample population irrespective of these variations may indicate key functions played by these microbes. To better understand the interplay of microbes in our diverse population, baseline studies highlighting important and unique microbes to the Indian population must be the future course of research. A drawback of using clone library sequences as compared to NGS techniques is the reflection of dominant phyla from the sample. To overcome this bias, culture based studies along with high throughput sequencing for a larger population size is the need of the hour to characterize the gut microbial diversity of healthy Indian individuals in greater detail. However this study emphasizes the importance of generating a baseline microbial profile of the population, applications of which may range from microbial phylogeography to future medical intervention studies such as population specific drug administration.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of faculty from Department of Microbiology, Modern College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Ganeshkhind, Pune. We extend our thanks to Dr. Shrikant Bhute, Dr. Mangesh Suryawanshi, Dr. Deepak Patil, Dr. Nachiket Marathe, Diptaraj Chaudhari and Sudarshan Shetty for their support. We also acknowledge the support extended by all lab members at the YSS lab and NCMR.

Author’s Contribution

YSS and DD conceptualized the work. AK performed the bioinformatic analysis, compiled the data and wrote the manuscript. YSS, DD and SK gave crucial inputs for analysis and manuscript revision.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalog established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inman M. How bacteria turn fiber into food. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiome shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flint JH, Scott PK, Louis P, Duncan HS. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:577–589. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holzer P, Farzi A. Neuropeptides and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;817:195–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings JH, MacFarlane GT. Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1997;21:357–365. doi: 10.1177/0148607197021006357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björkstén B, et al. Allergy development and the intestinal microflora during the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:516–520. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guarner F, Malagelada J. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. 2003;361:512–519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sears CL. A dynamic partnership: celebrating our gut flora. Anaerobe. 2005;11:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhoff U. Who controls the crowd? New findings and old questions about the intestinal microflora. Immunol Lett. 2005;99:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purohit HJ. Gut-bioreactor and human health in future. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s12088-017-0697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood U, Bajaj A, Kumar R, Khurana S, Kalia VC. Infection and microbiome: impact of tuberculosis on human gut microbiome of Indian cohort. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:123–125. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0706-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suryavanshi MV, Bhute SS, Jadhav SD, Bhatia MS, Gune RP, Shouche YS. Hyperoxaluria leads to dysbiosis and drives selective enrichment of oxalate metabolizing bacterial species in recurrent kidney stone endures. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34712. doi: 10.1038/srep34712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil DP, Dhotre DP, Chavan SG, Sultan A, Jain DS, Lanjekar VB, Gangawani J, Shah PS, Todkar JS, Shah S, Ranade DR, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Molecular analysis of gut microbiota in obesity among Indian individuals. J Biosci. 2012;37:647–657. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marathe N, Shetty S, Lanjekar V, Ranade D, Shouche Y. Changes in human gut flora with age: an Indian familial study. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wattam AR, Davis JJ, Assaf R, et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D535–D542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha R, Anderson DE, McDonald SS, Greenwald P. Cancer risk and diet in India. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhute S, Pande P, Shetty SA, et al. Molecular characterization and meta-analysis of gut microbial communities illustrate enrichment of Prevotella and Megasphaera in Indian subjects. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:660. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.