Abstract

Mutations in the gene (GJA1) encoding connexin43 (Cx43) are responsible for several rare genetic disorders, including non-syndromic skin-limited diseases. Here we used two different functional expression systems to characterize three Cx43 mutations linked to palmoplantar keratoderma and congenital alopecia-1, erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva, or inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. In HeLa cells and Xenopus oocytes, we show that Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D all formed functional gap junction channels with the same efficiency as wild-type Cx43, with normal voltage gating and a unitary conductance of ~110 pS. In HeLa cells, all three mutations also localized to regions of cell-cell contact and displayed a punctate staining pattern. In addition, we show that Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D significantly increase membrane current flow through formation of active hemichannels, a novel activity that was not displayed by wild-type Cx43. The increased membrane current was inhibited by either 2 mM calcium, or 5 µM gadolinium, mediated by hemichannels with a unitary conductance of ~250 pS, and was not due to elevated mutant protein expression. The three Cx43 mutations all showed the same gain of function activity, suggesting that augmented hemichannel activity could play a role in skin-limited diseases caused by human Cx43 mutations.

Introduction

Connexins (Cx) are a family of proteins that make gap junction channels, and allow the direct passage of small molecules between adjacent cells1,2. Connexins oligomerize into hemichannels (also called connexons) that contain six connexin monomers during transit through the ER-Golgi pathway3,4. Hemichannels are transported to the plasma membrane, where they can act as functional channels on their own5–7, or move to regions of cell contact and dock with a partner hemichannel in an adjacent cell to form a gap junction channel8. Gap junction channels formed by different connexins have unique gating, conductance and permeability characteristics8–13, and these functional differences are important, since one type of connexin cannot be functionally replaced by a different connexin in genetically engineered mice14–16. The activity of hemichannels can change under conditions of stress, allowing the flux of molecules like Ca2+, ATP, glutamate, or NAD+ across the cell membrane and provoking a variety of physiological responses17,18.

Mutations in ten of the human connexin genes have already been linked to twenty-eight distinct genetic diseases19. Eleven of these are skin disorders with an overlapping spectrum of phenotypes that are caused by mutations in five of the connexin genes20. Mutations in one of these genes, GJA1 gene encoding Cx43, cause a number of rare genetic diseases, including skin disease20,21. The first GJA1 mutation identified in an isolated epidermal disorder was the Cx43-G8V mutation linked to palmoplantar keratoderma and congenital alopecia-1 (PPKCA1, also called keratoderma-hypotrichosis-leukonychia totalis)22. PPKCA1 is a dominant disorder characterized by severe hyperkeratosis, congenital alopecia and leukonychia23. Subsequently, the Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D mutations were found to cause erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva (EKVP)24. EKVP is another dominant disorder, which can be caused by mutations in three different connexin genes20. It is characterized by hyperkeratosis that can be widespread over the body, or limited to a small area. About half of the patients with EKVP also have palmoplantar keratoderma25,26. In EKVP caused by Cx43 mutations, patients also had prominent white lunulae and periorificial darkening24. Finally, the same Cx43-A44V mutation linked to EKVP, was identified in a patient with inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN)27. ILVEN is characterized by pruritic, erythematous, hyperkeratotic papules linearly distributed along Blaschko’s lines, and is caused by somatic, rather than germline mutations28. The three Cx43 mutations linked so far to human genetic skin disease are all single amino acid substitutions whose functional consequences have not been fully characterized.

Studies of several mutations in other connexins linked to skin disease have suggested a generalized role for altered hemichannel activity in the connexin skin disorders20,29–32. Increases in hemichannel activity have been described for Cx26 mutations causing both Keratitis-Ichthyosis-Deafness (KID) syndrome and palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) with deafness33–36. Cx30 mutations associated with hidrotic ectodermal displaysia (HED) elicited large currents and increased ATP leakage in cells, consistent with altered hemichannel function37. In a similar fashion, Cx31 mutations causing EKVP were shown to result in increased hemichannel activity, ATP leakage, and necrotic cell death when expressed in transfected cells38. Even in the case of Cx43, the initial characterization of the Cx43-G8V mutation linked to PPKCA1 in transfected cells showed increased whole cell membrane current, Ca2+ influx, and cell death when compared to wild-type Cx43, which could have been mediated by an increase in the activity of hemichannels22.

Here we report the functional characterization of all three of the Cx43 mutations that have been linked to non-syndromic human skin disease thus far, Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D. Using cRNA injected Xenopus oocytes or transiently transfected HeLa cells, we demonstrate that all three mutations form functional gap junctions as efficiently as wild-type-Cx43, with no obvious differences in voltage gating, unitary conductance, protein expression, or cellular localization. We further observed that Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D all formed functional hemichannels with greatly increased membrane current flow, a feature not shared by wild-type Cx43. These results suggest that the augmentation of hemichannel function shared by all three mutations may play a role in the pathophysiology of human Cx43 mutations linked to skin disease.

Results

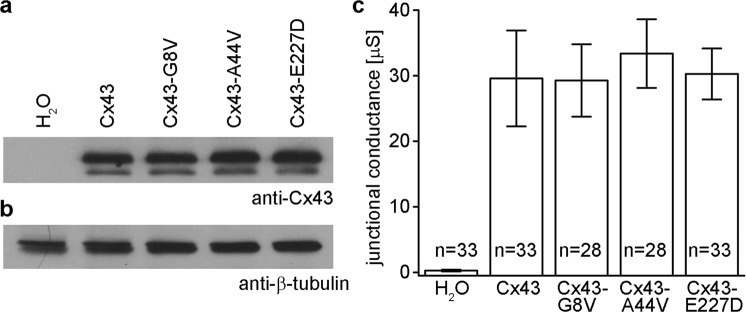

Wild-type and mutant forms of Cx43 show equivalent levels of protein expression in Xenopus oocytes

Equivalent protein expression of wild-type and mutant Cx43 was verified by western blotting of cRNA injected Xenopus oocytes. Immunoblotting for Cx43 revealed ~43 kDa bands of similar intensity in lanes corresponding to oocytes injected with either wild-type Cx43, Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, or Cx43-E227D cRNAs. No Cx43 band was detected in H2O injected control cells (Fig. 1a). When the blot was re-probed for β-tubulin, it was detected at similar intensity in all samples, confirming equal protein loading (Fig. 1b). These data showed that levels of Cx43 protein synthesis following cRNA injection were similar for mutant and wild-type Cx43.

Figure 1.

Wild-type and mutant forms of Cx43 are equivalently expressed and form functional gap junctions in paired Xenopus oocytes. (a) Equal amounts of membrane extracts were first probed with an antibody that recognized Cx43. H2O injected controls did not express Cx43 as expected. Wild-type Cx43, Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D were readily detected in lanes corresponding to each injection condition with similar band intensities. (b) To confirm equal sample loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody against β-tubulin, which was present at comparable levels in all lanes. (c) Gap junctional conductance levels for cell pairs expressing either wild-type, or mutant, forms of Cx43 were all significantly greater than the H2O injected negative controls (p < 0.05, one way ANOVA), but not significantly different from each other. Values are the mean ± SEM.

Cx43 mutations form functional gap junction channels in Xenopus oocytes

To examine the ability of Cx43 skin disease mutations to make gap junction channels, wild-type and mutant Cx43 were expressed in Xenopus oocyte pairs and gap junctional conductance was measured (Fig. 1c). Control oocyte pairs injected with water showed negligible conductance (0.28 µS), while cells with wild-type Cx43 channels had an average conductance of 29.6 µS. Cell pairs expressing Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, or Cx43-E227D had mean conductance levels of 29.3, 33.4 or 30.3 µS respectively. Conductance levels of cell pairs expressing either mutant, or wild-type, forms of Cx43 were all significantly greater than the H2O injected negative controls (one way ANOVA, p < 0.05), but not significantly different from each other, consistent with the equivalent levels of Cx43 protein expression (Fig. 1a). Thus, all three of the skin disease associated Cx43 mutations formed gap junction channels with macroscopic conductance levels equal to wild-type Cx43.

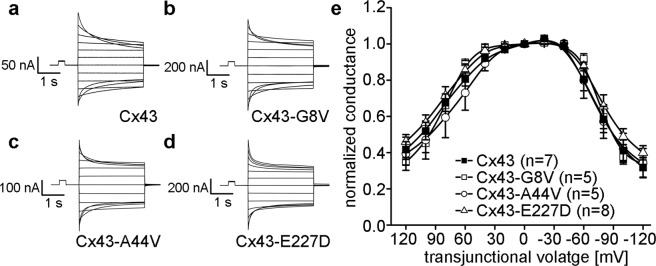

Skin disease mutations do not affect Cx43 voltage gating

To examine whether skin disease causing mutations altered the voltage gating properties of Cx43 gap junction channels, oocyte pairs were subjected to hyperpolarizing and depolarizing transjunctional potentials (Vj) while recording junctional currents (Ij). As previously described39–41, Ijs of wild-type Cx43 gap junction channels decreased symmetrically in a voltage-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Channels in cell pairs expressing Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, or Cx43-E227D (Fig. 2b–d) behaved in a similar fashion. Steady-state voltage gating was compared by plotting Vj (normalized to the value at ±20 mV) against Gj (Fig. 2e). Analysis of wild-type Cx43 showed an approximately symmetric decline in steady state conductance at increasing values of Vj, as has been reported previously33,40,42. Cell pairs expressing Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, or Cx43-E227D displayed steady state gating that strongly resembled that of wild-type Cx43.

Figure 2.

Cx43 mutations do not alter gap junction voltage gating. Oocyte pairs were subjected to hyperpolarizing and depolarizing transjunctional potentials (Vj) while recording junctional currents (Ij). (a) Wild-type Cx43 gap junction channels had Ijs that decreased symmetrically at higher values of Vj. Ijs between cell pairs expressing Cx43-G8V (b), Cx43-A44V (c), or Cx43-E227D (d) behaved in a similar fashion. (e) Steady-state voltage gating of wild-type Cx43 (filled squares) showed an approximately symmetric decline in steady state conductance at increasing values of Vj. Data from cell pairs expressing Cx43-G8V (open squares), Cx43-A44V (open circles), or Cx43-E227D (open triangles) were similar to wild-type Cx43.

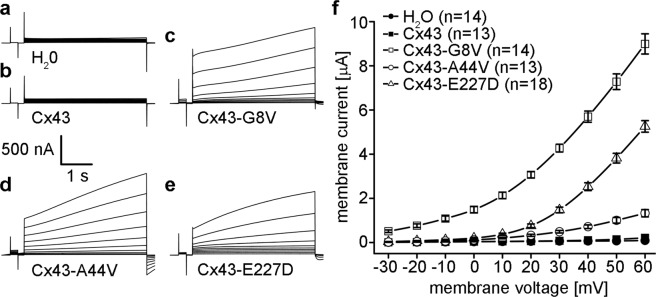

Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D all form active hemichannels in unpaired Xenopus oocytes

To test for changes in hemichannel activity, cRNAs encoding wild-type and mutant forms of Cx43 were injected into single Xenopus oocytes that had also received antisense oligonucleotides directed against the endogenous Xenopus Cx3843,44. Membrane currents were recorded while the cells were clamped to different membrane voltages. Oocytes injected with H2O instead of connexin cRNA showed insignificant current flow at membrane voltages between −30 and +60 mV (Fig. 3a). We found that oocytes expressing wild-type Cx43 also showed negligible membrane current flow between −30 and +60 mV (Fig. 3b). In sharp contrast, Xenopus oocytes expressing Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, or Cx43-E227D all displayed large outward hemichannel currents upon depolarization (Fig. 3c–e).

Figure 3.

Cx43 mutations induce large hemichannel currents in Xenopus oocytes. Single cells were clamped at a holding potential of −40 mV and subjected to voltage pulses ranging from −30 to +60 mV in 10 mV steps. H2O (a) and wild-type Cx43 (b) injected cells displayed negligible membrane currents. Cx43-G8V (c), Cx43-A44V (d), and Cx43-E227D (e) expressing oocytes displayed much larger hemichannel currents than wild-type Cx43. (f) Steady-state currents from each pulse were plotted as a function of membrane voltage. Steady state currents in wild-type Cx43 (filled squares) or H2O injected control cells (filled circles) were negligible at all tested membrane voltages. Cx43-G8V (open squares) expressing cells exhibited significantly increased steady-state currents at all voltages compared to either control or wild-type Cx43 oocytes. Cx43-A44V (open circles), or Cx43-E227D (open triangles) currents were similar to those observed in control cells at negative voltages, but increased at positive potentials. Data are the mean ± SEM.

To compare differences in hemichannel activity, mean currents were plotted against the membrane potential (Fig. 3f). H2O injected control cells, or wild-type Cx43 expressing cells showed minimal membrane currents at all tested voltages. The Cx43-G8V injected cells had much larger hemichannel currents than wild-type Cx43 injected cells at all tested membrane potentials. Cx43-A44V injected oocytes displayed membrane currents that were greater than wild-type Cx43 at membrane potentials ≥+20 mV. Cx43-E227D injected cells had larger membrane currents than wild-type Cx43 at membrane potentials ≥+10 mV. This increased membrane current implied the presence of augmented hemichannel activity by the Cx43 mutants associated with genetic skin disease.

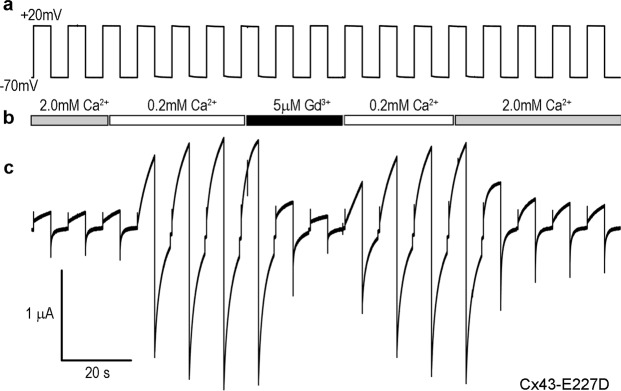

Connexin hemichannels are known to be blocked by the presence of extracellular cations such as calcium and gadolinium6,45,46. To confirm that currents observed in single cells expressing the Cx43 mutations were mediated by connexin hemichannels, oocytes were successively stepped from −70 mV to +20 mV while being perfused with extracellular medium containing either 2 mM Ca2+, 0.2 mM Ca2+, or 5 µM Gd3+. In an example shown for a Cx43-E227D expressing oocyte (Fig. 4), hemichannel currents were initially suppressed by the presence of 2 mM Ca2+, and increased markedly when the extracellular calcium in the perfusate was reduced tenfold to 0.2 mM. Cx43-E227D hemichannel currents were also efficiently suppressed by perfusion with 5 µM Gd3+, and recovered rapidly when the Gd3+ was washed out with medium containing 0.2 mM Ca2+. Finally, Cx43-E227D hemichannel currents were suppressed back to their initial levels by increasing the extracellular calcium back to 2.0 mM. On average, Cx43-E227D hemichannel currents were inhibited 90 ± 4% (mean ± SD, n = 3) following perfusion with 5 µM Gd3+. Similar results were obtained for Cx43-G8V (86 ± 9%, n = 3) and Cx43-A44V (87 ± 3%, n = 3). These data suggest that the increased membrane current seen in oocytes expressing mutant forms of Cx43 is due connexin hemichannel activity.

Figure 4.

Calcium and gadolinium ions block mutant Cx43 hemichannel activity. Oocytes expressing Cx43 mutations were sequentially stepped from −70 mV to +20 mV (a) while being perfused with medium containing 2 mM Ca2+, 0.2 mM Ca2+, or 5 µM Gd3+ (b). In the example shown for a Cx43-E227D expressing cell (c), hemichannel currents were initially suppressed by 2 mM Ca2+, and increased markedly when the extracellular calcium was reduced to 0.2 mM. Hemichannel currents were also suppressed by perfusion with 5 µM Gd3+, and recovered rapidly when Gd3+ was washed out with 0.2 mM Ca2+. Currents were suppressed again by increasing the extracellular calcium to 2.0 mM.

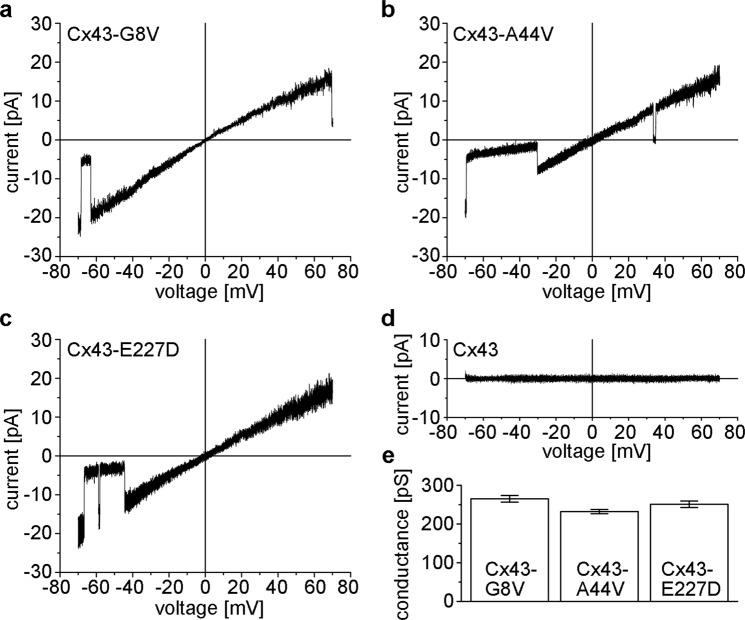

Single hemichannels formed by skin disease mutations

The conductance and gating of hemichannels formed by mutant Cx43 subunits was explored using cell-attached or excised patch recordings. Xenopus oocytes expressing mutant Cx43 subunits showed large-conductance channels in symmetric 140 mM KCl. Figure 5 shows currents of single Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D hemichannels obtained by applying ±70 mV voltage ramps. Open channel currents of Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D were largely linear over the voltage range whereas Cx43-G8V hemichannel currents exhibited slight inward rectification. Mean slope conductances, measured at Vm = 0 mV, were 265 ± 8.6 for Cx43-G8V (n = 5), 232 ± 5.5 for Cx43-A44V (n = 6), and 251 ± 8.4 (n = 7) for Cx43-E227D. Such large conductance channels were never observed in any of the Xenopus oocytes expressing wild-type Cx43.

Figure 5.

Representative examples of patch clamp recordings from cell-attached patches containing single Cx43-G8V (a), Cx43-A44V (b), and Cx43-E227D (c) hemichannels in symmetric 140 mM KCl solutions. Single hemichannel currents were recorded in response to 8-s voltage ramps between −70 and +70 mV. Current-voltage relations for Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D were linear, whereas those of Cx43-G8V showed slight inward rectification. All three mutations show closing transitions to subconductance states. Occasional transitions to the fully closed state are also seen (b). (d) Cell-attached patches from wild-type Cx43 injected oocytes failed to show single channel activity. (e) Mean slope conductances measured at Vm = 0 are similar for the three mutant hemichannels. Values represent the mean ± SEM from 5 to 7 recordings.

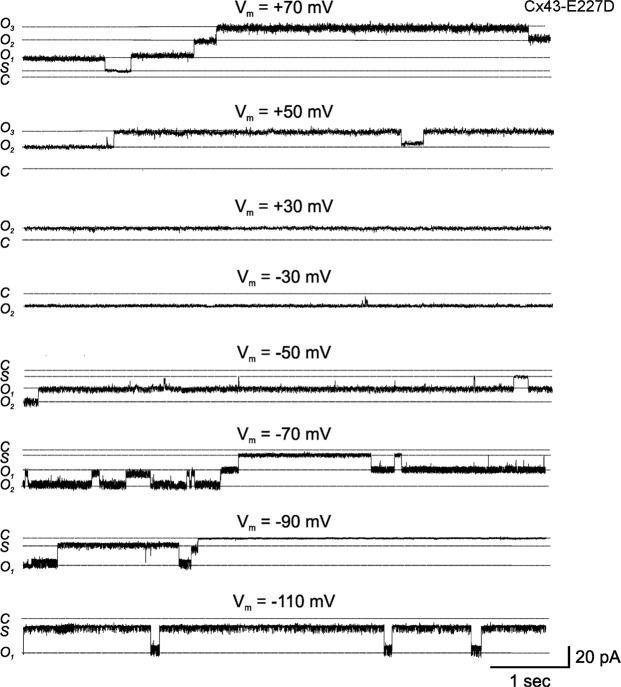

Our single-channel I–V relationships appeared to indicate that all three mutant Cx43 hemichannels could open at negative voltages. Figure 6 shows current traces from an oocyte expressing Cx43-E227D at different voltages. At positive voltages, Cx43-E227D channels were predominantly open (see traces at Vm = +30 mV, +50 mV and +70 mV). Occasional closures to subconductance states at voltages exceeding 50 mV were observed, but residence times in these states did not appear to occur in a voltage dependent manner. At small negative voltages, Cx43-E227D hemichannels showed a high open probability (see traces at Vm = −30 mV and −50 mV). With increasingly negative voltages, residence times decreased in the open state, and channels showed frequent closures to subconductance states. Although slow transitions between open and fully closed states were observed (see trace at Vm = −90 mV), they were infrequent and appeared to exhibit weak sensitivity to voltage. Similar results were obtained with Cx43-G8V and Cx43-A44V.

Figure 6.

Gating of single Cx43-E227D hemichannels at positive and negative voltages. Representative examples of recordings from a Cx43-E227D expressing oocyte in a cell-attached patch configuration containing one to two open channels at voltages ranging from −110 to +70 mV. Cx43-E227D hemichannels were predominantly open at inside positive voltages. Occasional closures to subconductance states were observed at high positive voltages. In contrast, Cx43-E227D hemichannels showed voltage-dependent closures to negative voltages. While channels are predominantly open at −30 mV, dwell times in the open state decreased with hyperpolarization to −50, −70 and −90 mV. Residence in subconductance states or the fully closed state was favored at the more hyperpolarized voltages. The zero current level, i.e. the fully closed state (C), the current levels of one (O1) or two fully open hemichannels (O2) and that of the subconductance state (S) are depicted by dotted lines. The zero current level was determined as described in Methods.

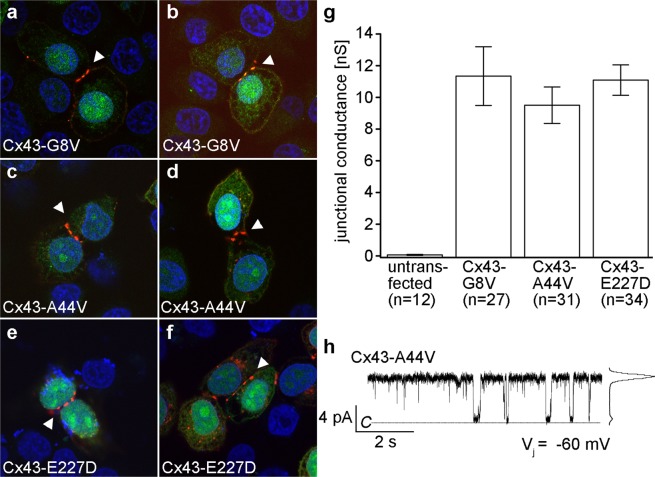

Cx43 mutations also form gap junctions in transfected HeLa cells

To determine mutant protein localization and function in mammalian cells, gap junctional communication-deficient HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the mutant forms of Cx43. Immunofluorescent staining verified protein expression and localization for Cx43-G8V (Fig. 7a,b), Cx43-A44V (Fig. 7c,d), and Cx43-E227D (Fig. 7e,f). All three mutations showed proper trafficking to the cell membrane, especially at the regions of cell-to-cell contact, as shown by punctate staining (white arrowheads). Thus, Cx43 mutant proteins were properly expressed, and junctionally targeted in mammalian cells.

Figure 7.

Expression of mutant Cx43 in transfected HeLa cells results in targeting to gap junction plaques and formation of functional intercellular channels. Cx43-G8V (a,b), Cx43-A44V (c,d), and Cx43-E227D (e,f) transfected cells (blue DAPI stain) displayed a strong Cx43 (red) labeling that concentrated at cell-to-cell interfaces (white arrowheads) and correlated with GFP (green) fluorescence. (g) Measurement of gap junctional coupling in transfected cell pairs showed that all three Cx43 mutations induced similar high levels of conductance. (h) A single gap junction channel recording for Cx43-A44V shows transitions between the fully open state and closed state with a unitary conductance of 113 pS. Data are the mean ± SEM.

The ability of Cx43 mutants to form functional gap junction channels was also analyzed by dual whole cell patch clamp in the transiently transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 7g). As expected10,47, untransfected HeLa cells failed to form gap junctions, with a mean conductance of 0.06 ± 0.03 nS. Consistent with our results obtained in paired Xenopus oocytes above (Fig. 1), the mean junctional conductance of Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D cell pairs were 11.3 ± 1.9, 9.5 ± 1.2, and 11.1 ± 1.0 nS, respectively, values that were more than two orders of magnitude greater than the untransfected cell pairs, but not statistically different from each other (p > 0.05, one way ANOVA).

Previous biophysical studies have documented that wild-type Cx43 forms gap junction channels with a unitary conductance of ~110 pS39,48–50. To determine if the Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D mutations altered single channel conductance, unitary currents were measured in poorly coupled cell pairs. An example of a single-channel current recorded from a cell pair transfected with Cx43-A44V is shown in Fig. 7h. At a transjunctional voltage of −60 mV, the single-channel was primarily in the open state, with a few transitions to the closed state. An amplitude histogram of the recording, illustrated on the right of the trace, showed a major peak at 6.8 pA, corresponding to the fully open state, and yielding a unitary conductance of 113 pS. The Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D mutations all displayed unitary conductance of gap junction channels similar to wild-type Cx43, with mean values (±SEM) of 110 ± 9 (n = 2), 113 ± 8 (n = 3), and 109 ± 8 pS (n = 3) respectively.

Discussion

We have functionally characterized three human Cx43 mutations linked to non-syndromic skin-limited genetic disease. Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D all formed functional gap junctions as efficiently as wild-type Cx43, with similar voltage gating, unitary conductance, protein expression, and cellular localization. In addition, Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D formed functional hemichannels that mediated greatly increased membrane current flow. We found that wild-type Cx43 failed to form ion-conducting hemichannels under physiological conditions, as has been previously reported46,51–53. The shared gain of hemichannel function by Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D suggests that augmented hemichannel activity could be a common feature of Cx43 mutations linked to skin disease.

In the original clinical reports of these mutations, Cx43-G8V was reported to target to cellular interfaces and support the intercellular passage of fluorescent dye as a GFP tagged construct22, consistent with our experimental data. In contrast, Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D failed to localize at cell-cell junctions, and aggregated in the Golgi apparatus when transfected into HeLa cells as hemagglutinin-tagged constructs, with no test of channel function in this study24. In contrast to this report, we found that untagged versions of both Cx43-A44V and Cx43-E227D targeted to cellular interfaces and supported gap junctional coupling in two different expression systems. In addition, the gap junction channels that we recorded had unitary conductance and voltage gating properties that would be expected for Cx43. We suspect that the hemagglutinin-tag, or possible high levels of overexpression, may have altered the improper localization reported by Boyden et al.24.

Our single channel studies further revealed that the unitary conductance of hemichannels formed by all three mutants is ~250 pS, close to twice that of their corresponding gap junction channels, as would expected from the series docking of two identical hemichannels in a cell-cell channel8. We did not observe single hemichannels in wild-type Cx43 injected oocytes, but our values of unitary conductance for the three different mutants are similar to the ∼220 pS unitary conductance previously reported for wild-type Cx43 hemichannels in HeLa cells54,55. In contrast, the gating characteristics of hemichannels formed by Cx43 mutants exhibit significant differences from previous reports of wild-type Cx43 hemichannels55,56. In solutions containing Ca2+/EGTA (free Ca2+ concentrations <10−7 M), we found that all three mutant hemichannels primarily resided in the fully open state at low to moderate inside negative voltages. All of the mutant hemichannel currents also exhibited gating to subconductance states at negative voltages, whereas depolarizing voltages produced only brief transitions to intermediate states. These hemichannel properties are markedly different from those of wild-type Cx43, which required depolarization exceeding +40 mV for their activation, and exhibited long-lived transitions to subconductance states at high positive voltages. Complete characterization the gating, ion permeability, and pharmacology of Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D hemichannels will require additional studies.

Cx43 is a widely expressed protein, and is present in the skin across the epidermis21,57,58. Most mutations in the GJA1 gene, encoding Cx43, result in oculodentodigital dysplasia (ODDD)59, a disorder that manifests with neuropathies, facial, dental, and digit abnormalities and very rarely skin disease60. Recently, GJA1 mutations were identified in patients with three distinct, non-syndromic, skin-limited diseases, who lacked any of the diagnostic features of ODDD. Cx43-G8V was found in three patients from two unrelated families with PPKCA122, Cx43-A44V was detected in two unrelated patients, one with EKVP and the other with ILVEN24,27, and Cx43-E227D was identified in two unrelated patients with EKVP24. There is overlap in the clinical features presented in these disorders, suggesting that a common functional consequence, such as augmented hemichannel activity, could underlie the pathology resulting from the three distinct mutations.

As described in the introduction, analysis of mutations in other connexins associated with epidermal disorders has suggested a general role for augmented hemichannel function in the pathology of skin disease19,20. Other recent studies have suggested that wild-type Cx43 hemichannel activity was promoted by Cx26 mutations through the formation of heteromeric hemichannels. The first study examined the KID syndrome mutation Cx26-S17F. Although Cx26-S17F was unable to form hemichannels or gap junction channels when expressed alone61, it showed significantly increased hemichannel activity when co-expressed with wild-type Cx4335. The second showed that two PPK mutations, Cx26-H73R and Cx26-S183F, both failed to form hemichannels when expressed alone in Xenopus oocytes. Like Cx26-S17F, co-expression of either Cx26 PPK mutant with Cx43 showed significantly increased hemichannel activity, compared to Cx43 alone. Co-immunoprecipitation showed that Cx43 was efficiently pulled down with either Cx26-H73R and Cx26-S183F, confirming the formation of heteromeric hemichannels33. In the present work, we found that expression of skin disease causing Cx43 mutations resulted in augmented membrane currents mediated by active hemichannels. The addition of the data for Cx43, to the cumulative reports on Cx26, Cx30 and Cx31 mutations, makes a strong case that increased hemichannel activity linked to connexin mutations associated with epidermal disorders may contribute to disease pathology.

Methods

Molecular cloning

Human Cx43 was cloned into pCS2+ 62 for functional studies as previously described33. Mutant Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D were generated by site directed mutagenesis63 using human Cx43 as a template. Cx43-G8V, Cx43-A44V, and Cx43-E227D were cloned into pBlueScript II (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and sequenced prior to being subcloned into pCS2+ for Xenopus oocyte expression, or pIRES2-EGFP2 (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) for expression in HeLa cells47.

In vitro transcription, oocyte microinjection, and pairing

Cx43 constructs in pCS2+ were linearized with Not1 and cRNA was transcribed using the SP6 mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Austin, TX). Xenopus laevis oocytes were purchased (Xenopus 1, Dexter, MI) and cultured in in modified Barth’s (MB) medium47. Oocytes were injected with 10 ng of antisense oligonucleotide against Xenopus Cx3843,44, followed by connexin transcripts (5 ng/cell). Antisense Cx38 oligonucleotide treated oocytes injected with water, instead of cRNA, served as a negative control.

Hemichannel current recording

Whole cell hemichannel currents were recorded 24 hours after cRNA injection into Xenopus oocytes using a GeneClamp 500 amplifier operated by a PC-compatible computer using a Digidata 1440A interface and pClamp 10 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Electrodes (1.5 mm diameter glass, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) were pulled to a resistance of 1–2 MΩ (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and filled with 3 M KCl, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. In most cases, cells were recorded in MB medium without added calcium34. Hemichannel current-voltage (I–V) curves were obtained by clamping cells at −40 mV and imposing voltage steps in 10 mV increments ranging from −30 to +60 mV. For perfusion experiments testing hemichannel block by cations, extracellular solutions were exchanged using a six channel perfusion valve control system and a slotted bath oocyte recording chamber (VC-6 and RC-1Z, Warner instruments, Hamden, CT).

For patch-clamp recordings of single-hemichannel currents, Xenopus oocytes were manually devitellinized in a hypertonic solution consisting of (in mM) 220 Na-aspartate, 10 KCl, 2 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, and then placed in ND96 medium for recovery. Individual oocytes were moved to a recording chamber (RC-28; Warner Instruments) containing the patch pipette solution, which consisted of (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, and 3 EGTA, pH adjusted to 8.0 with KOH. The bath compartment was connected via a 3-M agar bridge to a ground compartment containing the same IPS solution. Single-hemichannel records from voltage steps and ramps were leak subtracted by measuring the leak current during full-closing events and extrapolating linearly with voltage.

Recording of gap junctional conductance

In Xenopus oocyte pairs, junctional conductance (Gj) was measured by initially clamping both cells in a pair at −40 mV (a transjunctional potential (Vj) of zero). One cell was subjected to alternating pulses of ±20 mV and the current produced by the change in voltage was recorded in the second cell, which was equal in magnitude to the junctional current (Ij). Conductance was calculated by dividing Ij by the voltage difference, Gj = Ij/(V1 − V2)64. Gating properties were determined by recording the junctional current in response to hyperpolarizing or depolarizing Vjs in 20-mV steps. Steady-state currents (Ijss) were measured at the end of the voltage pulse. Steady-state conductance (Gjss) was calculated by dividing Ijss by Vj, normalized to ± 20 mV, and plotted against Vj.

For recordings of single channel junctional currents, HeLa, or N2A cells were transfected with cDNA corresponding to the mutant connexins. Junctional currents were measured using the dual whole cell patch-clamp technique as described previously65. Single gap junction channel currents were visualized during washout of 100% CO2 saturated media, which uncouples cells completely. All electrophysiological measurements were obtained using Axopatch 1D patch clamp amplifiers (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Data were acquired by using pClamp 9.2 software; analysis was performed with pClamp 9.2. Currents were filtered at 0.5–1 kHz and sampled at 2–5 kHz.

Western blotting

Oocytes extracts were prepared as previously described66, run on 12% SDS gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose. Western blots were first blocked with 5% milk 0.1% Tween20 in TBS, then probed with polyclonal antibodies against Cx43 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA), followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratories and GE Healthcare). A monoclonal β-tubulin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used as a loading control.

Cell transfection

HeLa cells were grown to 50% confluence on 22 mm2 coverslips and transfected with wild-type or mutant Cx43 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described10,47,67. To facilitate cell survival, the calcium concentration in the culture media was elevated to 4 mM by the addition of supplemental CaCl2 24 hours after transfection.

Immunofluorescent staining of transfected cells

HeLa cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS 24–48 hours after transfection and blocked with 5% BSA dissolved in PBS with 0.02% NaN3 and 0.1% Tx-100 added. Cells were immunostained with a polyclonal Cx43 antibody followed by a Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Cells were photographed on a BX51 microscope using a DP72 digital camera (Olympus America, Waltham, MA).

Statistical analysis

Differences in data sets were analyzed for statistical significance with Origin 6.1 software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). Multiple comparisons were done with one-way ANOVA. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the indicated number of experiments. Statistical significance was designated for analyses with p < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Mark Hannigan for assistance with generation of mutant Cx43 constructs. This work was supported by NIH grants EY013163 & EY026911 to T.W.W., and EY028170 to M.S.

Author Contributions

M.S., T.F.J., A.G.C., L.L., N.S., C.S. and T.W.W. performed experiments, M.S., L.L., C.S. and T.W.W. designed experiments and contributed to data analysis, and M.S. and T.W.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-37221-2.

References

- 1.Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL. Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinken M. Introduction: connexins, pannexins and their channels as gatekeepers of organ physiology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2775–2778. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1958-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das Sarma J, Wang F, Koval M. Targeted gap junction protein constructs reveal connexin-specific differences in oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20911–20918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laird DW. Life cycle of connexins in health and disease. Biochem J. 2006;394:527–543. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Hemi-gap-junction channels in solitary horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J Physiol. 1992;445:201–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebihara L, Steiner E. Properties of a nonjunctional current expressed from a rat connexin46 cDNA in Xenopus oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:59–74. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malchow RP, Qian H, Ripps H. Evidence for hemi-gap junctional channels in isolated horizontal cells of the skate retina. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:237–245. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris AL. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q Rev Biophys. 2001;34:325–472. doi: 10.1017/S0033583501003705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanaporis G, et al. Gap junction channels exhibit connexin-specific permeability to cyclic nucleotides. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:293–305. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mese G, Valiunas V, Brink PR, White TW. Connexin26 deafness associated mutations show altered permeability to large cationic molecules. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C966–974. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00008.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bukauskas FF, Verselis VK. Gap junction channel gating. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1662:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris AL. Connexin channel permeability to cytoplasmic molecules. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:120–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slavi N, et al. Connexin 46 (cx46) gap junctions provide a pathway for the delivery of glutathione to the lens nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:32694–32702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plum A, et al. Unique and shared functions of different connexins in mice. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White TW. Unique and redundant connexin contributions to lens development. Science. 2002;295:319–320. doi: 10.1126/science.1067582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White TW. Nonredundant gap junction functions. News Physiol Sci. 2003;18:95–99. doi: 10.1152/nips.01430.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans WH, De Vuyst E, Leybaert L. The gap junction cellular internet: connexin hemichannels enter the signalling limelight. Biochem J. 2006;397:1–14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retamal MA, et al. Diseases associated with leaky hemichannels. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:267. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srinivas M, Verselis VK, White TW. Human diseases associated with connexin mutations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2018;1860:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilly E, Sellitto C, Milstone LM, White TW. Connexin channels in congenital skin disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;50:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laird DW. Syndromic and non-syndromic disease-linked Cx43 mutations. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1339–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, et al. Exome sequencing reveals mutation in GJA1 as a cause of keratoderma-hypotrichosis-leukonychia totalis syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:243–250. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basaran E, Yilmaz E, Alpsoy E, Yilmaz GG. Keratoderma, hypotrichosis and leukonychia totalis: a new syndrome? Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:636–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyden LM, et al. Dominant De Novo Mutations in GJA1 Cause Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis et Progressiva, without Features of Oculodentodigital Dysplasia. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1540–1547. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richard G, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in erythrokeratodermia variabilis: novel mutations in the connexin gene GJB4 (Cx30.3) and genotype-phenotype correlations. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:601–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishida-Yamamoto A. Erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva. J Dermatol. 2016;43:280–285. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umegaki-Arao N, et al. Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus with a Postzygotic GJA1 Mutation Is a Mosaic Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis et Progressiva. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:967–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman J, Mehregan AH. Inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:385–389. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1971.04000220043008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia IE, et al. From Hyperactive Connexin26 Hemichannels to Impairments in Epidermal Calcium Gradient and Permeability Barrier in the Keratitis-Ichthyosis-Deafness Syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JR, White TW. Connexin-26 mutations in deafness and skin disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e35. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly JJ, Simek J, Laird DW. Mechanisms linking connexin mutations to human diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360:701–721. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delmar, M. et al. Connexins and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 10.1101/cshperspect.a029348 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Shuja Z, Li L, Gupta S, Mese G, White TW. Connexin26 Mutations Causing Palmoplantar Keratoderma and Deafness Interact with Connexin43, Modifying Gap Junction and Hemichannel Properties. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:225–235. doi: 10.1038/JID.2015.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerido DA, DeRosa AM, Richard G, White TW. Aberrant hemichannel properties of Cx26 mutations causing skin disease and deafness. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C337–345. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00626.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia IE, et al. Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome-associated cx26 mutants produce nonfunctional gap junctions but hyperactive hemichannels when co-expressed with wild type cx43. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1338–1347. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery JR, White TW, Martin BL, Turner ML, Holland SM. A novel connexin 26 gene mutation associated with features of the keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome and the follicular occlusion triad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essenfelder GM, et al. Connexin30 mutations responsible for hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia cause abnormal hemichannel activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1703–1714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chi J, et al. Pathogenic connexin-31 forms constitutively active hemichannels to promote necrotic cell death. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bukauskas FF, Bukauskiene A, Bennett MV, Verselis VK. Gating properties of gap junction channels assembled from connexin43 and connexin43 fused with green fluorescent protein. Biophys J. 2001;81:137–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White TW, Bruzzone R, Wolfram S, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Selective interactions among the multiple connexin proteins expressed in the vertebrate lens: the second extracellular domain is a determinant of compatibility between connexins. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:879–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valiunas V, Gemel J, Brink PR, Beyer EC. Gap junction channels formed by coexpressed connexin40 and connexin43. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1675–1689. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL. Expression of chimeric connexins reveals new properties of the formation and gating behavior of gap junction channels. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 4):955–967. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrio LC, et al. Gap junctions formed by connexins 26 and 32 alone and in combination are differently affected by applied voltage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8410–8414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruzzone R, Haefliger JA, Gimlich RL, Paul DL. Connexin40, a component of gap junctions in vascular endothelium, is restricted in its ability to interact with other connexins. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:7–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eskandari S, Zampighi GA, Leung DW, Wright EM, Loo DD. Inhibition of gap junction hemichannels by chloride channel blockers. J Membr Biol. 2002;185:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen DB, et al. Activation, permeability, and inhibition of astrocytic and neuronal large pore (hemi)channels. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26058–26073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.582155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mhaske PV, et al. The human Cx26-D50A and Cx26-A88V mutations causing keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome display increased hemichannel activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C1150–1158. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00374.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White TW, Gao Y, Li L, Sellitto C, Srinivas M. Optimal lens epithelial cell proliferation is dependent on the connexin isoform providing gap junctional coupling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5630–5637. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elenes S, Martinez AD, Delmar M, Beyer EC, Moreno AP. Heterotypic docking of Cx43 and Cx45 connexons blocks fast voltage gating of Cx43. Biophys J. 2001;81:1406–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75796-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fishman GI, Moreno AP, Spray DC, Leinwand LA. Functional analysis of human cardiac gap junction channel mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3525–3529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen DB, Braunstein TH, Nielsen MS, MacAulay N. Distinct permeation profiles of the connexin 30 and 43 hemichannels. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valiunas V. Cyclic nucleotide permeability through unopposed connexin hemichannels. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:75. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White TW, et al. Functional characteristics of skate connexin35, a member of the gamma subfamily of connexins expressed in the vertebrate retina. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1883–1890. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang J, et al. Connexin 43 hemichannels are permeable to ATP. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4702–4711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Contreras JE, Saez JC, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MV. Gating and regulation of connexin 43 (Cx43) hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11388–11393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1434298100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang N, et al. Connexin mimetic peptides inhibit Cx43 hemichannel opening triggered by voltage and intracellular Ca2+ elevation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:304. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butterweck A, Elfgang C, Willecke K, Traub O. Differential expression of the gap junction proteins connexin45, −43, −40, −31, and −26 in mouse skin. Eur J Cell Biol. 1994;65:152–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamibayashi Y, Oyamada M, Oyamada Y, Mori M. Expression of gap junction proteins connexin 26 and 43 is modulated during differentiation of keratinocytes in newborn mouse epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:773–778. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paznekas WA, et al. Connexin 43 (GJA1) mutations cause the pleiotropic phenotype of oculodentodigital dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:408–418. doi: 10.1086/346090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kogame T, et al. Palmoplantar keratosis in oculodentodigital dysplasia with a GJA1 point mutation out of the C-terminal region of connexin 43. J Dermatol. 2014;41:1095–1097. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee JR, Derosa AM, White TW. Connexin mutations causing skin disease and deafness increase hemichannel activity and cell death when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:870–878. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner DL, Weintraub H. Expression of achaete-scute homolog 3 in Xenopus embryos converts ectodermal cells to a neural fate. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1434–1447. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horton RM, Cai ZL, Ho SN, Pease LR. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques. 1990;8:528–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spray DC, Harris AL, Bennett MV. Equilibrium properties of a voltage-dependent junctional conductance. J Gen Physiol. 1981;77:77–93. doi: 10.1085/jgp.77.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinivas M, Hopperstad MG, Spray DC. Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10942–10947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191206198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White TW, Bruzzone R, Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Mouse Cx50, a functional member of the connexin family of gap junction proteins, is the lens fiber protein MP70. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:711–720. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mese G, et al. The Cx26-G45E mutation displays increased hemichannel activity in a mouse model of the lethal form of keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4776–4786. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.