Abstract

Sterile alpha motif (SAM) domains are protein interaction modules that are involved in a diverse range of biological functions such as transcriptional and translational regulation, cellular signalling, and regulation of developmental processes. SH3 domain-containing protein expressed in lymphocytes 1 (SLy1) is involved in immune regulation and contains a SAM domain of unknown function. In this report, the structure of the SLy1 SAM domain was solved and revealed that this SAM domain forms a symmetric homodimer through a novel interface. The interface consists primarily of the two long C-terminal helices, α5 and α5′, of the domains packing against each other. The dimerization is characterized by a dissociation constant in the lower micromolar range. A SLy1 SAM domain construct with an extended N-terminus containing five additional amino acids of the SLy1 sequence further increases the stability of the homodimer, making the SLy1 SAM dimer two orders of magnitude more stable than previously studied SAM homodimers, suggesting that the SLy1 SAM dimerization is of functional significance. The SLy1 SAM homodimer contains an exposed mid-loop surface on each monomer, which may provide a scaffold for mediating interactions with other SAM domain-containing proteins via a typical mid-loop–end-helix interface.

Introduction

The multifunctional adaptor protein SLy1 (SH3 domain-containing protein expressed in lymphocytes 1), also known as SASH3 (SAM and SH3 domain containing protein 3), is exclusively expressed in lymphocytes and plays different roles in various lymphocyte subsets1,2. SLy1 is important for T and B cell development and proliferation, and for complete activation of adaptive immunity3–5. In natural killer (NK) cells, SLy1 acts as a ribosomal support protein facilitating ribosomal stability and in turn viability and activation of mature, peripheral NK cells6. Lack of SLy1 compromises NK-mediated immunosurveillance, reduces cytotoxicity toward malignant and non-malignant NK cell targets, and increases cancer susceptibility6. In T and B cells SLy1 is located in the cytoplasm and nucleus1,3.

SLy1 is 380 amino acids in length and contains a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS), a Src homology 3 (SH3) and a sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain (Supplementary Fig. S1), which makes SLy1 a prototypical adaptor protein. Murine and human SLy1 show 94% sequence identity, and the amino acid sequence of the SAM domain is identical in both proteins1. Both SH37 and SAM8,9 domains have been shown to mediate protein-protein interactions in other proteins9–11. However, the specific functional roles of the SLy1 SAM and SH3 domains remain unresolved. SAM domains contain ~70 amino acids and share a common structural motif of five helices8,9. They are found in a multitude of proteins in organisms ranging from yeast to mammals and are involved in diverse biological functions including transcriptional and translational regulation, cellular signalling, and regulation of developmental processes9. SAM domains connect proteins to other proteins via SAM domains or non-SAM interaction motifs (e.g., PDZ and SH2 domains). A subclass of SAM domains specifically binds RNA12 and function as an RNA recognition element13. In addition, particular SAM domains bind to lipid membranes14,15.

Many SAM domains self-associate to form homodimers16–18, closed oligomeric structures19 or extended polymers20,21. Published equilibrium dissociation constants for SAM homodimers range between 0.5 and 5 mM for Ste11 SAM18 and EphA2 SAM16, indicating weak affinity. Homopolymeric SAM structures with demonstrated biological relevance form left-handed helices with six SAM monomers per turn21. Neighbouring monomers join in a head-to-tail fashion utilizing two opposite interfaces on the compact monomer structure referred to as end-helix (EH) and mid-loop (ML) surfaces20. The stability of the fibrils depends on the affinity of the interacting EH and ML surfaces. Experimentally determined equilibrium dissociation constants for this interaction range from 1.7 nM for TEL-SAM fibrils20 to 11 µM for Yan SAM fibrils22. SAM domains can also specifically bind to other SAM domains to form heterodimers22,23 or heterooligomers24. Examples with dissociation constants in the low micromolar range have been reported for the heterodimers of Odin SAM1/Arap3 SAM25, Odin SAM1/EphA2 SAM26 and Ship2 SAM/EphA2 SAM27. Other pairs like Mae SAM/Yan SAM22 or CNK SAM/Hyp SAM23 show nanomolar affinity.

Self-association also plays a role in cellular signal transduction. The function of a number of adapter proteins involved in signalling like Grb2 (growth factor receptor binder 2) and 14-3-3 proteins relies on dimerization28,29. Moreover, immune adapter SLP-76 (Src homology 2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa) self-association in response to T-cell receptor ligation is mediated by its N-terminal SAM domain30. We hypothesize that dimerization of SLy1 is required for its biological function and that the SAM domain plays a role in this process.

In the current report, we show that the SAM domain of SLy1 self-associates to form a distinct dimer with an affinity much stronger than reported previously for homodimerization of other SAM domains. Structure determination reveals that this SAM domain forms a novel type of dimer interface that is incompatible with homooligomerization. The stability of the homodimer is sensitive to the presence of amino acids flanking the SAM domain. Our findings on SLy1 SAM self-association suggest that SLy1 functions as a dimer.

Results

Three SLy1 SAM domain constructs were produced successfully in E.coli as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins, released by PreScission cleavage, and purified to homogeneity. The first variant is referred to as SAMwt and contains the SAM domain (P254–Y316), the five residues D317-E321 succeeding it in SLy1, and an N-terminal glycine from the tag (Supplementary Fig. S2). SAMC differs from SAMwt by an S320C amino acid exchange, which is located outside the predicted SAM domain. The slightly longer SAMlg comprises residues G249-E321 of SLy1 preceded by a glycine-proline tag. Typical yields of the purified SAM variants were 5–8 mg per litre of culture medium.

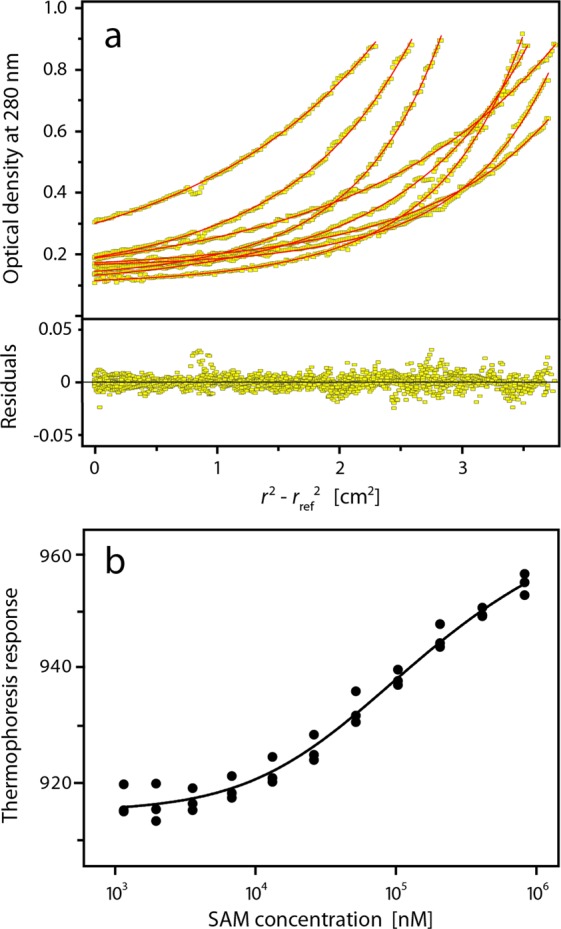

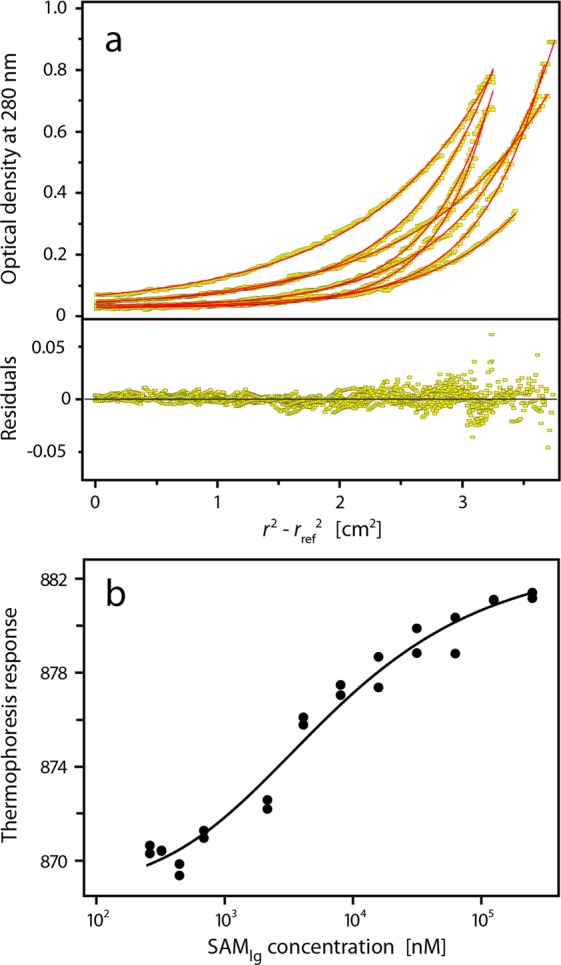

The SLy1 SAM domain exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium

The calculated molecular mass of SAMwt is 7,929 Da. Size exclusion chromatography used in the purification of SAMwt indicated that this protein oligomerizes, which was also supported by blue native PAGE experiments showing that SAMwt is monomeric at two digit micromolar concentrations but monomer and a minor dimer fraction is observed at a gel loading concentration of 210 µM (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed to characterize the SAM domain oligomerization in detail. An acceptable global fit of the data was achieved only with the monomer-dimer equilibrium model with low residuals throughout the radial concentration profile (Fig. 1a). The global fit of the sedimentation profiles resulted in a Ka = 8.5 (2.4, 30) × 103 M−1, i.e., Kd = 117 (33, 423) µM, and a molecular mass of (8,040 ± 532) Da for the SAMwt monomer. The numbers in parenthesis specify the 95% confidence interval. Both the one-component and the two-component models provided inferior fits with significantly larger residuals than the monomer-dimer equilibrium model. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) was used as an orthogonal method to measure the binding affinity of the SAM domain self-association (Fig. 1b). The experimental thermophoresis response curves could be fitted with a monomer-dimer equilibrium model, providing a dimer dissociation constant of Kd = (153 ± 25) μM.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the SLy1 SAMwt monomer-dimer equilibrium. (a) Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed using samples with different SAMwt concentrations (60, 120, and 300 µM) at different speeds. Data were fit globally with a monomer-dimer model. The upper panel shows concentration profiles recorded after establishment of equilibrium between sedimentation and back diffusion and the calculated concentration distributions (red lines) based on a monomer-dimer equilibrium model. The global fit gives a Kd = 117 (33, 423) μM. The lower panel shows the residuals of the fit. (b) Binding isotherm from microscale thermophoresis data. The thermophoresis response of fluorescent labelled SAMwt is dependent on the total concentration of SAMwt. The experimental data were fit to a monomer-dimer equilibrium model (solid line) with a Kd of (153 ± 25) μM.

Cross-linking the SAMC monomers quenches chemical exchange

Variation in the intensity and line-widths of resonances in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMwt indicated the presence of chemical exchange, presumably because of the monomer-dimer equilibrium. 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired at different SAMwt concentrations. Overlay of the spectra showed that the chemical shift of resonances changed and the line widths of particular resonances showed strong line-broadening because of intermediate-to-fast exchange on the μs-ms timescale (Supplementary Fig. S4). Initial attempts to determine the three-dimensional (3D) structure of SAMwt by NMR spectroscopy were unsuccessful because the chemical exchange prohibited the collection of reliable interproton distance restraints. In particular, the heteronuclear filtered NOESY data, which provide intermolecular distance restraints, suffered from a very low signal-to-noise ratio and showed only a limited number of cross correlations (Supplementary Fig. S5). The introduction of an intermonomer disulphide bond stabilized the native dimer state and eliminated the chemical exchange process, thereby facilitating structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. This was achieved by exchanging S320, which is located C-terminal to the predicted SAM domain, with cysteine, to give SAMC. 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of SAMC in the reduced and oxidized state were similar, indicating that disulphide bond formation did not perturb the overall fold of the SAM domain (Supplementary Fig. S6). Weighted chemical shift mapping between SAMwt and reduced-state SAMC showed that the S320C exchange caused negligible chemical shift changes with only pronounced changes observed around the mutation site (Supplementary Fig. S7). In addition, the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the disulphide-bonded SAMC was also similar to the SAMwt spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S7) with chemical shift differences for resonances of residues around the mutation site and a few larger than average chemical shift changes for resonances corresponding to residues further away from the S320C exchange, which are due to reduced mobility of the C-terminus and the difference in dimer population.

NMR structure of the SAMC homodimer reveals a new interface

Two- and three-dimensional NMR spectra of the cross-linked SAMC dimer are well-resolved and show a single set of resonances corresponding to the amino acid sequence of the monomer, thus indicating a symmetric homodimer31–33. Near complete (97%) assignment of SAMc resonances was achieved (Supplementary Table S8). A total of 5,026 partially assigned NOESY cross peaks were obtained from the five 3D NOESY spectra recorded. This number includes 286 cross peaks from the two double isotope-filtered NOESY spectra that provide intermonomer cross correlations exclusively. Fifty-eight backbone ϕ/ψ torsion angle pairs were derived from the chemical shift data using TALOS+34. In addition, 16 experimentally determined backbone H-bonds were used as restraints. Sidechain χ1 torsion angles of 24 residues were restrained to one of the staggered conformations (60°, 180°, −60°) ± 30° as determined by combined 3JHαHβ and 3JNHβ couplings analysis. Iterative NOESY data analysis and structure calculation by ARIA35,36 extracted 2,466 unambiguously assigned and 1,593 ambiguous distance restraints from the NOESY data (Supplementary Table S8). Among the uniquely defined restraints are 236 intermonomer and 406 long-range intramonomer distances.

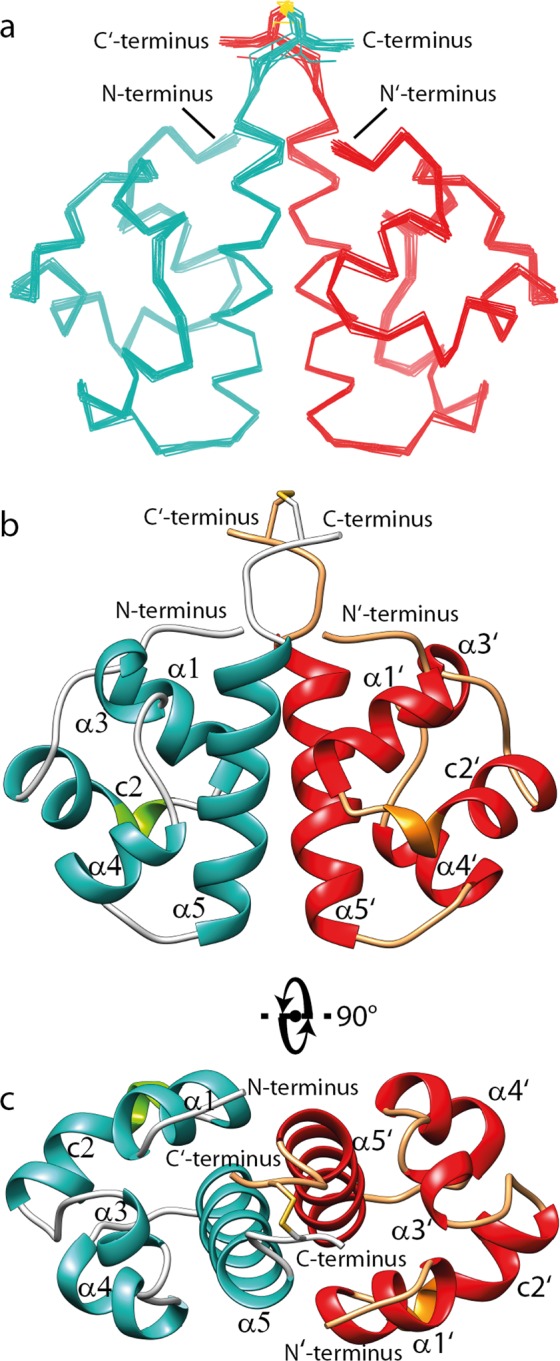

Superposition of the final 15 lowest energy models of the SAMC homodimer refined in an explicit water shell is shown in Fig. 2a. The coordinate root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) is 0.31 Å for the backbone heavy atoms and 0.57 Å for all heavy atoms. Structural statistics are presented in Supplementary Table S8. RPF analysis indicates excellent agreement between the experimental NOESY data and the calculated NMR structure of the SAMC homodimer, and the high DP-score shows that the amount of data defines the structure accurately37. Superposition of the two monomers of any of the 15 SAMc homodimer models yields a pairwise Cα r.m.s.d. of no more than 0.01 Å in line with a symmetric homodimer.

Figure 2.

NMR solution structure of SLy1 SAMC homodimer. (a) Superposition of the 15 lowest energy structures of the disulphide bond-stabilized homodimer of SAMC. The backbones of the monomers are coloured teal and red. (b,c) Ribbon representation of the structure closest to the average backbone structure (r.m.s.d. = 0.19 Å) of the ensemble. α-helices are shown in teal and red in each monomer, whereas the 310-helix part in the composite helix c2 is shown in green and orange. Helices α5 and α5′ are in tight contact to form the major part of the interface. They run in a parallel fashion with an angle of ~−50° between their long axes. Helix α1 and the N-terminus of one monomer are in close proximity to the C-terminal region of helix α5′ of the opposing monomer, and also form part of the dimer interface.

Each monomer in the NMR structure shows the typical five helix bundle of the canonical SAM domain fold (Fig. 2b,c)38. DSSP39,40 analysis of the SAMC atomic coordinates suggested an H-bond pattern in agreement with four α-helices: α1 (L257–I264), α3 (L281–F284), α4 (E289–L295) and α5 (P300–D315). In addition, a kinked composite helix c2 (E267-L275) was identified consisting of a 310-helix (E267–H269) and an α-helical segment (T270–L275).

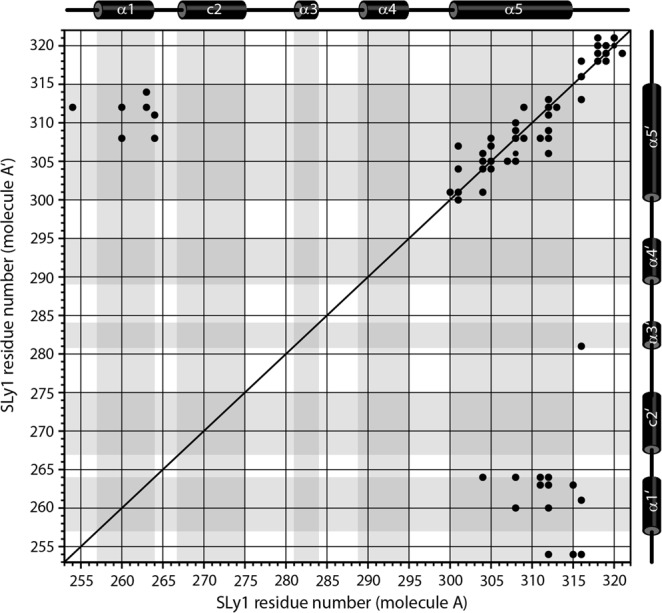

The unique feature of the SLy1 SAMC symmetric homodimer is the dimer interface, which has not been observed previously for SAM domains. This interface buries ~1,200 Å2 surface area. Most direct information on the interface can be derived from intermonomer proton-proton distances detected in isotope-filtered 3D NOESY experiments. The contact map in Fig. 3 provides insight into the architecture of the dimer interface. The majority of intermonomer contacts is formed between protons in the long helix α5 and the symmetrical partner helix α5′. Additional contacts are found between protons located in the C-terminal halves of helices α1 and α5′, respectively. The third group of short intermonomer contacts is found between protons in the C-termini of both monomers. In addition, NOE cross peaks were observed between the N-terminal P254 and the C-terminal end of helix α5′, and between the C-terminal Y316 in one monomer and L261 in helix α1′ as well as L281 in helix α3′ of the other monomer. In accordance with the intermonomer NOE data, the NMR structure shows that the SAMc monomers face each other with the two α5 helices running in the same direction with additional contributions from α1 and the N-terminus (Fig. 2). The angle between the two helix axes of α5 and α5′ is ~−50°. The N-terminus and helix α1 are nearly perpendicular to helix α5 of the same monomer, and the side chains of residues in these three elements interact with side chains of the opposing helix α5′ in the other monomer.

Figure 3.

Intermonomer contact pattern in the SLy1 SAMC homodimer. Intermonomer NOE cross correlations (•) in the (13C, 15N) isotope-filtered, 15N- or 13C-edited NOESY spectra from residues in molecule A to residues in molecule A’ Schematic representation of the secondary structure of the SAMC domain is presented above and on the right side of the plot. Shading in the plot defines secondary structure regions.

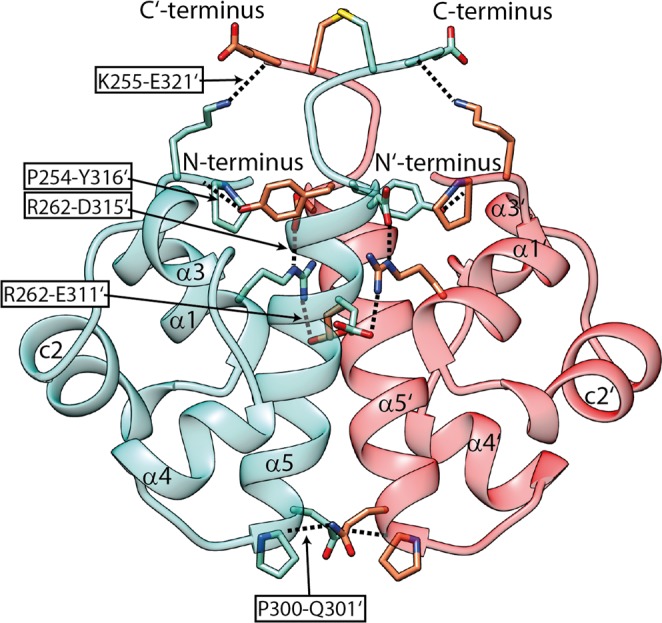

The interacting surfaces of the two monomers display matching hydrophobic regions and charge complementarity in the SAMC dimer (Fig. 4). Hydrophobic side chains of helix α5 extend into the hydrophobic groove formed by helices α1′, c2′ and α5′ of the other monomer. Analysis of the atomic coordinates of the dimer structure identified 12 potential intermonomer hydrogen bonds and salt bridges that stabilize the dimer (Fig. 5 & Supplementary Table S9). In particular, a network of such non-covalent interactions is suggested between residues in the N-terminus (P254, K255) or in helix α1 (R262) of one monomer with residues in the C′-terminus (Y316, E321) and in the C-terminal halve of helix α5′ (E311, D315) of the second monomer. A hydrogen bond between P300 of helix α5 and Q301 of helix α5′ is present and likely pulls the two helices together at their N-termini. The stabilizing disulphide bond between cysteines in position 320 adopts a negative right handed staple (−RHStaple) conformation41 in 14 out of the 15 analysed structures and a negative left handed staple (−LHStaple) conformation in one model.

Figure 4.

Surface complementarity of the SAMC monomer. (a) Ribbon and (b) surface representation of the NMR structure of the SAMC monomer are displayed in identical orientation. Surface colouring is based on electrostatic potential at pH 6.4 with negative charges in red and positive charges in blue. Helix α5 forms a hydrophobic ridge with negative charges on the left and hydrophobic residues on the right side. A positively charged ridge formed mainly by side chains of helices α1 and c2 exists. There is a hydrophobic groove between the two ridges. (c) Helix α5′ of the second monomer fits into this hydrophobic groove and side chains E311 and D315 of helix α5′ form salt bridges with residues that are part of the positively charged ridge.

Figure 5.

SLy1 SAMC homodimer interface is stabilized by hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. H-bonds and salt bridges between the two monomers of the SAMC homodimer shown in teal and red are labelled. Details on the stabilizing bonds are given in Supplementary Table S9. Side chains of interacting amino acids are shown in stick representation in the ribbon representation of the NMR structure.

Crystal structure of SAMwt

In parallel, we determined the crystal structure of SAMwt to a resolution of 2.05 Å. The structure belongs to the tetragonal space group P 41 21 2 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. Details on data and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table S10. The final structure comprised 65 of the expected 69 residues (P254–D317 plus the N-terminal glycine). No electron density was visible for T318–E321 in the weighted 2Fo-Fc map, most likely because of conformational flexibility at the termini. The 3D-structure adopts the typical five helix bundle of a SAM domain with the following secondary structure elements: α1 (L257–R263), α3 (L281–F284), α4 (E289–E294) and α5 (P300–Y316). In addition, a composite helix c2 (E267–L274) was identified consisting of a 310-helix (E267–H269) and an α-helical segment (T270–L274).

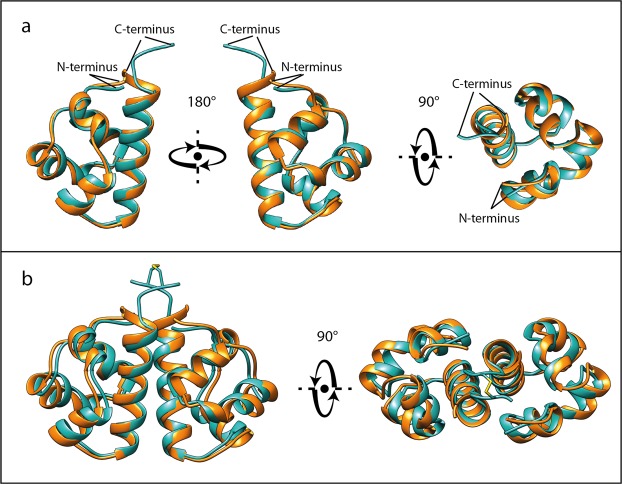

The crystal structure of SAMwt and the NMR structure of SAMc share the same architecture

The average NMR structure of the SAMC monomer and the X-ray structure of SAMwt are almost identical (Fig. 6a) with a Cα r.m.s.d. between the two monomers of 0.84 Å. The composite helix c2 is observed in both structures. The length of four helices differs slightly between the two structures: helices α1, c2, and α4 are one residue shorter in the X-ray structure (I264, L275, and L295, respectively) while α5 is one residue longer (up to Y316), according to DSSP analysis.

Figure 6.

Overlay of SAMC NMR and SAMwt X-ray structures. The SAMC structure closest to the average backbone structure of the ensemble of NMR structures of SAMC (teal) and the X-ray structure of SAMwt (orange) are depicted. (a) Superposition of SLy1 SAM monomers (Cα r.m.s.d. = 0.84 Å) is shown. (b) The superposition of the SAMC homodimer with the crystallographic dimer of SAMwt shows nearly identical structures with a Cα r.m.s.d. of 1.13 Å for the dimer.

Although the asymmetric unit contained only a single molecule, inspection of symmetry related molecules in crystallographic complexes can reveal the presence of a multimeric state with sufficiently high dissociation free energies to form stable macromolecular assemblies. The PISA web server was used to calculate possible multimeric states, accessible/buried surface area, and the free energy of dissociation. The highest dissociation free energy was obtained for a crystallographic dimer with 2-fold crystallographic symmetry in which helices α5 and α5′ point in the same direction and are located in close proximity to each other. A free energy gain of 4.7 kcal mol−1 and a buried surface area of ~870 Å2 upon SAMwt symmetric dimer formation were obtained. The lower buried surface area (difference of ~330 Å2) when compared with that of the NMR structure arises from the four residue shorter C-terminus in the SAMwt crystal structure.

Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between amino acids in helices α1 and α5′ and between P300 and Q301 at the N-terminus of helices α5 and α5′, respectively, stabilize the dimer interface. A list of all hydrogen bonds and salt bridges in the crystallographic SAMwt dimer is presented in Supplementary Table S9. Equivalent H-bonds and salt bridges are seen in the NMR structure of SAMC. Superposition of the NMR structure of the SAMC homodimer with the crystallographic SAMwt homodimer confirms a high global identity with a Cα r.m.s.d. of 1.13 Å (calculated with LSQMAN42) (Fig. 6b).

Extension of the N-terminus of SAMwt increases the stability of the homodimer

The SAMC structure presented in Fig. 4c shows a group of surface-exposed negatively charged residues (D317, E321) in the C-terminal area. The N- and C-termini of adjacent SAMC monomers are in close spatial proximity (Figs 2c and 4c) and SLy1 has a high density of positive charges (K250, R251, K253, K255) in the sequence preceding the SAM core domain (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, we hypothesize that these residues form electrostatic interactions that further increase the affinity of SAM homodimerization. In order to test this, an N-terminally extended SLy1 SAM domain construct (SAMlg) was produced (Supplementary Fig. S2). Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) and MST experiments were used to examine the self-association of SAMlg. The analysis of the data revealed that the SAMlg undergoes a monomer-dimer equilibrium with a stronger affinity reflected by the Kd values of 2.2 (1.8, 2.6) µM and (5.4 ± 1.4) µM obtained by AUC and MST, respectively (Fig. 7). Comparison with the dissociation data for SAMwt (Supplementary Table S11) reveals that the extended SAMlg shows an affinity increase by a factor of 30 to 50.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the monomer-dimer equilibrium of SAMlg. (a) Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed using samples with different SAMlg concentrations (31, 64, and 98 µM) at multiple speeds. Data were fit globally with a monomer-dimer model. The upper panel shows concentration profiles recorded after establishment of equilibrium between sedimentation and back diffusion and the calculated concentration distributions (red lines) based on a monomer-dimer equilibrium model. The global fit gives a Kd = 2.2 (1.8, 2.6) μM. The lower panel shows the residuals of the fit. (b) Binding isotherm from microscale thermophoresis data. The fit of the experimental data to a monomer-dimer equilibrium model (solid line) yields a Kd of (5.4 ± 1.4) μM.

Translational diffusion coefficients (D) of SAMlg particles at 30 °C were determined by NMR spectroscopy to complement the AUC and MST data. Linear regression of the diffusion coefficients measured at three concentrations (0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM) to zero concentration provided the diffusion coefficient at infinite dilution (D0). Based on the model of spherical particles, the hydrodynamic radius Rh with a value of (20.6 ± 0.5) Å was calculated. Wilkins et al. established an empirical relation Rh = 4.75 N0.29 Å between the hydrodynamic radius and the number of residues in the polypeptide chain, N, for natively folded proteins43. Applying this relation to SAMlg (N = 75) predicts Rh = 16.6 Å for monomers and 20.3 Å for dimers. Thus, the diffusion data support the hypothesis of a predominantly dimeric oligomerization state of SAMlg in the protein concentration range from 0.1 to 1 mM. This agrees well with the Kd results where over the concentration range of 0.1–1 mM the calculated fraction of SAMlg in the dimer state is 85–95%.

Discussion

In the present study, complementary biophysical and structural techniques were combined to characterise the self-association behaviour of the SLy1 SAM domain. SAMwt exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium with a Kd of 117 μM as determined by AUC, which was supported by MST results. Dimerization was also confirmed for SAMlg by AUC, MST and NMR-based diffusion measurements.

Stabilization of the SAMC homodimer by a disulphide bond outside the predicted core domain enabled structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. Similar strategies have been used successfully in NMR structural studies of homo-32 and heterodimers44 where disulphide bonds have been introduced to quench chemical exchange processes that have hampered NMR investigations. The introduction of the disulphide bond into the SAM homodimer yielded almost identical resonance positions in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of SAMC in the reduced and oxidized state, indicating that the disulphide bond did not perturb the homodimer structure (Supplementary Fig. S6). Nonetheless, comparison of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of SAMwt and disulphide-bonded SAMC homodimer revealed larger than average chemical shift differences for some resonances from the N-terminal region (K255, T256), the second half of α-helix 5 (L313, L314, D315) and from C-terminal residues close to the S320C mutation site (Supplementary Fig. S7). These observed chemical shift differences arise (besides the local differences caused by the S320C exchange) predominantly from the SAMwt existing in the monomer-dimer equilibrium, where the population of monomer is ~17% at the NMR sample concentration of 1.4 mM. Therefore, the chemical shift of resonances in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of SAMwt is affected by this monomer population. In addition, the reduced mobility of the C-terminus of cross-linked SAMC will limit sampling of conformational space and thus influence the chemical shift of resonances associated with these terminal residues.

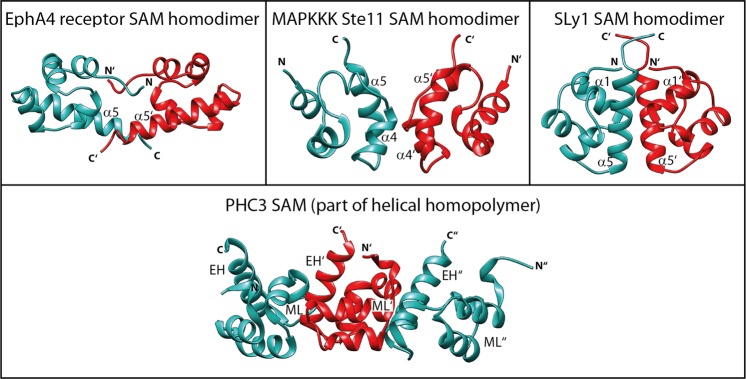

The structure of the SLy1 SAM domain dimer was solved by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Since only one SAMwt molecule was found in the asymmetric unit of the crystal structure possible SAM assemblies and interfaces were determined from the analysis of the symmetric equivalent SAMwt molecules using PISA. The only energetically favourable SAMwt dimer interface is in agreement with the intermonomer NOE data recorded. The crystallographic homodimer closely matches the SAMC solution structure with a low Cα r.m.s.d. of 1.13 Å. In both cases, the two SLy1 SAM domains predominantly interact through their helices α5 with the long sides of the helices packing against each other, and additional contributions from helix α1, c2 and the N-terminal residues (Fig. 6b). Future mutational studies can build on our structural data and should help to demarcate the role of key residues required for SLy1 SAM homodimerization. SAM domains frequently self-associate; however, symmetric homodimerization of SAM domains is uncommon. Currently, structures of only two SAM homodimers have been deposited in the PDB16,17, whereas other forms of SAM domain homo- and heterooligomers are mediated by the asymmetric EH-ML interface (cf. Fig. 8, lower panel). In both reported SAM homodimers, the dimer interface differs from the interface observed in the SLy1 SAM homodimer (Fig. 8). A symmetric homodimer was observed in the crystal structure of the isolated EphA4 SAM domain (PDB ID: 1B0X)16. N- and C-terminal ends of the EphA4 SAM monomer structure including the C-terminal part of the long helix α5 point away from the core structure of the SAM domain and interdigitate with the termini of the other monomer (Fig. 8). The antiparallel termini represent the major interface between the EphA4 SAM monomers with additional interactions from side chains of helices α1 and α316. The other reported SAM homodimer was determined by NMR spectroscopy for the SAM domain of the yeast protein Ste11 (PDB ID: 1X9X)17. The interface between the Ste11 SAM monomers is formed by the N-terminal half of helix α5 that is packed against the parallel running helix α4′ of the other monomer (Fig. 8). These two SAM homodimers show low stability in solution, as indicated by dissociation constants in the single digit millimolar range (Supplementary Table S11)16,18, which is ~4 to 40-fold weaker than the corresponding affinity measured for the SLy1 SAMwt homodimer. Inspection of the three SAM homodimer structures reveals that the buried surface area of the SLy1 SAMwt homodimer (870 Å2) is larger than that of the Ste11 homodimer (504 Å2) but moderately lower than that of the EphA4 SAM homodimer (1,009 Å2). Although the EphA4 SAM homodimer has a buried surface area of similar size to that of the SLy1 SAM homodimer, the number of stabilizing hydrogen bonds and salt-bridges is noticeably lower (2 versus 12), which likely explains the observed difference in homodimer stability. In contrast, for the Ste11 homodimer a similar number of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are present (8), but the buried surface area is considerably smaller and thus the homodimer is less stable.

Figure 8.

SAM domain interfaces in homodimers and homopolymers. Identical surfaces of two SAM monomers form the interface of symmetric SAM homodimers. The upper row shows the three types of SAM homodimers that have been reported. The termini-mediated EphA4 receptor SAM homodimer (PDB: 1B0X)16, the MAPKKK Ste11 SAM homodimer stabilized by interactions between amino acid residues in helices α4 and α5 (PDB: 1X9X)17, and the SLy1 SAM homodimer stabilized by interactions between amino acid residues in helices α1, α5 and the termini of both monomers (PDB: 6G8O). The monomer-monomer interface in a SAM homopolymer is formed by two different surfaces: the mid-loop (ML) surface of one monomer and the end-helix (EH) surface of the other monomer. This feature enables oligomerization. Three PHC3 SAM monomers that belong to a left-handed helical structure with six monomers per turn (PDB: 4PZO)75 are displayed in the lower panel.

The close proximity of the N- and C-termini of SAMC coupled with their complementing charges (i.e., D317 and E321 at the C-terminus and K250, R251, K253 and K255 at the N-terminus) suggests further dimer stabilizing interactions between SLy1 proteins involving residues that are not part of the SAM domain. This is supported by the observed strong influence of SLy1 residues G249−K253 on dimer stability (Fig. 7). Extension of the SAMwt N-terminus by these five residues increased the affinity of the SAM domain dimerization by a factor of 30−50. The Kd of SAMlg is therefore comparable to the Kd observed for SAM domain homo- and hetero-associations, for which biological relevance has been ascertained (e.g., Yan SAM fibrils22 or the heterodimers of Odin SAM1/Arap3 SAM25, Odin SAM1/EphA2 SAM26 and Ship2 SAM/EphA2 SAM27), suggesting that the SLy1 SAM dimerization is of functional significance for SLy1. Self-association is not uncommon for adapter proteins and proteins involved in cell signalling. 14–3–3 proteins have been identified as binding partners of SLy15. Interestingly, 14-3-3 proteins function as dimers and have been shown to interact with other dimeric proteins. Thus, SLy1 may interact as a dimer with 14-3-3 proteins.

Besides the SAM domain of Ste11 forming a homodimer, this domain also interacts with the SAM domain of the Ste11 regulator Ste50 through its ML surface, forming a distinct heterodimer through a ML-EH interaction. Since the structure of the SLy1 SAM homodimer contains an exposed ML surface on each monomer, it is plausible that other SAM domain-containing proteins could interact with SLy1 SAM in its dimerized state via an ML-EH interaction, thereby enabling SLy1 to mediate interactions between other SAM domain-containing proteins. Consequently, modulation of the SLy1 SAM domain dimerization would affect the type of protein-protein interactions mediated by SLy1. Two putative phosphorylation sites in SLy1, T318 and S320, are in close proximity to the SAM homodimer interface45. Currently, no biological function has been assigned to these phosphorylation sites. However, phosphorylation at either of the two residues would likely affect SAM dimerization kinetics and regulate dimerization, as has been shown for interface proximal phosphorylation sites in other proteins that dimerize46,47. Characterising the role phosphorylation has in modulating SAM dimer affinity and identifying binding partners to SLy1 SAM should further our understanding of the SLy1 interactome.

In conclusion, the SAM domain of the adapter protein SLy1 homodimerises through a novel interaction interface. This homodimer is significantly more stable than other reported SAM homodimers, especially in the presence of an extended N-terminus, suggesting that SLy1 functions as a dimer. Such dimerization provides a larger interaction surface for SLy1 to function as an adapter protein.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and recombinant protein production

The SAM domain of murine SLy1 (UniProtKB: Q8K352) comprises amino acid residues 254–316. A SLy1 SAM coding DNA fragment was cloned into a modified pGEX-6P-2 vector (GE Healthcare) with a unique Bsp120I restriction site using Bsp120I and XhoI. The complete gene product contains an N-terminal GST tag followed by a PreScission protease recognition sequence and residues 254 to 321 of SLy1. A longer version of the described plasmid contains DNA coding for residues 249 to 321 of SLy1. A third plasmid encodes residues 254–321 of SLy1 but with cysteine instead of serine at position 320 (Supplementary Fig. S2).

The fusion proteins were expressed in LB medium with 100 µg/mL ampicillin using Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with one of the prepared plasmids. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (PBS, 100 µg/mL lysozyme, 20 µg/mL DNAse A, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail Complete (Roche)), incubated at room temperature with gentle mixing for 1 h and mechanically disintegrated (Branson 250 rod sonifier (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT, USA) or microfluidizer M-110P (Microfluidics, Westwood, MA, USA)). Cell debris were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was applied to a Glutathione Sepharose affinity column, washed with 2 × 5 CV GST binding buffer (PBS, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.4) and 2 × 5 CV PreScission cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, pH 7). The slurry was incubated with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) at 10 °C under gentle agitation overnight. The SAM containing flow-through was concentrated using an Amicon stirred cell (50 mL, MWCO 3000), passed through a 0.2 µm syringe filter and fractionated on a size exclusion column (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 pg, GE Healthcare). The running buffer was 50 mM potassium phosphate, 20 mM NaCl, pH 6.4. Cysteine-containing SAM was purified under reducing conditions. Amino acid sequences of the three produced SLy1 SAM variants SAMwt, SAMC, and SAMlg are listed in Supplementary Fig. S2. Expression of uniformly labelled [U-15N] or [U-13C, 15N] protein was carried out in M9 minimal medium containing (15NH4)SO4 or both (15NH4)SO4 and 13C-glucose, respectively. Purity of the SAM constructs was confirmed by SDS PAGE. Biophysical studies were conducted in standard buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.03 wt% NaN3, pH 6.4) except for NMR experiments, where the standard buffer was supplemented with 7% 2H2O (referred to as NMR buffer).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed with Beckman Optima XL-A (SAMlg) and ProteomLab X-LA (SAMwt) ultracentrifuges (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) equipped with absorption optics. Protein samples (120 µl each) in standard buffer without NaN3 were loaded into standard aluminium double sector cells with quartz windows and an optical path length of 12 mm. The reference sector was filled with buffer. Centrifugation was performed at a temperature of 30 °C and different speeds using An-50 Ti Analytical 8-Place (SAMwt: 28,000; 35,300; and 42,700 rpm) and An-60 Ti Analytical 4-Place (SAMlg: 31,900; 39,000; 45,100; and 50,400 rpm) titanium rotors (Beckman-Coulter). Three samples with different loading concentrations (SAMwt: 60, 120, and 300 µM; SAMlg: 31, 64, and 98 µM) were analysed for each SAM variant. Sedimentation equilibrium profiles were recorded at 280 nm in radial step mode with a 10 µm (30 µm) step size and 20-point (5-point) averaging for SAMwt (SAMlg). Data evaluation was carried out using the global equilibrium fitting module of UltraScan II software (ver. 9.9) (http://www.ultrascan.uthscsa.edu). All sedimentation equilibrium profiles with sufficiently high information content were used in the global fits. Parameters required for data analysis were derived using the following tools (protein specific parameters are based on amino acid sequence): partial specific volume of the proteins and the mass density of the buffer were calculated with SEDNTERP (ver. 20120828 BETA; http://www.jphilo.mailway.com/download.htm#SEDNTERP). Monomer molecular mass and the molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm were estimated with ProtParam (http://expasy.org/tools/protparam.html). Absorbance profiles were converted into molar concentration profiles prior to global nonlinear least-squares fits of the equilibrium data to different interaction models. Three models were tested: (i) monomer-dimer equilibrium of reversibly self-associating species; (ii) single ideal species (one-component model); (iii) two ideal, non-interacting species (two-component model).

Microscale thermophoresis

A Monolith NT.015 device (NanoTemper Technologies GmbH, Munich, Germany) was used48. SAMwt and SAMlg were fluorescent labelled with the amine-reactive Alexa Fluor 488 dye (NT labelling kit BLUE). Dilution series of the proteins were prepared in standard buffer. The concentration of fluorescence labelled SAMwt (70 nM) or SAMlg (60 nM) and the total sample volume (10 μL) was kept constant within a dilution series. The total concentration of SAMwt was varied between 1.1 and 824 µM (SAMlg: 0.2 and 250 μM). For each sample, 5 μL of protein solution was transferred into a NT Premium Coated Capillary (SAMwt) or NT Standard Treated Capillary (SAMlg). The binding isotherm was recorded at room temperature. Experimental data were fitted to a monomer-dimer equilibrium.

NMR experiments

For structure determination, 1.4 mM [U-15N, 13C] or [U-15N] labelled SAMC in NMR buffer was used at 35 °C, unless otherwise noted. Data were recorded on Varian Unity Inova or VNMRS and Bruker Avance III HD NMR spectrometers equipped with cryogenically cooled z-gradient probes operating at 1H frequencies of 600, 700 and 900 MHz. Backbone, and aliphatic and aromatic side chain 1H, 15N and 13C resonance assignments for the SAMC homodimer were obtained from multidimensional heteronuclear NMR experiments. Proton chemical shifts were referenced to 2, 2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS), whereas the 15N and 13C chemical shifts were indirectly referenced according to the ratios given by Wishart et al.49. Data sets were processed using NMRPipe50 and analysed by CcpNMR Analysis51.

NMR-based structure calculations

Interproton distance restraints were derived from 3D NOESY-[1H-15N]-HSQC (mixing time τmix = 150 ms), NOESY-[1H-13C]-HSQC (aliphatic region, τmix = 120 ms), NOESY-[1H-13C]-HSQC (aromatic region, τmix = 140 ms) experiments on the [U-13C,15N] SAMC dimer. Intermonomer 1H-1H distances were provided by 3D ω1-(15N, 13C)-filtered NOESY-[1H-15N]-HSQC (τmix = 200 ms) and ω1-(15N, 13C)-filtered NOESY-[1H-13C]-HSQC (τmix = 150 ms)52. Samples for isotope-filtered experiments were prepared by mixing equimolar amounts of reduced isotope-labelled and unlabelled SAMC. Subsequently, the sample was placed under oxidizing conditions to facilitate disulphide bond formation. The final concentration of labelled protein in this sample was 0.8 mM.

Backbone ϕ and ψ angles were derived from experimental 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 15NH, 1HN, 1Hα chemical shifts using TALOS+34. Side chain χ1 torsion angles were deduced from experimental 3J coupling constants based on the empirical Karplus relation for χ1 using self-consistent Karplus parameters53. Quantitative 3JNHβ-HNHB and 3JHαHβ-HAHB(CACO)NH experiments were recorded to measure 3J couplings. Interresidue Ni-HN ∙∙∙∙ O = Cj′ hydrogen bonds were detected by the observation of h3JNC′ couplings in a 2D long-range HNCO experiment54.

Version 2.3.2 of ARIA (Ambiguous Restraints for Iterative Assignment) was used for NOESY cross peak assignment and structure calculation35,36. NOE cross peak assignments of the acquired NOESY spectra were obtained by an iterative procedure using a combination of manual and automatic steps. The tolerances for automatic assignments by ARIA were 0.04–0.05 and 0.04–0.06 ppm for the 1H direct and indirect dimensions, respectively, and 0.5 ppm for the heteronuclear dimensions. Experimentally detected H-bonds, experimental χ1 and TALOS derived ϕ and ψ torsion angles as structure restraints were also used. A homodimeric SAMC structure with C2 symmetry was explicitly assumed and the non-crystallographic symmetry option was active31,33. The disulphide bridge between C320 and C320′ was introduced as a covalent bond. Structures were calculated by a combination of ARIA and CNS v1.214255 (including the ARIA patchset) using the PARALLHDG force field with a log-harmonic potential56 and automatic restraint weighting. In the final iteration, 100 structures were calculated and refined in explicit water. The 15 lowest-energy SAMC structures were selected for further analysis.

The stereochemical quality of the refined models was assessed in PROCHECK NMR57. Agreement of the NOE data with the calculated structures was assessed using the RPF tool (http://nmr.cabm.rutgers.edu/rpf)37. Assignment of secondary structure elements (SSE) based on protein coordinates was performed by DSSP39,40. The webserver PDBeFold (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm/) was used for secondary structure based comparison and 3D alignment of SAM structures, referred to as secondary structure matching (SSM)58. The PISA webserver (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/) was used to analyse the SAMC homodimer and to derive potential contact-dependent and electrostatic interactions between the monomers from the atomic coordinates59.

X-ray crystallography

Purified SAMwt (~10 mg mL−1) was transferred into Tris buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0), sterilized by membrane filtration (0.2 µm) and used for crystallization by the vapour diffusion method. Crystals were grown in 1.4 µL sitting drops (0.7 µL protein solution and 0.7 µL reservoir solution) against a 70 µL reservoir (0.1 M K2HPO4, 2.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M imidazole). Crystals appeared after 5 to 7 days incubation at 19 °C. Crystals were cryoprotected by addition of 10% (v/v) glycerol, mounted in a fibre loop, flash cooled in a stream of cold (~100 K) nitrogen gas and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. X-ray diffraction data at 100 K were recorded at the beamline ID30A-3 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, using an Eiger X 4 M detector (DECTRIS, Baden-Dättwil, Switzerland).

Diffraction images were processed with the program XDS60 resulting in integrated intensities for all diffraction spots. The program POINTLESS61 was used for space group identification. Scaling of the diffraction images and averaging of symmetry-related reflections was conducted with the program AIMLESS62. The number of molecules in the crystallographic asymmetric unit was determined using the Matthews coefficient63 provided by the CCP4 software suite64. The set of merged structure-factor amplitudes was then subjected to phasing. Initial phases were calculated with REFMAC565 of CCP4 based on a structural model of SAMwt generated by homology modelling on the SWISS-MODEL web server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/)66,67 followed by molecular replacement with the program MOLREP68 in CCP4. The SAM domain of SAMSN1 (PDB ID: 1V38) was used for homology modelling. Model refinement was conducted with REFMAC5 and the program Phenix69. The molecular graphics software Coot70 was employed for visual inspection, building and manual improvement of the structural model. Crystallographic R-factors Rwork and Rfree were used to monitor the progress of the refinement process. The quality of the structure was validated with MolProbity71. Data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Supplementary Table S10.

Figures of structures were generated with UCSF Chimera72 using secondary structure assignments from the DSSP program39. The PISA webserver59 was used to analyse the multimeric state.

Translational diffusion measurements

One-dimensional 15N-edited diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY)73 was used to measure D of SAMlg. DOSY experiments were conducted at 30 °C on 15N-labelled SAMlg at 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM in NMR buffer. Extrapolation of the functional dependency of D on protein concentration to infinite dilution provides D0. Assuming a spherical shape of the diffusing particles, the simplified Stokes-Einstein relation was used to relate D0 to the hydrodynamic radius Rh:

The viscosity η of the solvent (90% H2O/10% 2H2O) was calculated as described previously74.

Accession codes

NMR resonance assignments of the SLy1 SAMC have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (accession code 27432). The NMR structures of the SLy1 SAMC homodimer have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6G8O). Atomic coordinates and structure factors for SLy1 SAMwt have been deposited in the PDB (ID: 6FXF). The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

L.K. was a scholarship holder of the Graduate School “Molecules of Infection (MOI)” funded by the Jürgen Manchot Foundation. P.T.-R. thanks Rudolf Hartmann and Melanie Schwarten for support in NMR data acquisition. Access to the Biomolecular NMR Centre, jointly run by Forschungszentrum Jülich and Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, is acknowledged. We are grateful to the beamline scientists at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF; Grenoble, France) for providing assistance with the use of beamline ID30A-3.

Author Contributions

L.K., A.J.D., K.P., S.B.H., D.W., and B.W.K. conceived and designed the study; L.K., P.T.-R. and K.H. performed cloning, expression and purification of protein; L.K., A.J.D., P.T.-R., D.C., V.P., and M.S. recorded and analysed NMR data; L.K., J.G. and R.B.-S. grew crystals, collected and analysed X-ray data and determined the crystal structure; L.N.-S. conducted and interpreted the AUC experiments; L.K. and P.T.-R. performed and analysed MST experiments; L.K., A.J.D. and B.W.K. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dieter Willbold, Email: d.willbold@fz-juelich.de.

Bernd W. Koenig, Email: b.koenig@fz-juelich.de

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-37185-3.

References

- 1.Beer S, Simins AB, Schuster A, Holzmann B. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel SH3 protein (SLY) preferentially expressed in lymphoid cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1520:89–93. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astoul E, et al. Approaches to define antigen receptor-induced serine kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9267–9275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beer S, et al. Impaired immune responses and prolonged allograft survival in Sly1 mutant mice. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:9646–9660. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9646-9660.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis B, Pfeffer K, Beer-Hammer S. The orphan adapter protein SLY1 as a novel anti-apoptotic protein required for thymocyte development. BMC Immunology. 2009;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schäll D, Schmitt F, Reis B, Brandt S, Beer-Hammer S. SLy1 regulates T-cell proliferation during Listeria monocytogenes infection in a Foxo1-dependent manner. European J. of Immunol. 2015;45:3087–3097. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arefanian S, et al. Deficiency of the adaptor protein SLy1 results in a natural killer cell ribosomopathy affecting tumor clearance. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1238543. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1238543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer BJ. SH3 domains: complexity in moderation. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1253–1263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponting CP. SAM: a novel motif in yeast sterile and Drosophila polyhomeotic proteins. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1928–1930. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiao, F. & Bowie, J. U. The many faces of SAM. Sci STKE, re7; 10.1126/stke.2862005re7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Harkiolaki M, Gilbert RJC, Jones EY, Feller SM. The C-terminal SH3 domain of CRKL as a dynamic dimerization module transiently exposing a nuclear export signal. Structure. 2006;14:1741–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinson, N. M., Visperas, P. R. & Kuriyan, J. The Tyrosine Kinase Csk Dimerizes through Its SH3 Domain. PloS one4, 10.1371/journal.pone.0007683 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Green JB, Gardner CD, Wharton RP, Aggarwal AK. RNA recognition via the SAM domain of Smaug. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1537–1548. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson PE, Donaldson LW. RNA recognition by the Vts1p SAM domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:177–178. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrera FN, Poveda JA, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Neira JL. Binding of the C-terminal sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain of human p73 to lipid membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46878–46885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, et al. Solution structures, dynamics, and lipid-binding of the sterile alpha-motif domain of the deleted in liver cancer 2. Proteins. 2007;67:1154–1166. doi: 10.1002/prot.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stapleton D, Balan I, Pawson T, Sicheri F. The crystal structure of an Eph receptor SAM domain reveals a mechanism for modular dimerization. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:44–49. doi: 10.1038/4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharjya S, et al. Solution structure of the dimeric SAM domain of MAPKKK Ste11 and its interactions with the adaptor protein Ste50 from the budding yeast: implications for Ste11 activation and signal transmission through the Ste50-Ste11 complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:1071–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimshaw SJ, et al. Structure of the sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-modulating protein STE50 and analysis of its interaction with the STE11 SAM. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2192–2201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thanos CD, Goodwill KE, Bowie JU. Oligomeric structure of the human EphB2 receptor SAM domain. Science. 1999;283:833–836. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CA, et al. Polymerization of the SAM domain of TEL in leukemogenesis and transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 2001;20:4173–4182. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meruelo AD, Bowie JU. Identifying polymer-forming SAM domains. Proteins. 2009;74:1–5. doi: 10.1002/prot.22232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiao F, et al. Derepression by depolymerization: Structural insights into the regulation of Yan by Mae. Cell. 2004;118:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajakulendran T, et al. CNK and HYP form a discrete dimer by their SAM domains to mediate RAF kinase signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2836–2841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709705105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramachander R, et al. Oligomerization-dependent association of the SAM domains from Schizosaccharomyces pombe Byr2 and Ste4. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39585–39593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercurio FA, et al. Heterotypic Sam-Sam Association between Odin-Sam1 and Arap3-Sam: Binding Affinity and Structural Insights. Chembiochem. 2013;14:100–106. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercurio FA, et al. Solution Structure of the First Sam Domain of Odin and Binding Studies with the EphA2 Receptor. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2136–2145. doi: 10.1021/bi300141h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leone M, Cellitti J, Pellecchia M. NMR Studies of a Heterotypic Sam-Sam Domain Association: The Interaction between the Lipid Phosphatase Ship2 and the EphA2 Receptor. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12721–12728. doi: 10.1021/bi801713f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald CB, Seldeen KL, Deegan BJ, Lewis MS, Farooq A. Grb2 adaptor undergoes conformational change upon dimerization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;475:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougherty MK, Morrison DK. Unlocking the code of 14-3-3. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1875–1884. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu HB, et al. SLP-76 Sterile alpha Motif (SAM) and Individual H5 alpha Helix Mediate Oligomer Formation for Microclusters and T-cell Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:29539–29549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bardiaux B, et al. Influence of different assignment conditions on the determination of symmetric homodimeric structures with ARIA. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2009;75:569–585. doi: 10.1002/prot.22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junius FK, ODonoghue SI, Nilges M, Weiss AS, King GF. High resolution NMR solution structure of the leucine zipper domain of the c-Jun homodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13663–13667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilges M. A calculation strategy for the structure determination of symmetric dimers by 1H NMR. Proteins. 1993;17:297–309. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS plus: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Habeck M, Rieping W, Linge JP, Nilges M. NOE assignment with ARIA 2.0: the nuts and bolts. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;278:379–402. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rieping W, et al. ARIA2: automated NOE assignment and data integration in NMR structure calculation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:381–382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang YJ, Rosato A, Singh G, Montelione GT. RPF: a quality assessment tool for protein NMR structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W542–W546. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim CA, Bowie JU. SAM domains: uniform structure, diversity of function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:625–628. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Touw WG, et al. A series of PDB-related databanks for everyday needs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D364–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt B, Ho L, Hogg PJ. Allosteric disulfide bonds. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7429–7433. doi: 10.1021/bi0603064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleywegt GJ. Use of non-crystallographic symmetry in protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr D. 1996;52:842–857. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995016477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkins DK, et al. Hydrodynamic radii of native and denatured proteins measured by pulse field gradient NMR techniques. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16424–16431. doi: 10.1021/bi991765q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metcalf DG, et al. NMR analysis of the alpha IIb beta 3 cytoplasmic interaction suggests a mechanism for integrin regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22481–22486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huttlin EL, et al. A Tissue-Specific Atlas of Mouse Protein Phosphorylation and Expression. Cell. 2010;143:1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodcock JM, Murphy J, Stomski FC, Berndt MC, Lopez AF. The dimeric versus monomeric status of 14-3-3 zeta is controlled by phosphorylation of Ser(58) at the dimer interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36323–36327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graille M, et al. Activation of the LicT transcriptional antiterminator involves a domain swing/lock mechanism provoking massive structural changes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:14780–14789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baaske P, Wienken CJ, Reineck P, Duhr S, Braun D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010. Optical Thermophoresis for Quantifying the Buffer Dependence of Aptamer Binding; pp. 2238–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wishart DS, et al. H-1, C-13 and N-15 Chemical-Shift Referencing in Biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vranken WF, et al. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwahlen C, et al. Methods for measurement of internuclear NOEs by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy: Application to a bacteriophage l N-peptide/boxB RNA complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6711–6721. doi: 10.1021/ja970224q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez C, Lohr F, Ruterjans H, Schmidt JM. Self-consistent Karplus parametrization of (3)J couplings depending on the polypeptide side-chain torsion chi(1) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7081–7093. doi: 10.1021/ja003724j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cordier F, Grzesiek S. Direct observation of hydrogen bonds in proteins by interresidue (3h)J(NC ‘) scalar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1601–1602. doi: 10.1021/ja983945d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nilges M, et al. Accurate NMR structures through minimization of an extended hybrid energy. Structure. 2008;16:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Cryst. D. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evans PR. An introduction to data reduction: space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Cryst. D. 2011;67:282–292. doi: 10.1107/S090744491003982X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Cryst. D. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matthews BW. Solvent Content of Protein Crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst. D. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Biasini M, et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adams PD, et al. Acta Cryst. D. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution; pp. 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst. D. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Johnson CS. Diffusion ordered nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: principles and applications. Prog. Nucl. Mag. Res. Sp. 1999;34:203–256. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6565(99)00003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cho CH, Urquidi J, Singh S, Robinson GW. Thermal offset viscosities of liquid H2O, D2O, and T2O. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:1991–1994. doi: 10.1021/jp9842953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nanyes DR, et al. Multiple polymer architectures of human polyhomeotic homolog 3 sterile alpha motif. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2014;82:2823–2830. doi: 10.1002/prot.24645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.