Abstract

Recurrent acute bacterial cholangitis is a unique indication for liver transplantation in primary sclerosing cholangitis. We present the first report on utility of healthy donor fecal transplantation for management of recurrent acute bacterial cholangitis in a primary sclerosing cholangitis patient. We demonstrate the striking liver biochemistry, bile acid and bacterial community changes following intestinal microbiota transplantation associated with amelioration of recurrent cholangitis.

Keywords: FMT, Sclerosing cholangitis, Stool transplant, Gut microbiome, Microbiota

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare disease with multiple etiopathogenetic mechanisms that lead to chronic biliary inflammation and fibrosis of the intra- and/or extra-hepatic biliary tree, leading to cirrhosis and sometimes associated with malignancies of the biliary tree. Current available standard medical therapies do not benefit the overall survival, and liver transplantation (LT) remains the only curative therapy.1,2 The gut microbiota has been implicated as a central factor in the pathophysiology of PSC. Tabibian and colleagues3 demonstrated the importance of commensal microbiota and its metabolites in protecting against biliary injury and suggested future directives such as microbiota-based biomarkers and therapeutic interventions in PSC.

The fact that microbiota plays an important role in the pathogenesis and as well progression of PSC has been demonstrated through multiple trials that utilized antibiotics, such as metronidazole and vancomycin, that have effectively shown to improve liver biochemistry.4 Sabino et al.5 investigated the gut microbial composition in patients with PSC and demonstrated that PSC had a characteristic microbial signature that is independent from inflammatory bowel disease. These data suggest that manipulation of the gut microbiota could potentially influence the disease process in PSC.

Recurrent acute bacterial cholangitis (BC) in the presence or absence of dominant strictures and not responding to intensive medical management is a unique indication for LT in patients with PSC.2 We present herein novel clinical and metagenomic data for a patient with recurrent acute BC associated with PSC, who was listed for LT and in whom BC episodes were ameliorated for a year after healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

Case report

A 38-year-old non-smoker and teetotaler male diagnosed with PSC without inflammatory bowel disease (the latter ruled out by colonoscopy-directed mucosal biopsy at 3 months prior to current presentation), for 3 years and on ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) at 15 mg/kg/day had developed three episodes of BC within the prior 6 months, with the last episode requiring intensive care unit admission for septic shock. Magnetic resonance cholangiography revealed mucosal irregularities in the right and left hepatic duct with areas of beading in segments 3, 6 and 8 of the liver in the absence of dominant strictures. Test of immunoglobulin type G4 serum level was normal, and its associated systemic manifestations were absent. Level of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 was within normal limits in the absence of cholangitis, and parenchymal or bile duct lesions suggestive of cholangiocarcinoma were not evident on serial follow-up imaging.

In view of the recurrent BC, the patient was listed for LT. While on the wait list, the patient developed persistent pruritus (Itch score 6/10) and jaundice lasting for 3 months and experienced a fourth episode of BC. Two out of three prior episodes of BC were associated with Escherichia coli bacteremia sensitive to cephalosporins and carbapenems, respectively. The recent episode of BC was associated with Enterococcus fecalis sensitive to linezolid, to which the patient responded clinically. Considering the high mortality associated with being on an LT wait list, manipulation of the intestinal microbiota through healthy donor FMT (to potentially influence the disease process in PSC)2 was considered, with informed consent from the patient and his wife. The patient’s nephew was identified as the potential donor, after standard screening protocol.6

Sixty grams of freshly collected stool sample was obtained 6 hours before the procedure and homogenized in a blender with 250 mL of normal saline for 2–4 minutes. Two hundred milliliters of the strained and filtered stool were delivered through an endoscope to the second part of the patient’s duodenum. Endoscopic FMT was performed once weekly for 4 weeks. All antibiotics were withheld during this period, but the UDCA was continued.

Blood biochemistries, total and fractionated serum bile acids and stool microbial community analyses were performed at baseline and before each scheduled FMT and at the end of 1 year following the treatment. Microbiome analysis was conducted on colonic stool samples as per standard protocol. Briefly, sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq next-generation sequencer (Illumina, CA, USA) and classified taxonomically according to the GreenGenes Database (version 13.8). The Shannon diversity index was used to describe species diversity in each bacterial community, while Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME), Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway were used to ascertain quantitative and qualitative microbial communities and their respective functional pathways.7

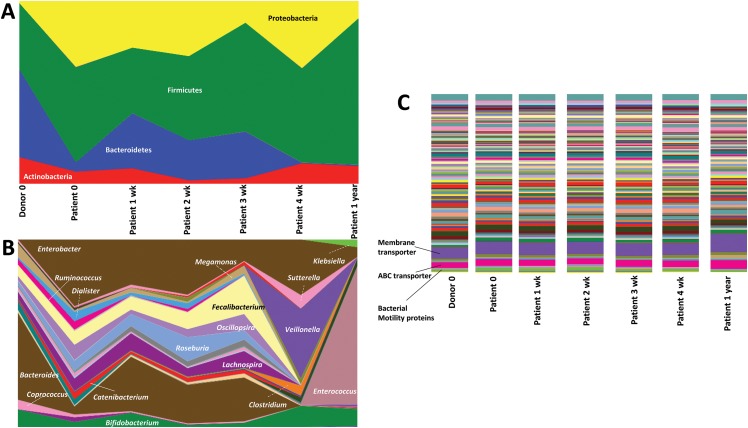

The patient was afebrile and anicteric after the third and fourth sessions of FMT, respectively, and remained so up to 1 year. Pruritus worsened up to 6 weeks after the FMT (maximal score of 8/10), steadily decreasing to tolerable levels (2/10) thereafter. Notable improvements in liver functions (Table 1) and circulating total and toxic bile acids (Table 2) associated with distinctive modification of bacterial communities and their functions, from the baseline were noted. Relative abundance of Proteobacteria was higher in the patient at baseline, while Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria were higher in the healthy donor. Bifidobacterium, Coprococcus Megamonas and Bacteroides were higher in the donor at baseline while Enterobacter, Catenibacterium and Dialister were noted to be higher in the patient at baseline. During the period of FMT, striking changes were seen with reduction in relative abundance of Proteobacteria and concomitant increase in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. At the genus level, bacteria that were predominant in the donor increased during FMT in the patient (Bacteroides, Megamonas, Bifidobacterium) with emergence of species that were absent at baseline (Clostridium, Veillonella). Some species that were present at baseline in the patient, were completely absent at the end of the 4 weeks of FMT (Fecalibacterium, Oscillopsira, Lachnospira).

Table 1. Liver function tests at baseline, during and after completion of fecal microbiota transplantation in our patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis and recurrent bacterial cholangitis.

| Time | Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | Gamma glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | Serum albumin (g/dL) | International normalized ratio |

| Baseline | 6.8 | 4.2 | 88 | 128 | 456 | 332 | 3.2 | 1.46 |

| End of 1st week of FMT | 7.2 | 4.8 | 92 | 132 | 502 | 288 | 3.1 | 1.42 |

| End of 2nd week of FMT | 6.8 | 3.1 | 90 | 112 | 662 | 292 | 3.1 | 1.51 |

| End of 3rd week of FMT | 4.3 | 3.2 | 97 | 118 | 886 | 342 | 2.9 | 1.61 |

| End of 4th week of FMT | 3.6 | 2.2 | 94 | 132 | 792 | 316 | 3.2 | 1.48 |

| 3 months post FMT | 2.8 | 1.6 | 78 | 98 | 344 | 189 | 3.4 | 1.32 |

| 6 months post FMT | 1.8 | 0.9 | 72 | 68 | 286 | 184 | 3.4 | 1.34 |

| 9 months post FMT | 2.0 | 0.8 | 66 | 56 | 214 | 164 | 3.2 | 1.28 |

| 12 months post FMT | 9.4 | 4.9 | 79 | 97 | 352 | 246 | 3.1 | 1.64 |

Table 2. Total and fractioned bile acids at baseline, during and after completion of fecal microbiota transplantation in our patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis and recurrent bacterial cholangitis.

| Time | Total bile acids (μmol/L) | Cholic acid (μmol/L) | Deoxycholic acid (μmol/L) | Chenodeoxycholic acid (μmol/L) |

| Baseline | 86.4 | 33.6 | <0.5 | 52.8 |

| End of 1st week of FMT | 73 | 18.7 | 2.6 | 51.7 |

| End of 2nd week of FMT | 55.9 | 15.5 | <0.5 | 40.4 |

| End of 3rd week of FMT | 64.5 | 17.9 | <0.5 | 46.6 |

| End of 4th week of FMT | 52.6 | 18.4 | <0.5 | 32.8 |

| 6 months post FMT | 48.7 | 21.9 | 1.3 | 24.4 |

| 12 months post FMT | 68 | 18.8 | <0.5 | 48.7 |

| Reference ranges | ≤6.8 | ≤1.8 | 2.4 | 3.1 |

Pathways associated with membrane transport, especially ATP-binding cassette transport and proteins associated with bacterial motility, were modified after FMT (Fig. 1). One year after FMT, cholangitis recurred (managed with broad spectrum antibiotics in the absence of blood culture positivity) with marked pathogenic changes in gut microbial communities and emergence of pathogenic species that were not evident at baseline in either the patient or the donor. The patient was offered a second cycle of FMT but declined and was referred to an LT center for work-up and relisting on the LT wait list.

Fig. 1. (A) Area plot of predominant bacterial phyla on 16s metagenomic analysis of stool samples of the patient at baseline, during and one year after healthy donor fecal transplantation.

(B) Area plot of predominant bacterial genera on 16s metagenomic analysis of stool samples of the patient at baseline, during and one year after healthy donor fecal transplantation. (C) Histogram representation of multiple metabolic pathways that were upregulated and downregulated from the baseline, during and after healthy donor fecal transplantation at one year.

Discussion

Healthy donor FMT for PSC has been shown recently to improve microbiome diversity and liver biochemistries in PSC.8 Bajer and co-workers9 showed that Rothia, Enterococcus, Streptococcus and Veillonella were markedly overrepresented, while Coprococcus, Adlercreutzia and Prevotella were reduced in patients with PSC, regardless of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease; this was more or less similar to our findings at baseline. Pereira et al.10 suggested that the etiology of PSC was not associated with changes in bile microbial communities and that Streptococcus played a potential pathogenic role in the progression of the disease.

One-year transplant-free survival (TFS) and amelioration of recurrent acute BC through FMT in PSC has not been demonstrated. Multiple studies have shown that in patients with PSC, improvements in serum alkaline phosphatase (spontaneously or more often with UDCA therapy) lead to better prognosis. However, larger placebo-controlled studies on UDCA treatment did not demonstrate any effect on symptoms or time to transplantation. Findings from the largest multicenter study of PSC with 15-year follow-up supported no role for UDCA in improving clinical events or TFS. In a recent analysis, an increased serum concentration of lithocholic acid, a potent hydrophobic bile acid, in PSC patients given high-dose UDCA was found to be associated with adverse outcomes and, hence, UDCA dosing >28 mg/kg was curtailed.10

Antibiotic therapy appears promising in PSC, particularly in the face of mounting evidence for the recognized role of the intestinal microbiome in pathogenesis of PSC. But, the issue of evolving resistance and prevention of disease progression remains a real concern for clinicians.11 In the patient, cyclic antibiotics along with UDCA failed to improve acute BC episodes or liver biochemistries, but the use of FMT improved clinical as well as liver biochemistry.

In our patient, at the phylum level we see a decrease of Proteobacteria (a phylum containing numerous human pathogens) and an increase of Firmicutes abundance (a phylum with many taxa, having presumed beneficial immunologic properties). This would clearly favor FMT in PSC. However, on the genus level we see an increase of Klebsiella and Enterococcus, which likely have proinflammatory enteric effects and constitute an important enteric source of pathogens in BC in PSC. Furthermore, Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, both butyric acid producing taxa with well-established beneficial immunoregulatory effects, are reported to decrease in the patient over time. But, this has been demonstrated only in patients with ulcerative colitis and not in those with PSC.12 Nevertheless, even in the presence of pathogenic bacterial evolution in the subsequent months after FMT, beneficial metabolic functional pathways are still active. Hence, the mere presence of pathogenic species may not truly reflect clinical outcomes, but they may affect microbiome functionality, which is more important.

The reason behind the spontaneous pathogenic changes in our patient cannot be clearly explained at this time. The effect might be secondary to a failure of coinhabitation of beneficial species in the long term due to other active ‘drivers’ of disease pathogenesis.13 This would clearly question the beneficial effect of FMT in PSC, or at least advocate that FMT may be a useful short term means to extend TFS but not be appropriate as a long-term solution; it may even may be adverse in the intermediate to long term. An important finding that supports the improvement in TFS may be the striking beneficial modulations seen in the circulating bile acids and the initial reduction in alkaline phosphatase. Spontaneous recovery from episodes of acute BC in the long term, even though likely, has not been well demonstrated in the natural history of the disease, and recurrence of BC is well known to have life threatening outcomes in patients of PSC.

In our patient, recurrent BC and its amelioration during a whole year after the FMT with clinical, biochemical and metagenomic evidence of improvement and modulation posttreatment is conceptual proof that the symptom-free period and TFS did not merely arise by chance, even though larger studies of this matter are required to confirm our findings. The recurrence of acute BC in the patient after 1 year of FMT seems to suggest that microbiota may be one of the ‘drivers’ of disease progression and manifestation; however, other factors may be associated with initiation and maintenance of dysbiosis in PSC or benefits of FMT may be finite with short-term use. These issues require further research, using studies that integrate multiomics, considering host and environmental factors, to fully understand the PSC spectrum.

Conclusions

We believe that patients with PSC with recurrent acute BC in the absence of advanced cirrhosis and decompensation could benefit from FMT through extension of TFS. This may decrease the transplant wait list burden, so that proper allocation of organs to those with higher liver disease severity scores could be realized. Larger studies are an unmet need.

Abbreviations

- BC

bacterial cholangitis

- FMT

fecal microbiota transplantation

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LT

liver transplantation

- PICRUSt

Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- QIIME

Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology

- TFS

liver transplant-free survival

- UDCA

ursodeoxycholic acid

References

- 1.Silveira MG, Lindor KD. Clinical features and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3338–3349. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1161–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1506330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabibian JH, O’Hara SP, Trussoni CE, Tietz PS, Splinter PL, Mounajjed T, et al. Absence of the intestinal microbiota exacerbates hepatobiliary disease in a murine model of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2016;63:185–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.27927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabibian JH, Weeding E, Jorgensen RA, Petz JL, Keach JC, Talwalkar JA, et al. Randomised clinical trial: vancomycin or metronidazole in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis - a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:604–612. doi: 10.1111/apt.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabino J, Vieira-Silva S, Machiels K, Joossens M, Falony G, Ballet V, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is characterised by intestinal dysbiosis independent from IBD. Gut. 2016;65:1681–1689. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodworth MH, Neish EM, Miller NS, Dhere T, Burd EM, Carpentieri C, et al. Laboratory testing of donors and stool samples for fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1002–1010. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02327-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jovel J, Patterson J, Wang W, Hotte N, O’Keefe S, Mitchel T, et al. Characterization of the gut microbiome using 16S or shotgun metagenomics. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:459. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allegretti JR, Kassam Z, Carrellas M, Timberlake S, Gerardin Y, Pratt D, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves microbiome diversity and liver enzyme profile in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Program No. P1425. World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG2017 Meeting Abstracts; Orlando, FL: American College of Gastroenterology; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajer L, Kverka M, Kostovcik M, Macinga P, Dvorak J, Stehlikova Z, et al. Distinct gut microbiota profiles in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4548–4558. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i25.4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira P, Aho V, Arola J, Boyd S, Jokelainen K, Paulin L, et al. Bile microbiota in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Impact on disease progression and development of biliary dysplasia. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goode EC, Rushbrook SM. A review of the medical treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis in the 21st century. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7:68–85. doi: 10.1177/2040622315605821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabibian JH, Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Role of the microbiota and antibiotics in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:389537. doi: 10.1155/2013/389537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, De Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63:1275–1283. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]