Abstract

Background: Recently, the roles of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) polymorphisms in colorectal cancer (CRC) were analyzed by some pilot studies, with inconsistent results. Therefore, we performed the present study to better assess the relationship between TNF-α polymorphisms and the risk of CRC.

Methods: Eligible studies were searched in PubMed, Medline, Embase and CNKI. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess correlations between TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC.

Results: A total of 22 studies were included for analyses. A significant association with the risk of CRC was detected for TNF-α -308 G/A (recessive model: P = 0.004, OR = 1.42, 95%CI 1.12–1.79) polymorphism in overall analyses. Further subgroup analyses based on ethnicity of participants revealed that TNF-α -238 G/A was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Caucasians (dominant model: P = 0.01, OR = 0.47, 95%CI 0.26–0.86; overdominant model: P = 0.01, OR = 2.27, 95%CI 1.20–4.30; allele model: P = 0.02, OR = 0.51, 95%CI 0.29–0.90), while -308 G/A polymorphism was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Asians (recessive model: P = 0.001, OR = 2.23, 95%CI 1.38–3.63).

Conclusions: Our findings indicated that TNF-α -238 G/A polymorphism may serve as a potential biological marker for CRC in Caucasians, and TNF-α -308 G/A polymorphism may serve as a potential biological marker for CRC in Asians.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer (CRC), Gene polymorphisms, Meta-analysis, Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) refers to malignancy that occurs in the colon and rectum. It is the third most commonly seen cancer in men, and the second commonly seen cancer in women [1]. Despite rapid advances in early diagnosis and surgical treatment over the past few decades, CRC still accounts for approximately one-tenth of cancer-related deaths, making it one of the major threats to public health worldwide [2]. To date, the exact cause of CRC remains unclear. Although smoking, excessive alcohol intake and high consumption of red meat were already identified as potential risk factors of CRC [3–5]. The fact that a significant portion of CRC patients did not expose to any of these carcinogenic factors suggests that genetic susceptibility may play a crucial part in the pathogenesis of CRC [6].

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) plays a central role in the regulation of anti-tumor immune responses. Previous clinical investigations showed that serum TNF-α levels in CRC patients were significantly elevated [7], and patients with lower TNF-α levels had better prognosis compared with these with higher TNF-α levels [8,9]. Consequently, functional TNF-α polymorphisms were thought to be ideal candidate genetic markers of CRC. Recently, some pilot studies were conducted to investigate associations between TNF-α polymorphisms and the risk of CRC. But the results of these studies were conflicting [10–31]. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to better analyze the roles of TNF-α polymorphisms in the development of CRC.

Materials and methods

Literature search and inclusion criteria

This meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline [32]. Potentially eligible articles were searched in PubMed, Medline, Embase and CNKI using the combination of following key words: ‘tumor necrosis factor-α’, ‘TNF-α’, ‘polymorphism’, ‘variant’, ‘mutation’, ‘genotype’, ‘allele’, ‘colorectal’, ‘colon’, ‘rectal’, ‘cancer’, ‘tumor’, ‘carcinoma’, ‘neoplasm’ and ‘malignancy’. The initial literature search was conducted in 2018 February and the latest update was performed in 2018 July. The reference lists of all retrieved publications were also screened to identify other potentially relevant articles.

Included studies should meet all the following criteria: (1) case–control study on correlations between TNF-α polymorphisms and the risk of CRC; (2) provide adequate data to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs); (3) full text available. Studies were excluded if one of the following criteria was fulfilled: (1) not relevant to TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC; (2) family-based association studies; (3) case reports or case series; (4) abstracts, reviews, comments, letters and conference presentations. For duplicate reports, only the study with the largest sample size was included. No language restrictions were imposed in this meta-analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were extracted from included studies: (1) name of the first author; (2) year of publication; (3) country and ethnicity of participants; (4) the number of cases and controls and (5) genotypic distributions of TNF-α polymorphisms in cases and controls. Additionally, the probability value (P value) of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) test was also calculated based on genotypic frequency of TNF-α polymorphisms in the control group.

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was employed to assess the quality of eligible studies from three aspects: (1) selection of cases and controls; (2) comparability between cases and controls and (3) exposure in cases and controls [33]. The NOS has a score range of zero to nine, and studies with a score of more than seven were thought to be of high quality.

Two reviewers (Huang and Qin) conducted data extraction and quality assessment independently. When necessary, the reviewers wrote to the corresponding authors for extra information or raw data. Any disagreement between two reviewers was solved by discussion with the third reviewer (Jiang) until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses in the present study were conducted with Review Manager Version 5.3.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, United Kingdom). ORs and 95% CIs were used to assess potential associations of TNF-α polymorphisms with the risk of CRC in the dominant, recessive, overdominant and allele models, and a P value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated based on Q test and I2 statistic. If P value of Q test was less than 0.1 or I2 was greater than 50%, random-effect models (REMs) would be used for analyses due to the existence of significant heterogeneities. Otherwise, fixed-effect models (FEMs) would be applied for analyses. Subgroup analyses by ethnicity of participants were subsequently conducted to obtain more specific results. Sensitivity analyses were carried out to test the stability of the results. Funnel plots were applied to evaluate possible publication bias.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

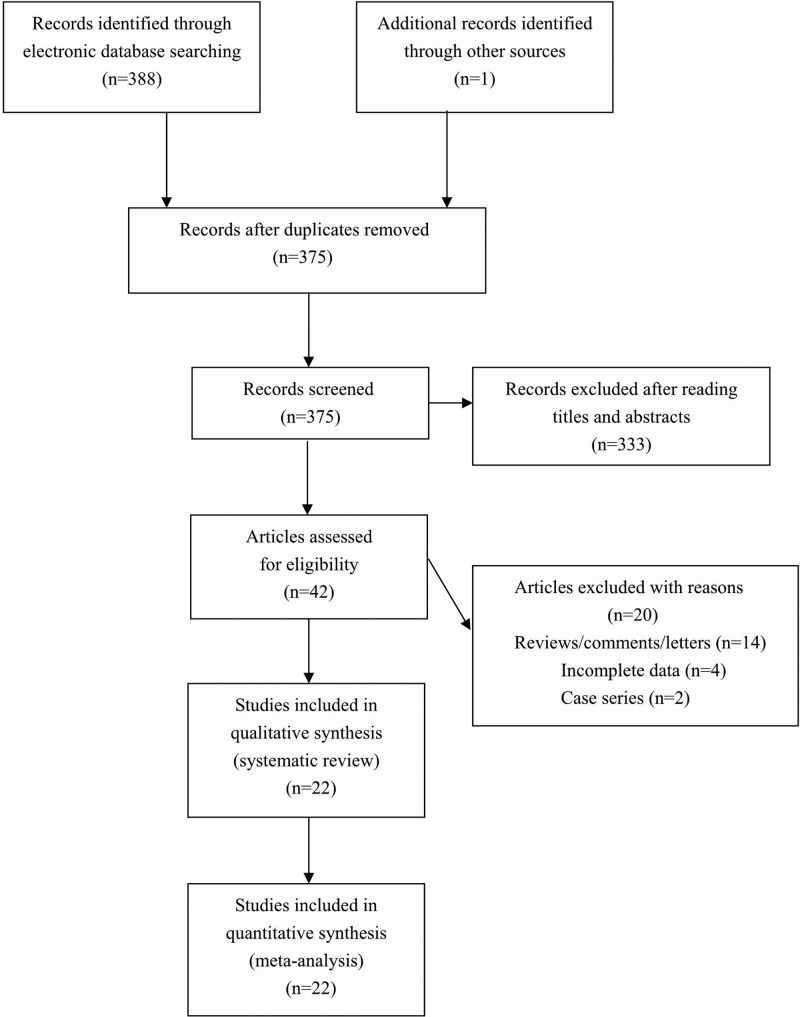

The literature search identified 389 potentially relevant articles. After exclusion of irrelevant and duplicate articles by reading titles and abstracts, 42 articles were retrieved for further evaluation. Another 20 articles were subsequently excluded after reading the full text. Finally, a total of 22 eligible studies were included in this meta-analysis (see Figure 1). Characteristics of included studies were summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection for the present study.

Table 1. The characteristics of included studies for TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC.

| First author, year | Country | Ethnicity | Source of controls | Sample size | Genotype distribution | P-value for HWE | NOS score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||||||

| -238 G/A | GG/GA/AA | |||||||

| Garrity-Park 2008 [13] | USA | Mixed | HB | 114/114 | 109/5/0 | 107/6/1 | 0.017 | 8 |

| Gutiérrez-Hurtado 2016 [15] | Mexico | Mixed | PB | 143/49 | 127/14/2 | 42/6/1 | 0.199 | 7 |

| Hamadien 2016 [16] | Saudi Arabia | Caucasian | PB | 100/100 | 86/13/1 | 97/2/1 | <0.001 | 8 |

| Jang 2001 [17] | Korea | Asian | PB | 27/92 | 27/0/0 | 80/11/1 | 0.391 | 8 |

| Kapitanović 2014 [18] | Croatia | Caucasian | PB | 200/200 | 181/18/1 | 188/11/1 | 0.076 | 8 |

| Madani 2008 [24] | Iran | Caucasian | PB | 51/46 | 51/0/0 | 45/1/0 | 0.941 | 7 |

| Wang 2008 [31] | China | Asian | PB | 343/670 | 320/22/1 | 620/50/0 | 0.316 | 8 |

| -308 G/A | GG/GA/AA | |||||||

| Banday 2016 [10] | India | Caucasian | PB | 142/184 | 124/18/0 | 150/34/0 | 0.167 | 8 |

| Basavaraju 2015 [11] | UK | Caucasian | PB | 388/495 | 253/117/18 | 309/167/19 | 0.543 | 7 |

| Burada 2013 [12] | Romania | Caucasian | PB | 144/233 | 115/26/3 | 189/42/2 | 0.842 | 8 |

| Garrity-Park 2008 [13] | USA | Mixed | HB | 114/114 | 52/49/13 | 92/20/2 | 0.464 | 8 |

| Gunter 2006 [14] | USA | Mixed | PB | 217/202 | 146/59/12 | 139/57/6 | 0.957 | 8 |

| Gutiérrez-Hurtado 2016 [15] | Mexico | Mixed | PB | 164/209 | 139/21/4 | 180/27/2 | 0.392 | 7 |

| Hamadien 2016 [16] | Saudi Arabia | Caucasian | PB | 100/100 | 67/23/10 | 59/23/18 | <0.001 | 8 |

| Jang 2001 [17] | Korea | Asian | PB | 27/92 | 24/3/0 | 85/7/0 | 0.704 | 8 |

| Kapitanović 2014 [18] | Croatia | Caucasian | PB | 200/200 | 163/35/2 | 163/35/2 | 0.937 | 8 |

| Landi 2003 [19] | France | Caucasian | PB | 363/320 | 278/80/5 | 234/76/10 | 0.220 | 7 |

| Li 2011 [21] | China | Asian | PB | 180/180 | 156/15/9 | 160/19/1 | 0.599 | 8 |

| Li 2017 [22] | China | Asian | PB | 569/570 | 500/66/3 | 493/75/2 | 0.632 | 8 |

| Macarthur 2005 [23] | UK | Caucasian | PB | 246/389 | 157/74/15 | 224/145/20 | 0.577 | 8 |

| Park 1998 [25] | Korea | Asian | PB | 136/331 | 40/71/25 | 148/151/32 | 0.465 | 7 |

| Stanilov 2014 [26] | Bulgaria | Caucasian | PB | 119/177 | 88/28/3 | 135/40/2 | 0.612 | 8 |

| Suchy 2008 [27] | Poland | Caucasian | PB | 350/350 | 254/87/9 | 248/95/7 | 0.546 | 8 |

| Theodoropoulos 2006 [28] | Greece | Caucasian | PB | 222/200 | 152/56/14 | 146/44/10 | 0.010 | 7 |

| Toth 2007 [29] | Hungary | Caucasian | PB | 183/141 | 132/48/3 | 111/30/0 | 0.157 | 7 |

| Tsilidis 2009 [30] | USA | Mixed | PB | 204/372 | 146/55/3 | 275/90/7 | 0.908 | 7 |

| Wang 2008 [31] | China | Asian | PB | 344/669 | 284/58/2 | 554/111/4 | 0.538 | 8 |

| -857 C/T | CC/CT/TT | |||||||

| Garrity-Park 2008 [13] | USA | Mixed | HB | 114/114 | 98/16/0 | 92/22/0 | 0.254 | 8 |

| Hamadien 2016 [16] | Saudi Arabia | Caucasian | PB | 100/100 | 85/15/0 | 85/15/0 | 0.417 | 8 |

| Kapitanović 2014 [18] | Croatia | Caucasian | PB | 200/200 | 130/64/6 | 126/67/7 | 0.599 | 8 |

| Landi 2006 [20] | Spain | Caucasian | PB | 281/268 | 219/58/4 | 220/45/3 | 0.684 | 7 |

| Suchy 2008 [27] | Poland | Caucasian | PB | 350/350 | 253/88/9 | 242/98/10 | 0.983 | 8 |

| -863 C/A | CC/CA/AA | |||||||

| Garrity-Park 2008 [13] | USA | Mixed | HB | 114/114 | 84/28/2 | 80/33/1 | 0.224 | 8 |

| Suchy 2008 [27] | Poland | Caucasian | PB | 350/350 | 262/77/11 | 257/83/10 | 0.302 | 8 |

| -1031 T/C | TT/TC/CC | |||||||

| Garrity-Park 2008 [13] | USA | Mixed | HB | 114/114 | 79/31/4 | 75/36/3 | 0.588 | 8 |

| Kapitanović 2014 [18] | Croatia | Caucasian | PB | 200/200 | 132/56/12 | 135/54/11 | 0.082 | 8 |

| Suchy 2008 [27] | Poland | Caucasian | PB | 350/350 | 250/90/10 | 227/107/16 | 0.460 | 8 |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; NA, not available; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Overall and subgroup analyses

To investigate potential correlations of TNF-α polymorphisms with the risk of CRC, 7 studies about TNF-α -238 G/A polymorphism (901 cases and 1179 controls), 20 studies about TNF-α -308 G/A polymorphism (4412 cases and 5528 controls), 5 studies about TNF-α -857 C/T polymorphism (1045 cases and 1032 controls), 2 studies about TNF-α -863 C/A polymorphism (464 cases and 464 controls) and 3 studies about TNF-α -1031 T/C polymorphism (664 cases and 664 controls) were enrolled for analyses. A significant association with the risk of CRC was detected for TNF-α -308 G/A (recessive model: P = 0.004, OR = 1.42, 95%CI 1.12–1.79) polymorphism in overall analyses.

Further subgroup analyses based on ethnicity of participants revealed that TNF-α -238 G/A was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Caucasians (dominant model: P = 0.01, OR = 0.47, 95%CI 0.26–0.86; overdominant model: P = 0.01, OR = 2.27, 95%CI 1.20–4.30; allele model: P = 0.02, OR = 0.51, 95%CI 0.29–0.90), while -308 G/A polymorphism was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Asians (recessive model: P = 0.001, OR = 2.23, 95%CI 1.38–3.63). No any other positive results were found for investigated polymorphisms in overall and subgroup analyses (see Table 2).

Table 2. Overall and subgroup analyses for TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC.

| Polymorphisms | Population | Sample size | Dominant comparison | Recessive comparison | Overdominant comparison | Allele comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | |||

| -238 G/A | Overall | 901/1179 | 0.72 | 0.94 (0.68–1.31) | 0.94 | 1.04 (0.34–3.20) | 0.68 | 1.07 (0.77-1.51) | 0.77 | 0.95 (0.70–1.31) |

| Caucasian | 351/346 | 0.01 | 0.47 (0.26–0.86) | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.14–7.15) | 0.01 | 2.27 (1.20-4.30) | 0.02 | 0.51 (0.29–0.90) | |

| Asian | 370/762 | 0.31 | 1.29 (0.79–2.12) | 0.34 | 2.69 (0.35–20.78) | 0.26 | 0.75 (0.45–1.24) | 0.38 | 1.24 (0.77–2.00) | |

| -308 G/A | Overall | 4412/5528 | 0.30 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.004 | 1.42 (1.12–1.79) | 0.84 | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.17 | 0.90 (0.77–1.05) |

| Caucasian | 2457/2789 | 0.21 | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) | 0.76 | 1.05 (0.77–1.42) | 0.15 | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | 0.32 | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) | |

| Asian | 4412/5528 | 0.27 | 0.83 (0.60–1.15) | 0.001 | 2.23 (1.38–3.63) | 0.90 | 1.01 (0.83–1.24) | 0.16 | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | |

| -857 C/T | Overall | 1045/1032 | 0.62 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 0.85 | 0.94 (0.50–1.78) | 0.66 | 0.95 (0.78–1.17) | 0.62 | 1.05 (0.87–1.25) |

| Caucasian | 931/918 | 0.85 | 1.02 (0.83–1.26) | 0.85 | 0.94 (0.50–1.78) | 0.89 | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) | 0.82 | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | |

| -863 C/A | Overall | 464/464 | 0.50 | 1.11 (0.83–1.48) | 0.68 | 1.19 (0.53–2.68) | 0.40 | 0.88 (0.65–1.19) | 0.64 | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) |

| -1031 T/C | Overall | 664/664 | 0.16 | 1.18 (0.94–1.48) | 0.58 | 0.86 (0.50–1.47) | 0.22 | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) | 0.16 | 1.15 (0.95–1.40) |

| Caucasian | 550/550 | 0.20 | 1.18 (0.92–1.52) | 0.47 | 0.81 (0.45–1.44) | 0.31 | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) | 0.17 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; NA, not available; OR, odds ratio; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

For -238 G/A, Dominant comparison: G/A + A/A vs. G/G; Recessive comparison: A/A vs. G/G + G/A; Overdominant comparison: G/G + A/A vs. G/A; Allele comparison: G vs. A.

For -308 G/A, Dominant comparison: G/A + A/A vs. G/G; Recessive comparison: A/A vs. G/G + G/A; Overdominant comparison: G/G + A/A vs. G/A; Allele comparison: G vs. A.

For -857 C/T, Dominant comparison: C/T + T/T vs. C/C; Recessive comparison: T/T vs. C/C + C/T; Overdominant comparison: C/C + T/T vs. C/T; Allele comparison: C vs. T.

For -863 C/A, Dominant comparison: C/A + A/A vs. C/C; Recessive comparison: A/A vs. C/C + C/A; Overdominant comparison: C/C + A/A vs. C/A; Allele comparison: C vs. A.

For -1031 T/C, Dominant comparison: T/C + C/C vs. T/T; Recessive comparison: C/C vs. T/T + T/C; Overdominant comparison: T/T + C/C vs. T/C; Allele comparison: T vs. C.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were carried out to examine the stability of meta-analysis results by eliminating studies that deviated from HWE. No changes of results were observed in any comparisons, which indicated that our findings were statistically reliable.

Publication biases

Potential publication biases in the current study were evaluated with funnel plots. No obvious asymmetry of funnel plots was observed in any comparisons, which suggested that our findings were unlikely to be influenced by severe publication biases.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is so far the most comprehensive meta-analysis on correlations between TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC. A significant association with the risk of CRC was detected for TNF-α -308 G/A polymorphism in overall analyses. Further subgroup analyses based on ethnicity of participants revealed that TNF-α -238 G/A was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Caucasians, while -308 G/A polymorphism was significantly correlated with the risk of CRC in Asians. No any other positive results were found for investigated polymorphisms in overall and subgroup analyses. The stability of the synthetic results was subsequently evaluated in sensitivity analyses, and no changes of results were observed in any comparisons, which indicated that our findings were quite stable and reliable.

It is worth noting that -238 G/A and -308 G/A polymorphisms were two functional polymorphisms located in the promoter region of TNF-α, and the mutant alleles of these two polymorphisms were both associated with a higher expression level of TNF-α [10–15]. Thus, it is rational to speculate that subjects carrying mutant alleles of these two polymorphisms may have a relatively lower risk of CRC. From our results, you can see that the trends of developing CRC for these two polymorphisms in overall population are quite similar. But opposite findings were detected in further subgroup analyses. These contradictory findings in subgroup analyses may partially attribute to quite different genetics distributions of these two polymorphisms in Asians and Caucasians. Another possible explanation of this phenomenon is that genetic associations between TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC may also be influenced by gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions, but the extent of impact of gene–gene and gene–environmental interactions on genetic association between TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC in different ethnicities may be different.

As for evaluation of heterogeneities, obvious between-study heterogeneities were detected for -308 G/A polymorphisms in certain comparisons (data not shown). In further stratified analyses, a great reduction in heterogeneity was found in the Asian subgroup. However, the reduction tendency of heterogeneity in Caucasians was not obvious. These findings suggested that differences in ethnic background could partially explain observed heterogeneities between studies.

As with all meta-analysis, the present study certainly has some limitations. First, our results were based on unadjusted estimations due to lack of raw data, and failure to perform further stratified analyses according to age, gender and co-morbidity conditions may affect the reliability of our findings [34,35]. Second, only case-control studies were included in this meta-analysis, and thus our findings may also be influenced by potential selection bias [35,36]. Third, associations between TNF-α polymorphisms and CRC may also be influenced by gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions. However, the majority of studies did not consider these potential interactions, which impeded us to perform relevant analyses accordingly [37,38]. Taken these limitations into consideration, the results of the current study should be interpreted with caution.

Overall, our meta-analysis suggested that TNF-α -238 G/A polymorphism may serve as a potential biological marker for CRC in Caucasians, and TNF-α -308 G/A polymorphism may serve as a potential biological marker for CRC in Asians. However, further well-designed studies are warranted to confirm our findings. Additionally, future investigations are needed to explore potential roles of other TNF-α polymorphisms in the development of CRC.

Abbreviations

- CI

95% confidence interval

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- OR

odds ratio

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Author Contribution

Xue Huang and Haixing Jiang conceived of the study and participated in its design. Xue Huang and Shanyu Qin conducted the systematic literature review. Yongru Liu and Lin Tao performed data analyses. Xue Huang and Shanyu Qin drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel R., Ma J., Zou Z. and Jemal A. (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 64, 9–29 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M.. et al. (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359–E386 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang P.S., Chen T.Y. and Giovannucci E. (2009) Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 124, 2406–2415 10.1002/ijc.24191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedirko V., Tramacere I., Bagnardi V., Rota M., Scotti L., Islami F.. et al. (2011) Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann. Oncol. 22, 1958–1972 10.1093/annonc/mdq653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan D.S., Lau R., Aune D., Vieira R., Greenwood D.C., Kampman E.. et al. (2011) Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 6, e20456 10.1371/journal.pone.0020456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner H., Kloor M. and Pox C.P. (2014) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 383, 1490–1502 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coşkun Ö, Öztopuz Ö and Özkan ÖF (2017) Determination of IL-6, TNF-α and VEGF levels in the serums of patients with colorectal cancer. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 63, 97–101 10.14715/cmb/2017.63.5.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang P.H., Pan Y.P., Fan C.W., Tseng W.K., Huang J.S., Wu T.H.. et al. (2016) Pretreatment serum interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels predict the progression of colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 5, 426–433 10.1002/cam4.602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanilov N., Miteva L., Dobreva Z. and Stanilova S. (2014) Colorectal cancer severity and survival in correlation with tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 28, 911–917 10.1080/13102818.2014.965047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banday M.Z., Balkhi H.M., Hamid Z., Sameer A.S., Chowdri N.A. and Haq E. (2016) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) -308G/A promoter polymorphism in colorectal cancer in ethnic Kashmiri population – a case control study in a detailed perspective. Meta Gene 9, 128–136 10.1016/j.mgene.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basavaraju U., Shebl F.M., Palmer A.J., Berry S., Hold G.L., El-Omar E.M.. et al. (2015) Cytokine gene polymorphisms, cytokine levels and the risk of colorectal neoplasia in a screened population of Northeast Scotland. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 24, 296–304 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burada F., Dumitrescu T., Nicoli R., Ciurea M.E., Rogoveanu I. and Ioana M. (2013) Cytokine promoter polymorphisms and risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Lab. 59, 773–779 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2012.120713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity-Park M.M., Loftus E.V. Jr, Bryant S.C., Sandborn W.J. and Smyrk T.C. (2008) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms in ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 407–415 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunter M.J., Canzian F., Landi S., Chanock S.J., Sinha R. and Rothman N. (2006) Inflammation-related gene polymorphisms and colorectal adenoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1126–1131 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrity-Park M.M., Loftus E.V. Jr, Bryant S.C., Sandborn W.J. and Smyrk T.C. (2008) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms in ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 407–415 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamadien M.A., Khan Z., Vaali-Mohammed M.A., Zubaidi A., Al-Khayal K., McKerrow J.. et al. (2016) Polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor alpha in Middle Eastern population with colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 37, 5529–5537 10.1007/s13277-015-4421-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang W.H., Yang Y.I., Yea S.S., Lee Y.J., Chun J.H., Kim H.I.. et al. (2001) The -238 tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter polymorphism is associated with decreased susceptibility to cancers. Cancer Lett. 166, 41–46 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00438-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapitanović S., Čačev T., Catela Ivković T., Lončar B. and Aralica G. (2014) TNFα gene/protein in tumorigenesis of sporadic colon adenocarcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 97, 285–291 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landi S., Moreno V., Gioia-Patricola L., Guino E., Navarro M., de Oca J.. et al. (2003) Association of common polymorphisms in inflammatory genes interleukin (IL)6, IL8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, NFKB1, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 63, 3560–3566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landi S., Gemignani F., Bottari F., Gioia-Patricola L., Guino E., Cambray M.. et al. (2006) Polymorphisms within inflammatory genes and colorectal cancer. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 5, 15 10.1186/1477-5751-5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M., You Q. and Wang X. (2011) Association between polymorphism of the tumor necrosis factor alpha-308 gene promoter and colon cancer in the Chinese population. Genet. Test Mol. Biomarkers 15, 743–747 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z., Li S.A., Sun Y., Liu Y., Li W.L., Yang L.. et al. (2017) TNF-α -308 A allele is associated with an increased risk of distant metastasis in rectal cancer patients from Southwestern China. PLoS One 12, e0178218 10.1371/journal.pone.0178218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macarthur M., Sharp L., Hold G.L., Little J. and El-Omar E.M. (2005) The role of cytokine gene polymorphisms in colorectal cancer and their interaction with aspirin use in the northeast of Scotland. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 14, 1613–1618 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madani S., Noorinayer B., Madani H., Sadrolhefazi B., Molanayee S., Bakayev V.. et al. (2008) No association between TNF-alpha-238 polymorphism and colorectal cancer in Iranian patients. Acta Oncol. 47, 473–474 10.1080/02841860701491694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park K.S., Mok J.W., Rho S.A. and Kim J.C. (1998) Analysis of TNFB and TNFA NcoI RFLP in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cells 8, 246–249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanilov N., Miteva L., Dobreva Z. and Stanilova S. (2014) Colorectal cancer severity and survival in correlation with tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 28, 911–917 10.1080/13102818.2014.965047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suchy J., Kłujszo-Grabowska E., Kładny J., Cybulski C., Wokołorczyk D., Szymańska-Pasternak J.. et al. (2008) Inflammatory response gene polymorphisms and their relationship with colorectal cancer risk. BMC Cancer 8, 112 10.1186/1471-2407-8-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theodoropoulos G., Papaconstantinou I., Felekouras E., Nikiteas N., Karakitsos P., Panoussopoulos D.. et al. (2006) Relation between common polymorphisms in genes related to inflammatory responseand colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 5037–5043 10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tóth E.K., Kocsis J., Madaras B., Bíró A., Pocsai Z., Fust G.. et al. (2007) The 8.1 ancestral MHC haplotype is strongly associated with colorectal cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 121, 1744–1748 10.1002/ijc.22922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsilidis K.K., Helzlsouer K.J., Smith M.W., Grinberg V., Hoffman-Bolton J., Clipp S.L.. et al. (2009) Association of common polymorphisms in IL10, and in other genes related to inflammatory response and obesity with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 20, 1739–1751 10.1007/s10552-009-9427-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang A., Zhu Z., Jia H., Jia X., He X. and Zhu G. (2008) Association of TNF gene polymorphism with colorectal cancer risk. J. Tongji Univ. 29, 24–27 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. and Altman D.G.. PRISMA group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stang A. (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie X., Shi X. and Liu M. (2017) The roles of TLR gene polymorphisms in atherosclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 35,317 subjects. Scand. J. Immunol. 86, 50–58 10.1111/sji.12560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie X., Shi X., Xun X. and Rao L. (2017) Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene single nucleotide polymorphisms and the risk of hypertension: a meta-analysis involving 63,258 subjects. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 39, 175–182 10.1080/10641963.2016.1235177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min L., Chen D., Qu L. and Shou C. (2014) Tumor necrosis factor-a polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 9, e85187 10.1371/journal.pone.0085187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y., Cheng J., Guo X., Mo J., Gao B., Zhou H.. et al. (2018) The roles of PAI-1 gene polymorphisms in atherosclerotic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 149,908 subjects. Gene 673, 167–173 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y., Xu Y., Wang Y., Yao Y. and Yang J. (2018) Associations between interleukin gene polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 10.1111/1440-1681.13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]