Abstract

Introduction: F-box proteins are the substrate-recognizing subunits of SKP1 (S-phase kinase-associated protein 1)–cullin1–F-box protein (SCF) E3 ligase complexes that play pivotal roles in multiple cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Dysregulation of F-box proteins may lead to an unbalanced proteolysis of numerous protein substrates, contributing to progression of human malignancies. However, the prognostic values of F-box members, especially at mRNA levels, in breast cancer (BC) are elusive. Methods: An online database, which is constructed based on the gene expression data and survival information downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), was used to investigate the prognostic values of 15 members of F-box mRNA expression in BC. Results: We found that higher mRNA expression levels of FBXO1, FBXO31, SKP2, and FBXO5 were significantly associated with worse prognosis for BC patients. While FBXO4 and β-TrCP1 were found to be correlated to better overall survival (OS). Conclusion: The associated results provide new insights into F-box members in the development and progression of BC. Further researches to explore the F-box protein-targetting reagents for treating BC are needed.

Keywords: breast cancer, F-box, literature review, prognostic value

Introduction

Ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) governs diverse cellular processes such as cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, transcription, and apoptosis through targetting specific substrate proteins for ubiquitylation and degradation. The ubiquitin-activating E1 enzyme, ubiquitin–conjugating E2 enzyme and ubiquitin-protein E3 ligase exert the multistep enzymatic processes to catalyze the ubiquitinated substrates. The SKP1–cullin1–F-box protein (SCF) E3 ligase complex, which is composed of the invariant components S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1), the E3 ligase RBX1 (also known as ROC1) and cullin 1, as well as variable F-box proteins [1], is so far the best characterized E3 ligase family member [2]. The F-box proteins are able to bind to a distinct subset of substrates though its WD40 or leucine-rich domains and determine the substrate specificity of SCF complex [3]. Until now, 69 mammalian F-box proteins have been identified, they can be organized into three subclasses [4]: (i) the well-studied β-TRCP1, FBXW7 (also known as Fbw7, Sel-10, hCdc4, or hAgo), and β-TRCP2 (also known as FBXW11), which contain WD40 repeat domains; (ii) FBXL family members, including SKP2 (also known as FBXL1), which contain leucine-rich repeat domains; and (iii) FBXO proteins. Owing to the pivotal and indispensable roles in cell cycle regulation that have been identified, the relationship between these proteins and tumorigenesis attract much attention [5].

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignant disease that causes the most cancer-related deaths amongst females worldwide [6]. According to the expression patterns of hormone and growth factor receptors, BCs are classified into four major molecular subtypes: luminal A and B, HER2-like, and basal-like. Due to the heterogeneous and high morbidity of disease, the death rates of BC remain high [7]. Therefore, the detailed molecular mechanism underlying the BC development and progression is important to be explored, and it is essential to identify novel targets for predicting or treating BCs. Amongst the 69 F-box proteins, only four members—FBXW7, SKP2, β-TrCP1, and β-TrCP2—have been extensively studied, and 15 of them are so far identified to play determined roles in cancers and they are grouped into four categories: tumor suppressive, oncogenic, context-dependent, or undetermined functions in cancer [4]. Nevertheless, the prognostic values of each individual F-box proteins, specially at the mRNA level in BCs are still elusive.

Kaplan–Meier plotter (KM plotter) database is constructed based on the gene expression data and survival information downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [8]. Owing to its ease of access to database, this online survival analysis tool has been widely used to analyze the prognostic values of individual genes in lung cancer, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, and BC [9–12]. In the present study, we selected 15 well-identified members of F-box family to assess their prognostic values for BC. The relationship between F-box mRNA expression and clinical characteristics were also analyzed by KM plotter database.

Materials and methods

An online KM plotter database [8] was used to assess the prognostic values of 15 F-box members’ mRNA expression in BC as previously described [11]. The background database of this online survival analysis tool was established using gene expression data and survival information of 1809 patients (1402 BC patients with overall survival (OS) data) downloaded from GEO (Affymetrix HGU133A and HGU133+2 microarrays) [8]. These two microarrays are frequently used because these two arrays contain 22277 probe sets at nearly identical platforms. An overview of the clinical data is presented in Table 1 [13–25]. Each of 15 individual members of F-box members were entered into this online analysis database respectively (http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=breast), and Kaplan–Meier survival curves were acquired. Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and log rank P-values were also obtained on the webpages, and P-values of <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the microarray datasets used in the analysis.

| GEO ID | Platform | Number of patients | Age (years) | Tumor size (cm) | ER+ | Lymph node+ | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Relapse event | Average relapase-free survival | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE12276 | GPL570 | 204 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 204 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | Bos et al. (2009) |

| GSE16391 | GPL570 | 55 | 61 ± 9 | NA | 55 | 33 | 2 | 35 | 18 | 55 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | Desmedt et al. (2009) |

| GSE12093 | GPL96 | 136 | NA | NA | 136 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | Zhang et al. (2009) |

| GSE11121 | GPL96 | 200 | NA | 2.1 ± 1 | NA | 0 | 58 | 136 | 35 | 46 | 7.8 ± 4.2 | Schmidt et al. (2008) |

| GSE9195 | GPL570 | 77 | 64 ± 9 | 2.4 ± 1 | 77 | 36 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 13 | 7.8 ± 2.5 | Loi et al. (2008) |

| GSE7390 | GPL96 | 198 | 46 ± 7 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 134 | NA | 30 | 83 | 83 | 91 | 9.3 ± 5.6 | Desmedt et al. (2007) |

| GSE6532 | GPL96 | 82 | 64 ± 10 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 70 | 22 | 0 | 54 | 1 | 19 | 6.1 ± 3.1 | Loi et al. (2007) |

| GSE5327 | GPL96 | 58 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11 | 6.8 ± 3.1 | Minn et al. (2007) |

| GSE4922 | GPL96 | 1 | 69 | 2.2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.17 | Ivshina et al. (2006) |

| GSE2494 | GPL96 | 251 | 62 ± 14 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 213 | 84 | 67 | 128 | 54 | NA | NA | Miller et al. (2005) |

| GSE2990 | GPL96 | 102 | 58 ± 12 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 73 | 15 | 27 | 20 | 36 | 40 | 6.6 ± 3.9 | Sotirious et al. (2006) |

| GSE2034 | GPL96 | 286 | NA | NA | 209 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 107 | 6.5 ± 3.5 | Wang et al. (2005) |

| GSE1456 | GPL96 | 159 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 28 | 58 | 61 | 40 | 6.2 ± 2.3 | Pawitan et al. (2005) |

| Total | 1809 | 57 ± 13 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 968 | 190 | 227 | 534 | 312 | 646 | 6.4 ± 4.1 |

Results

Prognostic roles of F-box in all BC patients

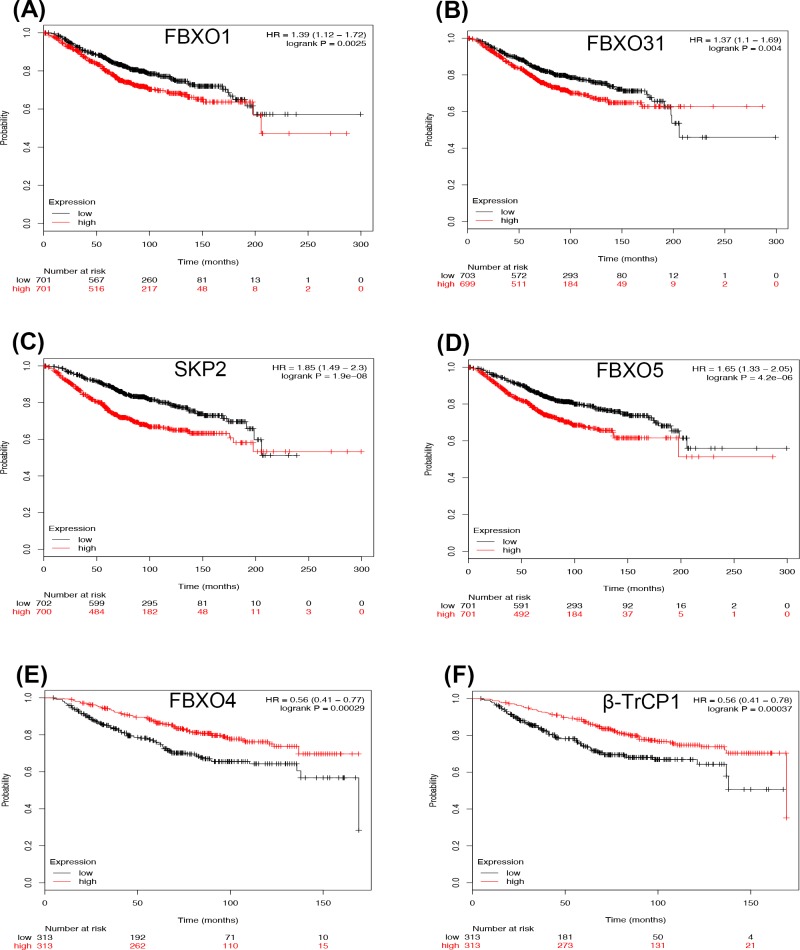

We first examined the prognostic effects of 15 members of F-box mRNA in all BC patients by KM plotter database. As shown in Figure 1, FBXO1 (HR = 1.39 95%CI: 1.12–1.72, P=0.0025), FBXO31 (HR = 1.37 95%CI: 1.10–1.69, P=0.0040), SKP2 (HR = 1.85 95%CI: 1.49–2.30, P=0.0008), and FBXO5 (HR = 1.65 95%CI: 1.33–2.05, P=0.0004) were significantly associated with worse OS in all BC patients (Figure 1A–D). However, FBXO4 (HR = 0.56 95%CI: 0.41–0.77, P=0.0003) and β-TrCP1 (HR = 0.73 95%CI: 0.59–0.90, P=0.0034) were associated with better prognosis (Figure 1E,F). The mRNA expression levels of FBXW8, FBXL3, FBXO10, FBXO11, FBXO18, FBXO9, β-TrCP2, and FBXL10 were not correlated with OS in all BC patients (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. The prognostic values of the mRNA expression of F-box in all BCs.

Overexpression of FBXO1 (A), FBXO31 (B), SKP2 (C), and FBXO5 (D) are significantly associated with worse OS in all BC patients. Overexpression of FBXO4 (E) and β-TrCP1 (F) are associated with better prognosis.

Prognostic roles of F-box members in different BC subtypes

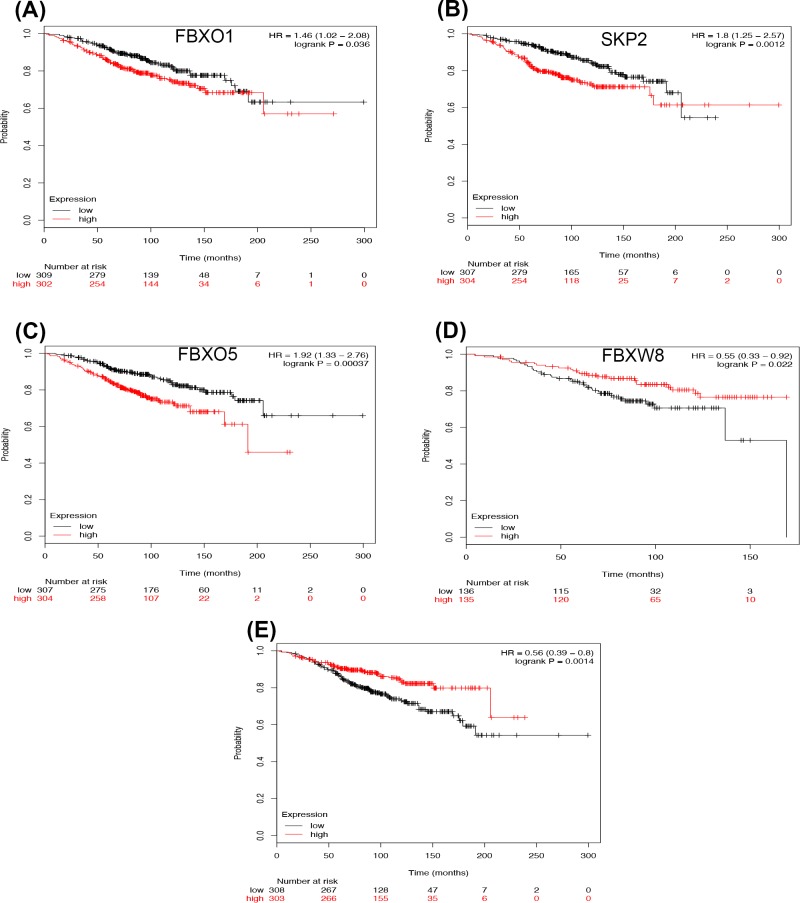

Then, we respectively assessed the prognostic effects of F-box in BCs with different intrinsic subtypes. For luminal A type BC patients, FBXO1 (HR = 1.46 95%CI: 1.02–2.08, P=0.0358), SKP2 (HR = 1.80 95%CI: 1.25-2.57, P=0.0012), and FBXO5 (HR = 1.92 95%CI: 1.33–2.76, P=0.0004) were correlated to worse survival (Figure 2A–C). Whereas FBXW8 (HR = 0.55 95%CI: 0.33–0.92, P=0.0219) and β-TrCP1 (HR = 0.56 95%CI: 0.39–0.80, P=0.0014) were significantly associated with longer OS (Figure 2D,E). The rest members of F-box were not correlated to prognosis in luminal A type BC (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 2. The prognostic values of the mRNA expression of F-box in luminal A type BCs.

The high expression of FBXO1 (A), SKP2 (B), and FBXO5 (C) are correlated to worse survival, and FBXW8 (D) and β-TrCP1 (E) are associated with longer OS in luminal A type BC patients.

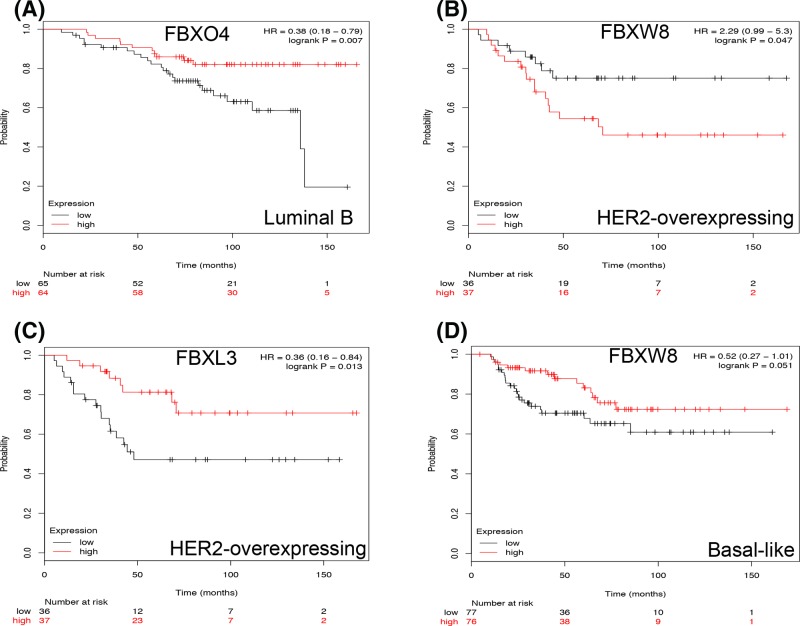

In luminal B type BC patients, only high mRNA expression of FBXO4 was significantly associated with better survival, the HR was 0.38 (95%CI: 0.18-0.79, P=0.0070, Figure 3A). The remaining F-box members did not show any prognostic value in luminal B type BC patients (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3. The prognostic values of some selected F-box in luminal B type, HER2-expressing or Basal-like BCs.

Survival curves of FBXO4 (A) are plotted for luminal B type BC patients. Survival curves of FBXW8 (B) and FBXL3 (C) are plotted for HER2-overexpressing BC patients. Survival curves of FBXW8 (D) are plotted for basal-like BC patients.

In HER2-overexpressing BC, high mRNA expression of FBXW8 was associated with poor prognosis, the HR was 2.29 (95%CI: 0.99, 5.30), P=0.0475 (Figure 3B). However, FBXL3 (HR = 0.36, 95%CI: 0.16–0.84, P=0.0134) was significantly associated with better OS (Figure 3C). The rest of F-box members were not associated with prognosis in HER2-overexpressing BC patients (Supplementary Figure S4).

With regard to basal-like BC, none of the selected F-box members was associated with prognosis (Supplementary Figure S5). Only FBXW8 (HR = 0.52, 95%CI: 0.27–1.01, P=0.051) was modestly associated with better prognosis (Figure 3D).

Prognostic roles of F-box members in BC patients with different status of TP53

Furthermore, we assessed prognostic values of F-box members in BCs with different status of TP53. As shown in Table 2, only SKP2 (HR = 1.79, 95%CI: 0.92–3.49, P=0.0809) was modestly associated with worse survival for wild-TP53-type BCs, the other F-box members were not correlated with prognosis. In mutant-TP53-type BC, FBXL3 was significantly associated with longer OS, however, the other F-box members did not show any prognostic values.

Table 2. The association between the F-box members and the prognosis of BC with different p53 status.

| F-box family | Affymetrix IDs | p53 | HR | 95%CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | 229419_at | Mutant | 1.99 | (0.50, 7.98) | 0.3193 |

| Wild | / | / | / | ||

| FBXO4 | 223493_at | Mutant | 1.20 | (0.32, 4.48) | 0.7888 |

| Wild | / | / | 1.88)/ | ||

| FBXW8 | 231883_at | Mutant | 1.01 | (0.26, 3.90) | 0.9886 |

| Wild | / | / | / | ||

| FBXL3 | 225132_at | Mutant | 0.11 | (0.01, 0.91) | 0.0136 |

| Wild | 1.28 | (0.55, 3.01) | 0.5648 | ||

| FBXO1 | 204826_at | Mutant | 0.94 | (0.44, 2.01) | 0.8786 |

| Wild | 0.87 | (0.46, 1.66) | 0.6758 | ||

| FBXO10 | 227222_at | Mutant | 0.83 | (0.22, 3.07) | 0.7745 |

| Wild | / | / | / | ||

| FBXO11 | 222119_s_at | Mutant | 0.83 | (0.38, 1.82) | 0.6423 |

| Wild | 0.57 | (0.29, 1.12) | 0.1004 | ||

| FBXO18 | 224683_at | Mutant | 0.50 | (0.13, 2.02) | 0.3248 |

| Wild | / | / | / | ||

| FBXO31 | 219785_s_at | Mutant | 0.53 | (0.24, 1.19) | 0.1201 |

| Wild | 0.98 | (0.51, 1.86) | 0.9411 | ||

| SKP2 | 203625_at | Mutant | 0.70 | (0.33, 1.52) | 0.3681 |

| Wild | 1.79 | (0.92, 3.49) | 0.0809 | ||

| FBXO5 | 218875_at | Mutant | 1.02 | (0.46, 2.27) | 0.9562 |

| Wild | 1.24 | (0.92, 3.49) | 0.0809 | ||

| FBXO9 | 238472_at | Mutant | 1.93 | (0.48, 7.73) | 0.3471 |

| Wild | / | / | / | ||

| β-TrCP1 | 216091_s_at | Mutant | 1.47 | (0.63, 3.43) | 0.3684 |

| Wild | 1.01 | (0.53, 1.92) | 0.9799 | ||

| β-TrCP2 | 209455_at | Mutant | 0.79 | (0.37, 1.71) | 0.5514 |

| Wild | 1.52 | (0.79, 2.92) | 0.2037 | ||

| FBXL10 | 226215_s_at | Mutant | 1.43 | (0.38, 5.41) | 0.6004 |

| Wild | / | / | / |

Prognostic roles of F-box members in BC patients with different pathological grades

Next, we assessed prognostic values of F-box members in different pathological grade BCs. We could see from the Table 3 that none of the F-box members was found to be associated with prognosis in grade I BC patients. While in grade II BC, FBXW7 (HR = 0.27, 95%CI: 0.07–1.02, P=0.0383) was correlated with better OS, FBXO1 (HR = 2.10, 95%CI: 1.34–3.30, P=0.0001) and SKP2 (HR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.01–2.40, P=0.0420) were significantly associated with poor survival. However, the higher mRNA expression of FBXO4 (HR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.35-0.99, P=0.0430) and FXBL3 (HR = 0.52, 95%CI: 0.31–0.88, P=0.0136) were associated with better survival for grade III BCs.

Table 3. Correlation of F-box with different pathological grade status of BC patients.

| F-box family | Affymetrix IDs | Grades | HR | 95%CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | 229419_at | I | 0.57 | (0.05, 6.27) | 0.6390 |

| II | 0.27 | (0.07, 1.02) | 0.0383* | ||

| III | 1.32 | (0.79, 2.21) | 0.2833 | ||

| FBXO4 | 223493_at | I | 1.66 | (0.15, 18.35) | 0.6780 |

| II | 1.10 | (0.35, 3.48) | 0.8711 | ||

| III | 0.59 | (0.35, 0.99) | 0.0430* | ||

| FBXW8 | 231883_at | I | 0.26 | (0.02, 3.57) | 0.2910 |

| II | 0.94 | (0.30, 2.92) | 0.9179 | ||

| III | 0.79 | (0.48, 1.32) | 0.3707 | ||

| FBXL3 | 225132_at | I | 2.02 | (0.18, 22.59) | 0.5610 |

| II | 0.80 | (0.25, 2.51) | 0.6973 | ||

| III | 0.52 | (0.31, 0.88) | 0.0136* | ||

| FBXO1 | 225132_at | I | 0.73 | (0.28, 1.87) | 0.5070 |

| II | 2.10 | (1.34, 3.30) | 0.0001* | ||

| III | 0.91 | (0.66, 1.27) | 0.5884 | ||

| FBXO10 | 227222_at | I | 0.44 | (0.04, 4.86) | 0.4900 |

| II | 0.87 | (0.28, 2.70) | 0.8039 | ||

| III | 1.58 | (0.95, 2.64) | 0.0768 | ||

| FBXO11 | 222119_s_at | I | 0.66 | (0.26, 1.67) | 0.3750 |

| II | 0.89 | (0.58, 1.38) | 0.6109 | ||

| III | 1.37 | (0.98, 1.91) | 0.0628 | ||

| FBXO18 | 224683_at | I | 1.76 | (0.16, 19.53) | 0.6390 |

| II | 0.59 | (0.18, 1.97) | 0.3872 | ||

| III | 0.81 | (0.49, 1.36) | 0.4288 | ||

| FBXO31 | 219785_s_at | I | 1.11 | (0.45, 2.76) | 0.8187 |

| II | 1.22 | (0.79, 1.87) | 0.3661 | ||

| III | 1.32 | (0.95, 1.83) | 0.0953 | ||

| SKP2 | 203625_at | I | 1.59 | (0.65, 3.92) | 0.3078 |

| II | 1.56 | (1.01, 2.40) | 0.0420* | ||

| III | 1.01 | (0.73, 1.40) | 0.9648 | ||

| FBXO5 | 218875_s_at | I | 1.65 | (0.67, 4.07) | 0.2727 |

| II | 1.41 | (0.92, 2.17) | 0.1110 | ||

| III | 1.38 | (0.99, 1.91) | 0.0570 | ||

| FBXO9 | 238472_at | I | 0.57 | (0.05, 6.27) | 0.6390 |

| II | 1.91 | (0.58, 6.37) | 0.2812 | ||

| III | 0.98 | (0.58, 1.65) | 0.9426 | ||

| β-TrCP1 | 216091_s_at | I | 0.60 | (0.24, 1.51) | 0.2719 |

| II | 1.01 | (0.66, 1.55) | 0.9678 | ||

| III | 0.84 | (0.60, 1.16) | 0.2890 | ||

| β-TrCP2 | 209455_at | I | 0.88 | (0.35, 2.20) | 0.7763 |

| II | 1.04 | (0.68, 1.59) | 0.8656 | ||

| III | 1.30 | (0.94, 1.81) | 0.1155 | ||

| FBXL10 | 226215_s_at | I | 0.50 | (0.04, 5.54) | 0.5610 |

| II | 0.51 | (0.15, 1.70) | 0.2661 | ||

| III | 0.66 | (0.39, 1.11) | 0.1146 |

Discussion

F-box protein is one of the core components of SCF multisubunit E3 ligase complex, it determines the substrate specificity of SCF complex by binding to substrates through WD40 or leucine-rich domains [3]. F-box family members are divided into three subclasses, including 10 FBXW proteins, 22 FBXL proteins, and 37 FBXO proteins. F-box proteins are implicated in multiple cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and invasion via mediating degradation of numerous substrates [4]. In this study, by using an online survival analysis tool, we found that high mRNA expression of FBXO4 and β-TrCP1 were associated with better outcome for BCs, and FBXO1, FBXO31, FBXO5, and SKP2 were significantly correlated to worse prognosis.

FBXO4 is generally identified as a tumor suppressor, FBXO4-deficient mice will develop highly aggressive melanomas, as well as lymphomas, histolytic sarcomas, mammary and hepatocellular carcinomas [26,27]. Mutation or loss of FBXO4 impairs the dimerization of the SCFFbx4 ligase, resulting in accumulation of nuclear cyclin D1 and oncogenic transformation [28–30]. However, how FBXO4 determinates the cell fates of BC cells is unclear. We searched the Pubmed database and did not find any articles on the relationship between FBXO4 and BC. Hence, we used the KM plotter database to analyze the prognostic effect of FBXO4 in BC and found that high mRNA expression of FBXO4 was associated with longer OS for all BC patients. Additionally, high FBXO4 mRNA expression was correlated to better survival in luminal B and grade III BC patients.

β-TRCP1 and β-TRCP2 either exert their oncogenic or tumor suppressive roles depending on the specific cellular context(s). Interestingly, female mice with β-TRCP1−/− mammary glands exhibited hypoplastic phenotypes, which suggested that β-TRCP1 was critical for tissue development [31]. β-TRCP1 was significantly up-regulated in prostate cancer and hepatoblastoma [32], and high expression of β-TRCP1 at both mRNA and protein levels in colorectal cancer were correlated with poor clinical prognosis [33]. However, in gastric cancers, somatic mutation of β-TRCP1, which impaired ligase activity, contributed to tumor development and progression through β-catenin stabilization [34]. In TNBC cells, knockdown of β-TRCP1 reduced the cell proliferative ability [35], implicating a tumor suppressive role of β-TRCP1 in BC. Here, we showed that high mRNA expression of β-TRCP1 was associated with longer OS in luminal A type BC or all BC patients. On the other hand, β-TRCP2 also has tumor type-dependent roles in dominating tumorigenesis. Overexpression of β-TRCP2 was observed in a variety of human cancers, including prostate, breast, and gastric cancers [36]. Whereas mutation of β-TRCP2 in gastric cancer caused β-catenin accumulation, and contributed to carcinogenesis by activating WNT signaling pathway [37]. Inhibition of β-TRCP2 by miR-106b-25 cluster in non-small lung cancer cells promoted cell invasion and metastasis [38]. However, β-TRCP2 was not associated with prognosis in BC patients according to the current results analyzed by KM plotter database.

FBXO1, also known as cyclin F, meditates centrosome duplication and is critical for maintaining genome integrity, thus it has been regarded as an emerging tumor suppresser [39]. Knockout FBXO1 in MEFs leads to cell cycle defects [40]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, FBXO1 was down-regulated and low expression levels of FBXO1 were significantly associated with worse clinical characteristics and poorer prognosis [41]. Unexpectedly, we suggested an uncanonical function of FBXO1 exerted in BC, as we showed that high mRNA expression levels of FBXO1 were associated with worse survival in BC patients.

FBXO31 was regarded as an emerging tumor suppressor, which is often down-regulated in several human cancers, including BC, gastric cancer, and hepatocellular cancer [42–44]. FBXO31 was involved in DNA damage response for maintaining genomic stability. After DNA damage induced by genotoxic agents or γ-irradiation, phosphorylation of FBXO31 was increased immediately [45], then SCF/FBXO31 promoted MDM2 ubiquitination, resulting in accumulation of p53 and growth arrest [46]. Overexpression of FBXO31 in cancer cells inhibited cell growth and colon formation, and ectopic expression of FBXO31 significantly decreased tumor formation in xenograft nude mice [42–44]. However, overexpression of FBXO31 in lung cancer promoted cell growth and metastasis [47], and higher expression levels of FBXO31 predicted worse survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [48]. Therefore, FBXO31 may also exert its role in tumorigenesis depending on tumor cell types. In our study, we used the KM plotter database to reveal that higher expression of FBXO31 mRNA was associated with poorer prognosis in BC patients.

The F-box protein SKP2 plays an oncogenic role in human cancers. Mechanistically, SKP2 facilitates ubiquitination and degradation of many tumor suppressors, such as p21, p27, p57, FOXO1, and others [2]. Furthermore, SKP2 enhances DNA damage response and promotes DNA double-strand break repair pathways in cancer cells [49]. As a result, SKP2 is up-regulated in several human cancers, including colorectal cancer [50], bladder cancer [51], BC [52,53], melanoma [54], prostate cancer [55], hepatocellular cancer [56], cervical cancer [49], and lymphoma [57]. In BC, SKP2 has been reported to correlate to poorer prognosis [58–60]. Additionally, immunohistochemical analysis indicated that overexpression of SKP2 were more frequently observed in ER-negative BC [53,59]. In our study, the higher expression of SKP2 mRNA was significantly associated with shorter OS in luminal A type BC patients. Previous results have indicated that SKP2 expression was associated with higher tumor grade in BCs or bladder cancers [51,59,60]. Interestingly, we showed that high mRNA expression of SKP2 was correlated to poor prognosis in grade II BC patients, but not in grade I or grade III BC patients.

FBXO5 is also suggested to play an emerging oncogenic role in human cancers. FBXO5 functions as an endogenous inhibitor of APC/C, which results in the stabilization of APC/C ubiquitin substrates, such as cyclin A, cylcin B, or Secure [61]. Up-regulation of FBXO5 in p53-deficient cells could promote cell proliferation, tetraploidy, and genomic instability [62]. By analysis of more than 1600 benign and malignant tumors, Lehman et al. [61] suggested that FBXO5 was strongly overexpressed in malignant tumors, rather than in benign tumors. Furthermore, overexpression of FBXO5 was associated with poor outcome in ovarian cancer [63], prostate cancer [64], and hepatocellular carcinoma [65]. In BC patients, overexpression of FBXO5 was significantly correlated with histologic grade and prognosis [66]. Consistently, our results demonstrated that FBXO5 had an oncogenic role in BC, higher expression of FBXO5 in mRNA level was significantly associated with poorer survival, especially in luminal A type BC patients.

FBXO11 was able to inhibit tumor cell growth and induced cell death by target BCL-6 for degradation [67], and deletion or mutation of FBXO11 in pancreatic cancer patients was associated with poor prognosis [68]. In BCs, FBXO11 restrained tumor initiation and metastasis by promoting SNAIL ubiquitylation and degradation, and overexpression of FBXO11 was correlated with longer metastasis-free survival [69,70]. However, our results did not find any relationship between the FBXO11 mRNA expression and OS in BC.

FBXW8 forms a functional E3 ligase complex with cullin 7 to exert a tumor suppressive role [4]. Ectopic expression of FBXW8 in choriocarcinoma JEG-3 cells increased the percentage of cells at S-phase and decreased the percentage of G2/M-phase cells [71], suggesting that FBXW8 was critical for cell growth. As FBXW8-meditated cyclin D1 and HPK1 degradation was necessary for cancer cell growth [71,72]. However, there is still no result about the prognostic role of FBXW8 in BC. Our results indicated that overexpression of FBXW8 mRNA was significantly associated with better prognosis in luminal A and basal-like BC patients, however, it was correlated with worse survival in HER2-overexpressiong BC patients.

An accumulation of pathological data have been proved that FBXW7 is a tumor suppressor by targetting various oncogenic proteins, such as Notch, cyclin E, c-Myc, and c-Jun, for degradation [73,74]. Interestingly, FBXW7 expressed in the host microenvironment also suppressed cancer metastasis depending on the FBXW7/NOTCH/CCL2 axis [75]. Hence, FBXW7 mutation, resulting in loss-of-function of FBXW7, was frequently observed amongst primary human cancers. Approximately 6% of human cancers were FBXW7 mutated, and 9% of primary endometrial cancers were FBXW7 mutated [76]. Reduced expression of FBXW7 has been reported to be correlated with worse outcomes in several human cancers, including gastric cancer [77], colorectal cancer [78], cervical squamous carcinoma [79], glioma [80], and prostate cancer [81]. For BCs, FBXW7 was significantly down-regulated, knockdown of FBXW7 in BC cells promoted cell proliferation, migration, and inhibited cell apoptosis [82,83]. Inactivation of FBXW7 by promoter-specific methylation was correlated with poorly differentiated BC [84]. FBXW7 mRNA expression was reduced in BC patients with high histological grade and hormone receptor-negative tumors [85]. A meta-analysis including 1900 patients indicated that the prognostic value of FBXW7 at mRNA level in BC was depending on ER status and molecular subtypes [86]. According to our results, increased mRNA expression of FBXW7 was associated with better OS only in grade II BC patients.

Amongst the large family members of F-box, only few members have been extensively studied. Here, we used the KM plotter database to assess the prognostic values of the selected 15 members of F-box mRNA expression in BC and demonstrated that FBXO1, FBXO31, SKP2, and FBXO5 were significantly associated with worse prognosis in BC patients. FBXO4 and β-TrCP1 were found to be correlated to better OS. These associated results provide new insights into F-box members in the development and progression of BC. Further studies are needed in order to get detailed understanding of functional characterization of each F-box member and determine whether they can be potential treatment targets of BC.

Supporting information

supplementary Figure S1.

supplementary Figure S2.

supplementary Figure S3.

supplementary Figure S4.

supplementary Figure S5.

Abbreviations

- APC/C

anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome

- β-TrCP1

β-transducin repeats containing proteins

- BC

breast cancer

- BCL-6

B-cell lymphoma 6 protein

- CCL2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CI

confidence interval

- FBXO3

F-box only protein 3

- GEO

gene expression omnibus

- HPK1

hematopoietic progenitor kinase1

- HR

hazard ratio

- KM plotter

Kaplan–Meier plotter

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- OS

overall survival

- SCFise

SKP1–cullin1–F-box protein

- SKP1

S-phase kinase-associated protein 1

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- WNT

wingless/integrated

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

Author contribution

X.W. and S.Z. conceived and designed the research. T.Z., J.S., and X.W. performed the experiments and anlyzed the data. S.Z. and X.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Deshaies R.J. (1999) SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 435–467 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frescas D. and Pagano M (2008) Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 438–449 10.1038/nrc2396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng N. et al. (2002) Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416, 703–709 10.1038/416703a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Liu P., Inuzuka H. and Wei W. (2014) Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 233–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakayama K.I. and Nakayama K (2005) Regulation of the cell cycle by SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 323–333 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W. et al. (2016) Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry D.A. et al. (2005) Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1784–1792 10.1056/NEJMoa050518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyorffy B. et al. (2010) An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 725–731 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X. et al. (2016) Prognostic values of four Notch receptor mRNA expression in gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 6, 28044 10.1038/srep28044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou X., Teng L. and Wang M (2016) Distinct prognostic values of four-Notch-receptor mRNA expression in ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 37, 6979–6985 10.1007/s13277-015-4594-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S. et al. (2017) Distinct prognostic values of S100 mRNA expression in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 39786 10.1038/srep39786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J. et al. (2016) Prognostic values of Notch receptors in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 37, 1871–1877 10.1007/s13277-015-3961-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bos P.D. et al. (2009) Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature 459, 1005–1009 10.1038/nature08021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desmedt C. et al. (2009) The Gene expression Grade Index: a potential predictor of relapse for endocrine-treated breast cancer patients in the BIG 1-98 trial. BMC Med. Genet. 2, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y. et al. (2009) The 76-gene signature defines high-risk patients that benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 116, 303–309 10.1007/s10549-008-0183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt M. et al. (2008) The humoral immune system has a key prognostic impact in node-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 5405–5413 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loi S. et al. (2008) Predicting prognosis using molecular profiling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. BMC Genomics 9, 239 10.1186/1471-2164-9-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desmedt C. et al. (2007) Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3207–3214 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loi S. et al. (2007) Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 1239–1246 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minn A.J. et al. (2007) Lung metastasis genes couple breast tumor size and metastatic spread. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6740–6745 10.1073/pnas.0701138104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivshina A.V. et al. (2006) Genetic reclassification of histologic grade delineates new clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 10292–10301 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller L.D. et al. (2005) An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13550–13555 10.1073/pnas.0506230102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sotiriou C. et al. (2006) Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98, 262–272 10.1093/jnci/djj052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y. et al. (2005) Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet 365, 671–679 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70933-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawitan Y. et al. (2005) Gene expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from adjuvant therapy: derived and validated in two population-based cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. 7, R953–R964 10.1186/bcr1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee E.K. et al. (2013) The FBXO4 tumor suppressor functions as a barrier to BRAFV600E-dependent metastatic melanoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 4422–4433 10.1128/MCB.00706-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaites L.P. et al. (2011) The Fbx4 tumor suppressor regulates cyclin D1 accumulation and prevents neoplastic transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 4513–4523 10.1128/MCB.05733-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbash O. et al. (2008) Mutations in Fbx4 inhibit dimerization of the SCF(Fbx4) ligase and contribute to cyclin D1 overexpression in human cancer. Cancer Cell 14, 68–78 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu X. et al. (2014) Alternative splicing variants of human Fbx4 disturb cyclin D1 proteolysis in human cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 447, 158–164 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lian Z. et al. (2015) FBXO4 loss facilitates carcinogen induced papilloma development in mice. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 750–755 10.1080/15384047.2015.1026512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama K. et al. (2003) Impaired degradation of inhibitory subunit of NF-kappa B (I kappa B) and beta-catenin as a result of targeted disruption of the beta-TrCP1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8752–8757 10.1073/pnas.1133216100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch A. et al. (2005) Elevated expression of Wnt antagonists is a common event in hepatoblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 4295–4304 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockwood W.W., Chandel S.K., Stewart G.L., Erdjument-Bromage H. and Beverly L.J. (2013) The novel ubiquitin ligase complex, SCF(Fbxw4), interacts with the COP9 signalosome in an F-box dependent manner, is mutated, lost and under-expressed in human cancers. PLoS ONE 8, e63610 10.1371/journal.pone.0063610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim C.J. et al. (2007) Somatic mutations of the beta-TrCP gene in gastric cancer. APMIS 115, 127–133 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yi Y.W. et al. (2015) beta-TrCP1 degradation is a novel action mechanism of PI3K/mTOR inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 47, e143 10.1038/emm.2014.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau A.W., Fukushima H. and Wei W. (2012) The Fbw7 and betaTRCP E3 ubiquitin ligases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Front. Biosci. (Landmark) Ed. 17, 2197–2212 10.2741/4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saitoh T. and Katoh M (2001) Expression profiles of betaTRCP1 and betaTRCP2, and mutation analysis of betaTRCP2 in gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 18, 959–964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savita U. and Karunagaran D (2013) MicroRNA-106b-25 cluster targets beta-TRCP2, increases the expression of Snail and enhances cell migration and invasion in H1299 (non small cell lung cancer) cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 841–847 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D’Angiolella V. et al. (2010) SCF(Cyclin F) controls centrosome homeostasis and mitotic fidelity through CP110 degradation. Nature 466, 138–142 10.1038/nature09140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tetzlaff M.T. et al. (2004) Cyclin F disruption compromises placental development and affects normal cell cycle execution. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2487–2498 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2487-2498.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu J. et al. (2013) Low cyclin F expression in hepatocellular carcinoma associates with poor differentiation and unfavorable prognosis. Cancer Sci. 104, 508–515 10.1111/cas.12100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar R. et al. (2005) FBXO31 is the chromosome 16q24.3 senescence gene, a candidate breast tumor suppressor, and a component of an SCF complex. Cancer Res. 65, 11304–11313 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H.L., Zheng W.L., Zhao R., Zhang B. and Ma W.L. (2010) FBXO31 is down-regulated and may function as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 24, 715–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X. et al. (2014) F-box protein FBXO31 is down-regulated in gastric cancer and negatively regulated by miR-17 and miR-20a. Oncotarget 5, 6178–6190 10.18632/oncotarget.2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santra M.K., Wajapeyee N. and Green M.R. (2009) F-box protein FBXO31 mediates cyclin D1 degradation to induce G1 arrest after DNA damage. Nature 459, 722–725 10.1038/nature08011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malonia S.K., Dutta P., Santra M.K. and Green M.R. (2015) F-box protein FBXO31 directs degradation of MDM2 to facilitate p53-mediated growth arrest following genotoxic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8632–8637 10.1073/pnas.1510929112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang H.L. et al. (2015) FBXO31 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and invasion in lung cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5, 1814–1822 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kogo R., Mimori K., Tanaka F., Komune S. and Mori M. (2011) FBXO31 determines poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 39, 155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu H.C. et al. (2016) Increased expression of SKP2 is an independent predictor of locoregional recurrence in cervical cancer via promoting DNA-damage response after irradiation. Oncotarget 7, 44047–44061 10.18632/oncotarget.10057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J.Q. et al. (2004) Correlation of Skp2 with carcinogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and prognosis in colorectal tumors. Int. J. Oncol. 25, 87–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elsherif E. et al. (2016) beta-catenin and SKP2 proteins as predictors of grade and stage of non-muscle invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 5, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radke S., Pirkmaier A. and Germain D. (2005) Differential expression of the F-box proteins Skp2 and Skp2B in breast cancer. Oncogene 24, 3448–3458 10.1038/sj.onc.1208328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng W.Q., Zheng J.M., Ma R., Meng F.F. and Ni C.R. (2005) Relationship between levels of Skp2 and P27 in breast carcinomas and possible role of Skp2 as targeted therapy. Steroids 70, 770–774 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rose A.E. et al. (2011) Clinical relevance of SKP2 alterations in metastatic melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 197–206 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00784.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Z. et al. (2012) Skp2: a novel potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1825, 11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu M. et al. (2009) The expression and prognosis of FOXO3a and Skp2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 15, 679–687 10.1007/s12253-009-9171-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seki R. et al. (2010) Prognostic significance of S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 and p27kip1 in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: effects of rituximab. Ann. Oncol. 21, 833–841 10.1093/annonc/mdp481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan C.H. et al. (2012) The Skp2-SCF E3 ligase regulates Akt ubiquitination, glycolysis, herceptin sensitivity, and tumorigenesis. Cell 149, 1098–1111 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang W. et al. (2016) Skp2 is over-expressed in breast cancer and promotes breast cancer cell proliferation. Cell Cycle 15, 1344–1351 10.1080/15384101.2016.1160986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang C. et al. (2015) High Skp2/low p57(Kip2) expression is associated with poor prognosis in human breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer 9, 13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsu J.Y., Reimann J.D., Sorensen C.S., Lukas J. and Jackson P.K. (2002) E2F-dependent accumulation of hEmi1 regulates S phase entry by inhibiting APC(Cdh1). Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 358–366 10.1038/ncb785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehman N.L., Verschuren E.W., Hsu J.Y., Cherry A.M. and Jackson P.K. (2006) Overexpression of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome inhibitor Emi1 leads to tetraploidy and genomic instability of p53-deficient cells. Cell Cycle 5, 1569–1573 10.4161/cc.5.14.2925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Min K.W. et al. (2013) Clear cell carcinomas of the ovary: a multi-institutional study of 129 cases in Korea with prognostic significance of Emi1 and Galectin-3. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 32, 3–14 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31825554e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang G. et al. (2002) Elevated Skp2 protein expression in human prostate cancer: association with loss of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and PTEN and with reduced recurrence-free survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 3419–3426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Y. et al. (2013) Early mitotic inhibitor-1, an anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome inhibitor, can control tumor cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with Skp2 stability and degradation of p27(Kip1). Hum. Pathol. 44, 365–373 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X. et al. (2013) The expression and prognosis of Emi1 and Skp2 in breast carcinoma: associated with PI3K/Akt pathway and cell proliferation. Med. Oncol. 30, 735 10.1007/s12032-013-0735-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duan S. et al. (2012) FBXO11 targets BCL6 for degradation and is inactivated in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Nature 481, 90–93 10.1038/nature10688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mann K.M. et al. (2012) Sleeping Beauty mutagenesis reveals cooperating mutations and pathways in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5934–5941 10.1073/pnas.1202490109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng H. et al. (2014) PKD1 phosphorylation-dependent degradation of SNAIL by SCF-FBXO11 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Cell 26, 358–373 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jin Y. et al. (2015) FBXO11 promotes ubiquitination of the Snail family of transcription factors in cancer progression and epidermal development. Cancer Lett. 362, 70–82 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Okabe H. et al. (2006) A critical role for FBXW8 and MAPK in cyclin D1 degradation and cancer cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 1, e128 10.1371/journal.pone.0000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H. et al. (2014) The CUL7/F-box and WD repeat domain containing 8 (CUL7/Fbxw8) ubiquitin ligase promotes degradation of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4009–4017 10.1074/jbc.M113.520106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welcker M and Clurman B.E. (2008) FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 83–93 10.1038/nrc2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akhoondi S. (2007) FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 9006–9012 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yumimoto K. et al. (2015) F-box protein FBXW7 inhibits cancer metastasis in a non-cell-autonomous manner. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 621–635 10.1172/JCI78782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calhuan E.S. et al. (2003) BRAF and FBXW7 (CDC4, FBW7, AGO, SEL10) mutations in distinct subsets of pancreatic cancer: potential therapeutic targets. Am. J. Pathol. 4, 1255–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokobori T. et al. (2009) p53-Altered FBXW7 expression determines poor prognosis in gastric cancer cases. Cancer Res. 69, 3788–3794 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Korphaisarn K. et al. (2017) FBXW7 missense mutation: a novel negative prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 39268–39279 10.18632/oncotarget.16848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu Y. et al. (2016) Loss of FBXW7 is related to the susceptibility and poor prognosis of cervical squamous carcinoma. Biomarkers 21, 379–385 10.3109/1354750X.2016.1148778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hagedorn M. et al. (2007) FBXW7/hCDC4 controls glioma cell proliferation in vitro and is a prognostic marker for survival in glioblastoma patients. Cell Div. 2, 9 10.1186/1747-1028-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koh M.S., Ittmann M., Kadmon D., Thompson T.C. and Leach F.S. (2006) CDC4 gene expression as potential biomarker for targeted therapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 78–83 10.4161/cbt.5.1.2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia W. et al. (2017) MicroRNA-32 promotes cell proliferation, migration and suppresses apoptosis in breast cancer cells by targeting FBXW7. Cancer Cell Int. 17, 14 10.1186/s12935-017-0383-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chiang C.H., Chu P.Y., Hou M.F. and Hung W.C. (2016) MiR-182 promotes proliferation and invasion and elevates the HIF-1alpha-VEGF-A axis in breast cancer cells by targeting FBXW7. Am. J. Cancer Res. 6, 1785–1798 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Akhoondi S. et al. (2010) Inactivation of FBXW7/hCDC4-beta expression by promoter hypermethylation is associated with favorable prognosis in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 12, R105 10.1186/bcr2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ibusuki M., Yamamoto Y., Shinriki S., Ando Y. and Iwase H (2011) Reduced expression of ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 mRNA is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 102, 439–445 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01801.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wei G., Wang Y., Zhang P., Lu J. and Mao J.H. (2012) Evaluating the prognostic significance of FBXW7 expression level in human breast cancer by a meta-analysis of transcriptional profiles. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 4, 299–305 10.4172/1948-5956.1000158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]