Abstract

Zoonotic filarial infections particularly dirofilariasis have been reported worldwide. The route of transmission to human beings is vector-borne through mosquitoes. Increased mosquito activity subsequent to global warming has influenced the transmission of dirofilarial infection in many geographic regions, including Asia. Dirofilariasis presents as mucocutaneous and pulmonary infections. Dirofilarial infections rarely manifest in the oral and perioral region and can pose to be a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. We report the first case of oral dirofilariasis in Goa, India.

Keywords: Dirofilaria repens, nematode, oral dirofilariasis

INTRODUCTION

Human dirofilariasis is a zoonotic infection caused by the filarioid nematode of genus Dirofilaria and is reported worldwide. In the old world (Africa, Asia, and Europe) subcutaneous infestations by Dirofilaria repens is more common as compared to the new world (Americas), where cases of pulmonary dirofilariasis by Dirofilaria immitis predominate.[1]

Among the forty species of Diroflaria, six species namely D. immitis, D. repens, Diroflaria striata, Diroflaria tenuis, Diroflaria ursi and Diroflaria spectans are known to cause diseases in humans.[2] In India, D. repens is found to be the most common pathogen causing human subcutaneous dirofilariasis resulting in a granulomatous nodule.[1]

The most significant risk factors for human infections are density of competent mosquito vectors, warm climate with extended mosquito breeding season, and an abundance of microfilaremic dogs.[1,3,4] Increasing number of cases reported in literature point toward the trend of human dirofilariasis becoming an emerging zoonosis. However, dental clinicians are usually unaware of the existence of such an infestation. We report the first case of oral dirofilariasis in Goa, India and aim to acquaint the dental health professionals with the possibility of dirofilarial infestation in sub-mucosal swellings presenting in the oral and perioral regions.

CASE REPORT

A routine excisional biopsy specimen was submitted in 10% formalin solution, to the Department of Oral Pathology for histopathological evaluation. The biopsied specimen was taken from the right buccal vestibule of a 37-year-old female patient, who had presented with a chief complaint of a swelling in the right cheek for 2 months. The patient had given a history of blunt trauma to the right side of the face 2 months back, subsequent to which she developed the swelling. Intra-oral examination had revealed the swelling to be a firm sub-mucosal nodule in the right buccal vestibule, measuring approximately 1 cm × 1 cm in dimension, nontender, and not fixed to adjacent structures with normal overlying mucosa. The clinical differential diagnosis included traumatic neuroma, herniation of buccal fat pad and benign tumors such as lipoma or fibrolipoma, neurofibroma, and pleomorphic adenoma.

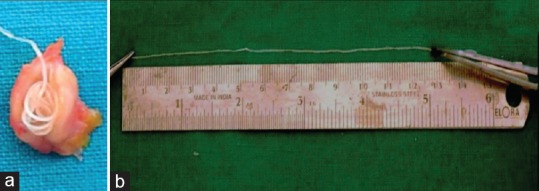

Routine blood investigation revealed all parameters within normal limits. Gross examination and dissection of the specimen revealed a cystic cavity with an opaque white, coiled, thread-like nematode [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Gross specimen: Nematode seen within cyst-like cavity (a) measuring approximately 13.3 cm in dimensions (b)

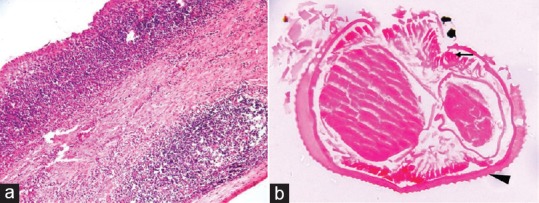

The wet mount of nematode in glycerine was examined under the light microscope [Figure 2]. The cystic specimen and part of the nematode were taken up for routine tissue processing. The hematoxylin- and eosin-stained section of the soft-tissue specimen revealed a cyst such as cavity lined by thick fibrous connective tissue capsule with dense chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, forming germinal centers. The hematoxylin- and eosin-stained section of the nematode revealed a cuticle with external ridges and micro-ruffling of the surface, well-developed polymyarian type muscle cells, and tubular digestive system along with female reproductive organs [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Wet mount (×400) of the nematode under light microscope revealed distinct, rounded longitudinal ridges (arrow) and fine transverse striations in the cuticle

Figure 3.

H- and E-stained sections: (a) cystic capsule showing well-formed germinal center (×100) and (b) Nematode (Transverse Section) (×400) showing polymyarian type muscle cells (arrow) and cuticle with external ridges and micro-ruffling (arrowhead)

Diagnostic assistance was sought from National Vector Borne Disease Control Program, Directorate of Health Services-Goa; National Centre for Disease Control-New Delhi and Centers for Disease Control-Reference Diagnostic Laboratory, United States via electronic communication of the patient data and images.

The macroscopic and microscopic findings of the nematode were confirmed to be consistent with the diagnosis of D. repens nematode.

DISCUSSION

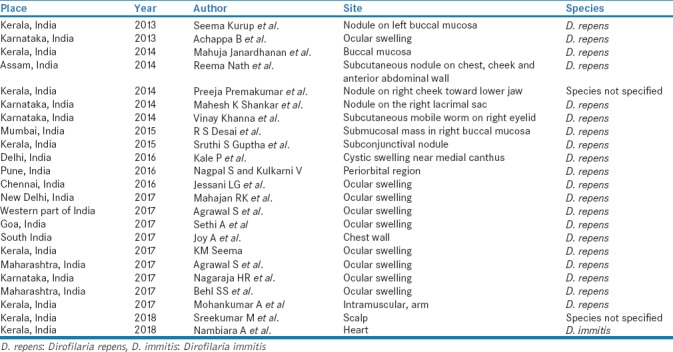

Human dirofilarial infections have been reported to be an emerging zoonosis in Africa, Asia, and Europe.[4] Increased number of dirofilarial infections in human have been reported over the past years indicating that human dirofilariasis is an emerging zoonosis in India. Kini et al., in their review reported 73 cases of human dirofilariasis in India from 1976 to 2012.[5] A thorough review of literature [Table 1], revealed an additional of twenty-three cases reported from India between the year 2013-August 2018. Mapping the disease in India, the most common site of infection in the head and neck region was the eye followed by the buccal mucosa. In an epidemiological report by Sałamatin et al., the oral cavity was found to be the second most common site for dirofilarial infestation.[6] Tilakaratne and Pitakotuwage have reported that the most commonly involved site is the buccal mucosa.[7,8]

Table 1.

Cases of human dirofilariasis reported from India between the year 2013-August 2018

D. repens was found to be the most important species responsible for human infections with maximum number of cases being reported in Kerala.[1,9]

Dogs and wild canides are the definitive hosts, humans are incidental hosts and acquire Dirofilaria when bitten by the female mosquitoes of the Culicidae family (genera Aedes, Culex, and Anopheles).[10,11] The deposition of hemolymph during a blood meal infects the host with the stage three larvae. In man, D. repens usually wanders in the subcutaneous tissues or produces a granulomatous nodule in the subcutaneous and sub-conjunctival tissues; intra-oral involvement is unusual. Pulmonary dirofilariasis is usually caused by D. immitis, while D. repens is implicated in superficial subcutaneous nodules.[3,12]

The sub-mucosal nodule in the buccal mucosa of our patient may be due to migration of the nematode from the facial subcutaneous tissue inward to the buccal mucosa. The superficial subcutaneous or sub-mucosal infections in humans are typically caused by a single nematode; therefore, surgical removal of the parasite is usually adequate to treat human infections.[13]

It is important for pathologists to be familiar with the histopathological characteristics of the nematode in routine histopathological sections. A number of macroscopic and microscopic morphological distinguishing features can help in distinguishing D. repens from D. immitis.[2,14]

The D. repens nematodes are usually smaller in size as compared to D. immitis. The female D. repens nematodes measure approximately 100–170 mm in length and 4.6–6.3 mm in diameter, whereas the female D. immitis nematode measures approximately 250–300 mm in length and 1–1.3 mm in diameter. The male D. repens nematodes measure approximately 50–70 mm in length and 3.7–4.5 mm in diameter whereas the male D. immitis nematodes measure approximately 120–200 mm in length and 0.7–0.9 mm in diameter. Microscopic examination of the nematodes can reveal characteristic differences in their cuticle. D. repens has a thick cuticle (measuring approximately 8–40 μm) whereas D. immitis has a thin cuticle (measuring approximately 9–12 μm in male and 5–25 μm in female nematodes). Light microscopic examination of D. repens shows distinct rounded longitudinal ridges and fine transverse striations in the cuticle, while the cuticle of D. immitis is relatively smooth.[15]

This case was the first case of intra-oral dirofilarial infestation in Goa. A number of different advanced DNA-based molecular techniques can be used for the species identification of the parasite. In this case, the biopsied specimen was submitted for histopathological evaluation in formalin, precluding any further molecular characterization.

Investigating further, the Institute of Veterinary Sciences Tonca, Goa, India reported an increased incidence of canine dirofilariasis in Goa. In our patient, the exact source of infection could not be determined; however, the infection was likely acquired from her region of residence, as her travel history was negative.

Human infection with D. repens has been increasing in India; many of them remain undiagnosed or unpublished. Awareness of an infection risk and oral presentation of dirofilariasis is essential for a correct diagnosis and management, especially in the light of few reported cases. Further monitoring of human dirofilariasis is necessary to establish guidelines for preventive measures, including effective chemoprophylaxis in animals.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Departments of Oral Medicine Diagnostic Radiology and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Goa Dental College and Hospital, Goa, India; Department of Microbiology, Goa Medical College and Hospital, Goa, India; Institute of Veterinary Sciences Tonca, Goa, India; National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme – New Delhi, India and Center for Disease Control and Prevention-United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nath R, Bhuyan S, Dutta H, Saikia L. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis in Assam. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:75–8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai RS, Pai N, Nehete AP, Singh JS. Oral dirofilariasis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:593–4. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.167342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon Martin F, Genchi C. Dirofilariasis and other zoonotic filariases: An emerging public health problem in developed countries. Res Rev Parasitol. 2000;60:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tappe D, Plauth M, Bauer T, Muntau B, Dießel L, Tannich E, et al. A case of autochthonous human Dirofilaria infection, Germany, March 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kini RG, Leena JB, Shetty P, Lyngdoh RH, Sumanth D, George L. Human dirofilariasis: An emerging zoonosis in India. J Parasit Dis. 2015;39:349–54. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sałamatin RV, Pavlikovska TM, Sagach OS, Nikolayenko SM, Kornyushin VV, Kharchenko VO, et al. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Ukraine, an emergent zoonosis: Epidemiological report of 1465 cases. Acta Parasitol. 2013;58:592–8. doi: 10.2478/s11686-013-0187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilakaratne WM, Pitakotuwage TN. Intra-oral Dirofilaria repens infection: Report of seven cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:502–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurup S, Veeraraghavan R, Jose R, Puthalath U. Filariasis of the buccal mucosa: A diagnostic dilemma. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:254–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popescu I, Tudose I, Racz P, Muntau B, Giurcaneanu C, Poppert S, et al. Human Dirofilaria repens infection in Romania: A case report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2012. 2012:472976. doi: 10.1155/2012/472976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guptha SS, Ranjakumar TC, Lalith S, Rahana MA, Syed A, Mohammad H. Beware of foreign body sensation” this live worm can swim through your eye! – A case series on increasing prevalence of ocular dirofilariasis in tropical India: A disease of travel to foreign lands. Int J Rec Surg Med Sci. 2015;1:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira LL, Coletta RD, Monteiro LC, Ferreira VY, Leon JE, Bonan PR, et al. Dirofilariasis involving the oral cavity: Report of the first case from South America. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:361–3. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0025-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph E, Matthai A, Abraham LK, Thomas S. Subcutaneous human dirofilariasis. J Parasit Dis. 2011;35:140–3. doi: 10.1007/s12639-011-0039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna V, Shenai S, Tilak K, Shailaja S, Malik N, Shashidhar V, et al. Subcutaneous infection with Dirofilaria repens – A case report. Hum Parasitol Dis. 2014;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed M, Singh MN, Bera AK, Bandyopadhyay S, Bhattacharya D. Molecular basis for identification of species/isolates of gastrointestinal nematode parasites. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:589–93. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: The emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:507–44. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]