Abstract

Background and Objective:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is one of the most important diseases worldwide, with a different range of prevalence in endemic areas. Anthroponotic and zoonotic CL are two epidemiological forms of CL, in Iran. Although Ilam Province in the west of Iran is one of the main endemic areas of the disease, there is no inclusive study to determine the genetic variations of parasite in these areas. The objective of this study was to determine the genetic diversity of Leishmania species in Ilam Province, using mini-circle kDNA gene.

Materials and Methods:

Direct smears were taken from skin lesions of 200 suspected cases of CL. Smears were stained, screened under light microscope. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed, using specific kinetoplast DNA primers. Data were analyzed, using the molecular bio-software.

Results:

All the samples were positive by direct examination. PCR results showed all cases were positive for Leishmania major. Although all isolated cases belong to a different county of Ilam province, all were positive for L. major with intra-species genetic diversity, divided into four clades in the dendrogram.

Interpretation and Conclusion:

This variation can affect drug resistance and controlling strategies of parasite. It is possible that different species of sand flies and rodents are the vector and reservoir of parasite, respectively; however, further studies are needed to validate this.

Keywords: Heterogeneity, Iran, Kinetoplast DNA, Leishmania major

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne disease, caused by obligate intracellular parasite belongs to the order of Kinetoplastida, transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae).[1,2,3,4] Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an important health problem in many countries of the southern and eastern Mediterranean.[2,5] In fact, the World Health Organization has announced, leishmaniasis as the sixth most significant disease in tropical and subtropical areas.[5] Among all neglected tropical diseases, leishmaniasis is the most important protozoan infection, in the Middle East and North Africa region.[6]

This disease is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of 98 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas.[7] It is a major global health problem in five continents, and it is estimated that 350 million people are at risk and currently 12 million individuals are infected, worldwide.[2,8,9,10] Annually two million new clinical cases occur globally, and incidence of CL is 0.7 to1.2 million.[4,11]

Unorganized urbanization and human migration in these regions are the two main factors affecting leishmaniasis, regarding epidemiology and morbidity.[6] Despite the existence of a universal program for vectors control and leishmaniasis treatment, the disease continues to spread.[6] In recent years, factors, such as new settlements, urbanization, agricultural development, migration, regional wars, improvement of reporting systems, and ecological changes, resulted in a significant increase in CL.[2]

Annually, more than 20 thousand cases of CL are reported from different parts of Iran, while the actual number of cases is several times more than the official reports.[5] In Iran, three species of Leishmania, such as Leishmania major, Leishmania tropica, and somewhat Leishmania infantum, have caused CL lesion.[12,13]

Thus, identification of Leishmania species is important for planning control program and treatment protocols of the disease.[14] Many polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques have been used for Leishmania diagnosis and been validated. PCR technique, using kDNA gene is the most sensitive method for the detection of Leishmania parasite, and it is superior to parasitological methods for identifying the cases, missed by either microscopic examination or culture.[15] Kinetoplast is a unique DNA containing structure in the mitochondrion of the cell, consisting of two components, maxi-circle (present in a number of 30–50 copies/parasite, with 20–40 kb in length) and mini-circle kDNA (present in a number of 10,000–20,000 copies/parasite with 1 kb in length).[16,17,18,19] Kinetoplast DNA minicircles are often the first choice for leishmaniasis diagnosis, containing three highly conserved blocks conserved sequence blocks (CSB) (CSB-1, conserved blocks of synteny-2 and CSB-3).[20] The main advantage of minicircles is high copy number and variation of kDNA mini-circles, used for the analysis of genetic polymorphism.[4,16,17,21] Therefore, it is an ideal target for the identification of Leishmania species.[22] Hence, we used kDNA-PCR to determine the genetic diversity of this protozoon, in Ilam Province.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

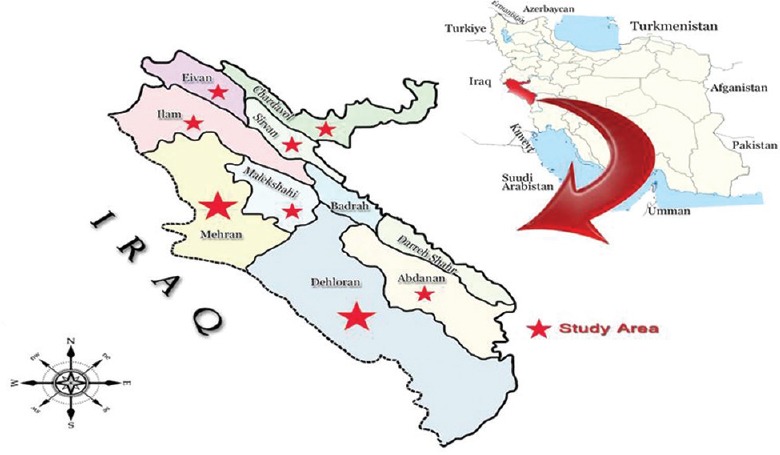

Ilam province is located in the west of Iran, in border of Iraq-Iran, covering 19,086 km2, including eight counties, in which Mehran, Dehloran, and Abdanan with a high-temperature climate, has a joint border with Iraq [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Geographical location of study area, Ilam province where samples collected to be screened for Leishmania

Sampling

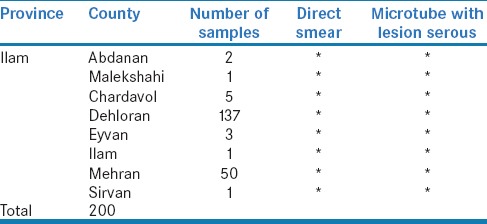

The samples [Table 1] were collected from cutaneous lesions [Figure 2], suspected with CL, and then transferred to a clinical laboratory. From all cases, medical records were collected. Direct smear was taken from each lesion of the suspected cases. Slides were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa and examined with light microscopy. Serous sample from lesion prepared in microtube, with a final volume of 250 μl phosphate-buffered saline. Samples were stored at −20°C, for DNA extraction.

Table 1.

Samples information received from different counties in the Ilam province that studied

Figure 2.

Cutaneous lesions of patient with suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis

Genomic DNA extraction

Total DNA was extracted from all samples. 100 μl of each sample was used for DNA extraction process, using the DNA extraction kit (DNG-plus™, Cinna Gene, Iran). Then the DNA extraction was performed, according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was stored at −20°C, for further analysis.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification

Extracted DNA was amplified by PCR, using specific primers for kDNA mini-circles. The primers were designed, as previously reported by Noyes et al.: forward primer: 13Z (ACTGGGGGTTGGTGTAAAATAG), homologous to conserved sequence block 3, and reverse primer: LiR (TCGCAGAACGCCCCT), complementary to conserved sequence block 1, amplifying 560, 750, and 680 bp fragments for L. major, L. tropica, and L. infantum, respectively.[23] Each 25 μl reaction mixture, contained 1x PCR,1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, 2.5 U Taq (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA, USA) and 1 μM of each primer. A total of, 35 cycles were performed, using a PCR-Thermal-Cycler (SensoQuest, Göttingen, Germany), using the following conditions: an Initial denaturation of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 60 s, 72°C for 90 s, and subsequent extension at 72°C for 10 min. Positive and negative control were used for each PCR reaction.

The PCR products were separated on 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by Molecular Imager Chemi Doc™ XRST (imaging system, Bio-Rad, USA), after staining with DNA safe. Single fragments of 560 bp, 750 bp, and 680 bp are indicative of the species L. major, L. tropica, and L. infantum, respectively.

RESULTS

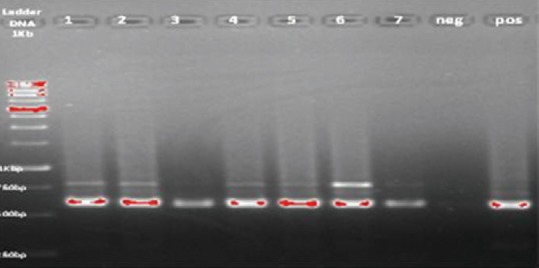

All lesions were ulcerative with different size. Isolates that caused great scars, located in the same clade in the dendrogram. According to the questionnaires, all the patients, suffering from L. major infections were from endemic areas or had a history of travel to endemic areas. Leishmania amastigote was identified, using Giemsa-stained smears, obtained from all isolated samples. Some PCR products represent a mixed infection, from two to three species of Leishmania. All the samples were examined, using PCR. Species-specific band observed in all the samples [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Detection of Leishmania parasite using kDNA gene, lanes1-7 patients samples, neg: Negative control, pos: Positive control

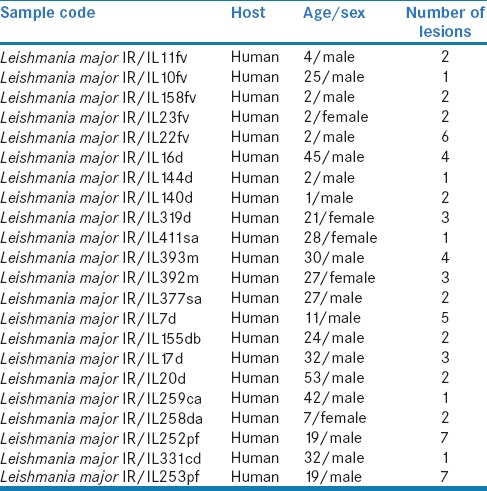

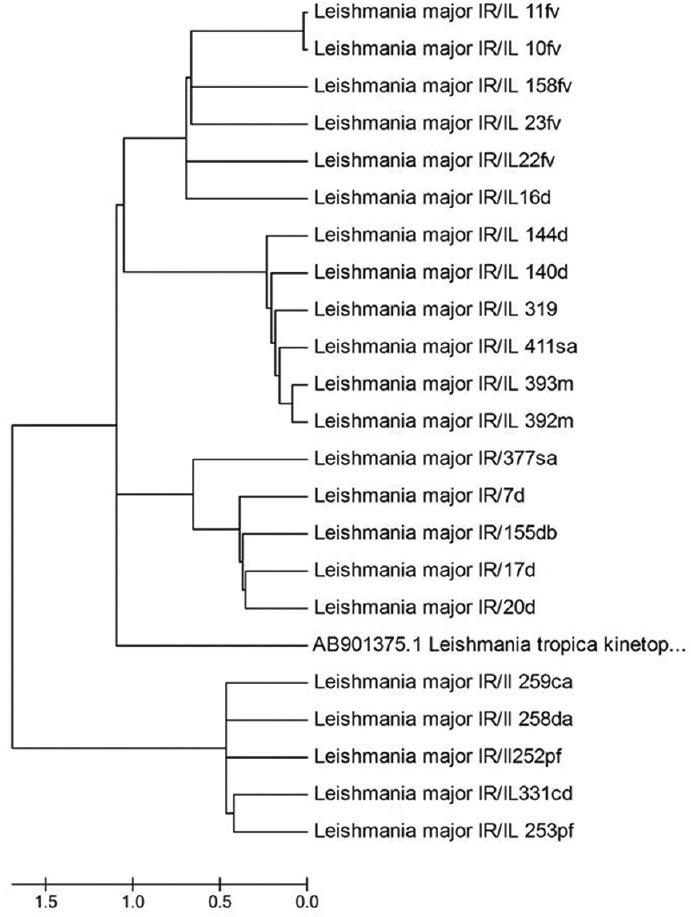

At least, 20 L. major kDNA haplotypes have been identified, by sequence alignment, in comparison with sequences, presented in GenBank. Only 20 out of 80 (25%) PCR products had sufficient amount of amplified DNA, which have been used for direct sequencing [Table 2]. Dendrogram of kDNA gene sequences of isolates, constructed by the neighbor-joining method, using Mega 6 software [Figure 4]. Sequences designated as L. major IR/IL. L. tropica (accession number AB901375), was used as the out-group. Bootstrap values (%) are indicated at the internal nodes (1000 replicates).

Table 2.

Details of patients from whom Leishmania ware isolated

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the kDNA gene sequences of Leishmania isolates constructed by the neighbor-joining method using Mega6 software (version 6). Isolates or strains names are as provided in Genbank as available. Sequences generated in this study named as Leishmania major IR/Il. Leishmania tropica (accession number AB901375.1) used as the out-group

DISCUSSION

Due to the heterogeneity among Leishmania species, and various clinical manifestation, as well as different types of lesions in humans, the diagnosis is difficult or this has led to a misdiagnosis. Different molecular techniques, such as various types of PCR, have been used, as accurate tools for definitive diagnosis of the disease. Therefore, characterization and identification of Leishmania species are necessary, because of different forms of CL, caused by different species, which may require specific control measures and treatment programs.[22]

In this study, 200 samples of suspected ulcer were used, 130 (65%) were from males, and 70 (35%) were from females. The age of the patients was in the range of 6 months to 86 years old. In addition, the diameter of the lesions was from 2 mm to 10 cm, and the number of lesions was from 1 to 13. PCR amplification of kDNA gene was used for the diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania species. All the samples were positive, using direct examination and PCR method.

In this study, we have used kDNA gene as a tool to evaluate the genetic diversity of Leishmania spp. The kDNA contains thousands of minicircles and dozens of maxicircles, concatenated in a giant network.[24] The structure of kinetoplast DNA is unique for a mitochondrial genome.[23,25,26] The 10,000 kinetoplast minicircles are distributed among 10 different sequence classes.[4,23,27,28,29] The number of mini-circles in each class is very variable, dividing into conserved and variable region.[4,23,30] The high copy number (10000–26000) of the Leishmania minicircles, makes it as a reliable target for molecular analysis of Leishmania spp.[4,24,29,31,32] The conserved region of these minicircles has been used as a diagnostic PCR target, since 1990s.[33] The kDNA-PCR seems to be the most sensitive approach for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis, suggested being implemented as the standard method for routine diagnosis, if the identification of species does not require.[34]

In this study, despite the fact that all isolates belonged to a different county in Ilam province, but all were positive for L. major. Our analysis showed an intra-species genetic diversity, and 20 isolates were divided into four clades in the dendrogram. So that, Clade 1 contains (10fv, 11 fv, 22 fv, 23 fv, and 158 fv taken from the Farrukhabad village in Dehloran county and 16d belongs to the Dehloran city), geographically closed to each other. Clade 2 contains 319 d, 140 d, and 144d taken from the city of Dehloran, 411sa from Salehabad in Mehran county, 392 m and 393 m in Mehran county, which they joined together in the dendrogram. Dehloran and Mehran are geographically close, located at the joint border of Iraq-Iran. Clade 3 contains (7 d, 17 d, and 20 d taken from Dehloran county, 155, db that is in the proximity of Dhiraj dham near Dehloran, and 377, sa in Mehran county). Clade 4 contains 5 strains, belonging to different areas of Dashtabas and Dehloran county. Rodent and sand flies as the reservoirs and a vector of the disease, respectively, can easily be transferred between Iran and Iraq, by pilgrimage travelers and border control officers, changing the disease epidemiology and genetic diversity between different isolates and spread of imported strains between Iran and Iraq. Interestingly, some isolates collected from officers in the joint border between Iran and Iraq, created a big and serious ulcer, and joined together in the same clades (Clad 1) in the dendrogram, showing that pathogenicity of the parasite related to the genetic diversity. Furthermore, some mix infections have been observed that could not be diagnosed, decisively.

Many studies reported intra-species genetic diversity among L. major, using different target genes, based on factors, such as geographic distribution of parasite, vectors, and host reservoir.[12,35,36,37] Ayari et al. showed two different clusters of L. major, based on mitochondrial cytochrome b gene.[38] Oryan et al. showed six clusters of L. major in southern Iran, based on mini-circle kDNA.[39] Nasereddin et al. showed two main clusters in central Israel and Palestine, based on kDNA.[21] Ali et al. showed two clusters (LmA and LmB) for L. major and two clusters (LtA and LtB) for L. tropica in Iraq, based on ITS gene.[40] Studies of the Leishmania genome, using different genes, showed some degrees of diversity, affecting drug resistance and the controlling strategies for the parasite. Our data indicate the dominance of L. major and presence of intra-species genetic variation in Ilam province, requiring the codification of a precise, specific, and coherent program for disease control and further investigations, in this field.

Treatment of patients with CL depends not merely on direct examination and clinical manifestations, but molecular differentiation has a more important role in this proceeding.[15,22] The result of this study provides a new understanding concerning the treatment and control proceeding, drug resistance, and vaccination against CL, for clinicians and public health authorities.

In this study, although most of the isolated samples from Dehloran, Mehran, Eyvan, Chardavol, Ilam, Abdanan, and Malekshahi districts, were mixed infection; however, the native and main etiologic agent for CL, in the studied area, was L. major, and all patients were suffering from L. major infection. Most of the positive samples in Eyvan, Chardavol, Ilam, and Malekshahi districts, due to travelers, had stayed in endemic districts of Dehloran and Mehran. It seems that Abdanan district was recently added, to the endemic districts in this province. Our data indicated a change in the affected region and transfer of diseases to new areas, that previously have never been reported.

INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSION

Having a joint border with Iraq, economic status, the presence of vector and reservoirs, weather conditions, civil war, and lack of stable government in Iraq, have imposed the risk of Leishmaniasis outbreak, in Ilam province. Our study showed L. major, as the dominant and original species of Leishmania with intra-species genetic heterogeneity, in this province. We found four clusters of L. major in dendrogram. This variation can be due to imported strains from Iraq, by tourists. Therefore, this diversity can affect strategies for prevention, control, treatment, drug resistance, and vaccination against parasites. To draft parasite genetic map in this province, further studies are needed, with emphasis on sandflies and rodents, as vector and reservoirs of the parasite, respectively.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This article is a part of Student MS thesis No1395.52 in relation to a Research Project Code No952006-96 approved by Research Commission of Ilam University of Medical Sciences. We thank all the laboratory staffs of all hospitals and health centers that help us, in Ilam province. The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the patients for their cooperation and all the individuals participating in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karimi A, Nabipour A. Molecular prevalence of Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica in humans from the endemic region of Fars, Iran. IJBPAS. 2015;4:3090–100. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khazaei S, Hafshejani AM, Saatchi M, Salehinia H, Nematollahi SH. Epidemiologocal aspects of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2015;6:429–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rafatbakhsh S, Salehzadeh A, Yousefimashouf R, Najafimosleh M, Karimitabar Z, Khedri M. Bacteria of phlebotominae sand flies collected in Western Iran. Iran J Health Safety Environ. 2015;2:313–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Auwera G, Dujardin JC. Species typing in dermal leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:265–94. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00104-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feiz-Haddad MH, Kassiri H, Kasiri N, Panahandeh A, Lotfi M. Prevalence and epidemiologic profile of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis in an endemic focus, Southwestern Iran. J Acute Dis. 2015;4:292–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafati S, Kamhawi S, Valenzuela JG, Ghanei M. Building research and development capacity for neglected tropical diseases impacting leishmaniasis in the Middle East and North Africa: A case study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardona-Arias JA, Vélez ID, López-Carvajal L. Efficacy of thermotherapy to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bañuls AL, Hide M, Prugnolle F. LeishmaniaW and the leishmaniases: A parasite genetic update and advances in taxonomy, epidemiology and pathogenicity in humans. Adv Parasitol. 2007;64:1–09. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(06)64001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira DM, Lonardoni MV, Teodoro U, Silveira TG. Comparison of different primes for PCR-based diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:204–10. doi: 10.1016/s1413-8670(11)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khademvatan S, Salmanzadeh S, Foroutan-Rad M, Saki J, Heydari-Gorji E. Spatial distribution and epidemiological features of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southwest of Iran. Alexandria J Med. 2016;53:93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Stebut E. Cutaneous Leishmania infection: Progress in pathogenesis research and experimental therapy. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirzaei A, Schweynoch C, Rouhani S, Parvizi P, Schӧnian G. Diversity of Leishmania species and of strains of Leishmania major isolated from desert rodents in different foci of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:502–12. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaeznia H, Dalimi A, Sadraei J, Pirestani P. Determination of Leishmania species causing cutaneous leishmaniasis in Mashhad by PCR-RFLP method. Arch Razi Inst. 2009;64:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Control of the Leishmaniases: Report of a Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 22–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensoussan E, Nasereddin A, Jonas F, Schnur LF, Jaffe CL. Comparison of PCR assays for diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1435–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1435-1439.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenière SF, Telleria J, Bosseno MF, Buitrago R, Bastrenta B, Cuny G, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-based identification of new world Leishmania species complexes by specific kDNA probes. Acta Trop. 1999;73:283–93. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Godoy NS, Andrino ML, de Souza RM, Gakiya E, Amato VS, Lindoso JÂ, et al. Could kDNA-PCR in peripheral blood replace the examination of bone marrow for the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis? J Parasitol Res 2016. 2016:1084353. doi: 10.1155/2016/1084353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iniesta V, Belinchón-Lorenzo S, Soto M, Fernández-Cotrina J, Muñoz-Madrid R, Monroy I, et al. Detection and chronology of parasitic kinetoplast DNA presence in hair of experimental Leishmania major infected BALB/c mice by real time PCR. Acta Trop. 2013;128:468–72. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodgers MR, Popper SJ, Wirth DF. Amplification of kinetoplast DNA as a tool in the detection and diagnosis of Leishmania. Exp Parasitol. 1990;71:267–75. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dantas-Torres F, da Silva Sales KG, Gomes da Silva L, Otranto D, Figueredo LA. Leishmania-FAST15: A rapid, sensitive and low-cost real-time PCR assay for the detection of Leishmania infantum and Leishmania braziliensis kinetoplast DNA in canine blood samples. Mol Cell Probes. 2017;31:65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasereddin A, Azmi K, Jaffe CL, Ereqat S, Amro A, Sawalhah S, et al. Kinetoplast DNA heterogeneity among Leishmania infantum strains in central Israel and palestine. Vet Parasitol. 2009;161:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdolmajid F, Ghodratollah SS, Hushang R, Mojtaba MB, Ali MM, Abdolghayoum M, et al. Identification of Leishmania species by kinetoplast DNA-polymerase chain reaction for the first time in Khaf district, Khorasan-e-Razavi province, Iran. Trop Parasitol. 2015;5:50–4. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.145587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noyes HA, Reyburn H, Bailey JW, Smith D. A nested-PCR-based schizodeme method for identifying Leishmania kinetoplast minicircle classes directly from clinical samples and its application to the study of the epidemiology of Leishmania tropica in Pakistan. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2877–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2877-2881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceccarelli M, Galluzzi L, Diotallevi A, Andreoni F, Fowler H, Petersen C, et al. The use of kDNA minicircle subclass relative abundance to differentiate between Leishmania (L.) Infantum and Leishmania (L.) amazonensis. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:239. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2181-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avila H, Goncalves AM, Nehme NS, Morel CM, Simpson L. Schizodeme analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi stocks from South and central America by analysis of PCR-amplified minicircle variable region sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;42:175–87. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90160-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barker DC. DNA diagnosis of human leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1987;3:177–84. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fazaeli A, Fouladi B, Hashemi-Shahri S, Sharifi I. Clinical features of cutaneous leishmaniasis and direct PCR-based identification of parasite species in a new focus in Southeast of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2008;37:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minodier P, Piarroux R, Gambarelli F, Joblet C, Dumon H. Rapid identification of causative species in patients with old world leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2551–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2551-2555.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues EH, Soares FC, Werkhäuser RP, de Brito ME, Fernandes O, Abath FG, et al. The compositional landscape of minicircle sequences isolated from active lesions and scars of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:228. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karamian M, Motazedian MH, Fakhar M, Pakshir K, Jowkar F, Rezanezhad H, et al. Atypical presentation of old-world cutaneous leishmaniasis, diagnosis and species identification by PCR. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:958–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degrave W, Fernandes O, Campbell D, Bozza M, Lopes U. Use of molecular probes and PCR for detection and typing of Leishmania – A mini-review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1994;89:463–9. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761994000300032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson L. Kinetoplast DNA in trypanosomid flagellates. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;99:119–79. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ceccarelli M, Galluzzi L, Migliazzo A, Magnani M. Detection and characterization of Leishmania (Leishmania) and Leishmania (Viannia) by SYBR green-based real-time PCR and high resolution melt analysis targeting kinetoplast minicircle DNA. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koltas IS, Eroglu F, Uzun S, Alabaz D. A comparative analysis of different molecular targets using PCR for diagnosis of old world leishmaniasis. Exp Parasitol. 2016;164:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahnaz T, Al-Jawabreh A, Kuhls K, Schönian G. Multilocus microsatellite typing shows three different genetic clusters of Leishmania major in Iran. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:937–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parvizi P, Ready PD. Nested PCRs and sequencing of nuclear ITS-rDNA fragments detect three Leishmania species of gerbils in sandflies from Iranian foci of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1159–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parvizi P, Moradi G, Akbari G, Farahmand M, Ready PD, Piazak N, et al. PCR detection and sequencing of parasite ITS-rDNA gene from reservoirs host of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Iran. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:1273–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1124-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayari C, Ben Othman S, Chemkhi J, Tabbabi A, Fisa R, Ben Salah A, et al. First detection of Leishmania major DNA in Sergentomyia (Sintonius) clydei (Sinton, 1928, Psychodidae: Phlebotominae), from an outbreak area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;39:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oryan A, Shirian S, Tabandeh MR, Hatam GR, Randau G, Daneshbod Y, et al. Genetic diversity of Leishmania major strains isolated from different clinical forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southern Iran based on minicircle kDNA. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;19:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali MA, Rahi AA, Khamesipour A. Species typing with PCR–RFLP from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients in Iraq. Donnish J Med Med Sci. 2015;2:26–31. [Google Scholar]