Abstract

Metastases are responsible for the majority of cancer-related deaths. While genomic heterogeneity within primary tumors is associated with relapse, heterogeneity among treatment-naïve metastases has not been comprehensively assessed. We analyzed sequencing data for 76 untreated metastases from 20 patients and inferred cancer phylogenies for breast, colorectal, endometrial, gastric, lung, melanoma, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. We found that within individual patients a large majority of driver gene mutations are common to all metastases. Further analysis revealed that the driver gene mutations that were not shared by all metastases are unlikely to have functional consequences. A mathematical model of tumor evolution and metastasis formation provides an explanation for the observed driver gene homogeneity. Thus, single biopsies capture most of the functionally important mutations in metastases and therefore provide essential information for therapeutic decision making.

The clonal evolution model of cancer proposes that cells accrue advantageous mutations and clonally expand such that these mutations are eventually present in all tumor cells (1–4). Recent studies reported mutations in putative driver genes that were only present in subpopulations of tumor cells (5, 6). The extent to which the acquisition of advantageous mutations continues after the initiation of the primary tumor (7) or during metastasis formation is unknown (8, 9). The growing list of putative driver genes and the increased sensitivity of next-generation sequencing have facilitated the discovery of subclonal driver gene mutations within a tumor (5, 10). Nevertheless, the evolutionary dynamics and the clinical importance of driver gene mutation heterogeneity in solid tumors are not fully understood.

Cells acquire a few mutations during each division due to imperfect DNA replication; hence, any population of cells is genetically heterogeneous (11). Because cancer cells continue to divide after cancer initiation, many new mutations are expected to be present in tumor subpopulations. However, to assess functional heterogeneity, advantageous mutations in putative driver genes must be distinguished from neutral replication errors in those genes. For example, within oncogenes only few recurrently mutated positions are functional and therefore many mutations—even in driver genes—may not have important functional consequences. Moreover, although metastatic disease is responsible for most cancer-related deaths, the heterogeneity of driver gene mutations has predominantly been evaluated in primary tumors. Biopsies of metastatic lesions are not readily available and typically are acquired after exposure to toxic and mutagenic chemotherapies. These treatments can induce selective bottlenecks and confound the interpretation of genetic alterations.

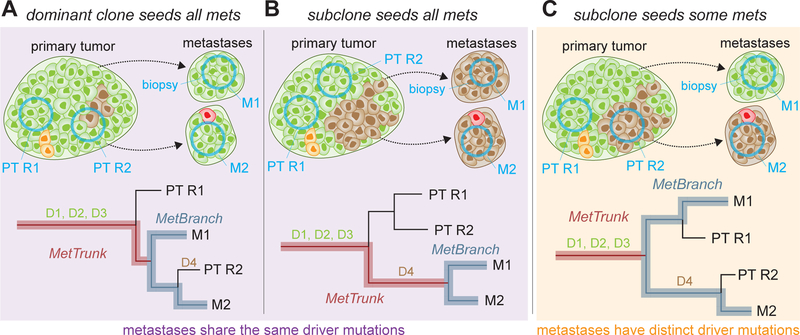

Because driver gene mutations increasingly inform clinical treatment decisions, undetected driver heterogeneity among metastases poses a barrier to the success of this precision medicine approach (12). If the founding cells of different metastases carry distinct driver gene mutations, disease progression and treatment could be fundamentally more complex than expected from a primary tumor biopsy alone. Additional driver gene mutations might be present in all or in a subset of metastases (Fig. 1). In both scenarios, more biopsies would be necessary for accurate diagnosis and optimal treatment. Here, we comprehensively analyzed the evidence for driver gene mutation heterogeneity among untreated metastases across cancer types. We also developed a mathematical model to determine the evolutionary mechanisms that give rise to inter-metastatic driver mutation heterogeneity.

Fig. 1. Three scenarios of heterogeneity of mutations in driver genes.

The original clone (green cells) contains three driver gene mutations (D1, D2, D3). Brown, yellow, and red cells acquired additional driver mutations during the growth of the primary tumor (PT) and may expand to form detectable subpopulations (brown) which can seed metastases. Top panels illustrate seeding subpopulations and biopsies (blue circles) of different regions (R1, R2) of the PT and of distinct metastases (M1, M2). Bottom panels illustrate reconstructed cancer phylogenies from those biopsies. (A) Original clone seeds all metastases. All metastases share same founding driver mutations. Subclones with additional driver mutations (D4) evolve too late to seed metastases, but might be detectable in the PT. (B) A single highly metastatic subclone evolves and gives rise to all metastases. All metastases share same founding driver mutations. (C) A new subclone with an additional driver mutation (D4) evolves and independently seeds metastases. PT regions and metastases exhibit driver mutation heterogeneity.

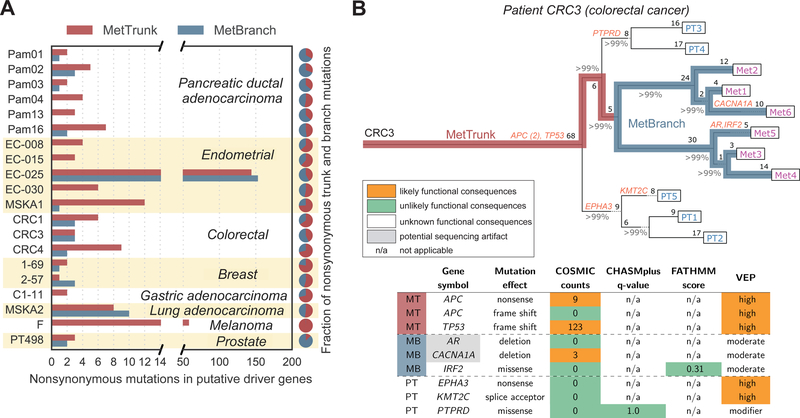

We analyzed data from 20 cancer patients for whom genome- or exome-wide sequencing was performed for at least two distinct treatment-naïve metastases (13–19). In total, we studied 115 samples including 76 untreated metastases samples from diverse tissues (mean of 3.8 and median of 3 metastases per patient) (fig. S1; table S1). We assessed somatic mutations of patients with pancreatic, endometrial, colorectal, breast, gastric, lung, melanoma, and prostate cancer (Fig. 2A). We classified nonsynonymous variants into putative driver and passengers mutations according to the TCGA consensus list of 299 putative driver genes (10). To allow for a consistent interpretation of driver gene mutation heterogeneity, we excluded two hypermutated subjects with more than 1000 nonsynonymous mutations and focused on the remaining eighteen subjects. In these subjects, we found a median of 4.5 mutated driver genes (range 2–18) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Most mutations in putative driver genes occur on the trunk of metastases.

(A) Twenty patients with 76 untreated metastases. Thirteen patients acquired mutations in putative driver genes along the MetBranch (MB) while seven did not. (B) Inferred phylogeny of a colorectal cancer exhibits inter-metastatic driver mutation heterogeneity. Nonsynonymous mutations in driver genes are denoted in orange. Percentages denote branch confidence. Integers denote number of point mutations per branch. Table shows predicted functional effects of mutations in driver genes. Heterogeneous driver mutations were predicted to have no functional effect or were likely sequencing artifacts (low coverage and low VAF across all sites). MetTrunk (MT) denotes that variant was acquired on the trunk of all metastases. Sample origin: rectum: PT1–5; liver: Met1–6.

To determine the evolutionary timing of somatic mutations, we inferred cancer phylogenies and mapped all variants onto evolutionary trees (20) (supplementary materials; fig. S2). We classified mutations into those present in all metastases (MetTrunk, hereafter referred to as trunk) and those present in a subset of metastases (MetBranch, hereafter referred to as branch) (Fig. 2B). We observed similar numbers of nonsynonymous or splice-site variants (hereafter referred to as nonsynonymous) in both categories (Fig. 2A). In contrast, trunks exhibited a 2-fold enrichment of the ratio of driver gene mutations to nonsynonymous mutations compared to branches (9.1% vs. 4.0%, two-sided paired t-test P = 0.004; Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, we observed mutations in driver genes that were heterogeneous among metastases for 12 of 18 subjects.

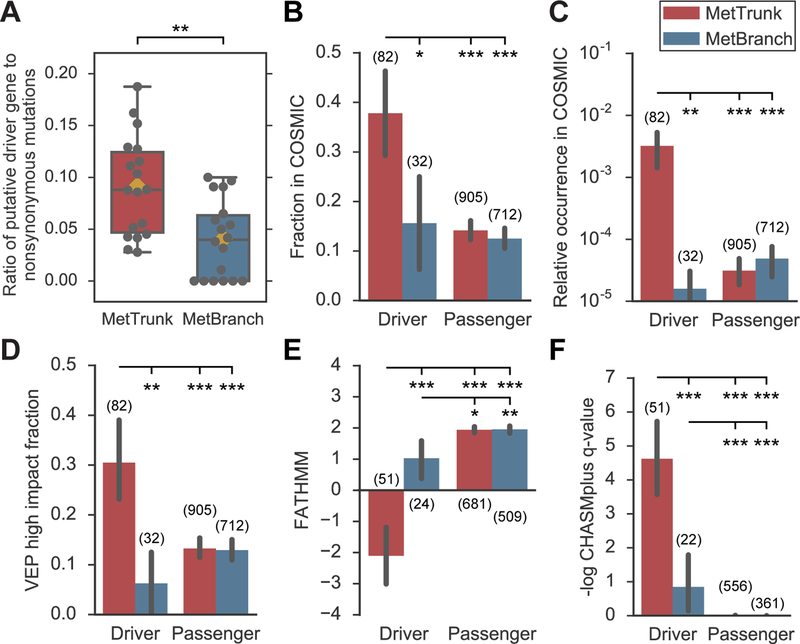

Fig. 3. Predicted functional mutations in putative driver genes are strongly enriched along metastases trunks.

(A) Ratio of driver gene mutations to nonsynonymous mutations is enriched by 42-fold along trunks compared to branches. Orange diamond denotes mean, black bar denotes median (two-sided paired t-test P = 0.004). (B) Fraction of nonsynonymous variants in driver genes along MetTrunk in COSMIC was 38% compared to 16% along MetBranch (two-sided Fisher’s exact test P = 0.025). (C) Relative occurrence of variants in driver genes along MetTrunk in individual COSMIC samples was 0.32% compared to 0.0016% along MetBranch (two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test P = 0.008). (D) VEP inferred that 30% and 6% of driver gene mutations were of high impact along MetTrunk and MetBranch, respectively (two-sided Fisher’s exact test P = 0.006). (E-F) FATHMM (value below −0.75 indicates likely driver mutation) and CHASMplus predicted increased functional consequences for variants in driver genes in MetTrunk. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used. Thick black bars denote 90% confidence interval. No other statistically significant differences were observed. Numbers in brackets denote number of variants in each group. * indicates P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

To investigate whether heterogeneous mutations in putative driver genes were likely to be functional, we employed a variety of approaches. We found that a large proportion of nonsynonymous variants in driver genes along trunks were previously detected at least once in other cancers (COSMIC, Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer; 37.8%, 31/82) whereas a much smaller proportion along branches was present in COSMIC (15.6%, 5/32; two-sided Fisher’s exact test P = 0.025; Fig. 3B). The fraction of driver gene mutations in branches in COSMIC was in fact similar to that of passenger gene mutations in either trunks or branches (14.1%, 128/905 and 12.5%, 89/712). Because mutations that are true drivers are often recurrent, we investigated how frequently identical nonsynonymous variants were found in COSMIC. While variants in driver genes along trunks on average occurred in 0.32% COSMIC samples (occurrence mean of 82.0 in 25,516 COSMIC samples), driver gene mutations acquired along branches occurred more than 100-fold less frequently (0.0016%; Fig. 3C; two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test P = 0.008).

We then utilized several methods to predict the functional impact of 1,755 nonsynonymous variants along trunks and branches. We found that driver gene mutations acquired along trunks were more likely to have predicted functional consequences (Fig. 3, D-F; fig. S3). Variants with the most likely protein-changing effects (mutation consequences with high impact, e.g., frameshift or nonsense mutations) were frequently observed in driver genes along trunks but rarely observed along branches (30.5% vs 6.3%; two-sided Fisher’s exact test P = 0.006; Fig. 3D). The frequency of high impact variants in driver genes along branches was no higher than that in passenger genes. FATHMM (21) predicted significantly stronger functional effects for driver gene mutations along trunks than along branches (mean scores of −2.1 vs. 1.0; scores below −0.75 indicate likely driver mutation; two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test P < 0.001; Fig. 3E). Similarly, CHASMplus (22) predicted significantly higher gene-weighted scores for driver gene mutations along trunks than along branches (mean scores 0.47 vs. 0.16; higher values indicate likely functional effects; two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test P < 0.001; Fig. 3F).

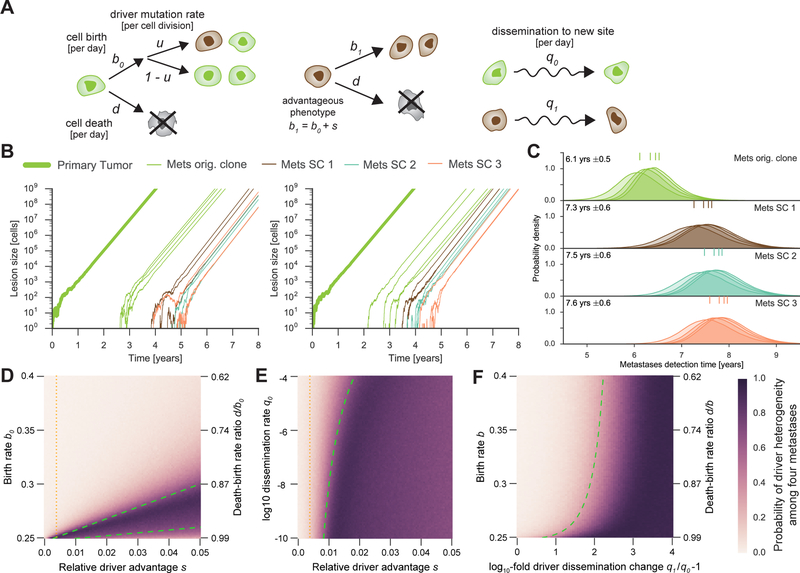

To identify the evolutionary determinants of inter-metastatic heterogeneity, we developed a mathematical framework to assess how rates of growth, mutation, and dissemination give rise to driver gene mutation heterogeneity (23, 24) (supplementary materials). The original clone in the primary tumor grows with a rate of r0 = b0 – d0 per day (birth rate , death rate for each clone ) and disseminates cells to distant sites with rate per day (Fig. 4A). When a cell divides, a daughter cell can acquire an additional driver mutation with probability . This model produces inter-metastatic heterogeneity if not all detectable metastases were seeded from the same subclone in the primary tumor.

Fig. 4. Mathematical analysis provides an explanation for inter-metastatic driver gene mutation homogeneity or heterogeneity.

(A) Primary tumor expands stochastically from a single advanced cancer cell and seeds metastases. Cells of original clone (green) divide at rate b0 and die at rate d per day. Additional driver mutations increase the birth rate to b1 = b0(1+s), where s denotes the relative driver advantage (b1 ≥ b0, q = q1; B-E), or increase the dissemination rate (q1 ≥ q0, b1 = b0; F). (B) Representative model realizations for typical parameter values. Growth rate r0 = 1.24% per day, s = 0.4%, dissemination rate q0 = 10−7 per cell per day. (C) Distribution of metastases detection times for parameter values in B. Numbers denote mean ± standard deviation. Colored marks show mean detection times of first, second, third, and fourth metastases seeded by the corresponding subclone (SC). (D-F) Probability of distinct driver mutations among four metastases. Green dashed lines depict bounds separating parameter regions of likely inter-metastatic driver homogeneity from heterogeneity. Orange dotted lines denote s = 0.4%. (D) Fixed q0 = 10−7. (E) Fixed death-birth rate ratio d/b0 = 0.95. (F) Fixed q0 = 10−7. Other parameter values: d = 0.2475, driver mutation rate u = 3.4 10−5 per cell division.

Following previously measured growth and selection parameters, we assume a growth rate of r = 1.24% per day and a relative growth advantage of a driver gene mutation of s=0.4%(s = bi/b0 - 1) (25, 26). To mimic the composition of our cohort, we consider the first four metastases that reach a detectable size of cells (~1 cm3). We find that the probability of inter-metastatic driver heterogeneity is 10.5% (Fig. 4; d = 0.2475, q = 10−7). The original founding clone of the primary tumor most likely seeds all detectable metastases (green cells; Fig. 1A). The increased growth rate conferred by a new driver mutation is insufficient to compensate for the time spent waiting for the driver mutation to occur (figs. S4-S5).

The model reveals that the probability of observing inter-metastatic driver heterogeneity increases when the primary tumor grows very slowly before metastases are seeded, the average growth advantage of additional driver mutations is very large, and the driver gene mutation rate is high (fig. S6C). In contrast, a high dissemination rate produces less inter-metastatic heterogeneity because metastases are established before driver subclones greatly expand (Fig. 4E, fig. S7C). For very high driver growth advantages but slowly growing cancers, another scenario is possible: all metastases are seeded from the same highly advantageous subclone (Fig. 1B). Finally, if driver mutations instead increase the dissemination rate, an almost ten-fold increase is required to produce inter-metastatic driver heterogeneity (Fig. 4F; fig. S8).

In real patients, we expect less inter-metastatic heterogeneity for several reasons. First, driver gene mutations may not confer the same advantage in the microenvironment of the primary tumor and of a distant site, reducing the probability of heterogeneity (fig. S9). Second, primary tumor growth may slow down due to space or nutrient constraints or surgical removal, also reducing the expected inter-metastatic heterogeneity (fig. S10). Third, advanced cancer cells have already acquired multiple driver gene mutations in various pathways, possibly reducing the number of additionally available driver gene mutations that confer a significant selective advantage (fig. S6B).

Overall, we observed a depletion of heterogeneous mutations in putative driver genes among metastases (Fig. 3). Moreover, the majority of those that were observed had only weak or no predicted functional effects. These results are compatible with multiple recent studies on neutrally evolving cancers after transformation (7, 27, 28). However, the mathematical framework demonstrates that a lack of inter-metastatic driver heterogeneity does not imply neutral evolution but can also be explained by various other factors, including primary tumor growth dynamics (Fig. 4). Furthermore, growth rates may saturate and fitness gains of additional driver gene mutations become smaller because available resources (nutrients, oxygen, etc.) are already almost optimally utilized; a phenomenon that is observed in bacterial evolution (29).

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, we exclusively focused on single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions because their functionality can be predicted by multiple methods and their heterogeneity has immediate clinical consequences for therapy selection (12). We did not assess recurrent noncoding, copy-number, or epigenetic alterations since functional prediction methods for them are not yet available. Second, we cannot exclude the possibility that mutations in yet undiscovered driver genes of metastases are heterogeneous. Third, we could not evaluate micro-metastases that are not visible clinically.

Because therapy selection and treatment success of previously untreated patients increasingly depends on the identification of genetic alterations, it will be critical to extend this analysis to larger cohorts and more cancer types to investigate whether minimal driver gene mutation heterogeneity is a general phenomenon of advanced disease. This pan-cancer analysis of untreated metastases suggests that a single biopsy accurately represents the driver gene mutations of a patient’s metastases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants K99CA229991 (J.G.R.), CA179991 (C.A.I.-D.), F31CA180682 (A.P.M.-M.), T32 CA160001-06 (A.P.M.-M.), F31CA200266 (C.J.T.), U24CA204817 (R.K.), CA43460 (B.V.), as well as by the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research, The Sol Goldman Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, The Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, an Erwin Schrödinger fellowship (J.G.R.; Austrian Science Fund FWF J-3996), a Landry Cancer Biology fellowship (J.M.G.), and the Office of Naval Research grant N00014-16-1-2914.

Footnotes

Competing interests: K.W.K. and B.V. are founders of Personal Genome Diagnostics. B.V. and K.W.K. are on the Scientific Advisory Board of Sysmex-Inostics. B.V. is also on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Exelixis GP. These companies and others have licensed technologies from Johns Hopkins, and K.W.K. and B.V. receive equity or royalties from these licenses. The terms of these arrangements are being managed by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Data and materials availability: Accession numbers for the raw sequencing data are available in the original publications (13–18). Data of Brown et al., Hong et al., and Makohon-Moore et al. as well as of subjects MSKA1 and MSKA2 are deposited at the European Genome-Phenome Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega) and are available under accession numbers EGAS00001000760, EGAS00001000942, EGAS00001002186, and EGAS00001002777, respectively. Data of Gibson et al. and Sanborn et al. are deposited to the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession codes phs001127.v1.p1 and phs000941.v1.p1, respectively. Data of Kim et al. are deposited to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at the NCBI under the project ID of PRJNA271316.

References and Notes

- 1.Nowell PC, Science 194, 23–28 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B, Cell 61, 759–767 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, Kern SE, Clin. Cancer Res 6, 2969–2972 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greaves M, Maley CC, Nature 481, 306–313 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamal-Hanjani M et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 376, 2109–2121 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlinger M et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 366, 883–892 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sottoriva A et al. , Nat. Genet 47, 209–216 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turajlic S, Swanton C, Science 352, 169–175 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massagué J, Obenauf AC, Nature 529, 298–306 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey MH et al. , Cell 173, 371–385.e18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blokzijl F et al. , Nature 538, 260–264 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelstein B et al. , Science 339, 1546–1558 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanborn JZ et al. , Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 10995–11000 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong MKH et al. , Nat Commun 6, 6605 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim T-M et al. , Clin. Cancer Res 21, 4461–4472 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson WJ et al. , Nat Genet 48, 848–855 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makohon-Moore AP et al. , Nat. Genet 49, 358–366 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown D et al. , Nat. Commun 8, 14944 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pectasides E et al. , Cancer Discov 8, 37–48 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiter JG et al. , Nat. Commun 8, 14114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shihab HA, Gough J, Cooper DN, Day INM, Gaunt TR, Bioinformatics 29, 1504–1510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokheim C, Karchin R, bioRxiv, 313296 (2018).

- 23.Haeno H et al. , Cell 148, 362–375 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durrett R, Branching process models of cancer (Springer, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bozic I et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 107, 18545–18550 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furukawa H, Iwata R, Moriyama N, Pancreas 22, 366–369 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bozic I, Gerold JM, Nowak MA, PLoS Comput. Biol 12, e1004731 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams MJ et al. , Nat. Genet 50, 895–903 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Good BH, McDonald MJ, Barrick JE, Lenski RE, Desai MM, Nature 551, 45–50 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.