Abstract

The chemokine receptor CXCR3 plays a central role in inflammation by mediating effector/memory T cell migration in various diseases; however, drugs targeting CXCR3 and other chemokine receptors are largely ineffective in treating inflammation. Chemokines, the endogenous peptide ligands of chemokine receptors, can exhibit so-called biased agonism by selectively activating either G protein–mediated or β-arrestin–mediated signaling after receptor binding. Biased agonists might be used as more targeted therapeutics to differentially regulate physiological responses, such as immune cell migration. To test whether CXCR3-mediated physiological responses could be segregated by G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling, we identified and characterized small-molecule, biased agonists of the receptor. In a mouse model of T cell–mediated allergic contact hypersensitivity (CHS), topical application of a β-arrestin–biased, but not a G protein–biased, agonist potentiated inflammation. T cell recruitment was increased by the β-arrestin–biased agonist, and biopsies of patients with allergic CHS demonstrated coexpression of CXCR3 and β-arrestin in T cells. In mouse and human T cells, the β-arrestin–biased agonist was the most efficient at stimulating chemotaxis. Analysis of phosphorylated proteins in human lymphocytes showed that β-arrestin–biased signaling activated the kinase Akt, which promoted T cell migration. This study demonstrates that biased agonists of CXCR3 produce distinct physiological effects, suggesting discrete roles for different endogenous CXCR3 ligands and providing evidence that biased signaling can affect the clinical utility of drugs targeting CXCR3 and other chemokine receptors.

INTRODUCTION

The chemokine receptor CXCR3 is a heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G protein)–coupled receptor (GPCR) that is expressed primarily on activated effector/memory T cells and plays an important role in atherosclerosis, cancer, and inflammatory disease. Activation of CXCR3 by chemokines causes the migration of activated T cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Increased tissue concentrations of activated T cells initiate inflammatory responses, and the ability to modulate T cell chemotaxis would likely be therapeutically useful in many disease processes. Despite the importance of the more than 20 chemokine receptors in various disease states, there are currently only three FDA-approved drugs that target chemokine receptor family members (1–3). This is somewhat surprising, because GPCRs constitute the plurality of FDA-approved medications, with >30% of therapeutics targeting this class of receptors (4).The difficulty in successfully targeting chemokine receptors was originally thought to be due to redundancy across the multiple chemokine ligands and chemokine receptors that bind to one another (5). However, this presumed redundancy appears to be more granular than was initially appreciated. Similar to most other chemokine receptors, CXCR3 signals through both Gαi family G proteins and β-arrestins. GPCR signaling deviates at critical junctions, including G protein and β-arrestins, which signal through distinct intracellular pathways. For example, β-arrestins promote interactions with kinases independently from their interactions with G proteins to induce downstream signaling (6).

It is now appreciated that many chemokines that bind to the same chemokine receptor can selectively activate such distinct signaling pathways downstream of the receptor (7–9). This phenomenon is referred to as biased agonism (10, 11). Biased ligands at other GPCRs, such as the μ opioid receptor (MOR) (12, 13), the kappa opioid receptor (KOR) (14), and the type 1 angiotensin II receptor (AT1R) (15), have shown promise in improving efficacy while reducing side effects through differential activation of G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling pathways (16). Animal and human studies suggest that G protein–mediated signaling by the MOR primarily mediates analgesic efficacy, whereas β-arrestin–mediated signaling causes many adverse effects, such as respiratory depression, constipation, tolerance, and dependence (12, 13). Furthermore, relative degrees of G protein and β-arrestin bias can predict safer μ-opioid analgesics (17). At the AT1R, biased and balanced AT1R agonists have distinct physiologic responses: Gαq-dependent signaling mediates vasoconstriction and cardiac hypertrophy, whereas β-arrestin–mediated signaling activates anti-apoptotic signals and promotes calcium sensitization (15). At chemokine receptors, both pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G protein signaling and β-arrestin–mediated signaling contribute to chemotaxis (18–23). However, chemokines with distinct G protein– and β-arrestin–biased signaling properties often induce chemotaxis to similar degrees (9). The relative contribution of β-arrestin–mediated or G protein–mediated signaling to chemotaxis and inflammation is unclear, and it is experimentally challenging to discern the physiological relevance of biased signaling with peptide agonists in many assays because of the high molecular weight and short half-life of chemokines relative to those of small molecules. Indeed, it is unknown if endogenous or synthetic chemokine receptor ligands that preferentially target G protein or β-arrestin pathways would result in different physiological outcomes in models of disease and inflammation. If such differences in selective pathway activation result in distinct physiological outcomes, then biased agonism could be used to develop new insights into chemokine biology that could be harnessed to increase the therapeutic utility of drugs targeting chemokine receptors while reducing on-target side effects.

Given its prominent role in effector T cell function, we focused on biased signaling at CXCR3-A, the dominantly expressed CXCR3 isoform on T cells in humans and mice. CXCR3 signaling is implicated in various disease processes, including cancer (24), atherosclerosis (25), vitiligo (26, 27), and allergic contact dermatitis (28). The chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, the endogenous ligands of CXCR3, stimulate the chemotaxis of CXCR3-expressing T cells (29). These chemokines are secreted in response to interferon-γ (IFN-γ) by various cell types, including monocytes, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. We previously demonstrated that the three ligands of CXCR3 act as biased agonists, displaying different efficacies at signaling through G proteins and β-arrestins and stimulating receptor internalization (30, 31), suggesting that biased agonists targeting CXCR3 may have distinct physiological effects. Given the importance of CXCR3 signaling in disease, we tested whether small-molecule, biased agonists of CXCR3 could elicit biochemically and physiologically distinct effects in mice and humans.

RESULTS

Screening enabled identification of biased agonists of CXCR3 with distinct signaling profiles

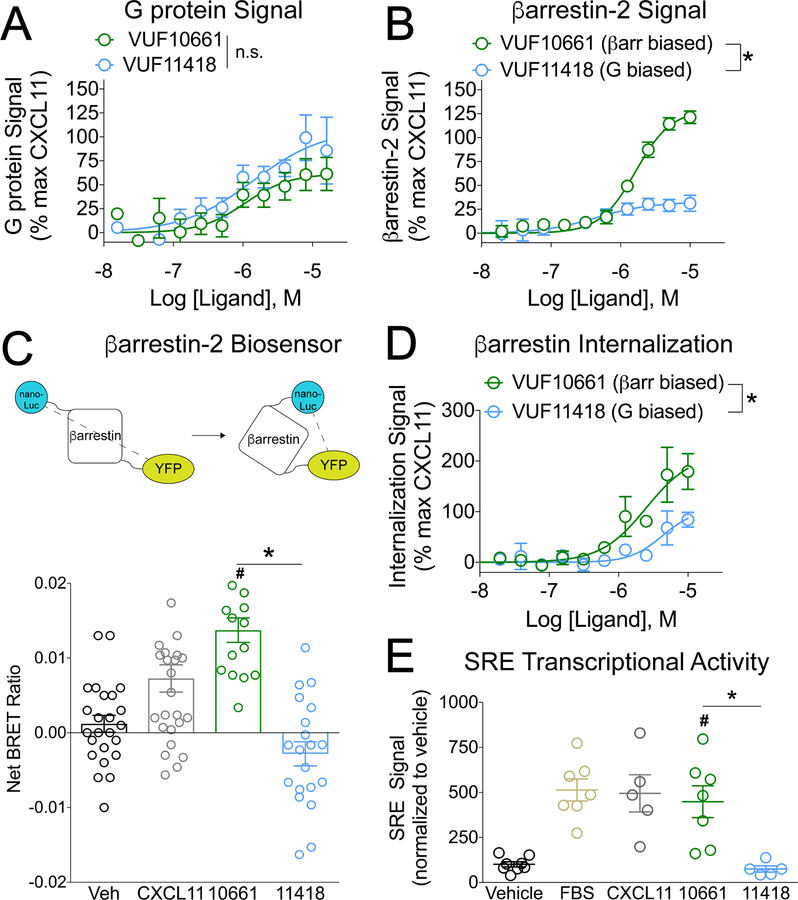

To explore the physiological relevance of biased signaling at CXCR3, we screened a panel of publicly available small-molecule CXCR3 ligands and identified two agonists with biased signaling properties: VUF10661 (32) and VUF11418 (Fig 1, A and B). These two small molecules were previously shown to have similar affinities for CXCR3 (33) (table S1). We first confirmed previous reports that both compounds signal through Gαi G proteins (Fig. 1A) (34, 35), displaying similar potencies. Because the G protein–dependent signal did not saturate at high concentrations of agonist, differences in the efficacies of both compounds to activate Gαi signaling could not be completely assessed. However, VUF10661 increased β−arrestin2 recruitment to CXCR3 compared to VUF11418 (Fig. 1B). These small-molecule CXCR3 agonists also displayed differential abilities to recruit β-arrestin1, recruit GPCR kinases (GRKs), and stimulate CXCR3 internalization (fig. S1, A to G), consistent with their biased signaling properties.

Fig 1. VUF10661 and VUF11418 are biased agonists of CXCR3.

(A) Transfected HEK 293T “ΔG six” cells expressing CXCR3 and the interrogated Gα subunit were analyzed for Gαi activation by the TGF-α shedding assay as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were treated for 1 hour with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of the G protein–biased CXCR3 agonist VUF11418 or the β-arrestin–biased CXCR3 agonist VUF10661. The extent of G protein signal is expressed as a percentage of that induced by the CXCR3 agonist CXCL11. Data are means ± SEM of eight or nine experiments. (B) Transfected HEK 293T cells expressing CXCR3-Rluc and β-arrestin2-YFP were analyzed for β-arrestin2 recruitment by BRET as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were treated for 5 min with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of VUF11418 or VUF10661. The extent of β-arrestin2 recruitment is expressed as a percentage of that induced by the CXCR3 agonist CXCL11, which was used as a control. Data are means ± SEM of four experiments. (C) Top: Schematic of the detection of a conformational change in β-arrestin by measuring BRET between a nanoLuc donor and a YFP acceptor. Bottom: Transfected HEK 293T cells expressing CXCR3 and the β-arrestin biosensor were analyzed by BRET to detect changes in the conformation of β-arrestin. The cells were treated for five minutes with vehicle, 1 μM VUF11418, 1 μM VUF10661, or 250 nM CXCL11 as a positive control and the net BRET ratio was calculated by subtracting the vehicle signal from the drug signal. Data are from 15 to 26 wells from four independent experiments. (D) U2OS cells stably expressing β-arrestin2–dependent internalization assay components (enzyme fragments tagged to β-arrestin2 and endosomes) and transiently expressing CXCR3 were analyzed for CXCR3 internalization as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were treated for 90 minutes with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of VUF11418 or VUF10661. As a control, the cells were treated with CXCL11 (1 μM). The percentage of CXCR3 internalization was calculated relative to that induced by CXCL11. Data are means ± SEM of three to five experiments. (E) Transfected HEK 293T cells expressing CXCR3 and a serum response element (SRE) reporter were analyzed by luminescence to measure changes SRE transcriptional activation. The cells were treated for 5 hours with vehicle, 10 μM VUF11418, 10 μM VUF10661, 10% FBS, or 1 μM CXCL11. The SRE signal was normalized to that of the vehicle control. Data are means ± SEM of five to eight experiments. For (A), (B), and (E), data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA; *P < 0.05 when comparing VUF10661 to VUF11418. For (C) and (F), data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05 when comparing VUF10661 to VUF11418; #P < 0.05 when compared to vehicle.

Because bias is a relative measurement, an appropriate reference must be used. Here, we used the endogenous agonist CXCL11 as a reference, which is a full agonist of CXCR3 for both G protein–mediated and β-arrestin–mediated pathways (30, 36). As expected, CXCL11 displayed increased potency for CXCR3 relative to the small-molecule agonists (fig. S1, H and I). Because it exhibited increased efficacy in β−arrestin recruitment but a similar degree of efficacy in G protein activation, VUF10661 was considered to be a β-arrestin–biased agonist relative to VUF11418 and CXCL11. Similarly, the preserved G protein activation property of VUF11418 together with its reduced ability to induce β-arrestin recruitment demonstrated that it is relatively G protein–biased compared to VUF10661 and CXCL11 (Fig 1, A and B, fig S1, H and I). Consistent with its ability to stimulate increased β−arrestin recruitment, VUF10661 also induced a distinct β−arrestin2 conformation, as assessed with an intramolecular biosensor (Fig. 1C), increased the β-arrestin–dependent internalization of CXCR3 (Fig. 1D), and promoted serum response element response factor–mediated transcription [which was previously correlated with increased β−arrestin signaling (30)] relative to VUF11418 (Fig. 1E).

A β-arrestin–biased agonist of CXCR3 potentiates T cell–mediated inflammation and chemotaxis

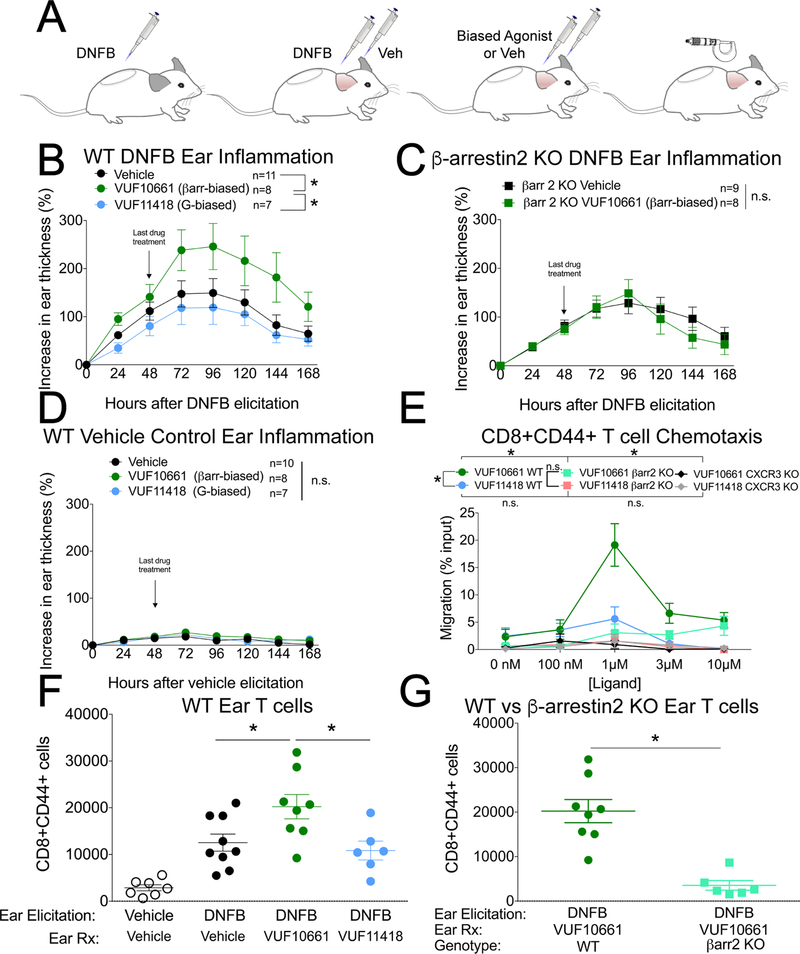

After confirming that ligand bias was conserved at the murine CXCR3 receptor, which has 86% sequence homology to human CXCR3 (fig. S2, A to D), we next studied how these small molecules affected a mouse model of allergic contact hypersensitivity (CHS), an inflammatory condition that is dependent on effector memory T cells (Fig. 2A). The CHS delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction enables an assessment of T cell–mediated inflammation and the recruitment of effector T cells to the sensitizer dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB). Topical application of the β-arrestin–biased agonist, but not the G protein–biased agonist, potentiated the inflammatory response (Fig. 2B). The potentiation induced by VUF10661 was not observed in either β-arrestin2 knockout mice (Fig. 2C) or CXCR3 knockout mice (fig. S3), consistent with the effects of VUF10661 requiring both CXCR3 and β-arrestin2, the predominant arrestin isoform in T cells (23). Furthermore, the small molecules did not cause inflammation in the absence of DNFB-induced T cell allergy and therefore did not act as irritants or haptens (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. A β-arrestin–biased, but not G protein–biased, CXCR3 agonist increases inflammation and the chemotaxis of effector/memory T cells.

(A) Experimental design of the DNFB contact hypersensitivity model of inflammation. DNFB sensitization was induced with 0.5% DNFB and contact allergy was elicited 5 days later with 0.3% DNFB. (B) Ear thickness after topical application of vehicle, the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 (50 μM), or the G protein-biased agonist VUF11418 (50 μM) on the ear of wild-type mice after DNFB elicitation. Data are means ± SEM of 7 to 11 mice per treatment group. (C) Ear thickness after topical application of the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 or vehicle on the ear of β-arrestin2 KO mice. Data are means ± SEM of 8 or 9 mice per treatment group. (D) As a negative control, in the absence of DNFB treatment, VUF10661 or VUF11418 was applied to the ears. Data are means ± SEM of 7 to 10 mice per treatment group. (E) Measurement of the chemotaxis of CD8+CD44+ T cells isolated from the indicated mice toward the indicated concentrations of the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 or the G protein–biased agonist VUF11418. VUF11418 (1 μM) did not cause statistically significant chemotaxis compared to the 0 nM treatment (P < 0.05 by two-tailed t-test). Data are means ± SEM of 3 or 4 mice per treatment group. (F) Skin infiltration by effector T cells in either vehicle or DNFB allergen–elicited WT mouse ears induced by topical application of vehicle, the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 (50 μM), or the G protein-biased agonist VUF11418 (50 μM). Data are means ± SEM of 6 to 9 mice per treatment group. (G) Skin infiltration by effector T cells in DNFB allergen–elicited β-arrestin2 KO mouse ears induced by topical application of VUF10661 (50 μM), or VUF11418 (50 μM). Data are means ± SEM of 6 to 8 mice per treatment group. For (B), *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA analysis. For (E), *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA analysis, showing statistically significant effects of drug for WT VUF10661 vs. WT VUF11418 (Tukey post hoc analysis for 1 μM; also, P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons); of genotype for WT VUF10661 vs βarr2 KO VUF10661; and of genotype for WT VUF10661 vs CXCR3 KO VUF10661.

Given the established role of CXCR3 in T cell chemotaxis (2) and the increased abundance of CXCR3 on CD8+ T cells relative to that on CD4+ T cells in allergic contact dermatitis (37), we hypothesized that the increased inflammation induced by the β-arrestin–biased agonist was due to increased effector memory CD8+ T cell chemotaxis compared to that induced by the G protein–biased agonist. Supporting this, we found that the β-arrestin–biased agonist induced more chemotaxis of effector memory T cells from wild-type mice in a transwell migration assay than did the G protein–biased agonist (Fig. 2E). This difference in migration was not observed for activated CD8+ T cells from β-arrestin2 knockout mice (Fig. 2E) and was reduced in activated CD4+ T cells (fig. S4A). Consistent with a role for β-arrestin mediating chemotaxis stimulated by other chemokine receptors (7, 38, 39), migration of effector memory T cells to the endogenous murine chemokine CXCL10 was also markedly attenuated in β-arrestin2 KO mice (fig. S4, B to E). T cells from CXCR3 KO mice failed to migrate to either the β-arrestin–biased agonist or the G protein–biased agonist (Fig. 2E).

With the relative differences in biased agonist–induced chemotaxis, we then investigated whether topical application of the biased agonists caused an increase in the number of effector memory T cells in the skin. The β-arrestin–biased agonist increased the number of effector memory cytotoxic T cells in the ear relative to the numbers induced by either vehicle or the G protein–biased agonist after treatment of WT mice with DNFB (Fig. 2F). Treatment with the β-arrestin–biased agonist VUF10661 also increased the number of effector memory T helper cells in the ear relative to the number of cells induced by treatment with the G protein–biased agonist (fig. S5, A and B). The ears of β-arrestin2 KO mice accumulated fewer effector memory T cells than did those of WT mice in response to VUF10661 (Fig. 2G and fig. S5C). No difference in the number of CD4+ regulatory T cells was observed (fig. S5, D and E). Together, these findings are consistent with the β-arrestin–biased agonist increasing skin inflammation by promoting the chemotaxis and recruitment of effector memory T cells.

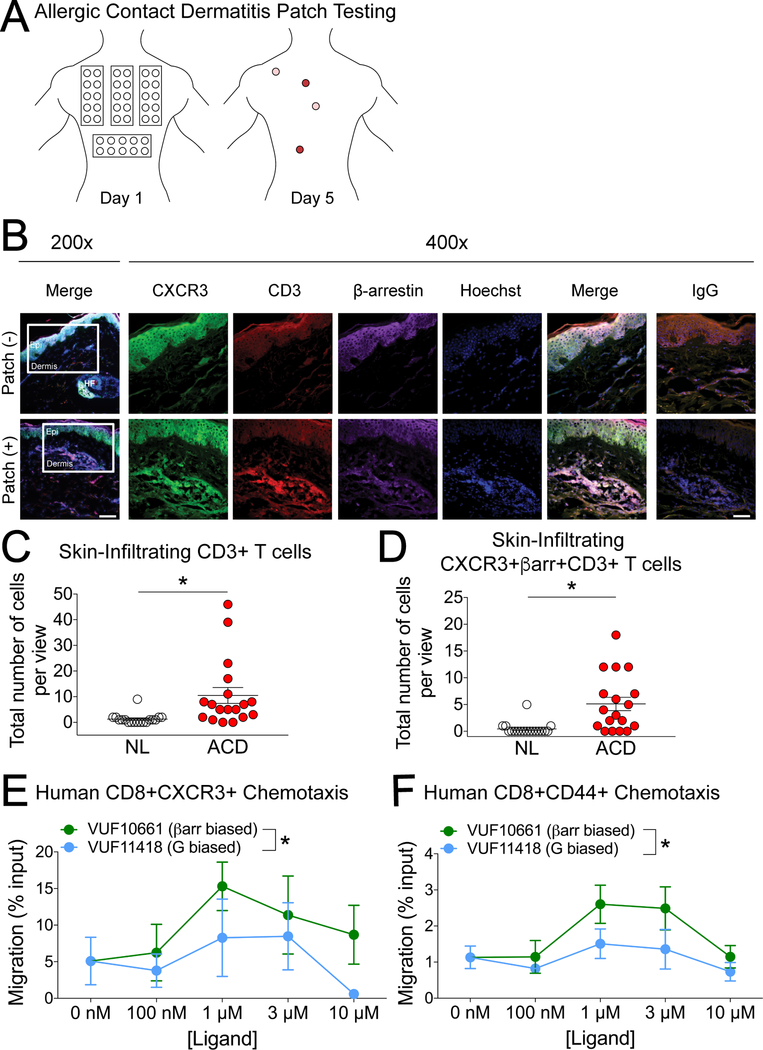

Patients with CSH coexpress CXCR3 and β−arrestin in T cells in the skin

A major confounder in studies of chemokine biology is differences in expression patterns and function between species (40). To correlate CXCR3 signaling with CSH in human patients, we sampled skin from patch-tested patients (Fig. 3A). Skin patch-testing involves the placement of contact allergens directly on the skin. Positive patch tests reactions include erythematic induration, with severe reactions causing ulceration. Patch-testing is the gold standard for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and the role of T cells in the pathophysiology of allergic CSH that underlies this disease is well-established (41). Ninety-six to 120 hours after allergen application, the patch test was read, and biopsies of positive and negative sites were collected and stained for the T cell marker CD3, CXCR3, and β-arrestin (Fig. 3B). More T cells and more T cells coexpressing CXCR3 and β-arrestin were observed in ACD biopsies than in non-lesional (negative) biopsies at the epidermal-dermal junction (Fig. 3, C and D). In addition, the percentage of T cells coexpressing these markers was increased in ACD biopsies (92/189, or 49%) relative to that in non-lesional biopsies (8/23, or 35%). To test whether β-arrestin signaling and G protein–biased signaling resulted in a similar effect on human T cell migration, we isolated leukocytes from peripheral blood and tested their chemotaxis to the biased agonists of CXCR3. Consistent with our observations in mice, the β-arrestin–biased agonist caused increased human effector memory CD8+ T cell migration relative to the G protein–biased agonist, but not in the case of CXCR3+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3, E and F and fig. S6). These findings are consistent with a similar role for CXCR3-mediated signaling through β-arrestin in T cells in human CHS responses.

Fig. 3. Human CXCR3+ T cells display differential responses to biased agonists of CXCR3, and CXCR3 and β-arrestin are coexpressed in T cell clusters within lesions from human allergen patch-tested skin.

(A) Diagram of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) patch testing. Colored regions on day 5 signify a positive response. (B) Representative immunohistochemistry of CXCR3 (green), CD3 (red), βarrestin (purple), and Hoechst (blue) in skin from human allergen patch-tested skin (+) and matched non-lesional (NL, –) controls from the same patient. Data are representative of three patient samples with similar results. Original magnification was x200 (left) and x400 with scale bar 100 μm and 50 μm, respectively. The white boxes in the x200 images indicate the area of magnified images in subsequent pictures and are located at the epidermal (epi)-dermal junction. In allergen patch-tested skin, this area was where most T-cell clusters were found, as previously described (66) whereas the same area in NL skin was devoid of such immune cell conglomerates and served as a control. (C and D) Quantitative analysis of the number of dermal CD3+ T cells (C) and co-expression of CD3 with CXCR3 and βarrestin (D) in skin from allergen patch-tested skin (ACD) and matched non-lesional (NL) controls from the same patient. (E and F) T cells isolated from patch-tested patients were tested for chemotaxis toward the indicated concentrations of the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 or the G protein–biased agonist VUF11418. (E) CXCR3+ CD8+ T cells (n=3) and (F) CD44+CD8+ cells (n=5). Patch test quantitative analyses are expressed as positive cells ± SEM from a microscopic field with six views at 400×, from a total of three patients. For (C) and (D), *P < 0.05 by unpaired two-tailed t-test. For (E) and (F), *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA.

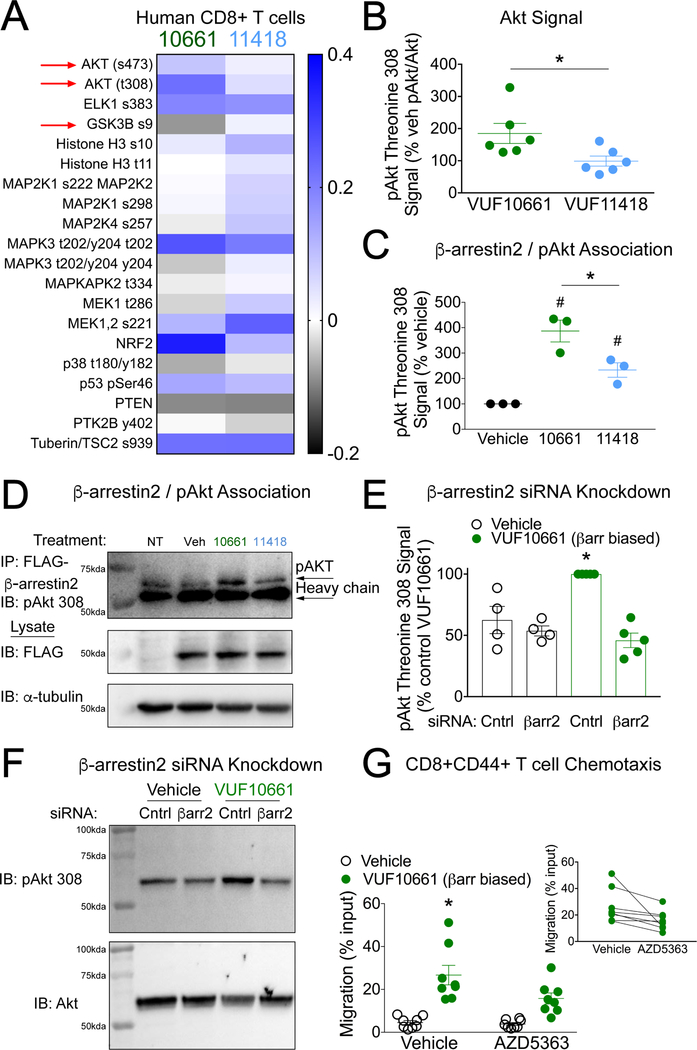

Akt is activated by β-arrestin and promotes T cell chemotaxis

Given the overlap of signaling pathways mediated by both β-arrestin and G proteins, it was unclear which specific signaling effectors downstream of β-arrestin were responsible for differences in chemotaxis and inflammation induced by β-arrestin– and G protein–biased agonists. To identify potential pathways, we performed a targeted flow cytometry-based analysis of intracellular phosphorylation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) after incubation with vehicle, VUF10661, or VUF11418. The Akt pathway, which can be activated by β-arrestin, displayed qualitative differences in these targeted analyses. The β-arrestin–biased agonist increased the phosphorylation of Akt residues Thr308 and Ser473, which are necessary for full-efficacy kinase activity, relative to the G protein–biased agonist (Fig. 4A). Differences in the phosphorylation of Ser9 of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), where phosphorylation at this site reduces the kinase activity of GSK-3β and is regulated in part by Akt, were also observed (Fig. 4A and fig. S7). We verified these differences in Akt phosphorylation in a T cell line (Jurkat cells) stably expressing CXCR3, observing increased Akt Thr308 phosphorylation by the β-arrestin–biased ligand VUF10661 relative to that induced by the G protein–biased ligand VUF11418 (Fig. 4B). Greater amounts of pAkt-Thr308 were coimmunoprecipitated with β-arrestin2 after CXCR3 activation with VUF10661 than after incubation with either VUF11418 or vehicle (Fig. 4, C and D and fig. S8). The siRNA-mediated knockdown of β-arrestin2 abolished the VUF10661-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt Thr308 (Fig. 4, E and F) and attenuated Akt Ser 473 phosphorylation (fig. S9). VUF10661 and VUF11418 did not stimulate differential phosphorylation of ERK (fig. S9), a kinase whose activity is increased by both G proteins and β-arrestins (42, 43). Consistent with the contribution of β-arrestin–mediated Akt activation to chemotaxis, pretreatment of lymphocytes with the Akt inhibitor AZD5363 decreased effector memory T cell chemotaxis toward VUF10661 (Fig. 4G). T cell chemotaxis toward VUF10661 was also inhibited by either the PI3K inhibitor LY20042 (fig. S10, A and B) or PTX (fig. S10, C and D). These findings are consistent with both PTX-sensitive G protein signaling and β-arrestin–mediated Akt signaling contributing to CXCR3-dependent chemotaxis.

Fig. 4. Akt activation is dependent on β-arrestin2 and promotes CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis.

(A) Selected heat map of the targeted analysis of intracellular phosphorylation events (log2 of the fold-change relative to vehicle) of human CD8+ T cells after stimulation with either VUF10661 (1 μM) or VUF11418 (1 μM) for fifteen minutes and normalized to vehicle-treated cells. Increased phosphorylation of Akt-activating sites Thr308 and Ser473 and decreased phosphorylation of the GSK-3β-inhibiting site Ser9 were observed after stimulation with VUF10661 (see fig. S7 for the full heat map). (B) Jurkat cells stably expressing CXCR3 were analyzed for the relative abundance of pAkt-Thr308 relative to that of total Akt after stimulation with the βarrestin-biased agonist VUF10661 (1 μM) or the G protein-biased agonist VUF11418 (1 μM) for 60 min. Data are from 6 experiments per condition. (C) HEK 293T cells expressing CXCR3 and FLAG-β-arrestin2 were analyzed for co-immunoprecipitation of pAkt-Thr308 with FLAG-βarrestin2 after 60 min of treatment with vehicle, VUF10661 (1 μM), or VUF11418 (1μM). Data are from three experiments per condition. (D) Representative co-immunoprecipitation and Western blots from the experiments described in (C). Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-β−arrestin2 was followed by Western blotting analysis of pAkt-Thr308 after 60 min of treatment with vehicle of the indicated agonist (1 μM). Blots are representative of three experiments. (E) HEK 293T cells expressing CXCR3 and treated with siRNA targeting β−arrestin2 or control siRNA were analyzed for the relative abundance of pAkt-Thr308 after 60 min of stimulation with VUF10661 (1 μM). Data are from four or five experiments per condition. (F) Representative Western blotting analysis of the siRNA-treated cells shown in (E). (G) WT mouce leukocytes were pretreated with the selective Akt inhibitor AZD5363 (100 nM) or vehicle, and then the chemotaxis of CD8+ T cells to VUF10661 (1 μM) was measured. Inset: a paired comparison between vehicle and AZD5363 conditions. Data are from 8 mice. For (B), *P < 0.05 by unpaired two-tailed t-test. For (C), *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc comparison; #P <0.05 compared to vehicle by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc comparison. For (E), *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA showing a statistically significant interaction of siRNA and ligand treatment followed by Tukey post hoc comparison of control siRNA-VUF10661 vs. β−arrestin2 siRNA-VUF10661. For (G), *P < 0.05 by repeated measures two-way ANOVA showing a statistically significant interaction of AZD5363 and VUF10661 followed by Tukey post hoc comparison of Vehicle-VUF10661 vs. AZD5363-VUF10661; P < 0.05. For (G, inset), P < 0.05 by paired two-tailed t-test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that small-molecule biased agonists of CXCR3 with similar receptor affinity but divergent G protein and β-arrestin efficacies caused distinct physiological effects on T cell–mediated skin inflammation through differential T cell chemotaxis. We found that a small-molecule, β-arrestin–biased agonist (VUF10661) was superior in promoting T cell chemotaxis compared to a G protein–biased agonist (VUF11418). Similar to previous studies, we found that both G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling were necessary for chemokine receptor–mediated chemotaxis (7, 23). These findings suggest that biased endogenous chemokines might promote distinct physiological effects, with clear relevance for drug discovery at CXCR3 and other chemokine receptors. For example, drugs designed to block the migration of CXCR3+ T cells to reduce inflammation should impair β-arrestin–mediated signaling, whereas drugs intended to increase the recruitment of CXCR3+ T cells, for example, in cancer immunotherapy, should promote signaling through both β-arrestin and Gαi. The distinct physiological effects caused by biased agonists offer a plausible reason for the difficulties in drugging chemokine receptors and also for biased signaling patterns encoded by different endogenous chemokines at the same receptor.

Given the roles of β-arrestin in the negative feedback of receptor signaling (desensitization and internalization), it was unclear how small molecules regulating complex G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling pathways would interact in physiologically relevant models of chemotaxis and inflammation. Our findings show that biased agonists of CXCR3 can differentially affect inflammatory processes. β-arrestins scaffold a number of effectors that control cell polarity and influence cellular migration (44–47); however, it was unclear which of these effectors were relevant to chemotaxis. Using targeted analysis of intracellular phosphorylation followed by hypothesis-driven experiments, we identified phosphorylation of Akt, which is promoted by β-arrestin signaling, as being necessary for full chemotactic function. Although PTX eliminated T cell chemotaxis, Akt inhibition did not fully inhibit migration, suggesting that multiple CXCR3-mediated pathways mediate T cell chemotaxis. Note that Akt has a well-established role in mediating cell polarity and migration. Akt translocates to the leading edge of migrating cells (48, 49), and this pathway is known to be red stimulated by endogenous CXCR3 chemokines (50, 51). Moreover, β-arrestin alters Akt activation through the formation of signaling complexes, such as with PP2A leading to Akt dephosphorylation downstream of the D2 dopamine receptor (52, 53), or with Src, in which both are phosphorylated and activated downstream of the insulin receptor (54). We found that the G protein–biased agonist failed to induce substantial chemotaxis above baseline, whereas at high concentrations it reduced migration below basal levels, which could be due to reduced Akt phosphorylation or off-target effects at high drug concentrations.

Despite previous studies that implicated both β-arrestin– and G protein–mediated signaling as being critical to cell function and migration downstream of other chemokine receptors, such as CXCR4 (7, 23, 55, 56), it was unclear how biased agonists could differentially affect physiological models of T cell movement and disease, if at all. Despite the fact that the β-arrestin–biased agonist caused greater CXCR3 internalization than did the G protein–biased agonist, the β-arrestin–biased agonist caused increased chemotaxis and potentiated a T cell–mediated inflammatory response. Consistent with studies of other chemokine receptors (18, 57), the fact that PTX eliminated CXCR3-mediated chemotaxis toward the β-arrestin–biased agonist implicates both G proteins as well as β-arrestins in chemotaxis. Studies classify CXCL11 as a β-arrestin–biased ligand relative to the other two CXCR3 endogenous ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 (8, 30). CXCL10 and CXCL11 bind to non-overlapping region(s) of CXCR3. In addition, CXCL11 binds to both G protein–coupled and PTX-uncoupled forms of CXCR3. In contrast, the relatively G protein–biased endogenous ligand CXCL10 has no affinity for the PTX-uncoupled form of CXCR3 (58), providing an illustrative example of multisite chemokine binding observed at CXCR3 (59). These data suggest that a different transducer, such as β-arrestin, may stabilize a distinct active receptor conformation when bound to CXCL11. Functionally, CXCL11 induces a greater chemotactic response than those induced by CXCL9 and CXCL10 (29, 60), which suggests that CXCL11 may be the most proinflammatory of the endogenous CXCR3 ligands. Consistent with β-arrestin playing a central role in T cell migration, we found that a β-arrestin–biased agonist was more effective than a G protein–biased agonist at increasing CXCR3-mediated T cell chemotaxis and enhancing a T cell–mediated inflammatory response. In addition, T cells isolated from β-arrestin2 KO mice displayed defective chemotaxis to an endogenous CXCR3 chemokine as evidenced by a ~10-fold decrease in potency, consistent with previous observations (23). Our data are consistent with a model in which the activation of β-arrestin–mediated signaling can increase T cell migration and function, whereas inhibiting either β-arrestin–mediated signaling or the association between β-arrestin and Akt would oppose migration and inflammation.

Based on our findings, it is perhaps unsurprising that small-molecule screens of CXCR3 ligands that focus primarily on receptor affinity or G protein–mediated signaling could potentially underperform in identifying promising preclinical agonists or antagonists. Indeed, the role of β-arrestin in other chemokine receptor signaling pathways suggests that an expanded screen to include the β-arrestin pathway (and potentially Akt) would improve candidate selection. In summary, targeting different CXCR3 pathways with biased agonists that have similar receptor affinities but different efficacies for G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling pathways produce distinct physiological differences in chemotaxis and contact hypersensitivity reactions, which has implications for drug development within the chemokine receptor family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The main research objectives of these studies were to investigate the physiological effects of biased agonists of CXCR3 and determine the mechanisms by which engagement of the β-arrestin–mediated signaling pathway potentiates chemotaxis and inflammation. These studies were performed with a combination of patient leukocytes, patient skin, genetically modified mice, and pharmacologic treatments supported by in vitro mechanistic data. The number of patients and animals used in each group for each experiment is reported in the figure legends. Animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups once their genotypes were confirmed, and investigators were blinded to mouse pharmacological treatments. Statistical details are provided at the end of this section and within the figure legends.

Small molecules and peptides

VUF10661 (Sigma-Aldrich), VUF11418 (Aobious), LY294002 (Sigma-Aldrich), and AZD5363 (Axon Med Chem) were dissolved in DMSO to make stock solutions and were stored at −20°C in a desiccator cabinet. Recombinant human CXCL11 and murine CXCL11 proteins (Peprotech) were diluted according to the manufacturer’s specifications and aliquots were stored at −80°C until needed for use.

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays

Intermolecular and intramolecular β-arrestin–based biosensor BRET experiments were performed as previously described (30) and similar to those outlined originally by the Bouvier laboratory (61, 62). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with CXCR3-Rluc together with plasmids encoding β-arrestin–YFP, GRK2-YFP, or GRK6-YFP and plated on a 96-well plate at ~50,000 cells per well (Corning) or with untagged CXCR3 and 50 ng of the Nanoluc-β-arrestin2-YFP biosensor, which was previously determined to be the optimal amount of biosensor expression vector (30). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with the compounds indicated in the figure legends in assay buffer consisting of HBSS supplemented with 20 mM HEPES and 3 μM coelenterazine-h (Promega). The plate was read by a Mithras LB940 instrument (Berthold, Germany), and the net BRET ratio was calculated by subtracting the YFP:Rluc ratio in vehicle-treated wells from the YFP:Rluc ratio in the ligand-stimulated wells. Cells tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

The DiscoveRx β-arrestin–dependent internalization assay

This assay was conducted as previously described (8) and in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, an Enzyme Acceptor-tagged βarrestin and a ProLink tag localized to endosomes were stably expressed in U2OS cells. The cells were transiently transfected with plasmid encoding untagged CXCR3. β-arrestin–mediated internalization resulted in the complementation of the two β-galactosidase enzyme fragments that hydrolyzed a substrate (DiscoveRx) to produce a chemiluminescent signal.

SRE/SRF pathway assay

SRE/SRF experiments were performed as previously described (30). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmid encoding CXCR3 and either the SRE or SRF luciferase reporters. Four hours later, the cells were plated on a 96-well plate at a concentration of ~25,000 cells/well. The next day, the cells were serum starved overnight, incubated with the compounds indicated in the figure legends for five hours, and subsequently lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferin was added to the lysate and the resulting luminescence was quantified using a Mithras LB940 instrument.

TGF-α–shedding assay

The ability of CXCR3 to stimulate Gαi activity was assessed by the TGF-α–shedding assay as previously described (63). Briefly, HEK 293 cells lacking Gαq, Gαi, Gαs, and Gα12/13 were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding CXCR3, a modified TGF–α-containing alkaline phosphatase (AP-TGF-α), and either the Gαq/i1,2 assay subunit [because Gαi2 is observed to be indispensable in CXCR3 signaling in T cells (64)] or, as a negative control, the subunit (which lacks the distal amino acid residues of G protein α-subunits required for recptor interaction) and were reseeded twenty-four hours later in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 5mM Hepes in a Costar 96-well plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Cells were then stimulated with the indicated concentration of ligand for 1 hour. Conditioned medium (CM) containing the shed AP-TGF-α was transferred to a new 96-well plate. Both the cell and CM plates were treated with para-nitrophenylphosphate (p-NPP, 100 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) substrate for one hour, which is converted to para-nitrophenol (p-NP) by AP-TGF-α. This activity was measured at OD405 in a Synergy Neo2 Hybrid Multi-Mode (BioTek) plate reader immediately after the addition of p-NPP addition and a 1-hour incubation. Gαi activity was calculated by first determining the amount of p-NP by absorbance through the following equation:

where and and represent the changes in absorbance after 1 hour in the cell and CM plates, respectively. Data were normalized to those from the vehicle-treated sample and the non-specific signal was subtracted from Gαi signal percentage AP-TGF-α release as follows:

Only the two highest concentrations of VUF11418 ligand (8 and 16 μM) resulted in consistent appreciable background signals, which resulted in larger errors relative to those from all other conditions (fig. S1G).

Generation of CXCR3+ Jurkat cells

Jurkat cells (an immortalized human CD4+ T cell line) stably expressing CXCR3 were generated by transfecting a linearized pcDNA3.1 expression vector encoding Geneticin (G-418) resistance, selecting for transfected cells with Geneticin (1000 μg/ml), and collecting cells that highly expressed CXCR3 by FACS. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 0.23% Glucose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and Geneticin (250 μg/ml).

Western blotting

Cells were serum-starved for at least 4 hours, incubated with the ligands indicated in the figure legends, subsequently washed once with ice-cold PBS, lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors [Phos-STOP (Roche), cOmplete EDTA free (Sigma)] for 15 min, sonicated, and cleared of insoluble debris by centrifugation at >12,000g at 4 °C for 15 min, after which the supernatant was collected. Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and analyzed by Western blotting at 4°C overnight with the indicated primary antibody. Antibodies against pERK (Cell Signaling Technology, #9106) and total ERK (Millipore #06–182) were used to assess ERK activation. Antibodies against pAkt-Thr308 (Cell Signaling Technology #13038), pAkt-Ser473 (Cell Signaling Technology #9271), and total Akt (Cell Signaling Technology #4691) were used to assess Akt phosphorylation. The A1-CT antibody, which recognizes both isoforms of β-arrestin, was kindly supplied by the laboratory of Robert J. Lefkowitz. Protein loading was assessed with an antibody against α-tubulin (Sigma #T6074). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated polyclonal mouse anti-rabbit-IgG or anti-mouse-IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Immune complexes on nitrocellulose membranes were imaged by SuperSignal enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher). After the detection of phosphorylated kinases, the nitrocellulose membranes were stripped and reblotted for total kinases. For quantification, band intensities corresponding to phosphorylated proteins were normalized to signals corresponding to the appropriate total protein on the same membrane with ImageLab software (Bio-Rad).

Immunoprecipitation

HEK 293N cells were cultured in 100-mm tissue culture plates and transiently transfected with 5 μg of CXCR3-encoding plasmid and 2.5 μg of plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged β-arrestin2 or were cultured in 6-well tissue culture plates and transfected with 1 μg of CXCR3-encoding plasmid and 0.5 μg of plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged β-arrestin 2. The cells were lysed as described earlier and the lysates were incubated for 4 hours at 4°C with anti-FLAG magnetic beads (Thermo Fischer) and washed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were then immediately eluted with 2x SDS and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting as described earlier.

siRNA-mediated knockdown

HEK 293N cells in 6-well tissue culture plates were transiently transfected with 1 μg of plasmid encoding CXCR3A and 3.5 μg of either control siRNA or with previously validated β-arrestin2–specific siRNA (“wem2”) (65) with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher) as per the manufacturer’s specifications. Seventy-two hours later, the cells were stimulated with 1 μM VUF10661 for 60 minutes and the cells were then lysed and analyzed by Western blotting as described earlier.

Study subjects and skin samples

All studies involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University Health System. Study participation inclusion was offered to patients undergoing patch testing in a specialty contact dermatitis clinic. Inclusion criteria were ≥18 years of age and completion of patch testing. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, topical corticosteroids at patch site, oral corticosteroids, systemic immunosuppressants, phototherapy, known bleeding disorders and allergy to lidocaine or epinephrine. Skin biopsies and venipunctures were obtained from male and female volunteers under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University. Patches containing test allergens were applied to study participants on day 1, removed on day 3, and analyzed after 96 to 120 hours. If a study participant had a positive patch test, then a 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at the positive test site and a 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a negative site (normal skin) from normal regions of the skin nearby. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed as previously described (66). Preceding cell counting, skin images from allergen patch-tested skin and matched non-lesional (NL) controls from the same patient were separated by color channel. All collected images were processed with ImageJ software. The ImageJ cell counter tool recorded mouse clicks on cells that were labeled with colored dots. Cell numbers were expressed as counts per view in a microscopic field with 6 views.

Mice

Wild-type C57BL/6; C57BL/6 CXCR3−/0, CXCR3−/−; and C57BL/6 ARRB2 −/− mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions in accredited animal facilities at the Duke University. C57BL/6 CXCR3−/0, CXCR3−/− mice were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory (Maine, USA, stock # 005796) and C57BL/6 ARRB2 −/− were kindly provided by Robert J Lefkowitz (Duke University, USA). Mice were between six and fifteen weeks of age when first used.

Mouse allergic CHS

Mice were sensitized by topical application of 50 μl of 0.5% DNFB (Sigma-Aldrich) in 4:1 acetone/olive oil on their shaved back and were challenged on their ears 4 days later with 10 μl of 0.3% DNFB or vehicle control. Then, 4, 24, and 48 hours later, 10 μl of either vehicle, VUF10661 (50 μM), or VUF11418 (50 μM) dissolved in 72:18:10 acetone:olive oil:DMSO was topically applied to the indicated ear by an investigator blinded to treatment. Ear thickness was measured at different time points with an engineer’s micrometer (Standard Gage).

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotaxis assays were conducted similarly to those previously described (57). Briefly, mouse leukocytes, obtained by passing cells isolated from the spleen and subjected to erythrocyte lysis through a 70-μm filter, were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS. For the assay, 1 × 106 cells in 100 μl of medium were added to the top chamber of a 6.5 mm diameter, 5-μm pore polycarbonate Transwell insert (Costar) and incubated in duplicate with the indicated concentrations of ligand suspended in 600 μl of the medium in the bottom chamber for 2 hours at 37°C. Cells that migrated to the bottom chamber were resuspended, washed, stained with a Live/Dead marker (Aqua Dead, ThermoFisher) and antibodies to cell surface markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD44, and CD45), fixed with paraformaldehyde, and subjected to cell counting flow cytometric analysis with a BD LSRII Flow cytometer. Flow cytometry was performed in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Research Flow Cytometry Facility (Durham, NC). We were unable to identify a reliable anti-murine CXCR3 antibody for flow cytometry suitable for surface staining. CountBright beads (ThermoFisher) were added immediately after bottom chamber resuspension to correct for differences in final volume and any sample loss during wash steps. A 1:10 dilution of input cells was similarly analyzed. Migration was calculated by dividing the number of migrated cells by the number of input cells. In some studies, cells were pre-incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with 100 ng/mL PTX (List Biological Laboratories), 100 μM LY 294002 (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit PI3K, or 100 nM AZD 5363 (Axon Med Chem) to inhibit Akt. Human peripheral blood leukocytes were obtained by venipuncture in accordance with the Duke Institutional Review Board, subjected to erythrocyte lysis, and assayed as described earlier, with the addition of an anti-human CXCR3 antibody. For some samples, reliable anti-human CXCR3 staining was not obtained, which resulted in two fewer replicates in the CD8+CXCR3+ group compared to the CD8+CD44+ group. Analysis was conducted with FlowJo (Ashland, OR) Version 10 software. A representative gating tree is shown in fig. S11.

Assessment of T cells in the skin

Mice were subjected to the mouse allergic CHS assay as described earlier, with the exception that both ears received 0.3% DNFB to induce inflammation. Two ears were pooled from a single mouse to produce one biological replicate. Approximately 4 hours after the last topical drug treatment, mouse ears were dissected and transferred dorsal side up to a dish containing ice-cold PBS. Dorsal and ventral layers were separated and added to 5 mL of digestion media consisting of HBSS supplemented with 5% FBS (Corning), 10 mM HEPES, 0.04 mg/ml liberase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.3 mg/ml DNAse (Sigma-Aldrich). Ears were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, minced, and incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C, vortexing gently every 10 min. After 40 min, 25 mL of PBS was added and the sample was vortexed and strained through a 70-μm mesh into a fresh 50 mL conical tube. Cells were spun down at 200g at 4°C and resuspended in PBS supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% BSA. To obtain leukocyte cell counts, cells were manually counted with Turks solution an investigator blinded to treatment group. Cells were transferred to round-bottom FACS tubes, washed twice with 2 mL of ice-cold PBS, and stained with a Live/Dead marker (Aqua Dead, Thermo Fisher # L34957). Cells were blocked in PBS supplemented with 3% FBS and 10 mM EDTA (FACS buffer) with anti-CD16/32 (Fcγ-block), 5% normal mouse serum (Thermo Fisher), and 5% normal rat serum (Thermo Fisher). Cells were then stained with antibodies to cell surface markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD44, and CD45) for 30 min at 4°C, washed with FACS buffer, and fixed with 0.4% paraformaldehyde. Foxp3 intracellular staining was performed with an anti-Foxp3 antibody using a Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Flow cytometry was performed in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Research Flow Cytometry Facility on a BD LSRII Flow cytometer (Durham, NC). Analysis was conducted with FlowJo Version 10 software. Total cells were calculated by multiplying the relative abundance of total live cells by the manual leukocyte count. A list of flow cytometry antibodies utilized are listed in Table S2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of human skin

Sections of frozen human specimens were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-human CD3 (OKT3, Biolegend) and anti-human βarrestin (kindly provided by Robert J Lefkowitz), which was followed by reaction with Cy3- and Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated mouse IgG1 antibodies against human CXCR3 (R&D Systems, Inc.) or mouse IgG1 Isotype Control (Tonbo Biosciences). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342, washed in PBS, and mounted with Anti-fade Mounting Media (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Targeted phosphoprotein analysis

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with saturating concentrations of the ligands indicated in the figure legends for 1, 2, 5, or 15 min, fixed with 1% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, and were prepared for antibody staining as previously described (67). Briefly, the fixed cells were permeabilized in 90% methanol for 15 min. The cells were then stained with a panel of antibodies specific to the markers indicated in the figure (Primity Bio Pathway Phenotyping service) and analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The log2 ratio of the MFI of the stimulated samples divided by that of the unstimulated control samples was calculated as a measure of the response.

Statistical analyses

Dose-response curves were fitted to a log agonist versus stimulus with four parameters (Span, Baseline, Hill coefficient, and EC50) with the minimum baseline constrained to zero using Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad). To compare ligands in concentration-response assays or time-response assays, a two-way ANOVA of ligand and concentration or ligand and time, respectively, was conducted. If a statistically significant interaction or main effect of treatment, depending on the experiment, was observed (P < 0.05), then comparative two-way ANOVAs between individual ligands were performed. Further details of statistical analysis and replicates are included in the figure legends. For mouse ear T cell counts, two mice corresponding to the highest and lowest values in the wild-type VUF10661 treatment group were excluded from analysis (CD8+CD44+ counts 79515 and 2709, respectively). Lines indicate the mean and error bars signify the standard error of the mean (SEM) throughout the manuscript, unless otherwise noted. * indicates P < 0.05 throughout the paper to indicate statistical significance from pertinent comparisons detailed in the figure legends, unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank R. J. Lefkowitz (Duke University, USA) for guidance, mentorship, thoughtful feedback throughout this work and for supplying C57BL/6 ARRB2 −/− mice; R. Premont (Harrington Discovery Institute, USA) for kindly providing the GRK-YFP constructs; A. Inoue (Tohoku University, Japan) for G protein knockout cells; M. Caron, S. Shenoy, and N. Freedman for the use of laboratory equipment; T. Pack, A. Wisdom, and M.-N. Huang for many helpful discussions; N. Nazo for laboratory assistance; and K. Hines and K. Scoggins for assistance in patient sample acquisition.

Funding: This work was supported by T32GM7171 (J.S.S.), the Duke Medical Scientist Training Program (J.S.S.), 1R01GM122798–01A1 (S.R.), K08HL114643–01A1, (S.R.), Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists (S.R.), R21AI28727 (A.S.M.), R01AI39207 (A.S.M.), Duke Physician-Scientist Strong Start Award (A.S.M.), Dermatology Foundation Research Grant (A.S.M.), and the Duke Pinnell Center for Investigative Dermatology (J.S.S., A.S.M., and S.R.).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Schall TJ, Proudfoot AE, Overcoming hurdles in developing successful drugs targeting chemokine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 11, 355–363 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groom JR, Luster AD, CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions. Immunology and cell biology 89, 207–215 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogura M, Ishida T, Hatake K, Taniwaki M, Ando K, Tobinai K, Fujimoto K, Yamamoto K, Miyamoto T, Uike N, Tanimoto M, Tsukasaki K, Ishizawa K, Suzumiya J, Inagaki H, Tamura K, Akinaga S, Tomonaga M, Ueda R, Multicenter phase II study of mogamulizumab (KW-0761), a defucosylated anti-cc chemokine receptor 4 antibody, in patients with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 32, 1157–1163 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos R, Ursu O, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Donadi RS, Bologa CG, Karlsson A, Al-Lazikani B, Hersey A, Oprea TI, Overington JP, A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 19–34 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani A, The chemokine system: redundancy for robust outputs. Immunol Today 20, 254–257 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strungs EG, Luttrell LM, Arrestin-dependent activation of ERK and Src family kinases. Handb Exp Pharmacol 219, 225–257 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drury LJ, Ziarek JJ, Gravel S, Veldkamp CT, Takekoshi T, Hwang ST, Heveker N, Volkman BF, Dwinell MB, Monomeric and dimeric CXCL12 inhibit metastasis through distinct CXCR4 interactions and signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 17655–17660 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajagopal S, Bassoni DL, Campbell JJ, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Wehrman TS, Biased agonism as a mechanism for differential signaling by chemokine receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry 288, 35039–35048 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zidar DA, Violin JD, Whalen EJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Selective engagement of G protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) encodes distinct functions of biased ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 9649–9654 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, Roth BL, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Miller KJ, Spedding M, Mailman RB, Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320, 1–13 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JS, Rajagopal S, The beta-Arrestins: Multifunctional Regulators of G Protein-coupled Receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry 291, 8969–8977 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soergel DG, Subach RA, Burnham N, Lark MW, James IE, Sadler BM, Skobieranda F, Violin JD, Webster LR, Biased agonism of the mu-opioid receptor by TRV130 increases analgesia and reduces on-target adverse effects versus morphine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Pain 155, 1829–1835 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manglik A, Lin H, Aryal DK, McCorvy JD, Dengler D, Corder G, Levit A, Kling RC, Bernat V, Hubner H, Huang XP, Sassano MF, Giguere PM, Lober S, Da D, Scherrer G, Kobilka BK, Gmeiner P, Roth BL, Shoichet BK, Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 537, 185–190 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brust TF, Morgenweck J, Kim SA, Rose JH, Locke JL, Schmid CL, Zhou L, Stahl EL, Cameron MD, Scarry SM, Aube J, Jones SR, Martin TJ, Bohn LM, Biased agonists of the kappa opioid receptor suppress pain and itch without causing sedation or dysphoria. Sci Signal 9, ra117 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monasky MM, Taglieri DM, Henze M, Warren CM, Utter MS, Soergel DG, Violin JD, Solaro RJ, The beta-arrestin-biased ligand TRV120023 inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy while preserving enhanced myofilament response to calcium. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 305, H856–866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JS, Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal S, Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat Rev Drug Discov, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Schmid CL, Kennedy NM, Ross NC, Lovell KM, Yue Z, Morgenweck J, Cameron MD, Bannister TD, Bohn LM, Bias Factor and Therapeutic Window Correlate to Predict Safer Opioid Analgesics. Cell 171, 1165–1175 e1113 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC, Pertussis toxin inhibits migration of B and T lymphocytes into splenic white pulp cords. J Exp Med 182, 581–586 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thelen M, Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nat Immunol 2, 129–134 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohout TA, Nicholas SL, Perry SJ, Reinhart G, Junger S, Struthers RS, Differential desensitization, receptor phosphorylation, beta-arrestin recruitment, and ERK1/2 activation by the two endogenous ligands for the CC chemokine receptor 7. The Journal of biological chemistry 279, 23214–23222 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orsini MJ, Parent JL, Mundell SJ, Marchese A, Benovic JL, Trafficking of the HIV coreceptor CXCR4. Role of arrestins and identification of residues in the c-terminal tail that mediate receptor internalization. The Journal of biological chemistry 274, 31076–31086 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aramori I, Ferguson SS, Bieniasz PD, Zhang J, Cullen B, Cullen MG, Molecular mechanism of desensitization of the chemokine receptor CCR-5: receptor signaling and internalization are dissociable from its role as an HIV-1 co-receptor. EMBO J 16, 4606–4616 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong AM, Premont RT, Richardson RM, Yu YR, Lefkowitz RJ, Patel DD, Defective lymphocyte chemotaxis in beta-arrestin2- and GRK6-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 7478–7483 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, Smylie M, Dummer R, Hill A, Hogg D, Haanen J, Carlino MS, Bechter O, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, Guidoboni M, McArthur G, Lebbe C, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Cebon J, Sosman J, Postow MA, Callahan MK, Walker D, Rollin L, Bhore R, Hodi FS, Larkin J, Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.van Wanrooij EJ, de Jager SC, van Es T, de Vos P, Birch HL, Owen DA, Watson RJ, Biessen EA, Chapman GA, van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J, CXCR3 antagonist NBI-74330 attenuates atherosclerotic plaque formation in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 28, 251–257 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, Harris TH, Dresser K, Su MW, Zhou Y, Deng A, Hunter CA, Luster AD, Harris JE, CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med 6, 223ra223 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richmond JM, Masterjohn E, Chu R, Tedstone J, Youd ME, Harris JE, CXCR3 Depleting Antibodies Prevent and Reverse Vitiligo in Mice. J Invest Dermatol 137, 982–985 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flier J, Boorsma DM, Bruynzeel DP, Van Beek PJ, Stoof TJ, Scheper RJ, Willemze R, Tensen CP, The CXCR3 activating chemokines IP-10, Mig, and IP-9 are expressed in allergic but not in irritant patch test reactions. J Invest Dermatol 113, 574–578 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colvin RA, Campanella GS, Sun J, Luster AD, Intracellular domains of CXCR3 that mediate CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 function. The Journal of biological chemistry 279, 30219–30227 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith JS, Alagesan P, Desai NK, Pack TF, Wu JH, Inoue A, Freedman NJ, Rajagopal S, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 3 Splice Variants Differentially Activate Beta-Arrestins to Regulate Downstream Signaling Pathways. Mol Pharmacol, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rajagopal S, Bassoni DL, Campbell JJ, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Wehrman TS, Biased Agonism as a Mechanism for Differential Signaling by Chemokine Receptors. J Biol Chem, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Stroke IL, Cole AG, Simhadri S, Brescia MR, Desai M, Zhang JJ, Merritt JR, Appell KC, Henderson I, Webb ML, Identification of CXCR3 receptor agonists in combinatorial small-molecule libraries. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 349, 221–228 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholten DJ, Wijtmans M, van Senten JR, Custers H, Stunnenberg A, de Esch IJ, Smit MJ, Leurs R, Pharmacological characterization of [3H]VUF11211, a novel radiolabeled small-molecule inverse agonist for the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Mol Pharmacol 87, 639–648 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijtmans M, Scholten DJ, Roumen L, Canals M, Custers H, Glas M, Vreeker MC, de Kanter FJ, de Graaf C, Smit MJ, de Esch IJ, Leurs R, Chemical subtleties in small-molecule modulation of peptide receptor function: the case of CXCR3 biaryl-type ligands. J Med Chem 55, 10572–10583 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholten DJ, Canals M, Wijtmans M, de Munnik S, Nguyen P, Verzijl D, de Esch IJ, Vischer HF, Smit MJ, Leurs R, Pharmacological characterization of a small-molecule agonist for the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Br J Pharmacol 166, 898–911 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berchiche YA, Sakmar TP, CXC Chemokine Receptor 3 Alternative Splice Variants Selectively Activate Different Signaling Pathways. Mol Pharmacol 90, 483–495 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sebastiani S, Albanesi C, Nasorri F, Girolomoni G, Cavani A, Nickel-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells display distinct migratory responses to chemokines produced during allergic contact dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 118, 1052–1058 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung R, Malik M, Ravyn V, Tomkowicz B, Ptasznik A, Collman RG, An arrestin-dependent multi-kinase signaling complex mediates MIP-1beta/CCL4 signaling and chemotaxis of primary human macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 86, 833–845 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeFea KA, Stop that cell! Beta-arrestin-dependent chemotaxis: a tale of localized actin assembly and receptor desensitization. Annual review of physiology 69, 535–560 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solari R, Pease JE, Begg M, “Chemokine receptors as therapeutic targets: Why aren’t there more drugs?”. Eur J Pharmacol 746, 363–367 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavani A, Mei D, Guerra E, Corinti S, Giani M, Pirrotta L, Puddu P, Girolomoni G, Patients with allergic contact dermatitis to nickel and nonallergic individuals display different nickel-specific T cell responses. Evidence for the presence of effector CD8+ and regulatory CD4+ T cells. J Invest Dermatol 111, 621–628 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tohgo A, Choy EW, Gesty-Palmer D, Pierce KL, Laporte S, Oakley RH, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM, The stability of the G protein-coupled receptor-beta-arrestin interaction determines the mechanism and functional consequence of ERK activation. The Journal of biological chemistry 278, 6258–6267 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 279, 35518–35525 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nichols HL, Saffeddine M, Theriot BS, Hegde A, Polley D, El-Mays T, Vliagoftis H, Hollenberg MD, Wilson EH, Walker JK, DeFea KA, beta-Arrestin-2 mediates the proinflammatory effects of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in the airway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 16660–16665 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zoudilova M, Min J, Richards HL, Carter D, Huang T, DeFea KA, beta-Arrestins scaffold cofilin with chronophin to direct localized actin filament severing and membrane protrusions downstream of protease-activated receptor-2. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 14318–14329 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ge L, Ly Y, Hollenberg M, DeFea K, A beta-arrestin-dependent scaffold is associated with prolonged MAPK activation in pseudopodia during protease-activated receptor-2-induced chemotaxis. The Journal of biological chemistry 278, 34418–34426 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunton DL, Barnes WG, Kim J, Ren XR, Violin JD, Reiter E, Milligan G, Patel DD, Lefkowitz RJ, Beta-arrestin 2-dependent angiotensin II type 1A receptor-mediated pathway of chemotaxis. Mol Pharmacol 67, 1229–1236 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meili R, Ellsworth C, Lee S, Reddy TB, Ma H, Firtel RA, Chemoattractant-mediated transient activation and membrane localization of Akt/PKB is required for efficient chemotaxis to cAMP in Dictyostelium. EMBO J 18, 2092–2105 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morales-Ruiz M, Lee MJ, Zollner S, Gratton JP, Scotland R, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Hla T, Sessa WC, Sphingosine 1-phosphate activates Akt, nitric oxide production, and chemotaxis through a Gi protein/phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 276, 19672–19677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zohar Y, Wildbaum G, Novak R, Salzman AL, Thelen M, Alon R, Barsheshet Y, Karp CL, Karin N, CXCL11-dependent induction of FOXP3-negative regulatory T cells suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest 124, 2009–2022 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonacchi A, Romagnani P, Romanelli RG, Efsen E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Francalanci M, Serio M, Laffi G, Pinzani M, Gentilini P, Marra F, Signal transduction by the chemokine receptor CXCR3: activation of Ras/ERK, Src, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt controls cell migration and proliferation in human vascular pericytes. The Journal of biological chemistry 276, 9945–9954 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beaulieu JM, Marion S, Rodriguiz RM, Medvedev IO, Sotnikova TD, Ghisi V, Wetsel WC, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, A beta-arrestin 2 signaling complex mediates lithium action on behavior. Cell 132, 125–136 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luan B, Zhao J, Wu H, Duan B, Shu G, Wang X, Li D, Jia W, Kang J, Pei G, Deficiency of a beta-arrestin-2 signal complex contributes to insulin resistance. Nature 457, 1146–1149 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lagane B, Chow KY, Balabanian K, Levoye A, Harriague J, Planchenault T, Baleux F, Gunera-Saad N, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F, CXCR4 dimerization and beta-arrestin-mediated signaling account for the enhanced chemotaxis to CXCL12 in WHIM syndrome. Blood 112, 34–44 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quoyer J, Janz JM, Luo J, Ren Y, Armando S, Lukashova V, Benovic JL, Carlson KE, Hunt SW 3rd, Bouvier M, Pepducin targeting the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 acts as a biased agonist favoring activation of the inhibitory G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E5088–5097 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunn MD, Tangemann K, Tam C, Cyster JG, Rosen SD, Williams LT, A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 258–263 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cox MA, Jenh CH, Gonsiorek W, Fine J, Narula SK, Zavodny PJ, Hipkin RW, Human interferon-inducible 10-kDa protein and human interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant are allotopic ligands for human CXCR3: differential binding to receptor states. Mol Pharmacol 59, 707–715 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kleist AB, Getschman AE, Ziarek JJ, Nevins AM, Gauthier PA, Chevigne A, Szpakowska M, Volkman BF, New paradigms in chemokine receptor signal transduction: Moving beyond the two-site model. Biochem Pharmacol 114, 53–68 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colvin RA, Campanella GS, Manice LA, Luster AD, CXCR3 requires tyrosine sulfation for ligand binding and a second extracellular loop arginine residue for ligand-induced chemotaxis. Mol Cell Biol 26, 5838–5849 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charest PG, Terrillon S, Bouvier M, Monitoring agonist-promoted conformational changes of beta-arrestin in living cells by intramolecular BRET. EMBO Rep 6, 334–340 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Angers S, Salahpour A, Joly E, Hilairet S, Chelsky D, Dennis M, Bouvier M, Detection of beta 2-adrenergic receptor dimerization in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 3684–3689 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inoue A, Ishiguro J, Kitamura H, Arima N, Okutani M, Shuto A, Higashiyama S, Ohwada T, Arai H, Makide K, Aoki J, TGFalpha shedding assay: an accurate and versatile method for detecting GPCR activation. Nat Methods 9, 1021–1029 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson BD, Jin Y, Wu KH, Colvin RA, Luster AD, Birnbaumer L, Wu MX, Inhibition of G alpha i2 activation by G alpha i3 in CXCR3-mediated signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 9547–9555 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drake MT, Violin JD, Whalen EJ, Wisler JW, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ, beta-arrestin-biased agonism at the beta2-adrenergic receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 283, 5669–5676 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suwanpradid J, Shih M, Pontius L, Yang B, Birukova A, Guttman-Yassky E, Corcoran DL, Que LG, Tighe RM, MacLeod AS, Arginase1 Deficiency in Monocytes/Macrophages Upregulates Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase To Promote Cutaneous Contact Hypersensitivity. J Immunol 199, 1827–1834 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moraga I, Wernig G, Wilmes S, Gryshkova V, Richter CP, Hong WJ, Sinha R, Guo F, Fabionar H, Wehrman TS, Krutzik P, Demharter S, Plo I, Weissman IL, Minary P, Majeti R, Constantinescu SN, Piehler J, Garcia KC, Tuning cytokine receptor signaling by re-orienting dimer geometry with surrogate ligands. Cell 160, 1196–1208 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parham P, Immunology: adaptable innate killers. Nature 441, 415–416 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.