Abstract

Dysregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activity results in uncontrolled inflammation, which underlies many chronic diseases. Although mitochondrial damage is needed for the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, it is unclear how macrophages are able to respond to structurally diverse inflammasome-activating stimuli. Here we show that the synthesis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), induced after the engagement of Toll-like receptors, is crucial for NLRP3 signalling. Toll-like receptors signal via the MyD88 and TRIF adaptors to trigger IRF1-dependent transcription of CMPK2, a rate-limiting enzyme that supplies deoxyribonucleotides for mtDNA synthesis. CMPK2-dependent mtDNA synthesis is necessary for the production of oxidized mtDNA fragments after exposure to NLRP3 activators. Cytosolic oxidized mtDNA associates with the NLRP3 inflammasome complex and is required for its activation. The dependence on CMPK2 catalytic activity provides opportunities for more effective control of NLRP3 inflammasome-associated diseases.

Inflammation is initiated by the sensing of pathogen-associated or damage-associated molecular patterns1,2. Among pattern-recognition receptors, NLRP3 is unique in its response to highly diverse extracellular stimuli, several of which link tissue damage to sterile inflammation, the goal of which is damage repair3,4. After stimulation, NLRP3 is thought to expose its pyrin domain, which binds ASC (apoptosis- associated speck-like protein) that recruits the effector molecule pro-caspase-1 via CARD–CARD interactions to form a large cytosolic complex—the NLRP3 inflammasome1,2,5. Inflammasome assembly triggers the self-cleavage and activation of caspase-1, converting pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to their mature forms1. Persistent and aberrant NLRP3 signalling underlies many chronic and degenerative diseases, including periodic auto-inflammatory syndromes, gout, osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, lupus, macular degeneration and cancer6,7. To our knowledge, there are currently no effective, safe and selective therapeutic approaches to these diseases that allow the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activity.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation depends on two functionally distinct steps: ‘priming’ and ‘activation’1,4,8. Priming involves the direct engagement of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) by pathogen-associated or damage-associated molecular patterns, resulting in the rapid activation of NF-κB, which stimulates pro-IL-1β synthesis and increased expression of NLRP3. The activation step is less clear, leading to NLRP3 inflammasome assembly followed by caspase-1 activation1,5,8. A major difficulty in understanding the activation step is the abrupt transition from priming to activation that is triggered by chemically and structurally diverse stimuli (for example, microparticles, pore-forming toxins, ATP and certain pathogens), often referred to as NLRP3 activators, although none of them binds to NLRP3 directly1,9. One solution to the activation conundrum is the proposal that NLRP3 activators operate through a common intracellular intermediate, most likely the mitochondrion10–12. Through different mechanisms that may involve plasma membrane rupture, K+ efflux and increased intracellular Ca2+, NLRP3 activators elicit a particular form of mitochondrial damage that causes the release of fragmented mtDNA and the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that convert mtDNA to an oxidized form (ox-mtDNA), proposed to serve as the ultimate NLRP3 ligand, or at least a part of it13. Mitochondrial damage induced by NLRP3 activators is distinct from that induced by pro-apoptotic BCL2 proteins, which enable the release of cytochrome c and activation of the apoptotic protease activating factor complex to activate caspase-3, rather than caspase-114. Of note, mitochondrial damage alone does not trigger NLRP3 signalling if priming is omitted9. It is not known, however, whether and how macrophage priming affects the mitochondrion and makes it more capable of producing ox-mtDNA to allow NLRP3 inflammasome activation13.

LPS induces macrophage mtDNA replication

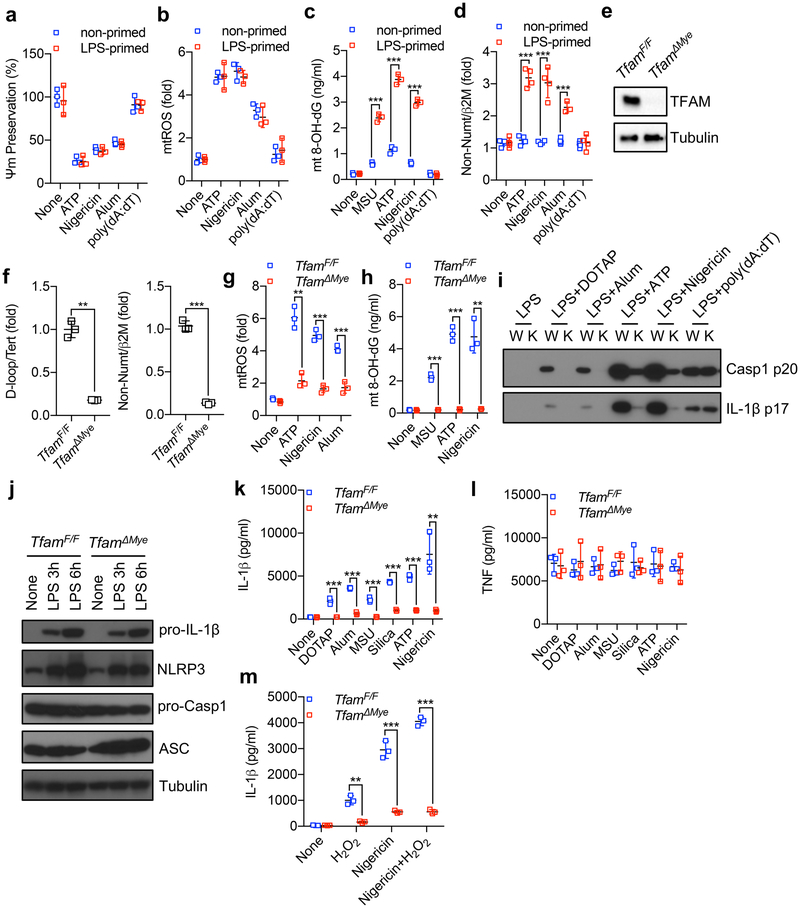

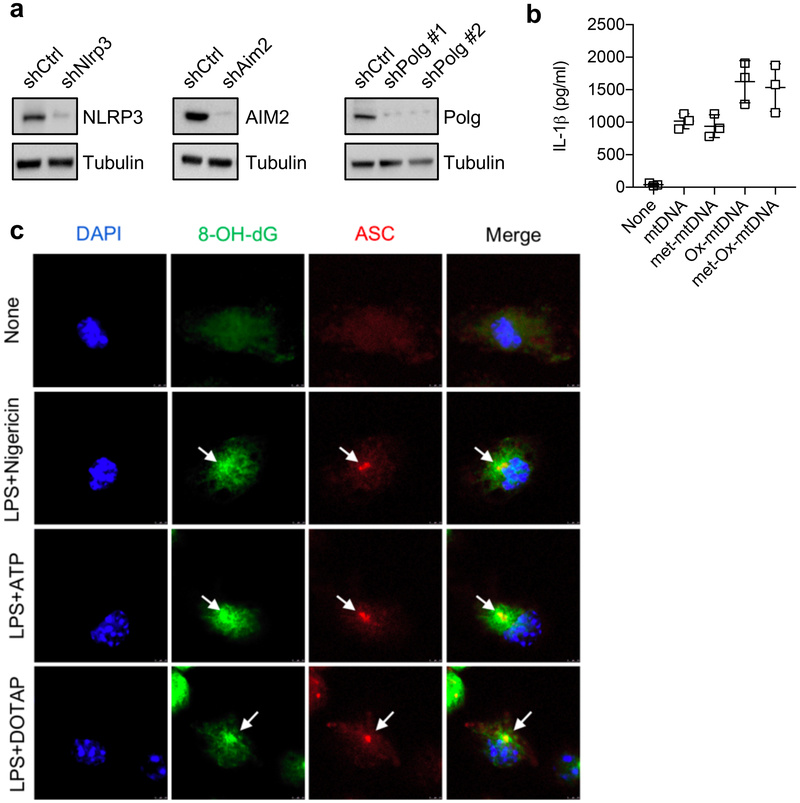

The exposure of macrophages to NLRP3 activators results in mitochondrial damage, measurable by a drop in mitochondrial membrane potential and increased production of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). Without previous priming, NLRP3 activators did not elicit extensive mtDNA oxidation or its cytoplasmic release (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). Unlike NLRP3 activators, an AIM2 agonist, poly(dA-dT), did not induce mitochondrial damage, mtDNA oxidation or cytosolic mtDNA release (Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). These results suggest that macrophage priming affects the ability of mitochondria that were damaged after exposure to NLRP3 activators to produce ox-mtDNA and release mtDNA fragments to the cytosol. We and others have shown that mtDNA depletion by chronic treatment with low-dose ethidium bromide prevented NLRP3 inflammasome activation10,11. To establish genetically the role of mtDNA in NLRP3 inflammasome activation we crossed LysM-cre and Tfamf/f mice15 to generate TfamΔMye mice that specifically lack TFAM (transcription factor A, mitochondrial) in myeloid cells (Extended Data Fig. 1e). TFAM binds mtDNA to promote its compaction and stabilization as well as replication and transcription16. Tfam ablation markedly reduced mtDNA content in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Extended Data Fig. 1f). TfamΔMye BMDMs did not produce mtROS and ox-mtDNA in response to NLRP3 activators and displayed defective caspase-1 activation and IL-1β processing, while retaining normal pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 induction, expression of general inflammasome components, normal AIM2 inflammasome activation and unaltered TNF expression (Extended Data Fig. 1g–l). To determine whether mtDNA oxidation is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we incubated TfamΔMye BMDMs with hydrogen peroxide, the predominant ROS in activated macrophages, and assessed whether this rescues defective NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Notably, hydrogen peroxide, which induced IL-1β release in Tfamf/f BMDMs, failed to restore NLRP3 inflammasome activation in TFAM-deficient cells even in combination with nigericin (Extended Data Fig. 1m), suggesting that mtROS trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation by promoting the production of ox-mtDNA. To further rule out the possibility that TFAM itself rather than mtDNA is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we synthesized a 90-base-pair (bp) DNA fragment encompassing the D-loop (origin of mtDNA replication; also known as mt-Dcr) region of mouse mtDNA in the presence of the oxidized nucleotide 8-OH-dGTP. Transfection of synthetic D-loop ox-mtDNA into lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-primed TfamΔMye BMDMs induced IL-1β production without any known NLRP3 activator (Fig. 1a). The effect was dependent on NLRP3, but not on AIM2 (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a), demonstrating that TFAM promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating ox-mtDNA formation or release. Transfection of oxidized nuclear DNA of the same length (90 bp) also resulted in IL-1β production (Fig. 1a), indicating that NLRP3 detects specific nucleotide alteration(s) rather than DNA sequence or its cellular source. Indeed, replacement of 8-OH-dGTP with dGTP during in vitro DNA synthesis led to AIM2, but not NLRP3, inflammasome activation (fig 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Neither form of DNA affected TNF synthesis (Fig. 1a). Cytosine methylation had no effect on the ability of DNA to activate inflammasome (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Finally, we confirmed that endogenous ox-mtDNA co-localizes with ASC-containing inflammasome complexes after NLRP3 activator treatment (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

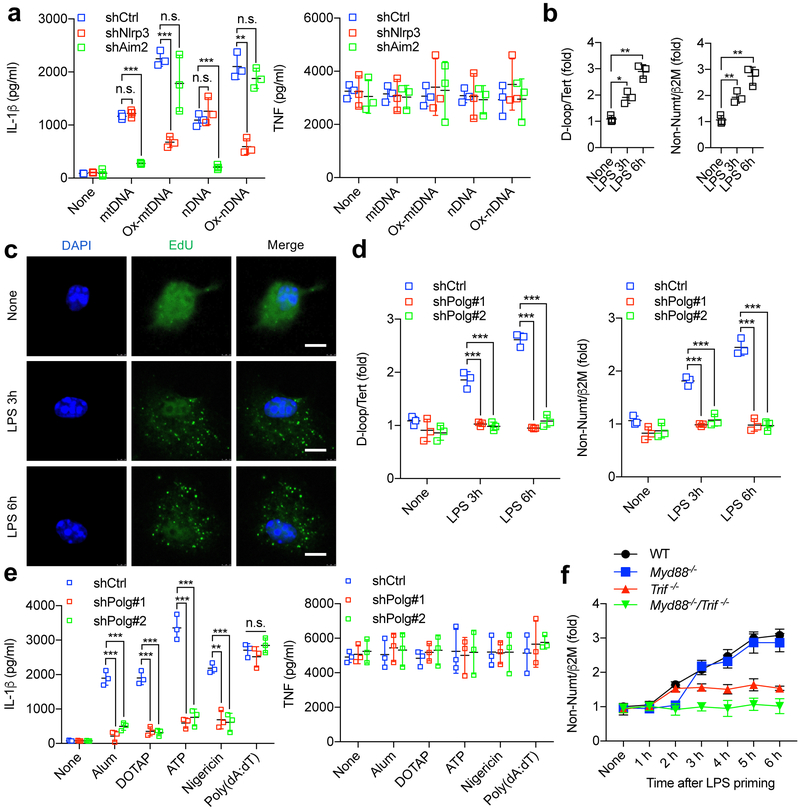

Fig. 1 ~. Newly synthesized mtDNA is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, TfamΔMye BMDMs transduced with shRNA against Nlrp3, Aim2 (shNlrp3, shAim2) or control shRNA (shCtrl) and primed with LPS were incubated with synthetic mtDNA, ox-mtDNA, nuclear DNA (nDNA) or oxidized nuclear DNA (ox-nDNA), and the release of IL-1β (left) and TNF (right) was measured 4 h later. b, Relative total mtDNA amounts were quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with primers specific for the mitochondrial D-loop region or a region of mtDNA that is not inserted into nuclear DNA (non-NUMT) and primers specific for nDNA (Tert, B2m) in wild-type BMDMs before and after LPS priming. c, Fluorescent microscopy of EdU-labelled newly synthesized mtDNA in wild-type BMDMs before and after LPS priming. Scale bars, 5 μm. Images are representative of three independent experiments. d, Relative total mtDNA amounts in wild-type BMDMs transduced with Polg shRNA (shPolg#1 and shPolg#2) or control shRNA, before and after LPS priming. e, IL-1β (left) and TNF (right) release by shCtrl-or shPolg-transduced LPS-primed BMDMs treated with different inflammasome activators. f, Relative total mtDNA amounts in wild-type (WT), Myd88−/− and Trif−/− (Trif is also known as Ticam 1) BMDMs after LPS priming. Data in a, b, d–f are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test. NS, not significant.

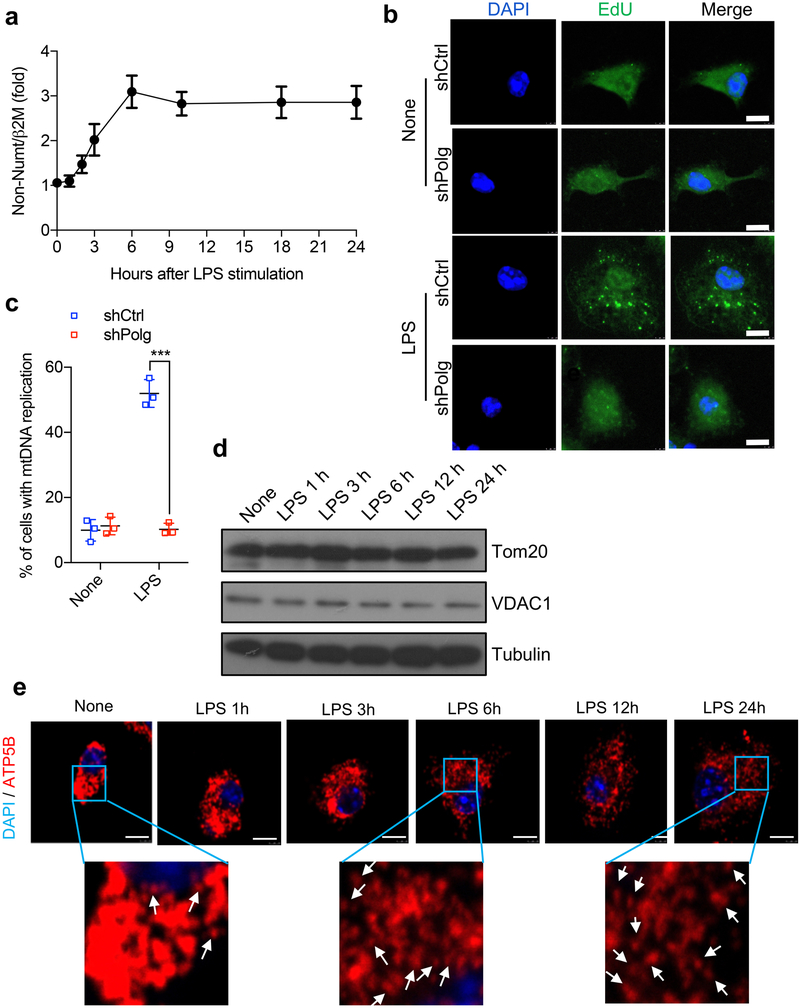

Because TFAM is required for mtDNA replication and maintenance16, and priming is needed for ox-mtDNA production, we looked for a link between priming and mtDNA metabolism. Notably, macrophage stimulation with LPS resulted in a rapid and robust increase in mtDNA copy number, peaking at around 6 h and remaining increased for at least 24 h after stimulation (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Increased mtDNA abundance correlated with enhanced incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) into mitochondrialike cytoplasmic organelles (Fig. 1c). Because ablation of DNA polymerase-γ (Polγ), the enzyme responsible for mtDNA replication17, prevented the LPS-induced increase in mtDNA abundance (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Figs. 2a, 3b, c), we reasoned that the increased mtDNA copy number in LPS-primed cells is due to new mtDNA synthesis and that the EdU-labelled organelles are indeed mitochondria, as their labelling was dependent on Polγ. More importantly, blockade of mtDNA synthesis inhibited NLRP3 activator- induced IL-1β production but had no effect on TNF synthesis (Fig. 1e). Although we cannot rule out a role for Polγ-mediated DNA repair, we reason that repair of patches of damaged mtDNA alone is unlikely to cause a two-to threefold increase in mtDNA copy number. Although mtDNA replication is often accompanied by increased mitochondrial mass, mitochondrial residential proteins were not increased (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Nonetheless, LPS treatment may have stimulated mitochondrial fission (Extended Data Fig. 3e). These results suggest that LPS-induced mtDNA replication is an important signalling event in activated macrophages rather than serving a general homeostatic function.

As LPS binds TLR4, which signals via MyD88 and TRIF18, we examined the involvement of these adaptors in LPS-induced mtDNA replication. Although MyD88 was responsible for the initial increase in synthesis of mtDNA, TRIF took over at later time points (Fig. 1f). Both MyD88 (early) and TRIF (late) contributed to NLRP3 activator- induced mtDNA oxidation and the formation of ASC specks with which new mtDNA was co-localized (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c).

IRF1 controls mtDNA replication and NLRP3 activation

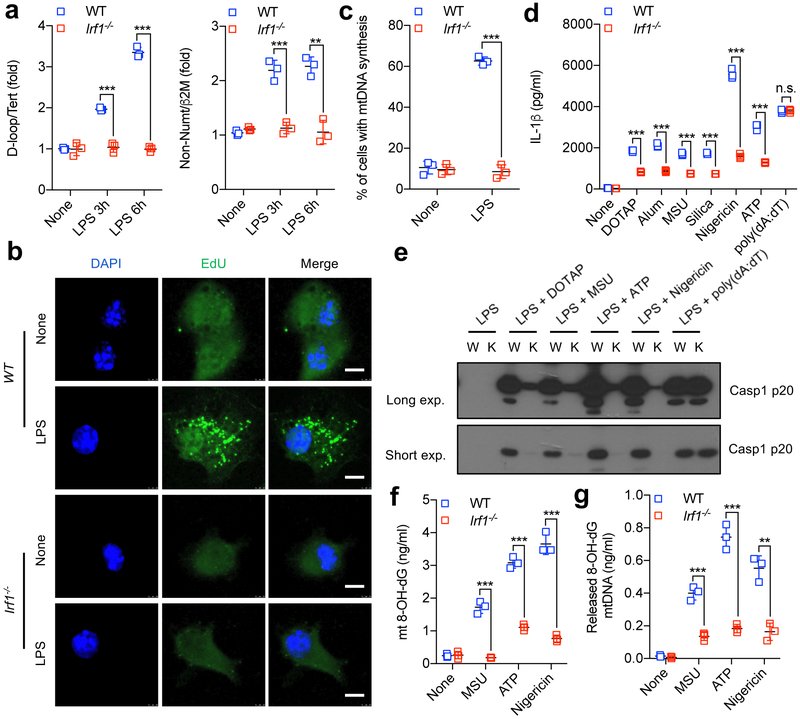

We searched for downstream targets of MyD88 and TRIF that could be involved in TLR-mediated stimulation of mtDNA synthesis and found that induction of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) followed similar kinetics to those of mtDNA synthesis and was similarly dependent on MyD88 at early time points and on TRIF at later stages (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). Importantly, IRF1 ablation blocked the induction of mtDNA synthesis (Fig. 2a–c) and Irf1−/− BMDMs showed a substantial reduction in NLRP3 activator-induced caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release, while retaining normal AIM2 inflammasome activation (Fig. 2d, e). The expression of pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 inflammasome components (including NEK719–21) and TNF secretion were also unaffected by IRF1 ablation, which also had no effect on NLRP3 activator- induced mitochondrial damage or mtROS production (Extended Data Fig. 5a–d). The IRF1 deficiency also did not affect caspase-11 mediated non-canonical inflammasome activation (Extended Data Fig. 5e, f). Owing to defective LPS-induced mtDNA replication, less ox-mtDNA was found in Irf1−/− BMDMs (both in mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions) after NLRP3 activator challenge (Fig. 2f, g). IRF1 probably controls ox-mtDNA production and NLRP3 inflammasome activation through its effect on mtDNA replication.

Fig. 2 ~. IRF1-dependent mtDNA synthesis, ox-mtDNA generation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Relative total mtDNA amounts in wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with LPS. b, Representative images showing EdU incorporation into mtDNA in wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs incubated without or with LPS for 6 h. Scale bars, 5 μm. c, Percentages of cells undergoing mtDNA synthesis, as determined in b (n = 3 different microscopic fields per group; original magnification, ×40). d, IL-1β release by LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1 BMDMs that were treated with different inflammasome activators. e, Immunoblot analysis of cleaved caspase-1 (Casp1 p20) in culture supernatants of wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were treated with LPS plus different inflammasome activators. Data are representative of three independent experiments. exp., exposure; K, knockout (Irf1−/−); W, wild type. f, g, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA within mitochondria (f) or in the cytosol (g) of LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs treated with NLRP3 activators. Data in a, d, f and g are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

CMPK2 controls mitochondrial DNA synthesis

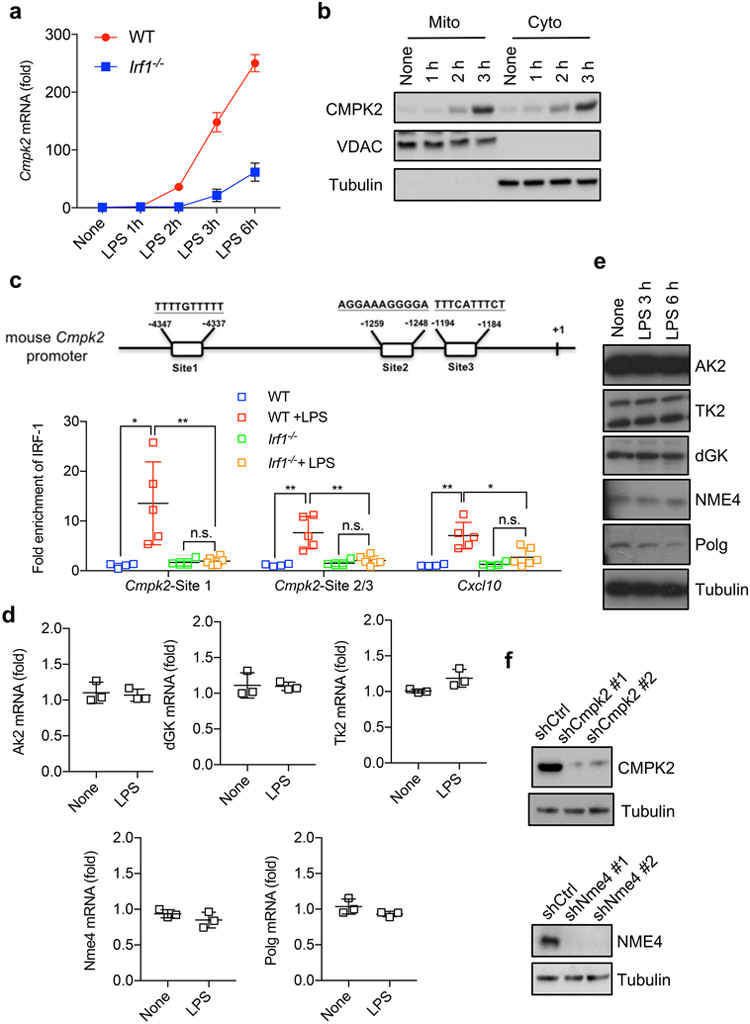

Because IRF1 is a transcription factor, we searched for an IRF1 target gene that may be involved in mtDNA replication, and found that the IRF1 transcriptome22 included a gene coding for the mitochondrial deoxyribonucleotide kinase UMP-CMPK2 (hereafter referred to as CMPK2)23. Of note, LPS priming resulted in strong induction of Cmpk2 mRNA and protein that was IRF1 dependent and showed similar dependence on MyD88 and TRIF as IRF1 did (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Figs. 4d–f and 6a). As expected, newly synthesized CMPK2 entered mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 6b). The 5′ control region of Cmpk2 contains three IRF1-binding sites, the functionality of which was confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (Extended Data Fig. 6c). CMPK2 is a mitochondrial nucleotide monophosphate kinase needed for salvage dNTP synthesis23. Notably, other nucleoside/nucleotide kinases in this pathway and Polγ were not LPS-inducible (Extended Data Fig. 6d, e), suggesting that CMPK2 is the rate-limiting enzyme that controls the supply of dNTP precursors for LPS-induced mtDNA synthesis. CMPK2 phosphorylates dCMP to dCDP, which is further converted into dCTP by the constitutive deoxyribonucleotide diphosphate kinase NME423,24.

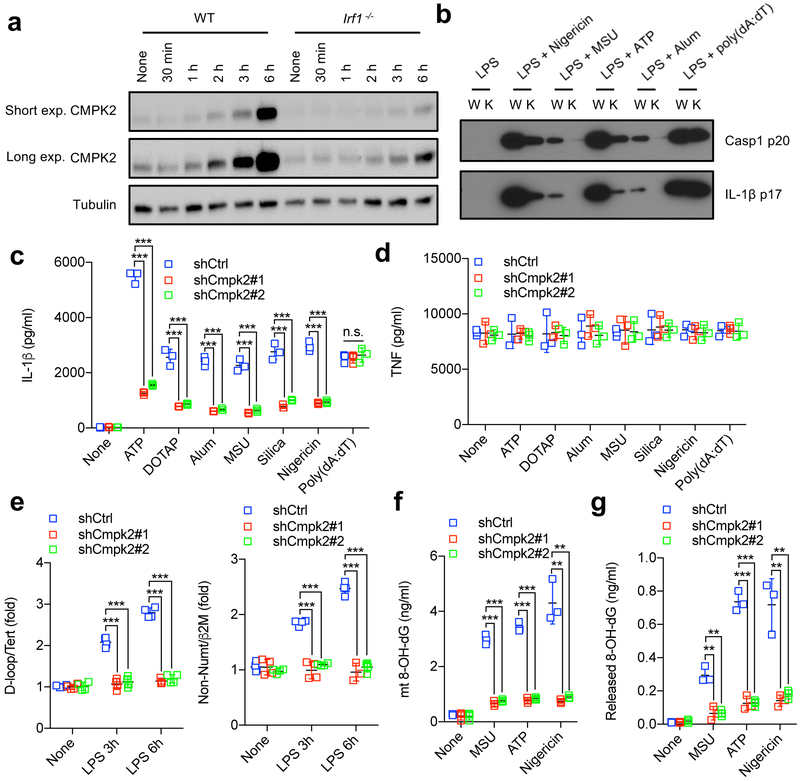

Fig. 3 ~. CMPK2 controls mtDNA synthesis, ox-mtDNA generation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Time-course analysis of CMPK2 accumulation in wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after LPS priming. b, Immunoblot analysis of cleaved caspase-1 (Casp1 p20) and mature IL-1β (p17) in the supernatants of shCtrl (wild-type, W) and shCmpk2 (knockdown, K) BMDMs that were stimulated with LPS plus the indicated inflammasome activators. Data in a and b represent three independent experiments. c, d, IL-1β (c) and TNF (d) secretion by LPS-primed BMDMs transduced with control shRNA or Cmpk2 shRNA (shCmpk2#1 and shCmpk2#2), and incubated with different inflammasome activators. e, Relative total mtDNA amounts in control and Cmpk2 shRNA BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. f, g, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA within mitochondria (f) or in the cytosol (g) of LPS-primed BMDMs transduced with control shRNA or Cmpk2 shRNA that were treated with different NLRP3 activators. Data in c–g are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates, except for n = 4 in e). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

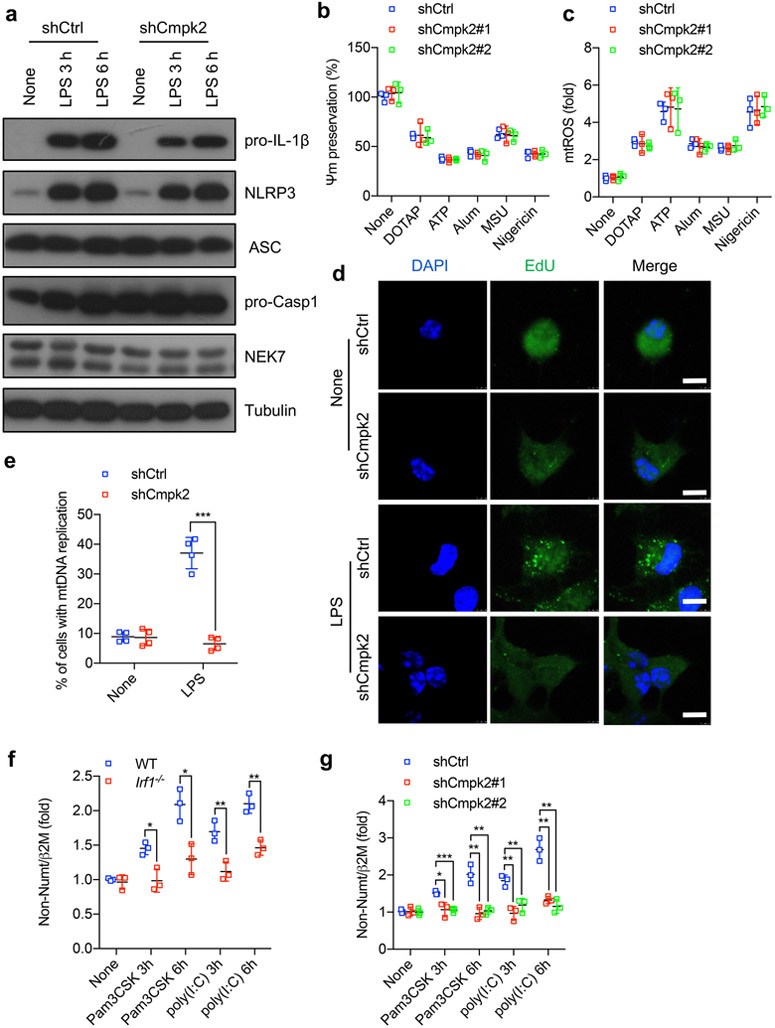

To validate the role of CMPK2 in LPS-induced mtDNA replication and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we knocked down Cmpk2 in wild-type BMDMs using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Extended Data Fig. 6f). CMPK2-deficient macrophages exhibited minimal NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 activation and IL-1β maturation relative to control CMPK2-sufficient cells, while retaining normal AIM2 responsiveness, TNF secretion and expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components as well as pro-IL-1β (Fig. 3b–d and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Although CMPK2 ablation did not affect mitochondrial damage or mtROS production after NLRP3 activator exposure (Extended Data Fig. 7b, c), CMPK2-deficient BMDMs did not upregulate mtDNA synthesis after LPS stimulation and barely produced ox-mtDNA (Fig. 3e–g and Extended Data Fig. 7d, e). Two other TLR ligands, the TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK and the TLR3 agonist polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid (poly(I:C)), which can prime inflammasome activation, also induced mtDNA replication via the IRF1 and CMPK2 pathway (Extended Data Fig. 7f, g), indicating that this pathway represents a common mechanism by which macrophages upregulate mtDNA abundance in response to TLR stimulation. NME4 ablation (Extended Data Fig. 6f) also blocked LPS-induced mtDNA synthesis, and reduced ox-mtDNA production as well as IL-1β secretion after NLRP3 inflammasome activation, without affecting AIM2 inflammasome activation or TNF production (Extended Data Fig. 8a–e). By contrast, increasing the cellular dNTP pool by the ablation of Samhd1, the dominant nucleotide triphosphate hydrolase25, the expression of which is induced by LPS in a TRIF-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 8f), enhanced new mtDNA synthesis and augmented IL-1β secretion after NLRP3 activator stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 8g–j). Enhanced IL-1β production in Samhd1−/− BMDMs remained dependent on mtDNA synthesis.

NLRP3 activation depends on CMPK2 catalytic activity

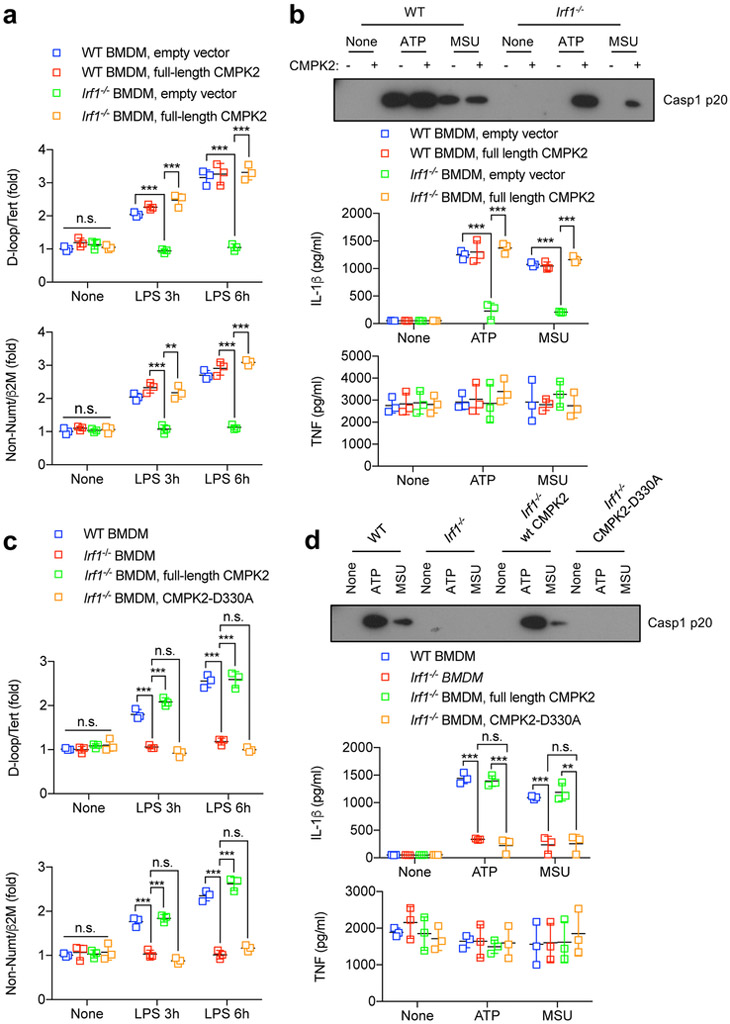

To confirm that CMPK2 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation by providing dCTP for mtDNA synthesis, we generated a catalytically inactive CMPK2 variant, CMPK2(D330A), by replacing the highly conserved aspartate (D) residue in its catalytic pocket23,26 with alanine (A). Expression of wild-type CMPK2 in Irf1−/− BMDMs restored LPS-stimulated mtDNA replication but did not enhance it in wild-type BMDMs (Fig. 4a). Although CMPK2 reconstitution did not alter the expression of pro-IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC and pro-caspase-1, and had no effect on mitochondrial damage or ROS induction by NLRP3 activators (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c), it restored NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 4b). By contrast, re-expression of CMPK2(D330A) did not restore LPS-induced mtDNA synthesis or NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 4c, d and Extended Data Fig. 9d). These results strongly support the notion that the induction of new mtDNA replication, which depends on CMPK2 catalytic activity, is required for the production of ox-mtDNA by mitochondria that have been damaged by exposure to NLRP3 activators, with ox-mtDNA being responsible for subsequent NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Fig. 4 ~. CMPK2 catalytic activity is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Relative total mtDNA amounts in LPS-treated wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs transduced with CMPK2-encoding or empty lentiviruses. b, Top, immunoblot analysis of Casp1 p20 in the supernatants of CMPK2 lentivirus-transduced LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with the indicated NLRP3 activators. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Bottom, IL-1β and TNF secretion by the above cells. c, Relative total mtDNA amounts in LPS-treated wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs transduced with either wild-type CMPK2-or CMPK2(D330A)-encoding lentiviruses. d, Top, immunoblot analysis of Casp1 p20 in supernatants of wild-type CMPK2-or CMPK2(D330A)-encoding lentiviruses transduced LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with NLRP3 activators. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Bottom, IL-1β and TNF secretion by the above cells. Data in a, b (bottom), c and d (bottom) are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

New mtDNA binds NLRP3 after mitochondrial damage

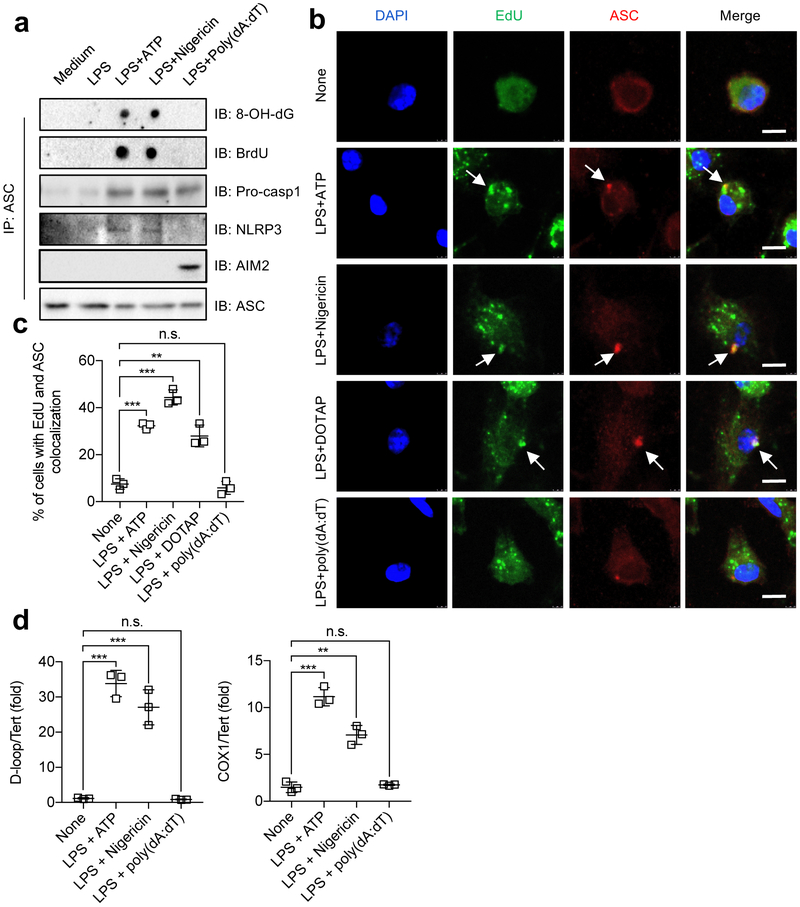

To verify the role of new mtDNA synthesis in NLRP3 signalling, we incubated BMDMs with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to label newly synthesized mtDNA, stimulated these cells with LPS and ATP or LPS and nigericin, and immunoprecipitated inflammasome complexes with ASC antibodies. The resulting immunocomplexes contained NLRP3, BrdU-labelled DNA, and 8-OH-dG (Fig. 5a). However, ASC immunocomplexes isolated from BMDMs that were stimulated with an AIM2 agonist did not contain NLRP3, BrdU-labelled DNA or 8-OH-dG (Fig. 5a), confirming specific interaction between newly synthesized and oxidized DNA and the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. To visualize this interaction, we examined the co-localization of ASC-containing inflammasome aggregates and EdU-labelled mtDNA before and after NLRP3 activator treatment. Remarkably, ATP, nigericin or 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) together with LPS induced co-localization of newly synthesized mtDNA with ASC specks, whereas the AIM2 agonist failed to do so, even in combination with LPS, which still induced EdU incorporation into cytoplasmic organelles (Fig. 5b, c). To confirm that NLRP3 inflammasome-associated DNA was of mitochondrial origin, we extracted DNA from ASC immunocomplexes and subjected it to PCR amplification. This resulted in detection of both D-loop and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) mitochondrial sequences in NLRP3-, but not AIM2-, inflammasome complexes (Fig. 5d). Notably, the fold-enrichment of D-loop mtDNA was higher than that of Cox1 (also known as mt-Co1) mtDNA (fig 5d), suggesting that mtDNA synthesis, which originates at the D-loop, is responsible for the generation of ox-mtDNA that binds NLRP3.

Fig. 5 ~. Newly synthesized mtDNA associates with the NLRP3 inflammasome complex.

a, Inflammasomes from BMDMs after indicated treatments were immunoprecipitated with ASC antibodies. The immunocomplexes were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane, UV-crosslinked and probed with antibodies to 8-OH-dG and BrdU, or separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to pro-Casp1, NLRP3, AIM2 and ASC. Data are representative of three independent experiments. b, Representative fluorescent microscopy images of EdU-labelled BMDMs that were co-stained for ASC, EdU and DAPI before and after stimulation with LPS plus different inflammasome activators. Arrows indicate co-localization of EdU and ASC signals. Scale bars, 5 μm. c, Percentages of cells with ASC and EdU co-localization as determined in b. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 different microscopic fields per group; original magnification, ×40). d, Relative D-loop (left) and Cox1 (right) mtDNA amounts in inflammasome complexes isolated as in a. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

IRF1 controls in vivo NLRP3 activation

Lastly, we established a requirement for IRF1 in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vivo. Intraperitoneal LPS injection is sufficient for the induction of an IL-1β- and NLRP3-dependent acute systemic inflammation that eventually leads to death7,27. Relative to wild-type mice, Irf1−/− mice exhibited markedly reduced IL-1β secretion but little change in TNF production and were largely resistant to LPS-induced death (Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). Importantly, Irf1−/− peritoneal macrophages isolated 3 h after LPS injection exhibited a lower mtDNA copy number than wild-type macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 10d). Irf1−/− mice were also refractory to alum-induced NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β production, and exhibited reduced neutrophil and monocyte infiltration relative to wild-type counterparts (Extended Data Fig. 10e–g).

Discussion

The NLRP3 inflammasome has a central role in numerous acute and chronic inflammatory and degenerative diseases1, but the mechanism that controls its activation is poorly understood. The difficulties stem from the fact that the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by structurally diverse and chemically unrelated entities, none of which binds NLRP3 itself28. NLRP3 inflammasome signalling depends on priming and activation, but whether and how priming affects inflammasome assembly and subsequent activation has remained elusive. Although mitochondrial damage and mtROS production were shown to be essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation9,12, they are induced by NLRP3 activators even in non-primed macrophages, where they do not result in inflammasome activation. We now show (Extended Data Fig. 10h) that priming and activation are coupled through the induction of new mtDNA synthesis, a hitherto unrecognized component of NLRP3 signalling. TLR4 engagement triggers MyD88/TRIF-dependent signalling that activates IRF1 to ultimately induce the expression of CMPK2, a mitochondrial nucleotide kinase with activity that is rate-limiting for de novo mtDNA synthesis. As a highly conserved enzyme, CMPK2 catalyses the synthesis of dCDP, which is further converted to dCTP by constitutively expressed NME4, thereby supplying an essential dNTP for mtDNA synthesis. Curiously, another TRIF-induced gene, Samhd1, encodes a dNTP hydrolase that curtails mtDNA synthesis and IL-1β production. Although new mtDNA synthesis is dispensable for mitochondrial damage and mtROS production, it is needed for the generation of what may be the ultimate NLRP3 ligand: ox-mtDNA. We demonstrate that newly replicated mtDNA co-precipitates and co-localizes with NLRP3 inflammasome complexes in macrophages incubated with LPS and NLRP3 activators. We postulate that newly synthesized mtDNA, which is yet to be packaged into a highly condensed nucleoid structure by TFAM16, is highly susceptible to oxidation and nuclease action, resulting in the production of ox-mtDNA fragments that are released via membrane pores that open after exposure to NLRP3 activators.

Mitochondrial involvement in NLRP3 inflammasome activation was first proposed by Tschopp and colleagues, but remained debatable12. Subsequently, Arditi and co-workers demonstrated that ox-mtDNA generated during apoptosis can bind NLRP313. We previously showed that autophagic elimination of mitochondria that were damaged after macrophage exposure to NLRP3 activators attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation11. Our current results show that long-term inhibition of mtDNA synthesis via TFAM ablation, or specific interference with TLR-induced mtDNA synthesis through ablation or inactivation of IRF1, CMPK2, NME4 or Polγ, prevents NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The latter, however, can be fully restored by the re-introduction of oxidized DNA into macrophages in the absence of any NLRP3 activators or apoptotic stimuli. Because any oxidized DNA regardless of its cellular source or sequence can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, we propose that NLRP3 is likely to recognize the presence of 8-OH-dG on the oxidized DNA molecule.

Lastly, we can only speculate why TLR engagement, which leads to MyD88/TRIF-dependent and IRF1-mediated CMPK2 induction, stimulates mtDNA synthesis. Perhaps mtDNA replication is needed for the maintenance of proper mitochondrial function to meet the energy and/or signalling demands of activated macrophages that are actively engaged in phagocytosis and other immune functions. Alternatively, mtROS production may result in mitochondrial damage and the elimination of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy. The induction of new mtDNA synthesis would allow macrophages to cope with TLR- stimulated ROS production29 that may otherwise result in mitochondrial depletion. A more intriguing possibility raised by the evolutionary relationships between mitochondria and intracellular parasitic bacteria is that CMPK2 induction may be an evolutionary relic that once helped such bacteria to survive and replicate within activated phagocytes23. Because CMPK2 catalytic activity is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, our results outline an entirely new approach for inhibiting NLRP3-dependent immunopathologies.

METHODS

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized except for the in vivo studies in which the age- and gender-matched mice were randomly allocated to different experimental groups based on their genotypes. Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment except for microscopic analysis of immunofluorescent staining results.

Mice.

C67BL/6, Irf1−/−, LysM-cre and Tfam−/− mice in the C57BL/6 background were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. LysM-cre mice were crossed with Tfamf/f mice to generate TfamΔMye mice. Myd88−/−, Trif−/− and Myd88−/−Trif−/− mice were previously described30. All mice were bred and maintained at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) and were treated in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents.

Ultrapure LPS (E. coli O111:B4) was from Invivogen. Silica and ATP were from Sigma-Aldrich. Imject Alum and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were from Pierce. MitoSOX, Click-iT EDU microplate kit and TSA kit (12) were from Life Technologies. Monosodium urate crystal (MSU) was from Enzo Life Science. TMRM was from AnaSpec Inc. (CA94555). DOTAP liposomes were made by Encapsula NanoSciences as described previously31. 90-bp fragments of nDNA and mtDNA with or without oxidation (8-OH-dGTP) or methylation (5-Me-dCTP) were from BioSynthesis. L929 cells (from ATCC) were authenticated before delivery to our laboratory, and were routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. Antibodies used for immunoblot analysis were: antimouse IL-1β (12426S, Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-mouse NLRP3 (AG-20B-0014-C100, Adipogen), anti-mouse AIM2 (sc-137967, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-mouse ASC (AG-25b-0006-C100, Adipogen), anti-mouse caspase-1 (AG-20B-0042-C100, Adipogen), anti-mouse deoxyguanosine kinase (ab38013, Abcam), anti-mouse thymidine kinase 2 (ab38302, Abcam), anti-mouse AK2 (ab166901, Abcam), anti-mouse NME4 (LS-C409886, LifeSpan BioSciences), anti-mouse TFAM (ab131607, Abcam), anti-mouse NEK7 (ab133514, Abcam), anti-mouse ATP5B (MAB3494, Millipore), rabbit anti-8-OH-dG (bs-1278R, Bioss), mouse anti-8-OH-dG (200-301-A99, Rockland), anti-BrdU (B8434, Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-tubulin (T5168, Sigma-Aldrich).

Macrophage culture and stimulation.

Primary BMDMs were generated by culturing mouse bone marrow cells in the presence of 20% (v/v) L929 conditional medium for 7 days as described32. BMDMs were seeded in 6-, 24-or 48-well plates overnight in FBS-free DMEM medium. On day 2, after priming with ultrapure LPS (200 ng ml−1) for 4 h, BMDMs (1 × 106 cells ml−1) were further stimulated with ATP (4 mM) or nigericin (10 μM) for 45 min unless otherwise indicated or DOTAP liposomes (100 μg ml−1), alum (500 μg ml−1), silica (600 μg ml−1) and MSU (600 μg ml−1) for 4 h. To activate the AIM2 inflammasome, macrophages were primed with LPS as above, followed by transfection of poly(dA-dT) (1 μg ml−1) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Similar approaches were used to transfect BMDMs with synthetic nuclear or mitochondrial DNA fragments. To activate caspase-11 non-canonical inflammasome, LPS was delivered into BMDMs using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Culture supernatants were collected 4 h after infection and IL-1β release was measured by ELISA. Supernatants and cell lysates were collected for ELISA and immunoblot analyses. Knockdown of Cmpk2, Nme4, Nlrp3 or Aim2 was done by lentiviral transduction of primary BMDMs as described previously11. Sequences of specific shRNAs (from Sigma shRNA Mission library) used in this study are as follows: shCmpk2#1 (5′-CCGGGTTTCGTCAGAAGGTGGAAATCTCGA GATTTCCACCTTCTGACGAAACTTTTT-3′); shCmpk2#2 (5′-CCG GTCTGCTTAACTCTGCGGTGTTCTCGAGAACACCGCAGAGTTAAGCAG ATTTTT-3′); shNme4#1 (5′-CCGGCAGTGTTCACATCAGCAGGAACTCGA GTTCCTGCTGATGTGAACACTGTTTTT-3′); shNme4#2 (5′-CCGG CCTCTGTCAACAAGAAGTCAACTCGAGTTGACTTCTTGTTGACAGAGG TTTTT-3′); shPolg#1 (5′-CCGGCGGACCTTATAATGATGTGAACTCGA GTTCACATCATTATAAGGTCCGTTTTTG-3′); shPolg#2 (CCGGCGATACT ATGAGCATGCACATCTCGAGATGTGCATGCTCATAGTATCGTTTTTG); shNlrp3#1 (5′-CCGGCCATACCTTCAGTCTTGTCTTCTCGAGAAGACA AGACTGAAGGTATGGTTTTTG-3′); shNlrp3#2 (5′-CCGGCCGGCCTTA CTTCAATCTGTTCTCGAGAACAGATTGAAGTAAGGCCGGTTTTTG-3′); sh Aim2# 1 (5′-CCGGGCTTTGTCTAAGGCTTGGGATCTCGAG ATCCCAAGCCTTAGACAAAGCTTTTTG-3′); shAim2#2 (5′-CCGGGCCATGT GGAACAATTGTGAACTCGAGTTCACAATTGTTCCACATGGCTTTTTG-3′).

RNA isolation and qPCR.

RNA was isolated from BMDMs and reverse transcribed, and qPCR was performed as previously described31. Primer sequences are as follows. Irf1 F: 5′-AATTCCAACCAAATCCCAGG-3′; Irf1 R: 5′-AGGCATCCTTGTTGATGTCC-3′; Cmpk2 F: 5′-GGCAATTATCTCGT GGCTTC-3’; Cmpk2 R: 5′-GTAGCTATGGCGTAGGTGGC-3′; dGK F: 5′-TCTGCATTGAAGGCAACATC-3′; dGK R: 5′-CTGCCACGCTGCT ATAGGTT-3′; Ak2 F: 5′-AGATTCCGAAGGGCATCC-3′; Ak2 R: 5′-GGC CAAATGACAGACACAAA-3′; Tk2 F: 5′-TCACCTGTACGGTTGATGGA-3′; Tk2 R: 5′-GAATCGCGTAGTCAACCTCG-3′; Nme4 F: 5′-GGACACACC GACTCAACAGA-3′; Nme4 R: 5′-CACAGAATCGCTAGCATGGA-3′; Polg F: 5′-ACGTGGAGGTCTGCTTGG-3′; Polg R: 5′-AGTAACGCT CTTCCACCAGC-3′; Hprt1 F: 5′-CTGGTGAAAAGGACCTCTCG-3′; Hprt1 R: 5′-TGAAGTACTCATTATAGTCAAGGGCA-3′.

ELISA.

Paired (capture and detection) antibodies and standard recombinant mouse IL-1β (from R&D Systems) and TNF (from eBioscience) were used to determine cytokine concentrations in cell culture supernatants and mouse sera according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of total mtDNA.

Macrophages were primed with LPS (200 ng ml−1) for the indicated time. Total DNA was isolated using Allprep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (catalogue 80204, Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instruction. mtDNA was quantified by qPCR using primers specific for the mitochondrial D-loop region or a specific region of mtDNA that is not inserted into nuclear DNA (non-NUMT)33. Nuclear DNA encoding Tert and B2m was used for normalization. Primer sequences are as follows: D-loop F: 5′-AATCTACCATCCTCCGTGAAACC-3′; D-loop R: 5′-TCAGTTTAGCTACCCCCAAGTTTAA-3′; Tert F: 5′-CTAGCT CATGTGTCAAGACCCTCTT-3′; Tert R: 5′-GCCAGCACGTTTCTCTCGTT-3′; B2m F: 5′-ATGGGAAGCCGAACATACTG-3′; B2m R: 5′-CAGTCTCAGTGGG GGTGAAT-3′; non-NUMT F: 5′-CTAGAAACCCCGAAACCAAA-3′, and non-NUMT R: 5′-CCAGCTATCACCAAGCTCGT-3′.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, wild-type and Irf1−/− primary BMDMs were treated with or without LPS, and then crosslinked with formaldehyde to generate DNA-protein cross-links. Cell lysates were digested with micrococcal nuclease to generate chromatin fragments and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with IRF-1 antibody or IgG isotype control. The immunoprecipitated chromatinized DNA was recovered and purified, followed by qPCR amplification with primers flanking the IRF-1 binding sites of the Cmpk2 promoter. In all experiments, the Cxcl10 promoter region that is known to include IRF-1 binding sites was used as a positive control.

Inflammasome immunoprecipitation.

Wild-type BMDMs were primed with LPS (200 ng ml−1) for 6 h in the presence of BrdU (10 μM) followed by treatment with ATP or nigericin for 60 min. The cells were washed twice with PBS and immunoprecipitation was performed using the Pierce Classic Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were collected as described above and lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Life Technologies), incubated with rabbit anti-ASC polyclonal antibody (AG-25b-0006-C100, Adipogen), rotated overnight at 4 °C. Magnetic beads were added and incubated with lysates on a rotator for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were then washed, bound fractions were eluted with non-reducing sample buffer and supplemented with dithiothreitol (DTT). For detection of BrdU and 8-OH-dG in the ASC immunoprecipitation products, the eluted samples were dot-blotted and UV cross-linked to a nitrocellulose membrane that was immunoblotted with BrdU monoclonal antibody (BU33; Sigma) or 8OH-dG BrdU monoclonal antibody (15A3; Rockland Immunochemicals). For the detection of NLRP3, AIM2, ASC and pro-caspase-1 in the ASC immunoprecipitation products, the eluted samples were heated to 95 °C for 5 min, the gel was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with antibodies against ASC (2EI-7, Millipore), NLRP3 (AG-20B-0014-C100, Adipogen), pro-casp1 (AG-20B-0042-C100, Adipogen) and AIM2 (sc-137967, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For the detection of mtDNA in the ASC immunoprecipitation products, DNA was extracted from eluted samples and qPCR was performed to amplify the D-loop region or the mitochondrial gene encoding cytochrome c oxidase 1 (Cox1). Nuclear DNA encoding Tert was used for normalization. Primer sequences are as follows: D-loop and Tert primer sequences are as described above; Cox1 F: 5′-GCCCCAGATATAGCATTCCC-3′, and Cox1 R: 5′-GTTCATCCTGTTCCTGCTCC-3′.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11836153001) and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, P5726). Protein concentrations were quantified using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, 23225). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then incubated with antibodies against IRF1, CMPK2, TFAM, NEK7, AK2, dGK, NME4, TK2, Polγ, NLRP3, ASC, α-tubulin, caspase-1 or IL-1β (as described above), followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies, and development with ECL.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential and mtROS.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) and mtROS were measured as previously described11 using TMRM and MitoSOX, respectively. In brief, BMDMs were put onto 6-well plates and primed with LPS (200 ng ml−1) followed by treatment with ATP or nigericin for 30 min or alum, silica, MSU or DOTAP liposomes for 3 h, after which the cells were washed twice with PBS. Then cells were detached and transferred into sterile 1.7-ml tubes for NLRP3 activator treatment. All the cell-staining procedures after NLRP3 activator stimulation were then performed in the tube. For Ψm measurement, BMDMs were loaded with 200 nM TMRM for 30 min and washed twice with 50 nM TMRM. For mtROS measurement, BMDM were loaded with 4 μM MitoSOX for 20 min and washed twice with PBS. After staining and washing, cells were resuspended in PBS and counted. Equal numbers of cells from different treatment groups were then plated onto 96-well plates for fluorescence reading to minimize the variation due to unequal cell numbers or differences in the cell attachment among treatment groups. Fluorescence intensity was determined using a FilterMax F5 multimode plate reader (Molecular Devices), and the data were normalized to LPS-primed but NLRP3 activator-untreated controls.

Cellular fractionation and quantification of cytosolic mtDNA.

Macrophages were first primed with LPS (200 ng ml−1) followed by treatment with ATP or nigericin for 60 min or MSU for 3 h. Cellular fractionation was then performed using a mitochondrial isolation kit for cultured cells (89874, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cytosolic mtDNA was measured as described10. In brief, DNA was isolated from 300 μl of the cytosolic fractions (after normalization via cytosolic protein concentrations) of NLRP3 activator-treated BMDMs and mtDNA levels were quantified by qPCR as described above. For the measurement of ox-mtDNA, mtDNA was first purified using Allprep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen) from the mitochondrial fraction of BMDMs as described above. The 8-OH-dG content of the mtDNA was then quantified using an 8-OHdG quantification kit (Cell Biolabs), as per the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy.

BMDMs were seeded at 0.2 × 106 cells per well in 8-well glass slides and rested overnight to allow proper attachment. To measure mtDNA replication, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (200 ng ml−1) for 3 or 6 h in the presence of 10 μM EdU. To examine co-localization of newly synthesized mtDNA with inflammasome complexes, LPS-primed BMDMs were further treated with ATP and nigericin or transfected with poly (dA-dT) using Lipofectamine 2000. The cells were washed twice with sterile PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with 1% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min, followed by three washes with PBS. EdU staining was performed using a Click-iT EdU Microplate Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,). In brief, BMDMs were postfixed in EdU fixative for 5 min, and equal volumes of the EdU reaction cocktail, which was made immediately before use, were added to each chamber and incubated for 25 min. The cocktail was then removed, and BMDMs were washed three times in 1% blocking solution from the Click-iT EdU Microplate Assay Kit. The Oregon Green azide signal was then amplified with a TSA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In brief, BMDMs were blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) plus 5% normal goat serum in PBS for 60 min, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated rabbit antibody against Oregon Green (from the EdU Microplate Assay Kit) diluted 1:300 in 1% BSA plus 5% goat serum in PBS overnight at 4 °C. For co-staining experiments, primary antibodies against ATP5B, ASC or 8-OH-dG (as described above) were included in the same solution with Oregon Green antibody. The next day, BMDMs were washed three times with PBS followed by incubation with Alexa-594 or -647 (from Life Technologies) secondary antibodies for 60 min. Then, BMDMs were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled tyramide at 1:100 in amplification buffer plus 0.0015% H2O2 for 10 min, and washed three times with PBS. DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining. Samples were imaged through a SP5 confocal microscope (Leica) 24 h after mounting.

CMPK2 reconstitution in Irf1−/− macrophages.

Wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs were transduced with virus stocks containing either a wild-type (pFLRcmv-Yept-puro-mCMPK2) or a catalytically inactive (pFLRcmv-Yept-puro-mCMPK2-D330A) CMPK2-encoding lentivirus. Virus-containing supernatants were filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore) and supplemented with polybrene (8 μg ml−1) before adding to cells. Four days after viral transduction, successfully transduced BMDMs were selected by puromycin followed by analysis of mtDNA replication and NLRP3 inflammasome activation as described above.

Septic shock and peritonitis models.

Septic shock was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 8–12-week-old gender-matched wild-type and Irf1−/− mice with LPS (E. coli O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich) at 50 mg per kg body weight. Mouse survival was monitored every 6 h after injection for a total of 72 h. In separate experiments, mice were treated with the same dose of LPS and immune sera were collected 3 h post injection. Serum IL-1β and TNF were measured by ELISA as described above. Peritonitis was induced by intraperitoneal injection of PBS or 1 mg alum (dissolved in 0.2 ml sterile PBS) into 8–12-week-old gender-matched wild-type and Irf1−/− mice. Mice from each genotype were allocated randomly into PBS or alum treatment groups. After 12 h, mice were euthanized and the peritoneal cavities were washed with 6 ml cold sterile PBS. Neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+ F4/80−) and monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−) present in the peritoneal lavage fluid were quantified by flow cytometry. For blocking Fc-mediated interactions, mouse cells were pre-incubated with 0.5–1 μg of purified anti-mouse CD16/CD32 per 100 μl. Isolated cells were stained with labelled antibodies in PBS with 2% FCS and 2 mM EDTA or cell staining buffer (Biolegend). Dead cells were excluded based on staining with Live/Dead fixable dye (FVD-eFluor780, eBioscience). Absolute numbers of immune cell subtypes in the peritoneum were calculated by multiplying total peritoneal cell numbers by percentages of immune cell subtypes amongst total cells. Cells were analysed on a Beckman Coulter Cyan ADP flow cytometer. Data were analysed using FlowJo 10.2 software (Treestar). Flow cytometry gating strategy was shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Antibodies specific for the following antigens were used: CD45 (m30-F11-V500); CD11b (mM1/70-eF450/eF660); MHCII (mM5/114.15.2-FITC/PE); Gr-1 (m1A8-Ly6G-PerCP-eF710); F4/80 (mBM8-PE/ FITC); and Ly6C (mHK1.4-eF450) (from eBioscience and Biolegend).

Statistics.

All data are mean ± s.d. or mean ± s.e.m. as indicated. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or log-rank test (for survival analysis). For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary.

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability.

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 ~. TFAM is required for ox-mtDNA generation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Inflammasome activator-induced changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) in non-or LPS-primed wild-type BMDMs were measured by TMRM fluorescence. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). b, Relative mtROS amounts were measured by MitoSOX fluorescence in non-or LPS-primed wild-type BMDMs after stimulation with different inflammasome activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). c, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA isolated from the mitochondrial fraction of non-or LPS-primed wild-type BMDMs that were treated with different inflammasome activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). d, Cytosolic release of mtDNA, determined by qPCR with primers specific for mtDNA (non-NUMT) and nDNA (B2m), in non-or LPS-primed wild-type BMDMs after treatment with different inflammasome activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 biological replicates). e, Immunoblot analysis of TFAM in Tfamff/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs. Results are typical of three independent experiments. f, Relative total mtDNA amounts in Tfamf/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs determined by qPCR with primers specific for mtDNA (D-loop, non-NUMT) and nDNA (Tert, B2m). Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). g, Relative mtROS amounts were measured by MitoSOX fluorescence in LPS-primed Tfamf/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs after stimulation with indicated NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). h, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA isolated from the mitochondrial fraction of LPS-primed Tfamff/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs that were stimulated with various NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). i, Immunoblot analysis of Casp1 p20 and mature IL-1β (p17) in culture supernatants of Tfamf/f (W) and TfamΔMye (K) BMDMs that were stimulated with LPS plus different inflammasome activators. Results are typical of three separate experiments. j, Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC and pro-Casp1 in the lysates of Tfamff/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs before and after LPS priming. Results are typical of three separate experiments. k, l, Amounts of IL-1β (k) and TNF (l) in culture supernatants of LPS-primed Tfamf/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs that were stimulated with various NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). m, Amounts of IL-1β in culture supernatants of LPS-primed Tfamf/f and TfamΔMye BMDMs that were stimulated with H2O2 in the absence and presence of nigericin. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 ~. ox-mtDNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome.

a, Immunoblot analysis of NLRP3, AIM2 and Polγ in shCtrl-or specific shRNA-transduced BMDMs. Data are typical of three separate experiments. b, Amounts of IL-1β in culture supernatants of LPS-primed TfamΔMye BMDMs that were transfected with mtDNA, methylated mtDNA, ox-mtDNA, and methylated ox-mtDNA. All mtDNAs were 90-bp long and of an identical sequence. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). c, Representative fluorescent microscopy images of wild-type BMDMs that were co-stained for 8-OH-dG, ASC and DAPI before and after stimulation with LPS plus the indicated inflammasome activators. Results are typical of three independent experiments. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 3 ~. LPS induces mtDNA replication.

a, Time-course analysis of total mtDNA amounts in wild-type BMDMs after LPS (200 ng ml−1) stimulation. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). Results are typical of three separate experiments. b, Representative fluorescent microscopy images of EdU-labelled shCtrl-or shPolg-transduced wild-type BMDMs that were stimulated with or without LPS (200 ng ml−1) for 6 h. Scale bars, 5 μm. Results are typical of three separate experiments. c, Percentages of cells with mtDNA replication as determined in b. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 different microscopic fields per group; original magnification, ×40). d, Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial resident proteins, TOM20 and VDAC, in wild-type BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Results are typical of three separate experiments. e, Representative fluorescent microscopy images of the mitochondrial resident protein ATP5B and DAPI staining in wild-type BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Results are typical of three independent experiments. Arrows indicate fragmented mitochondria. ***P < 0.001, two-sided unpaired t-test.

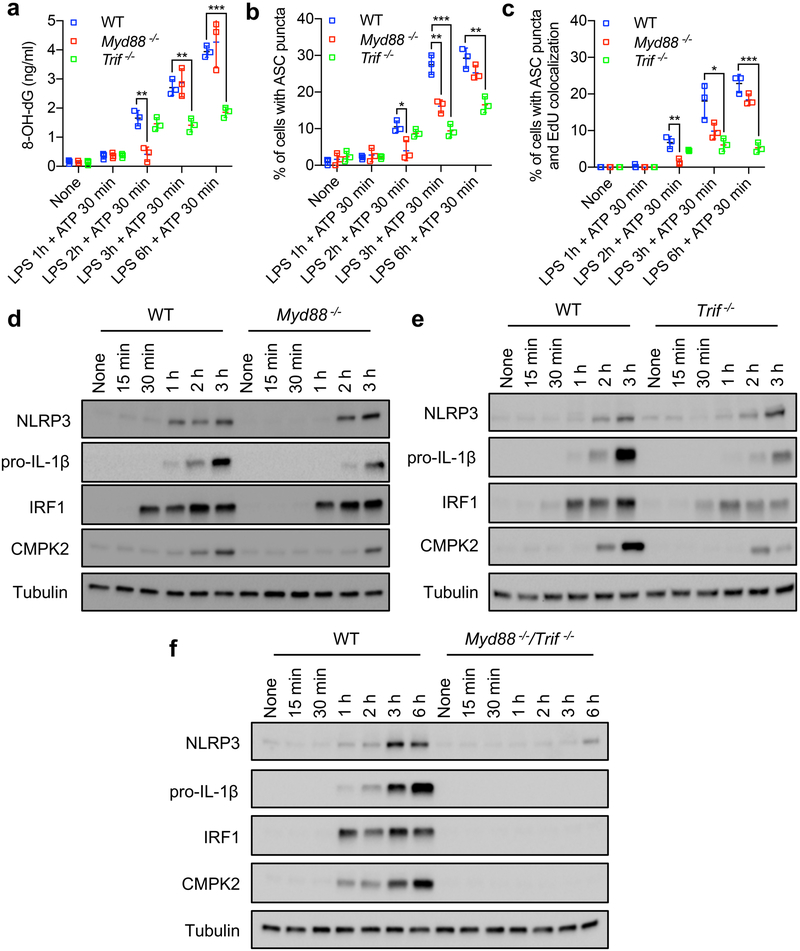

Extended Data Fig. 4 ~. MyD88 and TRIF mediate LPS-induced IRF1 and CMPK2 expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA isolated from mitochondrial fractions of wild-type, Myd88−/− and Trif−/− BMDMs that were primed with LPS for different durations followed by stimulation with ATP. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates per time point). b, c, Quantification of fluorescent microscopy images of ASC puncta (b) and ASC puncta positive for EdU (c) in wild-type, Myd88−/− and Trif−/− BMDMs that were primed with LPS for different durations, followed by ATP stimulation. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 different microscopic fields per group; original magnification, ×40). d–f, Immunoblot analysis of NLRP3, pro-IL-1β, IRF1 and CMPK2 in wild-type, Myd88−/− and Trif−/− BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Data are typical of three separate experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

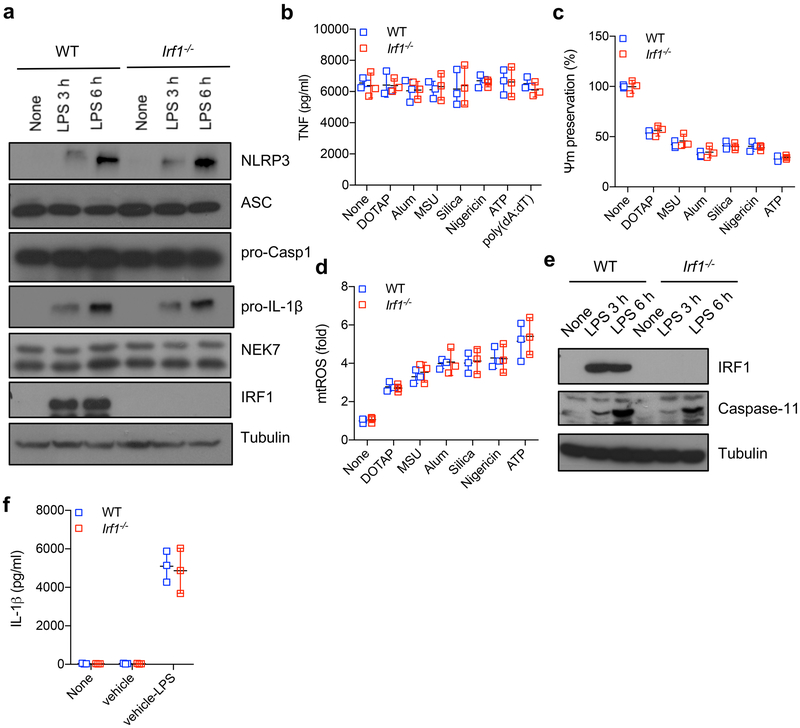

Extended Data Fig.5 ~. Effects of IRF1 on priming, mitochondrial damage and non-canonical inflammasome activation.

a, Immunoblot analysis of NLRP3, ASC, pro-caspase-1, pro-IL-1β, NEK7 and IRF1 in the lysates of wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Data are typical of three separate experiments. b, Amounts of TNF in culture supernatants of LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with the indicated inflammasome activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). c, Percentages of Ψm preservation were measured by TMRM fluorescence in LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with indicated NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). d, Relative amounts of mtROS were measured by MitoSOX fluorescence in LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with indicated NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). e, Immunoblot analysis of caspase-11 and IRF1 in lysates from wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Results are typical of three independent experiments. f, Amounts of IL-1β in culture supernatants of LPS-primed wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs that were further transfected with FuGENE-complexed LPS. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 6 ~. IRF1 mediates LPS-induced CMPK2 expression.

a, Relative amounts of Cmpk2 mRNA in wild-type and Irf1 −/− BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates per time point). b, Immunoblot analysis of CMPK2, VDAC and tubulin in mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions of wild-type BMDMs after LPS stimulation. Results are typical of three separate experiments. c, Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of IRF1 recruitment to the Cmpk2 promoter. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 biological replicates for wild-type and Irf1−/− groups; n = 5 and 6 biological replicates for wild-type + LPS and Irf1−/− + LPS groups, respectively). Cxcl10, a known IRF1-target gene, was included as a positive control. d, Relative mRNA amounts of dGK (also known as Dguok), Tk2, Ak2, Nme4 and Polg in wild-type BMDMs before and after 6 h LPS stimulation. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). e, Immunoblot analysis of the enzymes encoded by the genes in d in the lysates of wild-type BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Results are typical of three independent experiments. f, Immunoblot analysis of CMPK2 and NME4 in shCtrl-or specific shRNA-transduced BMDMs. Data are typical of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; two-sided unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 7 ~. CMPK2 deficiency does not affect inflammasome subunit expression nor NLRP3 activator-induced mitochondrial damage.

a, Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC, pro-Casp1 and NEK7 in the lysates of wild-type (shCtrl) and CMPK2-deficient (shCmpk2) BMDMs before and after LPS priming. Results are typical of three separate experiments. b, NLRP3 activator-induced changes in Ψm in LPS-primed shCtrl and shCmpk2 BMDMs were measured by TMRM fluorescence. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). c, Relative amounts of mtROS measured by MitoSOX fluorescence in LPS-primed shCtrl and shCmpk2 BMDMs after stimulation with the indicated NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). d, Representative fluorescent microscopy images of EdU-labelled wild-type BMDMs transduced with either shCtrl-or shCmpk2-encoding lentiviruses that were stimulated with or without LPS (200 ng ml−1) for 6 h. Scale bars, 5 μm. e, Percentages of cells with mtDNA replication as determined in d. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 different microscopic fields per group; original magnification, ×40). f, Relative amounts of total mtDNA in wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after treatments with the indicated TLR agonists. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). g, Relative amounts of total mtDNA in shCtrl-or shCmpk2-encoding lentivirus-transduced wild-type BMDMs before and after treatments with the indicated TLR agonists. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

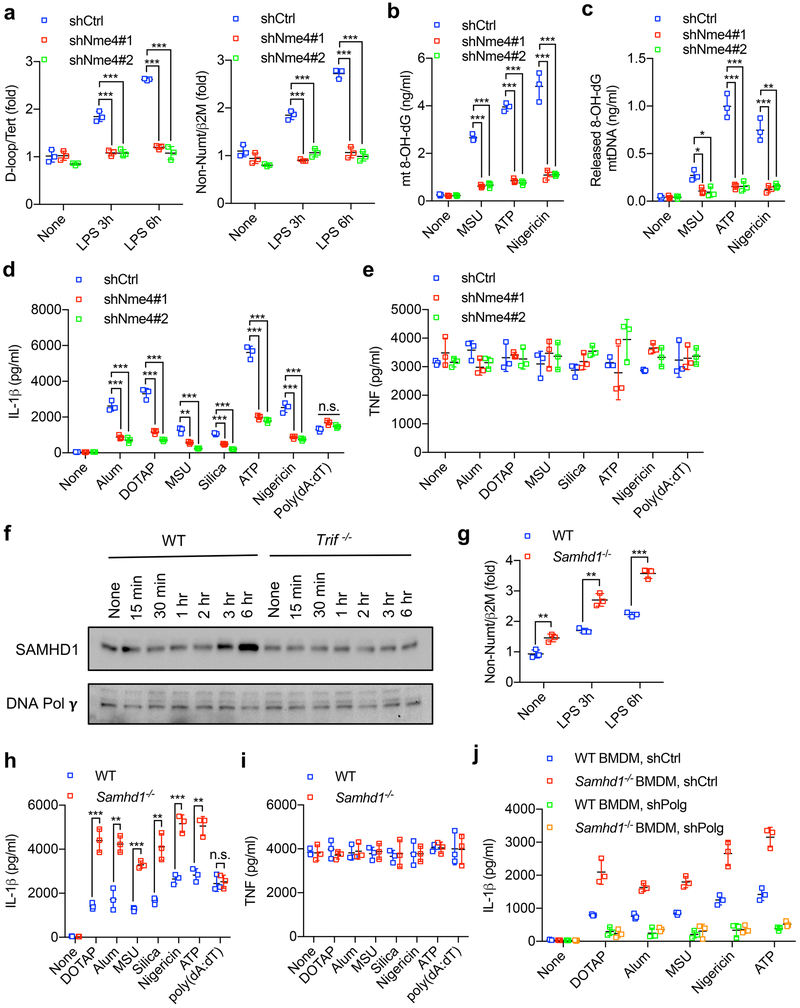

Extended Data Fig. 8 ~. dNTP availability controls LPS-induced mtDNA synthesis and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, Relative total mtDNA amounts in shCtrl and shNme4 BMDMs before and after LPS priming. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). b, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in mtDNA isolated from the mitochondrial fraction of LPS-primed shCtrl and shNme4 BMDMs that were stimulated with various NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). c, Amounts of 8-OH-dG in cytosolic mtDNA from LPS-primed shCtrl and shNme4 BMDMs that were stimulated with various NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). d, e, Amounts of IL-1β (d) and TNF (e) in supernatants of LPS-primed shCtrl and shNme4 BMDMs that were stimulated with various inflammasome activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). f, Immunoblot analysis of SAMHD1 and Polγ in wild-type and Trif−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with LPS for different durations as indicated. Results are typical of three independent experiments. g, Relative total mtDNA amounts in wild-type and Samhd1−/− BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). h, i, Amounts of IL-1β (h) and TNF (i) in the culture supernatants of LPS-primed wild-type and Samhd1−/− BMDMs that were stimulated with inflammasome activators as indicated. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). j, Amounts of NLRP3 activator-induced IL-1β in culture supernatants of LPS-primed wild-type and Samhd1−/− BMDMs with or without Polgexpression. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test.

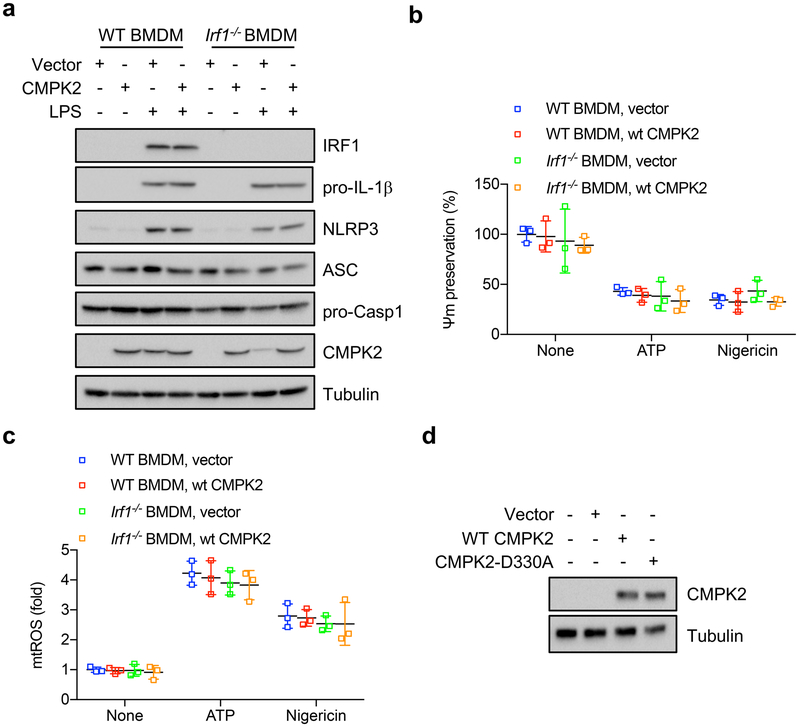

Extended Data Fig. 9 ~. CMPK2 expression restores NLRP3 inflammasome activation in IRF1-deficient macrophages.

a, Immunoblot analysis of IRF1, CMPK2, pro-IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC and pro-Casp1 in lysates of wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after transduction with a wild-type CMPK2-encoding lentivirus. Results are typical of three independent experiments. b, NLRP3 activator-induced changes in Ψm in LPS-primed CMPK2-transduced wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs were measured by TMRM fluorescence. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates) and analysed by two-sided unpaired t-test (not significant). c, Relative amounts of mtROS measured by MitoSOX fluorescence in LPS-primed control (vector)-or CMPK2-transduced wild-type and Irf1−/− BMDMs before and after stimulation with NLRP3 activators. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates) and analysed by two-sided unpaired t-test (not significant). d, Immunoblot analysis of CMPK2 in Irf1−/− BMDMs that were transduced with wild-type or mutant (CMPK2(D330A)) CMPK2-encoding lentiviruses. Results are typical of three separate experiments.

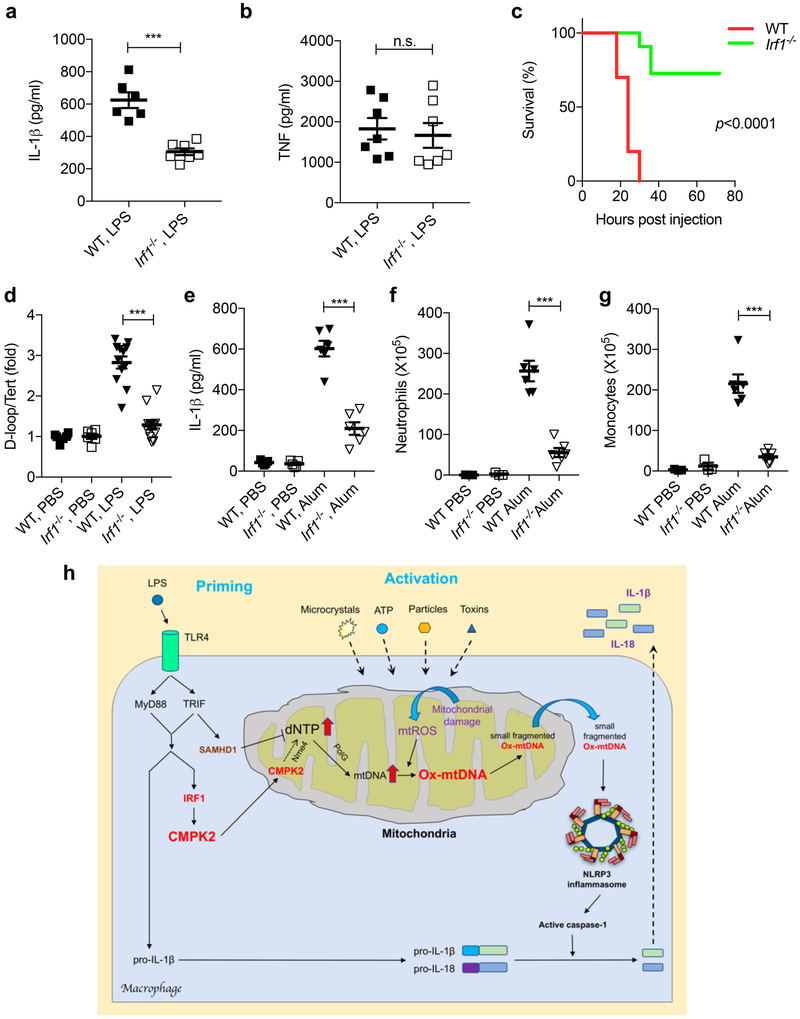

Extended Data Fig. 10 ~. IRF1 is required for in vivo mtDNA replication and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a, b, 12-week-old wild-type or Irf1−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with LPS (50 mg per kg of body weight) and their sera were collected 3 h later and analysed by ELISA for IL-1β (a) and TNF (b). Results are mean ± s.d. (n = 6 and 7 for WT and Irf1−/− mice, respectively). c, Survival of wild-type or Irf1−/− mice that were injected intraperitoneally with LPS (50 mg per kg body weight; n = 10 and 11 for WT and Irf1−/− mice, respectively). d, Relative amounts of total mtDNA in peritoneal infiltrates of wild-type or Irf1−/− mice before and after LPS (50 mg per kg body weight) injection. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 6 in PBS-treated groups; n = 12 in LPS-treated groups). e, Peritoneal IL-1β in wild-type or Irf1−/− mice 4 h after intraperitoneal injection of alum (1 mg) or PBS. Data are mean ± s.d. (n = 5 in PBS-treated groups; n = 6 in alum-treated groups). f, g, Alum-induced peritoneal infiltration of neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+F4/80−) (f) and monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−) (g) in wild-type and Irf1−/− mice 12 h after alum (1 mg) or PBS injection. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3 for PBS-treated groups and n = 6 for alum-treated groups). ***P < 0.001; two-sided unpaired t-test (a, b, d–g) and log-rank test (c). h, A working model to illustrate how TLR-mediated priming controls mtDNA replication and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Whereas IRF1 acts positively to induce the transcription of CMPK2, which supplies rate-limiting dCDP for mtDNA synthesis, TRIF-dependent signalling also acts negatively to limit dNTP supply through the induction of SAMHD1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank eBioscience, Cell Signaling Technologies, Santa Cruz Technologies, and Thermo Fisher for gifts of reagents, and N. Yan and J. Rehwinkel for SAMHD1-deficient murine bone marrow. Z.Z. was supported by Cancer Research Institute (CRI) Irvington Fellowship, Prevent Cancer Foundation Board of Directors Research Fund, and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Pinnacle Research Award; F.H. was supported by Eli Lilly LIFA program; S.S. was supported by fellowships from CRI-Irvington and Prostate Cancer Foundation; J.W. was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research fellowship (MFE-135425). Research was supported by NIH grants AI043477 and CA163798 to M.K., AA020172 and DK085252 to E.S., ES010337 to M.K. and E.S., DK109724 and P30DK063491 to A.L.H., DK099205, DK101737 and DK111866 to T.K., AA022614 to T.K. and M.K., Leukemia and Lymphoma Society SCOR grant 20132569 to T. Kipps and M.K., and the Alliance for Lupus Research grant 257214 and CART Foundation to M.K., who is an American Cancer Research Society Professor and holds the Ben and Wanda Hildyard Chair for Mitochondrial and Metabolic Diseases.

Footnotes

Competing interests The University of California San Diego is in the process of applying for a patent application (US Provisional Application Serial no. 62/690,175) covering the use of IRF1 and/or CMPK2 genetic/chemical inhibitors to treat NLRP3 inflammasome-associated diseases that lists Z.Z. and M.K. as inventors.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0372-z.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0372-z.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Online content

Any Methods, including any statements of data availability and Nature Research reporting summaries, along with any additional references and Source Data files, are available in the online version of the paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0372-z.

References

- 1.Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G & Tschopp J The inflammasome: an integrated view. Immunol. Rev 243, 136–151 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotas ME & Medzhitov R Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell 160, 816–827 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M & Clevers H Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 529, 307–315 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong Z, Sanchez-Lopez E & Karin M Autophagy, inflammation, and immunity: a troika governing cancer and its treatment. Cell 166, 288–298 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu A et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell 156, 1193–1206 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heneka MT, Kummer MP & Latz E Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol 14, 463–477 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamkanfi M & Dixit VM Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 28, 137–161 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroder K & Tschopp J The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latz E, Xiao TS & Stutz A Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 397–411 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakahira K et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol 12, 222–230 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong Z et al. NF-κB restricts inflammasome activation via elimination of damaged mitochondria. Cell 164, 896–910 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P & Tschopp J A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 469, 221–225 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimada K et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 36, 401–414 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X & Wang X Cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 73, 87–106 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamanaka RB et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote epidermal differentiation and hair follicle development. Sci. Signal 6, ra8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang D, Kim SH & Hamasaki N Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM): roles in maintenance of mtDNA and cellular functions. Mitochondrion 7, 39–44 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson G & Chinnery P F Mitochondrial DNA polymerase-gamma and human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet 15, R244–R252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai T & Akira S The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat, Immunol 11, 373–384 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Y, Zeng MY, Yang D, Motro B & Nüñez G NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature 530, 354–357 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi H et al. NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat. Immunol 17, 250–258 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid-Burgk JL et al. A genome-wide CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) screen identifies NEK7 as an essential component of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem 291, 103–109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jehl SP, Nogueira CV, Zhang X & Starnbach MN IFNγ inhibits the cytosolic replication of Shigella flexneri via the cytoplasmic RNA sensor RIG-I. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002809 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Johansson M & Karlsson A Human UMP-CMP kinase 2, a novel nucleoside monophosphate kinase localized in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem 283, 1563–1571 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milon L et al. The human nm23-H4 gene product is a mitochondrial nucleoside diphosphate kinase. J. Biol. Chem 275, 14264–14272 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballana E & Esté JA SAMHD1: at the crossroads of cell proliferation, immune responses, and virus restriction. Trends Microbiol 23, 680–692 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YL, Lin DW & Chang ZF Identification of a putative human mitochondrial thymidine monophosphate kinase associated with monocytic/ macrophage terminal differentiation. Genes Cells 13, 679–689 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinon F, Mayor A & Tschopp J The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu. Rev. Immunol 27, 229–265 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott EI & Sutterwala FS Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunol. Rev 265, 35–52 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West AP et al. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 472, 476–480 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto M et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science 301, 640–643 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong Z et al. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun 4, 1611 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornung V et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol 9, 847–856 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malik AN, Czajka A & Cunningham P Accurate quantification of mouse mitochondrial DNA without co-amplification of nuclear mitochondrial insertion sequences. Mitochondrion 29, 59–64 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.