Abstract

Introduction

The cigarette stick is an important communications tool as well as the object of consumption. We explored young adults’ responses to cigarettes designed to be dissuasive.

Methods

Data come from a cross-sectional online survey, conducted in September 2015, with 16- to 24-year-old smokers and nonsmokers (N = 997) in the United Kingdom. Participants were shown images of a standard cigarette (white cigarette paper with imitation cork filter), a standard cigarette displaying the warning “Smoking kills” on the cigarette paper, and an unattractively colored cigarette (green cigarette paper and filter). They were asked to rate each of the three cigarettes, shown individually, on eight perception items, and to rate the three cigarettes, shown together, on how likely they would be to try them. Ordering of the cigarettes and questions, with the exception of the question on trial, was randomized.

Results

The eight perception items were combined to form a composite measure of cigarette perceptions. For smokers and nonsmokers, the two dissuasive cigarettes (cigarette with warning, green cigarette) were rated significantly less favorably than the standard cigarette, and less likely to encourage trial. For cigarette perceptions, no significant interaction was detected between cigarette style and smoking status or susceptibility to smoke among never smokers. A significant interaction was found for likelihood of trying the cigarettes, with dissuasive cigarettes having a greater impact with smokers than nonsmokers.

Conclusions

This study suggests that dissuasive cigarettes may help to reduce the desirability of cigarettes.

Implications

The cigarette stick is the object of tobacco consumption, which is seen every time a cigarette is smoked. It is also an increasingly important promotional tool for tobacco companies. In this study, young adults rated two dissuasive cigarettes (a green colored cigarette and a cigarette displaying a health warning) more negatively than a standard cigarette, and considered them less likely to encourage product trial. Our findings suggest that it may be possible to reduce the desirability of cigarette sticks by altering their design, for example, with the addition of a warning or use of an unattractive color.

Introduction

While novel nicotine delivery systems such as electronic cigarettes and more traditional forms of nicotine delivery such as water pipes and cigarillos have grown in popularity this century, combustible cigarettes continue to dominate the global nicotine market.1 Approximately 5.6 trillion factory-made cigarettes (or about 800 cigarettes for every person on the planet) were sold in 2016, with cigarettes unsurprisingly responsible for most tobacco-related mortality and morbidity.2 This will continue to be the case for the foreseeable future given that cigarettes are predicted to remain the mostpopular means of consuming nicotine for some time.3 Consequently, implementing or strengthening existing measures known to reduce the appeal of cigarettes, and introducing novel means of doing so, must be a priority for public health.

The cigarette pack has received considerable attention from regulators, being considered the “final battleground.”4 It is a battle that many governments appear to be winning, given that Australia, France, and the United Kingdom (UK) have introduced plain (or standardized) packaging and several other countries are planning to do so, and pictorial health warnings are required on cigarette packs in over 100 countries.5 Consequently, tobacco companies have extended brand communication to the inside of the pack and to the cigarette itself.6 Tobacco companies are investing heavily in cigarette appearance (e.g., slim, colored and patterned designs) as well as speciality filters (e.g., adjustable filters, tube filters, and filters with one or more flavor-changing capsules) and tipping papers (e.g., heavy, tactile, and aromatic papers).6–10 To give one example of recent innovation, RJ Reynolds was granted a patent for an additional layer of detachable tipping paper that can be removed to allow the user a different sensory (e.g., visual, aromatic, or tactile) experience.11

Tobacco control research has failed to keep pace with these developments, and few studies have explored consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes available in most markets, including slimmer, colored, aromatic, and capsule cigarettes.12–15 Equally few studies have explored the possibility of using the cigarette to deter smoking, much in the way that the cigarette pack has been used. Aside from a number of recently published studies,16–21 research has overlooked the potential of using the cigarette stick as a dissuasive tool. Nevertheless, two promising concepts have emerged from these studies, which are the focus of this study: (1) cigarettes displaying a health warning and (2) cigarettes that are unattractively colored.

Moodie et al.19 conducted focus group research with young women smokers in 2012 to explore their perceptions of cigarettes bearing the warning “Smoking kills,” with the message displayed in one of four ways: (1) on the filter, (2) on the cigarette paper, displayed horizontally, (3) on one side of the cigarette paper, displayed vertically, and (4) on both sides of the cigarette paper, displayed vertically. The cigarette with the warning displayed vertically on both sides of the cigarette paper was considered most effective as it would have the greatest visibility. Participants commented that having a warning on all cigarettes would be unappealing, a constant reminder of the associated health risks, and off-putting, primarily because of the perceived discomfort of being observed by others smoking a cigarette displaying this message.19 In a study in 2014, marketing experts considered the same on-cigarette warning a powerful deterrent, thought to confront smokers, put off nonsmokers, signal to youth that it is neither cool nor intelligent to smoke, and prolong the health message.20 In another study, an in-home survey in 2014 with 11- to 16-year-olds who were shown an image of the on-cigarette warning, most thought that it would put people off starting (71%) and make people want to give up smoking (53%), with support for a warning on all cigarettes very high (85%).21

Hoek and Robertson17 conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with young women smokers in 2011 to explore perceptions of varied dissuasively coloured cigarettes. These cigarettes, particularly green and brown cigarettes, were perceived negatively, exposing smoking as dirty, reducing social acceptability and thought to make the smoking experience less satisfying. The dissuasively coloured sticks created an unsettling dissonance as participants struggled to reconcile these unappealing cues with the experience and identity they sought.17 Hoek et al18 conducted an online survey of 313 smokers in 2014 using a Best–Worst Choice experiment and rating task and explored dissuasive cigarettes that featured the warning “Smoking kills,” a graphic displaying minutes of life lost, or two aversive colors. Each dissuasively presented cigarette was less preferred and rated as less appealing than a standard cigarette.

This study extends previous research by exploring how young adult smokers and, for the first time, young adult nonsmokers perceive dissuasive cigarettes. With smoking prevalence high among 16- to 24-year-olds in the United Kingdom, and more than half of smokers starting to smoke regularly between the ages of 16 and 24,22 this is an important age group for public health interventions and a group of great interest to tobacco companies.23

Methods

Design and Sample

A web-based survey was conducted with 16- to 24-year-old self-defined smokers and nonsmokers (N = 1027), drawn from an online panel in the United Kingdom (Research Now), to explore perceptions of three cigarette sticks (a standard cigarette, a standard cigarette with the warning “Smoking kills” on the cigarette paper, and a green cigarette), Figure 1. An online approach was considered suitable as more than 99% of 16- to 24-year-olds in the United Kingdom are classed as recent internet users24 and online surveys have been commonly employed for research on cigarette packaging with younger people.25–27

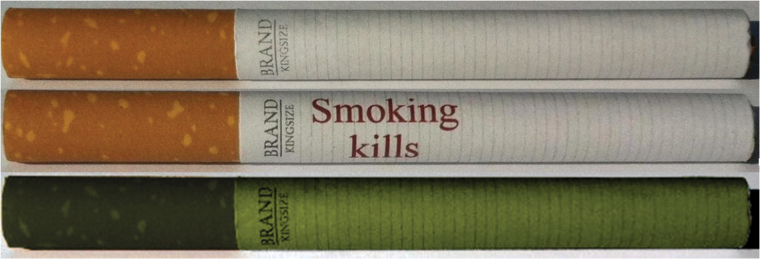

Figure 1.

Standard cigarette, cigarette with health warning “Smoking kills,” and green cigarette.

Online panels such as those maintained by Research Now are recruited from a wide range of sources and include details of members’ demographics and other characteristics that are used to profile the samples that are contacted for a particular project. For our study, Research Now provided a geographically representative sample of 16- to 24-year-olds in the United Kingdom. The target sample was stratified by gender and age, with two-thirds aged 20–24 years and equal numbers of males and females. This profile reflected smoking prevalence in the United Kingdom which, at the time of the study, was twice as high among 20- to 24-year-old males (29%) and females (29%) than it was among 16- to 19-year-old males (15%) and females (15%).22 The target sample of 500 nonsmokers and 500 smokers was driven by practical rather than statistical considerations; however, relevant subsamples are more than adequately powered, with >80% power to detect differences in median semantic differential scores of 0.5.

The achieved sample contained 49% smokers, with 67% 20- to 24-year-olds and 51% females. Participant characteristics (gender, age, smoking status, smoking susceptibility among never smokers, education, ethnicity, and geographic region) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (Age, Gender, Smoking Status, Susceptibility, Educational Attainment, Ethnicity, and Region)

| Smokers | Nonsmokers | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 231 (48%) | 255 (50%) | 486 (49%) |

| Female | 253 (52%) | 258 (50%) | 511 (51%) |

| Age group | |||

| 16–19 | 157 (32%) | 174 (34%) | 331 (33%) |

| 20–24 | 327 (68%) | 339 (66%) | 666 (67%) |

| Smoking status | |||

| I smoke every day | 272 (56%) | 272 (27%) | |

| I smoke, but not everyday | 212 (44%) | 212 (21%) | |

| I used to smoke, but not anymore | 109 (21%) | 109 (11%) | |

| I have never smoked | 404 (79%) | 404 (41%) | |

| Susceptibility (never smokers) | |||

| Nonsusceptible | 301 (59%) | 301 (30%) | |

| Susceptible | 101 (20%) | 101 (10%) | |

| Highest qualification | |||

| No formal qualification | 23 (5%) | 17 (3%) | 40 (4%) |

| O grade/standard grade/ equivalent | 102 (21%) | 88 (17%) | 190 (19%) |

| Vocational qualification | 49 (10%) | 24 (5%) | 73 (7%) |

| Higher/A level/equivalent | 189 (39%) | 223 (43%) | 412 (41%) |

| HNC/HND/equivalent | 35 (7%) | 29 (6%) | 64 (6%) |

| First degree/higher degree | 86 (18%) | 132 (26%) | 218 (22%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White British | 363 (75%) | 379 (74%) | 742 (74%) |

| Other | 115 (24%) | 124 (24%) | 239 (24%) |

| Not specified | 6 (1%) | 10 (2%) | 16 (2%) |

| Region | |||

| England | 428 (88%) | 451 (88%) | 879 (88%) |

| Scotland | 29 (6%) | 24 (5%) | 53 (5%) |

| Wales | 22 (5%) | 25 (5%) | 47 (5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 5 (1%) | 13 (3%) | 18 (2%) |

| Total | 484 (100%) | 513 (100%) | 997 (100%) |

Measures

General Information

Age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, and region within the United Kingdom were obtained.

Smoking Status and Susceptibility

Nonsmokers indicated that they had never smoked or used to smoke, with smokers indicating that they smoked daily or nondaily.

Never smokers were also categorized as susceptible or nonsusceptible, based on their response to three items asking about future smoking intentions: (1) At any time during the next 12 months, do you think you will smoke a cigarette? (Definitely not, Probably not, Probably will, Definitely will), (2) If a friend offered you a cigarette, would you smoke it? (Definitely not, Probably not, Probably would, Definitely would), and (3) Do you think you will be smoking cigarettes a year from now? (Definitely not, Probably not, Probably yes, Definitely yes). Nonsusceptible never smokers responded “Definitely not” to each question, while susceptible never smokers gave at least one response other than “Definitely not” to any question. These items were adapted from Pierce et al.28

Cigarette Perceptions

Eight items were used to assess perceptions of each cigarette on appeal, harm, strength, and taste, using seven-point semantic scales with anchors showing two extremes, for example, “Attractive–Unattractive,” “Not stylish–Stylish,” “Not nice to be seen–Nice to be seen with,” “Not appealing to people my age–Appealing to people my age,” “Looks harmful to health–Does not look harmful to health,” “Low in tar–High in tar,” “Strong taste–Light taste,” and “Harsh taste–Smooth taste.” Two of these items were reverse coded at the analysis stage so that a high score (7) consistently indicated a more favourable rating of the cigarette: “High in tar (1)–Low in tar (7)”, and “Strong taste (1)–Light taste (7)”.

Product Trial

The Juster Scale (an 11-point probability scale designed to estimate conditional behaviors) was used to estimate trial for each cigarette, with the question “If a friend offered you each of the cigarettes shown below, on a scale of 0 to 10 how likely would you be to try them?” with anchors “No chance/almost no chance” and “Certain/practically certain.”29

Procedure

The panel provider, Research Now30 sent an email invitation to selected panel members to participate in the survey, with a link provided to do so. Participants were shown an image of one of the three cigarettes (standard, with health warning, with green filter, and cigarette paper) and asked their perceptions of this cigarette. The process was repeated for each of the two remaining cigarettes, with the ordering of the three cigarettes and eight questions randomized. Participants were then shown the three cigarettes together and asked about perceived product trial for each. They received a very modest incentive for participation, as is common for online panels.

The panel provider (Research Now) adheres to the Market Research Society Code of Conduct and before answering any questions participants were given information on confidentiality, anonymity, and the right to withdraw at any time. They were also required to provide consent for this survey, even though they had already consented to being part of an online panel. Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Health Sciences at the University of Stirling.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 21). Of the 1027 surveys completed, 997 were retained for analyses after 30 cases were removed for being completed in less than the minimum completion time, which had been set before data collection commencing. The eight ordinal items designed to assess cigarette perceptions were summed to create a single score for each of the three cigarette styles (standard, warning, green). The internal consistency of the composite score was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.80). The composite measure ranged from 8 (for the most unfavorable rating of a cigarette) to 56 (for the most favorable rating of a cigarette).

Descriptive statistics were produced for the composite cigarette perceptions score and the product trial score. As the data were ordinal, differences in distributions of the outcome scores between the different cigarettes styles were assessed with the Wilcoxon signed rank test, a nonparametric procedure suited to paired data. The warning cigarette and the green cigarette were compared with the standard cigarette. To account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni Correction was applied to the critical p value, resulting in a lower value (p < .025) being required to reach significance.

Multivariable analysis, using generalized estimating equations (GEE) due to the correlated nature of the data within respondents, was conducted for two outcomes: cigarette perceptions and product trial. For the multivariable analysis, the outcome scores were dichotomized because there was unlikely to be a linear relationship between the multivariable distribution of the predictors and the outcome ordinal scales. That is, the effect of the predictor variables in changing a slightly favorable to a more favorable response would be different to the effect required to change a slightly favorable to a slightly unfavorable response. For this reason treating the ordinal scales as a continuous response in a regression model would be inappropriate. The scores were dichotomized to enable a comparison of those participants rating the cigarette sticks unfavorably (a score below the midpoint of 32) with those rating the cigarette stick as neutral or favorable (score of 32 or above) and those who indicated they would be likely to try the cigarette stick (score above the midpoint of 5) with those who did not (score of 5 or less). The dependent variables were therefore: unfavorable versus favorable or neutral ratings of the cigarette; and indication of being likely to try the cigarette versus not being likely to try the cigarette.

The within-subject variable was cigarette style. Independent variables were age group, education, ethnic group, smoking status, and gender. An interaction term was included for cigarette style by smoking status to assess whether any impacts from dissuasive cigarettes were consistent or whether they varied by smoking status. Similarly, interaction terms were included for cigarette style by education level and cigarette style by ethnicity. Interactions were not included for age or gender as none of the models indicated any main effects from age or gender. The GEE was specified with binomial distribution and logit link. We also specified an exchangeable within-subject correlation structure as this was most appropriate to capture the within-subject correlation due to individual response predisposition. Standard errors were calculated using the robust variance estimator. Adjusted odd ratios (AORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to assess the effects of cigarette style on the likelihood of favorable cigarette perceptions and likelihood of cigarette trial.

Results

Comparison of Ratings on the Three Cigarettes

Overall Perceptions (Composite Measure of the Eight Items)

Nonsmokers, on average, rated the standard cigarette unfavorably, with a median score at the lower end of the scale (median = 23.00, IQR = 15.00) (Table 2). Compared with the standard cigarette, nonsmokers rated the warning cigarette (median = 20.00, IQR = 15.50, p < .001) and green cigarette (median = 17.00, IQR = 16.00, p < .001) as more unfavorable.

Table 2.

Paired Comparison Tests for Ratings of the Standard Cigarette Compared With the Warning Cigarette and the Green Cigarette

| Nonsmokers (n = 513) | Smokers (n = 484) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | p Value* | Median | IQR | p Value* | |

| Overall perception of the cigarettes (composite variable from 8 items) | ||||||

| Unfavorable (8)/favorable (56) | ||||||

| Standard | 23.00 | 15.00 | 31.00 | 10.00 | ||

| v | ||||||

| Warninga | 20.00 | 15.50 | <0.001 a | 26.00 | 14.00 | <0.001 a |

| Greena | 17.00 | 16.00 | <0.001 a | 26.00 | 17.75 | <0.001 a |

| Trial: Low chance (0)/certainty (10) | ||||||

| Standard | 3.80 | 5.20 | 6.70 | 3.80 | ||

| v | ||||||

| Warning | 0.90 | 3.00 | <0.001 a | 3.80 | 5.10 | <0.001 a |

| Green | 0.80 | 3.15 | <0.001 a | 2.80 | 4.78 | <0.001 a |

IQR, interquartile range.

Wilcoxon signed rank test for significant differences, a Bonferroni correction has been applied to the critical p value, resulting in a p value <.025 being required for results to reach significance.

Compared with standard cigarette.

Smokers, on average, rated the standard cigarette as neither favorable nor unfavorable (median = 31.00, IQR = 10.00). Compared with the standard cigarette, smokers rated the warning cigarette (median = 26.00, IQR = 14.00, p < .001) and green cigarette (median = 26.00, IQR = 17.75, p < .001) as more unfavorable.

Trial

For nonsmokers, likelihood of trial was lower for the warning cigarette (median = 0.90, IQR = 3.00, p < .001) and the green cigarette (median = 0.80, IQR = 3.15, p < .001) than for the standard cigarette (median = 3.80, IQR = 5.20). For smokers, likelihood of trial was also lower for the warning cigarette (median = 3.80, IQR = 5.10, p < .001) and the green cigarette (median = 2.80, IQR = 4.78, p < .001) than for the standard cigarette (median = 6.70, IQR = 3.80) (Table 2).

Likelihood of Indicating Unfavorable Perceptions of the Cigarette Sticks

Unfavorable Perceptions (Composite Measure of the Eight Items), Controlling for Demographics and Smoking Status

The results of the GEE analysis indicate that, after controlling for demographic and smoking variables, participants were more likely to give the green cigarette (AOR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.44% to 2.87%, p < .001) an unfavorable score, compared with the standard cigarette, see Supplementary Table 1. The warning cigarette was also more likely than the standard cigarette to receive an unfavorable score (AOR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.70% to 3.24%, p < .001). An unfavorable perception of the standard cigarette was more likely among those with a higher education level (AOR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.12% to 2.02%, p = .007) and nonsmokers (AOR = 2.90, 95% CI = 2.20% to 3.83%, p < .001). There was no significant interaction between cigarette style and smoking status, indicating that the effect of the cigarette style was similar for smokers and nonsmokers. Similarly, the lack of interaction between cigarette style and education level and cigarette style and ethnicity indicates that the effect of dissuasive cigarettes did not differ within education or ethnicity.

Unfavorable Perceptions (Composite Measure of the Eight Items) Among Never-Smokers, Controlling for Demographics and Smoking Susceptibility

Among never-smokers, after controlling for demographic variables and smoking susceptibility, participants were more likely to give the warning cigarette (AOR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.01% to 3.73%, p = .047) an unfavorable score, compared with the standard cigarette (Supplementary Table 1). There was no significant difference in the likelihood of rating the green cigarette as unfavorable compared with the standard cigarette. An unfavorable perception of the standard cigarette was more likely among those with a higher education level (AOR=1.94, 95% CI = 1.10% to 3.42%, p = .022), while being susceptible to smoking (AOR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.27% to 0.80%, p = .006) and having ethnicity other than white British was associated with more favorable ratings (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.32% to 0.93%, p = 0.027). There was no significant interaction between cigarette style and smoking susceptibility, indicating that the effect of cigarette style was similar for susceptible and nonsusceptible never smokers. Similarly, there was no interaction between cigarette style and education level or cigarette style and ethnicity.

Likelihood of Trying the Cigarettes

Likelihood of Trying the Cigarettes, Controlling for Demographics and Smoking Status

Likelihood of trying the standard cigarette was lower among nonsmokers (AOR = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.05% to 0.09%, p < .001). There was a significant interaction between cigarette style and smoking status, indicating that the effect of the green cigarette (AOR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.45% to 4.04%, p = .001) and warning cigarette (AOR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.45% to 3.31%, p < .001) was greater for smokers than for nonsmokers. While there was no significant main effect of ethnicity, there was a significant interaction between cigarette style and ethnicity, indicating that the green cigarette was less effective at discouraging intended trial among participants who were not White British.

Likelihood of Trying the Cigarettes Among Never-Smokers, Controlling for Demographics and Smoking Susceptibility

Among never-smokers, after controlling for demographic variables and smoking susceptibility, the style of cigarette had no significant effect on the likelihood of trying the cigarette (Supplementary Table 2). Susceptible never smokers were more likely than unsusceptible never smokers to indicate that they would try the standard cigarette (AOR = 4.44, 95% CI = 1.90% to 10.35%, p = .001). There was no significant interaction between cigarette style and smoking susceptibility, or cigarette style and ethnicity, indicating that the effect of the cigarette style was similar within each of these groups. There was a significant interaction between cigarette style and education, indicating that more highly educated never smokers were less likely to indicate they would likely try the green cigarette (AOR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.06% to 0.77%, p = .019).

Discussion

We found that in comparison to a standard cigarette, two cigarettes designed to be dissuasive were considered significantly less favorably, and reduced the likelihood of product trial among both smokers and nonsmokers. The deterrent effect of the on-cigarette warning is consistent with past research with adolescents, smokers, and marketing experts.18–21 Marketing experts also suggested that cigarettes could be an unpleasant color, for example, green, as an alternative to the on-cigarette warning, given the importance of color for visual communication and the ability to elicit associations.20 The negative perceptions of the green cigarette in this study are consistent with this view and past research.17,18

While there were no age and gender differences in how the cigarettes were perceived, there were differences by smoking status, education, and ethnicity. The effect on trial of the dissuasive cigarettes was greater for smokers than for nonsmokers, which may be because nonsmokers are less likely to try any cigarette, irrespective of appearance, while for smokers the cigarette is the object of consumption. Those who were more highly educated were more likely to rate the standard cigarette unfavorably and, among never smokers, those who were more highly educated were less likely to indicate that they would try the green cigarette. This difference may reflect the lower smoking prevalence among those with higher educational attainment,22 with standard cigarettes viewed negatively and the use of an unattractive color further reducing appeal. The reasons for the differences found in terms of ethnicity are less apparent, however, given that smoking rates among different ethnic groups in the United Kingdom are often lower than for the general population, particularly among women.31 Participants who were not White British were more likely to indicate that they would try the green cigarette. With so few studies having explored perceptions of cigarette design, ethnicity seldom assessed within the plain packaging literature,32 and a paucity of research examining the differential effects of population-level tobacco control interventions by ethnicity,33 it is not clear what is driving this difference. Spence34 argues that although marketers try to establish universal or cultural specific color meanings, the perception of specific colors can vary by product, country, and population. It may be that a different color, such as brown or gray, which have been identified as two colors perceived as off-putting in the packaging literature,32,35 or a darker shade of green, may result in more negative perceptions among non-White British. Additional research with different ethnic groups, exploring their perceptions of cigarette design, may help explain the reasons underpinning these differences.

Like all studies, ours has some limitations. As the dissuasive cigarettes are not available in the marketplace, their novelty may have influenced respondents’ reactions to them.36 Further, we cannot tell how smokers and nonsmokers would respond when exposed to dissuasive sticks over a long period. For this, naturalistic research would be required, as has been employed in research exploring changes to the packaging.37,38 While younger adults are an important group for public health, and an online panel is an appropriate method of recruitment for this group, the focus on young adults and use of an online panel means that the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Future research could also build upon this study by exploring consumer perceptions of dissuasive cigarettes in comparison to standard and novel (e.g., slim or brightly colored) cigarettes, consistent with past research on packaging.39

While research exploring dissuasive cigarettes is in its infancy, our findings suggest that the cigarette stick, like the cigarette pack, is an important communications tool and that altering its appearance, for example, with the addition of a warning or unattractive color, can reduce its desirability. Although standardized packaging has been introduced in the United Kingdom (and Australia and France), this measure, by itself, can only partly reduce the appeal of cigarettes. British American Tobacco has argued that the idea that branded packaging can stimulate smoking by acting as a visual trigger, and that plain packaging will remove this effect, is ill-considered, because if this were to happen the plain pack, or indeed the cigarette itself, would simply take on the significance of the formerly branded pack.40 This suggests that tobacco companies view the cigarette stick as having an important role to play in smoking post-plain packaging. Consistent with this reasoning, tobacco industry journals suggest that marketing spend on the product is increasing and that plain packaging has heightened interest in novel filters.6,41 This has led to calls for more research monitoring how the cigarette stick is being used as a promotional tool,10 and how it could be used as a dissuasive tool.

Funding

Funding was provided by Cancer Research UK.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Eriksen MP, Mackay J, Schluger N, Gomeshtapeh FI, Drope J.. The Tobacco Atlas. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hedley D. Tobacco wars: a new hope—the changing future. Tob J Int. 2015;3:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yach D. Injecting greater urgency into global tobacco control. Tob Control. 2005;14:145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report. 5th ed.; 2016. www.tobaccolabels.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Cigarette-Package-Health-Warnings-International-Status-Report-English-CCS-Oct-2016.pdf .Accessed October 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tobacco Reporter. Tannpapier expands and innovates. Tob Reporter. 2016;2:56. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mapother J. Putting a shine on tipping. Tob J Int. 2012;2:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glogan T. Trend toward stiffer, heavier filters; CPF popularity grows. Tob J Int. 2015;3:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Moodie C, et al. Cigarette brands with flavour capsules in the filter: trends in use and brand perceptions among smokers in the USA, Mexico and Australia, 2012–2014. Tob Control. 2016;25:275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith KC, Washington C, Welding K, Kroart L, Osho A, Cohen JE. Cigarette stick as valuable communicative real estate: a content analysis of cigarettes from 14 low-income and middle-income countries. Tob Control. 2017;26:604–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tobacco Reporter. RJ Reynolds tipping paper. Tob Reporter. 2016;6:70. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borland R, Savvas S. Effects of cigarette stick design features on perceptions of characteristics of cigarettes. Tob Control. 2013;22:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ford A, Moodie C, MacKintosh AM, Hastings G. Adolescent perceptions of cigarette appearance. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Cummings KM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, Tworek C. Filter presence and tipping paper color influence consumer perceptions of cigarettes. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh A, Purves R. Are all cigarettes just the same? Female’s perceptions of slim, coloured, aromatized and capsule cigarettes. Health Educ Res. 2015;30:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hassan LM, Shiu E. No place to hide: two pilot studies assessing the effectiveness of adding a health warning to the cigarette stick. Tob Control. 2015;24:e3–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoek J, Robertson C. How do young adult female smokers interpret dissuasive cigarette sticks?J Social Market. 2015;5:21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoek J, Gendall P, Eckert C, Louviere J. Dissuasive cigarette sticks: the next step in standardised (‘plain’) packaging?Tob Control. 2016;15:699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moodie C, Purves R, McKell J, de Andrade M. Novel means of using cigarette packaging and cigarettes to communicate health risk and cessation messages: a qualitative study. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2015;13:333–344. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moodie C. Novel ways of using tobacco packaging to communicate health messages: interviews with packaging and marketing experts. Addict Res Theory. 2016;24:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moodie C, Mackintosh AM, Gallopel-Morvan K, Hastings G, Ford A. Adolescents’ perceptions of health warnings on cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;29:1232–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Statistics on Smoking England, 2016. Leeds: Health & Social Care Information Centre; 2016. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB20781/stat-smok-eng-2016-rep.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hendlin Y, Anderson SJ, Glantz SA. ‘Acceptable rebellion’: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell Camel cigarettes in the US. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Office for National Statistics. Internet Users in the UK: 2016. London: Office for National Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doxey J, Hammond D. Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. White CM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, Fong GT. The potential impact of plain packaging of cigarette products among Brazilian young women: an experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kotnowski K, Fong GT, Gallopel-Morvan K, Islam T, Hammond D. The impact of cigarette packaging design among young females in Canada: findings from a discrete choice experiment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1348–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Juster T. Consumer buying intentions and purchase probability: an experiment in survey design. J Am Stat Assoc. 1966;61:658–696. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Research Now. Research Now. www.researchnow.com/. Accessed October 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wardle H. Use of tobacco products. In: Sprotson K, Mindell J, ed. Volume 1: The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups. Leeds: The Information Centre; 2006:95–130. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L, et al. Plain Tobacco Packaging: A Systematic Review. Stirling: Centre for Tobacco Control Research, University of Stirling; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas S, Fayter D, Misso K, et al. Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking: systematic review. Tob Control. 2008;17(4):230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spence C. Multisensory packaging design: color, shape, textures, sound and smell. In: Burgess P, ed. Integrating the Packaging and Product Experience in Food and Beverages, 1st ed. A Road-Map to Consumer Satisfaction. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2016:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gallopel-Morvan K, Gabriel P, Gall-Ely ML, Rieunier S, Urien B. Plain packaging and public health: the case of tobacco. J Bus Res. 2013;66:133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schlackman W, Chittenden D. Packaging research. In: Worchester RM, Downham J, eds. Consumer Market Research Handbook. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1986:513–536. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moodie C, Mackintosh AM, Hastings G, Ford A. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of plain packaging: a pilot naturalistic study. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gallopel-Morvan K, Moodie C, Eker F, Beguinot E, Martinet Y. Perceptions of plain packaging among young adult roll-your-own smokers in France: a naturalistic approach. Tob Control. 2015;24(e1):e39–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ford A, Mackintosh AM, Moodie C, Richardson S, Hastings G. Cigarette pack design and adolescent smoking susceptibility: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. British American Tobacco. Consultation on the Introduction of Regulations for the Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products. Response of British American Tobacco UK Limited;2014. www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__9d9kcy.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO9MSFD3/$FILE/medMD9MWB4B.pdf?openelement. Accessed October 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glogan T. Plain pack prospects boost board sector. Tob J Int. 2016;1:94–98. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.