Abstract

Study Objectives:

Prior cross-sectional studies indicate that psychological factors (eg, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness) may explain the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation. Longitudinal studies are needed, however, to examine how these variables may relate to one another over time. Using data collected at three time points, this study aimed to evaluate various psychological factors as mediators of the longitudinal relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation.

Methods:

Young adults (n = 226) completed self-report measures of insomnia symptoms, suicidal ideation, and psychological factors (ie, disgust with self, others, and the world; perceived burdensomeness; thwarted belongingness; and loneliness) at baseline (T1), 1-month follow-up (T2), and 2-month follow-up (T3). Bias-corrected bootstrap mediation models were utilized to evaluate each T2 psychological factor as a mediator of the relationship between T1 insomnia symptoms and T3 suicidal ideation severity, controlling for the corresponding T1 psychological factor and T1 suicidal ideation severity.

Results:

Only T2 disgust with others and T2 disgust with the world significantly mediated the relationship between T1 insomnia symptoms and T3 suicidal ideation severity. When both mediators were included in the same model, only T2 disgust with the world emerged as a significant mediator.

Conclusions:

Findings indicate that disgust with others, and particularly disgust with the world, may explain the longitudinal relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation among young adults. These factors may serve as useful therapeutic targets in thwarting the trajectory from insomnia to suicidal ideation. Research is needed, however, to replicate these findings in higher risk samples.

Citation:

Hom MA, Stanley IH, Chu C, Sanabria MM, Christensen K, Albury EA, Rogers ML, Joiner TE. A longitudinal study of psychological factors as mediators of the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation among young adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(1):55–63.

Keywords: suicide, sleep, insomnia, psychological, mediation

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Prior studies have only utilized cross-sectional designs to evaluate psychological factors underlying the association between insomnia and suicidal ideation. This longitudinal study was designed to test various psychological factors as statistical mediators of the prospective relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation.

Study Impact: Our findings suggest that it may be clinically useful to target disgust with others and the world in order to thwart the trajectory from insomnia to suicidal ideation.

INTRODUCTION

A robust body of literature has identified insomnia—defined by the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)1 as “dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, with complaints of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep” (p. 363)—as both a correlate and predictor of elevated suicide risk. Specifically, across studies, insomnia has been associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and death by suicide.2 Relatively less is known, however, regarding the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk. Identification of these mechanisms is critical because they may inform our understanding of the development and maintenance of suicidal ideation and behaviors, as well as illuminate risk reduction strategies for individuals experiencing insomnia.

To this end, a recent systematic review3 sought to identify psychological factors that might explain the association between insomnia and suicide risk. Of the factors pinpointed in the review, those currently with the greatest empirical support are perceived burdensomeness (ie, beliefs that others would be better off if one were dead) and thwarted belongingness (ie, lack of meaningful social connection), two constructs posited by the interpersonal theory of suicide as necessary for the emergence of suicidal ideation.4–6 For example, Chu et al.7 utilized bootstrap mediation analyses to demonstrate that thwarted belongingness significantly accounted for the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation in a sample of South Korean young adults. This same pattern of findings was replicated with bootstrap mediation analyses conducted in three samples of military service members and veterans8 and distinct samples of United States young adults, psychiatric outpatients, firefighters, and primary care patients.9 Furthermore, multi-study investigations conducted by Nadorff et al.10 and Golding et al.11 both found, in at least one of their samples, that the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk was no longer statistically significant after controlling for interpersonal theory variables. These results provide additional support for the notion that interpersonal theory of suicide constructs explain the insomnia-suicidality association. As Littlewood et al.3 explicate, insomnia may cause individuals to feel socially isolated and lead to disengagement from social activities, elevating both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, which, in turn, increase suicide risk (see also Chu et al.7).

Though findings from these studies are promising and consistent with a theoretical framework, they are limited in their interpretability. Each study relied upon cross-sectional data, with the exception of the primary care sample in Chu et al.,9 which still only examined data collected at two time points. To identify factors that account for the prospective relationship between two constructs, a longitudinal study design with at least three data collection points is essential. In so doing, the temporal relationship between the independent variable, mediators, and dependent variable can be evaluated and baseline clinical severity can be taken into account. Cross-sectional mediation analyses can result in biased estimates and fail to account for the effect of time on variables.12,13 Therefore, longitudinal studies with multiple assessment points are needed for a rigorous evaluation of the temporal relationship between insomnia, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide risk. Such longitudinal studies may also benefit from the evaluation of other plausible—yet, by comparison, relatively understudied—mediators of the prospective relationship between insomnia and suicide risk.

Another construct that has been posited to explain the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk is loneliness.3 Loneliness—defined as the painful perception and/or experience that one does not belong or is isolated from other individuals14—is considered to be related to yet distinct from thwarted belongingness (ie, lack of meaningful social connection).15 Insomnia may contribute to loneliness because individuals with insomnia often spend many hours awake when others are asleep, a distressing experience that may play a role in the development of suicidal ideation.16 Though aforementioned studies7–10 have suggested that loneliness may explain the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk, these studies utilized thwarted belongingness as a proxy for loneliness. Notably, the authors of each of these investigations recommended that future studies include a validated measure of loneliness when examining factors underlying the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk. Thus, there is rationale for an investigation of loneliness, specifically, as a mediator of the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk.

Negative cognitive appraisals of the self and others represent another potential explanatory factor in the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk. Insomnia's negative impact on cognitive functioning17 and emotion regulation18 may lead to more negative views of oneself and others, resulting in the emergence and maintenance of suicidal ideation.3 In considering prior conceptual and empirical work, one type of negative cognitive appraisal that may account for the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk is disgust with life—that is, “maladaptive thoughts that life—one's self, others, the world, and existence in general—is repulsive” (p. 236).19 Chu et al.19 posit in their conceptual review that disgust with life may be associated with physiological manifestations of withdrawal (eg, insomnia) and suicide-related cognitions. A sleepless world is one with no rest or solace, and consequently, people may find themselves repelled by it. Additionally, research suggests that disgust with oneself (ie, self-alienation) and disgust with others and the world (ie, alienation from others), alongside insomnia, may be key features of acute suicidal affective states.20–22 Thus, disgust with life may develop in the context of more severe insomnia and lead to or exacerbate suicidal ideation. Research is needed, though, to test this conjecture.

The Present Study

Taken together, it is evident that longitudinal studies with multiple data collection waves are needed to identify psychological factors that mediate the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk. Utilizing data collected at three time points across 2 months, this study aimed to evaluate various psychological factors (ie, disgust with self, others, and the world; perceived burdensomeness; thwarted belongingness; and loneliness) as mediators of the (1) cross-sectional and (2) longitudinal relationship between insomnia symptom severity and suicidal ideation severity in a sample of young adults. Although, as noted, longitudinal studies are needed to identify mediators of this relationship, we also conducted cross-sectional analyses to allow for comparisons with previous cross-sectional studies and this study's longitudinal findings. A 2-month study length was used to address gaps of prior studies, which have largely evaluated predictors of suicidal ideation over relatively long periods of time (eg, years; see Franklin et al.23 for review). Based on prior empirical and theoretical work, we hypothesized that each psychological factor would significantly mediate the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation both in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses.

Given the propositions of the interpersonal theory of suicide,4,5 we also conducted exploratory moderated mediation analyses to test whether (1) perceived burdensomeness moderated the mediating effects of thwarted belongingness and (2) thwarted belongingness moderated the mediating effects of perceived burdensomeness both in cross-sectional and longitudinal mediation models. We expected that each of these moderated mediation analyses would yield significant results, with significant mediating effects observed only at high levels of each moderator, in line with the predictions of the interpersonal theory of suicide.4,5

METHODS

Participants

A sample of 226 undergraduate students participated in this study. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 47 years (mean = 19.42, standard deviation = 2.23). The majority were female (n = 201, 89%), and 74% (n = 167) self-identified as white/Caucasian, 6.6% (n = 15) as black/African American, 13.7% (n = 31) as Hispanic or Latino/a, 3.5% (n = 8) as Asian/Pacific Islander, and 2.2% (n = 5) as Other race/ethnicity. Regarding education level, 41% (n = 93) of participants were in their first year of undergraduate studies, 24.8% (n = 56) second year, 19.0% (n = 43) third year, 13.3% (n = 30) fourth year, and 1.7% (n = 4) fifth year or more. Participants were recruited from the Department of Psychology Human Subjects Pool at a large public university in the Southeastern United States. Undergraduates aged 18 years or older were eligible to participate in this study. The use of an undergraduate sample is highly relevant because sleep disturbances are overrepresented in this population,24 and suicide is a leading cause of death among young adults.25 Also, understanding factors that contribute to suicidal ideation among young adults is important because the first onset of suicidality in college is a particularly concerning signal of suicide risk.26

Measures

Demographics and Psychiatric History Overview

A self-report measure was used to assess demographic characteristics and lifetime history of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts.

Depressive Symptom Inventory—Suicidality Subscale

The Depressive Symptom Inventory—Suicidality Subscale (DSI-SS)27 is a four-item self-report measure designed to assess suicidal ideation severity in the past 2 weeks. Individuals rate the frequency and controllability of their suicidal ideation, as well as severity of suicide plans and impulses, using a four-item Likert-type scale. Item scores are summed, with total scores ranging from 0–12 and higher scores indicating a greater severity of suicidal ideation. DSI-SS total scores ≥ 3 are considered clinically significant.27 The DSI-SS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties among young adults,27 and in this study, its internal consistency ranged from good to excellent across time points (αs = .84–.94).

Disgust With Life Scale

The Disgust With Life Scale (DWLS)28 is a 24-item self-report measure designed to assess various facets of disgust with life. This measure consists of three subscales, each composed of 8 items, assessing: (1) disgust with self (eg, “I am repulsed with the way I behave”); (2) disgust with others (eg, “Other people repulse me”); and (3) disgust with the world (eg, “Society makes me sick”). Participants rate the extent to which each item accurately characterizes themselves on a 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) scale. Items within each subscale are summed to yield total scores ranging from 0 to 32; higher total scores signal greater levels of disgust within that respective domain. Clinical cutoffs have not yet been established for the DWLS. The DWLS has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties.28 In the current study, the DWLS subscales demonstrated acceptable to excellent internal consistency across time points (DWLS disgust with self: αs = .91–.94; DWLS disgust with others: αs = .73–.81; and DWLS disgust with the world: αs = .93–.95).

Insomnia Severity Index

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)29 is a seven-item self-report measure of insomnia symptom severity in the past 2 weeks. Participants are asked to rate the severity of various sleep complaints and the degree of distress and impairment associated with their insomnia symptoms. Respondents rate each item on a 0 to 4 scale, and item scores are summed to yield total scores ranging from 0 to 28, with higher scores signaling more severe insomnia symptoms. ISI total scores ≥ 10 are considered clinically signiciant.29 The ISI has demonstrated good internal consistency and convergent validity across populations.29,30 The ISI demonstrated good internal consistency at baseline—the only ISI assessment used in this study (α = .88).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ)15 is a 15-item self-report measure designed to assess perceived burdensomeness (six items) and thwarted belongingness (nine items). Respondents rate the degree to which each item has been true for them “recently” on a 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me) scale. Items are reverse-coded as appropriate. Then, items are summed such that higher total scores indicate higher levels of perceived burdensomeness (range: 6 to 42) and thwarted belongingness (range: 9 to 63). No empirically established clinical cutoffs exist for the INQ. The INQ has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in prior studies,15 and in this study, both INQ subscales demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency across time points (INQ perceived burdensomeness: αs = .89–.91; INQ thwarted belongingness: both αs = .92).

UCLA Loneliness Scale—Version 3

The UCLA Loneliness Scale—Version 3 (UCLA-3)31 is a 20-item self-report measure of loneliness. Participants rate how often each item is “descriptive of [them]” on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Item scores are summed to yield a total score ranging from 20 to 80; higher scores indicate greater loneliness. There are no empirically established cut points for the UCLA-3. The UCLA-3 has demonstrated good reliability and validity in prior studies.31 In this study, the UCLA-3 demonstrated excellent internal consistency across time points (αs = .95).

Procedures

Individuals who signed up for the study via the University's Department of Psychology Human Subjects Pool were emailed a link to review a web-based consent form on Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. Participants were required to correctly answer a series of comprehension questions based on the consent form to enroll in the study. Enrolled participants then completed the same battery of self-report surveys at three time points spaced across 2 months: baseline (T1), 1-month follow-up (T2), and 2-month follow-up (T3). All self-report surveys were administered via Qualtrics. Upon completion of each assessment battery, participants were provided with information regarding local and national mental health resources (eg, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline [1-800-273-TALK]). At any assessment point, if a participant reported a nonzero level of current suicidal intent on a risk screening question (“What is your current intent to make a suicide attempt in the near future from 0 to 10, with 0 being none at all and 10 being a very strong intention?”), they were contacted via phone by a study clinician for a more detailed suicide risk assessment conducted using the Decision Tree Framework.32 Participants were compensated with research credit for a psychology course in which they were enrolled. The University's Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

A total of 286 participants completed the T1 survey battery, and 226 (79%) completed T2 and T3 survey batteries within the required window of time (ie, within three days of the 30-day follow-up deadline). There were no significant demographic differences between those who did and did not complete the study, except for sex—a greater proportion of males dropped out (n = 15, 37.5%) than females (n = 45, 18.3%; χ2 = 7.66, P = .006). Those who dropped out also had sig -nificantly higher scores on all T1 self-report measures as compared to those included (ie, greater DWLS disgust with self, DWLS disgust with others, DWLS disgust with the world, INQ thwarted belongingness, ISI insomnia symptom severity, and UCLA-3 loneliness; Ps < .05), except for DSI-SS suicidal ideation severity (P = .187) and INQ perceived burdensomeness (P = .171). Based on the results of sensitivity analyses (see Endnote A), we elected to use listwise deletion to address missing data.

Data Analyses

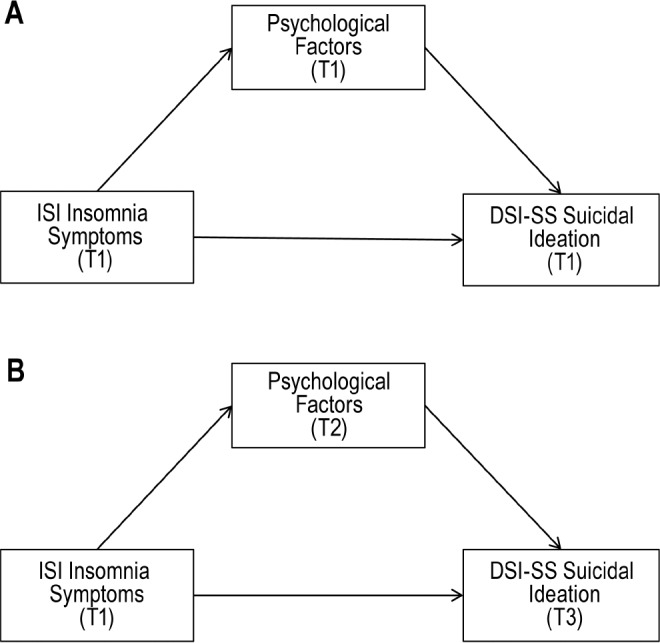

First, descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the sample and self-report measure scores. Next, for cross-sectional analyses, a series of bias-corrected bootstrap mediation analyses (1,000 bootstrap resamples; Model 434) were used to examine each T1 psychological factor (ie, DWLS disgust with self, DWLS disgust with others, DWLS disgust with the world, INQ perceived burdensomeness, INQ thwarted belongingness, and UCLA-3 loneliness) as a mediator of the relationship between T1 ISI insomnia symptom severity and T1 DSI-SS suicidal ideation severity (Figure 1A). Significant mediators from these cross-sectional analyses were then entered into a single model as parallel mediators, and pairwise contrasts were conducted to evaluate if any mediators were significantly stronger than other mediators. Additionally, we conducted exploratory moderated mediation analyses (Model 8 34) to evaluate if T1 INQ thwarted belongingness moderated the mediating effects of T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness and vice versa. For longitudinal analyses, a series of bias-corrected bootstrap mediation analyses (1,000 bootstrap resamples; Model 434) were used to examine each aforementioned psychological factor, assessed at T2, as a mediator of the relationship between T1 ISI insomnia symptom severity and T3 DSI-SS suicidal ideation severity, controlling for the corresponding T1 psychological factor and T1 DSI-SS suicidal ideation severity (Figure 1B). Significant mediators from these longitudinal analyses were entered as parallel mediators into a single model, and pairwise contrasts were conducted. We also used exploratory moderated mediation analyses (Model 8 34) to examine if T2 INQ thwarted belongingness moderated the mediating effects of T2 INQ perceived burdensomeness and vice versa, controlling for T1 DSI-SS suicidal ideation severity, T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness, and T1 INQ thwarted belongingness.

Figure 1. Proposed cross-sectional and longitudinal mediation models.

(A) Cross-sectional mediation model. (B) Longitudinal mediation model. DSI-SS = Depressive Symptom Inventory—Suicidality Subscale, ISI = Insomnia Severity Index, T1 = time 1 (baseline), T2 = time 2 (1-month follow-up), T3 = time 3 (2-month follow-up).

All mediation analyses were conducted utilizing the PROCESS macro34 in SPSS v20.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States). Mediators and pairwise contrasts were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not cross zero. Bootstrap mediation analyses are robust to non-normally distributed data35; thus, variables with marked skew and kurtosis (ie, DSI-SS, DWLS subscales) were not transformed. Also, though not the primary focus of this study, we examined our pattern of results when controlling for other related psychiatric symptoms (ie, depression and anxiety symptoms); these results are reported in footnotes.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

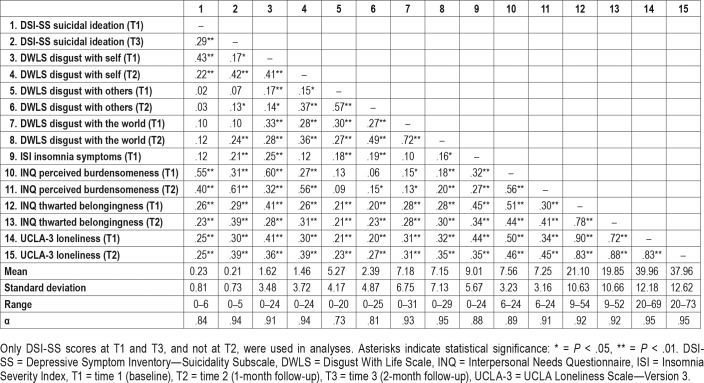

Means, standard deviations, ranges, and zero-order correlations for all self-report measures are presented in Table 1. At baseline, 27.0% (n = 61) of participants reported a lifetime history of suicidal ideation, 3.5% (n = 8) a lifetime history of suicide plans, and 4.4% (n = 10) a lifetime history of suicide attempts. Of the sample, 9.7% (n = 22), 9.7% (n = 22), and 4.9% (n = 11) reported current ideation (ie, DSI-SS total score > 0) at T1, T2, and T3, respectively; 1.8% (n = 4) of participants reported an onset of DSI-SS suicidal ideation from T1 to T3 (ie, denied ideation at T1 but reported ideation at T2 and/or T3). Additionally, based on the clinical cutoff for the DSI-SS (total score ≥ 327), 4.4% (n = 10), 3.5% (n = 8), and 3.5% (n = 8) of participants reported clinically significant suicidal ideation at T1, T2, and T3, respectively. Regarding insomnia symptom severity, 45.1% (n = 102), 34.5% (n = 78), and 32.3% (n = 73) of participants reported clinically significant insomnia symptoms based on the ISI clinical cutoff (total score ≥ 1029); 6.2% (n = 14) reported an onset of clinically significant ISI insomnia symptoms from T1 to T3.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations for self-report measures.

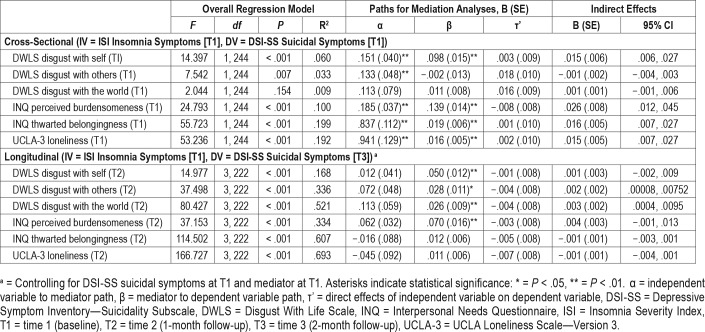

Cross-Sectional Mediation Analyses

The indirect effects of T1 ISI insomnia symptoms on T1 DSISS suicidal ideation were significant in the models examining T1 DWLS disgust with self (95% CI: .006, .027; abps = .018, 95% CI: .008, .032), T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness (95% CI: .012, .045; abps = .032, 95% CI: .019, .049), T1 INQ thwarted belongingness (95% CI: .007, .027; abps = .020, 95% CI: .010, .033), and T1 UCLA-3 loneliness (95% CI: .007, .027; abps = .019, 95% CI: .011, .031) as explanatory factors (see End-notes B and C). When all significant mediators were entered in the same model, only T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness (95% CI: .004, .044; abps = .028, 95% CI: .004, .048) remained a significant mediator. T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness did not significantly moderate the mediating effects of T1 INQ thwarted belongingness (95% CI: −.001, .001); likewise, T1 INQ thwarted belongingness did not significantly moderate the mediating effects of T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness (95% CI: −.001, 001). See Table 2 for detailed statistics for each model.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal bootstrap mediation analyses of possible explanatory factors in relationship between insomnia symptom severity and suicidal ideation severity.

Longitudinal Mediation Analyses

The indirect effects of T1 ISI insomnia symptoms on T3 DSISS suicidal ideation were significant in the models investigating T2 DWLS disgust with others (95% CI: .00008, .00753; abps = .003, 95% CI: .001, .010) and T2 DWLS disgust with the world (95% CI: .0004, .0095; abps = .005, 95% CI: .001, .013) as mediators, controlling for T1 DWLS disgust with others and T2 DWLS disgust with the world, respectively, and T1 DSISS suicidal ideation (see Endnote D). When both significant mediators were entered in the same model, only T2 DWLS disgust with the world remained a significant mediator (95% CI: .00004, .00761; abps = .003, 95% CI: −.0005, .0114). T2 INQ perceived burdensomeness did not significantly moderate the mediating effects of T2 INQ thwarted belongingness (95% CI: −.001, < .001), nor did T1 INQ thwarted belongingness significantly moderate the mediating effects of T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness (95% CI: −.001, < .001), controlling for T1 DSI-SS suicidal ideation, T1 INQ perceived burdensomeness, and T1 INQ thwarted belongingness. See Table 2 for statistics for each model.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify psychological factors that might account for the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation. In cross-sectional analyses, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, loneliness, and disgust with self each significantly mediated the association between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation. In contrast, longitudinal analyses revealed that only disgust with others and disgust with the world, assessed at 1-month follow-up, were statistical mediators of the relationship between baseline insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation severity at 2-month follow-up. Findings have implications for research on sleep disturbances and suicide risk, as well as suicide prevention efforts.

First, we note that our cross-sectional results largely align with those yielded by prior cross-sectional studies of these constructs in other populations.7,8,10,11 In addition to finding that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness significantly accounted for the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation, we also found that loneliness, assessed with a validated measure, was a significant mediator in cross-sectional analyses. This finding addressed a gap in prior studies that were only able to assess loneliness with a proxy measure.7,8 Our study also provides initial evidence that self-disgust may serve as an explanatory factor in the cross-sectional relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation. Much like with interpersonal factors, self-disgust may emerge among individuals with more severe insomnia symptoms due to the distress and impairment associated with lack of sleep.3 Disrupted sleep may also interfere with one's ability to process negative emotions,36 contributing to more extreme negative self-appraisals (ie, self-disgust). As Chu et al.19 note, this self-disgust can then lead to a desire to “destroy the object of revulsion” (p. 239; cf, anti-predator defensive reactions37)—in the case of self-disgust, this desire may be suicidal desire. Research is needed, however, to further explore self-disgust's relationship with insomnia and suicide risk.

Second, and perhaps most strikingly, our longitudinal analyses revealed that only disgust with others and disgust with the world significantly mediated the prospective relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation. Contrary to study hypotheses, these results suggest that disgust with others and the world—rather than self-disgust, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and loneliness—may be the specific mechanisms underpinning why insomnia may contribute to both the onset and exacerbation of suicidal ideation over time. As discussed in the conceptual review by Chu et al.,19 disgust with others and the world may have particularly deleterious effects by leading to withdrawal not only from social situations but also withdrawal “from all aspects of life” (p. 243). This type of extreme withdrawal has been observed in accounts of individuals who have died by suicide (cf, eusociality38).39 Thus, it may be that more so than negative beliefs about oneself (eg, disgust with oneself, feeling like a burden), negative beliefs about external domains (ie, disgust with others and the world) may facilitate the transition from sleep problems to suicidal ideation. Indeed, our results suggest that though insomnia may exacerbate other risk factors for suicidal ideation (eg, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness), its contribution to elevated disgust with others and the world— especially disgust with the world, given our single-model longitudinal findings—may be particularly pernicious regarding suicidal ideation.

Third, and notably, our cross-sectional findings contrasted entirely with our longitudinal results. These differential results provide a degree of support for statistical models highlighting issues inherent in utilizing cross-sectional mediation analyses to draw conclusions regarding the longitudinal relationship between variables.12,13 Only by collecting data across three time points and controlling for baseline clinical severity were we able to rigorously test possible mediators of the prospective relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation. We emphasize, however, that other factors may have also contributed to these disparate patterns of results. For instance, certain psychological constructs may exert mediating effects over a short time frame (eg, hours to days), whereas other constructs may play a more significant mediating role over longer periods of time (eg, months). In the case of our study, disgust with others and the world may have taken time to emerge and/or worsen among individuals suffering from insomnia, particularly given that disgust may be a relatively intense emotion.19 In contrast, other psychological factors, such as thwarted belongingness, may develop and/or worsen more quickly, perhaps due to insomnia's more immediate impacts on daily social functioning.40 Thus, it is possible that had we used shorter follow-up periods, our longitudinal results may have aligned more closely with our cross-sectional findings. It may also be that, at a cross-sectional level, certain constructs may simply co-occur, rather than exert mediating effects on one another over time. Our contrasting findings do underscore, though, the potential utility of adopting a multi-wave data collection strategy in future studies. This study design approach may not only illuminate mechanisms not observed in cross-sectional analyses but also improve our understanding of how time impacts the relationship between variables of interest.

Finally, our exploratory analyses did not support our hypothesis that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would interact to mediate the relationship between insomnia symptoms suicidal ideation. More specifically, thwarted belongingness did not significantly moderate the mediating effects of perceived burdensomeness, or vice versa, either in cross-sectional or longitudinal analyses. Previous cross-sectional studies utilizing moderated mediation analyses to evaluate these same constructs have produced equivocal findings. A multi-study investigation of military service members and veterans by Hom et al.8 failed to find significant moderated mediation effects in one sample (Study 2); however, in another sample, these effects were significant, with thwarted belongingness only serving as a significant mediator of the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk at low levels of perceived burdensomeness (Study 3). It may be, then, that insomnia is not necessarily associated with more severe suicide risk only when both interpersonal theory constructs are elevated. A further examination of these moderated mediation effects, especially in higher risk samples, is needed to enhance our understanding of this pattern of results. Measurement of the perceived intractability of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness is also indicated for future studies because active suicidal desire, as opposed to passive suicidal ideation, is only posited to emerge in the context of hopelessness about the tractability of these constructs.4,5

Clinical Implications

Though additional research is needed before definitive suicide prevention and treatment recommendations can be provided based on our findings, our study highlights possible therapeutic targets that merit further investigation. Specifically, our results suggest that addressing disgust with others and the world may help to prevent the trajectory from more severe insomnia symptoms to more severe suicidal ideation among young adults. As Chu et al.19 suggest, cognitive therapy41 may be one approach to targeting maladaptive thoughts about others and the world. Dialectical behavior therapy,42 a modality that focuses on enhancing skills to cope with negative emotions, may also serve to reduce disgust severity and impulses to act on feelings of disgust. In terms of implications for clinical assessment, our results indicate that it may be useful to consider disgust with others and the world when assessing suicide risk among individuals suffering from insomnia. Disgust with others and the world can be assessed using relatively brief instruments (eg, single-item assessments21); thus, inclusion of these constructs in standardized suicide risk assessment frameworks may be feasible.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was not without limitations. First, the overall sample was relatively low-risk, limiting generalizability and our ability to draw conclusions regarding how our constructs of interest may impact one another in high-risk samples. To enhance relevance to suicide prevention efforts, studies are needed to replicate our findings among high-risk samples and to evaluate more severe outcome measures. On this point, as noted, individuals who did not complete assessments at all three time points appeared to be of elevated clinical severity as compared to those who did complete all three survey batteries. Based on our sensitivity analyses, the exclusion of these individuals from our analyses did not appear to influence our outcomes. Even so, future studies may benefit from the adoption of measures to further incentivize study completion. Second, our sample was composed entirely of undergraduates from a single university, and the majority of our participants were female (89%) and identified as white/Caucasian (74%); thus, our findings may not be generalizable. We recommend replication studies among samples of greater sociodemographic and geographic diversity.

Third, though the follow-up periods used in our study were shorter than those utilized in the vast majority of other studies examining predictors of suicidal ideation,23 the use of shorter follow-up periods is indicated for future studies. Such studies will also allow us to test our conjecture that the mediating roles of psychological factors may vary based on the time frames evaluated. Ecological momentary assessments may be particularly useful measurement tools for such studies, especially because suicide risk is dynamic.43 Relatedly, the measures used in this study probed differing time frames, which may have impacted our ability to conclusively evaluate the temporal relationship between variables despite the use of three assessment points. A more precise assessment of constructs of interest is needed for future studies. Fourth, we relied solely on self-reported insomnia symptom severity. Using objective sleep measures44 in future studies may help illuminate specific sleep components and behaviors that contribute to increased suicide risk. Multiple modes of assessment will also serve to reduce the effects of common method variance. Additionally, alternative suicidal ideation measurement approaches (eg, implicit association tests45) may help circumvent concerns with the self-reporting of suicidal ideation. Finally, it is possible that factors not assessed in this study (eg, negative life events, posttraumatic stress symptoms) influenced our pattern of results. Other constructs that might explain the relationship between sleep and suicide risk should be included in future studies. As we improve our understanding of the relationship between sleep problems, psychological factors, and suicide risk, probing of more complex temporal relationships between these constructs using more than three time points will also be indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

This longitudinal study sought to evaluate various psychological factors (ie, disgust with oneself, others, and the world; perceived burdensomeness; thwarted belongingness; and loneliness) as mediators of the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation among young adults. Using data collected at three time points, each spaced 1 month apart, we found that only disgust with others and disgust with the world significantly mediated the relationship between more severe insomnia symptoms at baseline and more severe suicidal ideation at 2-month follow-up. Findings indicate that individuals with more severe insomnia symptoms may go on to experience more intense disgust with others and the world, which, in turn, contribute to more severe suicidal ideation. Consequently, disgust with others and the world—particularly disgust with the world—may serve as useful therapeutic targets in reducing suicidal ideation severity among individuals with more severe insomnia symptoms. Further research is needed to replicate our findings across other samples and to address the limitations of the current investigation. Even so, this study provides initial support for disgust with others and the world as explanatory mechanisms in the prospective relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation.

ENDNOTES

We utilized pattern-mixture models to examine whether the interactions between time and each missing data pattern were significantly associated with any of our predictor or outcome variables. We did not find any significant interactions in these analyses (Ps = .083–.567), indicat -ing that having missing data did not predict a change in these variables over time. Additionally, when we included missing data patterns as a covariate in our indirect effects models—thereby assessing the degree to which missing data patterns influenced outcomes—we failed to find significant effects. Given the results of our sensitivity analyses, listwise deletion was determined to be an acceptable approach to handling missing data.46–48

abps is interpreted as the number of standard deviations by which the dependent variable is expected to change for every 1-unit increase in the independent variable via the mediator.49

Findings remained the same when controlling for T1 anxiety symptoms (assessed by the Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI]) but not T1 depression symptoms (assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised [CESD-R]). We note, however, the limitations inherent in controlling for highly overlapping constructs in analyses (eg, controlling for depression when evaluating suicidal ideation as an outcome).50

No psychological factors remained significant mediators when controlling for T1 BAI anxiety symptoms or T1 CESD-R depression symptoms.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Work for this study was performed at Florida State University. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. This research was supported in part by grants from the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under Award No. (W81XWH-10-2-0181; W81XWH-16-2-0004). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the MSRC or Department of Defense. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DSI-SS

Depressive Symptom Inventory—Suicidality Subscale

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DWLS

Disgust With Life Scale

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- INQ

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire

- T1

time 1 (baseline)

- T2

time 2 (1-month follow-up)

- T3

time 3 (2-month follow-up)

- UCLA-3

UCLA Loneliness Scale—Version 3

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):e1160–e1167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littlewood D, Kyle SD, Pratt D, Peters S, Gooding P. Examining the role of psychological factors in the relationship between sleep problems and suicide. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;54:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(12):1313–1345. doi: 10.1037/bul0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu C, Hom MA, Rogers ML, et al. Is insomnia lonely? Exploring thwarted belongingness as an explanatory link between insomnia and suicidal ideation in a sample of South Korean university students. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):647–652. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hom MA, Chu C, Schneider ME, et al. Thwarted belongingness as an explanatory link between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation: findings from three samples of military service members and veterans. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu C, Hom MA, Rogers ML, et al. Insomnia and suicide-related behaviors: a multi-study investigation of thwarted belongingness as a distinct explanatory factor. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadorff MR, Anestis MD, Nazem S, Harris HC, Winer ES. Sleep disorders and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide: independent pathways to suicidality? J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golding S, Nadorff MR, Winer ES, Ward KC. Unpacking sleep and suicide in older adults in a combined online sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(12):1385–1392. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxwell SE, Cole DA, Mitchell MA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(5):816–841. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cacioppo JT, Patrick W. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hom MA, Hames JL, Bodell LP, et al. Investigating insomnia as a cross-sectional and longitudinal predictor of loneliness: findings from six samples. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortier-Brochu E, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(4):227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Michaels MS, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE. Discussing disgust: The role of disgust with life in suicide. Int J Cogn Ther. 2013;6(3):235–247. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanley IH, Rufino KA, Rogers ML, Ellis TE, Joiner TE. Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance (ASAD): a confirmatory factor analysis with 1442 psychiatric inpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;80:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker RP, Michaels MS, Rogers ML, Wingate LR, Joiner TE. Construct validity of a proposed new diagnostic entity: Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance (ASAD) J Affect Disord. 2016;189:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers ML, Chiurliza B, Hagan CR, et al. Acute suicidal affective disturbance: factorial structure and initial validation across psychiatric outpatient and inpatient samples. J Affect Disord. 2017;211:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(2):187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens J Adolescent Sleep Working Group, Committee on Adolescence. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e921–e932. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS: Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. [Accessed 2017]. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- 26.Mortier P, Demyttenaere K, Auerbach RP, et al. First onset of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in college. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joiner TE, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: reliability and validity data from the Australian National General Practice Youth Suicide Prevention Project. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(4):471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribeiro JD, Bodell L, Joiner TE. Disgust with self, others, and world in suicidality. Poster presented at: 46th Annual Convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; November 15-18, 2012; National Harbor, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastien C, Vallières A, Morin C. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu C, Klein KM, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Routinized assessment of suicide risk in clinical practice: An empirically informed update. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(12):1186–1200. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allison P. Missing Data: Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:168–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joiner TE, Stanley IH. Can the phenomenology of a suicidal crisis be usefully understood as a suite of antipredator defensive reactions? Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process. 2016;79(2):107–119. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2016.1142800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joiner TE, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Silva C. Suicide as a derangement of the self-sacrificial aspect of eusociality. Psychol Rev. 2016;123(3):235–254. doi: 10.1037/rev0000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robins E. The Final Months: A Study of the Lives of 134 Persons Who Committed Suicide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 2000;23(2):243–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linehan MM. DBT® Skills Training Manual, Second Edition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. The importance of temporal dynamics in the transition from suicidal thought to behavior. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2016;23(1):21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1059–1068. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nock MK, Banaji MR. Assessment of self-injurious thoughts using a behavioral test. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(5):820–823. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sterba SK. Pattern mixture models for quantifying missing data uncertainty in longitudinal invariance testing. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 2017;24(2):283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Jansen I, et al. Analyzing incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data. Biostatistics. 2004;5(3):445–464. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychol Methods. 1997;2(1):64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogers ML, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Chiurliza B, Podlogar MC, Joiner TE. Conceptual and empirical scrutiny of covarying depression out of suicidal ideation. Assessment. 2018;25(2):159–172. doi: 10.1177/1073191116645907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]