ABSTRACT

Poverty drives tuberculosis (TB) rates but the approach to TB control has been disproportionately biomedical. In 2015, the World Health Organization's End TB Strategy explicitly identified the need to address the social determinants of TB through socio-economic interventions. However, evidence concerning poverty reduction and cost mitigation strategies is limited. The research described in this article, based on the 2016 Royal College of Physicians Linacre Lecture, aimed to address this knowledge gap. The research was divided into two phases: the first phase was an analysis of a cohort study identifying TB-related costs of TB-affected households and creating a clinically relevant threshold above which those costs became catastrophic; the second was the design, implementation and evaluation of a household randomised controlled evaluation of socio-economic support to improve access to preventive therapy, increase TB cure, and mitigate the effects of catastrophic costs. The first phase showed TB remains a disease of people living in poverty – ‘free’ TB care was unaffordable for impoverished TB-affected households and incurring catastrophic costs was associated with as many adverse TB treatment outcomes (including death, failure of treatment, lost to follow-up and TB recurrence) as multidrug resistant (MDR) TB. The second phase showed that, in TB-affected households receiving socio-economic support, household contacts were more likely to start and adhere to TB preventive therapy, TB patients were more likely to be cured and households were less likely to incur catastrophic costs. In impoverished Peruvian shantytowns, poverty remains inextricably linked with TB and incurring catastrophic costs predicted adverse TB treatment outcome. A novel socio-economic support intervention increased TB preventive therapy uptake, improved TB treatment success and reduced catastrophic costs. The impact of the intervention on TB control is currently being evaluated by the Community Randomized Evaluation of a Socio-economic Intervention to Prevent TB (CRESIPT) study.

KEYWORDS: catastrophic costs, conditional cash transfers, End TB Strategy, poverty, social determinants, social protection, socio-economic support, TB

Introduction

Over a century ago, Virchow recognised that tuberculosis (TB) was a social disease.1 Since then, Koch's discovery of the bacillus and the discovery of streptomycin and other antimicrobials provided humankind with a means to both diagnose and treat TB. Yet TB rates in Europe fell during the industrial revolution, prior to either the discovery of the TB bacillus or TB antimicrobial therapy. This decrease was predominantly caused by changes in social determinants such as improved living conditions 2,3 and nutrition.4,5

TB rates worldwide are declining slowly and remain unacceptably high: a third of the world's population is estimated to be infected with TB and 1.5 million people died of TB in 2014, the majority of whom were impoverished people living in resource-constrained settings.6 Thus, TB remains a social disease inextricably linked in a vicious cycle with poverty. Specifically, being poor continues to increase the risk of acquiring TB infection and disease7–9 and having TB disease worsens poverty in TB-affected households.10–12 However, the global TB control and research strategy has been disproportionately focused on a biomedical rather than socio-economic response to the epidemic. Despite helping to cure millions of people of TB disease,8 a biomedical-only response to TB will not be enough to eradicate TB this century. To end TB globally, a more holistic approach, which continues to incorporate biomedical responses and also addresses the broader socio-economic determinants of this disease, is required.11,13–16

Addressing the social determinants of TB is not a new concept. Almost 100 years ago, the Papworth study (a socio-medical experiment performed at the Papworth Village Settlement in England) showed that stable employment and adequate housing and nutrition for households of parents with active TB disease decreased the incidence of TB infection and disease in their children.2 Nevertheless, since the advent of the antibiotic era, such social and economic support interventions received less attention and the response to TB became focused almost solely on the biomedical.

In the 2015 End TB Strategy, the World Health Organization (WHO) cited mitigation of TB-related costs and provision of socio-economic support to TB-affected households as key pillars in the global response to TB for the first time.16 However, rigorous evidence with which to guide society, policymakers and national TB programmes on the implementation of cost mitigation and TB-specific socio-economic interventions (eg focused only on TB-affected people) remains extremely limited.9,17,18

For over a decade, our research group (www.ifhad.org) has worked with TB-affected households in the shantytowns of Callao, Peru – an area in which approximately a third of the population live on less than $1.50 a day and that has pockets of gun crime and drug addiction. From 2007–11, we conducted an assessment of innovative socio-economic interventions against TB (ISIAT) in 16 shantytown communities of Callao.15 The interventions had two dimensions:

education, community mobilisation and psychosocial support to increase uptake of TB care

food transfers, microcredit, microenterprise and vocational training to reduce poverty.

In a pre- versus post-intervention analysis, the intervention increased preventive chemotherapy in household contacts, and HIV testing and TB treatment completion in TB patients.15

Extending the ISIAT project findings, the IFHAD team performed a randomised controlled evaluation of a socio-economic support intervention incorporating conditional cash transfers in 32 shantytown communities of Callao. The research was carried out in two phases: phase 1 aimed to measure and define catastrophic costs of accessing ‘free’ TB care and their impact on TB treatment outcomes; and phase 2 aimed to design, implement and evaluate the TB-specific socio-economic intervention, including conditional cash transfers to enhance access to TB preventive therapy, improve TB treatment outcomes and mitigate the effects of catastrophic costs in supported TB-affected households. This article summarises the findings of this research as presented during the Linacre Lecture at the Royal College of Physician's Advanced Medicine conference in January 2016.

Phase 1: defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multidrug resistance

While many countries aim to offer ‘free’ TB treatment to their patients, this may only cover some diagnostic tests and anti-mycobacterial medications. Patients and their households may incur hidden TB-related costs such as direct ‘out-of-pocket’ expenses (including transport, symptom-relieving medicines and additional food) or indirect expenses associated with lost income.19–22 A goal of the WHO's End TB Strategy mandates eradicating catastrophic costs for TB-affected families by 2020.14 However, hidden TB-related costs remain understudied and a unifying definition of catastrophic costs is awaited.14,23–26

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of 876 TB patients (11% of whom had MDR TB) that used repeated TB patient interviews (at treatment initiation, then at 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 weeks of treatment) to quantify changes in income and hidden TB-related costs prior to and throughout treatment. The socio-economic section of the questionnaire used can be accessed at https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/31465 or in a related publication.11 This better characterised TB-related costs, their association with adverse TB outcome and contributed to an evidence-based definition of catastrophic costs that is relevant both financially and clinically (eg relating to TB patients’ and their contacts’ health outcomes).

The study took place in 32 shantytown communities in Callao, Peru, with an estimated population of one million people. The annual TB notification rate across these communities was 206 new cases per 100,000 people between 2011 and 2013, greater than the national rate of 95 per 100,000 people.

Measured costs included direct expenses and lost income. Direct expenses included direct medical expenses (medical examinations and prescribed medicines) and direct non-medical expenses (natural non-prescribed remedies, TB care-related transport, extra food and other miscellaneous expenses). With regard to direct medical expenses, while sputum sample testing and chest radiograph for diagnosis of TB and anti-mycobacterial therapy for treatment of TB is provided free by the Peruvian national TB control programme, patients may have multiple consultations prior to diagnosis (eg seen with fever and cough but not tested for TB), for which they may incur costs. Lost income was the income the patient estimated that the household lost because of TB illness or tuberculosis-related time off work (such as attending clinics) since the previous interview. Poverty was measured using a composite household poverty index in arbitrary units derived by principal component analysis from 13 variables, as described.15 A threshold for catastrophic costs was calculated by plotting the sensitivity, specificity and population attributable fraction for adverse TB outcome against total household costs as a proportion of annual household income. Adverse TB outcome was defined as death, loss to follow-up or treatment failure during therapy, or recurrence within 2 years.

Results

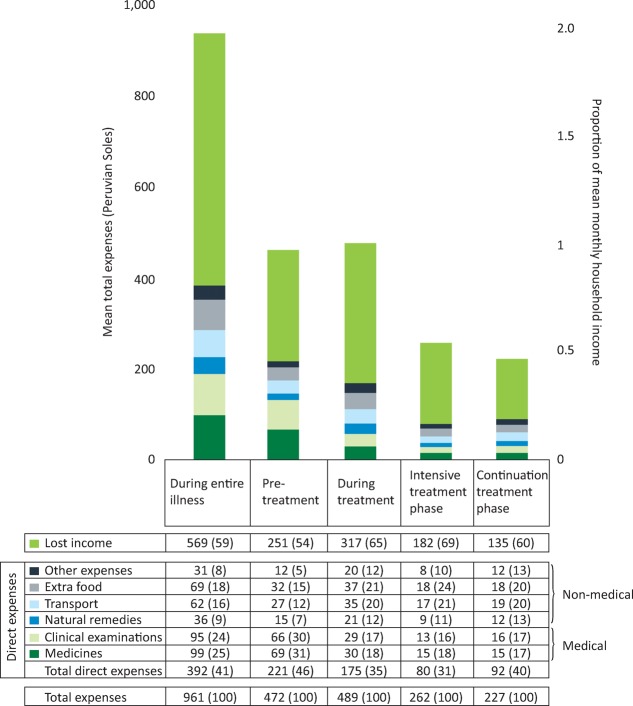

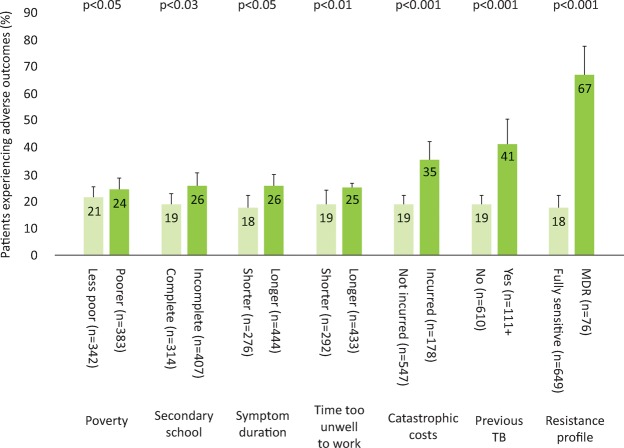

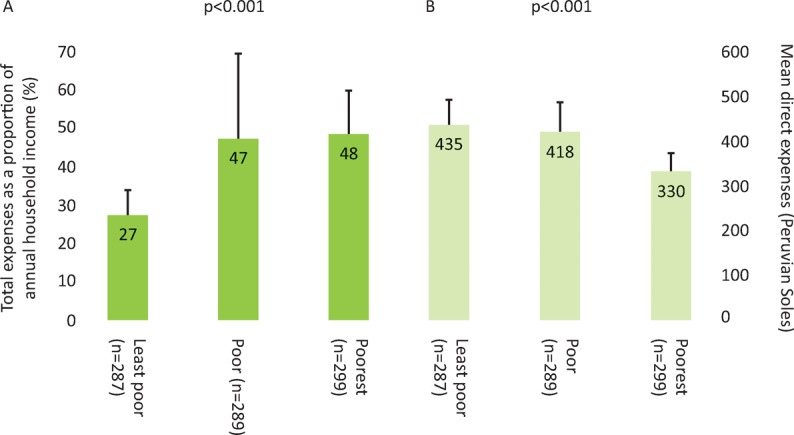

Accessing TB care cost TB-affected households approximately 2 months of their annual household income with half of the costs being incurred prior to the start of TB treatment and half consisting of lost income (Fig 1). In poorer households, costs were lower but constituted a higher proportion of the household's annual income: 27% (95% CI 20–43%) in the least poor houses versus 48% (95% CI 36–50%) in the poorest (Fig 2). 23% (166/725) of patients with a defined treatment outcome had an adverse outcome. Total costs ≥20% of household annual income was defined as catastrophic because this threshold was most strongly associated with adverse TB outcome. Catastrophic costs were incurred by 345 households (39%). Adverse treatment outcome was independently associated with MDR TB (odds ratio (OR)=8.4 (95% CI 4.7–15), p<0.001) and catastrophic costs (OR=1.7 (95% CI 1.1–2.6), p=0.01, Fig 3). The adjusted population attributable fraction of adverse outcomes explained by catastrophic costs was 18% (95% CI 6.9–28%), similar to that of MDR TB (20% (95% CI 14–25%)).

Fig 1.

Average lost income, constituent direct expenses and total expenses by treatment stage. n=876 *Peruvian currency, 3 Soles = 1 US $. The numbers in parentheses represent percentage of total expenses. ‘Medical’ expenses are defined as the sum of direct expenses for medicines and clinical exams; ‘non-medical’ expenses are defined as the sum of direct expenses for natural remedies, TB care-related transport, extra food and other TB-related expenses. 23/876 (2.6%) of the TB patient cohort had direct expenses of 0 Peruvian soles and 14/876 (1.6%) had total expenses of 0 Peruvian soles and for analysis; these zero values were replaced by 0.5 Peruvian soles per day (with the midpoint between zero and the lowest measured unit, one Sole). Reproduced with permission from Wingfield et al.11

Fig 2.

Expenses and economic burden of tuberculosis illness across poverty terciles. A – total expenses as proportion of annual income; B –direct expenses. Reproduced with permission from Wingfield et al.11

Fig 3.

Percentage of patients experiencing an adverse tuberculosis (TB) outcome analysed by poverty, education level, symptom duration, previous TB, catastrophic costs and resistance profile. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals; p-values correspond to the association of each variable with adverse TB outcome in univariable logistic regression except for poverty and symptom duration that were analysed as continuous variables. In multivariable regression analysis, the following variables remained independently associated with adverse TB outcome: time too unwell to work (p=0.02), catastrophic costs (p=0.003), having had a previous episode of TB (p=0.004) and currently having multidrug resistant (MDR) TB (p<0.0001). Reproduced with permission from Wingfield et al.11

Discussion

This study defined a novel, evidence-based threshold of total costs greater than 20% of annual household income as catastrophic for TB-affected households because it was associated with increased likelihood of adverse TB outcome, independent of MDR TB status. Analysis of the population attributable fraction also implied that almost a fifth of adverse TB outcomes could be averted by eliminating catastrophic costs from the study population, similar to MDR TB. In addition, as has been shown in other settings,19–21 accessing free TB care was expensive for TB patients and the poorest households incurred the greatest costs as a proportion of their household income – typifying the ‘medical poverty trap’.27,28

This study added a new dimension to the social protection TB literature by showing how catastrophic costs can also have significant clinical implications: loss of income and increasing hidden costs have previously been associated with poor treatment adherence and high dropout rates in TB patients 20,29,30 but their independent effect on long-term TB outcome has not been previously characterised. We hypothesised that the relationship we found between catastrophic costs and adverse TB outcome may relate to a number of factors along the causal pathway from TB susceptibility to illness to recurrence, including inadequate nutrition due to lower food spending, more severe TB disease and barriers to cure because of the disproportionate hidden costs associated with adherence to and completion of treatment.

The findings of phase 1 of our research suggested that TB-related costs incurred by TB-affected households are not only financially but also clinically relevant – influencing TB treatment outcomes. Thus, TB control interventions must consider addressing TB as an infectious and socio-economic problem. The innovative catastrophic costs’ threshold was subsequently endorsed by WHO within their global tool to estimate country-specific TB-related and catastrophic costs of TB patients and their TB-affected households. The tool, which builds on the published ‘tool to estimate patients’ costs’27 and includes measurement of lost income in addition to direct out-of-pocket expenses, is being piloted and rolled-out in sentinel countries from 2015 onwards, prior to being refined and implemented globally.

Phase 2: designing, implementing and evaluating a socio-economic intervention to mitigate the effects of catastrophic costs, enhance access to TB preventive therapy and improve TB treatment outcomes

Enhancing access to TB preventive therapy and treatment is likely to improve TB prevention and cure.31–34 Alongside the existing biomedical approach, complementary strategies, including socio-economic support, are required to meet global TB control goals.35–52

Social protection and socio-economic support interventions consist of policies and programmes designed to reduce poverty and vulnerability by improving people's capacity to manage social and/or economic risks,53 and includes health insurance, food assistance, travel vouchers and cash transfers.54 Cash transfers generally provide economic support to impoverished people with the aim of moving them out of extreme poverty and vulnerability while improving human capital.55–60 Following on from the phase 1 research, we hypothesised that defraying TB-related costs of TB-affected households using cash transfers could enhance access to TB preventive therapy, improve TB treatment outcomes, mitigate the effects of catastrophic costs and, potentially, control TB.61

However, there was little operational evidence to guide implementation or evaluate the impact of TB-related socio-economic support, including cash transfer interventions.9,15,17,18,54–56,62–68 Building on the lessons learnt during the ISIAT project,15 extensive expert and TB civil society consultation,54 a systematic review of cash transfer interventions55 and the phase 1 published research,11 our IFHAD research group was funded by the Joint Global Health Trials (a consortium of Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and the UK Department for International Development) to undertake the Community Randomized Evaluation of a Socio-economic Intervention to Prevent TB (CRESIPT) project. The conception, design, and implementation of the complex TB-specific socio-economic intervention is described in more detail elsewhere.31 Here, we report the economic and clinical effects of the household randomised controlled pilot evaluation of the intervention, which aimed to refine the intervention for the CRESIPT project while rigorously assessing the impact of the intervention on reducing catastrophic costs, improving access to TB preventive therapy and increasing TB cure and treatment success.

Methods

Intervention

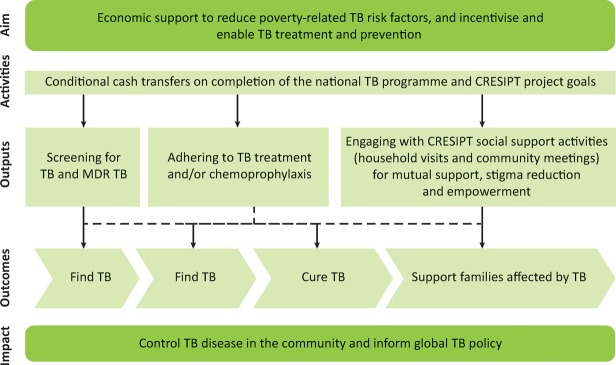

The intervention aimed to increase screening for TB in household contacts and MDR TB testing in TB patients; adherence to TB treatment and preventive therapy and engagement with socio-economic support activities. The conceptual framework of the integrated intervention is shown in Fig 4 and comprised economic and social support:

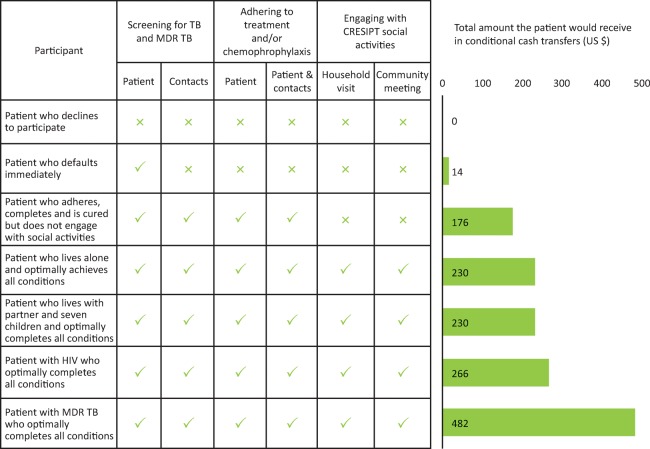

Economic support consisted of conditional cash transfers throughout treatment to defray average household TB-related costs thereby reducing TB risk factors while also incentivising and enabling equitable access to care. Cash transfers were provided on completing each month of continued treatment, allowing a home visit from the project team, the household attending a participatory community meeting, and completion of treatment by the patient and preventive therapy by relevant contacts (Table 1).The cash transfers were designed so that if a patient achieved all possible conditions and thereby received all possible cash transfers throughout treatment, this would largely defray the direct out-of-pocket expenses for their entire illness that were previously found to be 10% of annual household income in this study site (US $230). Seven potential cash transfer scenarios are shown in Fig 5.

Social support consisted of household visits and participatory community meetings performed by the CRESIPT research nurses and members of the local TB civil society, which aimed to provide information, mutual support and empowerment, and stigma reduction. The household visits were made shortly after patients were started on treatment and focused on education concerning TB transmission, treatment, preventive therapy and domestic finances. The community meetings took place monthly in each study site community.69 The meetings re-emphasised the educational themes of the household visit through interactive games and workshops, and developed an event entitled ‘TB Club’ in which participants shared TB-related and other life experiences within a mutually supportive group setting.70

Fig 4.

Conceptual framework of the tuberculosis-specific socio-economic intervention. CRESIPT = Community Randomized Evaluation of a Socio-economic Intervention to Prevent TB; MDR = multidrug resistant; TB = tuberculosis. Reproduced with permission from Wingfield et al.31

Table 1.

Conditional cash transfer scheme

| Double incentives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Output | Condition | What the person with TB and their household members are required to do to receive a double incentive | What each TB-affected family will receive in Soles |

| Screening for TB and MDR TB | Patient: sputum sample | Give a sputum sample prior to starting treatment and complete the questionnaire with the research nurse. The national TB programme must have registered the person with TB in their health post's TB patient register. | 40 ($14) |

| Contact: TB screening | All (100%) of the people registered as living in the same house as the person with TB attend their medical appointment or give a sputum sample (that has a result) to rule out TB. Those people who need to take medicine to prevent TB (chemoprophylaxis) or TB treatment must have started it. Contacts who do not need to take such treatment must be confirmed in the medical treatment cards. | 150 ($54) | |

| Adherence to TB treatment or chemoprophylaxis | Patient: adherence to treatment | Sensitive/non-MDR patients (including those with HIV) during the first 50 doses of treatment: each 25 does (approximately each month) of TB treatment taken, missing no more than 2 doses. | 50 ($18) |

| MDR patients (including those with HIV) during the first 150 doses of treatment: each 25 doses (approximately each month) of TB treatment taken, missing no more than 2 doses. | 50 ($18) | ||

| Sensitive/non-MDR patients (including those with HIV) after the first 50 doses to the end of treatment: each 24 doses (approximately 2 months) of TB treatment taken, missing no more than 1 dose. | 50 ($18) | ||

| MDR patients (including those with HIV) after the first 150 doses to the end of treatment: each 50 doses (approximately 2 months) of TB treatment taken, missing no more than 2 doses. | 50 ($18) | ||

| Patient and contacts: completion of TB treatment and chemoprophylaxis | The person with TB completes their TB treatment and all (100%) of the people who live with them, who started chemoprophylaxis to prevent TB, finish their chemoprophylaxisis. | 100 ($36) | |

| Engage with CRESIPT social activities | Patient and contacts: home visit | In the first week following recruitment to the project, allow the CRESIPT team to visit the TB patient's house, complete the questionnaire (if necessary) and list all of the people who live in the same house as them. | 50 ($18) |

| Patient and contacts: community meetings | By 3 months following recruitment, the person with TB and all (100%) of the people that the CRESIPT team listed as living in the same house as them attend at least one CRESIPT community meeting. | 100 ($36) | |

| Complete all conditions | The person with TB and all of their contacts complete all of the above project conditions, including adhering to treatment for the duration of treatment. | 640 ($230) | |

CRESIPT = Community Randomized Evaluation of a Socio-economic Intervention to Prevent TB; MDR = multidrug resistant; TB = tuberculosis

Fig 5.

Cash transfer received by participants in seven different potential scenarios during intervention implementation. Typically, in Peru, treatment of TB in people with non-MDR TB has a duration of 6 months; in people with HIV TB co-infection, treatment lasts 9 months; and in people with MDR TB, treatment lasts 24 months. MDR = multidrug resistant; TB = tuberculosis. Reproduced with permission from Wingfield et al.31

Participants

Any patient initiating treatment with the Peruvian national TB control programme was invited to participate between 10 February and 14 August 2014. Patients were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to give written, informed consent. For patients who were minors, a parent or guardian was asked to give informed consent and patients who were old enough were also invited to provide their assent to participate.

Randomisation

Patient households were randomised (at a 1:1 ratio in restricted blocks of 30 per health centre according to predefined random number tables) to the control or intervention arm:

control – TB-affected households in which a TB patient received the Peruvian national TB control programme standard of care only

intervention – TB-affected households in which a TB patient received the Peruvian national TB control programme standard of care plus the socio-economic intervention.

Preventive therapy

The most recent Peruvian TB programme guidelines that applied throughout this study recommended that preventive therapy be provided to all contacts under 5 years old of a patient with non-MDR pulmonary TB (unless the contact had had previous TB disease), and preventive therapy should also be considered for contacts aged 5–19 years of a patient who had a tuberculin positive skin test indicating latent TB infection and were a contact of a patient with non-MDR pulmonary TB.71 However, tuberculin was generally unavailable throughout this study, which meant that decisions regarding preventive therapy in contacts aged 5–19 years were predominantly based on clinical grounds alone (eg sputum smear positivity, time spent with index case) and thus heterogeneous across community health posts. Preventive therapy consisted of a 6-month course of daily isoniazid that was collected weekly from health posts by patients and taken unsupervised at their home.71

Treatment

The Peruvian national TB control programme offered free TB diagnostic testing to all suspected TB patients who, once diagnosed, received free anti-TB directly observed therapy (DOT) administered at health posts.71 TB treatment outcome data were collected collaboratively with the Peruvian national TB control programme from their treatment cards at the time of final follow-up and were not influenced by the research. Peruvian TB programme outcomes were consistent with those defined by the WHO.72

The Peruvian TB programme define cure of drug-susceptible TB as a patient with bacteriologically confirmed TB at diagnosis who completes treatment and has a negative sputum smear during the final month of treatment.71 This involved confirmation during clinical assessment by a national TB programme physician to evaluate symptoms, examination, weight trend and, when necessary, investigations such as chest radiographs and blood tests. Patients who completed their TB treatment course but did not complete the required sputum testing and/or physician review were classified as having completed treatment. Other programmatic outcomes were death (all-cause mortality during TB treatment), failure of treatment (as determined by the physician and/or demonstrated by positive sputum microscopy/culture after 4 months of treatment), loss to follow-up and unknown outcome (patient relocated to another region and/or inability to determine outcome). The Peruvian TB programme defined treatment success as patients who completed treatment or were cured.

An additional project definition was ‘continuing on treatment’ after our 28-week follow-up interview. MDR TB patients, whose treatment duration commonly extends to 24 months, were defined as continuing treatment if still taking TB treatment at this 28-week follow-up interview. This was also the case for patients with drug-sensitive TB and prolonged treatment courses either due to poor adherence (but not loss to follow-up) or based on clinical grounds.

Study outcomes

The primary study outcome was uptake of TB preventive therapy in contacts under 20 years of age in intervention households compared with control households. Completion of TB preventive therapy was operationally defined in line with Peruvian national guidance: contacts who started and took 6 months (24 weeks) of preventive therapy (as documented in their preventive therapy treatment cards).71

Secondary study outcome was the national TB control programme confirmed TB cure in patients as described above. This analysis evaluated patients with cure versus patients without cure without any exclusions (intention-to-treat); and treatment success (sum of completed treatment and confirmed cure) versus no treatment success without any exclusions (intention-to-treat).73

Tertiary study outcome was TB-related costs defrayed and catastrophic costs mitigated calculated for intervention households and compared with control households (who did not receive any conditional cash transfers).

Feedback

At 24 weeks following treatment initiation, intervention household participants were asked to complete a mixed-methods exit questionnaire to collect feedback on, and suggest improvements to, the social and economic support activities.

Analysis

Methods for collecting TB-related costs data replicated those used during phase 1 of the research. Data at the household and individual (patient or contact) level were used for intention-to-treat and supplementary analyses with adjustments for household clustering using robust standard errors because there was more than one household contact per patient in most households. The primary and secondary outcome were analysed by univariate logistic regression and multiple logistic regression adjusted for household clustering and known confounders measured at baseline (including household-level factors such as poverty, household crowding, head of household's highest education level, monthly income and food insecurity; and patient-level factors such as age, gender, employment status and TB resistance profile) that generated adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for relevant, contributory socio-economic and health factors. Time-to-event analysis was performed in order to generate a crude, unadjusted log-rank value for difference between the number of weeks of preventive therapy taken by household contacts from intervention versus supported households.

Results

Participants

The recruitment period was from 10 February 2014 to 14 August 2014 when the a priori study sample size was reached and data collection on TB-affected household costs continued until 1 June 2015. Fig 6 shows TB-affected household recruitment and participation: 312 TB patients from separate households were invited to participate, of whom 90% (282/312) were recruited. Of these, 147 were randomised to the control arm and received normal standard of care only and 135 were randomised to the intervention arm and additionally received the socio-economic intervention. 68% of patients had sputum smear-microscopy positive TB. 9% (24/282) of patients had MDR TB, none of whom had been cured or completed treatment during the study because, in Peru, MDR TB treatment generally requires at least 2 years of continuous antibiotic therapy tailored to individuals’ resistance profiles. No substantive baseline imbalances were found between intervention and control patients. Of the intervention TB-affected households, 98% (132/135) completed final follow-up. Nevertheless, all 135 intervention TB-affected households had TB-related costs data available for analysis. Patients had an average of five contacts, 97% (1,290/1,331) of whom were recruited. 40% (518/1,290) of recruited contacts were under the age of 20 years; of these, 410 completed follow-up.

Fig 6.

Participant recruitment and randomisation. Recruitment constituted completing informed consent and a recruitment questionnaire. Dashed arrows refer to participants who were not included in the final analysis. *Secondary outcome analysis; **primary outcome analysis. Reproduced with permission from Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D et al. The economic effects of supporting tuberculosis-affected households in Peru. Eur Respir J 2016;48:1396–410.

Conditional cash transfers

122/135 (90%) of intervention TB-affected households received at least one conditional cash transfer. These 122 intervention TB-affected households received a total of 890 conditional cash transfers (80% of potential conditional cash transfers), receiving on average a total of 520 Peruvian Soles (US $173), which is equivalent to 3.5% of average TB-affected household annual income or 42% of average TB-affected household monthly income.31,74

Study outcomes

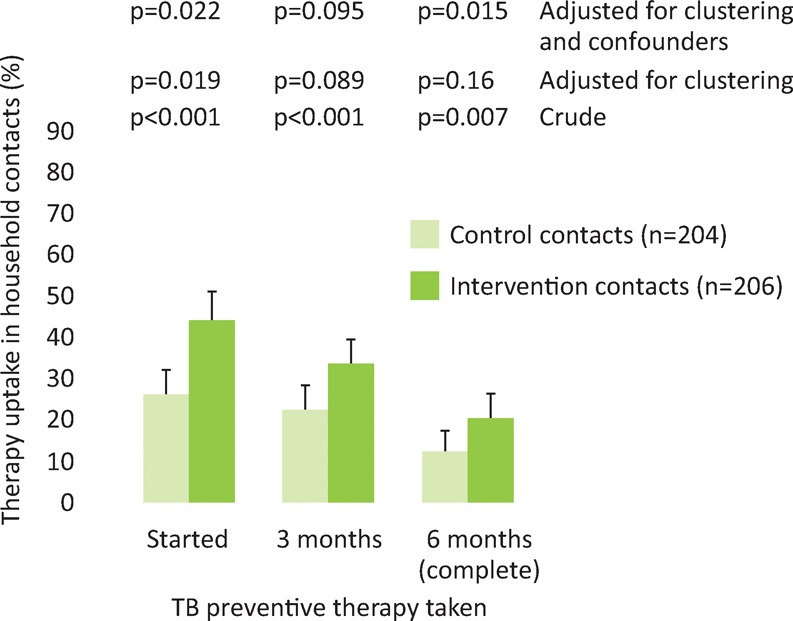

Contacts under 20 years of age from intervention households were more likely than those from control households to start preventive therapy (44% versus 26%, aOR 2.2 (95% CI 1.1–4.2), p=0.022, Fig 7). Although crude analysis showed that household contacts were more likely to complete 3 and 6 months of preventive therapy, these increases were not significant after adjusting for household clustering (completion of 3 months 33% versus 22%, aOR 1.8 (95% CI 0.90–3.7), p=0.095 and completion of 6 months 20% versus 12%, aOR 1.9 (95% CI 0.79–4.6), p=0.15, Fig 7).

Fig 7.

Uptake, completion of 3 months and completion of 6 months of tuberculosis preventive therapy in intervention (n=206) and control (n=204) contacts under 20 years of age. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals; p-values are derived by logistic regression.

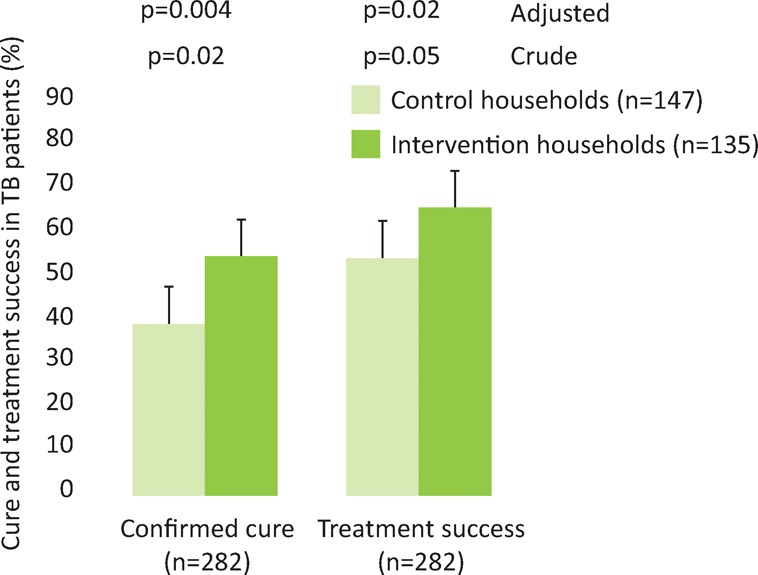

The intention-to-treat-analysis showed that patients from intervention households were more likely than those from control households to have confirmed cure (51% (95% CI 43–60%) versus 37% (95% CI 30–45), aOR 1.8 (95% CI 1.1–2.9), p=0.02, Fig 8). In addition, patients from intervention households were more likely to have treatment success than patients from control households (64% versus 53%, aOR 1.8 (95%CI 1.1–2.9), p=0.02, Fig 8).

Fig 8.

Cure and treatment success in tuberculosis patients. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals; p-values are derived by logistic regression.

Overall, 36% of patient households incurred catastrophic costs. Compared with control households, intervention households were less likely to incur catastrophic costs (30% (95%CI 22–38) of intervention households versus 42% (95%CI 34–50) of control households, p=0.002, Fig 9).

Fig 9.

Catastrophic costs incurred by intervention (n=132) and control (n=140) households. The top p-value is regression analysis adjusted for confounders, including food insecurity, poverty level, household crowding, highest level of education of head of household, resistance profile of patient, and employment of patient. Reproduced with permission from Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D et al. The economic effects of supporting tuberculosis-affected households in Peru. Eur Respir J 2016;48:1396–410.

Feedback

99 intervention households provided feedback. The proportion of those households rating the following socio-economic activities as good or excellent was: home visits 89/99 (90%), health-post visits 82/99 (83%), TB workshops 81/99 (82%), TB Clubs 79/99 (80%) and conditional cash transfers 83/99 (84%). Participant feedback and suggested improvements are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of tuberculosis-affected households’ qualitative feedback. Feedback focused on positive aspects, aspects to improve on and suggested improvements of the social and economic elements of the intervention

| Intervention activity | Positive | Aspect to improve on | Suggested improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Improved information and education

Enhanced emotional and mutual support Increased self-confidence and esteem Motivating |

Health-post, home visits, TB workshops and TB clubs too infrequent

Lack of forewarning and difficulty coordinating times of social activities Workshops and clubs could be more dynamic |

Increase health-post visits to at least weekly and home visits, TB workshops and clubs to twice a month

Earlier formal invitation to activities followed up by reminder phone call or text Include better audiovisuals: especially music and videos (including patient testimonies) |

| Economic | Enabled participants to buy better food and cover travel costs to health-post for directly observed therapy or contact screening

Cash transfers were encouraging and motivating |

Transfers not punctual, too infrequent and not enough

Complications of bank transfers included difficulty withdrawing cash, wasted visits when cash was not yet deposited and hidden bank charges |

Increase cash transfer amounts, allow maximum 3-day wait to arrive and provide cash transfers twice a month

Inform household when cash transfers have arrived Allow participants to save up cash transfers (eg have all transferred at one time) |

TB = tuberculosis

Discussion

During the CRESIPT pilot study, we designed, implemented, refined31 and evaluated a novel TB-specific socio-economic intervention, including cash transfers in a resource-constrained setting. The intervention proved to be acceptable and feasible,69 decreased the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs, and increased TB preventive therapy uptake and adherence in contacts, and TB cure and treatment success in patients.

Despite more than one-third of the TB-affected households experiencing catastrophic costs and thus being at increased risk of adverse treatment outcome,75 intervention households were less likely to incur catastrophic costs than control households. This finding is encouraging because it has the potential to contribute to the WHO's goal of eliminating catastrophic costs by 2020. During planning of the intervention, it had been estimated that, if implemented nationally, this conditional cash transfer programme would increase the Peruvian TB programme budget by approximately 15% per patient.22 Focus group discussions with key stakeholders, including local staff of the Peruvian TB programme and a civil society of TB-affected people, suggested that such an increase in programme expenditure was locally appropriate, affordable and potentially sustainable.13,15

The finding that this intervention increased TB preventive therapy uptake and the number of weeks of preventive therapy taken is important because non-adherence to TB preventive therapy is frequent32–35,46,76–80 and leads to higher rates of secondary TB. Nevertheless, it must be noted that despite a trend towards increased TB preventive therapy completion in the intervention contacts, this was not statistically significant and many contacts who were probably eligible for TB preventive therapy did not complete it despite being offered our socio-economic intervention. A potential reason for this may be that conditional cash transfers for preventive therapy were not given monthly like they were for TB treatment and total cash transfers did not completely mitigate households’ TB-related costs. Other reasons include social activities not leading to lasting positive health-behaviour changes over the 6 months of required preventive therapy.

While our findings suggest that conditional cash transfers may contribute to improved patient outcomes (perhaps through diminishing food insecurity during TB treatment as well as improved access to medical care), it must be noted that the intervention went beyond cash transfers by offering education during household visits and participatory community meetings to inform and promote stigma reduction, inclusiveness and empowerment. This social support focused on risk factors for non-adherence to preventive therapy such as being female and/or belonging to a marginalised group,43,81–83 age,83,84 illegal drug use,46 homelessness,47 alcohol misuse,85 and TB-affected families’ and individual's own knowledge, attitudes and perceptions.80,86 Although our group had originally applied for funding to perform a 2×2 factorial study evaluating economic support versus social support and socio-economic support versus standard of care, the sample size required was prohibitive and that application was not funded. The final funded study design of this CRESIPT pilot study did not allow analysis of the differential impact of the social support component and the economic support component of cash transfers on access to preventive therapy and TB cure rates. Nevertheless, in the field of HIV, conditional cash transfers interventions have often been complemented with health education for beneficiaries, and it has been suggested that, without education or social support, conditional cash transfers are unlikely to have an impact on health outcomes.87 Thus, optimising social support, education and information, and addressing specific aspects of poverty – such as food insecurity, unemployment and housing – are likely to be key issues on which to focus in order to strengthen the impact of future interventions.

The findings of phase 2 of our research show that a novel, complex, socio-economic intervention was acceptable, feasible, reduced catastrophic costs, and increased TB preventive therapy uptake, confirmed TB cure and treatment success. Informed by these findings, the socio-economic intervention has been further refined in order to assess its impact on community TB control during CRESIPT.

Conclusions

In impoverished shantytowns of Callao, Peru, TB remains a social disease; despite TB treatment being ostensibly free, having TB disease was expensive for impoverished TB patients. The new definition of catastrophic costs created during the phase 1 of this research demonstrated that such costs are clinically relevant because they are associated with greater likelihood of adverse TB outcome. Indeed, catastrophic costs explained as many adverse outcomes as MDR TB. The novel catastrophic costs threshold defined by this research has since been endorsed by the WHO and become part of global TB control policy; informing implementation of the TB Patient Costs tool, which is being piloted in sentinel sites for potential scale-up from 2015 onwards.

Through multi-sectoral collaboration and supported by evidence from a systematic review, we designed a novel TB-specific socio-economic intervention to improve access to preventive therapy, increase TB cure and mitigate catastrophic costs. The intervention was refined to better meet patient and household needs during implementation through community participation, engagement and acceptability feedback, and subsequently proved to be feasible, acceptable, reduced TB-affected households’ catastrophic costs and improved TB care and prevention measures in a challenging, impoverished setting. This research emphasises the need for larger-scale integrated socio-economic interventions to improve TB control and also other health outcomes. In light of our findings and in conjunction with key stakeholders of the WHO and the World Bank, we have developed the protocol of the larger scale, adequately powered CRESIPT study, which will evaluate the impact of the intervention on TB prevalence and control in the study setting.

Despite the positive findings of this research, the impact of the socio-economic intervention may have been limited by the modest defraying of TB-related and catastrophic costs achieved through conditional cash transfers. Such a modest yet significant impact means that, in its current form, the intervention may be unlikely to markedly decrease community rates of incident and prevalent TB during the larger-scale CRESIPT project. Therefore, through liaison with international policymakers in the WHO's Task Force on Catastrophic Costs and Task Force on Social Protection, the intervention has been refined for implementation during the CRESIPT study. Refinements include increasing the frequency and amounts of conditional cash transfers in order to fully mitigate catastrophic costs, provide conditional cash transfers for individual members of the TB-affected household (including monthly transfers to individual household contacts for adherence to preventive therapy) and strengthen the highly valued social support provided by the intervention – especially for high-risk patients such as the homeless, those with drug addiction and those with MDR TB. In this way, the IFHAD team hopes to optimise the CRESIPT project's impact on TB-related costs mitigation, to enhance socio-economic support and, hence, improve TB control.

This research characterised the social determinants of TB, including TB-related catastrophic costs, in Peruvian shantytowns and subsequently created, implemented and refined an innovative TB-specific socio-economic intervention to mitigate catastrophic costs and support TB-affected households. The intervention is now ready for further impact assessment at a community level. The findings of CRESIPT, an extension of this research, will aim to assist TB control programmes to effectively implement the recent – yet 150 years overdue – global policy change of providing socio-economic support to control TB.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Raviglione M. Krech R. Tuberculosis: Still a social disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:6–8. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhargava A. Pai M. Bhargava M. Marais BJ. Menzies D. Can social interventions prevent tuberculosis? The Papwroth experiment (1918–1943) revisited. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:332–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssens J. Rieder H. An ecological analysis of incidence of tuberculosis and per capita gross domestic product. Eur Respir J. 2006;32:1415–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00078708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao VB. Pelly TF. Gilman RH, et al. Zinc cream and reliability of tuberculosis skin testing. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1101–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.070227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingfield T. Schumacher SG. Sandhu G, et al. The seasonality of tuberculosis, sunlight, vitamin d, and household crowding. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:774–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holtgrave D. Crosby RA. Social determinants of tuberculosis case rates in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2004:26L159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dye C. Lönnroth K. Jaramillo E. Williams B. Raviglione M. Trends in tuberculosis incidence and their determinants in 134 countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:683–91. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lönnroth K. Jaramillo E. Williams BG. Dye C. Raviglione M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laokri S. Dramaix-Wilmet M. Kassa F. Anagonou S. Dujardin B. Assessing the economic burden of illness for tuberculosis patients in Benin: determinants and consequences of catastrophic health expenditures and inequities. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:1249–58. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wingfield T. Boccia D. Tovar M, et al. Defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multi-drug resistance: a prospective cohort study, Peru. PLoS Med. 2014;11(11):e1001675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ukwaja KN. Modebe O. Igwenyi C. Alobu I. The economic burden of tuberculosis care for patients and households in Africa: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:733–9. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Sustainable health financing structures and universal coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2011. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_R9-en.pdf. [Accessed 11 August 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Agenda of the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_1Rev1-en.pdf?ua=1. [Accessed 11, August 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha C. Montoya R. Zevallos K, et al. The Innovative Socio-economic Interventions Against Tuberculosis (ISIAT) project: an operational assessment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(Suppl 2):S50–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uplekar M. Weil D. Lonnroth K, et al. WHO’s new end TB strategy. Lancet. 2015;385:1799–801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutge EE. Wiysonge CS. Knight SE. Volmink J. Material incentives and enablers in the management of tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1):CD007952. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007952.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutge E. Lewin S. Volmink J. Friedman I. Lombard C. Economic support to improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:154. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyszewianski L. Families with catastrophic health care expenditures. Health Serv Res. 1986;21:617–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajeswari R. Muniyandi M. Balasubramanian R. Narayanan PR. Perceptions of tuberculosis patients about their physical, mental and social well-being: a field report from south India. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1845–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanimura T. Jaramillo E. Weil D. Raviglione M. Lönnroth K. Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1763–75. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00193413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mauch V. Bonsu F. Gyapong M, et al. Free tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment are not enough: patient cost evidence from three continents. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:381–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solar O. Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell S. The economic burden of illness for households in developing countries: a review of studies focusing on malaria, tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:147–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raviglione MC. Ditiu L. Setting new targets in the fight against tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:263. doi: 10.1038/nm.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laokri S. Weil O. Drabo KM, et al. Removal of user fees no guarantee of universal health coverage: observations from Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:277–82. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.110015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauch V. Woods N. Kirubi B, et al. Assessing access barriers to tuberculosis care with the tool to Estimate Patients’ Costs: pilot results from two districts in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitehead M. Dahlgren G. Concepts and principles for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up part 1. Copenhagen: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauerborn R. Adams A. Hien M. Household strategies to cope with the economic costs of illness. Soc Sci Med. 199;43:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peabody JW. Shimkhada R. Tan C. Luck J. The burden of disease, economic costs and clinical consequences of tuberculosis in the Philippines. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:347–53. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wingfield T. Boccia D. Tovar MA, et al. Designing and implementing a socioeconomic intervention to enhance TB control: operational evidence from the CRESIPT project in Peru. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:810. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma SK. Sharma A. Kadhiravan T. Tharyan P. Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB. Evid Based Child Health. 2014;9:168–294. doi: 10.1002/ebch.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marais BJ. van Zyl S. Schaaf HS, et al. Adherence to isoniazid preventive chemotherapy: a prospective community based study. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:762–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.097220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malotte CK. Hollingshead JR. Larro M. Incentives vs outreach workers for latent tuberculosis treatment in drug users. Am J Prev Med. 2001:20103–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tulsky JP. Hahn JA. Long HL, et al. Can the poor adhere? Incentives for adherence to TB prevention in homeless adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tulsky JP. Pilote L. Hahn JA, et al. Adherence to Isoniazid Prophylaxis in the Homeless. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:697–702. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaisson RE. Keruly JC. McAvinue S. Gallant JE Moore RD. Effects of an incentive and education program on return rates for PPD test reading in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:455–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bock NN. Sales R. Rogers T. Devoe B. A spoonful of sugar…: improving adherence to tuberculosis treatment using financial incentives. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:96–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gialafos E. Rapti A. Kouranos V, et al. Detection of right ventricular dysfunction by tissue Doppler imaging in asymptomatic patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:212–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giuffrida A. Torgerson DJ. Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. BMJ. 1997;315:703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davidson H. Schluger NW. Feldman PH, et al. The effects of increasing incentives on adherence to tuberculosis directly observed therapy SUMMARY. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:860–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ailinger RL. Martyn D. Lasus H. Lima Garcia N. The effect of a cultural intervention on adherence to latent tuberculosis infection therapy in Latino immigrants. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27:115–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alcabes P. Vossenas P. Cohen R, et al. Compliance with isoniazid prophylaxis in jail. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1194–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.M'Imunya JM. Kredo T. Volmink K. Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD006591. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006591.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jr Horsburgh CR. Goldberg S. Bethel J, et al. Latent TB infection treatment acceptance and completion in the United States and Canada. Chest. 2010:137401–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirsch-Moverman Y. Colson PW. Bethel J. Franks J. Can a peer-based intervention impact adherence to the treatment of latent tuberculous infection? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:1178–85. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaisson RE. Barnes GL. Hackman J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of interventions to improve adherence to isoniazid therapy to prevent tuberculosis in injection drug users. Am J Med. 2001;110:610–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00695-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kominski GF. Varon SF. Morisky DE, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of adolescent compliance with treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: results from a randomized trial. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morisky DE. Malotte CK. Ebin V, et al. Behavioral Interventions for the Control of Tuberculosis Among Adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:568–74. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hovell MF. Sipan CL. Blumberg EJ, et al. Increasing Latino adolescents’ adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: a controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1871–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Q. Abba K. Alejandria MM, et al. Reminder systems and late patient tracers in the diagnosis and management of tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(10):CD006594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006594.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.United Nations Research Institute for Social Development Combating poverty and inequality: structural change, social policy and politics. Geneva: UNRISD; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chatham House Social protection interventions for tuberculosis control: the impact, the evidence, and the wat forward. Meeting summary. London: Chatham House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boccia D. Hargreaves J. Lönnroth K, et al. Cash transfer and microfinance interventions for tuberculosis control: review of the impact evidence and policy implications. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(Suppl 2):S37–49. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lagard M. Haines A. Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD008137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evans DB. Elovainio R. Humphreys G. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNAIDS expanded business case: enhancing social protection. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Social Protection Floor Advisory Group Social protection floor of a fair and inclusive globalization. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doetinchem O. Xu K. Carrin G. Conditional cash transfers: what’s in it for health? Technical briefs for policy-makers No 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grede N. Claros JM. de Pee S. Bloem M. Is there a need to mitigate the social and financial consequences of tuberculosis at the individual and household level? AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 5):S542–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volmink J. Garner P. Interventions for promoting adherence to tuberculosis management. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000010. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirsch-Moverman Y. Daftary A. Franks J. Colson PW. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1235–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malotte CK. Rhodes F. Mais KE. Tuberculosis screening and compliance with return for skin test reading among active drug users. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:792–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malotte CK. Hollingshead JR. Rhodes F. Monetary versus nonmonetary incentives for TB skin test reading among drug users. Am J Prev Med. 199;16:182–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White MC. Tulsky JP. Reilly P, et al. A clinical trial of a financial incentive to go to the tuberculosis clinic for isoniazid after release from jail. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Craig P. Dieppe P. Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adato M. Hoddinott J. Social protection: opportunities for Africa. IFPRI policy brief 5. Washington, DC: IFPRI. 2008.

- 69.Wingfield T. Designing and implementing a social protection intervention to enhance TB control: operational evidence from the CRESIPT project, Lima, Peru. Barcelona: 45th Union World Lung Health Conference; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Westerlund EE. Tovar MA. Lönnermark E. Montoya R. Evans CA. Tuberculosis-related knowledge is associated with patient outcomes in shantytown residents; results from a cohort study, Peru. J Infect. 2015;71:347–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rospigliosi M. Norma Técnica para el control de la Tuberculosis, Peru, 2013. National TB Programme Peruvian Ministry of Health,: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization Global tuberculosis report 2015. 20th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis – 2013 revision. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wingfield T. Tovar M. Huff D, et al. The CRESIPT project: community feedback and practical challenges of conditional cash transfers for TB-affected households in Peru [abstract] Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S61–2. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wingfield T. Boccia D. Tovar M, et al. Defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multi-drug resistance: a prospective cohort study, Peru. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.LoBue PA. Moser KS. Use of Isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection in a public health clinic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:443–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-390OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Diaz A. Diez M. Bleda MJ, et al. Eligibility for and outcome of treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in a cohort of HIV-infected people in Spain. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:267. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pettit AC. Bethel J. Hirsch-Moverman Y. Colson PW. Sterling TR. Female sex and discontinuation of isoniazid due to adverse effects during the treatment of latent tuberculosis. J Infect. 2013;67:424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wobeser W. To T. Hoeppner VH. The outcome of chemoprophylaxis on tuberculosis prevention in the Canadian Plains Indian. Clin Invest Med. 1989;12:149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garie KT. Yassin MA. Cuevas LE. Lack of adherence to isoniazid chemoprophylaxis in children in contact with adults with tuberculosis in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kan B. Kalin M. Bruchfeld J. Completing treatment for latent tuberculosis : patient background matters. In J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;17:597–602. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parsyan AE. Saukkonen J. Barry MA. Sharnprapai S. Horsburgh CR. Predictors of failure to complete treatment for latent tuberculosis infection. J Infect. 2007;54:262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hovell M. Blumberg E. Gil-Trejo L, et al. Predictors of adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection in high-risk Latino adolescents: a behavioral epidemiological analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1789–96. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang SH. Eitzman SR. Nahid P. Finelli MLU. Factors associated with failure to complete isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bethel J. Colson PW. Franks J. Predictors of latent tuberculosis infection treatment completion in the United States: an inner city experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1104–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhanot N. Haran M. Lodha A, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards self-treatment of latent tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;16:169–71. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heise L. Lutz B. Ranganathan M. Watts C. Cash transfers for HIV prevention: considering their potential. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18615. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]