Abstract

Introduction:

Canadians are living longer than before, and a large proportion of them are living with obesity. The present study sought to describe how older participants in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) who are living with obesity are aging, through an examination of measures of social, functional and mental well-being.

Methods:

We used data from the first wave of the CLSA for people aged 55 to 85 years in this study. We used descriptive statistics to describe characteristics of this population and adjusted generalized logistic models to assess measures of social, functional and mental well-being among obese participants (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) relative to non-obese participants. Findings are presented separately for females and males.

Results:

More than half of the participants reported living with a low personal income (less than $50 000); females were particularly affected. Less than half of the participants were obese; those who were had higher odds of multimorbidity than those who were not living with obesity (among those aged 55–64 years: odds ratio [OR] 2.7, 95% CI: 2.0–3.5 males; OR 2.8, 95% CI: 2.2–2.5 females). Low social participation was associated with obesity among older female participants, but not males. Physical functioning issues and impairments in activities of daily living were strongly associated with obesity for both females and males. While happiness and life satisfaction were not associated with obesity status, older females living with obesity reported negative impressions of whether their aging was healthy.

Conclusion:

The odds of multimorbidity were higher among participants who were obese, relative to those who were not. Obese female participants tended to have a negative perception of whether they were aging healthily and had lower odds of involvement in social activities, while both sexes reported impairments in functional health. The associations we observed, independent of multimorbidity in older age, highlight areas where healthy aging initiatives may be merited.

Keywords: obesity, healthy aging, mental health, social participation, multimorbidity, happiness

Highlights

Participants of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging reported high levels of involvement in social activities, happiness, life satisfaction and perceived healthy aging.

The odds of multimorbidity were higher among participants who were obese relative to those who were not.

Involvement in social activities was reduced among older female participants living with obesity.

Impairments in functional health were reported more often by participants of both sexes living with obesity.

Older female participants living with obesity had lower odds of reporting healthy aging than older females who were not living with obesity.

Introduction

Canadians are living longer than in previous generations: the proportion of Canadians aged 65 years and older is expected to be 1 in 5 by 2024.1 Healthy aging constitutes more than just longevity, however; an individual’s quality of life (QOL) has a bearing on the years spent living in good health. So, while average Canadians may live longer, they might not necessarily be living well.2 The majority of seniors in Canada are overweight or obese,3 the latter being a known risk factor for a number of chronic conditions4,5 and a factor that can exacerbate age-related declines in physical function and frailty.6 Furthermore, even though perceived weight does not always agree with actual weight, the former has been associated with measures of self-rated health and life satisfaction that vary based on sex.7 Therefore, understanding the role that obesity may play in successful aging among older Canadians is important.

There is, however, an obesity paradox among the elderly: high body mass index (BMI) appears to provide a survival advantage and have a lower association with mortality, while low BMI is often associated with higher mortality relative to normal weight.8 The risks of excess weight among the elderly are complex and there are added considerations such as fat redistribution with age, competing mortalities, and risks associated with weight change that all contribute to the unique perspective on obesity treatment and prevention for this age group.9 The clinical definition of obesity is based on BMI, but there are other metrics of excess weight that may be more applicable to this age group. Metrics that better reflect fat distribution, such as waist circumference, may be able to provide an indication of health risk where BMI cannot.10 In regard to healthy aging, weight management in the elderly is geared towards improving physical function (minimizing muscle and bone loss) and health-related QOL.6

While there is no uniform definition for successful aging, it can be interpreted as maintaining physical, social and mental well-being with age.11 QOL in older individuals is largely determined by these factors,12 and by the ability to maintain autonomy and independence.12 Fewer chronic conditions, strong social supports, high independent functioning and life satisfaction are among the many indicators of successful aging.11,13-15 Within this holistic understanding, social, functional and mental well-being, in combination with fewer chronic conditions and lower levels of mental illness, can be examined together to provide an objective indication of successful aging.

Recent estimates suggest that roughly 15% of Canadians aged 20 years and older are living with two or more chronic diseases (multimorbidity),16 and that these rates increase with age.17 Accordingly, there is growing interest in research on attitudes in later life that contribute to living well.18 Current trends also suggest that obesity and its related illnesses will persist as the “baby boomer” population approaches retirement.19,20 Given this trend, it is prudent to better understand the role obesity may play in successful aging in Canada. Consequently, this study aimed to profile indicators of social, functional and mental health among older Canadians living with obesity, in spite of their multiple chronic conditions.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted using crosssectional data from the first wave of the Tracking Component of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Participants (n = 21 241) were recruited (1) from Statistics Canada’s Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)—Healthy Aging focus survey (n = 3923); (2) the provincial health care registration databases (n = 3810); and (3) through random digit dialling (n = 13 508). All participants were asked survey questions using the computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) technique between 2010 and 2014. The sampling frames excluded residents of the three Canadian territories, persons living on federal First Nations Reserves, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, individuals living in long-term care institutions, and individuals unable to communicate in English or French. A detailed background and methodology on CLSA are available elsewhere.21 The study population was restricted to individuals between the ages of 55 and 85 years (N = 15 345).

Variables

Socioeconomic characteristics

We ascertained annual individual income levels based on self-reported total personal income from all sources and recoded them as a binary variable (< $50 000 vs. ≥ $50 000). We derived home residence status, which was used as a subjective measure of financial well-being, from a combination of the dwelling within which the individual resided, and their ownership status. Individuals who lived in seniors’ housing, old-age facilities and hotels were identified as not residing in their own home, and individuals who lived in other independent venues (house or apartment) but who also indicated that they did not own their residence were also considered not to live in their own home. Individuals who responded that they lived in a house or apartment and that they owned their home were identified as living in their own home.

Behavioural characteristics

Current smoking status was identified based on self-report (current smoker vs. current nonsmoker [former smoker or never smoker]), as was level of usual alcohol consumption (≥ 4 alcoholic beverages per week vs. < 4).

Health characteristics

We derived BMI from self-reported height and weight and calculated it as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Obesity was identified as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and nonobesity (including normal weight and overweight) was identified as BMI < 30 kg/m2.22 We derived multimorbidity from selfreported diagnosis with two or more of the following conditions23,24: arthritis, respiratory conditions (asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), diabetes, heart disease (including angina, heart attack, and peripheral vascular disease), stroke (including cerebrovascular event and transient ischemic attack), neurological conditions (Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease), cancer, or mental health disorders (mood or anxiety). Respondents were identified with these conditions if they responded yes to the respective question of whether they had ever been told by a doctor that they had the condition.

Social health

Participants were asked how often in the past 12 months (at least once a day, at least once a week, at least once a month, at least once a year, never) they participated in eight different activities: (1) family- or friendship-based activities outside the household; (2) church or religious activities; (3) sports or physical activities that you do with other people; (4) educational and cultural activities involving other people; (5) service club or fraternal organization activities; (6) neighbourhood, community or professional association activities; (7) volunteer or charity work; or (8) other recreational activities involving other people. Based on their responses, participation in community and social activities was recoded as participating in community or social activities at least once a week versus less frequently. Questions were taken from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey for these measures, which have been shown to be valid and reliable in older females.25

Functional health

We determined physical functioning based on responses to 14 questions. For each of the 14 scenarios asked, such as whether an individual experienced physical difficulty extending an arm above their head, we coded individuals as having functional limitations if they experienced limitations with 3 or more of the proposed scenarios. Impairments to activities of daily living were recoded based on responses using the Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Assessment scale,26 which has been validated previously.27 Ordinal response options were recoded as either “no impairment” or “mild to total impairment.”

Mental health and well-being

We determined mental health status based on self-report of a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosed by a physician. Various measures were used for mental wellbeing. We identified happiness as feeling happy 3 or more days per week versus fewer. While this measure is not a substitute for specific mental health assessment, it has been validated as a useful one to measure general mental health.28 Selfreported measures of happiness have been shown to associate with lower mortality, which may be mediated by physical activity and comorbidity, in the elderly.29 Life satisfaction was derived from reports of feeling slightly satisfied or better with life versus neutral or dissatisfied. These measures (self-rated mental health and selfrated healthy aging) were each coded as binary variables based on self-report responses of “fair” or “poor” versus “good,” “very good” or “excellent,” respectively.

Analysis

We used descriptive analyses to examine socioeconomic, behavioural and health characteristics among older Canadian participants (restricted to those aged 55 to 85 years). We used chi-square analyses to compare characteristics across age-groups, and by sex. Logistic regression models were constructed to examine the association between obesity (compared to nonobesity) and multimorbidity, functional health, social health, mental health and mental well-being. We tested potential confounders individually for inclusion in a logistic regression model assessing the odds of multimorbidity based on obesity status, and the level of significance was set at p-value < .20. Accordingly, we used the following confounding variables: income level, alcohol consumption and current smoking behaviour. Education level and marital status were also tested but were not found to be significant. We included multimorbidity in the models to control for its association with obesity. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs are presented. The overall response rate was 10% for the CLSA–Tracking Component sample, and although trimmed sampling weights were used to account for the complex and multiple sampling frames in the CLSA, results are described for the CLSA sample and not generalizable to the Canadian population.30

Results

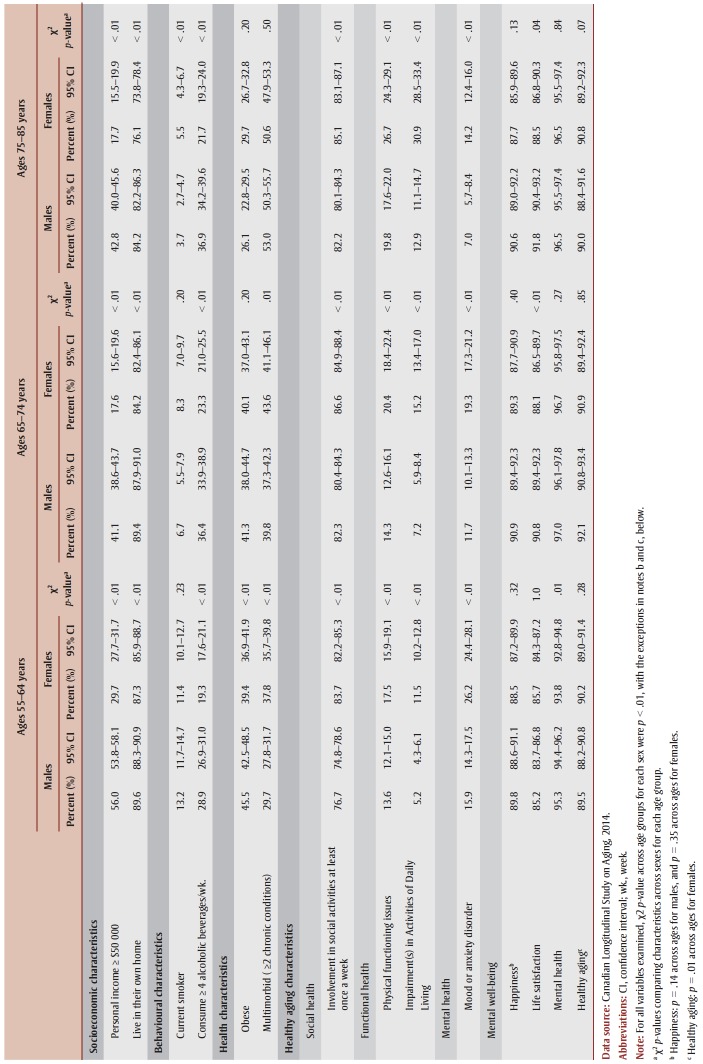

With each successive age group, the number of individuals represented through weighting techniques diminished by a factor of two (weighted N55-64y = 4 090 454; weighted N65-74y = 2 599 404; and weighted N75-85y = 1 664 872). The prevalence and distribution of socioeconomic, behavioural and health characteristics are described in Table 1. Roughly half of male participants aged 55 to 64 years had a personal income of greater than $50 000, with this value decreasing significantly in older age groups. Less than a third of female participants aged 55 to 64 years had a personal income greater than $50 000, significantly fewer than the proportion of males. We observed significant decreases in older age groups. We observed significant differences in residence ownership between the sexes, as well as across age groups, with proportions showing that many older participants lived in their own home.

Table 1. Socioeconomic, behavioural and health characteristics of older respondents to the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2014.

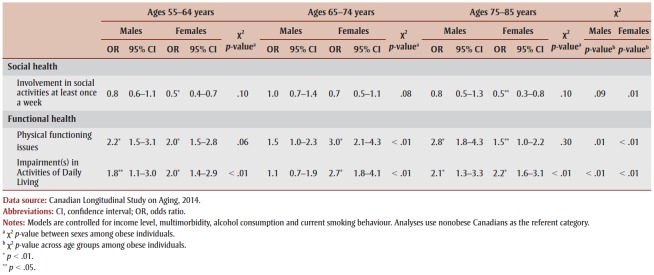

With respect to health, the proportion of current smokers was lower in older age groups for each sex. While smoking behaviours were not significantly different between the sexes at age 55 to 64 years, more females than males aged 75 to 85 years reported smoking (p < .01). The consumption of 4 or more alcoholic beverages per week differed significantly between the sexes, and also decreased significantly with increasing age groups. Obesity was significantly higher among males and decreased with age, until age 75 to 85, where more females lived with obesity than males, despite their own age-related decreases. Finally, significantly more females than males reported having multimorbidity at ages 55 to 64, with differences disappearing by ages 75 to 85 years (Table 1). Across all age groups, and for both sexes, multimorbidity was strongly associated with obesity (Table 2). We observed differences between the sexes in younger age groups (p < .01), but not among those aged 75 to 85 years (p = .8).

Table 2. Odds ratio of multimorbidity among older obese respondents to the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2014, by age group and sex.

|

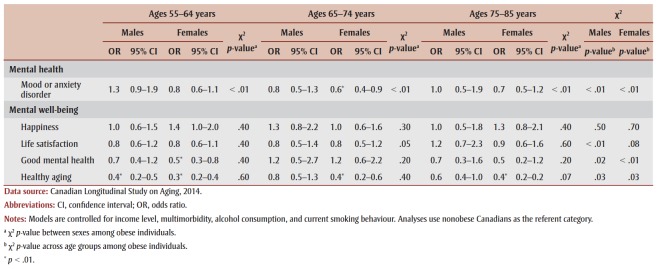

Reduced social participation among male participants was not associated with obesity. However, among female participants aged 55 to 64 and 75 to 85, it was (OR 0.5, 95% CI: 0.4–0.7, and OR 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8, respectively; Table 3). While social participation among individuals living with obesity did not vary significantly between the sexes, there were significant differences across age groups for females (p < .01). Reduced physical functioning was strongly associated with obesity for both males and females, with differences between the sexes being significant only among those aged 65 to 74 years old. The strength of this association between reduced physical functioning and obesity increased with age for both sexes. Similarly, impairments in activities of daily life were significantly associated with obesity for both sexes, with the strength of association increasing with age. The difference between sexes was significant across all age group, with females living with obesity reporting more impairments than males living with obesity.

Table 3. Odds ratios for indicators of social and functional health among older obese respondents to the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2014, by age group and sex.

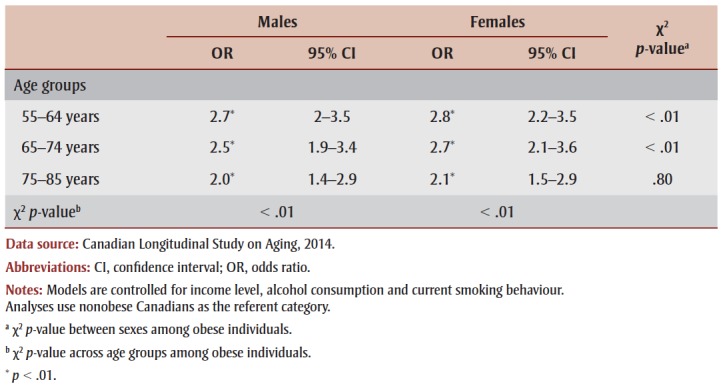

The odds of having a mood or anxiety disorder among those who were obese, relative to those who were not, was significant among females aged 65 to 74 years (OR 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9); differences between the sexes and across ages were significant as well (p < .01) (Table 4). Measures of happiness and life satisfaction were not significantly associated with obesity status for either sex or for any age group. Self-reported good mental health, however, was significantly lower among females in the 55 to 64 age group who were living with obesity, but this association of mental health with obesity disappeared in older age groups. Self-reported healthy aging was significantly associated with obesity among older Canadian participants— females in all age groups reported strong negative impressions of their aging. Among males, however, this finding was only observed among those aged 55 to 64 years (OR 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.5).

Table 4. Odds ratios for indicators of mental health and well-being among older obese respondents to the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2014, by age group and sex.

Discussion

Canadians are enjoying a longer life span than ever before, with recent population estimates showing that the number of Canadians aged 65 years and older outnumber those 14 years and below.1 More than half of older Canadians are living with a low personal income, and females are disproportionately affected.31 While studies have suggested that poor financial health is linked with disease,32 we observed that CLSA participants had strong subjective financial well-being. We also found that many drank 4 or more drinks per week in their older age, although the prevalence of current smokers decreased with increasing age. The former finding is not necessarily troubling, since regular alcohol consumption has been associated with increasing QOL and mood,33 although it is still linked to chronic diseases such as cancer.34

The burden of multimorbidity in seniors is well recognized17,35,36 and is a combination of physical and mental health that impacts QOL37,38 and often results in greater selfcare needs.38 Assessing the impact of obesity on older Canadians would require accounting for the significant prevalence of multimorbidity among older individuals. Although declines in obesity were observed with increasing age in our study, this may reflect mortality patterns. It may also reflect frailty in the aging population, which is a syndrome linked with declines in health and function that include unintentional weight loss, muscle loss or weakness and fatigue.39 So, while BMI may be treated as an independent state, it can also be both a symptom and risk factor associated with disease.

Given these complex associations, our study describes how older participants of the CLSA study were aging in spite of their chronic conditions, lifestyle behaviours or socioeconomic circumstances. Subjective well-being consisted of three different aspects: evaluative (life satisfaction), hedonic (feelings, including happiness) and eudemonic (sense of purpose) well-being. These measures are thought to capture what matters to individuals and have been shown to be relevant to health and QOL as people age.40,41 We observed that social participation, which is a eudemonic construct, is diminished among older female participants living with obesity, but not males. The decreasing trend of social participation with increasing age among female participants living with obesity was significant. A previous study found that social participation was not associated with BMI, but unlike this study, they controlled for depression and selfesteem. 42 Given the strong ties of selfesteem to social participation, it is possible that our findings reflect feelings of lowered self-esteem among older females living with obesity. Social participation and support are important to good physical health, more so than positive health behaviours, even into late adulthood (90 to 97 years).43 Obesity has been associated with lowered physical functioning,6 although women living with obesity experience fewer such impairments than men. The strong positive associations of physical limitations with obesity in this study align with previous research suggesting that obesity and low physical activity predicts the onset of mobility limitations in older adults.44 While we were unable to control for levels of physical activity in our analyses, our finding of an association between obesity and physical function might still be influenced by physical activity. One study has found that those older adults who were moderately to vigorously physically active had reduced risks of mobility limitation relative to those who were not active, and that individuals who maintained or took up physical activity also saw mobility benefits when compared to those who did not.45 Similarly, the finding that impairments of daily living increased with age, and were stronger among females, highlights an at-risk demographic that may benefit from healthy aging programs.

Measures of mental health and well-being can vary by age and sex.45,46 Anxiety in older age has been shown to have a bidirectional relationship with cognition and with decreases in executive functioning. 47 Measures of mental well-being included those that were evaluative and hedonic. We observed no significant associations of these constructs with obesity in older age, although when we examined these attributes across age groups, chisquare estimates suggested that age is related to life satisfaction among males. Life satisfaction has been previously shown to associate with mortality among men, but not women48. Furthermore, these associations were suggested to be partially mediated through adverse health behaviours.48 So, while adjusting for covariates may have dissipated associations of obesity with life satisfaction, as observed with ORs, the chi-square trends suggest an opportunity to study this evaluative construct among older males. The low perception of good mental health among older females is noteworthy, although this improves with age. Finally, in the context of how retaining a positive outlook can support living well into old age,18 we found that older participants living with obesity self-identified as not aging with good health. This finding was significant for females in all the age groups examined, and for males in the group aged 55 to 64 years. A negative association of obesity on life satisfaction has been described previously as well, and although this finding was significant among both sexes, Wadsworth et al. found the association to be stronger among females than among males.49

Strengths and limitations

The use of a large national survey to examine detailed characteristics of aging is one of the main strengths of this study. However, some limitations must be considered in interpreting our findings. First, BMI was derived based on self-reported measures of height and weight, which may be subject to respondent bias, with some data indicating that misreporting is greatest in the oldest age group.50 Because of these possible biases, it is difficult to gauge their impact in the context of the multivariable models discussed. Second, given the current literature regarding frailty in older age, it is unclear whether BMI is the most appropriate measurement of obesity or excess body fat for older individuals. Third, the analysis conducted in this study is limited by the information available in the survey. Thus, there may be other important factors that were not included, such as physical activity, nutrition and other environmental factors. The lack of information on physical activity, sedentary time and general time use constrains the interpretation of the obesity–health relationship, particularly given the known associations of physical activity with measures of health in old age.45 Fourth, although sample weights are generally applied so as to permit an estimation of statistics representative to the Canadian population, the first wave of the CLSA had a low response rate. Therefore, while we have applied sampling weights in our analyses, we describe our results in relation to CLSA participants, and these might not be generalizable to the Canadian population. Finally, we are aware that not all self-reported measures used in this analysis have been validated, such as happiness and healthy aging; therefore, interpretations should be made with caution.

Conclusion

This study provides a baseline analysis of healthy aging among older Canadian CLSA participants living with obesity that may be continued with successive cycles of the CLSA. The finding that these older Canadians’ social and functional health profiles were associated with their obesity, even though other measures of well-being mostly were not, is also concerning as we transition to an era in which healthy aging is becoming a growing concern. These profiles should help to assist efforts geared toward promoting healthy aging for all by providing a picture of how social, functional and mental well-being is impacted by obesity in this age demographic.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors were involved in the conceptualization of this study, the interpretation of findings, and in the approval of the final manuscript. PP and DR analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): The Daily: Canada’s population estimates: age and sex, July 1, 2015 (Internet) Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/150929/dq150929b-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Health-adjusted life expectancy in Canada: 2012 report by the Public Health Agency of Canada. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Obesity in Canadian adults: it’s about more than just weight (Table 1) (Internet) Available from: https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/datalab/adult-obesity-blog-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- Faeh D, Braun J, Tarnutzer S, et al, et al. Obesity but not overweight is asso¬ciated with increased mortality risk. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26((8)):647–55. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjepkema M, et al. Adult obesity. Health Rep. 2006;17((3)):9–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, et al. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res. 2005;13((11)):1849–63. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman KM, Hopman WM, Rosenberg MW, et al. Self-rated health and life satis¬faction among Canadian adults: asso¬ciations of perceived weight status versus BMI. Qual Life Res. 2013;22((10)):2693–705. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulos A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Sharma AM, et al, et al. The obesity para¬dox in the elderly: potential mecha¬nisms and clinical implications. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25((4)):643–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni M, Mazzali G, Zoico E, et al, et al. Health consequences of obesity in the elderly: a review of four unresol¬ved questions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29((9)):1011–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R, et al. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004:379–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan EA, Larson EB, et al. “Successful aging”–where next. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50((7)):1306–08. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.t01-1-50324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio E, zaro A, nchez A, et al. Social participation and indepen¬dence in activities of daily living: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr (Internet) doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-26. Available from: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL, et al. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37((4)):433–40. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos NP, Havens B, et al. Predictors of suc¬cessful aging: a twelve-year study of Manitoba elderly. Am J Public Health. 1991;81((1)):63–68. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, et al, et al. Successful aging: predictors and associated activities. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144((2)):135–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators data tool, 2017 Edition (Internet) Available from: https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ccdi-imcc/data-tool/ [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KC, Rao DP, Bennett TL, et al, et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease multimorbidity and associated determinants in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2015;35((6)):87–94. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.35.6.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann HP, Grebe H, et al. “Senior coolness”: living well as an attitude in later life. J Aging Stud. 2014:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Colditz GA, Kuntz KM, et al. Forecasting the obesity epidemic in the aging U.S. Forecasting the obesity epidemic in the aging U.S. population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15((11)):2855–65. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancej C, Jayabalasingham B, Wall RW, et al, et al. Evidence Brief—Trends and projections of obesity among Canadians. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2015;35((7)):109–12. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.35.7.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina PS, Wolfson C, Kirkland SA, et al, et al. The Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA) Can J Aging. 2009:221–9. doi: 10.1017/S0714980809990055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appropriate body-mass index for Asian popula¬tions and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363((9403):157-63. Erratum in Lancet. 2004;363(9412)):157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt MT, Roberts KC, Bennett TL, et al, et al. Monitoring chronic diseases in Canada: the Chronic Disease Indicator Framework. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34((Suppl 1)):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technical meeting: measurement of multimor¬bidity for chronic disease surveillance in Canada (unpublished summary report); 2012. Multimorbidity Technical Working Group, Chronic Disease Surveillance and Monitoring Division, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, et al, et al. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65((10)):1107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA, et al. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol. 1981;36((4)):428–34. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble SE, Fisher AG, et al. The dimensio¬nality and validity of the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale. J Outcome Meas. 1998;2((1)):4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawani FN, Gilmour H, et al. Validation of self-rated mental health. Health Rep. 2010;21((3)):61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans TA, Geleijnse JM, Zitman FG, et al, et al. Effects of happiness on all-cause mortality during 15 years of follow-up: the Arnhem Elderly Study. J Happiness Stud. 2008;11((1)):113–24. [Google Scholar]

- CLSA. Hamilton(ON): 2014. CLSA Sampling Weights -Technical Document: Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Labour Congress. Ottawa(ON): Did you know senior women are twice as likely to live in poverty as men. Available from: http://canadianlabour.ca/issues-research/did-you-know-senior-women-are-twice-likely-live-poverty-men. [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Fenn K, Meadows R, et al. Subjective financial well-being, income and health inequalities in mid and later life in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2014:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AM, Muhlen D, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Regular alcohol consumption is asso-ciated with increasing quality of life and mood in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Maturitas. 2009;62((3)):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-speci¬fic cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;112((3)):580–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akner G, et al. Analysis of multimorbidity in individual elderly nursing home residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49((3)):413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, Wang HX, et al, et al. Patterns of chronic multimorbi¬dity in the elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57((2)):225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, et al, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes (Internet) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-51. Available from: https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1477-7525-2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF, et al. Seniors’ self-reported multimorbidity captured biopsychosocial factors not incorporated into two other data-based morbidity measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62((5)):550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004:255–63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA, et al. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;385((9968)):640–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, et al. Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Zettel-Watson L, Britton M, et al. The impact of obesity on the social participation of older adults. J Gen Psychol. 2008:409–23. doi: 10.3200/GENP.135.4.409-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry KE, Walker EJ, Brown JS, et al, et al. Social engagement and health in younger, older, and oldest-old adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32((1)):51–75. doi: 10.1177/0733464811409034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster A, Patel KV, Visser M, et al. Joint effects of adiposity and physical activity on incident mobility limitation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56((4)):636–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Ebrahim S, Papacosta O, et al, et al. From a postal questionnaire of older men, healthy lifestyle factors reduced the onset of and may have increased recovery from mobility limitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58((8)):831–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra S, Leitsch S, Graber J, et al, et al. Quality of life and psychological health indicators in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64((Suppl 1)):i30–i37. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochim BP, Mueller AE, Segal DL, et al. Late life anxiety is associated with decreased memory and executive functioning in community dwelling older adults. J Anxiety Disord. 2013:567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkanen R, Viinamaki H, et al, et al. Self-reported life satisfaction and 20-year mortality in healthy Finnish adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152((10)):983–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth T, Pendergast PM, et al. Obesity (sometimes) matters: the importance of context in the relationship between obesity and life satisfaction. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55((2)):196–214. doi: 10.1177/0022146514533347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiely F, Hayes K, Perry IJ, et al, et al. Height and weight bias: the influence of time. pone. :e54386–214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054386. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0054386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]