Abstract

Background:

Childhood abuse and neglect, or childhood trauma (CT), has been associated with methamphetamine use, HIV, and depression. This study explored the potential for sleep dysfunction to influence the relationship between CT and depression in methamphetamine using men.

Methods:

A total of N = 347 men were enrolled: 1) HIV-uninfected, non-methamphetamine (MA) using heterosexual and homosexual men (HIV- MA-; n = 148), 2) MA-using MSM living with HIV (HIV + MA +; n = 147) and 3) HIV-uninfected, MA using MSM (HIV- MA +; n = 52). Participants completed measures of demographic characteristics, sleep dysfunction, childhood trauma, and depression.

Results:

Participants were on average 37 years old (SD = 9.65). Half of participants were Hispanic, and 48.1% had a monthly personal income of less than USD$500. Controlling for sleep dysfunction and control variables, the impact of CT on depression decreased significantly, b = 0.203, p < 0.001, and the indirect effect of CT on depression was significant according to a 95% bCI, b = 0.091, bCI (95% CI 0.057, 0.130). That is, sleep dysfunction partially explained the relationship between CT on depression.

Limitations:

Important limitations included the cross-sectional design of the study, and the self-reported measure of sleep.

Conclusions:

Results highlight the use of sleep interventions to prevent and treat depression, and the utility of assessing sleep disturbances in clinical care.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, Sleep, Depression, Childhood maltreatment

1. Introduction

Childhood abuse and neglect, or childhood trauma (CT), has been associated with both substance use and depression (Briere & Elliott, 2003; Ding, Lin, Zhou, Yan, & He, 2014; Edalati & Krank, 2016). Among methamphetamine users, studies report 50.5% of users endorse at least one of eight adverse childhood events, suggesting that childhood adversity may increase susceptibility for substance use (Ding et al., 2014). Childhood abuse and neglect has also been more frequently reported by have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV; MSM rates of methamphetamine use range from 10% to 23%. In addition, a history of childhood physical neglect has been associated with depression, and slower recovery from depression (Briere & Elliott, 2003; Mandelli, Petrelli, & Serretti, 2015; Paterniti, Sterner, Caldwell, & Bisserbe, 2017).

The relation between CT and depression (Briere & Elliott, 2003; Mandelli et al., 2015) may be explained by sleep dysfunction, which includes sleep onset, sleep latency, wake after sleep onset, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency, as CT has been linked to sleep dysfunction (Kajeepeta, Gelaye, Jackson, & Williams, 2015). Sleep dysfunction has also been linked to depressive symptomatology and fatigue (Brostrom, Wahlin, Alehagen, Ulander, & Johansson, 2018), and may result from impaired circadian sleep rhythms arising from posttraumatic stress symptomatology, e.g., hypervigilance (Ugland & Landr∅, 2015). Combined, these findings suggest that CT, depression, and sleep dysfunction may be interrelated. These relations may also be influenced by HIV status or by antiretroviral therapy (ART); among those living with HIV, sleep dysfunction is common; previous research in this population classified 88% as poor sleepers, with 66% reporting less than 7 h of sleep for most nights over the last month and 60% reporting delayed sleep onset latency (Frain, 2017). Methamphetamine use also prevents sleep and some users may sleep for up to 30 h following use (Meth woes outlined in Alamosa County, 2007; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2016), which may exacerbate symptoms associated with sleep dysfunction, particularly among those with an increased vulnerability for sleep disorders.

Early life exposure to traumatic experiences has been identified a risk factor for poor sleep quality in adulthood (Greenfield, Lee, Friedman, & Springer, 2011; Kajeepeta et al., 2015). Developmental frameworks suggest that the impact of childhood experiences on sleep dysfunction in adulthood are mediated by biological processes, such as increased allostatic load due to exposure to repetitive stress. Furthermore, children who have experienced abuse and frequent re-victimization may be unable to develop or maintain healthy sleep schedules and such patterns may continue into adulthood (Anda et al., 2006). In addition, previous studies have shown that childhood experiences increase sleep disturbances by 2.1 (Greenfield et al., 2011). In turn, sleep disturbances predict the onset of depression and are predictor of continued chronic depression (Baglioni et al., 2011).

Given the high rates of CT, depression, and sleep disorders among MSM living with HIV, including those who use methamphetamine, this study sought to examine the role of sleep dysfunction in the association between CT and depression. Consistent with prior research and theory, it was hypothesized that CT and sleep dysfunction would both be associated with depression (Briere & Elliott, 2003; Broström et al., 2017; Krystal, 2012; Mandelli et al., 2015). However, because, to the best of our knowledge, the interrelatedness of these three clusters of symptoms had not been explored in prior research, the mediational effect of sleep dysfunction between CT and depression was tested. It was hypothesized that sleep dysfunction would account for this association. Given the increased risk for sleep dysfunction among people living with HIV and methamphetamine users, whether this mediational effect would differ as a function of HIV status and methamphetamine use was explored. It was anticipated that results from this study could guide the development of interventions to treat depression among those living with HIV and methamphetamine users.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedures

Prior to any study activities, approval was obtained from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Candidates were recruited by convenience sampling from local clinics, hospitals, support groups, drug treatment programs, and by word of mouth in Southeastern Florida. Due to the high rates of methamphetamine use among men in Southeastern Florida, particularly among MSM, recruitment targeted men. Participants were included if they were heterosexual men or MSM, HIV seropositive or negative, having or not having a history of methamphetamine use, and if they were between the ages of 18 and 55. Participants were excluded if they endorsed a history of migraine, seizure, visual impairment, learning disorders, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, current treatment for hepatitis C, or depression, bereavement resulting in a loss of social support in the preceding 3 months. A total of N = 347 men were enrolled: 1) HIV-uninfected, non-methamphetamine (MA) using heterosexual and homosexual men (HIV- MA-; n = 148), 2) MA- using MSM living with HIV (HIV+ MA +; n = 147) and 3) HIV-uninfected, MA using MSM (HIV- MA +; n = 52). All participants were compensated $50 for their time and transportation. Enrolled participants completed pencil-and-paper measures in private study offices. Further detail about the study protocol, including recruitment and procedures, has been previously described (Carrico, Rodriguez, Jones, & Kumar, 2018).

2.2. Measures

Demographic and biopsychosocial characteristics.

Demographic and biopsychosocial questionnaires, including questions regarding MA and polydrug use, were administered by trained Bachelor- or Masters-level research study personnel.

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D requires respondents to report the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week. CES-D scores range from 0 to 60; higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptomatology. In this sample, internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.87).

Childhood Abuse and Neglect.

Trauma and neglect were assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997) a 28-item Likert scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often) assessing emotional abuse (parents wished they had never been born), physical abuse (was kicked, bit, or burned), sexual abuse (was touched in a sexual way), emotional neglect (not listened to or caregivers were unsupportive), physical neglect (was not taken to a doctor), and denial about abuse and neglect in childhood (had a “perfect” childhood). Possible scores for this scale range from 28 to 140, where greater scores indicate a greater frequency or severity of CT. In this sample, reliability was excellent (α = 0.84).

Sleep Dysfunction.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality index (PSQI) was used to assess overall sleep disturbance (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). The PSQI includes seven components of sleep quality: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. In the current study, the PSQI global score was used for analyses. Greater scores on this scale indicated a greater degree of sleep dysfunction (α = 0.59).

Substance Use.

The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), non-patient version (SCID-IV-NP; (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992) was used to assess methamphetamine use. The assessment included the duration and frequency of methamphetamine use, as well as remission from methamphetamine dependence. Among those who reported drug use, an indicator variable was created to differentiate those who were substance dependent versus those who reported recreational methamphetamine use, methamphetamine abuse, and remission from methamphetamine use for a period of 12 months. All participants in the study met criteria for either methamphetamine abuse or dependence, which required participants to have used methamphetamine in the past 12 months. Per DSM-IV criteria, participants were not considered to be in remission if they met reported any methamphetamine use with 12 months of meeting criteria for methamphetamine abuse or dependence.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used to examine the sociodemographic and psychosocial associations with depression. Comparisons were conducted by group (HIV-ΜΑ-, HIV + MA +, HIV-MA +) to describe participant characteristics. Covariates were deemed potential confounders if they were associated with depression at p < 0.10 in bivariate analyses. Subsequently, a series of multiple linear regression models were built with depression as the outcome and the variables identified to be associated with depression in bivariate analyses included as covariates, independent variables. Only variables significant at p < 0.10 in the multivariable model were included in subsequent analyses. Then, a simple mediation model (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) was developed, using depression as the dependent variable, childhood trauma and neglect as the independent variable, and sleep dysfunction as a mediator, while controlling for the variables retained in the reduced multivariable model. A test of mediation was performed using the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes for SPSS (model 4), with 5000 bootstrap samples as suggested by (Hayes, 2009). Results from the test of mediation are reported using Baron and Kenny (1986) classical approach. The presence of an indirect effect was assessed using the absence of zero in the bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (bCI) Hayes (2009). These analyses are appropriate to use in homogenous or heterogenous samples, as sample heterogeneity or homogeneity is not an assumption of ANOVAs, chisquare, or regression analyses (Field, 2009). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v22 for Windows was used to perform analyses, and a cutoff of p < 0.05 level determined statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of participants

Participants were on average 37 years old (SD = 9.65). Half of participants were Hispanic, and 48.1% had a monthly personal income of less than USD$500. Group differences emerged in all sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, such that methamphetamine users and/or methamphetamine users living with HIV were more likely to have low income, to report a history of trauma or neglect, sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms. Detailed between-group comparisons are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Characteristics of Participants (N = 347)

| All Mean(SD) n(%) |

HIV-MA- n = 148 Mean(SD) n(%) |

HIV + MA + n = 147 Mean(SD) n(%) |

HIV-MA + n = 52 Mean(SD) n(%) |

X2/F/t, p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.03 (9.98) | 35.43 (10.59) | 39.87 (8.76) | 33.56 (9.48) | 11.67, < 0.001 |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 65 (18.7%) | 13 (8.8%) | 37 (25.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | |

| Black | 92 (26.5%) | 40 (27.0%) | 40 (27.2%) | 12 (23.1%) | |

| Haitian/Bahamian/Other | 14 (4.0%) | 7 (4.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 3 (5.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 176 (50.7%) | 88 (59.5%) | 66 (44.9%) | 22 (42.3%) | 16.43, 0.002 |

| Monthly Personal Income (USD) | |||||

| Less than $500 | 167 (48.1%) | 48 (32.4%) | 89 (60.5%) | 30 (57.7%) | |

| $500 to $999 | 112 (32.3%) | 47 (31.8%) | 48 (32.7%) | 17 (32.7%) | |

| $1000 and over | 68 (19.6%) | 53 (35.8%) | 10 (6.8%) | 5 (9.6%) | 48.07, < 0.001 |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | 63.81 (16.46) | 53.78 (12.74) | 72.54 (15.50) | 67.90 (12.39) | 69.23, < 0.001 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 7.70 (4.92) | 3.95 (2.41) | 10.73 (4.49) | 9.83 (4.19) | 134.54, < 0.001 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression | 20.83 (12.35) | 10.88 (6.94) | 28.59 (10.05) | 27.25 (10.17) | 162.72, < 0.001 |

Note. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression.

3.2. Bivariate and multivariable associations with depression

In bivariate analyses, older age, White race, lower income, greater CT, sleep dysfunction, and methamphetamine abuse were associated with depression. In a multiple linear regression model, White race, income, CT, sleep dysfunction, and methamphetamine abuse remained statistically significant.

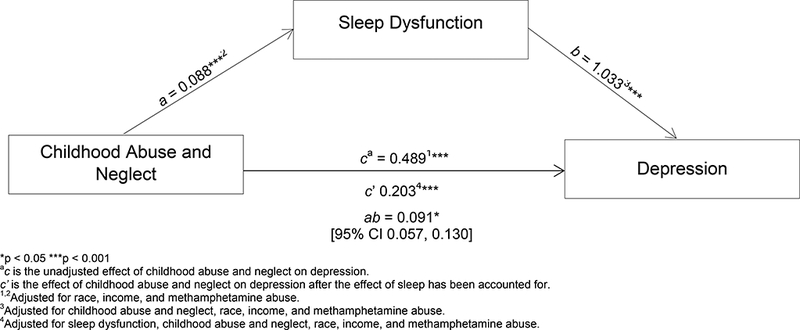

3.3. Mediation model: indirect effect of childhood abuse and neglect on depression through sleep dysfunction

The variables that remained in the reduced multiple regression model (race, income, methamphetamine abuse) were included as covariates in the following analyses testing the potential for sleep dysfunction to mediate the relationship between CT and depression. In the first model, excluding the proposed mediator and after adjusting for these control variables, CT was associated with depression, b = 0.489, p < 0.001. In the second model, CT was associated with sleep dysfunction (b = 0.088, p < 0.001), accounting for the covariates previously listed. In the third model, sleep dysfunction was associated with depression (b = 1.033, p < 0.001) after controlling for CT in addition to the other covariates. After introducing sleep dysfunction as a mediator and the control variables previously described, the effect of CT on depression decreased significantly, b = 0.203, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of CT on depression was statistically significant according to a 95% bCI, b = 0.091, bCI (95% CI 0.057, 0.130). That is, sleep dysfunction partially explained the relationship between CT on depression (see Fig. 1). This mediational effect did not differ as a function of group membership.

Figure 1.

Mediation model: Indirect effect of childhood abuse and neglect on depression through sleep dysfunction.

4. Discussion

This study examined the role of sleep in the relationship between CT and depression. Findings indicated that sleep quality partially accounted for the relationship between CT and depressive symptoms, which was consistent with previous research linking CT with poor sleep quality (Kajeepeta et al., 2015) and sleep disturbances with depressive symptoms (Rumble, White, & Benca, 2015). The unique aspect of this study is the examination of sleep as a mediator of the relationship between CT and depression among men who have sex with men. The current study results provide additional support for previous studies reporting that sleep disturbances, broadly defined, mediate the relationships between traumatic events/traumatic stress and a variety of health outcomes, including depression (Spilsbury, 2009).

Treatment of sleep disturbances presents unique opportunities to also treat depression; treatment for insomnia has been shown to improve mood independent of treatment for depression (Carney et al., 2017; Manber et al., 2008), and may also provide benefits for other aspects of daytime functioning (e.g., memory, impulsivity, attention/ concentration). Sleep disorder treatment may also build skills that increase receptiveness to, and success with, other related psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression) for those who are not ready for treatment for a substance use, mood, or anxiety disorder, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Such patients may also benefit from prior psychoeducational interventions to better understand the potential causal mechanisms between CT, sleep dysfunction, and depression in the context of substance use disorders to gradually increase receptivity towards treatment. Finally, treatment for sleep disorders may be less stigmatizing than treatment for trauma or depressive disorders. Sleep disorders such as insomnia typically respond to treatment more quickly than other psychological disorders (e.g., depression) (Buysse, Rush, & Reynolds, 2017), which may also increase acceptability among gender or ethnic minority populations for whom access to psychological care may be limited due to negative cultural perceptions of psychological treatment (Graham, 2011; McGuive & Miranda, 2008).

4.1. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study’s findings is the use of a broad, subjective, retrospective measure of sleep. The PSQI indicates sleep disturbances across a variety of domains (e.g., sleep medication use, insomnia symptoms, sleep duration), and therefore the nature of the sleep disturbances that mediate the relationship between CT and depression remains unclear. Future research should examine both subjective and objective assessments of sleep, preferably prospectively, in targeted domains related to the current population. Ecological momentary assessments that track daily movement, including sleep patterns, may be useful in overcoming the recall and social biases associated with self-report (Short, Allan, & Schmidt, 2017). Another important limitation was the cross-sectional design of the study, which limits causal interpretation of the findings. Longitudinal studies assessing the mediational effect of sleep dysfunction between CT and depression are needed to determine whether long-term sleep dysfunction may represent a causal mechanism in the relation between CT and depression - such a causal model may test whether sleep dysfunction leads to depression after exposure to traumatic events in childhood. Reasons and motivation for methamphetamine use in this study may have also differed by sexual orientation or HIV status. In previous research among MSM who identified as bisexual or gay, HIV-infected men were more likely to use methamphetamine to cope (Halkitis, Green, & Mourgues, 2005). However, reasons and motivation for use were not assessed in the present study and should be considered in future research. The constructs presented in the present study are also subject to potential measurement invariance by sexual orientation and HIV status; however, measurement invariance does not invalidate measures, although it limits reliable comparisons across groups (Meade & Lautenschlager, 2004). Another limitation was also that urine analysis was not used to confirm self-reported methamphetamine use. In addition, given the heterogeneity of the sample, the generalizability of the present study is limited. Finally, patients were not evaluated to assess current intoxication or abstinence, and the presence of other neuropsychiatric disorders, drugs, or the impact of sleep disturbance on neurological changes or cognitive impairment was not evaluated and should be considered in future research.

5. Conclusion

This study explored the influence of sleep on the relationship between CT and depression and found sleep to influence depression. Results highlight the use of sleep interventions as an avenue to both treat and prevent depression in sleep disturbed populations and underscore the importance of assessing sleep disturbances in clinical care.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD,... Giles WH (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood - A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256 (3), 174–186. 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, ... Riemann D (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 52(6), 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, & Handelsman L (1997). Validity of the childhood trauma questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 340–348. 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, & Elliott DM (2003). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(10), 1205–1222. 10.1016/j-chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brostrom A, Wahlin A, Alehagen U, Ulander M, & Johansson P (2018). Sex-specific associations between selforeported sleep duration, depression, anxiety, fatigue and daytime sleepiness in an older community-dwelling population. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(1), 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Rush AJ, & Reynolds CF 3rd (2017). Clinical management of insomnia disorder. JAMA, 318(20), 1973–1974. 10.1001/jama.2017.15683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CE, Edinger JD, Kuchibhatla M, Lachowski AM, Bogouslavsky O, Krystal AD, ... Shapiro CM (2017). Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep, 40(4), 10.1093/sleep/zsxO19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Rodriguez VJ, Jones DL, & Kumar M (2018). Short circuit: Disaggregation of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol levels in HIV-positive, methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 33(1), e2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Lin H, Zhou L, Yan H, & He N (2014). Adverse childhood experiences and interaction with methamphetamine use frequency in the risk of methamphetamine-associated psychosis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edalati H, & Krank MD (2016). Childhood maltreatment and development of substance use disorders: A review and a model of cognitive pathways. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 27(5), 454–467. 10.1177/1524838015584370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Frain JA (2017). Exploring disrupted sleep in a population of older adults living with HIV. Sleep, 40(Suppl. 1), 10.1093/sleepj/zsx050.1034A385-A385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding recommendations. health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Lee C, Friedman EL, & Springer KW (2011). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for sleep problems in adulthood: Evidence from a US national study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(2), 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Green KA, & Mourgues P (2005). Longitudinal investigation of methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men in New York City: Findings from project BUMPS. Journal of Urban Health, 82(1), i18–i25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes M (2009). Statistical digital signal processing and modeling. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kajeepeta S, Gelaye B, Jackson CL , & Williams MA (2015). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 16(3), 320–330. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal AD (2012). Psychiatric disorders and sleep. Neurologic Clinics, 30(4), 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.0181389-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, & Kalista T (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in. patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep, 31(4), 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelli L, Petrelli C, & Serretti A (2015). The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 665–680. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuive TG, & Miranda J (2008). New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: Policy implications. Health Affairs, 27(2), 393–403. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, & Lautenschlager GJ (2004). A comparison of item response theory and confirmatory factor analytic methodologies for establishing measurement equivalence/invariance. Organizational Research Methods, 7(4), 361–388. [Google Scholar]

- Meth woes outlined in Alamosa County (2007, 2007/02/08/). Brief article Pueblo Chieftain; (Pueblo, CO: ). Retrieved from http://access.library.miami.edu/login?url = http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p = ITOF&sw=w&u = miami_richter&v = 2.1&it = r &id = GALE%7CA159051890&asid = C5773df8b6e2e0246484e53dd6f95. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2016). Commonly abused drugs. Washington, D.C: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Paterniti S, Sterner I, Caldwell C, & Bisserbe JC (2017). Childhood neglect predicts the course of major depression in a tertiary care sample: A follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 113 10.1186/sl2888-017-1270-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rumble ΜE, White KH, & Benca RM (2015). Sleep disturbances in mood disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 38(4), 743–759. http://dx.doi.0rg/lO.lOl6/j.psc.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short NA, Allan NP, & Schmidt NB (2017). Sleep disturbance as a predictor of affective functioning and symptom severity among individuals with PTSD: An ecological momentary assessment study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 97, 146–153. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury JC (2009). Sleep as a mediator in the pathway from violence-induced traumatic stress to poorer health and functioning: A review of the literature and proposed conceptual model. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 7(4), 223–244. 10.1080/15402000903190207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, & First ΜB (1992). The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 49(8), 624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugland K, Landr∅ H (2015). Long-term effects of extreme trauma on sleep quality and the circadian rhythm of sleep and wakefulness: An actigraphy study of ut∅ya survivors. The University of Bergen. [Google Scholar]