Abstract

Individuals with a history of childhood trauma experience deficits in emotion regulation. However, few studies have investigated childhood trauma and both perceived (i.e., self-report) and behavioral measures of distress tolerance. The current study evaluated associations between childhood trauma (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing family violence) and measures of perceived (Distress Tolerance Scale) and behavioral distress tolerance (i.e., Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, breath-holding). Participants were 320 undergraduate students with a history of interpersonal trauma (e.g., sexual/physical assault). Structural equation modeling was used to evaluate associations between frequency of childhood trauma type and distress tolerance. Greater childhood physical abuse was associated with higher perceived distress tolerance. Greater levels of witnessing family violence were associated with lower behavioral distress tolerance on the breath-holding task. No significant effects were found for Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test performance. Associations between childhood trauma and emotion regulation likely are complex and warrant further study.

Keywords: Child abuse, emotion regulation, maltreatment, physical abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexual abuse, sexual assault

Introduction

Distress tolerance (DT), the perceived or actual ability to withstand negative internal states (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Zvolensky, 2005), has gained increasing attention in recent years, due to its association with a number of psychiatric disorders, and its potential to be targeted via clinical intervention. Low levels of DT have evidenced associations with greater levels of anxiety (Bernstein, Marshall, & Zvolensky, 2011; Kraemer, Luberto, & McLeish, 2013), disordered eating (Lavender, Happel, Anestis, Tull, & Gratz, 2015), substance use and related disorders (Buckner, Keough, & Schmidt, 2007; Daughters et al., 2005; Daughters, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Brown, 2005), and suicidal ideation (Anestis, Bagge, Tull, & Joiner, 2011; Anestis & Joiner, 2012). Other work has identified associations between high levels of DT and increased capability for suicide, although it is currently unclear at what levels or under what conditions high DT is maladaptive (Anestis, Bender, Selby, Ribeiro, & Joiner, 2011; Anestis, Knorr, Tull, Lavender, & Gratz, 2013). Studies conducted within trauma-exposed samples also have found that DT is inversely associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, both in community and treatment-seeking samples (Marshall-Berenz, Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, 2010; Vujanovic, Rathnayaka, Amador, & Schmitz, 2016; Vujanovic, Youngwirth, Johnson, & Zvolensky, 2009). Theoretical models posit that low DT plays a causal role in experiential avoidance (e.g., avoidant coping), a key mechanism in etiological and maintenance models of PTSD and related disorders (Vujanovic, Bernstein, & Litz, 2010; Vujanovic, Litz, & Farris, 2015).

One ongoing challenge to the investigation of DT is the lack of correspondence among self-report and behavioral measures purported to assess DT. The lack of clarity of such measures, combined with the manner in which they are referred to interchangeably in the literature, limits our ability to evaluate the patterns of association between DT measures and clinical problems of interest. DT measures tend to be characterized on two dimensions: assessment modality (i.e., self-report vs. behavioral assessment) and type of distress (i.e., physical vs. psychological/emotional). Self-report DT measures assess an individual’s perception of how well they can withstand negative emotional states (e.g., Simons & Gaher, 2005). Behavioral DT measures assess an individual’s latency to termination of an unpleasant stimulus (e.g., Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2003). The overarching pattern of findings regarding DT measurement indicates that self-report DT measures tend to be moderately correlated with one another, regardless of type of distress (Bernstein, Zvolensky, Vujanovic, & Moos, 2009; McHugh et al., 2011; McHugh & Otto, 2012); behavioral measures tend to be moderately correlated with one another, regardless of type of distress (Marshall-Berenz et al., 2010; McHugh et al., 2011); and self-report and behavioral measures are typically not significantly correlated (Anestis, Tull, Bagge, & Gratz, 2012; Marshall-Berenz et al., 2010; McHugh et al., 2011). From here on, we will refer to self-report measures of DT as “perceived DT,” and behavioral measures as “behavioral DT.” Given that measures of perceived and behavioral DT are not assessing a single DT construct, efforts are needed to better define the nature and correlates of these constructs.

Childhood trauma is a promising factor for understanding etiology of low perceived or behavioral DT. There is a substantial literature supporting associations between childhood trauma and risk for psychopathology (Kendler et al., 2000). Furthermore, childhood appears to be a sensitive period for experiencing the deleterious effects of stress, such that childhood trauma impacts stress reactivity and emotion regulation as observed in self-report (Banducci, Hoffman, Lejuez, & Koenen, 2014; Burns, Fischer, Jackson, & Harding, 2012; Choi & Oh, 2014), clinical laboratory (Hagan, Roubinov, Mistler, & Luecken, 2014; Powers, Etkin, Gyurak, Bradley, & Jovanovic, 2015; Trickett, Gordis, Peckins, & Susman, 2014), and imaging studies (Birn, Patriat, Phillips, Germain, & Herringa, 2014; Dean, Kohno, Hellemann, & London, 2014). Few studies of childhood trauma and DT have been conducted, and available research has almost exclusively relied on self-report measures of DT. Across these studies, greater childhood trauma severity was associated with lower perceived DT in college students (Arens, Gaher, Simons, & Dvorak, 2014), adults seeking evaluation for bariatric surgery (Koball et al., 2015), and adults in residential substance use disorder treatment (Banducci et al., 2014). To our knowledge, Gratz, Bornovalova, Delany-Brumsey, Nick, and Lejuez (2007) conducted the only study to date evaluating associations between childhood trauma and behavioral DT. Gratz et al. (2007) found that, in a sample of adults in inpatient substance use treatment, greater levels of childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse were associated with lower behavioral DT, defined as the average performance on two separate behavioral DT tasks: the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (Lejuez et al., 2003) and the Mirror-Tracing Persistence Task (Quinn, Brandon, & Copeland, 1996). This article provided important preliminary data; however, the authors conducted separate models for each abuse type, precluding an ability to determine whether specific types of abuse are more relevant for understanding DT after accounting for covariation among child trauma types. Furthermore, measures of perceived DT were not incorporated, limiting an ability to evaluate the importance of assessment modality in the established associations.

No studies to date have evaluated concurrent associations between multiple types of childhood trauma and both perceived and behavioral measures of DT. Peripheral literature supports preliminary associations between lifetime trauma load (i.e., not specific to childhood) and perceived (Vujanovic et al., 2016) and behavioral (i.e., breath-holding duration; Berenz, Vujanovic, Coffey, & Zvolensky, 2012) measures of DT; however, systematic, comprehensive studies are lacking. Enhancing our understanding of the potential role of childhood trauma in the etiology of perceived and behavioral DT may inform transdiagnostic theoretical and clinical models of DT and psychiatric risk.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate concurrent associations between childhood trauma and multiple measures of perceived and behavioral DT in a sample of young adults with a lifetime history of interpersonal trauma exposure (e.g., sexual/physical assault). The current investigation examined three types of childhood trauma (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing family violence) in relation to perceived (i.e., Distress Tolerance Scale [DTS]) and behavioral (i.e., Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test [PASAT], breath-holding [BH]) DT. Based on preliminary data from past studies (Banducci et al., 2014; Gratz et al., 2007; Koball et al., 2015), we hypothesized that greater levels of childhood trauma would be associated with lower levels of perceived and behavioral DT in adulthood, above and beyond theoretically relevant covariates (e.g., sex, PTSD symptom severity, non-child trauma load).

Method

Participants

Participants were a sub-set of 320 undergraduate students (75% women) participating in “Spit for Science,” a large genetically informed university-wide study of the progression and correlates of substance use and emotional health in college students at Virginia Commonwealth University (Dick et al., 2014). Individuals from the first three cohorts of the Spit for Science study were invited to determine eligibility for the current study of interpersonal trauma exposure and alcohol use.

Measures

The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000) is a self-report measure assessing whether and when participants experienced a range of potentially traumatic events (PTEs; e.g., natural disaster, assault, accidents, illness/injury) and how many times each PTE occurred (1 = “once,” 2 = “twice,” 3 = “3 times,” 4 = “4 times,” 5 = “5 times,” or 6 = “more than 5 times”). The TLEQ has evidenced good test-retest reliability and good convergent validity with interview assessments of PTE. Frequencies of childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, and witnessing family violence served as measures of childhood trauma load. Due to violations of assumptions of normality, the child trauma load variables underwent log transformation prior to entry in the regression models. Lifetime trauma history, defined as the number of trauma categories endorsed (excluding child trauma), was included as a covariate in the models.

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) is a 20-item self-report measure used to assess PTSD symptoms for individuals’ “most traumatic” life event. Each item corresponds to the symptom criteria for PTSD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Participants indicated the degree to which they have been bothered by a specific problem (e.g., “repeated, disturbing dreams of a stressful experience from the past”) in the past 30 days on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The PCL-5 evidences good reliability and validity in young adult college samples (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015). Preliminary studies indicate that cut-off scores ranging from 31–33 are optimal for identifying a positive PTSD screen (Bovin et al., 2015). The more conservative cut-off score of 33 was employed in the current study to determine screening status, and the PCL-5 total score was used as a continuous measure of past 30-day PTSD symptoms (α = .94).

Current alcohol consumption was assessed via items querying past 30-day alcohol use quantity (i.e., “On the days that you drank during the past 30 days, how many drinks did you usually have each day?”) and frequency (i.e., “During the past 30 days, how many days did you drink one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?”). Alcohol consumption was calculated by multiplying past 30-day quantity and frequency estimates. The measure was adapted from the timeline follow-back (Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

The DTS is a 15-item self-report measure of psychological or perceived DT, evaluating the extent to which respondents believe they can experience and withstand distressing emotional states (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree). Sample items include “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset” and “Being distressed or upset is always a major ordeal for me.” Higher scores on the DTS indicate greater DT. The DTS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Simons & Gaher, 2005). The DTS total score was used as an index of the extent of each respondent’s perceived ability to tolerate negative emotional states (α = .92), consistent with relevant past literature (Vujanovic et al., 2013).

The BH Task (Hajek, Belcher, & Stapleton, 1987) is a behavioral measure of physical DT. The task requires participants to hold their breath as long as possible. DT is defined as the length of time (average of two trials, in seconds) that participants are able to hold their breath (Daughters et al., 2005; Hajek et al., 1987), with greater time indicating greater DT. The BH task has been used in past work with trauma-exposed populations (Marshall-Berenz, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2011).

The PASAT (Lejuez et al., 2003) is a behavioral index of psychological DT. Participants are instructed to compute the sum of two digits presented in sequence. After answering the sum, the participant is then repeatedly presented with a new digit that must be added to the prior digit, ignoring the initial digit. The interval between which numbers are presented decreases over time, making correct responses increasingly difficult. The participant may terminate the task at any time during its final 5 minutes. DT is defined as latency (in seconds) to termination of the task (Lejuez et al., 2003), with greater latency indicating DT. The PASAT is a well-established measure of DT (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010).

Procedure

Details on the parent Spit for Science study have been published elsewhere (Dick et al., 2014). Current study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), hosted at Virginia Commonwealth University (Harris et al., 2009). The current study recruited participants from the first three cohorts of Spit for Science (enrolled between 2011–2013; N = 7,603; 61.1% women; 50.2% Caucasian, 19.5% Black, 16.3% Asian, 14% other) on the basis of endorsement of past 30-day alcohol use and lifetime trauma exposure at one or more Spit for Science assessments.

Of the 3,570 initially contacted, 21.1% (n = 755) made contact with the research team by completing a form indicating their interest in learning more about the study. Interested participants were sent a link to the online consent form, a brief screening item (i.e., “Have you had one or more alcoholic drinks (e.g., beer, wine, liquor) in the past 30 days?”), and the survey enrollment link. Further, 74% of interested individuals (n = 557) endorsed current alcohol use and consented to participate. After completing online informed consent procedures, they completed a battery of self-report and behavioral measures online via REDCap. Of the individuals who consented, 86.8% (n = 501) of the sample completed all measures. Based on responses on the TLEQ, 320 participants with complete study data endorsed one or more instances of directly experiencing or witnessing physical assault, sexual assault, or unwanted sexual experience and were included in the current study analyses. Thirteen participants had missing data for the behavioral DT tasks and were excluded from analyses. Participants were compensated $20 in cash for completing the study. The Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University approved all study procedures for both the parent study and the current study.

Data analytic plan

Data management and correlations were conducted in SPSS Statistics 22, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted in Mplus version 7 with bootstrapping to estimate confidence intervals (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Variables were examined for normality and outliers; behavioral indices of DT (i.e., latency to termination on the PASAT and Breath-Holding Task) were log transformed to accommodate the assumption of multivariate normality prior to inclusion in the SEM models. Zero-order correlations were examined among demographic and primary study variables. To address the primary study hypotheses, a structural equation model was used to model the association of DT measures (e.g., DTS-total score) with childhood trauma indices (i.e., frequency of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing family violence) while adjusting for: (a) previously identified covariates, namely sex, alcohol consumption (past 30-day quantity * frequency), lifetime trauma load (excluding childhood trauma), and PCL-total score, and (b) the inter-correlation of DT measures. Given that past studies have documented significant associations between behavioral measures of DT, the SEM approach is necessary to accurately estimate the association of childhood trauma with each specific DT measure.

Results

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations

Participants were 320 young adults (75.4% women; Mage = 18.5 years, SD = 0.7). Table 1 provides information regarding participant characteristics. The sample was racially diverse, with 40% of the sample identifying as non-white.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 58.6% |

| Black/African American | 18.8% |

| Asian | 8.3% |

| More than one race | 7.3% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.4% |

| Chose not to answer | 1.3% |

| Childhood traumatic event types | |

| Childhood sexual abuse by someone 5+ years older (<13 years old) | 12.7% |

| Childhood sexual abuse by someone close to your age (<13 years old) | 15.9% |

| Childhood sexual abuse (age 13–18) | 17.5% |

| Childhood physical abuse | 17.2% |

| Witnessing family violence | 34.7% |

| PCL-5 PTSD screen (cut-off: 33) | 27.6% positive |

| Past 30-day alcohol use frequency (days) | 6.9 (5.9) |

| Past 30-day alcohol use quantity (average # drinks) | 4.1 (2.5) |

Note: “PCL-5” = PTSD checklist for DSM-5.

Approximately one quarter of the sample screened positive for PTSD on the PCL-5. Participants endorsed using alcohol approximately 1–2 times per week and consuming an average of four drinks per occasion. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for primary study variables. Male sex was associated with greater past 30-day alcohol consumption. Female sex was associated with greater childhood sexual abuse and lower DT on the DTS and the BH task. Older age was associated with a greater number of lifetime traumatic events. Greater trauma load was associated with greater alcohol consumption, PTSD symptom severity, and childhood sexual abuse, as well as lower perceived DT on the DTS. Greater PTSD symptoms were associated with greater alcohol consumption, childhood sexual abuse, and childhood physical abuse, as well as lower DT on the DTS and the BH task. Childhood trauma counts were moderately correlated with one another, and the PASAT and BH task were positively correlated with one another. Childhood sexual abuse was associated with lower perceived DT on the DTS, childhood physical abuse was associated with lower DT on the PASAT, and witnessing family violence was associated with lower DT on the BH task.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (0 = male, 1 = female) | — | 74.7% female | |||||||||

| 2. Age (years) | −.19* | — | 18.54 (.70) | ||||||||

| 3. Alcohol consumption | −.25** | .04 | — | 31.30 (36.80) | |||||||

| 4. Lifetime trauma load | −.05 | .17** | .18** | — | 4.47 (2.13) | ||||||

| 5. PCL-Total Score | .11* | .01 | .18** | .32** | — | 22.51 (17.18) | |||||

| 6. Childhood sexual abuse count | .18** | .08 | −.04 | .19** | .12* | — | 1.23 (2.60) | ||||

| 7. Childhood physical abuse count | −.07 | −.06 | .02 | .00 | .14* | .12* | — | .68 (1.80) | |||

| 8. Witnessing family violence count | .09 | .02 | .07 | .10 | .09 | .18** | .44** | — | 1.51 (2.41) | ||

| 9. DTS-Total Score | −.16* | .01 | −.14* | −.18** | −.51** | −.13* | .05 | −.05 | — | 43.95 (12.44) | |

| 10. PASAT (seconds) | .03 | .05 | .04 | .06 | −.05 | −.08 | −.11* | −.05 | .07 | — | 139.33 (123.55) |

| 11. Breath-Holding (seconds) | −.24** | .03 | −.01 | .04 | −.14* | −.07 | −.04 | −.13* | .14* | .10 | 52.39 (30.31) |

Note: “Alcohol consumption” = past 30-day alcohol use quantity * frequency; “Lifetime trauma load” = number of trauma categories endorsed on Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ), excluding child trauma; “PCL-Total Score” = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 total score; “Childhood sexual abuse counts” = Number of incidents of unwanted sexual contact prior to age 18 endorsed on TLEQ (possible range: 0–12); “Childhood physical abuse count” = Number of incidents of childhood physical abuse endorsed on TLEQ (possible range: 0–6); “Witnessing family violence count” = Number of incidents of witnessing family violence endorsed on TLEQ (possible range: 0–6); “DTS-Total Score” = Distress Tolerance Scale total score; “PASAT” = Latency to termination of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task in seconds; “Breath-Holding” = Average breath-holding duration in seconds.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Structural equation model analyses

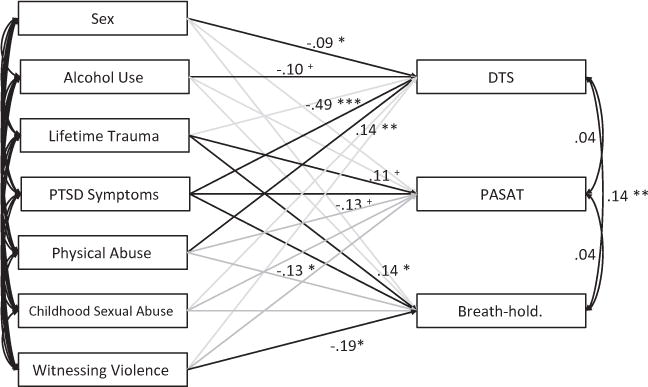

Each DT measure was regressed on indices of childhood trauma and covariates within a path model, which permitted adjusting each regression model for the inter-correlation of DT measures, while simultaneously estimating the inter-correlation of DT meaures, childhood trauma indices with covariates. The model fit the data well, χ2 (24) = 160.60, p < .0001, RMSEA < .0001, 95% CI RMSEA [0,0], CFI = 1.00. Theoretically-informative paths are summarized in Figure 1. The inter-correlation of behavioral DT and of childhood trauma indices with covariates were as described in Table 2 and are, therefore, ommitted from Figure 1, where doing so might ease intrepretation. Overall, the model accounted for a substantial proportion of variance in DTS-total score (R2 = .29) and breath-holding duration (R2 = .06), though less variance in PASAT duration (R2 = .04).

Figure 1.

Associations between child trauma and distress tolerance in an undergraduate sample. Note: Grey color indicates an included but nonsignificant path. “Alcohol Use” = past 30-day alcohol use quantity * frequency; “Lifetime Trauma” = number of trauma categories endorsed on Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ), excluding child trauma; “PTSD Symptoms” = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 total score; “Physical Abuse” = Number of incidents of childhood physical abuse endorsed on TLEQ; “Childhood Sexual Abuse” = Number of incidents of childhood sexual abuse endorsed on TLEQ; “Witnessing Violence” = Number of incidents of witnessing family violence endorsed on TLEQ; “DTS” = Distress tolerance scale, total score; “PASAT” = Latency to task termination on the Paced Auditory Serial Additional Test (in log seconds); “Breath-hold” = Latency to task termination on the Breath-Holding Task (in log seconds). +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Greater childhood physical abuse was significantly associated with higher levels of perceived DT (i.e., DTS total score), β = .14, p = .003, 95% CI [.05, .23], which was associated with male gender, β = −.09, p = .045, 95% CI [−.18, −.004], and showed a marginal inverse association with alcohol consumption, β = −.09, p = .062, 95% CI [−.17, −.01]. Greater frequency of witnessing family violence in childhood was significantly associated with decreased behavioral, physical DT (i.e., BH duration), β = −.19, p = .012, 95% CI [−.33, −.04], which was associated with non-childhood trauma load, β = .14, p = .020, 95% CI [.02, .25]. Behavioral, psychological DT (i.e., PASAT duration) showed a possible association with trauma load since childhood, β = .11, p = .079, 95% CI [−.02, .22], but no association with childhood trauma indices. Finally, PTSD symptom severity was associated with decreased distress tolerance across perceived DT, β = −.49, p < .001, 95% CI [−.58, −.39], behavioral, physical DT, β = −.13, p = .0345, 95% CI [−.25, −.01], and, marginally, behavioral, psychological DT, β = −.13, p = .062, 95% CI [−.25, .01].

Discussion

The current study investigated associations between childhood trauma (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing family violence) and both perceived (i.e., self-report) and behavioral measures of DT in a sample of undergraduates with a history of interpersonal trauma. Contrary to expectation, greater childhood physical abuse was significantly associated with higher perceived DT, after accounting for the effects of numerous covariates (e.g., PTSD symptoms, adult traumatic events, substance use) and other forms of childhood trauma, as well as inter-correlations among DT measures. It may be the case that young adults who have endured severe physical punishment perceive themselves as being more emotionally resilient than their peers. However, given that an emerging literature has linked high levels of perceived DT with greater acquired capability for suicide (Anestis et al., 2011, 2013), it is important for future research efforts to evaluate at what point and for whom high DT becomes maladaptive. Several studies have found evidence for associations between child maltreatment and risk for suicide (Briere, Madni, & Godbout, 2016; Hadland et al., 2012; Hoertel et al., 2015). It may be the case that high levels of perceived DT partially mediate an association between child maltreatment and risk for suicide. It is also noteworthy that physical abuse was not predictive of behaviorally observed DT. As such, these individuals may perceive their ability to tolerate distress as being greater than it is objectively. Future research that evaluates the potential importance of a “mismatch” between perceived and “actual” DT in relation to measures of emotion regulation, and emotional health more broadly, may be useful.

In line with hypotheses (i.e., greater levels of childhood trauma would be associated with lower DT), greater frequency of witnessing family violence during childhood was significantly associated with lower DT, as measured by the BH task. This finding is consistent with theoretical conceptualizations of the potential impact of trauma on DT (Vujanovic et al., 2016). Witnessing frequent family violence may condition individuals to associate physiological arousal (i.e., that experienced during a traumatic event) with negative affective states (e.g., fear, anger, etc.), which may cause physiological arousal, such as that experienced during BH, to feel more distressing. Further research is needed to verify the direction of effect, as well as to understand the processes by which witnessing violence in childhood may lead to deficits in emotion regulation capacity.

Childhood sexual abuse was not significantly associated with any DT measures after accounting for other forms of childhood trauma assessed in this study. This finding is consistent with related research in a clinically more severe sample of adult inpatients, whereby Banducci and colleagues (2014) did not identify unique associations between childhood sexual abuse and either DT or emotion dysregulation, after accounting for other forms of childhood maltreatment. These results highlight the importance of examining specific forms of childhood trauma in studies of emotion regulation and related processes.

The model did not fit the data well with respect to the PASAT in the context of other measures of DT. The PASAT may be better explained by other types of emotional processes and symptoms (e.g., depression) or more proximal measures, such as alcohol use (e.g., Gorka, Ali, & Daughters, 2012). Further evaluations to understand meaningful differences among behavioral measures of DT are needed, given that the tasks perform differently from one another in the context of such investigations.

Although not the central focus of this investigation, it is noteworthy that PTSD symptom severity was significantly negatively associated with all measures of DT, both perceived and behavioral, in the SEM model. This finding is in contrast with past literature, documenting distinct associations between PTSD symptomatology and self-report but not behavioral measures of DT (Farris, Vujanovic, Hogan, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2014; Marshall-Berenz et al., 2010). However, the effect size of the association between PTSD symptoms and self-report DT was greater than that for the behavioral DT measures in this sample. Identifying in which samples and under what conditions PTSD symptoms may relate to behavioral DT would inform our understanding of this discrepancy. Together, the findings from this investigation underscore the importance of assessing DT multimodally to better understand its complex relations with trauma and PTSD phenotypes.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our data precludes determination of the precise nature and direction of the relationships of interest. Similarly, the retrospective measures of childhood trauma may have been subject to recall bias. Prospective, longitudinal studies in children and adolescents are needed to determine the direction of the observed associations and to identify potential biological mechanisms linking child trauma to DT. Second, the study relied on self-report questionnaires of psychiatric symptoms. Inclusion of standardized clinical interview data in future studies would be useful to further evaluate the role of psychopathology in the observed associations across varied samples. Third, this investigation was limited in its ability to assess and control for potentially confounding environmental factors. Complementary methodologies designed to account for such factors (e.g., twin studies) would be useful for evaluating a causal influence of childhood trauma on DT. Fifth, although the study included multiple measures of DT, it is unclear how other behavioral measures, such as those assessing physical pain tolerance (e.g., Cold Pressor Task; Hines & Brown, 1932), may be associated with childhood trauma. Continued evaluation of the similarities and differences among DT measures, and the patterns of association with trauma phenotypes, will be useful for informing measure selection in future studies of child trauma and DT. In spite of these limitations, the current study informs clinically relevant theory regarding the potential impact of childhood trauma on adult affect regulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the VCU students for making this study a success, as well as the many VCU faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Dr. Berenz (1K99AA022385). Dr. Berenz is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (4R00AA022385). Dr. Amstadter is supported by a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and from NIH grants: K02AA023239, R01AA020179, P60MD002256, and MH081056-01S1. Spit for Science: The VCU Student Survey has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA107828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/WAMT.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bagge CL, Tull MT, Joiner TE. Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bender TW, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE. Sex and emotion in the acquired capability for suicide. Archives of Suicide Research. 2011;15:172–182. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.566058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Behaviorally-indexed distress tolerance and suicidality. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:703–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Knorr AC, Tull MT, Lavender JM, Gratz KL. The importance of high distress tolerance in the relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide potential. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2013;43:663–675. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Tull MT, Bagge CL, Gratz KL. The moderating role of distress tolerance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and suicidal behavior among trauma exposed substance users in residential treatment. Archives of Suicide Research. 2012;16:198–211. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.695269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arens AM, Gaher RM, Simons JS, Dvorak RD. Child maltreatment and deliberate self-harm: A negative binomial hurdle model for explanatory constructs. Child Maltreatment. 2014;19:168–177. doi: 10.1177/1077559514548315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Hoffman EM, Lejuez C, Koenen KC. The impact of childhood abuse on inpatient substance users: Specific links with risky sex, aggression, and emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:928–938. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Coffey SF, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity and breath-holding duration in relation to PTSD symptom severity among trauma exposed adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A, Marshall EC, Zvolensky MJ. Multi-method evaluation of distress tolerance measures and construct(s): Concurrent relations to mood and anxiety psychopathology and quality of life. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 2011;2:386–399. doi: 10.5127/jep.006610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Moos R. Integrating anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance: A hierarchical model of affect sensitivity and tolerance. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Patriat R, Phillips ML, Germain A, Herringa RJ. Childhood maltreatment and combat posttraumatic stress differentially predict fear-related fronto-subcortical connectivity. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:880–892. doi: 10.1002/da.22291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2015;28:1379–1391. doi: 10.1037/pas0000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Madni LA, Godbout N. Recent suicidality in the general population multivariate association with childhood maltreatment and adult victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016;31:2063–3079. doi: 10.1177/0886260515584339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EE, Fischer S, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2012;36:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Oh KJ. Cumulative childhood trauma and psychological maladjustment of sexually abused children in Korea: Mediating effects of emotion regulation. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez C, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Psychological distress tolerance and duration of most recent abstinence attempt among residential treatment-seeking substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:208–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AC, Kohno M, Hellemann G, London ED. Childhood maltreatment and amygdala connectivity in methamphetamine dependence: A pilot study. Brain and Behavior. 2014;4:867–876. doi: 10.1002/brb3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, Kendler K. Spit for science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics. 2014;5:47. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Vujanovic AA, Hogan J, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Main and interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and physical distress intolerance with regard to PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed smokers. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2014;15:254–270. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.834862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Ali B, Daughters SB. The role of distress tolerance in the relationship between depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:621–626. doi: 10.1037/a0026386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Bornovalova MA, Delany-Brumsey A, Nick B, Lejuez CW. A laboratory-based study of the relationship between childhood abuse and experiential avoidance among inner-city substance users: The role of emotional nonacceptance. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Marshall BD, Kerr T, Qi J, Montaner JS, Wood E. Suicide and history of childhood trauma among street youth. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:377–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MJ, Roubinov DS, Mistler AK, Luecken LJ. Mental health outcomes in emerging adults exposed to childhood maltreatment: The moderating role of stress reactivity. Child Maltreatment. 2014;19:156–167. doi: 10.1177/1077559514539753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Belcher M, Stapleton J. Breath-holding endurance as a predictor of success in smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EA, Brown G. A standard stimulus for measuring vasomotor reactions: Its application in the study of hypertension. Paper presented at the Mayo Clinic Proceedings 1932 [Google Scholar]

- Hoertel N, Franco S, Wall MM, Oquendo MA, Wang S, Limosin F, Blanco C. Childhood maltreatment and risk of suicide attempt: A nationally representative study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;76:916–923. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koball AM, Himes SM, Sim L, Clark MM, Collazo-Clavell ML, Mundi M, Grothe KB. Distress tolerance and psychological comorbidity in patients seeking bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2015;26:1559–1564. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1926-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KM, Luberto CM, McLeish AC. The moderating role of distress tolerance in the association between anxiety sensitivity physical concerns and panic and PTSD-related re-experiencing symptoms. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2013;26:330–342. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2012.693604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The traumatic life events questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Happel K, Anestis MD, Tull MT, Gratz KL. The interactive role of distress tolerance and eating expectancies in bulimic symptoms among substance abusers. Eating Behaviors. 2015;16:88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Brown RA. A modified computer version of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) as a laboratory-based stressor. The Behavior Therapist. 2003;26:290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Multimethod study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jts.20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ. Main and interactive effects of a nonclinical panic attack history and distress tolerance in relation to PTSD symptom severity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Murray HW, Hearon BA, Gorka SM, Otto MW. Shared variance among self-report and behavioral measures of distress intolerance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35:266–275. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Otto MW. Refining the measurement of distress intolerance. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(3):641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus user’s guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 8th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Powers A, Etkin A, Gyurak A, Bradley B, Jovanovic T. Associations between childhood abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and implicit emotion regulation deficits: Evidence from a low-income, inner-city population. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2015;78:251–264. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1069656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EP, Brandon TH, Copeland AL. Is task persistence related to smoking and substance abuse? The application of learned industriousness theory to addictive behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:186–190. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.4.2.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The distress tolerance scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Gordis E, Peckins MK, Susman EJ. Stress reactivity in maltreated and comparison male and female young adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1077559513520466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic A, Bernstein A, Litz B. Traumatic stress. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Hart AS, Potter CM, Berenz EC, Niles B, Bernstein A. Main and interactive effects of distress tolerance and negative affect intensity in relation to PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Litz BT, Farris SG. Distress tolerance as risk and maintenance factor for PTSD: Empirical and clinical implications. In: Martin CR, Preedy VR, Patel VB, editors. Comprehensive guide to post-traumatic stress disorder. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Rathnayaka N, Amador CD, Schmitz JM. Distress tolerance: Associations with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among trauma-exposed, cocaine-dependent adults. Behavior Modification. 2016;40:120–143. doi: 10.1177/0145445515621490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Youngwirth NE, Johnson KA, Zvolensky MJ. Mindfulness-based acceptance and posttraumatic stress symptoms among trauma-exposed adults without axis I psychopathology. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Keane T, Palmieri P, Marx B, Schnurr P. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) 2013 Retrieved from www.ptsd.va.gov.