Abstract

Perceiving is the process by which evanescent sensations are linked to environmental cause and made enduring and coherent through the assignment of meaning, utility, and value. Fundamental to this process is the establishment of associations over space and time between sensory events and other sources of information. These associations provide the context needed to resolve the inherent ambiguity of sensations. Recent studies have explored the neuronal bases of contextual influences on perception. These studies have revealed systems in the brain through which context converts neuronal codes for sensory events into neuronal representations that underlie perceptual experience. This work sheds light on the cellular processes by which associations are learned and how memory retrieval impacts the processing of sensory information. Collectively, these findings suggest that perception is the consequence of a critical neuronal computation in which contextual information is used to transform incoming signals from a sensory-based to a scene-based representation.

Perceiving is a common English word with a number of related colloquial meanings: it is the act of understanding, realizing, seeing, noticing, or becoming aware of. In modern neuroscience, our working definition of perception is captured well by the Oxford English Dictionary: “The action of the mind by which it refers its sensations to an external object as their cause.” This definition has roots in the corpus of eighteenth-century philosophy–beginning with George Berkeley and David Hume–was expanded upon by later British associationists, and became a foundation of both experimental psychology and modern neuroscience.

There are two essential features of this definition, the first being the distinction between perception and sensation. Sensation is the immediate neurobiological consequence of stimulating sensory transducers1 such as photoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, and chemoreceptors. Sensory events are ubiquitous and can affect behavior directly–the spinal reflex of pulling your hand back from a hot surface is one simple example–but they are fleeting, discontinuous, and lacking semantic content. Perception enriches sensation by reference to other knowledge or experience. In the words of British associationist John Stuart Mill, “perception reflects the permanent possibilities of sensation”2–things as they were or might be–and in doing so reclaims from evanescent sensory events the enduring structural and relational properties of the world. The philosopher and psychologist William James expressed a similar view in his discussion of “The Perception of Things”: “Perception thus differs from sensation by the consciousness of farther facts associated with the object of the sensation.”3 Or in the prescient words of nineteenth-century perceptual psychologist James Sully: the mind “supplements a sense impression by an accompaniment or escort of revived sensations, the whole aggregate of actual and revived sensations being solidified or ‘integrated’ into the form of a percept.”4 Building on the philosophical traditions from which the discipline of psychology was born, William James further stressed the need for associative neuronal processes to achieve this integration: “The chief cerebral conditions of perception are the paths of association irradiating from the sense-impression.”5

The second essential feature of neuroscientists’ definition of perception concerns the attributes of the thing (or things) to which sensation is referred. In particular, the referent is viewed as the “cause” of sensation. This concept was developed by the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid, who argued that sensation “suggests to us” an object as its source: “We all know that a certain kind of sound suggests immediately to the mind a coach passing in the street.”6 As James later noted, perception is “the consciousness of particular material things present to sense.”7 This attribution to the source of sensation is profoundly important and meaningful for perception and behavior. To fully appreciate this importance, it is useful to consider the larger function of sensory systems and the computational problems faced by them. For a variety of reasons–some technical, some conceptual, and some historical–this consideration is easiest to undertake for the visual modality, and that is the approach I will use herein. The principles of perceiving and the underlying neuronal mechanisms revealed by the study of vision nonetheless have broad relevance to other sensory modalities.

Figure 1 illustrates what I call the “central problem of vision.” Technically this is two problems, one of which is optical and the other biological. The optical problem involves reflection of light off of environmental surfaces, refraction of that light by the crystalline lens of the eye, and, finally, projection of the light onto the back surface of the eye–the surface known as the retina,8 which is lined with neuronal tissue responsible for phototransduction–to form the retinal image. This image is merely a pattern of light that changes in intensity and wavelength over space and time. But our survival depends on our ability to engage with–to recognize and to navigate amongst–the features of the visual scene that gave rise to the retinal image. The biological problem, which is by far the more difficult of the two, thus involves reconstruction of the properties of the visual scene, given only the pattern of light present in the retinal image. This inverse problem of optics is an example of what is known formally as an ill-posed problem: it is a problem without a unique solution. Because of the dimensionality reduction that accompanies optical projection of the world onto the retina, there is simply not sufficient information present in the retinal image to uniquely identify its environmental causes. To put it bluntly, the number of visual scenes that could give rise to any specific retinal image is infinite.

Figure 1. The Central Problem of Vision.

The problem is twofold: one component is optical and the other biological. The optical problem involves reflection of light off of surfaces in the visual environment. This light is refracted by the crystalline lens at the front of the eye, resulting in a pattern of light (the retinal image) that is projected and focused on the retinal surface at the back of the eye. The biological problem–the problem of perception–involves identification of the elements of the visual scene that gave rise to the retinal image. This is a classic inverse problem for which there is no unique solution: a given retinal image could be caused by any one of an infinite set of visual scenes.

This fundamental ambiguity is not reflected in human perceptual experience, however, for we generally arrive quickly at a solution and the chosen solution is nearly always correct (in that it reflects the “true” environment). This is only possible by using other sources of information, including the spatial relationships between different features of the image (spatial context), the observer’s prior experiences (temporal context), and consistent properties of the visual world (for example, that light comes from above) that have become embedded in the computational machinery of the brain through natural selection (evolutionary context). Recent experiments summarized herein have revealed much about how these contextual influences enable perception. Source: Figure prepared by author.

In view of this intrinsic ambiguity, perhaps the most astonishing thing about visual perceptual experience is that we rarely have difficulty arriving at a unique solution for the environmental cause of the retinal image. Moreover, the solution we adopt is nearly always the correct one (at least within margins of error allowable for our behavioral interactions with the world). Those cases where we arrive at the wrong solution are what we call “illusions.” Vision is able to accomplish reliable disambiguation of the retinal image by virtue of context, which, broadly speaking, consists of other pieces of information that are either 1) co-present in the retinal image (spatial context); 2) learned based on the observer’s prior experience with the world (temporal context); or 3) embedded in the computational machinery of the brain as a result of evolution in an environment that has consistent and well-defined properties (evolutionary context). Con text is thus James’s “farther facts associated with the object of sensation.” Using the available context as clues, the process of disambiguation–the process of perceiving–is best characterized as probabilistic inference about the cause of sensation. Again according to James, “perception is of probable things.”9 Or to use a familiar colloquialism, “we generally see what we expect to see.”

Context plays an extended role in perception in that it also helps resolve symbolic form. Sensory inputs are replete with symbolism–often quite abstract and multifaceted–and to perceive is to grasp the meanings of the symbols. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is human language, which is by definition an experience-dependent mapping of auditory and visual stimuli onto meaningful objects, actions, and concepts. To illustrate how con text resolves this mapping and, by doing so, makes perception possible, William James offered the phrase Pas de lieu Rhone que nous.10 If the listener assumes that the spoken phrase is French, it is unintelligible. If, however, the listener is informed that the spoken phrase is English, the very same sounds are perceived as paddle your own canoe. James further noted that “as we seize the English meaning the sound itself appears to change.” In other words, the percept is both reconciled and subjectively qualified by the context provided.

With these phenomenological aspects of perception in mind, research in recent years has focused on the mechanisms by which contextual cues modulate neuronal signals originating from the senses, thereby reflecting the thing perceived. In the case of vision, the question is: how do neuronal signals that initially reflect the properties of the retinal image become transformed (via context) such that they reflect instead the properties of the visual scene? Based on the discoveries presented below, I will argue that this transformation from an image-based representation to a scene-based representation is among the most basic and fundamental operations of the cerebral cortex11 and is the neurobiological explanation for the fact that “perception reflects the permanent possibilities of sensation.”

To provide a foundation for understanding the neuronal bases of perceiving, I will briefly review our present understanding of the organization of the primate visual system. Much of this information has come from the use of three key experimental approaches:

Neuroanatomy: These studies, which are made possible by methods for selective visual labeling of brain tissue, provide a picture of neurons12–the basic cellular elements of the brain–as well as a picture of the wiring diagram of neuronal connectivity.

Neurophysiology: These studies reveal the types of sensory signals carried by neurons and the manner in which those signals are transformed at each computational stage in the signal processing hierarchy. In practice, this information is recorded physiologically by evaluating neuronal receptive field13 properties. The receptive field (rf) is a central concept in sensory neurobiology and is defined as the region of sensory space that, when stimulated, elicits a change in the activity of the recorded neuron (typically quantified as frequency of action potentials14). Visual rf properties may include, in addition to spatial location, sensitivity to complex spatial, temporal, and/or chromatic properties of light. A more recent concept important for this discussion of perception is that of the rf surround (sometimes known as the “non-classical rf”). A sensory stimulus that falls in a neuron’s rf surround does not directly cause a change in activity (by definition), but rather has the ability to modulate activity driven by a stimulus in the rf. As we shall see, the rf surround provides a mechanism by which contextual cues may influence (and disambiguate) neuronal responses to sensory stimuli.

Behavioral analysis: This approach involves acquiring behavioral reports of subjective states, such as those associated with perceiving. These behavioral measures reveal correlations (and implied causal relationships) between a perceptual state and the neuronal signals recorded from specific anatomical circuit locations.

The first act of visual processing, which occurs in the retina, is phototransduction (the conversion of energy in the form of light into energy in the form of neuronal activity). Signals leaving the retina are carried by the optic nerve/tract15 and convey information about the location of a stimulus in visual space, the wavelength composition of the stimulus, and about spatial and temporal contrast between different stimuli. Optic tract fibers synapse16 in a region of the thalamus (a form of sensory transponder located in the center of the forebrain17), known as the lateral geniculate nucleus,18 and the signals are passed on from there via a large fiber bundle to terminate in the primary visual cortex,19 or area V1 (Figure 2). Area v1 is located in the occipital lobe (the most posterior region) of the cerebral cortex, which is the massive convoluted sheet of neuronal tissue that forms the exterior of the forebrain. Signals recorded physiologically reveal that v1 neurons extract a number of basic features of the pattern of light in the retinal image, including position in visual space, color, contour orientation, motion direction, and distance from the observer. These signals ascend further to contribute to functionally specific processing–object recognition, spatial understanding, visual-motor control–in a number of additional visual areas, which collectively make up approximately one-third of the human cerebral cortex.

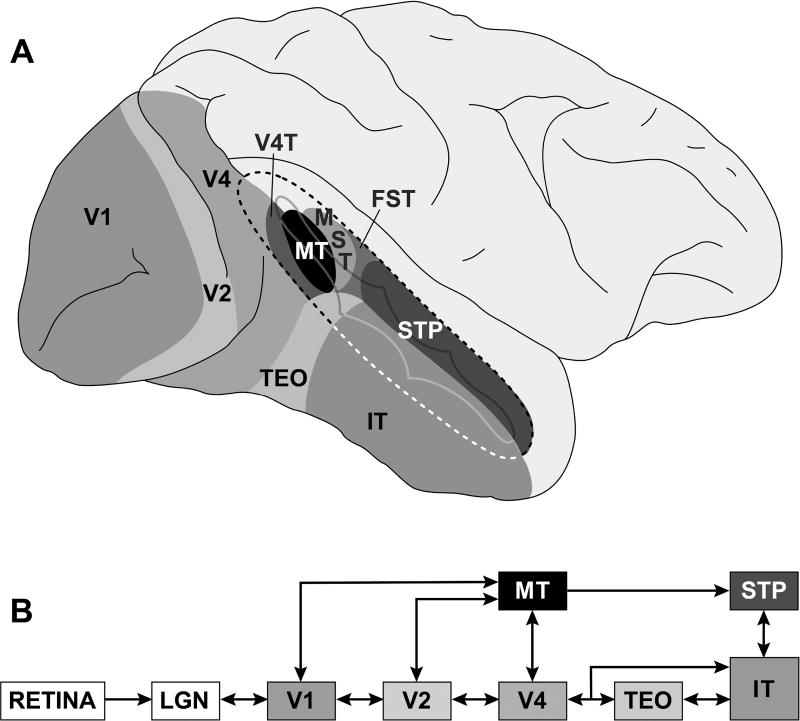

Figure 2. Locations and Connectivity of Cerebral Cortical Areas of Rhesus Monkey (Macaca mulatta) Involved in Visual Perception.

Because of the similarity of its visual functions to those of humans, the vast knowledge of the organization of its cerebral cortex, and the richness of its behavioral repertoire, the rhesus monkey has been an extremely powerful model for understanding the brain bases of visual perception.

(A) Lateral view of cerebral cortex of rhesus monkey. Front of brain is at right and top of brain is at top of image. Superior temporal sulcus is partially unfolded (dashed line) to show visual cortical areas that lie within. Differently shaded regions identify a subset (visual areas v1, v2, v4, v4t, mt, mst, fst, stp, teo, it) of the nearly three dozen distinct cortical areas involved in the processing of visual information.

(B) Connectivity diagram illustrating a subset of known anatomical projections from retina to primary visual cortex (v1) and up through the inferior temporal (it) cortex. Most projections are bi-directional.

Source: Figure prepared by author.

Attempts to understand how visual cortical neurons account for perceptual experience have been largely reductionist in approach. These experiments, which spearheaded the field of sensory neurobiology fifty years ago, typically involve manipulation of a very simple stimulus along a single sensory dimension–a contour is varied in orientation, a patch of light is varied in color, a moving texture is varied in directionality–and placed within the rf of a physiologically recorded neuron. This approach has revealed fundamental features of the ways in which basic attributes of a sensory stimulus are detected and encoded by neuronal activity. But in the end this approach has told us little about perception because the stimuli are devoid of meaning. They lack the context needed to identify environmental cause and are thus ambiguous in the most complete sense possible.

The alternative experimental approach is one in which the context is varied, such that the percept (the inferred environmental cause) is independent of the parameters of the sensory stimulus. The real world presents a rich set of such conditions, of course, but there is an advantage to an intermediate experimental approach in which perceptual and neuronal responses20 to a simple well-defined stimulus–the “target”–are evaluated in the presence of simple contextual manipulations.21 In our laboratory we have used both spatial and temporal context for this purpose. Spatial context is defined here as other (non-target) features of the retinal image, such as the color, pattern, or motion of spatial regions surrounding the target (the “surround”). There are many well-known perceptual phenomena in which experience of a simple target stimulus is markedly influenced by the surround. Perception of brightness and color hue, for example, are heavily context dependent (Figure 3), often in complex and revealing ways. We have also discovered and explored a number of compelling effects of context on perceived motion.22

Figure 3. Complex Influences of Spatial Context on Brightness Perception.

(A) Simultaneous contrast enhancement. The intensities of the two central squares are identical, but the central square on the left appears darker. This brightness illusion, which has been known for centuries, can be accounted for by the differences in spatial context (light on left and dark on right).

(B) The “corrugated plaid” illusion devised by vision scientist Edward Adelson shows the pronounced dependence of brightness perception on image cues for depth, form, and shading. Patches b1 and b2 are identical in intensity, but b2 appears brighter.

(C) By changing cues for depth, form, and shading, yet leaving the local luminance configuration intact, the brightness illusion present in (B) is greatly reduced. Patches c1 and c2 are identical in intensity and they appear approximately so.

The illusion can be accounted for by the use of contextual cues to identify the visual scene that produced the image. One important visual scene property is the reflectance of surfaces, since that property enables object recognition. The brightness values perceived in this illusion correspond to probabilistic inferences about surface reflectance that are driven by contextual cues that suggest a specific visual scene interpretation.

Source: Edward H. Adelson, “Perceptual Organization and the Judgment of Brightness,” Science 262 (1993): 2042–2044; and Thomas D. Albright, “Why Do Things Look as They Do?” Trends in Neuroscience 17 (1994): 175–177.

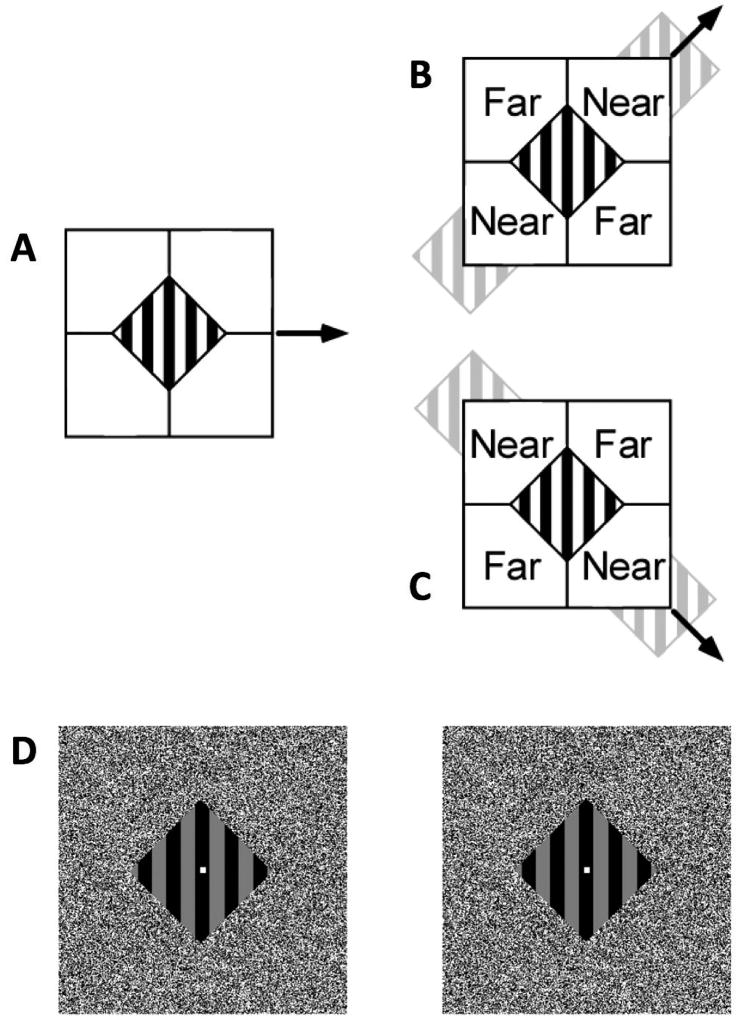

In all of these cases, the percept varies because the spatial context leads to different plausible interpretations of the cause of the sensory stimulus. My work with Gene Stoner (Salk Institute) on context-dependent visual motion perception illustrates this well.23 Stoner designed a stimulus in which a diamond-shaped pattern of vertical stripes was viewed in the context of a textured surround (Figure 4). (We call this the “barber diamond” stimulus because it mimics features of the classic “barber pole” illusion, in which rotating stripes appear to move downward along the axis of the pole.) Portions of the textured surround were manipulated (using binocular disparity cues24) such that they were perceived in different planes of depth. We used two complementary depth configurations: 1) foreground (Near) panels appear at the upper-right and lower-left corners of the stimulus and a background trough runs from the upper-left to lower-right (Figure 4B); and 2) foreground panels appear at the lower-right and upper-left and the background trough runs from lower-left to upper-right (Figure 4C). In both depth configurations, the diamond-shaped pattern of stripes appeared at an intermediate depth plane (above trough and below foreground panels). For each of these two configurations we moved the pat tern of stripes either leftward or rightward within the stationary diamond-shaped window.

Figure 4. Schematic Depiction of “Barber Diamond” Stimuli Used to Study the Influence of Context on Perceived Motion and Its Neuronal Correlates.

(A) Stimuli consisted of a moving pattern of vertical stripes framed by a static, diamond-shaped aperture. The striped pattern itself was placed in the plane of ocular fixation while four textured panels that defined the aperture were independently positioned in depth using binocular disparity cues. The striped pattern was moved either leftward or right ward on each trial. Each of the four stimulus conditions used was a unique conjunction of direction of motion (right versus left motion of the striped pattern) and depth-ordering configuration. The two conditions illustrated (B and C) were created using a rightward moving pattern of stripes; two additional conditions (not shown) were created using leftward moving stripes. Near and Far identify the depth-ordering of the textured panels relative to the depth plane of the striped pattern.

(B) Upper-right and lower-left panels were placed in the Near depth plane, while the upper-left and lower-right panels were in the Far depth plane. Line terminators formed at the boundary of Near surfaces and the striped pattern are classified as extrinsic features resulting from occlusion, and the striped pattern is perceived to extend behind the Near surface. (Note that the gray stripes in this illustration are not part of the stimulus and are used solely to illustrate perceptual completion.) Conversely, line terminators formed at the boundary of the Far surfaces and the striped pattern are classified as intrinsic: they appear to result from the physical termination of the surface upon which the stripes are “painted.” As a result of this depth-ordering manipulation and ensuing feature interpretation, observers typically perceive the moving pattern of stripes in (B) as belonging to a surface that slides behind the Near panels and across the Far panels (to the upper-right). This direction is identified with motions of intrinsic terminators.

(C) The condition shown contains the same rightward motion of the pattern of stripes, but employs the depth-ordering configuration that is complementary to (B). In this case, observers typically perceive the striped pattern as belonging to a surface that is drifting to the lower right.

(D) 3-D illustration of one depth-ordering configuration used for these experiments. The 3-D percept requires “free cross-fusing” of the left and right panels (such that the right eye is aimed at the left panel and the left aimed at the right). Those viewers capable of free fusing should perceive the 3-D layout of the stimulus. In practice, the central striped pattern also drifted leftward or rightward.

A demonstration of this depiction, with motion, is available at http://vcl-s.salk.edu/Research/Motion-Integration/.

Source: Robert O. Duncan, Thomas D. Albright, and Gene R. Stoner, “Occlusion and the Interpretation of Visual

Motion: Perceptual and Neuronal Effects of Context,” The Journal of Neuroscience 20 (2000): 5885–5897.

We predicted that the perceived direction of the stripes would vary depending on their depth relationships with the surround. To understand this prediction, note that the edges of the striped pattern that lie adjacent to a Far panel are readily (probabilistically) perceived as edges of an object in the visual scene. We call these “intrinsic” edges because they are intrinsic to the object that caused their presence in the retinal image. By contrast, edges of the striped pattern that lie adjacent to a Near panel are readily perceived as accidents of occlusion of one object by another. We call these “extrinsic” edges because they are extrinsic to all objects in the visual scene. Thus, the moving lines that rake (as retinal stimuli) along an intrinsic edge should be perceived as the consequence of a striped object moving through space in that direction. Conversely, the moving lines that rake along an extrinsic edge should be perceived as bearing no reliable relationship to the motion of the striped object, for it is impossible to verify, based upon these retinal motions, the extent to which the object moves under or parallel to the foreground surface. As a consequence of these depth-dependent perceptual interpretations of the cause of the retinal stimulus, the physically invariant motions should be perceived as arising from an object in the visual scene that slides along one or the other diagonal, depending on the spatial context. This is precisely what we found to be true; indeed, the effect is universal and striking.25

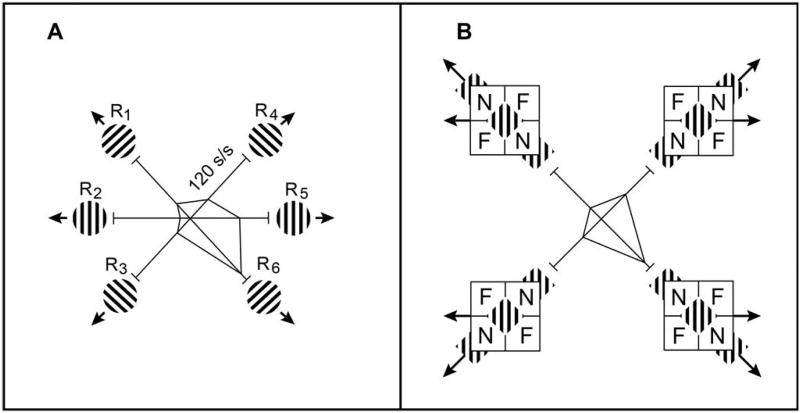

The configuration of these context-dependent motion stimuli enabled us to place them within the rfs of cortical neurons that respond selectively to the direction of stimulus motion. Such neurons are abundant in a small mid-level cortical region known as the middle temporal visual area, or area MT26 (Figure 2). A typical mt neuron responds best to movement of a pattern in a specific direction–upward, for example–within the rf, and response wanes as direction deviates from this “preferred direction.” Much evidence suggests that the activity of these neurons underlies the perception of motion,27 so we reasoned that the response of an mt neuron to the barber-diamond stimulus should vary depending on the direction perceived (as dictated by spatial context), even though the motion in the retinal image never changes. Figure 5 illustrates data from an mt neuron that does this. Critically, only the moving stripes were placed within the rf of the neuron; the spatial context was visible to the rf surround. The response of this neuron, like many others in area mt (about 25 percent of the total population), is modulated by the spatial context such that it represents the perceptually inferred motion of an object in the visual scene, rather than the “sensory” motions in the retinal image. We naturally presume that the activity underlies the perceptual experience.

Figure 5. Influence of Spatial Context on the Encoding of Visual Motion by Cortical Neurons.

Data were obtained by stimulating the rfs of neurons in area mt (see Figure 2) with unambiguously moving patterns of stripes (panel A) and with barber-diamond stimuli (panel B; see text and Figure 4 for stimulus description), for which the perceived direction is dictated by context.

(A) The striped pattern was moved in each of six different directions (indicated by small stimulus icons) within the rf of the recorded mt neuron. The motion percepts elicited by these six stimuli are determined solely by the physical motions of the stimulus. The mean neuronal responses are plotted in polar form, where the radius represents the frequency of action potentials (spikes per second) and the polar axis represents the direction that the stimulus moved. Like many mt neurons, this cell was highly selective, with a preference for motion down and to the right.

(B) The same mt neuron shown in (A) was in this case stimulated with four barber-diamond conditions. As detailed in text and in Figure 4, there are only two retinal image motion directions (left and right) present in these four stimuli, which are indicated by the black arrows on each stimulus icon. Because of the different depth configurations in the surround (see Figure 4), these two image motions are perceived to move in each of four unique directions (along the four diagonals), indicated by the gray arrows on each stimulus icon. We predicted that the neuronal response would be largest when the perceived motion matched the neuron’s known direction preference (established from the test shown in panel A), such as down and to the right. This is precisely what was observed. Importantly, the retinal image motions for the two conditions on the right side of the panel are physically identical, but the neuronal response reflects the direction perceived, which is the visual scene motion inferred based upon spatial context.

Source: Robert O. Duncan, Thomas D. Albright, and Gene R. Stoner, “Occlusion and the Interpretation of Visual

Motion: Perceptual and Neuronal Effects of Context,” The Journal of Neuroscience 20 (2000): 5885–5897.

The barber-diamond provides a dramatic demonstration of how an invariant retinal stimulus can be perceived differently depending on context. Another property of perception is that it often generalizes across different sensory attributes28: widely varying retinal stimuli will be perceived as arising from a common source in the visual scene. These effects are termed perceptual constancies.29 Size constancy, for example, refers to the fact that an object viewed from different distances will vary markedly in retinal image size but will be perceived as having the same size in the visual scene. This is a case in which the probable cause of the retinal stimulus is inferred using contextual cues for distance, such as linear perspective or binocular disparity.

In the laboratory we have studied a type of perceptual constancy known as “form-cue invariance,” which occurs when essential attributes of the visual scene, such as object form or motion, are extracted invariantly from the retinal image by generalizing across image attributes that distinguish object from background.30 The profile of Abraham Lincoln’s head, for example, is readily perceived regardless of whether it is defined relative to background by black-on-white, white-on-black, or red-on-green. This form of constancy reflects contextual information (evolutionary context) that is “built-in” the human visual system: to wit, we have evolved to operate in an environment in which the properties of light change over space and time, and objects are thus to varying degrees visible to us by different image cues, including brightness, color, and texture. Reliable perception depends on the ability to generalize across these state changes and extract the meaningful properties of the world.

We studied the neuronal basis of form-cue invariance using simple elongated rectangles that were defined by differences in brightness, texture, or flicker.31 When these different stimuli are moved, the percept of motion is invariant, despite the fact that the sensory attributes of the image vary markedly. When we presented motion sensitive mt neurons with these form-cue invariant motion stimuli, we discovered that the neuronal responses also generalized across the different form cues. We concluded that these responses underlie the invariant perceptual experience by representing common motions of objects in the visual scene, to the exclusion of information about the sensory features that distinguish the objects from the background.

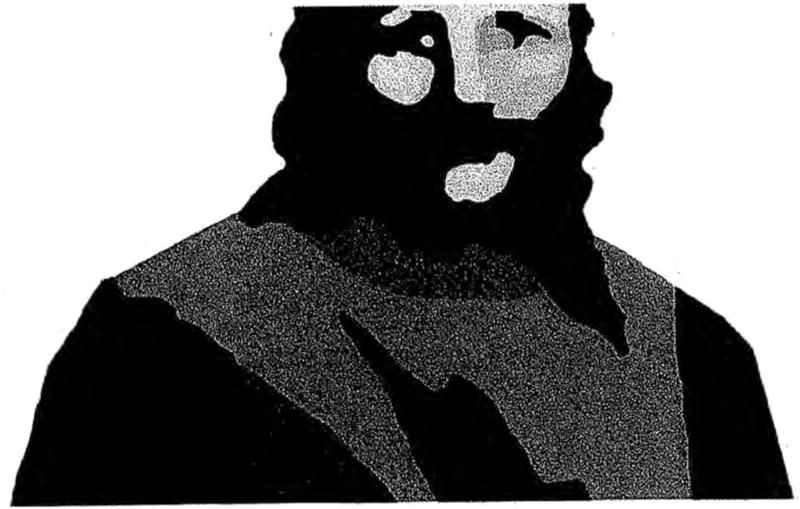

In the examples considered thus far, perception does not require reference to the observer’s prior personal experience with the world. Much of the time, however, the way we perceive a sensory stimulus depends heavily on what we have seen before. This temporal context is manifested perceptually both as the ability to identify the cause of a sensory stimulus and by the ability to identify its meaning (as symbolic form). A simple but dramatic demonstration of such effects can be seen in Figure 6. Without prior experience with this particular pattern of retinal stimulation, it is difficult to identify a probable environmental cause (other than a surface with an apparently random pattern of light and dark regions) or to grasp what the sensory features symbolize. Figure 8 (page 35) provides information that will help disambiguate the image in Figure 6, leading to a coherent and meaningful percept. Similarly, the visual perceptual experience of Devanagari (Hindi script) is markedly different before and after learning the written language. These temporal context effects are, in fact, ubiquitous and fundamental to perceiving. They are rooted in the phenomena of associative learning32 and memory retrieval33: as an observer learns the relationship between a sensory stimulus and the “farther facts associated with the object of sensation,” the stimulus alone is capable of eliciting retrieval of those “farther facts,” which become incorporated into the percept.

Figure 6. Demonstration of the Influence of Temporal Context on the Interpretation of a Sensory (Retinal) Stimulus.

To most observers, this figure initially appears as a random pattern with no clear perceptual interpretation. The perceptual experience elicited by this stimulus is radically (and perhaps permanently) different after viewing the pattern shown in Figure 8. Source: Paul B. Porter, “Another Puzzle-Picture,” The American Journal of Psychology 67 (3) (1954): 550–551.

Figure 8. Demonstration of the Influence of Temporal Context on the Interpretation of a Sensory (Retinal) Stimulus.

Most observers will experience a clear meaningful percept upon viewing this pattern. After achieving this percept, refer back to Figure 6. The experience of that image should now be markedly different, with a perceptual interpretation that is now driven largely by information drawn from memory. Figure previously published in Thomas D. Albright, “On the Perception of Probable Things: Neural Substrates of Associative Memory, Imagery and Perception,” Neuron 74 (2) (2012): 227–245.

To understand the neuronal events that underlie the perceptual effects of temporal context, we have explored both the learning of sensory associations and the mechanisms by which associative recall influences perception. Sensory associative learning is the most common form of learning: it inevitably results when stimuli appear together in time, and particularly so in the presence of reinforcement; it can occur without awareness (“classical conditioning”) or with (“instrumental conditioning”). The product of associative learning is that presentation of one stimulus elicits retrieval of its associate and all of the experience that that retrieval entails. For Pavlov’s dog, for example, the learned association between the sound of the bell and the taste of food elicited in the dog the physiological manifestations of eating (such as salivating) when the bell alone was struck.

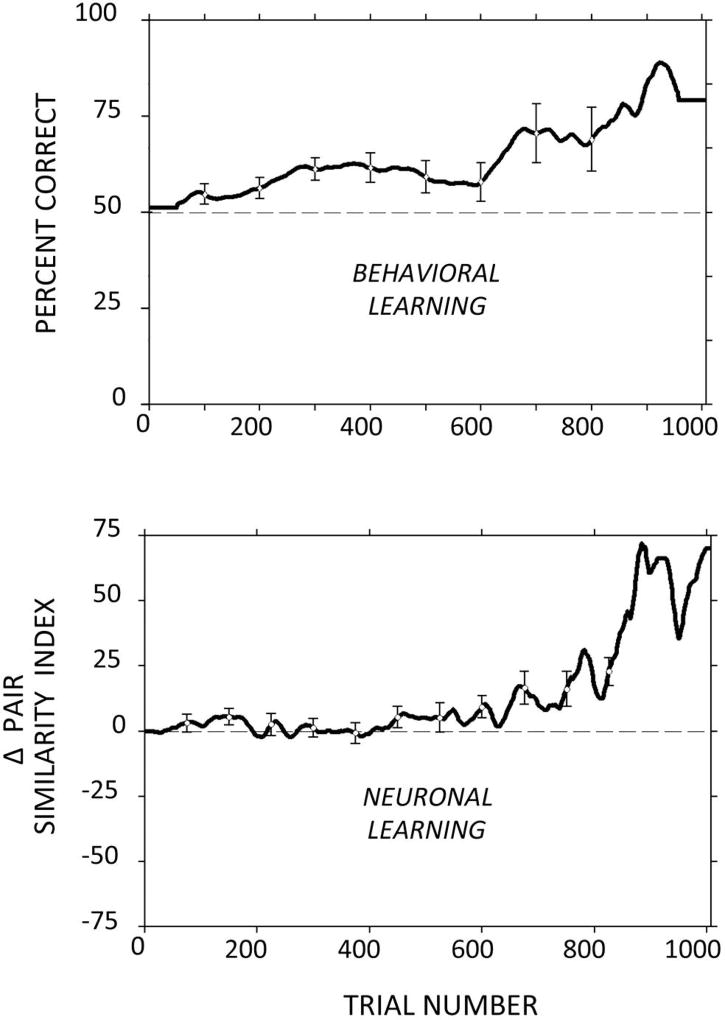

We began by examining how the learning of sensory associations is implemented by neuronal plasticity.34 We hypothesized –in accordance with James’s conjecture (“When two elementary brain-processes have been active together or in immediate succession, one of them, on reoccurring, tends to propagate its excitement into the other”)35–that associations are established through the formation or strengthening of neuronal connections between the independent neuronal representations36 of the paired stimuli. To test this hypothesis, we trained subjects to learn associations between pairs of visual stimuli that consisted of meaningless patterns (“clipart” figures).37 As the subjects acquired the associations, we monitored activity from neurons in the inferior temporal (IT) cortex,38 a region that lies at the pinnacle of the visual processing hierarchy39 (Figure 2) and is known to be critical for object recognition, which relies on memory of prior associations. Neurons in the it cortex respond selectively to complex objects, such as the visual patterns used for this experiment.40 We predicted that as subjects learned new associations between these stimuli, connectivity would increase between neurons that were initially selective for one or the other member of a pair. The result of this change in connectivity, then, should be expressed physiologically as a convergence of the magnitude of the neuronal responses to the paired stimuli. Figure 7 illustrates the average behavioral and neuronal changes that occurred in these experiments. As subjects learned novel visual stimulus associations (Figure 7, top panel), the index of neuronal response similarity (bottom panel) increased, reflecting the expected convergence of responses to paired stimuli. In other words, as the stimuli become symbols for one another by association, the neuronal representations of those stimuli become less distinguishable. We believe that these neuronal changes are the physical manifestations of the newly learned associative memories.

Figure 7. Parallels between Behavioral Acquisition of Learned Associations between Pairs of Visual Stimuli (top panel) and Changes in the Selectivity of Cortical Neurons for the Paired Stimuli (bottom panel).

Top: Average performance as a function of trial number on a task in which subjects were instructed to choose a stimulus that we arbitrarily paired with a cue. For example, if subjects were shown stimulus A, they would be rewarded only for choosing stimulus B in the presence of distracters. Initial performance in this task is always at chance because the subject has no way to predict the pairings we impose. After a few dozen trials, performance begins to increase and ultimately reaches a high level.

Bottom: We predicted that concomitant with behavioral evidence of learning, we would see changes in the visual responses of neurons in the inferior temporal (it) cortex (see Figure 2) to the paired stimuli. Plotted here is the trial-by-trial change in a measure of the similarity of response magnitudes to the paired stimuli (A and B). As learning proceeded, the responses to paired stimuli became more similar to one another and the responses to unpaired stimuli became less similar. We believe that these neuronal response changes reflect ongoing modifications to the local circuitry in the it cortex, through which long-term memory for the learned pairings is achieved.

All data are averaged over many learning sessions, experimental subjects, and cortical neurons. Figure data: Adam Messinger, Larry R. Squire, Stuart M. Zola, and Thomas D. Albright, “Neuronal Representations of Stimulus Associations Develop in the Temporal Lobe during Learning,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 2001): 12239–12244.

Memories consolidated41 in this manner over the course of a lifetime provide the store of “farther facts associated with the object of sensation”: the temporal context needed to interpret sensory events. We thus hypothesized that if the activity of a neuron in the visual cortex underlies perception (as opposed to sensation), that activity should be influenced by the retinal stimulus as well as by information retrieved from the memory store (the cellular locus of stored information in the brain). To test this hypothesis, we first trained subjects to associate pairs of stimuli and then evaluated the responses to individual members of each pair.42 We predicted that the new “meaning” given to a visual stimulus by the learned association would be reflected in a new form of neuronal selectivity for the stimulus.

The stimuli used for this experiment were moving patterns and stationary arrows. Subjects learned that the direction of motion of each pattern was associated with the direction of the arrow. Upward motion, for example, was associated with an upwardly pointing arrow, and so on. We recorded activity from neurons in cortical visual area mt (Figure 2), which are highly selective for motion direction but are normally unresponsive to non-moving stimuli, such as the stationary arrows used in our experiment.43 As expected, mt neurons responded selectively to the direction of pattern motion. After learning the motion/arrow associations, however, many mt neurons also responded selectively to the direction in which the stationary arrow pointed (Figure 9). Moreover, the selectivity seen was entirely predicted by the learned association. That is, if a cell responded best to upward motion, the arrow direction that elicited the largest response was also upward.

Figure 9. Emergent Visual Stimulus Selectivity in Cortical Visual Area mt following Paired Association Learning.

Subjects learned to associate up and down motions with up and down arrows. (A) Neurophysiological data are shown from a representative mt neuron. The top row illustrates responses to four motion directions. Each of the four plots in this row contains a spike raster display (in which each tic mark indicates the occurrence of an action potential) of the neuronal response obtained for each presentation of the stimulus. Each plot also contains a function that represents the average neuronal response rate as a function of time relative to stimulus onset (time = 0). For each plot, the vertical dashed lines correspond from left to right to stimulus onset, motion onset, and stimulus offset. The gray rectangle indicates the analysis window. The cell was highly directionally selective. The responses to downward and leftward motion were far greater than the responses to upward and rightward motion. The bottom row of plots illustrates responses to four static arrows. Plotting conventions are the same as in the upper row. As a consequence of learning, the cell became highly selective for arrow direction. Responses to the downward and leftward arrows are greatest.

(B) Mean responses of the neuron shown in panel A to motion directions (dashed curve) and corresponding static arrow directions (solid curve), indicated in polar format (polar angle corresponds to stimulus direction and radius corresponds to neuronal response rate). Preferred directions for the two stimulus types (dashed and solid vectors) are nearly identical.

Source: Anja Schlack and Thomas D. Albright, “Remembering Visual Motion: Neural Correlates of Associative Plasticity and Motion Recall in Cortical Area mt,” Neuron 53 (2007): 881–890.

In these experiments, the associative training causes the arrow and motion to serve as symbols for one another in the same sense that the graphical pattern mom serves as a symbol for a specific person. The perceptual experience elicited by sensing the arrow naturally includes the things that the arrow symbolizes, which in this case is the motion with which it has been paired. A corollary of James’s axiom about “farther facts associated with the object of sensation” is that perceptual experience includes tangible “images” of the things recalled–images seen in the “mind’s eye.” Indeed, James defined his “general law of perception” as follows: “Whilst part of what we perceive comes through our senses from the object before us, another part (and it may be the larger part) always comes out of our own head.”44 We thus infer that the perceptual experience elicited in our experiments by the arrow includes visual imagery45 of the motion, which is retrieved from the memory store. We furthermore conclude that the selective pattern of activity exhibited by mt neurons upon viewing the stationary arrow underlies imagery of the motion recalled by association.

The conditions of the experiment described above elicit a form of visual imagery in which the thing imagined (motion) differs markedly from the sensory stimulus (arrow). This is the same form of imagery that occurs when we explicitly conjure the face of a friend, the characters and places in a novel, or imagine how the couch would look if we moved it to the other side of the room. But there is another form of imagery that is ubiquitous and largely nonvolitional, in which the thing (or things) recalled by association “matches” the sensory stimulus and is in fact a probabilistic inference about the cause of that stimulus. Harking back to our earlier discussion of the ambiguity of sensory events and the role of context in resolving that ambiguity, we can see that this latter form of imagery is a critical part of the process. This is particularly true under conditions in which the sensory stimulus is impoverished by noise or incompleteness, as is the case for the pattern in Figure 6. In fact, simple consideration of the objects that surround you –a chair that is partially obscured by a table, a glass blurred by glare, scratchy notes on a pad of paper–suggests that your clear and complete perceptual experience of these objects is the result of sensations that have been complemented–fleshed out, if you will–by information provided by memory. As our experiments have shown, that information comes in the form of selective feedback into the visual cortex, which unites retinal signals with imagery signals to yield perceptual experience of probable things.46

Given the ubiquitous, powerful, and implicit nature of this form of imagery, it is perhaps unsurprising that it can be readily manipulated to hijack perception. Indeed, a major category of performance magic relies on priming47 as a form of temporal context. The result is an illusion in which the viewer’s percept of an equivocal sensory event is not the “correct” solution. Similar unconscious priming effects occur under normal (non-magical) circumstances as well: perceptual biases in eyewitness reports or in the interpretation of wooly data (such as x-ray and forensic fingerprint examination and proofreading) are well documented. There are also priming effects on perception that happen with full awareness. Pareidolia48 is the phenomenon in which we perceive coherent and meaningful patterns in response to (recognizably) random sensations, such as clouds that look like animals or foods that resemble Jesus. Finally, there are genres of art, such as impressionism, in which the image rendered–the sensory stimulus–is left intentionally vague in order to allow the perceptual experience to be completed by the viewer’s prior experiences (which art historian E. H. Gombrich evocatively termed “the beholder’s share”).49

In this essay I have defined perceiving as a process by which the fundamental ambiguity of sensation is resolved through the use of contextual cues, which enable identification of the causes of sensation and attributions of meaning. Through examples drawn from our work on the visual cortex, I have illustrated how spatial context influences perception, how temporal context (memory) overcomes sensory noise and incompleteness, and how fundamental properties of the visual world (such as capricious illumination) are embedded in the machinery of our brains (evolutionary context) and lead to perceptual constancies in the face of variable sensory conditions. From these discoveries, it is natural to conclude that a fundamental and generic computation in the cerebral cortex is the transformation from sensory attributes (the retinal image) to attributes of the external environment (the visual scene). While we know that context is used in that computation, and we can identify neuronal signals that reflect the outcome, we currently know very little about the neuronal mechanisms that give rise to these signals. How, for example, is information from memory selectively and dynamically routed back to the visual cortex in a context-dependent manner to complement information arising from the retina? How do neurons that represent visual motion incorporate information about the spatial layout of a visual scene? Identifying these processes presents formidable challenges, to say the least; but a variety of new experimental techniques–many from the fields of molecular biology and engineering– provide much promise for a future mechanistic understanding of perception.

Biography

THOMAS D. ALBRIGHT, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2003, is Professor and Director of the Vision Center Laboratory and the Conrad T. Prebys Chair in Vision Research at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. His work has appeared in such journals as Nature, Science, Neuron, Journal of Neurophysiology, and The Journal of Neuroscience.

endnotes

- 1.Sensory transducers are specialized cellular mechanisms that enable various forms of environmental energy (mechanical, chemical, radiant) to be converted into energy that is communicated within and between neurons. Transduced energy leads to specific sensations. Photoreceptors, for example, transduce energy in the form of light into neuronal energy, which leads to visual sensation.

- 2.John Stuart Mill. Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy and of the Principal Philosophical Questions Discussed in His Writings. New York: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer; 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 3.James William. The Principles of Psychology. Vol. 2. New York: Henry Holt and Co.; 1890. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sully James. Outlines of Psychology, with Special References to the Theory of Education. New York: Appleton; 1888. [Google Scholar]

- 5.James The Principles of Psychology [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid Thomas. In: An Inquiry into the Human Mind, On the Principles of Common Sense. Brookes DR, editor. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press; 1997. p. 1764. [Google Scholar]

- 7.James The Principles of Psychology [Google Scholar]

- 8.The retina is a multilayered sheet of neuronal tissue that lines the back of the eye. Light refracted by the lens is projected onto the retina and is transduced by photoreceptors into neuronal signals. These neuronal signals are enhanced by additional retinal processing to detect contrast and are carried by the optic nerve/tract on to the rest of the brain.

- 9.James The Principles of Psychology [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibid.

- 11.The cerebral cortex is a multilayered and highly convoluted sheet of neuronal tissue that forms the exterior of much of the mammalian brain. It mediates complex sensory, perceptual, and cognitive processes and coordinates voluntary goal-directed behaviors. The cerebral cortex makes up approximately three-quarters of the human brain’s volume, and approximately one-third of the area of the human cerebral cortex is involved in the processing of visual signals.

- 12.Neurons are the major cell type in the brain involved in neuronal communication and computation. Signals are communicated electrically within a neuron via progressive changes in the voltage difference between the inside and outside of the cell. Signals are communicated chemically between neurons via the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft (the microscopic space between neurons), which in turn activate receptors on the next neuron in the sequence. There are approximately one hundred billion neurons in the human brain.

- 13.The receptive field is the part of sensory space that, when stimulated, leads to a change in the activity of a sensory neuron (a neuronal response). In the case of vision, the receptive field of a neuron is defined by the region of visual space that, when stimulated, activates the neuron, and by the sensory attributes of the activating stimulus (such as its direction of motion).

- 14.An action potential is a brief stereotyped neuronal signal that typically sweeps from the cell body along the length of the output process (axon) of a neuron. This neuronal signal results from a rapid, active, and propagating exchange of ions across the cell membrane. An action potential entering the terminus of an axon leads to the release of the neurotransmitter.

- 15.The optic nerve/tract is a bundle of neuronal fibers composed of axons leaving the retina, which carry visual signals up to the rest of the brain. There are approximately one million retinal axons in each optic nerve of the human brain. The nerve becomes the optic tract when it enters the larger mass of the brain.

- 16.Synapse: 1) Noun: A collection of structures that underlies chemical transmission of signals between neurons. It includes specialized cell membranes on pre- and post-synaptic neurons, neurotransmitter substance, vesicles that package and release a neurotransmitter from a pre-synaptic membrane, receptors on a post-synaptic membrane that are activated by a neurotransmitter, and the synaptic cleft (space between pre- and post-synaptic membranes). 2) Verb: To form a synapse.

- 17.The forebrain is the most anterior portion of the vertebrate brain, which includes the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and hypothalamus and is responsible for sensory, perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral processes.

- 18.The lateral geniculate nucleus is a structure in the central portion of the mammalian brain that receives direct input from the retina and distributes visual signals to the cerebral cortex.

- 19.The primary visual cortex (area v1) is the portion of the cerebral cortex that serves as the entry point for visual signals ascending from the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. Area v1 lies on the posterior (occipital) pole of the human cerebral cortex (see Figure 2). Outputs from area v1 extend to a number of secondary and tertiary cortical visual areas in a hierarchical fashion.

- 20.Neurons represent and communicate information synthesized from their inputs in the form of a response, which is manifested and measureable as changes in the frequency (or pattern, in some cases) of action potentials.

- 21.For review, see Albright Thomas D, Stoner Gene R. Contextual Influences on Visual Processing. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2002;25:339–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142900.

- 22.Stoner Gene R, Albright Thomas D, Ramachandran Vilayanur S. Transparency and Coherence in Human Motion Perception. Nature. 1992;344:153–155. doi: 10.1038/344153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stoner Gene R, Albright Thomas D. Neural Correlates of Perceptual Motion Coherence. Nature. 1992;358:412–414. doi: 10.1038/358412a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stoner Gene R, Albright Thomas D. The Interpretation of Visual Motion: Evidence for Surface Segmentation Mechanisms. Vision Research. 1996;36:1291–1310. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Duncan Robert O, Albright Thomas D, Stoner Gene R. Occlusion and the Interpretation of Visual Motion: Perceptual and Neuronal Effects of Context. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:5885–5897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang Xin, Albright Thomas D, Stoner Gene R. Adaptive Surround Modulation in Cortical Area mt. Neuron. 2007;53:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang Xin, Albright Thomas D, Stoner Gene R. Stimulus Dependency and Mechanisms of Surround Modulation in Cortical Area mt. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:13889–13906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1946-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Albright, Stoner Contextual Influences on Visual Processing. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan, Albright, Stoner Occlusion and the Interpretation of Visual Motion: Perceptual and Neuronal Effects of Context. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Albright, Stoner Contextual Influences on Visual Processing. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Binocular disparity cues are subtle differences between the visual images cast in the two eyes that originate from the fact that right and left eyes have overlapping but slightly different views of the world. These visual image differences (“cues”) are physically related to the distance of a stimulus. The perception of distance in human vision is thus informed by these cues.

- 25.Albright, Stoner Contextual Influences on Visual Processing. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142900. see video demonstration of the effect at http://vcl-s.salk.edu/Research/Motion-Integration/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.The middle temporal visual area (area mt) is the visual area of the cerebral cortex that receives direct input from area v1 and lies at an intermediate stage in the hierarchy of processing streams in the visual cortex (see Figure 2). Neurons in area mt are highly responsive to motion in the visual field and their activity underlies visual motion perception. Outputs of area mt control brain regions that mediate eye movements.

- 27.For review, see Albright Thomas D. Cortical Processing of Visual Motion. In: Wallman Joshua, Miles Frederick A., editors. Visual Motion and its Use in the Stabilization of Gaze. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 177–201.

- 28.Sensory attributes are basic elements of sensory experience given by properties of the sensory world. In the case of vision, the attributes of sensation include brightness, color, texture, distance, and motion, as well as size and shape. Combinations of sensory attributes elicit specific perceptual experiences.

- 29.Perceptual constancy is the invariant perception of a visual object across changes in the sensory attributes that are manifested by the object. For example, perceived size is typically constant for a given object despite the fact that retinal size is inversely proportional to viewing distance. Viewing distance, in this case, is computed from visual depth cues, such as binocular disparity and linear perspective, and serves to normalize perceived size.

- 30.Albright Thomas D. Form-Cue Invariant Motion Processing in Primate Visual Cortex. Science. 1992;255:1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1546317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stoner Gene R, Albright Thomas D. Motion Coherency Rules are Form-Cue Invariant. Vision Research. 1992;32:465–475. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90238-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chaudhuri Avi, Albright Thomas D. Neuronal Responses to Edges Defined by Luminance vs. Temporal Texture in Macaque Area v1. Visual Neuroscience. 1997;14:949–962. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800011664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albright Form-Cue Invariant Motion Processing in Primate Visual Cortex. doi: 10.1126/science.1546317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Associative learning is the simplest and most common form of learning, in which different sensations, symbols, concepts, or events are linked together in memory by virtue of their proximity in time and/or reinforcement.

- 33.Memory retrieval is the process of accessing information stored in memory and making it available for use in perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral processes.

- 34.In this context, plasticity refers to experience-dependent changes in the stimulus attributes that are encoded by a neuron.

- 35.Albright Form-Cue Invariant Motion Processing in Primate Visual Cortex. doi: 10.1126/science.1546317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The unique stimulus attributes that lead to a response from a neuron (a change in neuronal activity) define the information that is symbolically represented by the neuron. For example, a visual neuron that responds selectively to a particular direction of motion in its receptive field is said to “represent” that direction of motion.

- 37.Messinger Adam, Squire Larry R, Zola Stuart M, Albright Thomas D. Neuronal Representations of Stimulus Associations Develop in the Temporal Lobe during Learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:12239–12244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211431098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The inferior temporal (it) cortex is the area of the cerebral cortex that corresponds to the highest stage of purely visual processing. The it cortex is located on the inferior convexivity of the temporal lobe in primates (see Figure 2) and plays a central role in visual object recognition. Neurons in the it cortex represent complex collections of stimulus attributes that correspond to behaviorally meaningful objects, such as faces. it neurons exhibit experience-dependent changes in their receptive field properties during visual associative learning, and those changes constitute the cellular trace of the associative memory.

- 39.The visual processing hierarchy is a succession of visual processing stages leading, for example, from the retina, through the thalamus, to the primary visual cortex, and on to secondary and tertiary cortical visual areas. Each stage in the hierarchy selectively integrates information from the preceding stage, yielding increasingly complex neuronal representations as signals move up through the hierarchy.

- 40.Desimone Robert, Albright Thomas D, Gross Charles G, Bruce Charles J. Stimulus Selective Properties of Inferior Temporal Neurons in the Macaque. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1984;8:2051–2062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-08-02051.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Memories are initially encoded in a form that has limited duration and capacity and is labile, decaying quickly with time and easily disrupted by other perceptual or cognitive processes. Through cellular and molecular events that play out over time, the contents of short-term memories may be encoded and consolidated into long-term memory, which is more enduring and of greater capacity.

- 42.Schlack Anja, Albright Thomas D. Remembering Visual Motion: Neural Correlates of Associative Plasticity and Motion Recall in Cortical Area mt. Neuron. 2007;53:881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albright Cortical Processing of Visual Motion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.James The Principles of Psychology [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visual imagery is the subjective experience that occurs when memories of perceptual experiences are retrieved. Imagery of an object is similar to a percept of the object resulting from retinal stimulation; both are mediated by the same neuronal structures and events in the visual cortex. Explicit imagery is volitional (for example, picture your car in your mind’s eye). Implicit imagery is cued by association with a sensory stimulus and serves to augment perceptual experience based on expectations, in the face of noisy or incomplete sensory signals.

- 46.For review, see Albright Thomas D. On the Perception of Probable Things: Neural Substrates of Associative Memory, Imagery, and Perception. Neuron. 2012;74:227–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.001.

- 47.After two sensory stimuli have become associated with one another, presentation of one stimulus leads to enhanced (faster, more accurate) processing of the other. This phenomenon is known as priming.

- 48.Pareidolia is a phenomenon of visual imagery in which expectations derived from prior experience cause random patterns to be perceived as meaningful objects.

- 49.Gombrich Ernst H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]