Abstract

Purpose:

This article introduces the importance and nature of the role of the nurse scientist as a knowledge broker.

Design:

A systematic literature review was completed using a modified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) appraisal tool[JC1] to trace the emergence and characteristics of the knowledge broker role across disciplines internationally and in the United States.

Methods:

Salient publications were identified using PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Sociological Abstracts, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, as well as hand searches and searches of the grey literature. Authors used these resources to define the knowledge broker role and with their role-related experiences developed the Thompson Knowledge Brokering Model.

Findings:

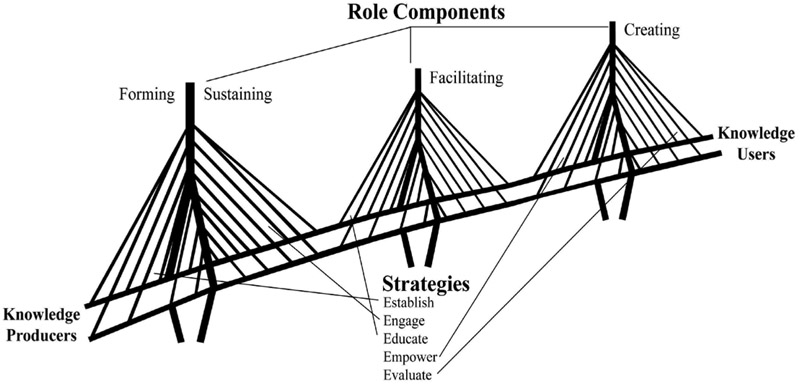

A knowledge broker is one who connects science and society by building networks and facilitating opportunities among knowledge producers and knowledge users. The knowledge broker role includes three components: forming and sustaining partnerships; facilitating knowledge application; and creating new knowledge. There are five major strategies central to each role component: establish, engage, educate, empower, and evaluate.

Conclusions:

The knowledge broker role has been increasingly recognized worldwide as key to translating science into practice and policy. The nurse scientist is ideally suited for this role and should be promoted worldwide. The Thompson Knowledge Brokering Model can be used as a guide for nurse scientists.

Keywords: Knowledge broker, knowledge brokering, nurse scientist, research translation

“The perspective of the nurse scientist is vital to identifying the most effective strategies to accelerate translational research” (Grady, 2010, p. 164). Knowledge brokering allows the nurse scientist to capitalize on opportunities to lead collaborative research teams and advance a culture of health, key recommendations in the Future of Nursing (Institute of Medicine, 2010). The importance and nature of the role of the nurse scientist as a knowledge broker is introduced in this article. The role of the knowledge broker is described as it emerged over time and across disciplines internationally and its relatively recent expansion within the United States. A critique of existing practice models and implementation strategies, strengths, and challenges are based on a systematic review of the research and grey literature, with insights built upon prior work (Pennell et al., 2013) and continued experience in population-based environmental health research conducted in collaboration with indigenous peoples. Three components to the knowledge broker role and five strategies that the nurse scientist can employ when translating research and engaging stakeholders—scientists (i.e., knowledge producers) and nonscientists (i.e., knowledge users)—are introduced. This work expands on the involvement and long-standing interest of nurse scientists in translational research (Polit & Beck, 2016).

Scientific research should not sit on academic bookshelves or be quarantined in laboratories. Yet, it takes an average of 17 years for research to be integrated into practice and policy (Morris, Wooding, & Grant, 2011). Regardless of discipline, scientists are expected to disseminate, translate, and integrate their research into broader contextual and interdisciplinary perspectives to inform practice, policy, and decision making, all the while ensuring the information is understandable and that individuals understand the research (American Association of Colleges of Nursing Task Force, 1999).

For scientific knowledge to be usable and useful, it must have adequacy, value, legitimacy, and effectiveness on a realistic timescale (Clark & Majone, 1985). This requires scientific knowledge to be synthesized, exchanged, and applied within specific social, institutional, and human constructs (Greenhalgh & Wieringa, 2011). Knowledge users need scientific research to resolve issues of their concern. Knowledge users include intra- and interdisciplinary professionals, regulators, and legislators, as well as leaders and members of various organizations and communities. For knowledge users, the amount and scope of scientific information can be seemingly overwhelming and often incomprehensible—what does it mean? As a result, many meaningful conversations and decisions about health care and policy are neither science nor evidence based. This leads to less than informed decisions and many unintended consequences that impact health adversely (Culley & Highey, 2008).

The biggest challenges for knowledge producers and knowledge users are issues that are complex, particularly where there is scientific or regulatory uncertainty; where contextual and scientific knowledge conflict; and multiple stakeholders (i.e., scientists and nonscientists) are involved (Braun & Kropp, 2010). These conditions require a “team science” approach that creates convergence across disciplines and communities (Sharp et al., 2011). This interdisciplinarity creates challenges in and of itself. While different disciplines may use the same terms, their definitions are often different, as are the methods by which each discipline measures these concepts. Additionally, each discipline may examine disparate outcomes (Thompson & Schwartz Barcott, 2017). The knowledge broker role was designed to meet these challenges. Not only are nurse scientists adept at conducting basic and applied research, but they are knowledgeable in promoting efficient and effective translation and utilization of research so that it is meaningful and useful in various contexts to all stakeholders. Thus, nurse scientists are ideally suited for the knowledge broker role.

Design

A modified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) appraisal tool (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009) was employed to conduct a systematic review of the literature aimed at tracing the emergence and characteristics of the knowledge broker role across disciplines internationally and in the United States. This approach included the identification and critical evaluation of existing knowledge-brokering models that led to the clarification and refinement of an innovative model.

Method

Salient publications were identified using PubMed (1980–2017) with the key words “knowledge broker” OR “knowledge brokering” in any field with filters (abstract available and English), resulting in 92 citations for review. A search of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1994–2017), Sociological Abstracts (1989–2017), and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (1979–2017) using the same key words and filters resulted in 30 and 105 abstracts and 19 doctoral dissertations, respectively. Duplicate citations were eliminated across databases. After reading each abstract to determine if a knowledge broker or knowledge brokering was used in the context of role development germane to health, health care, or policy, a total of 83 articles and 12 dissertations were categorized by discipline and area of specialty, then reviewed in detail by each author independently. Subsequently, the authors met for in-depth discussions of the analyses until agreement was reached on the level of intersubjectivity of existing implicit and explicit definitions, and role descriptions, models, and points needing further clarification or inclusion in a refined definition or description or model (Table S1). Additionally, hand searches were conducted to document the evolution of the knowledge broker role and knowledge-brokering strategies. A broader search of grey literature followed using the additional related terms implementation science, program evaluation, capacity building, evidence-informed decision making, and team science. Authors used these resources and their role-related experiences to develop a comprehensive definition of the knowledge broker, including role components, and knowledge-brokering strategies for the nurse scientist specifically.

Findings

Knowledge brokering is a worldwide phenomenon. The World Health Organization (2004) recognized the need for knowledge-brokering systems to strengthen the relationship between policy-relevant research and evidence-based policy. There is a knowledge brokers’ forum (http://www.knowledgebrokersforum.org) with 964 members worldwide. Publications reviewed for this article represented authors from six continents and 28 countries. Of note, 35% of the articles reviewed were from Canadian authors. Since 1996, the practice of knowledge brokering has been a conscious and concerted effort within Canada’s health system (Canadian Health Systems Research Foundation, 2003). By comparison, the role of the knowledge broker has been slower to emerge in the United States, even though government agencies have been promoting and funding efforts to translate scientific research into practice and policy (Westfall, Mold, & Fagnan, 2007).

Evolution of the Knowledge Broker Role

As early as the 1950s, anthropologists described a culture broker or cultural broker as an intermediary who promoted interactions of disparate subcultures (Lindquist, 2015). In the 1960s, library scientists referred to an information liaise, who provided customized services to scientific and technical researchers (Tennant et al., 2001). With the dawn of the Information Age (1970s), there was a corresponding rise of the information broker, who facilitated identification of information, data collection, and data sharing (Christozov & Toleva-Stoimenova, 2014). A boundary spanner was described first by social scientists in the late 1950s as one who crossed or spanned two social groups (March & Simon, 1958). More recently, a boundary spanner has evolved more broadly as a systems thinker with the ability to move across and through formal and informal organizational structures (Cooper & Fox, 2013). A policy broker linked knowledge production, policymaking, and economic development through enhancing the translation of research into use for the benefit of the poor (Kingiri & Hall, 2011). A social entrepreneur pursued opportunities to deliver innovative products or services in a socially responsible way in order to promote cohesion and inclusion, particularly of marginalized populations (Spruijt, n.d.). There are numerous job titles associated with knowledge brokering, with each job title inferring a particular approach to brokering knowledge. Kitson and Harvey (2016) advocated for nurse clinicians to be facilitators who enabled and encouraged individual clinicians to adopt new evidence-based practices using action learning techniques.

Burt (1992) was among the first to use the term knowledge brokering to describe what an entrepreneur does to network individuals with complementary resources or information. In this context, this individual built social capital from developing benefit-rich networks and a reliable flow of useful information, thus providing individuals or organizations with a competitive advantage in market transactions. The knowledge broker model introduced in this article was built upon Burt’s work.

Though the role of the knowledge broker is not new, it is a relatively novel concept for nurse scientists engaged in translational research. In the two nursing articles found through this search, Jaja, Gibson, and Quarles (2013) and Yost et al. (2014) emphasized the importance of the nurse scholar as a knowledge broker when connecting diverse stakeholders in evidence-informed decision making, though there was neither in-depth discussion of the role nor introduction of a practice model. Additionally, there remained conceptual uncertainty around the concept of the knowledge broker, hence the need for an explicit definition.

Definition of a Knowledge Broker

Based on the above systematic review and analysis of the interdisciplinary literature, the following definition was developed: A knowledge broker is one who connects science and society by building networks and facilitating opportunities between and among knowledge producers and knowledge users to share knowledge, learn from it, apply it meaningfully in research, practice, education, and policy, and to create new knowledge together.

Evaluation of Existing Knowledge-Brokering Models

Existing models have been critiqued elsewhere (Davies, Powell, & Nutley, 2015; Davison, Ndumbe-Evoh & Clement, 2015). Four areas were not addressed or articulated sufficiently: stakeholder engagement, resources, and evaluation, and engaging nonscientists, specifically, nonprofessional knowledge users. Overwhelmingly, frameworks described the processes that occurred around knowledge creation, flow, and application. While these frameworks coalesced around one of three strategies (i.e., contexts in which knowledge was produced, used, and mediated; interactions among actors; and organizational infrastructure), the vital importance of sustaining relationships over time was addressed rarely. Most of these models did not begin with the requisite relationship building among the knowledge producers, knowledge users, and knowledge broker. There was discussion as to whether each of these roles was represented by different individuals. If so, this would require extensive collaboration, a potentially complicated and challenging process. Implicit in these descriptions was that the knowledge broker was not a knowledge generator. Additionally, most models were not explicit about the actions or resources required to succeed, especially around planning for change. Outcomes of knowledge utilization were not defined clearly or prospectively. Dagenais, Laurendeau, and Briand-Lamarche (2015) identified three outcome categories: direct use of research results; research results that changed opinion but not practice or policy; and research that was used to legitimize and sustain a priori actions or decisions. Alternatively, a logic model could be used to evaluate the effectiveness and efficacy of a project, whether a planned activity was implemented as it was intended, or to determine if a specific activity had the desired result. Depending on the activity and timeline, short- and long-term impacts could be assessed as well (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, 2012). Strategies for knowledge brokering when the knowledge users are nonscientists (i.e., vulnerable and marginalized populations) were virtually absent from the literature. Those articles that focused on building and sustaining academic–community partnerships (including those studies involving citizen science) did not address specifically the role of a knowledge broker (e.g., Korfmacher, Pettibone, Gray, & Newman, 2016). The following knowledge broker model was developed to address these weaknesses specifically but not exclusively.

The Thompson Knowledge Brokering Model

In this model (Figure 1), there are three components to the knowledge broker role: (a) forming and sustaining mutually beneficial partnerships with and among scientists, practitioners, policymakers, or the public; (b) facilitating these stakeholders’ application of knowledge, analyses, and evaluation of scientific and contextual knowledge; and (c) creating new knowledge of value and utility to all stakeholders.

Figure 1.

The Thompson Knowledge Brokering Model.

There are five major strategies that are central to each role component: (a) establish, (b) engage, (c) educate, (d) empower, and (e) evaluate. These strategies represent a nonlinear and reiterative process that evolves over time. Implementing each of these strategies can be tailored specifically to knowledge producers or knowledge users, while others span across all stakeholders. These strategies are supported by community-based participatory research approaches and mixed (quantitative and qualitative) methodologies (D’Alonzo, 2010).

A knowledge broker must employ these innovative multitiered collaborative strategies to form complementary transdisciplinary research teams, establish long-term mutually beneficial synergistic partnerships, facilitate multidirectional knowledge exchanges, implement practice-based evidence, and build capacity among stakeholders. To illustrate this knowledge broker model with its role components and strategies in practice, an example is taken from the first author’s (M.R.T.’s) experience as a knowledge broker in an ongoing academic–government–community partnership in which the she was co-leader for community engagement and the principal investigator (PI). This ongoing work illustrates the complexities of the knowledge broker role. Some strategies discussed have been employed, while others are in planning or process (Tables 1–3).

Table 1.

Examples of Strategies for Working With Knowledge Producers and Knowledge Users by Knowledge Broker Role Component

| Strategies | Forming/sustaining mutually beneficial partnerships with and among scientists, practitioners, policymakers, and/or the public | Facilitating these stakeholders’ application, analyses, and evaluation of scientific and contextual knowledge | Creating new knowledge of value and utility to all stakeholders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | |

| Establish | ||||||

| Identify potential stakeholder(s) | ||||||

| Identify individuals in relevant disciplines | Identify individual(s) who are respected and trusted by stakeholder(s) as first contact | Request meeting(s) to discuss ideas and propose potential projects | Request introduction to gatekeeper(s) through individual(s) who are respected and trusted by these gatekeeper(s) | |||

| Gauge interest and availability of these individuals to participate as well as adequacy and availability of resources and key personnel | Meet gatekeepers(s) and begin protracted dialogue | Build credibility among stakeholders | Build trust and mutual respect among stakeholders | |||

| Be flexible, adaptable, and politely persistent | Maintain equity among stakeholders | |||||

| Be patient: think long term partnerships (years) | ||||||

| Identify stakeholders’ issues of concern | ||||||

| Conduct key informant interviews | Gain in-depth understanding about ongoing program(s) of research | Conduct focus groups | Create a shared vision | Create a shared vision | ||

| Identify knowledge producers’ strengths | Identify knowledge users’ strengths | Manage expectations of knowledge producers | Manage expectations of knowledge users | Propose making decisions through consensus | Propose making decisions through consensus | |

| Build networks of stakeholders | ||||||

| Create (external) advisory board | Create (community) advisory board | |||||

| Assemble complementary team(s) of scientists from different disciplines | ||||||

| Coalesce around complementary multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary project(s) | ||||||

| Sustain networks | ||||||

| Facilitate regularly scheduled meetings | Facilitate regularly scheduled meetings | Work collaboratively | Work collaboratively | |||

| Summarize periodic performance evaluation of knowledge producers by knowledge users | Summarize periodic performance evaluation of knowledge users by knowledge producers | Seek opportunities for continued dialogue | Seek opportunities for continued dialogue | Build collegiality | Build collegiality | |

| Engage | ||||||

| Recognize cultural norms and practices of stakeholders | ||||||

| Identify cultural framework from knowledge producers’ perspective(s) | Identify cultural framework from knowledge users’ perspective(s) | Seek clarity and consensus among knowledge producers | Seek clarity and consensus among knowledge users | |||

| Read, listen, ask, learn, explore | Read, listen, ask, learn, explore | Develop experiential learning opportunities for knowledge producers to learn about the knowledge users where appropriate | Develop experiential learning opportunities for knowledge users to learn about the knowledge producers where appropriate | |||

| Encourage stakeholder feedback | Encourage stakeholder feedback | |||||

| Attend and participate in stakeholder events | Attend and participate in stakeholder events | |||||

| Identify health disparities and social justice issues | ||||||

| Employ cultural self-reflexivity | ||||||

| Identify cultural values and goals of diverse disciplines | Identify cultural lenses (emic/etic) | Acknowledge differences and commonalities | Acknowledge differences and commonalities | Establish a common set of values and goals | Establish a common set of values and goals | |

| Explore, learn, declare aloud | ||||||

| Recognize interstitiality of K* role in academia | Identify existing and potential power differentials | |||||

| Integrate plurality of perspectives | Incorporate cultural practices of knowledge producers into activities as appropriate | Incorporate cultural practices of knowledge users into activities as appropriate | ||||

| Identify decision-making processes of each stakeholder | ||||||

Table 3.

Examples of Strategies for Working With Knowledge Producers and Knowledge Users by Knowledge Broker Role Component

| Strategies | Forming/sustaining mutually beneficial partnerships with and among scientists, practitioners, policymakers, and/or the public | Facilitating these stakeholders’ application, analyses, and evaluation of scientific and contextual knowledge | Creating new knowledge of value and utility to all stakeholders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | |

| Educate | ||||||

| Facilitate multidirectional knowledge exchanges among these stakeholders (continued) | ||||||

| Request knowledge generators present progress of ongoing and new research | Maintain a balance across all stakeholders’ needs | Encourage participation and dialog | Foster synergy among stakeholders | |||

| Examine practice-based evidence | Examine evidence-based practices | Pursue new opportunities as they arise | Use diverse methodologies to enhance quality of exchanges | |||

| Assist stakeholders with applying knowledge in appropriate contexts | ||||||

| Identify contexts in which research may be used | Raise awareness of problem(s) and potential solution(s) | Assist knowledge generators with conducting research as appropriate | ||||

| Extrapolate potential implications | Present content in context | Summative or comprehensive reviews | Apply, analyze and evaluate research | Aim collective efforts at affecting population level changes | ||

| Use terms and definitions consistently | Use terms and definitions consistently | Hold classes during sentinel events | Build an infrastructure for communication among groups/individuals | |||

| Empower | ||||||

| Build capacity among stakeholders for evidence-informed participatory decision making | ||||||

| Identify and capitalize on knowledge users’ assets | Raise critical consciousness regarding issues of concern, health impacts, and need for social action | |||||

| Offer opportunities for knowledge users to participate at varying levels | Identify and mentor leaders | |||||

| Assist stakeholders in evidence-informed participatory decision making | ||||||

| Employ organization and community-based participatory methodologies | Form coalitions among knowledge users when appropriate | |||||

| Assist stakeholders with integrating best available research-based evidence into practice and policy | ||||||

| Summarize risk-benefit analyses and relative risks, identify uncertainties | Initiate systems level changes | |||||

| Advocate for social change | Celebrate successes | Sustain systems level changes | ||||

| Work collaboratively to create new transdisciplinary knowledge | ||||||

| Ensure succession: identify future nurse scientists as knowledge brokers | Ensure legacy and continuity identify future stewards/leaders | Share results with others including processes and lessons learned | Encourage development of new research based on users’ needs | Imagine the knowledge broker role as the catalyst for change | ||

| Evaluate | Foster opportunities for others to build upon these successes | |||||

| Identify resources, processes, outcomes, and impacts with timelines early | ||||||

| Select evaluation methods/tools | Select evaluation methods/tools | Employ mixed methodologies | Create logic model(s) | |||

| Reflect on stakeholders’ experiences, observations, and interpretations | Conduct periodic review | Describe ongoing documentation strategies | ||||

| Define knowledge utilization outcomes | ||||||

| Document use of research results | Discuss research results and translational efforts | |||||

| Examples of research result in changing opinion but not practice or policy | ||||||

| Examples of research were used to legitimize and sustain a priori action/decision | ||||||

| Use appropriate disciplinaries’ lens in selecting outcomes and evaluation methods | Use cultural lens in selecting outcomes and evaluation methods as appropriate | Formulate a strategic evaluation plan | Incorporate recommendations into policy and practice | |||

| Compare to baseline | Conduct periodic reviews | |||||

| Measure impact on research, research trajectories, and related policies | Measure impact on health, health disparities, and related policies and individual behaviors when appropriate | |||||

1. Establish.

The knowledge broker identifies potential stakeholders (i.e., knowledge producers and knowledge users). In the example, each of six community partners was closely affiliated with a specific Superfund National Priority List or Brownfield site situated on or adjacent to critical waterways. The knowledge broker identifies stakeholders’ issues of concern, thereby fusing purpose and direction with meaning and utility (Armstrong et al., 2013). The knowledge broker supports the technical needs of those impacted by these contaminated sites by working with residents, tribal members, legislators, and regulators regarding the potential health impacts of complex exposures to contaminants. The knowledge broker assures that the academic center’s research is used to inform real decisions and priorities, assess real problems, develop programs and policies, facilitate their implementation, and measure outcomes. Often, Native tribes rebuff offers of assistance from federal, state, and local government agencies and local universities. In the example, a co-PI with Native heritage and active involvement in local and regional Native-American events facilitated the introduction of the knowledge broker to the tribe that led to a partnership between the academic research center and the tribe. At this stage, the knowledge broker builds and subsequently sustains two separate networks of stakeholders—knowledge producers and knowledge users (Ahmed et al., 2016). A knowledge broker connects the academic center’s research to real public health issues by integrating the scientific knowledge of the center’s researchers with the contextual knowledge of community and tribal members. These efforts enhance the center’s research agenda by providing a source of community-based information that is relevant and valuable to the center’s planning. An active advisory board with community representation was created and continues to be nurtured.

2. Engage.

The knowledge broker recognizes stakeholders’ cultural norms and practices and employs cultural self-reflexivity (Harding et al., 2012). In the example, complex environmental contamination within the contexts of environmental justice required “team science” that included multidisciplinary academic researchers, state and federal regulators, tribal government officials, educators, artists, and community and tribal members of all ages. The knowledge broker establishes mutually beneficial and synergistic partnerships with these stakeholders. Once introduced to the tribal director of community planning and natural resources, the knowledge broker built and nurtured a collaborative working relationship and jointly developed a plan to address the tribe’s critical environment and environmental health–related needs. A memorandum of understanding and a work plan was developed jointly. The knowledge broker nurtures long-term mutually beneficial synergistic partnerships with stakeholders. In the example, this relationship-building process took approximately 3 years before the research project was launched.

3. Educate.

At this point in the project, the plan is that the knowledge broker will facilitate multidirectional knowledge exchanges among the knowledge producers and knowledge users. The knowledge broker will assist stakeholders in applying, analyzing, and evaluating knowledge in appropriate contexts (Bannister & O’Sullivan, 2013).

4. Empower.

In the example, the knowledge broker will build capacity among stakeholders for evidence-informed participatory decision making (Jernigan, Jacob, The Tribal Community Research Team, & Styne, 2015) and assist stakeholders with integrating best available research-based evidence into practice and policy. The knowledge broker will be working collaboratively with knowledge generators and knowledge users to create new transdisciplinary knowledge whenever possible and appropriate.

5. Evaluate.

In the example, the knowledge broker identified resources, processes, outcomes, and impacts with timelines early in the project. It was important to define knowledge utilization outcomes early in the process as well (LaFrance, Nichols, & Kirkhart, 2012). Capturing the translational narrative as it unfolds over time will assist with tracking process and progress (Pettibone, 2017).

Conclusions

The knowledge broker role has been increasingly recognized worldwide as the key to translating science into practice and policy. The nurse scientist is ideally suited for this role. In this article, the knowledge broker was defined as a person who connects science and society by building networks and facilitating opportunities between and among knowledge producers and knowledge users to share knowledge, learn from it, apply it meaningfully in research, practice, education, and policy, and to create new knowledge together. The Thompson Knowledge Brokering Model was presented and included three major components (forming and sustaining partnerships; facilitating knowledge application; and creating new knowledge) and five strategies (establish, engage, educate, empower, and evaluate) that the nurse scientist can employ when translating research and engaging stakeholders.

Limitations

There were three limitations. Characteristics or attributes found among successful knowledge brokers were not elaborated. Based on the authors’ experiences, individuals gravitate to this role because of their unique blend of competencies, skills, and experience. Secondly, it was impossible to cover fully the complexity of the subject. The large number of actors involved made creating this model particularly difficult. Finally, examples were not exhaustive in order to provide flexibility and allow for alternative strategies to be used.

Implications

The role of the nurse scientist as a knowledge broker should be promoted worldwide. The knowledge broker role needs to be integrated into advanced practice curricula (i.e., doctoral studies) to teach the necessary skills and provide experiential learning. The knowledge broker role should be developed in healthcare organizations. There is much potential for the nurse scientist in the role of a knowledge broker to change the availability and access to information, improve health literacy, and reduce health disparities among varying communities, particularly within the contexts of social justice and empowerment (O’Fallon, Wolfe, Brown, Deary, & Olden, 2003). Knowledge broker strategies can be incorporated when developing health policy. More outcome research is needed. Lastly, mechanisms for funding should be promoted strongly among agencies to provide monies for research translation and community engagement.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Examples of Strategies for Working With Knowledge Producers and Knowledge Users by Knowledge Broker Role Component

| Strategies | Forming/sustaining mutually beneficial partnerships with and among scientists, practitioners, policymakers, and/or the public | Facilitating these stakeholders’ application, analyses, and evaluation of scientific and contextual knowledge | Creating new knowledge of value and utility to all stakeholders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | Working with knowledge producers | Working with knowledge users | |

| Engage | ||||||

| Establish mutually beneficial and synergistic partnerships with stakeholders | ||||||

| Obtain a memorandum of understanding issued by each stakeholder stating common principles | Obtain a memorandum of understanding issued by each stakeholder stating common principles | Accommodate differences in time frames of professionals and affiliate organizations | Accommodate differences in conceptual time frame of knowledge users | Create working relationships across stakeholders | ||

| Develop jointly a scope of work co-signed by principles: 1. Objectives, plan, timeline 2. Roles and responsibilities of co-investigators 3. Address institutional changes 4. Oversight 5. IRB certification and training requirements 6. Communications 7. Data sharing, ownership and release-confidentiality, research results sharing plan, copyrights, dispute resolution 8. Equitable payments to stakeholders 9. Cancellation clause |

Develop jointly a scope of work co-signed by principles: 1. Objectives, plan, timeline 2. Roles and responsibilities of co-investigators 3. Address institutional changes 4. Oversight 5. IRB certification and training requirements 6. Communications 7. Data sharing, ownership and release-confidentiality, research results sharing plan, copyrights, dispute resolution 8. Equitable payments to stakeholders 9. Cancellation clause |

Create strategic plan that reflects short-term achievable milestones while working towards longer-term goals | ||||

| Obtain letters of support from stakeholder organizations | Obtain written declarations from organizational/community leaders in support of project | Identify and engage “champions” selectively | ||||

| Recruit knowledge generator(s) to be co-investigator(s) | Recruit select knowledge user(s) to be co-investigator(s) | Secure extramural funding for sustaining projects | Secure extramural funding for sustaining partnerships | Collect baseline data and create metrics for short-term and long-term project outcomes and evaluation of process (see also “Evaluation”) | Collect baseline data and create metrics for short-term and long-term project outcomes and evaluation of process (see also “Evaluation”) | |

| Recruit students as research assistants | Recruit and involve knowledge user(s) throughout research process | Pay knowledge users who are involved in conducting the research | ||||

| Pay study participants | ||||||

| Nurture long-term mutually beneficial and synergistic partnerships with stakeholders | ||||||

| Schedule onsite visits regularly with co-investigators | Schedule onsite visits regularly with co-investigators | Schedule meetings regularly with team | ||||

| Monitor and verify delivery on all commitments | Foster synergy among all stakeholders | |||||

| Educate | ||||||

| Facilitate multidirectional knowledge exchanges among these stakeholders | ||||||

| Request or generate compilation on state of the sciences across relevant disciplines (e.g., summative reviews, comprehensive reviews, meta-analyses, or meta-syntheses) | Knowledge users present issues of concern and needs for (new) knowledge | Semi-annual or annual retreats for knowledge producers and knowledge users to listen to each other | ||||

| Request or summarize scientific facts and weights-of-evidence for knowledge users | Ensure equitable access to information | Promote coherent and effective communication across all stakeholders | Assemble transdisciplinary teams of knowledge producers and users | |||

Note. IRB = institutional review board.

Clinical Relevance: (a) Facilitate translation of useful research to practice and policy. (b) Connect stakeholders through meaningful engagement.

Clinical Resource.

Knowledge Broker Forum. http://www.knowledgebrokersforum.org

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Grant 2P42ES013660–11 through Brown University’s Superfund Research Program; NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant U54GM115677 through Advance Center for Clinical Translational Science; and the College of Nursing at the University of Rhode Island. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH, NIEHS, NIGMS, or other funding agencies.

References

- Ahmed SM, Maurana C, Nelson D, Meister T, Young SN, & Lucey P (2016). Opening the black box. Project Muse - Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education and Action, 10(1), 7–8. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing Task Force. (1999). Defining scholarship for the discipline of nursing. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/publications/position/defining-scholarship [PubMed]

- Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, Anderson L, Moore L, Petticrew M, . . . Swinburn B (2013). Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: Intervention design and implementation plan. Implementation Science, 8, 121. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister J, & O’Sullivan A (2013). Knowledge mobilization and the civic academy: The nature of evidence, the roles of narrative and the potential of contribution analysis. Journal of the Academy of Social Sciences, 8(3), 249–262. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2012.751497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun K, & Kropp C (2010). Beyond speaking truth? Institutional responses to uncertainty in scientific governance. Science, Technology & Human Values, 35(6), 771–782. doi: 10.1177/0162243909357916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Health Systems Research Foundation. (2003). The theory and practice of knowledge brokering in Canada’s health system. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Christozov D, & Toleva-Stoimenova S (2014). The role of information brokers in knowledge management. Journal of Applied Knowledge Management, 2(2), 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WC, & Majone G (1985). The critical appraisal of scientific inquiries with policy implications. Science, Technology and Human Values, 10(3), 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, & Fox JL (2013). Boundary-spanning in organizations: Network, influence and conflict. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Culley MR, & Highey J (2008). Power and public participation in a hazardous waste dispute: A community case study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 99–114. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9157-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais C., Laurendea MC., & Briand-Lamarch M. (2015). Knowledge brokering in public health: A critical analysis of the results of a qualitative evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 53, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alonzo KT (2010). Getting started in CBPR—Lessons in building community partnerships for new researchers. Nursing Inquiry, 17(4), 282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00510.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies HTO, Powell AE, & Nutley SM (2015). Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: Learning from other countries and other sectors—A multimethod mapping study. Health Services and Delivery Research, 3(27), 1–190. doi: 10.3310/hsdr03270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison CM, Ndumbe-Eyoh S, & Clement C (2015). Critical examination of knowledge to action models and implications for promoting health equity. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 49–60. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0178-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady PA (2010). Translational research and nursing science. Nursing Outlook, 58, 164–166. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, & Wieringa S (2004). Is it time to drop the “knowledge translation” metaphor? A critical literature review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104, 501–509. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A, Harper B, Stone D, O’Neill C, Berger P, Harris S, & Donantuto J (2012). Conducting research with tribal communities: Sovereignty, ethics and data-sharing issues. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 6–10. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). Report brief: The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Retrieved February 26, 2018, from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Jaja C, Gibson R, & Quarles S (2013). Advancing genomic research and reducing health disparities: What can nurse scholars do? Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 45(2), 202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01482.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VB-B, Jacob T, The Tribal Community Research Team, & Styne D (2015). The adaptation and implementation of a community-based participatory research curriculum to build tribal research capacity. American Journal of Public Health, 105(Suppl. 3), S424–S432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingiri A, & Hall A (2011). Dynamics of biosciences regulation and opportunities for biosciences innovation in Africa: Exploring regulatory policy brokering. Maastricht, The Netherlands: United Nations University. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson AL, & Harvey G (2016). Methods to succeed in effective knowledge translation in clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48(3), 294–302. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher KS, Pettibone KG, Gray KM, & Newman OD (2016). Collaborating for systems change: A social science framework for academic roles in community partnerships. New Solutions, 26(3), 429–457. doi: 10.1177/1048291116662680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance J, Nichols R, & Kirkhart KE (2012). Culture writes the script: On the centrality of context in indigenous evaluation. Context, 135, 59–74. doi: 10.1002/ev.20027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist J (2015). The anthropology of brokers and brokerage In Wright J (Ed.), International encyclopedia of social and behavioral science (2nd ed., pp. 870–874). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- March J, & Simon H (1958). Organisations (1st ed.). New York, NY: Wiley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris ZS, Wooding S, & Grant J (2011). The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 510–520. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2012). Partnerships for environmental public health evaluation metrics manual. NIH Publication No.12–7825. Retrieved from http://www.niehs.nih.gov/pephmetrics

- O’Fallon LR, Wolfe GM, Brown D, Deary A, & Olden K (2003). Strategies for setting a national research agenda that is responsive to community needs. Environmental Health Perspectives, 111(16), 1855–1860. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell KG, Thompson MR, Rice JW, Senier L, Brown P, & Suuberg E (2013). Bridging research and environmental regulatory processes: The role of knowledge brokers. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(21), 11985–11992. doi: 10.1021/es4025244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettibone K (2017). Environmental health sciences translational research framework. Research Triangle Park, NC: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2016). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PA, Cooney CL, Kastner MA, Lees J, Sasisekharan R, Yaffe MB, . . . Sur M (2011). The third revolution: The convergence of the life sciences, physical sciences and engineering. Washington, DC: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Washington Office; Retrieved from http://www.convergencerevolution.net/ [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt JP (n.d.) Experience, skills and intentions of social entrepreneurs towards innovation. Retrieved from http://www.innovativedutch.com/research/publications

- Tennant MR, Butson LC, Rezeau ME, Prudence JT, Boyle ME, & Clayton G (2001). Customizing for clients: Developing a library liaison program from need to plan. Bulletin of Medical Library Association, 89(1), 8–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MR, & Schwartz Barcott D (2017). The concept of exposure in environmental health for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(6), 1315–1330. doi: 10.1111/jan.13246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall JM, Mold J, & Fagnan L (2007). Patient-based research—Blue highways on the NIH roadmap. Journal of American Medical Association, 297(4), 403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2004). World report on knowledge for better health: Strengthening health systems. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/rpc/meetings/pub1/en/

- Yost J, Dobbins M, Traynor R, DeCorby K, Workentine S, & Greco L (2014). Tools to support evidence-informed public health decision-making. BMC Public Health, 14, 728–741. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.