Abstract

We present the backbone and sidechain NMR assignments and a structural analysis of the 178-residue wild-type γS-crystallin and the cataract-related point mutant, γS-G18V. γS-crystallin is a structural component of the eye lens, which maintains its solubility and stability over many years. NMR assignments and continued structural investigations of γS-crystallin and aggregation-prone variants will advance understanding of cataract formation.

Keywords: crystallin, eye lens, cataract, protein aggregation, protein stability, solution-state NMR assignments

Biological Context

The structural proteins in the eye lens, known as crystallins, are interesting structural targets because of their very high stability and solubility. These proteins are classified into two broad families; the α-crystallins form polydisperse complexes and have a solubilizing function (Horwitz, 1992, Tanaka et al, 2008), binding to other crystallins via a pH-dependent mechanism (Jehle et al, 2010). By contrast, the βγ-crystallins play a purely structural role. Crystallins of either type can aggregate due to either genetic mutation or post-translational modification, forming a cataract. Cataract, listed as a priority eye disease by the World Health Organization, is responsible for 48% of blindness worldwide. Epidemiological studies have shown that even in progressive age-related cataract, heredity is a major factor, possibly affecting 70% of cases. This indicates that hereditary features of the crystallin proteins affect their solubility, with point mutations causing congenital cataract being merely the most dramatic examples of a widespread phenomenon. Determining the molecular mechanisms of cataract formation will require structural studies of the native protein and cataract-related variants.

γS-crystallin is the most highly expressed crystallin in the cortex of the lens during development (Wang et al, 2004). All the crystallins are highly conserved, however γS-crystallin has the most highly conserved sequence among mammalian species, for example between human and murine γS there is 89% sequence identity and 96% sequence homology. A clinically-discovered polymorphism in the γS-crystallin gene (γS-G18V) that causes congenital cortical cataract in early childhood (Sun et al, 2005) provides a useful model system for investigation of cataract formation. Subsequent investigation of the biophysical properties of γS-G18V indicated that while the point mutation causes a significant thermodynamic destabilization of the protein fold (Ma et al, 2009), the aggregation of γS-G18V appears to be due to alteration of the local intermolecular forces between γS monomers, rather than a bulk unfolding of the protein (Brubaker et al, 2011). Solution-state structures of the wild-type and variant proteins will provide insight into the extent and type of the local structural perturbations. Previous NMR studies on γS include a solution structure of the highly homologous murine protein (Wu et al, 2005), characterization of its destabilizing variant F9S (Mahler et al, 2011), and extensive backbone and sidechain assignments of wild-type human γS (γS-WT) at pH 6.0 (Baraguey et al, 2004). Although structures of γS-WT and its variants are not yet available, analysis of the assignments reveals chemical shift changes suggesting substantial structural perturbation in the region of the point mutations. Here we report the backbone and sidechain resonance assignments of γS-WT and γS-G18V at 22 °C and pH 4.5 and the differences between them.

Methods and Experiments

Sample Preparation:

Recombinant human wild-type human γS-crystallin and variant human γS containing the G18V substitution were expressed and purified as described previously (Brubaker et al, 2011). Briefly, a plasmid containing either the wild-type or G18V human γS-crystallin sequence was amplified with primers containing flanking restriction sites for NcoI and XhoI, an N-terminal 6x His tag, and a TEV protease cleavage sequence (ENLYFQG). The PCR product was cloned into the pET28a(+) vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). For expression in minimal media, an appropriate volume of overnight culture of Rosetta E. coli such that the final OD550 would be approximately 0.9 units was spun down and resuspended in 1 L of M9 minimal media with U-13C glucose and 15NH4Cl. The cells were thereafter grown at either 37 °C (γS-WT) or 25 °C (γS-G18V). The cells were allowed to grow for an additional hour before induction of protein expression. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were grown for either an additional 5–6 hours (γS-WT) or 16–24 hours (γS-G18V), and harvested by centrifugation. The His-tagged protein was then purified on a nickel column and the 6x His tag removed by cleavage with TEV protease; in both proteins the N-terminal methionine is replaced with glycine as a consequence of the TEV protease cleavage sequence. After purification, the samples were dialyzed against 10 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.5), concentrated, and supplemented with 0.05% sodium azide, 2 mM TMSP, and 10% D2O. The final sample concentrations used in experiments were 2.11 mM and 1.50 mM for γS-WT and γS-G18V, respectively.

NMR Experiments:

Experiments were performed at 22 °C on a Varian UnityINOVA system operating at 800 MHz equipped with a 1H/13C/15N 5mm tri-axis PFG triple-resonance probe. Resonance assignments were made using the following experiments: 2D 1H-15N HSQC, 2D 1H-13C HSQC, 3D HNCACB, 3D HNCO, 3D CBCA-(CO)NH, 3D H(C)CH-COSY, 3D H(C)CH-TOCSY, 3D 1H-1H-13C NOESY-HSQC (140 ms mixing), 3D 1H-1H-15N NOESY-HSQC (150 ms mixing). Aromatic side-chain resonances were assigned using aromatic 2D 1H-13C HSQC and 3D1H-1H-13C NOESY-HSQC (140 ms mixing) spectra. Decoupling of 13C and 15N nuclei were performed by WURST (Kupce and Freeman, 1995), and GARP (Shaka et al, 1985), sequences, respectively. 1H shifts were referenced to TMSP, and 13C and 15N were referenced indirectly to TMSP. NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al, 1995), and analyzed using Sparky (Goddard and Kneller, 2011).

Assignments and Data Deposition

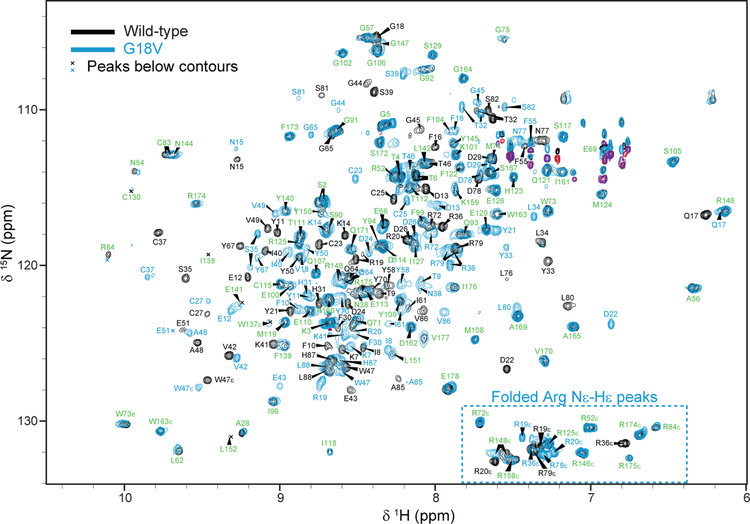

In general the data for both γS-WT and γS-G18V were of good quality, with γS-WT having higher sensitivity than γS-G18V at comparable concentrations. Because γSG18V is sensitive to thermal stress, NMR experiments were performed at 22 °C. At this temperature, improved sensitivity was observed at pH 4.5. Signal from residues between L151 and R158 were weak or undetectable in both datasets, and in general backbone amides from the N-terminal domain were much stronger and more complete than those from the C-terminal domain, as is indicated by the relative peak intensities in the 1H-15N HSQC (Figure 1). Final assignments for both γS-WT and γS-G18V (all numbers given respectively) included 90.5% (153) and 87.6% (148) of the 169 expected backbone amides (excluding prolines and G1). 96.1% (171) and 94.4% (168) of 178 sidechains had complete aliphatic resonance assignments. Aromatic sidechain assignments included all histidines, all tryptophans, all phenylala-nines except F10 in γS-G18V, and 8 of 14 tyrosines in both variants. All sidechain primary amides were assigned except for N38 in γS-G18V. The assignments for γSWT are mostly consistent with the existing assignments deposited in the BioMagRes-Bank for pH 6.0 (Baraguey et al, 2004).

Fig. 1.

2-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC of γS-WT (black) and γS-G18V (blue) showing assignments. Peaks that do not shift between γS-WT and γS-G18V are labeled in green. Arginine Nε-Hε cross-peaks are folded in the 15N dimension and appear in the lower-right portion of the spectrum. Experimental parameters: 1H: center frequency (CF) 4.8 ppm, spectral width (SW) 10.0 kHz; 15N: CF 118.7 ppm, SW 3.8 kHz.

Assignment Strategies:

The high degree of structural symmetry between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of γS-crystallin allowed easily backbone assignment of residues that shared homologous positions on the two domains. In addition to this interdomain symmetry, each double Greek key domain has conserved residues at certain positions, and can be divided into symmetric subdomains (Figure 2b). This intradomain symmetry allows the rapid assignment of residues with “partners” at other positions in the structure in the absence of obvious inter-residue connectivity, but also has a tendency to crowd these regions of the spectra. In particular, the sidechain resonances of N15, N54, D103, and N144 occur at these positions and show significant peak overlap in several experiments.

Fig. 2.

a) Comparison of γS-WT and γS-G18V Cα and Cβ chemical shifts by residue number. b) Alignment of γS-WT subdomains, with homologous residues highlighted in blue (first subdomains) and red (second subdomains). Residues which are homologous across all four subdomains are highlighted in purple.

Chemical Shift Variation:

The G18V substitution appears to cause widespread disruption throughout the N-terminal domain of γS-crystallin rather than only the residues immediately around it. However, the protein remains folded as indicated by chemical shift dispersion and other biophysical data (Brubaker et al, 2011). In general, chemical shift variation between γS-WT and γS-G18V occurs largely between residues 1 and 83, which show significant shifts in backbone and sidechain chemical shift frequencies (Figure 1, Figure 2a), while the C-terminal domain shows little difference in either the amide or aliphatic chemical shift frequencies between the two variants. Furthermore, the largest variation in chemical shifts appears to be primarily in the first subdomain of the N-terminal domain of γS-G18V (residues 1–39).

Multiple Conformers:

In the process of assigning γS-G18V it became apparent that some residues in the N-terminal domain around V18 seemed to be populating two discrete conformations with different backbone chemical shifts (Figure 3). In particular residues S2, G5, R19, T32–C37, I61, Q64, R72, H87 and L88 appear appear to exist in two conformations according to the NMR data (Figure 1), while residues T32–C37 appear to have the strongest signal, with the secondary chemical shifts easily identifiable in backbone through-bond experiments (Figure 4). These residues correspond with the region predicted by molecular dynamics simulations to shift, allowing water into the interior of the N-terminal domain as a result of the local destabilization caused by the G18V substitution (Brubaker et al, 2011). It is interesting to note that the weaker secondary backbone amide resonances often are closer or even identical to the chemical shifts for γS-WT, suggesting that γS-G18V may be able to access both the wild-type conformation and an alternate conformation that may be related to cataract formation.

Fig. 3.

Model of γS-G18V from molecular dynamics simulation (Brubaker et al, 2011) with residues showing evidence of multiple conformations in γS-G18V in NMR spectra highlighted. Residues are colored by type: positive (blue), polar (green), negative (red), other (yellow), and V18 (orange).

Fig. 4.

Backbone walk of γS-G18V showing slices of HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH experiments corresponding to residues displaying evidence of two conformations. Experimental parameters: 1H: center frequency (CF) 4.8 ppm, spectral width (SW) 13.0 kHz; 13C: CF 46.0 ppm, SW 16.1 kHz; 15N: CF 118.7 ppm, SW 3.0 kHz.

Data Deposition:

The assigned chemical shifts for γS-WT and γS-G18V have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under accession numbers 17576 and 17582, respectively.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Melanie Cocco and AJ Shaka for helpful discussions and Evgeny Fadeev for excellent NMR facility management. This work was supported by NSF-CAREER CHE-0847375 and NIH RO1GM-78528.

Contributor Information

William D. Brubaker, University of California, Irvine, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry

Rachel W. Martin, University of California, Irvine, Departments of Chemistry and Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, 4136 Natural Sciences 1, Irvine, CA 92697-2025, Tel.: (949) 824-7959, rwmartin@uci.edu

References

- Baraguey C, Skouri-Panet F, Bontems F, Tardieu A, Chassaing G, Lequin O (2004) 1H, 15N and 13C resonance assignment of human gammaS-crystallin, a 21 kDa eye-lens protein. Journal of Biomolecular NMR 30:385–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker WD, Freites JA, Golchert KJ, Shapiro RA, Morikis V, Tobias DJ, Martin RW (2011) Separating instability from aggregation propensity in gammaS-crystallin variants. Biophysical Journal 100(2):498–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister G, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. Journal of Biomolecular NMR 6:277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG (2011) SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz J (1992) Alpha-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89(21):10,449–10,453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehle S, Rajagopal P, Bardiaux B, Markovic S, Kühne R, Stout JR, Higman VA, Klevit RE, van Rossum BJ, Oschkinat H (2010) Solid-state NMR and SAXS studies provide a structural basis for the activation of alpha B-crystallin oligomers. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 17:1037–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupce E, Freeman R (1995) Adiabatic pulses for wide-band inversion and broadband decoupling. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series A 115(273–276) [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Piszczek G, Wingfield P, Sergeev Y, Hejtmancik J (2009) The G18V CRYGS mutation associated with human cataracts increases gammaS-crystallin sensitivity to thermal and chemical stress. Biochemistry 48:7334–7341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler B, Doddapaneni K, Kleckner I, Yuan C, Wistow G, Wu Z (2011) Characterization of a transient unfolding intermediate in a core mutant of s-crystallin. Journal of Molecular Biology 405:840–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaka A, Barker PB, Freeman R (1985) Computer-optimized decoupling scheme for wideband applications and low-level operation. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 64:547–552 [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Ma Z, Li Y, Liu B, Li Z, Ding X, Gao Y, Ma W, Tang X, Li X, Shen Y (2005) Gamma-S crystallin gene (CRYGS) mutation causes dominant progressive cortical cataract in humans. Journal of Medical Genetics 42(9):706–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Tanaka R, Tokuhara M, Kunugi S, Lee Y, Hamada D (2008) Amyloid fibril formation and chaperone-like activity of peptides from alpha-crystallin. Biochemistry 47(9):2961–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Garcia CM, Shui YB, Beebe DC (2004) Expression and regulation of alpha-, beta-, and gamma-crystallins in mammalian lens epithelial cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 45:3608–3619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Delaglio F, Wyatt K, Wistow G, Bax A (2005) Solution structure of (gamma)S crystallin by molecular fragment replacement NMR. Protein Science 14(12):2142–2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]