Abstract

Many brain disorders exhibit altered synapse formation in development or synapse loss with age. To understand the complexities of human synapse development and degeneration, scientists now engineer neurons and brain organoids from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSC). These hIPSC-derived brain models develop both excitatory and inhibitory synapses and functional synaptic activity. In this review, we address the ability of hIPSC-derived brain models to recapitulate synapse development and insights gained into the molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic alterations in neuronal disorders. We also discuss the potential for more accurate human brain models to advance our understanding of synapse development, degeneration, and therapeutic responses.

INTRODUCTION

In less than a decade, human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSCs) have revolutionized research into complex human disorders (Dolmetsch and Geschwind, 2011), from neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia (Brennand et al., 2011; Windrem et al., 2017), autism (Marchetto et al., 2010, 2017; Krey et al., 2013; Mariani et al., 2015; Nestor et al., 2016), and microcephaly (Lancaster et al., 2013; Qian et al., 2016) to neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s (Israel et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2018), Parkinson’s (Miller et al., 2013; Vera et al., 2016; Prots et al., 2018), and Huntington’s (HD iPSC Consortium, 2012; Xu et al., 2017) diseases (Table 1). These disorders exhibit altered synapse density and/or morphology as demonstrated by both animal models and postmortem patient samples (Penzes et al., 2011) and are collectively referred to as synaptopathies (Brose et al., 2010). However, the mechanisms that underlie synaptic alterations in the human brain are unclear.

TABLE 1:

Synapses in hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids.a

| Author (year) | Disease | Culture time | Brain region | Synapse markers | Protocol | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. (2018) | Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Up to 6 mo | Cerebrum |

|

|

|

| Prots et al. (2018) | Parkinson’s disease | 20 d of neuronal differentiation | Cortical neurons |

|

hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

| Marchetto et al. (2017) | Idiopathic autism | Up to 50 d | Cortical neurons |

|

hIPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPC) and neurons (2D) |

|

| Quadrato et al. (2017) | None | Up to 13 mo | Whole brain |

|

Organoid(matrigel) |

|

| Windrem et al. (2017) | Schizophrenia | Up to 200 d | Glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes) |

|

hIPSC-derived glia and mouse brain chimera |

|

| Xu et al. (2017) | Huntington’s disease (HD) | 34, 48, and 50 d | Forebrain |

|

hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

| Odawara et al. (2016) | None | Up to 46 wk | Cortical neurons |

|

hIPSC-derived neurons cultured on MEA plates |

|

| Qian et al. (2016) | Zika virus-induced microcephaly | Up to 84 d |

|

|

Organoid(spinning bioreactors) |

|

| Mariani et al. (2015) |

|

Up to 6 wk | Telencephalic (cerebrum) |

|

Organoid(free-floating) |

|

| Pas¸ca et al. (2015) | None | Up to 9 mo | Cerebrum |

|

Forebrain organoid(free floating) |

|

| Krey et al. (2013) | Timothy syndrome | Up to 5 wk | Cortical neurons | SYN1 | hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

| Israel et al. (2012) | Sporadic and familial AD | 3 wk | Neurons | SYN1 | hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

| Shi et al. (2012) | None | Up to 100 d | Cortical neurons |

|

hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

| Brennand et al. (2011) | Schizophrenia | Up to 6 wk | Cortical neurons |

|

hIPSC-derived neurons (2D) |

|

aThis is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all hIPSC studies that examined synapses.

bUsed primarily as a cell type marker rather than a synaptic marker.

hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids recapitulate human brain development in the laboratory, providing a unique opportunity to uncover the dynamic molecular events leading to altered synapse formation in neurodevelopmental disorders or synapse loss in neurodegeneration. In this review, we discuss how both hIPSC-derived two-dimensional (2D) neurons and three-dimensional (3D) brain organoids develop synapses and synaptic activity that can be used to model complex neuronal disorders.1 Each of these models has particular strengths and challenges for simulating human synapse development and degeneration. In general, brain organoids exhibit more complexity, whereas hIPSC-derived neurons provide more uniform cultures of specific cell types (Kelava and Lancaster, 2016).

Brain organoids recapitulate many aspects of physiological human brain development. Temporally, brain organoids closely mimic human fetal brain development, as revealed by transcriptional analysis and synaptic development, thus necessitating lengthy culture times for functional synapse maturation (Lancaster et al., 2013; Mariani et al., 2015; Pas¸ca et al., 2015; Kelava and Lancaster, 2016). During prenatal development, excitatory synapses form along the dendrite shaft or on filopodia-like projections, but shift to specialized dendritic spines postnatally (Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2004; Koleske, 2013). Mature dendritic spines consist of a polarized spine neck and head with an electron-dense postsynaptic density (PSD) adjacent to a presynaptic axon terminal (Lynch et al., 2007). These axospinous synapses have been documented only in brain organoids (Quadrato et al., 2017), although similar investigations are needed to determine whether hIPSC-derived neurons exhibit morphological changes associated with excitatory synapse formation (Marchetto et al., 2010). Observing the morphological changes associated with synapse maturation suggests that organoids closely mimic human brain development.

In addition to modeling the time course of human brain development, brain organoids self-organize into structures that recapitulate human brain organization. They develop ventricles with surrounding progenitor zones that contain radial glia, and they form deep and superficial cortical layers (Lancaster et al., 2013; Pas¸ca et al., 2015). Brain organoids also contain astrocytes (Lancaster et al., 2013; Pas¸ca et al., 2015; Dezonne et al., 2017; Quadrato et al., 2017; Sloan et al., 2017). Astrocytes critically support synapse development, maintenance, and function, and are thus important to consider when modeling synaptic disorders (Allen and Eroglu, 2017). In certain cases, myelinating oligodendrocytes have also been described in brain organoids (Di Lullo and Kriegstein, 2017; Madhavan et al., 2018), although most myelination occurs postnatally (Miller et al., 2012). Organoids also recapitulate biophysical properties of human brain development, allowing for events such as cortical folding (Li et al., 2017; Karzbrun et al., 2018). The 3D matrix of organoids may also retain secreted factors that regulate synaptic development and degeneration, as suggested by the use of hydrogels to capture amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s human neural cell culture (Choi et al., 2014, 2016). Thus, brain organoids capture the cellular diversity, temporal dynamics, and structural organization of the human brain.

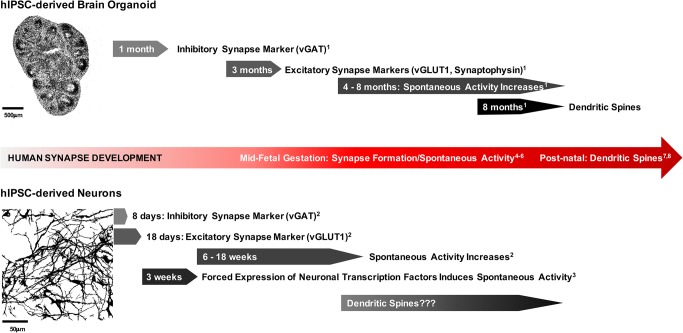

However, depending on the protocol, organoids contain diverse ratios of particular cell types. For example, whole-brain organoids contain hindbrain, midbrain, forebrain, and even retinal cells (Kelava and Lancaster, 2016; Quadrato et al., 2017), whereas hIPSC-derived neurons can be directed toward specific lineages and/or enriched by fluorescence-analyzed cell sorting. Addition of astrocytes to neuronal cultures promotes synapse maturation and spontaneous action potential formation. This can be accomplished through 1) cultures that generate both neurons and astrocytes through a shared progenitor, 2) hIPSC-derived neuron-astrocyte cocultures, or 3) application of astrocyte-conditioned media to hIPSC-derived neurons (Tang et al., 2013; Odawara et al., 2016; Gunhanlar et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2018). Defined cocultures can also be used to address how specific cell types contribute to disease progression. For example, Down syndrome hIPSC-derived astrocytes compromise synaptogenesis of unaffected hIPSC-derived neurons (Araujo et al., 2018). Furthermore, forced expression of neuronal transcription factors, either neurogenin-2 or neuroD1, can rapidly induce neuronal maturation and functional synaptic activity within 3 wk of hIPSC-derived neuron culture (Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, while organoids enable the study of synapses in a complex environment that mimics human fetal brain development, hIPSC-derived neurons allow for the enrichment of specific brain cell types and rapid induction of physiological maturation (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1:

Time course of synapse development across hIPSC models. Brain organoids develop synapses and synaptic activity similar to those of the human brain. During midfetal gestation (∼18 wk), synapses form and spontaneous activity begins (4–6: Tau and Peterson, 2010; Moore et al., 2011; Luhmann et al., 2016). Dendritic spines form postnatally (7,8: Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2004; Koleske, 2013). In both whole-brain organoids (1: Quadrato et al., 2017) and forebrain cortical spheroids (Pas¸ca et al., 2015), spontaneous activity begins after ∼4 mo of culture. Furthermore, whole-brain organoids exhibit dendritic spines after 8 mo of culture (1: Quadrato et al., 2017). By contrast, hIPSC-derived neurons exhibit earlier expression of synaptic markers and spontaneous activity (2: Nadadhur et al., 2017) that can be increased by forced expression of neuronal transcription factors (3: Zhang et al., 2013). It is unclear whether hIPSC-derived neurons form dendritic spines. The top image is a cryosection of a forebrain cortical spheroid developed according to the methods of Pas¸ca et al. (2015), and the bottom image is a 2D hIPSC-derived cortical neuron culture developed according to Brennand et al. (2015).

In this review, we address the ability of both hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids to recreate altered synapse development and degeneration in the lab,2 which will ultimately enable therapeutic screens for restored synaptic connections. We also discuss opportunities for improved hIPSC models that more accurately reflect human synaptopathies.

SYNAPSE DEVELOPMENT

Before hIPSC-derived models were available, research on human synapses was limited to a static snapshot of brain development available from postmortem tissue. Postmortem studies predominantly focused on excitatory synapses at dendritic spines, which are evident by Golgi staining (Mancuso et al., 2013). Dendritic spines are the primary sites of excitatory stimulation leading to long-term potentiation and learning and memory formation (Lynch et al., 2007). In an immature state, excitatory synapses form between the presynaptic axon and the dendritic shaft or filopodia-like spine precursors (Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2004). Spines then mature into a polarized mushroom-shaped structure with a distinct head and neck (Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2004). Glutamate receptors cluster at the tip of the spine head in the electron-dense PSD (Lynch et al., 2007). In the human prefrontal cortex, excitatory synaptogenesis begins around 18 wk of fetal gestation and coincides with spontaneous action potential formation (Tau and Peterson, 2010; Moore et al., 2011). Early synaptogenesis occurs primarily along the dendritic shaft, but shifts to dendritic spines in later peri- and postnatal development (Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2004; Petanjek et al., 2011). Excitatory synapses are then either strengthened or pruned in an activity-dependent manner throughout childhood, leading to relatively stable synapses in adulthood (Penzes et al., 2011). Conversely, inhibitory synapses suppress action potential formation and refine the amount of excitatory synapses (Craig and Kang, 2007). Inhibitory synapses form almost exclusively along the dendritic shaft and lack the electron-dense PSD and are thus not evident by Golgi staining or electron microscopy without the use of immunogold labeling. Despite difficulties visualizing inhibitory synapses in postmortem tissue, it is known that they critically regulate brain development and cognitive function. Disruptions in the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory synapses contribute to both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders (Penzes et al., 2011; Gao and Penzes, 2015).

ALTERED SYNAPSE FORMATION IN NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

Golgi staining of autism postmortem brain tissue reveals increased dendritic spines on cortical pyramidal neurons (Hutsler and Zhang, 2010; Tang et al., 2014). The observed increase in dendritic spines, the primary sites of excitatory neurotransmission, suggests increased excitatory-to-inhibitory signaling in autism (Takarae and Sweeney, 2017). This hyperexcitability could account for the increased risk of epilepsy in the autism population (Tuchman and Rapin, 2002). However, electroencephalographic data from living patients suggest a more complex picture than global hyperexcitability, as autism patient brains exhibit local areas of hyperexcitability balanced by underconnectivity at longer distances (Boutros et al., 2015). It is also unclear whether the increased number of synapses in autism are functional and stabilized into mature synaptic connections or exist as silent synapses without activity. Silent synapses may be subject to greater loss, leading to neurodegeneration and regression in autism (Hanse et al., 2013; Kern et al., 2013). It is critical that human brain models capture the lifetime of synapse formation, refinement, maintenance, and loss to accurately reflect disease progression.

Unlike in autism, schizophrenia postmortem brains exhibit decreased dendritic spines in both the cortex and hippocampus (Glantz and Lewis, 2000; Law et al., 2004; Kolomeets et al., 2005; Lewis and Sweet, 2009; Sweet et al., 2009). However, decreased GABAergic inhibitory signaling in schizophrenia may lead to a hyperexcitable state, similar to autism (Gao and Penzes, 2015). This further highlights the need for human brain models that capture the altered development of both excitatory and inhibitory synapses to unravel the complexities of neurodevelopmental disorders.

STEM CELL MODELS OF SYNAPSE DEVELOPMENT

hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids demonstrate a remarkable ability to mirror human fetal synapse development and provide insights into neurodevelopmental pathologies. In both models, excitatory synapse formation and spontaneous action potentials increase with age similar to the time course of prenatal brain development (Shi et al., 2012; Odawara et al., 2016; Quadrato et al., 2017) (Figure 1). By 8 mo in culture, brain organoids exhibit excitatory synapses on dendritic spines; reconstruction of serial-section electron microscopy reveals that 30 out of 37 synapses formed on dendritic spines (Quadrato et al., 2017). By contrast, after 300 d of hIPSC-derived neuron coculture with astrocytes, excitatory synapses still primarily form along dendrites and soma (Odawara et al., 2016). Notably, the number of synaptophysin-positive excitatory synapses more than doubled between 112 and 300 d of neuron–astrocyte coculture (Odawara et al., 2016). In both hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids, spontaneous action potentials (spikes) increased with culture time. Spontaneous action potentials begin early in development in the absence of a stimulus and play important roles in establishing neural circuits (Luhmann et al., 2016). At 8 mo, brain organoid spike frequency varied from 0 to 6 Hz (mean = 0.66 Hz) (Quadrato et al., 2017). By contrast, hIPSC-derived neurons cocultured with astrocytes averaged a spike frequency of ∼2 Hz at 6 wk, which increased to ∼5 Hz between 12 and 18 wk and remained constant through 34 wk of culture (Odawara et al., 2016). Forced expression of neuronal transcription factors, either neurogenin-2 or NeuroD1, can be used to accelerate synapse function, resulting in spontaneous action potentials after 3 wk of culture (Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, hIPSC-derived neurons acquire functional synapses earlier than brain organoids, and this activity can be accelerated through forced expression of neuronal-specific genes.

hIPSC-derived neurons and brain organoids form specialized excitatory and inhibitory synapses. In brain organoids, excitatory synapse markers, such as synaptophysin-1 (syn-1) and vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (vGLUT-1), express after 3 mo of culture, while the inhibitory presynaptic marker, vesicular GABA Transporter (vGAT), expresses at 1 mo of culture (Quadrato et al., 2017). Similarly, in hIPSC-derived neurons, vGAT expression increases at 8 d of culture, preceding increased vGLUT-1 expression after 18 d (Nadadhur et al., 2017). vGAT expression before glutamatergic synapse expression likely reflects the early developmental phenomenon of GABA-induced excitation. GABA-induced excitation mediates neuronal migration and the formation of neuronal connections, while preventing glutamate cytotoxicity in early development (Ben-Ari and Tyzio, 2009; Bortone and Polleux, 2009). Later in prenatal development, GABA switches from excitation to inhibition through expression of the potassium chloride transporter KCC2, thus establishing an excitatory-to-inhibitory balance (Bortone and Polleux, 2009; Ben-Ari, 2014; Sivakumaran et al., 2015; Leonzino et al., 2016). Forebrain organoids exhibit GABA-induced excitation and show increased KCC2 expression with longer development (84 wk) (Qian et al., 2016). By contrast, GABA-induced excitation decreases after 2 wk of hIPSC-derived neuron culture (Rushton et al., 2013), providing further support that brain organoids develop similarly to the brain in utero, while hIPSC-derived neurons exhibit accelerated synapse formation and function.

STEM CELL MODELS OF SYNAPTIC ALTERATIONS IN NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

In addition to recapitulating normal synapse formation and function, hIPSC brain models provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic abnormalities in neurodevelopmental disorders. Both schizophrenia and autism exhibit synaptic abnormalities in the cerebral cortex (Hutsler and Zhang, 2010; Selemon and Zecevic, 2015; Ajram et al., 2017). hIPSC-derived neurons from schizophrenia patients exhibit reduced neuronal connections and decreased RNA expression of excitatory synapse markers, including PSD-95 and glutamate receptors, which are rescued by the antipsychotic drug Loxapine (Brennand et al., 2011). In a study of autism patients with larger than average head size, hIPSC-derived neurons exhibit decreased excitatory synapses and action potentials and increased inhibitory synapse markers (Marchetto et al., 2017). Similarly, macrocephaly-associated autism forebrain organoids form more inhibitory neurons and synapses (Mariani et al., 2015). These results challenge the simplified notion of hyperexcitability in autism, particularly for macrocephaly-associated patients. Similarly, hIPSC-derived neurons from autism patients with Rett syndrome exhibit decreased excitatory synapses (Marchetto et al., 2010) but increased GABA-induced excitation, which is rescued by KCC2 expression (Tang et al., 2016). These results demonstrate how hIPSC-derived neurons can reveal patient-specific differences in genetically diverse spectrum disorders.

In addition to modeling genetic causes of altered synapse development, hIPSC-derived neuronal models can be used to examine the impact of environmental factors on neurodevelopment. For example, the hormone oxytocin promotes KCC2 expression and the shift from GABA-induced excitation to inhibition (Leonzino et al., 2016). Autism impairs the oxytocin-mediated GABA shift (Ben-Ari, 2014). Thus, hIPSC brain organoids have the potential to model hormone action at the level of synapses and synaptic function. This particular feature will be important for addressing how environmental factors that disrupt hormonal balances contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders (Moosa et al., 2018), as well as the potential benefits of hormone therapies (DeMayo et al., 2017).

FUTURE ADVANCES IN STEM CELL MODELS OF SYNAPSE DEVELOPMENT

Although hIPSC-derived brain models reflect many aspects of human synapse formation and function, there are opportunities for improvement in the areas of synapse development and the modeling of neurodevelopmental disorders. One major limitation is the heterogeneity of cell types in brain organoids. In matrigel-embedded whole-brain organoids, only 30% of organoids express forebrain markers (Quadrato et al., 2017). Because autism and schizophrenia primarily affect forebrain regions, whole-brain organoids may not be best suited to model certain disorders. Using the matrigel-embedding protocol, it will be necessary to screen and select for specific brain regions to compare synapse development in patients and typically developing individuals. Alternatively, more recent protocols drive neuronal identity toward specific brain regions, such as forebrain cortical spheroids (Pas¸ca et al., 2015) or brain region–specific organoids cultured in miniature bioreactors (Qian et al., 2016, 2018). Furthermore, while brain organoids exhibit spontaneous network activity, the ability to recreate activity-dependent postnatal synaptic refinement is needed to address how synapse strengthening and/or pruning is altered in neurodevelopmental disorders (Penzes et al., 2011). Recent research demonstrates that the activity of photoreceptor cells in brain organoids can be modulated with light after 7–9 mo in culture, demonstrating the potential to study activity-dependent synaptic refinement (Quadrato et al., 2017). Additionally, optogenetics can be used to control local and global networks of synaptic activity in hIPSC-derived neuronal models (Klapper et al., 2017). Finally, the recent engraftment of human brain organoids into mouse brains (Mansour et al., 2018) provides a model to assess how neurodevelopmental disorders affect synapse formation and refinement in vivo. hIPSC–animal chimeras may also be used to address how altered synapse formation affects behavior, similar to research in which schizophrenia hIPSC-derived glial cells engrafted into the mouse brain resulted in schizophrenia-like behaviors (Windrem et al., 2017).

STEM CELL MODELS OF NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASE

While hIPSC-derived neuronal models reflect neurodevelopmental pathology, their developmental stages, which are similar to those of the human fetal brain, present a challenge for modeling synapse loss in neurodegenerative disorders. hIPSC research shows promise for overcoming this challenge and providing insights into the mechanisms of synapse loss in neurodegenerative disorders. Synapse loss precedes neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases (Wishart et al., 2006; Koffie et al., 2011; Bellucci et al., 2016). Researchers need experimental models to observe and manipulate the dynamic molecular events underlying synapse loss, especially because animal neurodegenerative models can lack key pathological features. For example, mouse models of familial Alzheimer’s disease lack tau neurofibrillary tangles (Choi et al., 2014). Thus, brain models are needed to capture human-specific neurodegenerative pathology. These models will allow us to address how synapse loss contributes to neurodegeneration and to develop therapies for synapse recovery.

In Alzheimer’s disease, neurofibrillary tangles first emerge in the cortex and then spread to the hippocampus (Serrano-Pozo et al., 2011). hIPSC-derived cortical neurons from patients with familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease exhibit increased amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition and phosphorylated tau; however, no differences in the density of synapsin-1–positive synapses was observed, and cell death was not examined (Israel et al., 2012). In a recent study of hIPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia-like cells containing the Alzheimer’s disease–associated APOE4 variant, neurons exhibited increased excitatory synapses, while astrocytes and microglia showed impaired Aβ clearance (Lin et al., 2018). Alzheimer’s disease hIPSC-derived neurons may require enhanced aging techniques or insults that trigger neuronal cell death in order to study synapse loss in neurodegeneration. For example, growth factor withdrawal increases cell death in a Huntington’s disease hIPSC model of cortical neurodegeneration (Estrada-Sánchez and Rebec, 2013); however, the effect on synapses was not examined (Xu et al., 2017). In another example of insult promoting neurodegenerative pathology, α-synuclein oligomers impair axonal transport leading to synaptic degeneration in Parkinson’s disease hIPSC-derived cortical neurons (Prots et al., 2018). While the cortex is affected in Parkinson’s disease, the midbrain, particularly the substantia nigra, is the primary site of neurodegeneration (Maiti et al., 2017). Telomerase inhibition or progerin-mediated aging of Parkinson’s disease hIPSC-derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons induces DNA damage, mitochondrial oxidative stress, and dendrite degeneration, similar to early stages of Parkinson’s disease (Miller et al., 2013; Vera et al., 2016). The use of telomerase inhibition or progerin to promote aging-related telomere shortening suggests that aging techniques and genetic susceptibility are both necessary for using hIPSCs to model neurogenerative disorders.

ADVANCES IN STEM CELL MODELS OF SYNAPSE DEGENERATION

To fully illuminate the mechanisms of synapse loss in neurodegeneration, hIPSC models need to incorporate microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells. Microglia mediate synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease (Hansen et al., 2017). Because microglia derive from mesodermal lineages, rather than neuroectodermal lineages, they have been largely overlooked in hIPSC-derived neuronal models (Chan et al., 2007). However, recent protocols provide instructions for developing microglia-like cells from hIPSCs (Abud et al., 2017; Pandya et al., 2017), allowing researchers to interrogate how microglia shape human synapse formation and loss. Chimeras of patient and unaffected control microglia and neurons will help to determine the specific contribution of microglia to disease pathology.

Furthermore, transdifferentiation of patient fibroblasts into neurons, rather than reprogramming through a stem cell intermediate, allows for the preservation of age-related epigenetic profiles and shortened telomeres that may more accurately capture neurodegenerative pathology (Victor et al., 2018). Transdifferentiated medium spiny neurons from adult Huntington’s disease patients exhibit huntingtin (HTT) aggregates, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurodegeneration (Victor et al., 2018). While transdifferentiated neurons can be engineered into specific neuronal populations, this limited fate currently prevents brain organoid generation from transdifferentiation protocols.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Through the use of hIPSC brain models, we can begin to address the fundamental molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying human neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration. Recent advances in hIPSC-derived brain organoids, such as cell-type and brain region–specific protocols, optogenetics, aging protocols, and hIPSC–mouse chimeric models will provide even greater insights into the mechanisms of synapse formation and loss. As hIPSC-derived neurons continue to better model brain disorders, they will be powerful tools for drug development and assessment of patient-specific responses to drug therapies.

Abbreviations used:

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- hIPSC

human-induced pluripotent stem cells

- PSD

postsynaptic density.

Footnotes

1Throughout the review, hIPSC-derived neurons refer to cultures directed toward neuronal differentiation. Most hIPSC-derived neurons are 2D cultures, although some are embedded in hydrogels. Brain organoids are also derived from human IPSCs, but contain diverse neuroectodermal cells that self-assemble into 3D structures.

2Unless otherwise noted, the following sections focus on hIPSC-derived 3D whole-brain organoids and 2D forebrain cortical neurons (Muratore et al., 2014; Brennand et al., 2015; Griesi-Oliveira et al., 2015; Kelava and Lancaster, 2016).

REFERENCES

- Abud EM, Ramirez RN, Martinez ES, Healy LM, Nguyen CHH, Newman SA, Yeromin AV, Scarfone VM, Marsh SE, Fimbres C, et al. (2017). iPSC-derived human microglia-like cells to study neurological diseases. Neuron , 278–293.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajram LA, Horder J, Mendez MA, Galanopoulos A, Brennan LP, Wichers RH, Robertson DM, Murphy CM, Zinkstok J, Ivin G, et al. (2017). Shifting brain inhibitory balance and connectivity of the prefrontal cortex of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry , e1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Eroglu C. (2017). Cell biology of astrocyte-synapse interactions. Neuron , 697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo BHS, Kaid C, De Souza JS, Gomes da Silva S, Goulart E, Caires LCJ, Musso CM, Torres LB, Ferrasa A, Herai R, et al. (2018). Down syndrome iPSC-derived astrocytes impair neuronal synaptogenesis and the mTOR pathway in vitro. Mol Neurobiol , 5962–5975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Mercuri NB, Venneri A, Faustini G, Longhena F, Pizzi M, Missale C, Spano P. (2016). Review: Parkinson’s disease: from synaptic loss to connectome dysfunction. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol , 77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2014). The GABA excitatory/inhibitory developmental sequence: a personal journey. Neuroscience , 187–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Tyzio R. (2009). GABA | GABA excites immature neurons: implications for the epilepsies. In: Encyclopedia of Basic Epilepsy Research, ed. Schwartzkroin PA, Elsevier, 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bortone D, Polleux F. (2009). KCC2 expression promotes the termination of cortical interneuron migration in a voltage-sensitive calcium-dependent manner. Neuron , 53–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros NN, Lajiness-O’Neill R, Zillgitt A, Richard AE, Bowyer SM. (2015). EEG changes associated with autistic spectrum disorders. Neuropsychiatr Electrophysiol , 3. [Google Scholar]

- Brennand K, Savas JN, Kim Y, Tran N, Simone A, Hashimoto-Torii K, Beaumont KG, Kim HJ, Topol A, Ladran I, et al. , et al. (2015). Phenotypic differences in hiPSC NPCs derived from patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry , 361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J, Gelboin-Burkhart C, Tran N, Sangar S, Li Y, Mu Y, Chen G, Yu D, et al. , et al. (2011). Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature , 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, O’Connor V, Skehel P. (2010). Synaptopathy: dysfunction of synaptic function? Biochem Soc Trans , 443–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Kohsaka S, Rezaie P. (2007). The origin and cell lineage of microglia—new concepts. Brain Res Rev , 344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Kim YH, Hebisch M, Sliwinski C, Lee S, D’Avanzo C, Chen H, Hooli B, Asselin C, Muffat J, et al. , et al. (2014). A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature , 274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Kim YH, Quinti L, Tanzi RE, Kim DY. (2016). 3D culture models of Alzheimer’s disease: a road map to a “cure-in-a-dish.” Mol Neurodegener , 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AM, Kang Y. (2007). Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol , 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMayo MM, Song YJC, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. (2017). A review of the safety, efficacy and mechanisms of delivery of nasal oxytocin in children: therapeutic potential for autism and Prader-Willi syndrome, and recommendations for future research. Pediatr Drugs , 391–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezonne RS, Sartore RC, Nascimento JM, Saia-Cereda VM, Romão LF, Alves-Leon SV, de Souza JM, Martins-de-Souza D, Rehen SK, Gomes FCA. (2017). Derivation of functional human astrocytes from cerebral organoids. Sci Rep , 45091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lullo E, Kriegstein AR. (2017). The use of brain organoids to investigate neural development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci , 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch R, Geschwind DH. (2011). The human brain in a dish: the promise of iPSC-derived neurons. Cell , 831–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Sánchez AM, Rebec GV. (2013). Role of cerebral cortex in the neuropathology of Huntington’s disease. Front Neural Circuits , 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Penzes P. (2015). Common mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory imbalance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Curr Mol Med , 146–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz LA, Lewis DA. (2000). Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry , 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesi-Oliveira K, Acab A, Gupta AR, Sunaga DY, Chailangkarn T, Nicol X, Nunez Y, Walker MF, Murdoch JD, Sanders SJ, et al. (2015). Modeling non-syndromic autism and the impact of TRPC6 disruption in human neurons. Mol Psychiatry , 1350–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunhanlar N, Shpak G, van der Kroeg M, Gouty-Colomer LA, Munshi ST, Lendemeijer B, Ghazvini M, Dupont C, Hoogendijk WJG, Gribnau J, et al. (2018). A simplified protocol for differentiation of electrophysiologically mature neuronal networks from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Psychiatry , 1336–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanse E, Seth H, Riebe I. (2013). AMPA-silent synapses in brain development and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci , 839–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M. (2017). Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol , 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HD iPSC Consortium (2012). Induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Huntington’s disease show CAG-repeat-expansion-associated phenotypes. Cell Stem Cell , 264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler JJ, Zhang H. (2010). Increased dendritic spine densities on cortical projection neurons in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res , 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel MA, Yuan SH, Bardy C, Reyna SM, Mu Y, Herrera C, Hefferan MP, Van Gorp S, Nazor KL, Boscolo FS, et al. (2012). Probing sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease using induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature , 216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karzbrun E, Kshirsagar A, Cohen SR, Hanna JH, Reiner O. (2018). Human brain organoids on a chip reveal the physics of folding. Nat Phys , 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelava I, Lancaster MA. (2016). Stem cell models of human brain development. Cell Stem Cell , 736–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JK, Geier DA, Sykes LK, Geier MR. (2013). Evidence of neurodegeneration in autism spectrum disorder. Transl Neurodegener , 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapper SD, Sauter EJ, Swiersy A, Hyman MAE, Bamann C, Bamberg E, Busskamp V. (2017). On-demand optogenetic activation of human stem-cell-derived neurons. Sci Rep , 14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffie RM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. (2011). Alzheimer’s disease: synapses gone cold. Mol Neurodegener , 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleske AJ. (2013). Molecular mechanisms of dendrite stability. Nat Rev Neurosci , 536–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomeets NS, Orlovskaya DD, Rachmanova VI, Uranova NA. (2005). Ultrastructural alterations in hippocampal mossy fiber synapses in schizophrenia: a postmortem morphometric study. Synapse , 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krey JF, Pas¸ca SP, Shcheglovitov A, Yazawa M, Schwemberger R, Rasmusson R, Dolmetsch RE. (2013). Timothy syndrome is associated with activity-dependent dendritic retraction in rodent and human neurons. Nat Neurosci , 201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin C-A, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, Homfray T, Penninger JM, Jackson AP, Knoblich JA. (2013). Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature , 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law AJ, Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Harrison PJ. (2004). Reduced spinophilin but not microtubule-associated protein 2 expression in the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia and mood disorders: molecular evidence for a pathology of dendritic spines. Am J Psychiatry , 1848–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonzino M, Busnelli M, Antonucci F, Verderio C, Mazzanti M, Chini B. (2016). The timing of the excitatory-to-inhibitory GABA switch is regulated by the oxytocin receptor via KCC2. Cell Rep , 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Sweet RA. (2009). Schizophrenia from a neural circuitry perspective: advancing toward rational pharmacological therapies. J Clin Invest , 706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Muffat J, Omer A, Bosch I, Lancaster MA, Sur M, Gehrke L, Knoblich JA, Jaenisch R. (2017). Induction of expansion and folding in human cerebral organoids. Cell Stem Cell , 385–396.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y-T, Seo J, Gao F, Feldman HM, Wen H-L, Penney J, Cam HP, Gjoneska E, Raja WK, Cheng J, et al. (2018). APOE4 causes widespread molecular and cellular alterations associated with Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in human iPSC-derived brain cell types. Neuron , 1141–1154.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Sinning A, Yang J-W, Reyes-Puerta V, Stüttgen MC, Kirischuk S, Kilb W. (2016). Spontaneous neuronal activity in developing neocortical networks: from single cells to large-scale interactions. Front Neural Circuits , 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Rex CS, Gall CM. (2007). LTP consolidation: substrates, explanatory power, and functional significance. Neuropharmacology , 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan M, Nevin ZS, Shick HE, Garrison E, Clarkson-Paredes C, Karl M, Clayton BLL, Factor DC, Allan KC, Barbar L, et al. (2018). Induction of myelinating oligodendrocytes in human cortical spheroids. Nat Methods , 700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti P, Manna J, Dunbar GL. (2017). Current understanding of the molecular mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease: targets for potential treatments. Transl Neurodegener , 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso JJ, Chen Y, Li X, Xue Z, Wong STC. (2013). Methods of dendritic spine detection: from Golgi to high-resolution optical imaging. Neuroscience , 129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour AA, Gonçalves JT, Bloyd CW, Li H, Fernandes S, Quang D, Johnston S, Parylak SL, Jin X, Gage FH. (2018). An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat Biotechnol , 432–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MC, Belinson H, Tian Y, Freitas BC, Fu C, Vadodaria KC, Beltrao-Braga PC, Trujillo CA, Mendes APD, Padmanabhan K, et al. (2017). Altered proliferation and networks in neural cells derived from idiopathic autistic individuals. Mol Psychiatry , 820–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MCN, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Chen G, Gage FH, Muotri AR. (2010). A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell , 527–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani J, Coppola G, Zhang P, Abyzov A, Provini L, Tomasini L, Amenduni M, Szekely A, Palejev D, Wilson M, et al. (2015). FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell , 375–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Duka T, Stimpson CD, Schapiro SJ, Baze WB, McArthur MJ, Fobbs AJ, Sousa AMM, Sestan N, Wildman DE, et al. (2012). Prolonged myelination in human neocortical evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , 16480–16485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Ganat YM, Kishinevsky S, Bowman RL, Liu B, Tu EY, Mandal PK, Vera E, Shim J, Kriks S, et al. (2013). Human iPSC-based modeling of late-onset disease via progerin-induced aging. Cell Stem Cell , 691–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AR, Zhou W-L, Jakovcevski I, Zecevic N, Antic SD. (2011). Spontaneous electrical activity in the human fetal cortex in vitro. J Neurosci , 2391–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosa A, Shu H, Sarachana T, Hu VW. (2018). Are endocrine disrupting compounds environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder? Horm Behav , 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratore CR, Srikanth P, Callahan DG, Young-Pearse TL. (2014). Comparison and optimization of hiPSC forebrain cortical differentiation protocols. PLoS One , e105807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadadhur AG, Emperador Melero J, Meijer M, Schut D, Jacobs G, Li KW, Hjorth JJJ, Meredith RM, Toonen RF, Van Kesteren RE, et al. (2017). Multi-level characterization of balanced inhibitory-excitatory cortical neuron network derived from human pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One , e0178533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor MW, Phillips AW, Artimovich E, Nestor JE, Hussman JP, Blatt GJ. (2016). Human inducible pluripotent stem cells and autism spectrum disorder: emerging technologies. Autism Res , 513–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odawara A, Katoh H, Matsuda N, Suzuki I. (2016). Physiological maturation and drug responses of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical neuronal networks in long-term culture. Sci Rep , 26181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya H, Shen MJ, Ichikawa DM, Sedlock AB, Choi Y, Johnson KR, Kim G, Brown MA, Elkahloun AG, Maric D, et al. (2017). Differentiation of human and murine induced pluripotent stem cells to microglia-like cells. Nat Neurosci , 753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pas¸ca AM, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Tian Y, Makinson CD, Huber N, Kim CH, Park J-Y, O’Rourke NA, Nguyen KD, et al. (2015). Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods , 671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen J-E, Woolfrey KM. (2011). Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci , 285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanjek Z, Judaš M, Šimic G, Rasin MR, Uylings HBM, Rakic P, Kostovic I. (2011). Extraordinary neoteny of synaptic spines in the human prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , 13281–13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prots I, Grosch J, Brazdis R-M, Simmnacher K, Veber V, Havlicek S, Hannappel C, Krach F, Krumbiegel M, Schütz O, et al. (2018). α-Synuclein oligomers induce early axonal dysfunction in human iPSC-based models of synucleinopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci , 7813–7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H, Ming G. (2018). Generation of human brain region—specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nat Protoc , 565–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, Yao B, Hamersky GR, Jacob F, Zhong C, et al. (2016). Brain-region-specific organoids using mini-bioreactors for modeling ZIKV exposure. Cell , 1238–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrato G, Nguyen T, Macosko EZ, Sherwood JL, Min Yang S, Berger DR, Maria N, Scholvin J, Goldman M, Kinney JP, et al. (2017). Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature , 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton DJ, Mattis VB, Svendsen CN, Allen ND, Kemp PJ. (2013). Stimulation of GABA-induced Ca2+ influx enhances maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. PLoS One , e81031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemon LD, Zecevic N. (2015). Schizophrenia: a tale of two critical periods for prefrontal cortical development. Transl Psychiatry , e623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. (2011). Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med , a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Kirwan P, Livesey FJ. (2012). Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc , 1836–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumaran S, Cardarelli RA, Maguire J, Kelley MR, Silayeva L, Morrow DH, Mukherjee J, Moore YE, Mather RJ, Duggan ME, et al. (2015). Selective inhibition of KCC2 leads to hyperexcitability and epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slices and in vivo. J Neurosci , 8291–8296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan SA, Darmanis S, Huber N, Khan TA, Birey F, Caneda C, Reimer R, Quake SR, Barres BA, Pas¸ca SP. (2017). Human astrocyte maturation captured in 3D cerebral cortical spheroids derived from pluripotent stem cells. Neuron , 779–790.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RA, Henteleff RA, Zhang W, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. (2009). Reduced dendritic spine density in auditory cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology , 374–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takarae Y, Sweeney J. (2017). Neural hyperexcitability in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Sci , 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Gudsnuk K, Kuo S-H, Cotrina ML, Rosoklija G, Sosunov A, Sonders MS, Kanter E, Castagna C, Yamamoto A, et al. (2014). Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron , 1131–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Kim J, Zhou L, Wengert E, Zhang L, Wu Z, Carromeu C, Muotri AR, Marchetto MCN, Gage FH, Chen G. (2016). KCC2 rescues functional deficits in human neurons derived from patients with Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci , 751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Zhou L, Wagner AM, Marchetto MCN, Muotri AR, Gage FH, Chen G. (2013). Astroglial cells regulate the developmental timeline of human neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res , 743–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tau GZ, Peterson BS. (2010). Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology , 147–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman R, Rapin I. (2002). Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurol , 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera E, Bosco N, Studer L. (2016). Generating late-onset human iPSC-based disease models by inducing neuronal age-related phenotypes through telomerase manipulation. Cell Rep , 1184–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor MB, Richner M, Olsen HE, Lee SW, Monteys AM, Ma C, Huh CJ, Zhang B, Davidson BL, Yang XW, Yoo AS. (2018). Striatal neurons directly converted from Huntington’s disease patient fibroblasts recapitulate age-associated disease phenotypes. Nat Neurosci , 341–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windrem MS, Osipovitch M, Liu Z, Bates J, Chandler-Militello D, Zou L, Munir J, Schanz S, McCoy K, Miller RH, et al. (2017). Human iPSC glial mouse chimeras reveal glial contributions to schizophrenia. Cell Stem Cell , 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart TM, Parson SH, Gillingwater TH.(2006). Synaptic vulnerability in neurodegenerative disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol , 733–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Schutte RJ, Ng NN, Ess KC, Schwartz PH, O’Dowd DK. (2018). Reproducible and efficient generation of functionally active neurons from human hiPSCs for preclinical disease modeling. Stem Cell Res , 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Tay Y, Sim B, Yoon S-I, Huang Y, Ooi J, Utami KH, Ziaei A, Ng B, Radulescu C, et al. (2017). Reversal of phenotypic abnormalities by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene correction in huntington disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep , 619–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Bonhoeffer T. (2004). Genesis of dendritic spines: insights from ultrastructural and imaging studies. Nat Rev Neurosci , 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Pak C, Han Y, Ahlenius H, Zhang Z, Chanda S, Marro S, Patzke C, Acuna C, Covy J, et al. (2013). Rapid single-step induction of functional neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Neuron , 785–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]