Abstract

MicroRNAs regulate post-transcriptional gene expression via either translational repression or mRNA degradation. They have important roles in both viral infection and host anti-infection processes. We discovered that the miR-375 is significantly upregulated in Newcastle disease virus (NDV)-infected chicken embryonic visceral tissues using a small RNA sequencing approach. Further research revealed that the overexpression of miR-375 markedly decreases the replication of the velogenic NDV F48E9 and the lentogenic NDV La Sota by targeting the M gene of NDV in DF-1 cells. Interestingly, miR-375 has another target, ELAVL4, which regulates chicken fibrocyte cell cycle progression and decreases NDV proliferation. In addition, miR-375 can influence bystander cells by its secretion in culture medium. Our results indicated that miR-375 is an inhibitor of NDV, but can also enhance NDV growth by reducing the expression of its target ELAVL4. These results emphasize the complex roles of microRNAs in the regulation of viral infections.

Keywords: Newcastle disease virus, microRNAs, miR-375, ELAVL4, M gene

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of endogenous small non-coding RNAs of 21 to 25 nucleotides in length; they regulate the expression of target genes post-transcriptionally and have significant roles in various biological processes, including development, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis 1-3. The majority of miRNAs are transcribed as part of annotated genes from independent transcription units located in the antisense orientation or the intergenic regions of annotated genes. In animals, miRNAs are transcribed as long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) and are further cropped by the nuclear RNase III Drosha into hairpin-shaped pre-miRNAs 4, 5. These pre-miRNAs are subsequently cleaved by the cytoplasmic RNase III Dicer, after they are exported out of the nucleus by exportin-5 (Exp5), a member of the ran-dependent nuclear transport receptor family, into a ~22-nt miRNA duplex 6-8. One strand of the short-lived duplex remains as a mature miRNA, and another strand is degraded by an unknown nuclease. miRNA-induced silencing complexes (miRISCs) are formed following the loading of mature mRNA into Argonaute proteins (AGO2) 9. Then, miRISCs bind to targets by base-pairing of the miRNA seed sequence with the mRNA target sites, leading to the accelerated degradation of mRNA or the blockade of translational processing bodies 10.

miRNAs have significant roles in viral infection, either in cellular antiviral responses or the replication and propagation of viruses, via complex regulatory pathways 11-14. Several studies have shown that host miRNAs could promote or inhibit viral replication by targeting viral RNAs 15-18. For example, miR-122, a liver-specific miRNA, could promote Hepatitis C virus replication by binding to the 5′ UTR of the viral genome or by accelerating the ribosome and Ago 2 interactions with viral RNA 15, 18-20. In contrast, miR-296-5p suppresses Enterovirus 71 replication by targeting the coding regions of the viral capsid proteins VP1 and VP3 16. Many miRNAs, including MiR-342-5p, miR-485, and miR-548g-3p, are involved in antiviral processes by targeting the viral genome 17, 21, 22. In addition, viral infections can also inhibit maturation or accelerate the degradation of host microRNAs involved in the antiviral response 9, 23.

Newcastle disease (ND) is one of the most economically important infectious diseases, causing high rates of death in chickens and birds and resulting in significant economic losses to the chicken industry worldwide each year 24-27. Its causative pathogen is Newcastle disease virus (NDV), a small enveloped, linear, single negative-stranded RNA virus 28. The genome of NDV encodes six structural proteins, NP, P, M, F, HN, and L 28, 29. The HN and F proteins play important roles in viral invasion and membrane fusion, NP, P, and L constitute the RNA polymerase affecting viral replication, and the M protein is mainly involved in virion assembly and budding 29-31. Although various vaccines have been used to control NDV, it is very difficult to eliminate or effectively control NDV infection using the current vaccination strategies owing to the high frequency of viral mutation, wide range of hosts, and the antibody-dependent enhancement of NDV 26, 27. Therefore, it is imperative to study the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of NDV to develop more effective control measures.

Since miRNAs are involved in host-virus interactions, it is important to determine their roles in NDV infection. In fact, miR-485, targeting Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), plays a role in regulating NDV and Avian influenza virus H5N1 infections 17. In the current study, the expression levels of miR-375 as well as several other miRNAs were up-regulated during NDV infection based on a next-generation sequencing analysis. MiR-375, in particular, effectively suppressed NDV replication and its functions were further investigated.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

Chicken embryo fibroblast cells (DF-1), human laryngeal cancer epithelial cells (Hep2), and HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA). Ten-day-old SPF chicken embryos were obtained from Merial-vital Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China) and maintained in an incubator at 37°C.

The velogenic NDV strain F48E9 and lentogenic NDV strain rLa Sota-GFP (La Sota) were kept in our lab. Viruses were propagated in 9-day-old SPF chicken embryos, titrated by the hemagglutination assay (HA), and stored at -80°C for later use.

Virus infection and small RNA sequencing

A total of 104 PFU of each virion of F48E9 or La Sota was independently injected into the allantoic cavity of 10-day-old chicken embryos. An equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected as a negative control. The visceral tissues of each group, including heart, liver, stomach, intestines and spleen, were collected at 36 h post-infection (hpi), and three small RNA sequencing samples were sent to Novogene for sequencing (Wuhan, China). RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing analyses were performed by Novogene. Raw reads were demultiplexed and trimmed to remove low-quality sequences prior to downstream analyses. To detect differentially expressed miRNAs, a corrected p-value (q-value) of <0.01 and |log2 (foldchange)| of >1 were set as the threshold parameters for significance.

Computational target prediction

The miR-375 targets were predicted using the miRanda algorithm. The miR-375 binding sites in the ELAVL4 3′ UTR were predicted using the TargetScan website (http://www.targetscan.org/mamm_31/). Predicted targets were selected according to the optimal complementarity between miRNAs and a given mRNA based on a computational TargetScan algorithm 32. NDV genomes were predicted using BLAST.

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

The miR-375 expression plasmid p-miR-375 (miR-375), the miR-375 inhibitor plasmid p-sponge-375 (sponge-375), scramble control plasmid with mutation in binding site of miR-375 and negative control (miR-NC and sponge-NC) were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The plasmids pluc-MF (FM) and pluc-ML (LM) were derived from the psiCHECK2 vector with an inserted M gene from NDV strain F48E9 and La Sota, respectively. The full length of M gene of F48E9 and La Sota were respectively cloned into the pcDNA3.0 and pCAGGS vectors, and named as pcDNA3.0-F48E9 M (pcDNA3.0-FM) and pCAGGS-Flag-La Sota M (pCAGGS-Flag-LM), and the pcDNA3.0-FM has already been constructed and kept in our lab. The full length of chELAVL4 was cloned into the pCAGGS vector with a HA tag to obtain the plasmid pCAGGS-HA-ELAVL4. The shRNA primers targeting ELAVL4 were designed using the BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer website and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Next, double-stranded shRNA was synthesized and cloned into the plasmid pCD513B-U6-neo to obtain shRNA1, shRNA2, and negative control (NC). All primers used in this study are listed in Table 1, and all recombinant plasmids were verified by sequencing. Cell transfection was performed using the TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

The primers used in this study

| Primers | Sequences (5'-3') | Size (bp) | TM (℃) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCAGGS-HA-ELAVL4-F | CCATCGATATGGAGTGGAATGGCCTGAAGATG | 1159 | 53 |

| pCAGGS-HA-ELAVL4-R | CGGCTAGCTCAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTAGGATTTGTGGGTTTTATTGG | ||

| pCAGGS-Flag-LM-F | GGAATTCATGGACTCATCTAGGACAAT | 1135 | 50 |

| pCAGGS-Flag-LM-R | GAAGATCTTTACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCTTTCTTAAAAGGATTGT | ||

| Luc-FM-F | CCGCTCGAGATGGACTCATCTAGGACAATTG | 567 | 52 |

| Luc-FM-R | TTGCGGCCGCTTCGGCACCACAGTCAAAGAAAC | ||

| Luc-LM-F | CCGCTCGAGATGGACTCATCTAGGACAATTG | 567 | 52 |

| Luc-LM-R | TTGCGGCCGCTTCGGTACCACAGTCAAGGAGAC | ||

| M-F | CCGATCGTCCTACAAGACACAG | 223 | 60 |

| M-R | GGACGCTTCCTAGGCAGAGCAT | ||

| NDV-F | ATGGGCYCCAGAYCTTCTAC | 535 | 55 |

| NDV-R | CTGCCACTGCTAGTTGTGATAATCC | ||

| ELAVL4-F | GGTATCGTATGCCCGTCCAA | 214 | 60 |

| ELAVL4-R | GGCTTCTTCCGCCTCTATTC | ||

| ELAVL4-shRNA1F | GATCCGGAATGGCCTGAAGATGATAA TTCAAGAGATTATCATCTTCAGGCCATTCCTTTTTTg | 63 | 37 |

| ELAVL4-shRNA1R | AATTCAAAAAAGGAATGGCCTGAAGATGATAATTCAAGAGATTATCATCTTCAGGCCATTCCg | ||

| ELAVL4-shRNA2F | GATCCGGAGTCTCTTTGGGAGCATTG TTCAAGAGACAATGCTCCCAAAGAGACTCCTTTTTTg | 63 | 37 |

| ELAVL4-shRNA2R | AATTCAAAAAAGGAGTCTCTTTGGGAGCATTG TTCAAGAGACAATGCTCCCAAAGAGACTCCg | ||

| shRNA-NC-F | GATCCGACCCGGCGACGGGCTAGTCTTCAAGAGAGACTAGCCCGTCGCCGGGTCTTTTTTg | 63 | 37 |

| shRNA-NC-R | AATTCAAAAAAGACCCGGCGACGGGCTAGTC TTCAAGAGAGACTAGCCCGTCGCCGGGTCg | ||

| miR-375-qF | TTTGTTCGTTCGGCTCGCGTTA | 60 |

Virus infection and cell treatment

To validate miR-375 expression in NDV infected cells, DF-1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h, infected with F48E9 or La Sota (0.1 MOI), and collected at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 hpi to analyze miR-375 expression by RT-qPCR. After the transfection of DF-1 cells with miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375, sponge-NC, pCAGGS-HA-ELAVL4, shRNA, or NC plasmids for 24 h, the cells were infected with F48E9 or La Sota (0.1 MOI) and the supernatants were collected at 24, 36, and 48 hpi for viral titration.

NDV replication was investigated after DF-1 cells were treated with the supernatant containing miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375, or sponge-NC for 24 h before infection with F48E9 or La Sota (0.1 MOI) or after incubation with F48E9 or La Sota (0.1 MOI) for 1 h. The supernatant was collected and viral titer changes were evaluated at 24 h after each treatment.

Virus titration

Viral progeny titers were quantified by 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50), fluorescence intensity, or plaque assays. Briefly, the DF-1 cells were seeded in 96-well or 24-well plates at 24 h before virus infection. The supernatant from cell cultures was 10-fold serially diluted and 100 μL/well or 300 μL/well was added to the 96-well or 24-well plates. At 5 d or 3 d post-infection, TCID50 was calculated using the Reed-Muench method 33, the average green fluorescent cell count was determined in each microscopic field as described previously 34, or the plaque forming units (PFU) were computed 35.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The microRNAs were extracted using the miRcute miRNA Isolation Kit, and then cDNA was synthesized using the miRcute miRNA First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, as per the manufacturer's instructions (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). To quantify the viral load or viral mRNA, total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol Reagent, as per the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Then, 2 µg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using a real-time thermocycler (Tianlong, Shaanxi, China) with SYBR green detection. Viral mRNA and miRNA abundances were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized against the level of 28S mRNA.

Immunoblotting

The plasmids miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375 or sponge-NC were co-transfected with pcDNA3.0-FM/pCAGGS-Flag-LM into DF-1 cells for 24 h, and then, the cells were collected as reported previously 36 for detecting M gene expression by immunoblotting.

Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with antibodies, and finally visualized by chemiluminescence (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The antibodies used were anti-HA, anti-Flag, anti-H3, anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG purchased from Quintara Biosciences (Wuhan, China). The densitometric analysis of immunodetected bands was calculated as the relative bands area using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MS, USA).

Luciferase reporter assay

The luciferase reporter assay was performed as previously described 37, with modifications. Briefly, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with 500 ng of the pluc-MF/pluc-ML plasmid and 500 ng of p-miR-375 or p-miR-NC using TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Scientific) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were lysed at 24 h after transfection, and the luciferase activity in total cell lysates was measured using the Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell cycle analysis and cell scratch assay

Flow cytometry with propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to analyze the cell cycle progression as described previously 38. Cells were fixed in 75% ethanol for 2 h, and then rehydrated in PBS at 106 cells/mL. After they were treated with 10 μg/mL PI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min, the cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer or kept in dark conditions on ice or at 4°C for later use. Cell cycles were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer with FlowJo (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

After transfection or pretreatment with DF-1 cells for 24 h in 24-well plates, cell scratches were created using small tips at the same position in each well, and cells were cultivated in an incubator at 37°C. After 24 h, wound healing was observed under a microscope. The wound closure rate (expressed as a percentage) was calculated as the relative wound area using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MS, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). To identify significant differences, means were compared by Student's t-tests for viral load and mRNA levels using Padgraph. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

NDV infection induces the up-regulation of miR-375 expression

Chicken embryos were infected with the velogenic F48E9 strain or lentogenic La Sota strain of NDV with a HA titer of 24. The typical clinical lesions of F48E9 infection, like hemorrhage, were observed, but no observable lesions were observed in La Sota infected chicken embryos or the control (Figure S1A). ND virus were detected in samples infected with F48E9 or La Sota, but not in the control (Figure 1A and figure S1B,C).

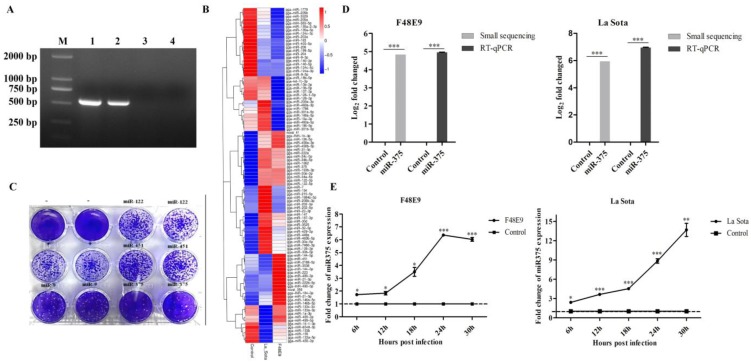

Figure 1.

NDV infection up-regulated miR-375 expression in both chicken embryos and DF-1 cells. (A) PCR detected the NDV in each samples, 1-4 were representative the sample of F48E9, La Sota or PBS infection and negative control, M representative DL5000 DNA Marker. (B) The heatmap of differentially expressed miRNAs in NDV-infected chicken embryonic tissues by small RNA-Seq. (C) Plaques of F48E9 after the overexpression of miR-375, miR-9, miR-122, and miR-451. (D) miR-375 expression levels were assessed by RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR with F48E9 or La Sota infection. (E) Relative expression levels of miR-375 for various infection times were detected in DF-1 cells during F48E9 or La Sota infection. Control representative uninfected group. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns. indicates no significant difference.

A total of 98 differentially expressed miRNAs were screened from small RNA sequencing result (Figure 1B) 39. Intergroup comparisons were used to identify changes in miRNA expression caused by NDV infection. La Sota affected the expression of 61 miRNAs (36 upregulated and 25 downregulated) at 36 hpi, and F48E9 infection altered the expression levels of 64 miRNAs (33 upregulated and 31 downregulated) (Figure 1B and Table S1). The target genes of those miRNAs were further predicted and analyzed by bioinformatics. The obtained results revealed that these miRNAs might involve in regulation cell growth, metabolism, cell cycle, immune and inflammatory responses 39.

miR-375, miR-9, miR-122, and miR-451 exhibited high expression after viral infection and had one or more predicted targets in the NDV genome or anti-genome according to an analysis using BLAST (Figures 1B, S2A). The roles of these four miRNAs in NDV infection were further evaluated in DF-1 cells by transfecting plasmids harboring the transcriptional unit of each. After 24 h post-transfection, DF-1 cells were infected with the F48E9 NDV strain for another 24 h. The results showed that miR-375 resulted in the most significant reduction in NDV proliferation, followed by miR-9 (Figure 1C). The overexpression of miR-122 and miR-451 did not impact NDV growth (Figure 1C). Therefore, we focused on miR-375 in subsequent analyses.

The high level expression of miR-375 detected by small RNA sequencing was further validated by RT-qPCR. Enhanced miR-375 expressions were detected by both methods with slight difference (Figure 1D), which similar with previous reports 40, 41. According to RT-qPCR results, miR-375 expression in all the collected tissues after NDV infection were also increased (Figure S2B). In addition, a gradual increase of miR-375 expression during NDV infection in cells was observed, F48E9, as well as La Sota infection, resulted in a similar miR-375 expression dynamics within 30 hpi (Figure 1E).

Overexpression of miR-375 inhibited NDV proliferation

The growth characteristics of NDV were analyzed in cells with artificially modification miR-375 expression. DF-1 cells were transfected with plasmid expression miR-375 or miR-375 inhibitor, sponge-375 (Figure S1C). NDV infection was performed at 24 h post-transfection. The supernatants were collected at 24, 36, and 48 hpi and viral loads in the supernatants were examined by determining the TCID50.

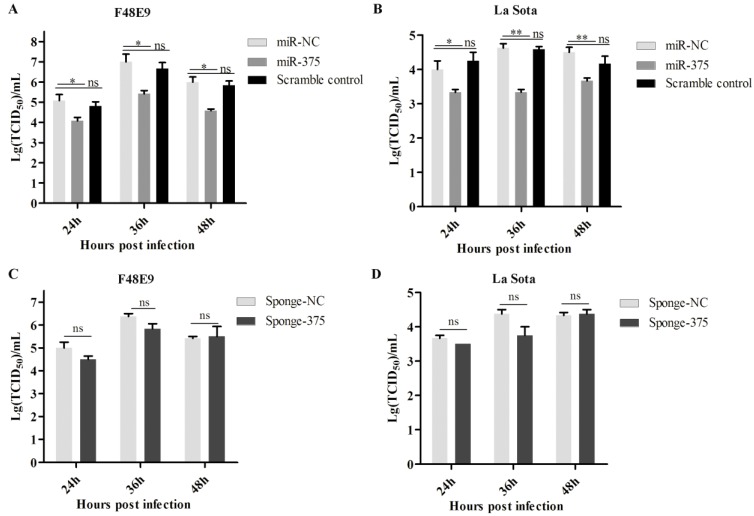

As shown in figure 2, the overexpression of miR-375 decreased NDV F48E9 titers by approximately 10-, 15.8- and 14.2 fold of TCID50 at 24, 36, and 48 hpi, respectively, as compared with the viral titers in the culture medium from infected cells transfected with miR-NC (Figure 2A). The viral titers of NDV La Sota were also reduced by 6.7-, 12.95- and 8.3 fold TCID50 at 24, 36, and 48 hpi (Figure 2B), respectively. Beyond our expectations, down-regulation miR-375 expression with miR-375 sponge, as well as antagomiR-375, did not enhance NDV proliferation (Figures 2C, D, Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Antiviral of miR-375 in DF-1 cells with F48E9 or rLa Sota-GFP infections. DF-1 cells were transfected with plasmids of miR-375, sponge-375, and negative control for 24 h, and infected with F48E9 (0.1 MOI) or rLa Sota-GFP (0.1 MOI) for another 24 h. Viral titers of F48E9 (A, C) and rLa Sota-GFP (B, D) at various infection points were detected using the TCID50 method. Scramble control was mean the control with mutation in binding site of miR-375. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). A statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns. indicates no significant difference.

miR-375 targets the M gene of NDV and leads to its degradation

The seed sequences of miR-375 were used as queries for BLAST searches against the genome and anti-genome of NDVs. One possible target site in the M gene (anti-genome) was identified. As shown in figure 3A, the seed sequences completely matched the M gene (434-440) of F48E9 and six matched the M gene (434-440) of La Sota.

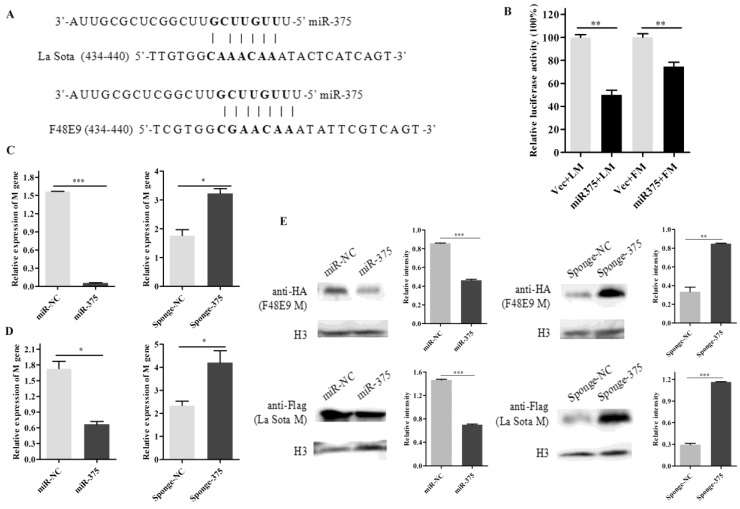

Figure 3.

Degradation of M gene by miR-375. (A) The target sequence of the M gene was predicted using the miRanda algorithm; (B) 500 ng of F48E9 M (FM) or La Sota M (LM) reporter plasmids were co-transfected with 500 ng of miR-375 or miR-NC plasmids (Vec) into the HEK293T cells. Reporter activity was determined at 24 h post-transfection by Beyotime dual-luciferase assays. The plasmids of miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375, or sponge-NC were transfected into DF-1 cells for 24 h, followed by F48E9 (C) or La Sota (D) infection for another 24 h. The cells were collected to detect the M genes of rLa Sota-GFP or F48E9 by RT-qPCR. (E) Western blot analysis of the expression of M gene of F48E9 or La Sota under co-expression with miR-375 or sponge-375. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). A statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns. indicates no significant difference.

To further verify the relationship, a luciferase assay was performed by co-transfecting plasmids psiCheck2-FM/LM and plasmids miR-375 in HEK293T cells. It was found that luciferase activities decreased 35% and 55% for FM and LM, respectively, when plasmid expressing miR-375 was co-transfected (Figure 3B). These results indicated that the predicted target of miR-375 within the M gene of NDV is valid. In a comparison of M gene sequences, we discovered that the seed sequence binding site was relatively highly conserved among NDV strains (Figure S2D).

Moreover, mRNA and protein expression of NDV M gene in cells co-transfected with miR-375/sponge-375 and pcDNA3.0-FM/pCAGGS-Flag-LM were also evaluated. The mRNA expression level of M gene reduced by approximately 33.82-fold for F48E9 and 2.6-fold for La Sota when miR-375 was overexpressed compared with that in control cells, on the contrary, M gene (mRNA level) expression increased approximately 1.82-fold for F48E9 and 1.79-fold for La Sota with interfering miR-375 expression (Figures 3C, D). The western blot analyses were further certified that miR-375 could inhibit the expression of protein M (Figures 3E).

Prediction of the host target of miR-375

The increased expression of miR-375 may also impact the host. Accordingly, host targets of miR-375 were further analyzed using TargetScan. A total of 111 targets were identified (Table S2). Among them, embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila-like RNA binding protein 4 (ELAVL4) was a perfect target with complete seed-matching sites within the 3′ UTR region (Figure 4A). As this interaction has been established previously 42, we did not perform further validation, but focused on revealing the role of ELAVL4 in NDV infection.

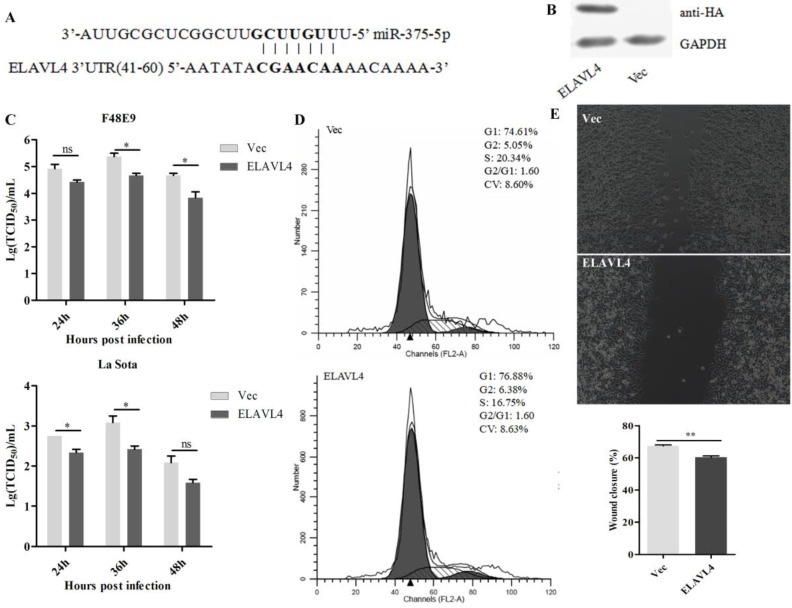

Figure 4.

Antiviral function of ELAVL4 as a miR-375 host target. (A) The target sequence of the ELAVL4 gene was predicted using the miRanda algorithm. (B) The expression of ELAVL4 was detected by western blotting. (C) DF-1 cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA-ELAVL4 and vector plasmids (Vec) for 24 h, and infected with F48E9 (0.1 MOI) or rLa Sota-GFP (0.1 MOI). The viral titers of F48E9 and rLa Sota-GFP at various infection points were detected using the TCID50 method. (D) Flow cytometry was performed to analyze changes in the cell cycle after ELAVL4 overexpression and vector (Vec) transfection. (E) A scratch assay was used to verify cell growth indirectly after ELAVL4 overexpression and vector (Vec) transfection. The wound closure percentage was calculated as the relative wound area using Image J. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns. indicates no significant difference.

The complete open reading frame of ELAVL4 was cloned into a vector and the recombinant plasmids were transfected into DF-1 cells (Figure 4B). NDV infections were conducted at 24 h post-transfection and the supernatants were collected at 24, 36, and 48 hpi. Viral loads in the supernatants were further analyzed by evaluating the TCID50. Overexpression of ELAVL4 could significantly down-regulate NDV proliferation at the late infection stage, i.e., 24, 36, and 48 hpi (Figure 4C), but not at early time points, i.e., 12 hpi. As the cells transfected with the plasmid over-expressing ELAVL4 or the empty vector (Vec) looked different in growth and ELAVL4 is involved in the regulation of neuronal development according to previous analyses 43, we speculated that chicken ELAVL4 functions in the regulation of the cell cycle and influences NDV proliferation.

The cell cycle of DF-1 cells transfected with the plasmid harboring ELAVL4 was monitored by flow cytometry. The overexpression of ELAVL4 slowed cell division and proliferation, as evidenced by the decrease in cells at the S and G2 stages at 24 h post-transfection (Figure 4D). Cell scratch experiments were also used to analyze cell division with or without ELAVL4 overexpression. The control scratches on cells transfected with empty plasmids were repaired within 24 h. The cells over-expressing ELAVL4 did not exhibit scratch healing at that time (Figure 4E), indicating reduced cell migration and cell cycle progression.

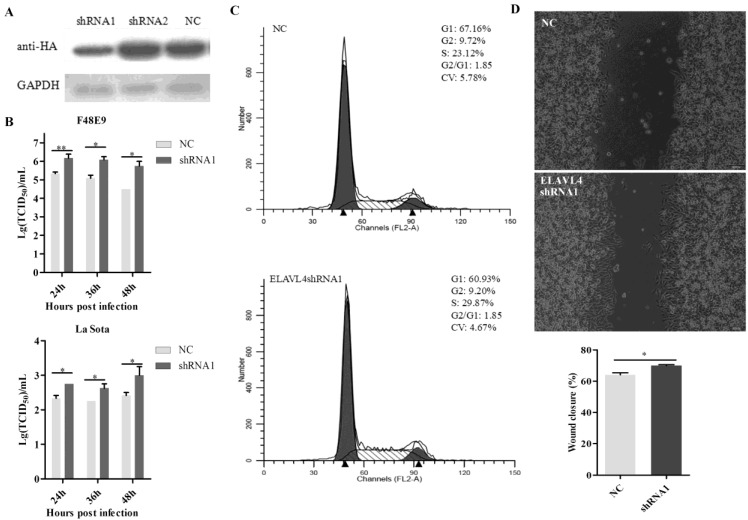

The shRNAs targeting ELAVL4 (sh-ELAVL4) were designed to down-regulate its expression in DF-1 cells. Based on a western blot assay, shRNA1 was more effective than shRNA2 with respect to reducing ELAVL4 expression (Figure 5A). Therefore, shRNA1 was used in further studies. A plasmid expressing shRNA1, p-shRNA1, was transfected into DF-1 cells. NDV growth in cells transfected with p-shRNA1 was also detected. The shRNA-mediated down-regulation of ELAVL4 significantly enhanced both velogenic NDV F48E9 and lentogenic NDV La Sota proliferation in DF-1 cells (Figure 5B). The cell cycles for cells with or without ELAVL4 down-regulation by shRNA were monitored by flow cytometry. The down-regulation of ELAVL4 activated cell division, as evidenced by the increase in cells transfected with p-shRNA1 in the S and G2 stages (Figure 5C). Moreover, accelerated cell scratch healing also demonstrated rapid cell proliferation in the cell scratch assay (Figure 5D) when ELAVL4 was artificially downregulated by shRNA.

Figure 5.

Interference of ELAVL4 could promote NDV proliferation and cell growth. (A) The efficiency of interference of shRNA targeting ELAVL4 was tested by western blotting. (B) DF-1 cells were transfected with ELAVL4-shRNA1 and shRNA-NC plasmids for 24 h, and infected with rLa Sota-GFP or F48E9 (0.1 MOI). The viral titers of F48E9 or rLa Sota-GFP at various infection points were detected using the TCID50 method. (C) Flow cytometry was performed to analyze changes in the cell cycle after ELAVL4-shRNA1 or NC plasmid transfection for 24 h. (D) A scratch assay was used to verify cell growth indirectly after ELAVL4-shRNA1 or NC plasmid transfection for 24 h. The wound closure percentage was calculated as the relative wound area using Image J. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

miR-375 regulated bystander cells

We demonstrated counteracting roles of miR-375 in NDV infection. However, in uninfected cells, miR-375 promotes cell proliferation, which is beneficial for viruses, as more hosts are available in this situation. If miR-375 affects bystander cells surrounding the infected cells, it may have additional implications for NDV. As reported previously, microRNAs are secreted from cells via exosomes; we speculated that miR-375 could also be secreted from infected cells and influence the growth rate of bystander cells.

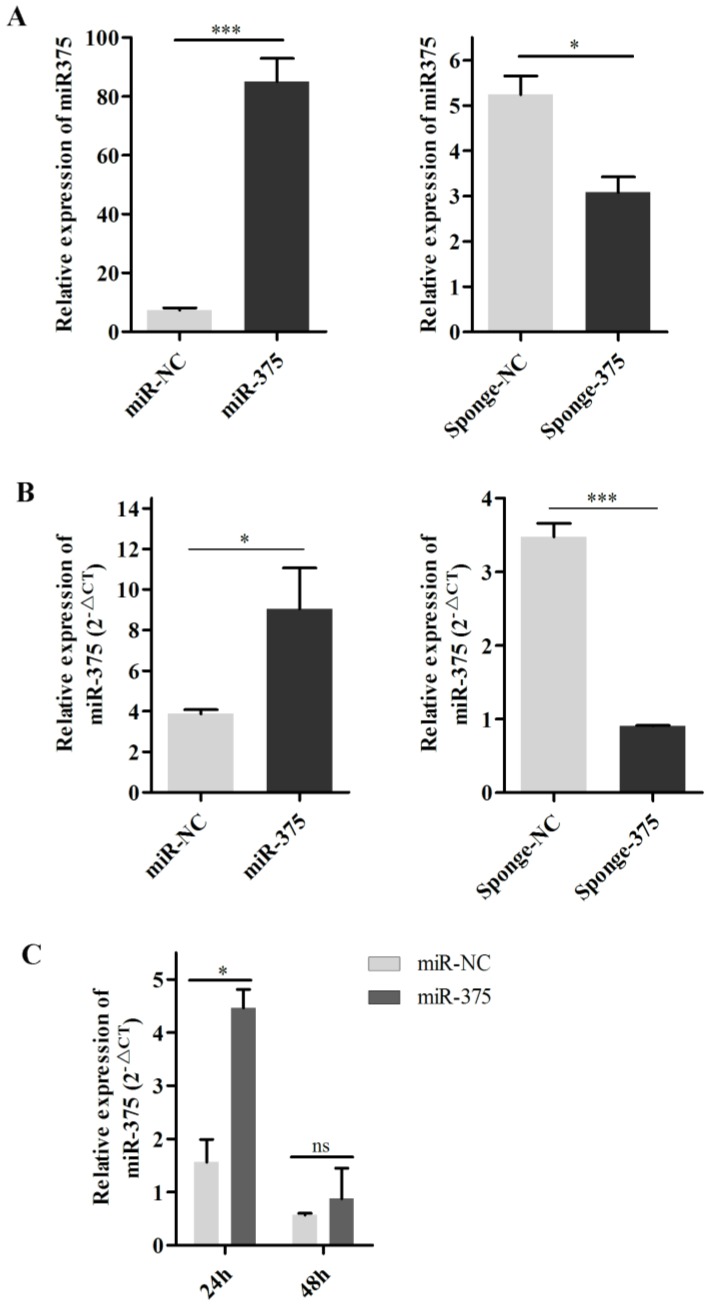

To evaluate this hypothesis, DF-1 cells were transfected with p-miR-375 and RT-qPCR was used to quantify miR-375 in cells and supernatants. Significantly higher levels of miR-375 were detected in cells transfected with p-miR-375 (Figure 6A) and the corresponding supernatants than in untransfected controls (Figure 6B), indicating that miR-375 was secreted from the cells. Additionally, miR-375 in the supernatants decreased to normal levels within 48 h at 37°C (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Secretion of miR375 into the supernatant. miR-375 levels in cells (A) and supernatants (B) after Hep2 cell transfection with the plasmid miR-375, miR-NC sponge-375, or sponge-NC for 24 h. (C) miR-375 was degraded in the supernatant at 37°C for 24 h or 48 h by RT-qPCR. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns. indicates no significant difference.

NDV replication differs between cells treated with miR-375 pre- or post-viral inoculation

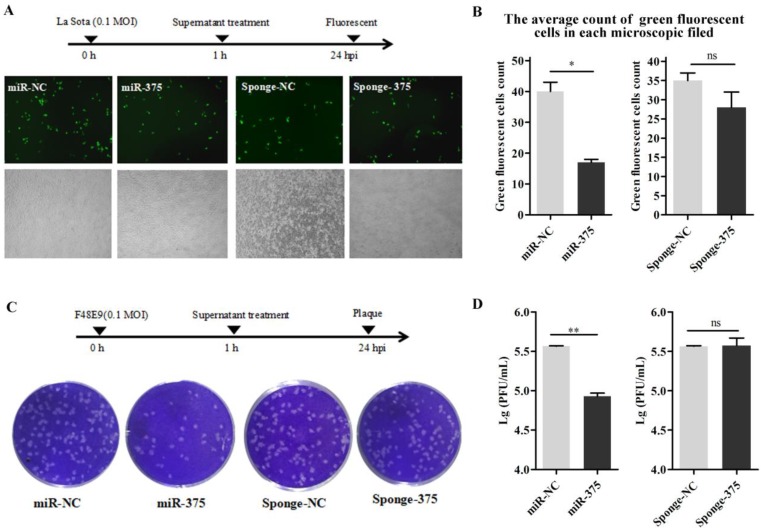

The supernatants containing miR-375 were collected at 24 h from Hep2 cells transfected with p-miR-375. DF-1 cells in 24-well plates were inoculated with NDV; after 1 h, the cells were washed with PBS and 500 μL of the supernatant was added to the wells to treat the infected cells. Viral loads in the medium at 24 h post-inoculation were quantified by counting fluorescent cells (La Sota, Figures 7A, B) or plaques (F48E9, Figures 7C, D). As predicted, cells with supernatants containing miR-375 significantly reduced F48E9 and La Sota proliferation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Treatment of DF-1 cells with miR-375 inhibit NDV replication. The supernatants containing miR375, miR-NC, sponge-375, or sponge-NC were used to culture the DF-1 cells after rLa Sota-GFP or F48E9 was incubated for 1 h. Then, the supernatants were collected for the detection of viral titers at 24 h. A fluorescence microscope was used for observations (A). The average count of fluorescent cells in each microscopic field was calculated (B) for rLa Sota-GFP. Plaques of F48E9 were observed (C) and counted (D). Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns. indicates no significant difference.

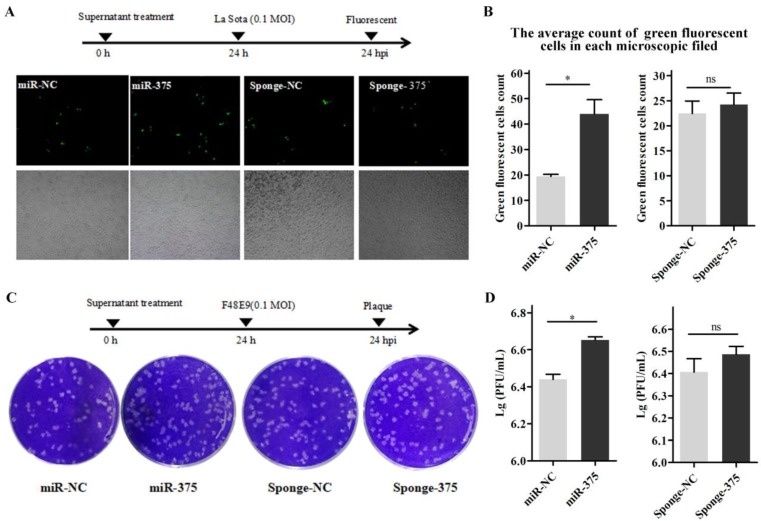

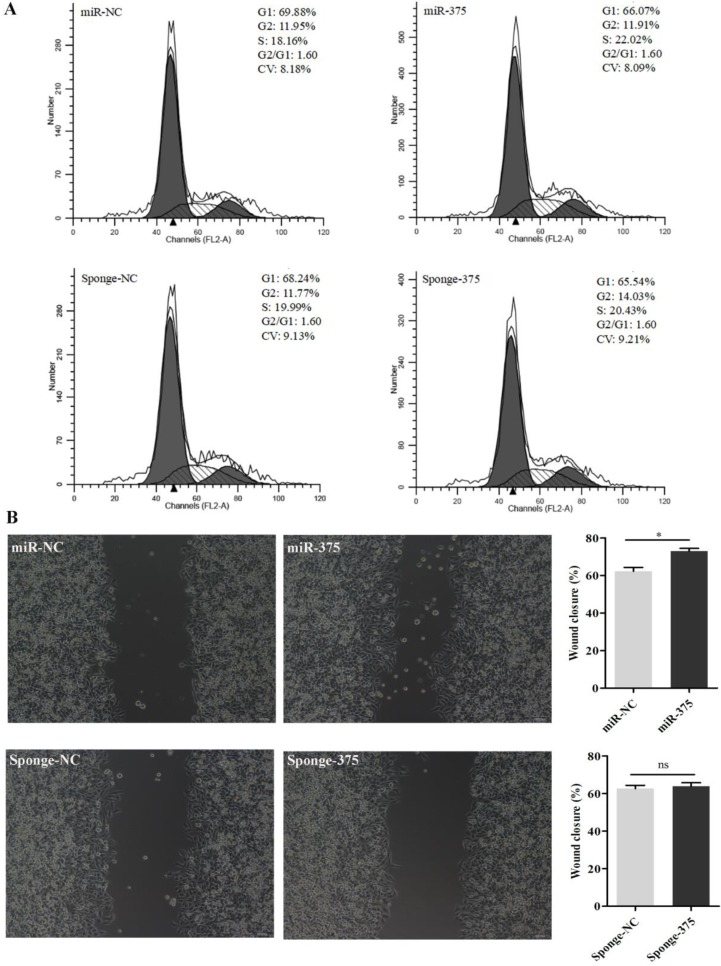

Then, DF-1 cells were pre-treated with the supernatants from Hep2 cells for 24 h and infected with La Sota or F48E9 (0.1 MOI). Similarly, viral loads in the culture media at 24 hpi were quantified by counting fluorescent cells (Figures 8A, B) or plaques (Figures 8C, D). The results showed that the proliferation rates of both La Sota and F48E9 were enhanced by pre-treating cells with supernatants containing miR-375 (Figure 8). Both flow cytometry assays (Figure 9A) and cell scratch assays (Figure 9B) indicated its enhanced cell growth.

Figure 8.

Pre-treatment of DF-1 cells with miR-375 has different effects on NDV proliferation. Supernatants containing miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375, or sponge-NC were used to culture the DF-1 cells at 24 h before incubation with rLa Sota-GFP or F48E9. After another 24 h post-NDV infection, the viral titers were evaluated. Observations (A) and quantitative analyses (B) of fluorescent cells infected with rLa Sota-GFP, and observations (C) and statistical analyses (D) for the plaque assay for F48E9 infection are shown. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, ns. indicates no significant difference.

Figure 9.

Analysis of the cell cycle and wound healing for DF1 cells pretreated with miR-375 or sponge-375. Cell cycle analyses (A) and scratch assays (B) were performed using miR-375, miR-NC, sponge-375, or sponge-NC pretreated DF1 cells. The wound closure percentage was calculated as the relative wound area using Image J. Results are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests: *P < 0.05, ns. indicated no significant difference.

Discussion

MiR-375 was down-regulated in various oncogenic diseases or cancer types according to microarray and deep sequencing analyses 44-46. Yet, it was up-regulated during NDV infection, an oncolytic virus infection. This finding indicated that miR-375 may be useful for NDV-mediated cancer therapy 46, 47. In the current sturdy, we found that La Sota, but not F48E9, infection induces increased levels of miR-375 expression. These results suggested that the up-regulation of miR-375 expression is a slow process. F48E9 failed to induce a higher level of miR-375 expression, possibly because velogenic NDV killed cells too rapidly. Fittingly, La Sota is used more often than F48E9 in cancer therapy.

MiR-375 had an antiviral effect during NDV infection by targeting the M gene of NDV, resulting in gene degradation. The M protein of NDVs is a multi-functional protein involved in virion assembly and budding from the cell membrane 30, 48. Therefore, reduced M protein expression is expected to reduce virus production and release. A similar phenomenon has been reported previously; miR-485 decreases AIV replication and it has a targeting effect via viral BP1 proteins 17. However, in the current study, the down-regulation of miR-375 expression did not promote NDV growth. This may explained by the very low level of endogenic miR-375 expression in normal cells. MiR-375 copies increased from about 27.86 in non-infected tissues to 629.06 and 1419.59 after F48E9 and La Sota infection based on small RNA-seq (Table S1). Eliminating them would have no significant effect on NDV replication. Furthermore, cells have very strong compensatory mechanisms. Each gene may controlled by hundreds of miRNAs, and each miRNA may target hundreds of genes 49. Therefore, it is easy to understand the unexpected results in the context of the large number of regulatory factors that can offset or mask the effects on NDV proliferation.

One of the most impressive findings in our study is the demonstration of secretory microRNA-related regulation of the cell cycle. miRNAs secreted via extracellular vesicles can act a signaling factors and mediate cell communication 50, 51. NDV infection upregulates miR-375 expression in infected cells, and miR-375 secreted by infected cells can mediate the growth of surrounding cells. The enhanced cell growth mediated by secretory miR-375 is beneficial for viral growth. However, miR-375 also has a target in the viral genome. The similar proliferation characteristics of DF-1 cells transfected with plasmids over-expressing miR-375 or treated with the supernatants from Hep2 cells transfected with the plasmid p-miR-375 indicate that miR-375, but not other components, was the functional element. In addition, similar results were obtained for NDV proliferation on cells treated with the transfection plasmid or supernatants from Hep2 cells. As miR-375 in the supernatant from transfected cells is ephemeral, it influences cells, but not NDV. Therefore, cells pretreated with supernatants exhibited enhanced virus proliferation. In addition, a degradation test indicated that miR-375 was significantly reduced at 48 h in the supernatant under 5% CO2 and 37°C. However, additional studies are needed to determine how miR-375 is released from transfected Hep2 cells.

The effect of external secretion from infected cells has also been identified previously, such as EV or paracrine effects 50, 52, 53. It is considered that miRNAs secreted in EVs can be transferred to target cells, and directly modulate target genes 51. For example, viral miRNAs could be secreted from Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells into non-infected cells, resulting in the suppression of viral target genes 52. Infection activates IFN production and the secretory IFNs have antiviral effects via combining with the IFN-alpha/beta receptors on the cell surface, thereby activating the JAK-STAT signaling cascade 54. Then, hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes are expressed to establish an antiviral state after pathway activation in the cells 55, 56. Via these pathways, the uninfected cells could establish an antiviral state, without exposure to the virus. The paracrine effect of inflammatory cytokines also plays an important role in the activation of the inflammatory response 57, 58. Here, we found that miR-375 could be secreted from uninfected cells, affecting NDV infection. These findings suggest that miRNAs may play a larger role in vivo than has been established owing to the effects of their secretion. In previous studies, the functions of miRNAs in infection are frequently evaluated based on a single-step infection analysis. The results of our study indicated that the roles of miRNAs may be distinct during progressive rounds of virus transmission.

ELAVL4, an RNA binding protein, is associated with neurodevelopment and diseases, such as neuronal cell maturation, malignant neuroblastoma, and Parkinson's disease 43, 59-61. ELAVL4 is related to pre-mRNA processing or the enhancement of translation via interactions with eIF4A 62, 63. An overexpression experiment demonstrated that HuD functions in the initiation of neurite outgrowth via, at least in part, its regulation of GAP-43 expression 64. ELAVL4 depletion decreased the proliferation of A549 NSCLC cells, a non-small cell lung cancer cell line, and enhanced the radiation sensitivity of the cells, possibly by increasing apoptotic cell death 65. Contrary to expectations, flow cytometry and scratch-healing assays revealed that the overexpression of ELAVL4 decreased DF-1 cell proliferation. Knocking-down ELAVL4 by shRNA accelerated DF-1 cell growth. Our data provide novel insights into the function of ELAVL4 in normal chicken cells. In future studies, it will be interesting to examine whether ELAVL4 plays different roles in different species and/or tissues. The evolutionary diversification of the HuD/ELAV-like RBP gene family in insects has been identified previously 66.

In the current study, we found that miR-375 could significant reduce NDV proliferation by targeting the M gene of NDV. We also discovered that miR-375 could be externally secreted from DF-1 cells. The released miR-375 could regulate the growth rate of treated cells by targeting ELAVL4 and could influence the proliferation of the virus in the cells. Our results provide novel insights into the function of miRNAs in the regulation of viral infection.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We thank most sincerely Yanhong Wang and Wenbin Wang (Northwest A&F University) for material presentation. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672581 for XLW and 31572538 for ZQY).

Abbreviations

- NDV

Newcastle disease virus

- ELAVL4

embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila-like RNA binding protein 4

- AGO2

Argonaute proteins

- DF-1

chicken embryo fibroblast cells

- HA

hemagglutination assay

- PFU

plaque forming unit

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- TCID50

50% tissue culture infectious dose

- PI

propidium iodide

- EV

extracellular vesicles.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2006;6:259–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang W, Wang YS, Du XN, Liu HJ, Zhang HB. gga-miR-9* inhibits IFN production in antiviral innate immunity by targeting interferon regulatory factor 2 to promote IBDV replication. Veterinary microbiology. 2015;178:41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YAC, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Mature. 2003;425:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim VN. MicroRNA precursors in motion: exportin-5 mediates their nuclear export. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:156–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Gene Dev. 2003;17:3011–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. Rna. 2004;10:185–91. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2014;15:509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni M, Ozgur S, Stoecklin G. On track with P-bodies. Biochem Soc T. 2010;38:242–51. doi: 10.1042/BST0380242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouyang H, He X, Li G, Xu H, Jia X, Nie Q. et al. Deep Sequencing Analysis of miRNA Expression in Breast Muscle of Fast-Growing and Slow-Growing Broilers. International journal of molecular sciences. 2015;16:16242–62. doi: 10.3390/ijms160716242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandiera S, Pernot S, El Saghire H, Durand SC, Thumann C, Crouchet E. et al. Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Upregulation of MicroRNA miR-146a-5p in Hepatocytes Promotes Viral Infection and Deregulates Metabolic Pathways Associated with Liver Disease Pathogenesis. J Virol. 2016;90:6387–400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00619-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J, Xia J, Chen YT, Zhang KY, Zeng Y, Yang Q. H9N2 avian influenza virus enhances the immune responses of BMDCs by down-regulating miR29c. Vaccine. 2017;35:729–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Z, Gao X, Liu C, Lv X, Zheng S. Analysis of microRNA expression profile in specific pathogen-free chickens in response to reticuloendotheliosis virus infection. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2017;101:2767–77. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-8060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conrad KD, Giering F, Erfurth C, Neumann A, Fehr C, Meister G. et al. microRNA-122 Dependent Binding of Ago2 Protein to Hepatitis C Virus RNA Is Associated with Enhanced RNA Stability and Translation Stimulation. Plos One. 2013;8:e56272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng ZH, Ke XL, Wang M, He SY, Li Q, Zheng CS. et al. Human MicroRNA hsa-miR-296-5p Suppresses Enterovirus 71 Replication by Targeting the Viral Genome. Journal of Virology. 2013;87:5645–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02655-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingle H, Kumar S, Raut AA, Mishra A, Kulkarni DD, Kameyama T. et al. The microRNA miR-485 targets host and influenza virus transcripts to regulate antiviral immunity and restrict viral replication. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra126. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thibault PA, Huys A, Amador-Canizares Y, Gailius JE, Pinel DE, Wilson JA. Regulation of Hepatitis C Virus Genome Replication by Xrn1 and MicroRNA-122 Binding to Individual Sites in the 5 ' Untranslated Region. Journal of Virology. 2015;89:6294–311. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03631-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jopling CL. Regulation of hepatitis C virus by microRNA-122. Biochem Soc T. 2008;36:1220–3. doi: 10.1042/BST0361220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad KD, Giering F, Erfurth C, Neumann A, Fehr C, Meister G. et al. microRNA-122 Dependent Binding of Ago2 Protein to Hepatitis C Virus RNA Is Associated with Enhanced RNA Stability and Translation Stimulation (vol 8, e56272, 2013) Plos One. 2016;11:e56272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen WT, He ZJ, Jing QL, Hu YW, Lin CJ, Zhou R. et al. Cellular microRNA-miR-548g-3p modulates the replication of dengue virus. J Infection. 2015;70:631–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang LL, Qin Y, Tong L, Wu S, Wang Q, Jiao QG. et al. MiR-342-5p suppresses coxsackievirus B3 biosynthesis by targeting the 2C-coding region. Antivir Res. 2012;93:270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harden ME, Prasad N, Griffiths A, Munger K. Modulation of microRNA-mRNA Target Pairs by Human Papillomavirus 16 Oncoproteins. mBio. 2017;8:e02170–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02170-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dortmans JC, Koch G, Rottier PJ, Peeters BP. Virulence of Newcastle disease virus: what is known so far? Veterinary research. 2011;42:122. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S, Hao H, Liu Q, Wang R, Zhang P, Wang X. et al. Phylogenetic and pathogenic analyses of two virulent Newcastle disease viruses isolated from Crested Ibis (Nipponia nippon) in China. Virus genes. 2013;46:447–53. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown VR, Bevins SN. A review of virulent Newcastle disease viruses in the United States and the role of wild birds in viral persistence and spread. Veterinary research. 2017;48:68. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganar K, Das M, Sinha S, Kumar S. Newcastle disease virus: current status and our understanding. Virus research. 2014;184:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox RM, Plemper RK. Structure and organization of paramyxovirus particles. Current opinion in virology. 2017;24:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noton SL, Fearns R. Initiation and regulation of paramyxovirus transcription and replication. Virology. 2015;479-480:545–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Duan Z, Chen Y, Liu J, Cheng X, Liu J. et al. Simultaneous mutation of G275A and P276A in the matrix protein of Newcastle disease virus decreases virus replication and budding. Archives of virology. 2016;161:3527–33. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Bi Y, Yu W, Wei N, Wang W, Wei Q. et al. Two mutations in the HR2 region of Newcastle disease virus fusion protein with a cleavage motif "RRQRRL" are critical for fusogenic activity. Virology journal. 2017;14:185. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pizzi M. Sampling variation of the fifty percent end-point, determined by the Reed-Muench (Behrens) method. Human biology. 1950;22:151–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu XS, Zhan Y, Meng CC, Wang JQ, Dong LN, Sun YJ. et al. Identification and functional analysis of phosphorylation in Newcastle disease virus phosphoprotein. Archives of virology. 2016;161:2103–16. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2884-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chia SL, Yusoff K, Shafee N. Viral persistence in colorectal cancer cells infected by Newcastle disease virus. Virology journal. 2014;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng XX, Wang Z, Shi JZ, Deng GH, Kong HH, Tao SY. et al. Glycine at Position 622 in PB1 Contributes to the Virulence of H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus in Mice. Journal of Virology. 2016;90:1872–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02387-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao SQ, Wang X, Ni HB, Li N, Zhang AK, Liu HL. et al. MicroRNA miR-24-3p Promotes Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Replication through Suppression of Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression. Journal of Virology. 2015;89:4494–503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02810-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang QC, Yun XM, Rao WB, Xiao CY. Antioxidative cellular response of lepidopteran ovarian cells to photoactivated alpha-terthienyl. Pestic Biochem Phys. 2017;137:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia YQ, Wang XL, Wang XW, Yan CQ, Lv CJ, Li XQ. et al. Common microRNA(-)mRNA Interactions in Different Newcastle Disease Virus-Infected Chicken Embryonic Visceral Tissues. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19:E1291. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranaware PB, Mishra A, Vijayakumar P, Gandhale PN, Kumar H, Kulkarni DD. et al. Genome Wide Host Gene Expression Analysis in Chicken Lungs Infected with Avian Influenza Viruses. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutejo R, Yeo DS, Myaing MZ, Hui C, Xia J, Ko D. et al. Activation of type I and III interferon signalling pathways occurs in lung epithelial cells infected with low pathogenic avian influenza viruses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdelmohsen K, Hutchison ER, Lee EK, Kuwano Y, Kim MM, Masuda K. et al. miR-375 inhibits differentiation of neurites by lowering HuD levels. Molecular and cellular biology. 2010;30:4197–210. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00316-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bronicki LM, Jasmin BJ. Emerging complexity of the HuD/ELAVl4 gene; implications for neuronal development, function, and dysfunction. Rna. 2013;19:1019–37. doi: 10.1261/rna.039164.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Shang H, Shu D, Zhang H, Ji J, Sun B. et al. gga-miR-375 plays a key role in tumorigenesis post subgroup J avian leukosis virus infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denk J, Boelmans K, Siegismund C, Lassner D, Arlt S, Jahn H. MicroRNA Profiling of CSF Reveals Potential Biomarkers to Detect Alzheimer`s Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zehentmayr F, Hauser-Kronberger C, Zellinger B, Hlubek F, Schuster C, Bodenhofer U. et al. Hsa-miR-375 is a predictor of local control in early stage breast cancer. Clinical epigenetics. 2016;8:28. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0198-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi ZC, Chu XR, Wu YG, Wu JH, Lu CW, Lu RX. et al. MicroRNA-375 functions as a tumor suppressor in osteosarcoma by targeting PIK3CA. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015;36:8579–84. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGinnes LW, Morrison TG. Newcastle disease virus-like particles: preparation, purification, quantification, and incorporation of foreign glycoproteins. Current protocols in microbiology. 2013;30:Unit. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc1802s30. 18 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krutzfeldt J, Stoffel M. MicroRNAs: a new class of regulatory genes affecting metabolism. Cell metabolism. 2006;4:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lotvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzas EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C. et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tkach M, Thery C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell. 2016;164:1226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL. et al. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6328–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bayraktar R, Van Roosbroeck K, Calin GA. Cell-to-cell communication: microRNAs as hormones. Molecular oncology. 2017;11:1673–86. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–83. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoggins JW, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Current opinion in virology. 2011;1:519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sen GC. Novel functions of interferon-induced proteins. Seminars in cancer biology. 2000;10:93–101. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peteranderl C, Morales-Nebreda L, Selvakumar B, Lecuona E, Vadasz I, Morty RE. et al. Macrophage-epithelial paracrine crosstalk inhibits lung edema clearance during influenza infection. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1566–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI83931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai F, Zhu L, Wang F, Shi R, Xie XH, Hong X. et al. The Paracrine Effect of Degenerated Disc Cells on Healthy Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells Is Mediated by MAPK and NF-kappa B Pathways and Can Be Reduced by TGF-beta 1. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36:143–58. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noureddine MA, Qin XJ, Oliveira SA, Skelly TJ, van der Walt J, Hauser MA. et al. Association between the neuron-specific RNA-binding protein ELAVL4 and Parkinson disease. Hum Genet. 2005;117:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeStefano AL, Latourelle J, Lew MF, Suchowersky O, Klein C, Golbe LI. et al. Replication of association between ELAVL4 and Parkinson disease: the GenePD study. Hum Genet. 2008;124:95–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0526-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim C, Lee H, Kang H, Shin JJ, Tak H, Kim W. et al. RNA-binding protein HuD reduces triglyceride production in pancreatic beta cells by enhancing the expression of insulin-induced gene 1. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1859:675–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen CY, Shyu AB. HuD stimulates translation via eIF4A. Molecular cell. 2009;36:920–1. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukao A, Sasano Y, Imataka H, Inoue K, Sakamoto H, Sonenberg N. et al. The ELAV protein HuD stimulates cap-dependent translation in a Poly(A)- and eIF4A-dependent manner. Molecular cell. 2009;36:1007–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tanner DC, Qiu S, Bolognani F, Partridge LD, Weeber EJ, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Alterations in mossy fiber physiology and GAP-43 expression and function in transgenic mice overexpressing HuD. Hippocampus. 2008;18:814–23. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi KJ, Lee JH, Kim KS, Kang S, Lee YS, Bae S. Identification of ELAVL4 as a modulator of radiation sensitivity in A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncology reports. 2011;26:55–63. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe T, Aonuma H. Tissue-specific promoter usage and diverse splicing variants of found in neurons, an ancestral Hu/ELAV-like RNA-binding protein gene of insects, in the direct-developing insect Gryllus bimaculatus. Insect Mol Biol. 2014;23:26–41. doi: 10.1111/imb.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.