Abstract

Numerous studies have confirmed that prelinguistic utterances are precursors to speech, and there is ample evidence that, for example, frequency of canonical syllables and syllable inventory size correlate with speech and language measures at older ages.

Traditionally, prelinguistic utterances have been assessed by phonetic transcription which is difficult and time-consuming in infants. Recently, a more time-efficient methodology to assess prelinguistic utterances in real time, called naturalistic listening, was developed (Ramsdell et al., 2012). In a large international NIDCR-funded randomized controlled trial, Timing of Primary Surgery for with Cleft Palate (TOPS), including many coders, a software program (TimeStamper) was developed to assist in coding of prelinguistic vocalizations in real time, to ensure consistency of the coding procedures. Coders upload a video (or audio) file and watch and listen to the recording in real time without any possibility of pausing or taking notes. In real time, the coder registers each speech-like syllable as canonical or non-canonical. TimeStamper automatically calculates the percentage of canonical syllables of all syllables registered (canonical babbling ratio). At the end of a recording, TimeStamper assists in assessing presence/absence of canonical babbling and syllable inventory size. The software is presented and instructions for free access are provided.

Keywords: Prelinguistic vocalizations, canonical babbling, syllable inventory size, real time listening, TimeStamper

It is well established that prelinguistic vocalizations are precursors to speech. The appearance of adult-like well-formed syllables, canonical syllables, is an important developmental milestone in the first year of life. In typically developing children, it appears no later than at 10 months of age (e.g. Oller, 1980; Stark, 1980). Onset of canonical babbling is a robust milestone and is achieved even in populations regarded as at risk for speech and language disorders due to premature birth, low socioeconomic status and low educational levels (Eilers et al., 1993; Oller, Eilers, Neal, & Cobo-Lewis, 1998; Oller, Eilers, Neal, & Schwartz, 1999). From onset of canonical babbling, the amount of canonical syllables grows and infants’ babbling becomes increasingly complex in structure and resemblance with meaningful speech, as it takes on intonation and stress patterns of mature speech during the first year of life. Thereby, it is possible to assess speech development even before a child says her/his first word.

Amount and diversity of canonical syllables at age 1 have been found to correlate with different speech and language measures at older ages in typically developing children. For instance, 12-month olds with larger syllable inventories produced 50 different words earlier than children with smaller inventories (Menyuk, Liebergott, & Schultz, 1986), and correlations have been reported between larger consonant inventories at age 1 and better articulation skills up to 3 years of age (Menyuk et al., 1986; Vihman & Greenlee, 1987).

Pronounced delays in onset of canonical babbling have consistently been reported in severely hearing impaired infants (e.g. Eilers and Oller, 1994; Schauwers, Gillis, Daemers, De Beukelaer, & Govaerts, 2004; Stoel-Gammon & Otomo, 1986) and in children with William’s syndrome (Masataka, 2001). Patten et al. (2014) studied children later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and reported lower canonical babbling ratios (CBR) in the study group as compared to a control group. Also, studies of children with an unrepaired cleft palate reported a risk for delay in canonical babbling (Chapman, Hardin-Jones, Schulte, & Halter, 2001; Hardin-Jones, Chapman, & Schulte, 2003).

Studies of prelinguistic utterances have almost exclusively used phonetic transcription as a tool. However, this is very time and resource consuming and therefore difficult to use in studies with many participants. Phonetic transcription of prelinguistic vocalizations has also consistently been reported to cause difficulty with agreement between transcribers, especially for non-canonical utterances (Ramsdell, Kimbrough Oller, & Ethington, 2007). Moreover, Ramsdell, Oller, Buder, Ethington, and Chorna (2012) showed that phonetic transcription grossly overestimates parents’ report of their infants’ syllable inventory. Since parents are typically the ones to negotiate word meaning with their child as his/her speech and language develops, overestimation of a child’s productive phonetic inventory may mean any predictions taken from phonetic transcription could be misleading or inaccurate. However, underestimation similarly misrepresents the child’s abilities with attendant implications for analyses and clinical decisions and there are many circumstances where more information may be needed. Thus, users should carefully consider the purpose of their investigation when selecting the assessment method.

We adjusted and tested naturalistic listening in real time from Ramsdell et al. (2012) in a clinical setting using student listeners without experience in infant coding. In naturalistic listening in real time, the coder listens to a sample of recorded speech and assesses a child’s syllable productions continuously without pausing the recording and without taking notes. While listening, canonical and non-canonical syllables are identified. At the end of a recording, the coder lists the syllables she/he found the child produced with control from memory and makes a judgement on presence or absence of canonical babbling.

The students learned the method easily and showed very good inter-rater reliability for syllable inventory in typically developing children and in children with cleft palate (Willadsen et al., 2017). This methodology was then adopted in a large international RCT, Timing of Primary Surgery for with Cleft Palate (TOPS, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00993551), that assesses speech development of 558 infants with cleft palate from 1–5 years of age. We developed a software program, TimeStamper, for the coding procedure of 12-month-olds to equalize assessment conditions.

TimeStamper assists the coder in assessment of canonical babbling in two ways. Firstly, at the end of a recording, the coder makes a judgement of whether or not the child observed was in the canonical babbling stage. Secondly, based on the coder’s assessment of syllable productions, the CBR is calculated automatically by TimeStamper (more detail is provided below). TimeStamper also assists in creating an overview of the child’s syllable inventory regarding size and content.

TimeStamper is written in Java (v1.7) utilizing the video libraries from VLC (http://www.videolan.org/vlc/download-windows.en-GB.html). As such it will run on any operating system that supports Java and that there are VLC libraries compiled for (e.g. Windows and MacOS). The application has no other requirements to run, and the speed of processor and the amount of free memory will determine the quality of the playback experienced by the user. Any computer meeting the minimum requirements for Windows 10 should be able to run the application with no difficulties.

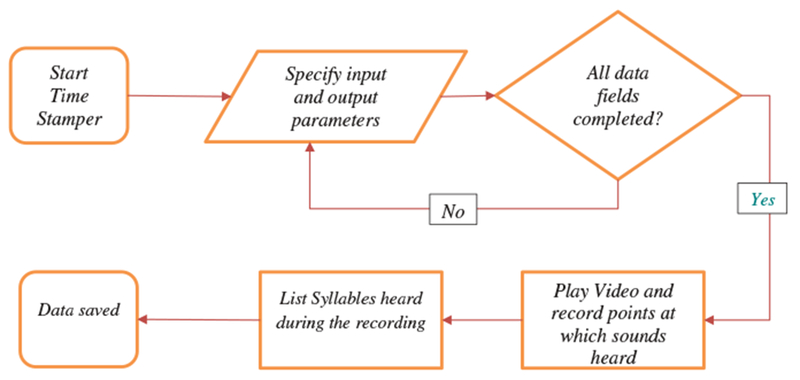

The TimeStamper application can play video (mp4/ogv) or audio (mp3) files and has been designed so as to make the process of assessing sound or video recordings of canonical babbling as straightforward as is possible (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Process flow in TimeStamper.

The end user can configure the application (via a text-based configuration file) to use different keypresses to specify different types of sound (e.g. canonical and non-canonical), with the time point that a key was pressed being stored within the system.

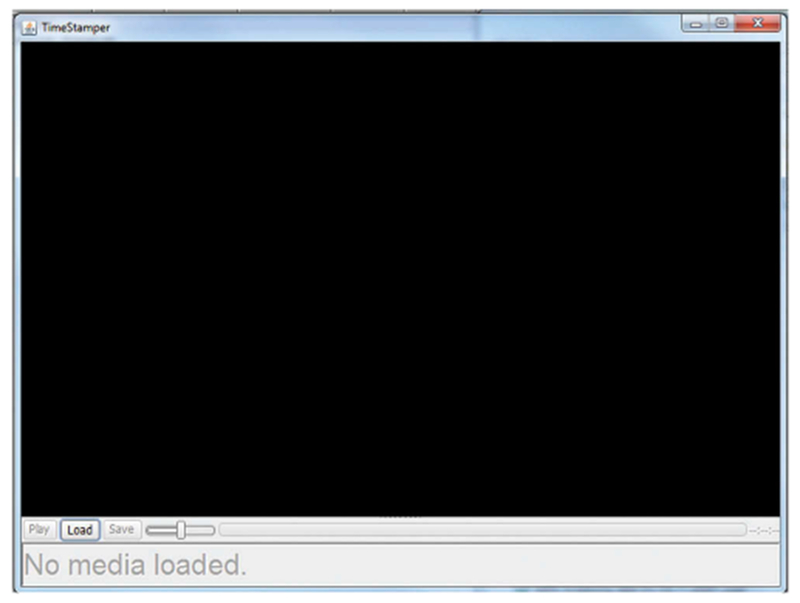

The user interface has been designed to facilitate the analysis of multiple audio/video files by an international assessing team (specifically for the TOPS trial) and the attribution of the results for ease of tracking. When first started, the application will appear as shown in Figure 2. The application will not start in full screen mode by default; however, this is the recommended mode of operation so as to ensure that any keypresses are not missed.

Figure 2.

The home screen for TimeStamper.

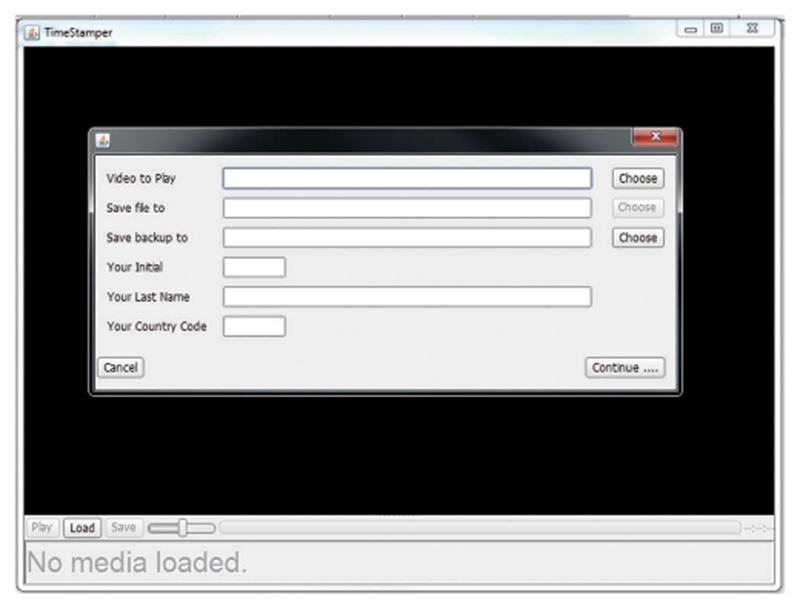

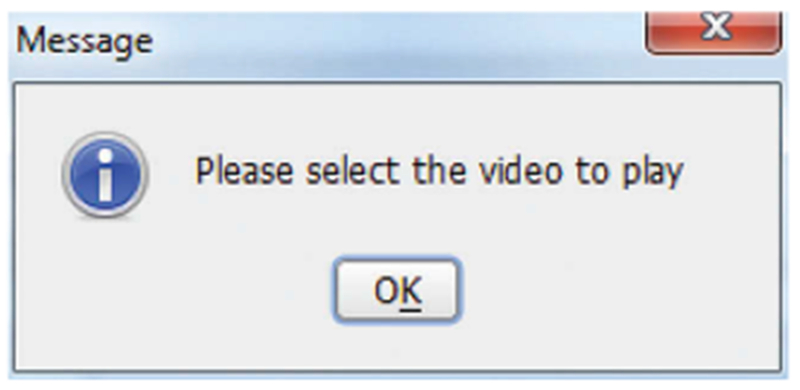

Once launched, the user has only one option, to load a new audio/video file, via the ‘Load’ button (Figure 3). If the user attempts to move forward without completing all of the required, then a warning message is displayed to the user to prompt for completion (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The initial load screen.

Figure 4.

Example for data missing warning.

Once all fields have been completed, the media is loaded and the application is ready for use. The user then commences their assessment. Prior to the assessment commencing, a warning is displayed to ensure that the assessor is aware that sufficient time should be allotted as pausing is not an option. During the assessment, the listener hits a key – default S or L – for each canonical syllable and non-canonical syllable, respectively. The program automatically stamps a time marker for each key strike and also calculates the CBR. A coder can see the count of syllables on the screen so that she/he knows the annotation was registered. However, a coder is only able to see the last annotation to avoid any influence on the final decision of whether or not she/he thinks the child was babbling canonically. At the end of the recording, a window pops up asking the coder to select canonical yes/no, and then to list the syllables she/he found the child produced with control (these syllables are stored in UTF-8 format so as to allow for the use of special characters, such as those used in the International Phonetic Database). When the coder clicks done, the answers are saved automatically in two different locations but not visible to the coder.

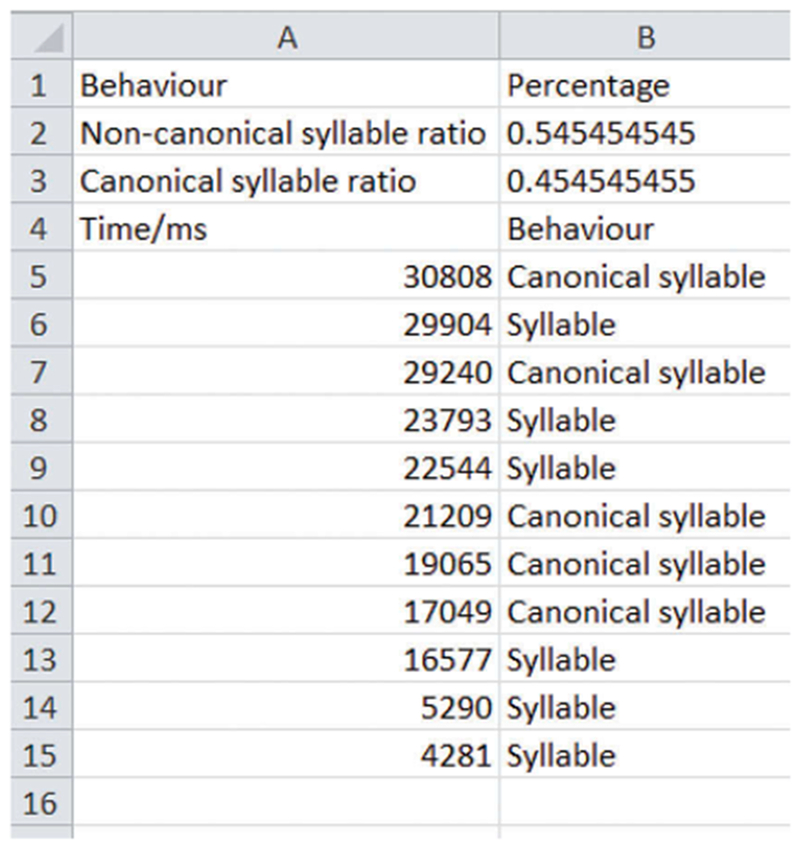

The output from the application is split between the canonical and non-canonical syllables (Figure 5) and calculates the percentage split between the different behaviour types, that is, the CBR (see line 3, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Example for canonical syllable ratio output.

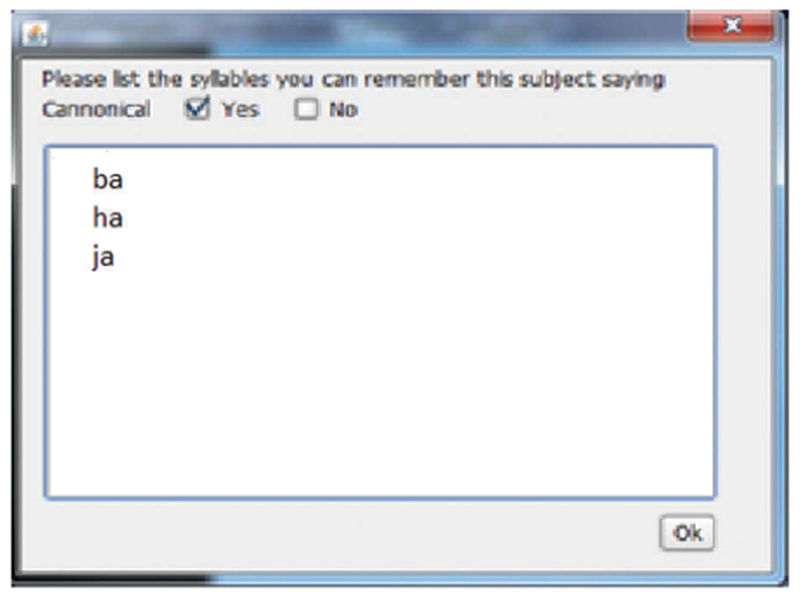

Figure 6 shows a screen shot of pop-up window for information on ‘Canonical yes/no’ and listing of syllables produced with control, for ease of future analysis.

Figure 6.

Example for syllable record screen.

Utilization of this method of storing the results allows for ease of data analysis and attribution to a specific recording and coder. When the recording’s data have been saved, the process can be repeated – the user is reminded at this point that loading a new video will result in all of the previous data being lost.

This tool can be used to assess prelinguistic vocalizations of typically developing infants as well as infants from clinical subgroups with risk of speech and language delay such as children with autism spectrum disorder, hearing impairment and cleft palate. It may be useful in research with many participants and/or many coders, and it may prove valid for audit or quality registries as it is performed in real time. The assessment in real time reduces the time and resource demand markedly (work smarter not harder). With the commonality of output files, it is relatively straightforward to combine the extracts from multiple coders into a single file for a more detailed analysis.

The TimeStamper software can be obtained by contacting ctrcis@liverpool.ac.uk and will be made available for non-commercial use under the terms of the Apache 2.0 License (https://choosealicense.com/license/apache-2.0/), and referencing this paper in any publication arising from the use of this software.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor David K. Oller for his generous help in sharing his knowledge about naturalistic listening in real time. The authors thank Victor Hansen who developed the first version of the TimeStamper software.

Funding

The development of TimeStamper was made possible by Grant Numbers [U01DE018664] and [U01DE018837] from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Footnotes

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/iclp.

Declaration of interest

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDCR.

References

- Chapman KL, Hardin-Jones M, Schulte J, & Halter KA (2001). Vocal development of 9-month-old babies with cleft palate. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(6), 1268–1283. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/099) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers RE, & Oller DK (1994). Infant vocalizations and the early diagnosis of severe hearing impairment. The Journal of Pediatrics, 124(2), 199–203. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70303-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers RE, Oller DK, Levine S, Basinger D, Lynch MP, & Urbano R (1993). The role of prematurity and socioeconomic status in the onset of canonical babbling in infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 16, 297–315. doi: 10.1016/0163-6383(93)80037-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Jones M, Chapman KL, & Schulte J (2003). The impact of cleft type on early vocal development in babies with cleft palate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 40(5), 453–459. doi:10.1597/1545–1569(2003)040<0453:TIOCTO>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masataka N (2001). Why early linguistic milestones are delayed in children with Williams syndrome: Late onset of hand banging as a possible rate-limiting constraint on the emergence of CB. Developmental Science, 4, 158–164. doi: 10.1111/1467-7687.00161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menyuk P, Liebergott J, & Schultz M (1986). Predicting phonological development In Lindblom B & Zetterstrom R (Eds.), Precursors of early speech (vol. 44, pp. 79–93). Houndmills: Stockton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE, Neal AR, & Cobo-Lewis AB (1998). Late onset canonical babbling: A possible early marker of abnormal development. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 103, 249–265. doi:10.1352/0895–8017(1998)103<0249:LOCBAP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE, Neal AR, & Schwartz HK (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 32, 223–246. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9924(99)00013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK (1980). The emergence of the sounds of speech in infancy In Yeni-Komshian G, Kavanagh J, & Ferguson C (Eds.), Child phonology (Vol. 1, pp. 93–112). Production New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patten E, Belardi K, Baranek GT, Watson LR, Labban JD, & Oller DK (2014). Vocal patterns in infants with autism spectrum disorder: Canonical babbling status and vocalization frequency. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2413–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2047-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell HL, Kimbrough Oller D, & Ethington CA (2007). Predicting phonetic transcription agreement: Insights from research in infant vocalizations. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 21(10), 793–831. doi: 10.1080/02699200701547869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell HL, Oller DK, Buder EH, Ethington CA, & Chorna L (2012). Identification of prelinguistic phonological categories. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(6), 1626–1639. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0250) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauwers K, Gillis S, Daemers K, De Beukelaer C, & Govaerts PJ (2004). Cochlear implantation between 5 and 20 months of age: The onset of babbling and the audiologic outcome. Otology & Neurotology, 25(3), 263–270. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark RE (1980). Stages of speech development in the first year of life In Yeni-Komshian G, Kavanagh J, & Ferguson C (Eds.), Child phonology (Vol. 1, pp. 73–90). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C, & Otomo K (1986). Babbling development of hearing impaired and normally hearing subjects. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 51, 33–41. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5101.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihman MM, & Greenlee M (1987). Individual differences in phonological development ages one and three years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 30(4), 503–521. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3004.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willadsen E, Persson MC, Lohmander A, Patrick K, Shaw WC, & Oller DK, (2017, February). Naturalistic assessment of prelinguistic vocalizations in infants with cleft palate: a methodological study. Paper presented at the 13th International Congress of Cleft Lip and Palate and Related Craniofacial Anomalies, Chennai. [Google Scholar]