Significance

Drastic air pollution control in China since 2013 has achieved sharp decreases in fine particulate matter (PM2.5), but ozone pollution has not improved. After removing the effect of meteorological variability, we find that surface ozone has increased in megacity clusters of China, notably Beijing and Shanghai. The increasing trend cannot be simply explained by changes in anthropogenic precursor [NOx and volatile organic compound (VOC)] emissions, particularly in North China Plain (NCP). The most important cause of the increasing ozone in NCP appears to be the decrease in PM2.5, slowing down the sink of hydroperoxy radicals and thus speeding up ozone production. Decreasing ozone in the future will require a combination of NOx and VOC emission controls to overcome the effect of decreasing PM2.5.

Keywords: surface ozone, China, aerosol chemistry, emission reductions, air quality

Abstract

Observations of surface ozone available from ∼1,000 sites across China for the past 5 years (2013–2017) show severe summertime pollution and regionally variable trends. We resolve the effect of meteorological variability on the ozone trends by using a multiple linear regression model. The residual of this regression shows increasing ozone trends of 1–3 ppbv a−1 in megacity clusters of eastern China that we attribute to changes in anthropogenic emissions. By contrast, ozone decreased in some areas of southern China. Anthropogenic NOx emissions in China are estimated to have decreased by 21% during 2013–2017, whereas volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emissions changed little. Decreasing NOx would increase ozone under the VOC-limited conditions thought to prevail in urban China while decreasing ozone under rural NOx-limited conditions. However, simulations with the Goddard Earth Observing System Chemical Transport Model (GEOS-Chem) indicate that a more important factor for ozone trends in the North China Plain is the ∼40% decrease of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) over the 2013–2017 period, slowing down the aerosol sink of hydroperoxy (HO2) radicals and thus stimulating ozone production.

Ozone in surface air is a major air pollutant harmful to human health (1) and to terrestrial vegetation (2, 3). Ozone pollution is a serious issue in China (4–8). Summer mean values of the maximum daily 8-h average (MDA8) ozone concentration exceed 60 ppbv over much of eastern China (9, 10), and episodes exceeding 120 ppbv occur frequently in megacities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (4). Better understanding of the causes of elevated ozone in China is important for developing effective emission control strategies.

Ozone is produced rapidly in polluted air by photochemical oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx ≡ NO + NO2). VOCs originate from both anthropogenic and biogenic sources. NOx is mainly from fuel combustion. Ozone sensitivity to anthropogenic emissions depends on the photochemical regime for ozone formation, i.e., whether ozone production is NOx-limited or VOC-limited (11). Observational and modeling studies suggest that ozone production in urban centers is VOC-limited, whereas ozone production in rural regions is NOx-limited, with megacity cluster regions in a transitional regime (4, 12).

Several studies have reported increasing ozone trends of 1–2 ppbv a−1 at urban and background sites in eastern China over the 2001–2015 period (7, 13–15). Surface ozone data were very sparse before 2013. Starting in 2013 the surface monitoring network greatly expanded, and detailed hourly data across all of China became available from the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment. In the same year, the Chinese government launched the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan to reduce anthropogenic emissions (www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-09/12/content_2486773.htm). Fine particles with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or smaller (PM2.5) concentration has decreased significantly since then, but ozone pollution has not decreased and is seemingly getting worse (8, 16). NOx emissions are estimated to have decreased by more than 20% over 2013–2017 (17), in part to decrease nitrate PM2.5 (18–20), but this could have had a counterproductive effect on ozone under VOC-limited conditions. Decreases in PM2.5 could further affect ozone through changes in aerosol chemistry and photolysis rates (21, 22). On the other hand, meteorological variability could also have a large effect on ozone trends over a 5-y period.

The aim of this work is to better understand the factors controlling ozone trends across China during 2013–2017, separating anthropogenic and meteorological influences, to diagnose the effect of emission reductions even though a 5-y record is relatively short. We focus on the summer season [June–July–August (JJA)] when ozone pollution in eastern China is most severe (4). We use a statistical model to isolate the meteorological contribution to month-to-month variability of ozone and infer a residual trend attributable to anthropogenic emissions. We interpret this residual trend in terms of changing emissions using the Goddard Earth Observing System Chemical Transport Model (GEOS-Chem) driven by 2013–2017 emissions from Multiresolution Emission Inventory for China (MEIC) (17).

Results and Discussion

Observed Summer Ozone Air Quality, Meteorologically Driven Variability, and Residual Trend.

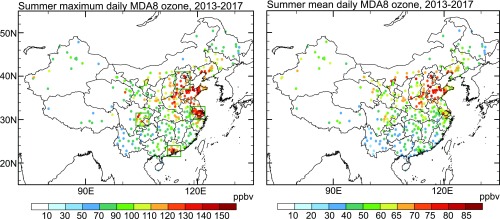

Fig. 1 shows the 5-y average (2013–2017) values of the summer mean and maximum MDA8 ozone at the ensemble of sites operated by the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment. The Chinese National Ambient Air Quality Standard for MDA8 ozone is 160 µg m−3, corresponding to 82 ppbv at 298 K and 1,013 hPa. This standard is exceeded over much of eastern China. The highest concentrations are in the North China Plain, with values as high as 150 ppbv. Summer mean MDA8 ozone is also highest over the North China Plain, with values of 60–80 ppbv.

Fig. 1.

Summer (Left) maximum and (Right) mean values of the MDA8 ozone concentration at the network of sites operated by the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Values are averages over 5 y (JJA 2013–2017) for each city. Rectangles identify the four megacity clusters designated by the Chinese government as targets for air pollution abatement: BTH (37°–41°N, 114°–118°E), YRD (30°–33°N, 118°–122°E), PRD (21.5°–24°N, 112°–115.5°E), and SCB (28.5°–31.5°N, 103.5°–107°E).

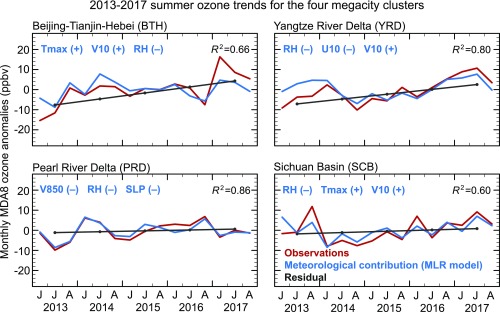

Fig. 2 shows the monthly mean MDA8 ozone trends for 2013–2017 in the four megacity clusters highlighted in Fig. 1: Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH), Yangtze River Delta (YRD), Pearl River Delta (PRD), and Sichuan Basin (SCB). These four megacity clusters are specific target areas in Chinese government plans to decrease air pollution (www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/dqhj/cskqzlzkyb/). The trends are presented as the anomalies for individual summer months relative to their 2013–2017 means. Also shown is the meteorologically driven variability as described by a multiple linear regression (MLR) model considering a number of meteorological variables from the NASA Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2) reanalysis (Methods and Table 1) (23). We use only the top three meteorological predictors for each region (indicated in Fig. 2) to avoid overfitting the data. These include temperature, surface winds, relative humidity, and also surface pressure for PRD. These variables are frequently observed to be correlated with ozone air quality (24) and can be viewed as general indicators of stagnation. Temperature also affects ozone through its control of biogenic VOC emissions and peroxyacetyl nitrate chemistry (25). The coefficients of determination (R2) for the MLR model in fitting the observed ozone anomalies range from 0.60 to 0.86 after removal of the residual linear trends (in black in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Time series of monthly mean MDA8 ozone anomalies in summer (JJA) 2013–2017 for the four megacity clusters of Fig. 1: BTH, YRD. PRD, SCB. MDA8 ozone values for individual 0.5° × 0.625° grid cells are averaged over each cluster and month, and anomalies are computed relative to the 2013–2017 means for that month of the year. In each panel, observations (red line) are compared with results from an MLR model driven by meteorological variability (blue line). The linear trend of the 3-mo average residuals for each year is shown in black. The MLR model uses the top three meteorological predictors (Table 1) for each 0.5° × 0.625° grid cell in the cluster, and the results are then averaged for each cluster. The dominant variables in each cluster are indicated in legend with the sign of their correlation to MDA8 ozone. The coefficients of determination (R2) for the MLR model are shown in the right corner of each plot for the detrended time series (removing the residual linear trend).

Table 1.

Meteorological variables considered as ozone covariates

| Variable name | Description |

| Tmax | Daily maximum 2-m air temperature (K) |

| U10 | 10-m zonal wind (m s−1)* |

| V10 | 10-m meridional wind (m s−1)† |

| PBLH | Mixing depth (m) |

| TCC | Total cloud area fraction (%) |

| Rainfall | Precipitation (mm d−1) |

| SLP | Sea level pressure (Pa) |

| RH | Surface air relative humidity (%) |

| V850 | 850-hPa meridional wind (m s−1)† |

Meteorological data from the NASA MERRA-2 reanalysis (23) with 0.5° × 0.625° grid resolution. The data are averaged over 24 h for use in the MLR model for ozone except for PBLH and TCC, which are averaged over daytime hours (8–20 local time), and for Tmax (daily maximum).

Positive westerly.

Positive southerly.

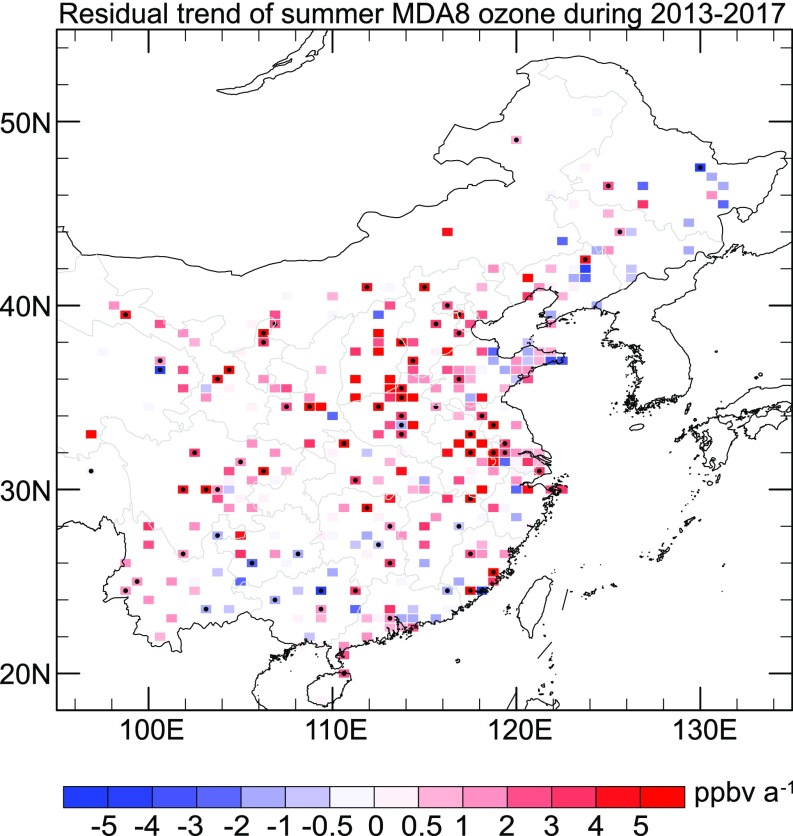

The residual trends in Fig. 2 may be reasonably attributed to the effect of changing anthropogenic emissions. Fig. 3 shows the general trend of this MDA8 ozone residual across China for 2013–2017 after the meteorologically driven variability from the top three variables has been removed for each grid cell with the MLR model. Trends that are statistically significant above the 90% confidence level are marked with black dots. There is a general regional increase in eastern China between Shanghai (YRD) and Beijing (BTH). There are also patterns of decrease in southern and northeastern China away from the major population centers. The average trends for the focus megacity clusters are 3.1 ppbv a−1 for BTH, 2.3 ppbv a−1 for YRD, 0.56 ppbv a−1 for PRD, and 1.6 ppbv a−1 for SCB (SI Appendix, Table S1). The trend in BTH is larger than the earlier 2003–2015 trend of 1.1 ppbv a−1 reported by ref. 14. PRD and SCB show increases even though they are in southern China, indicating some difference between urban centers and the broader region.

Fig. 3.

Residual linear trend of summertime MDA8 ozone for 2013–2017 after removal of meteorological variability. We attribute this residual trend to the effect of changing anthropogenic emissions. Statistically significant trends above the 90% confidence level are marked with black dots.

Anthropogenic Drivers of Ozone Trend.

Chinese anthropogenic emissions estimated in the MEIC inventory decreased by 21% for NOx and increased by 2% for VOCs over the 2013–2017 period (17). Emissions of PM2.5 and its precursors are estimated to have also decreased including by 59% for SO2 (17). Trends for the four megacity cluster regions are given in SI Appendix, Table S2. Observed average PM2.5 levels in summer during 2013–2017 decreased by 41% for BTH, 36% for YRD, 12% for PRD, and 39% for SCB. Aerosol optical depth (AOD) decreased by 20% in eastern China (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

We examined the effects of these changes in NOx emissions, VOC emissions, and PM2.5 levels using the nested-grid GEOS-Chem model version 11-02 over Asia (60°–150°E, 10°S–55°N) with a resolution of 0.5° × 0.625°. The GEOS-Chem model includes detailed ozone–NOx–VOC–aerosol chemistry (26) and has been evaluated in previous studies simulating surface ozone in China (27–30). Our baseline simulation for 2013 is driven by MERRA-2 meteorological data with anthropogenic emissions from the MEIC inventory for China (17) and MIX inventory for other Asian countries (31). SI Appendix, Fig. S2, evaluates the simulation for 2017 with the mean summer MDA8 ozone observations for that year. Observed and simulated concentrations average 58.5 ± 15.4 and 63.0 ± 14.8 ppbv, respectively. Spatial correlation between simulated and observed ozone is high (correlation coefficient R = 0.89).

We then conducted sensitivity simulations with 2013–2017 changes taken together and separately in Chinese NOx and VOC emissions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), PM2.5 affecting aerosol chemistry, and AOD affecting photolysis rates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (Methods). All simulations were performed for the same meteorological conditions of JJA 2013 after 1 mo of initialization. Detailed description of the model configuration and the sensitivity simulations is given in SI Appendix.

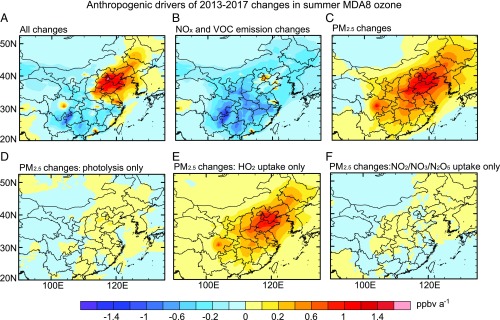

Fig. 4 shows the differences in MDA8 ozone resulting from these 2013–2017 anthropogenic changes. Changes in NOx and VOC emissions (mainly due to decreased NOx emissions; SI Appendix, Fig. S4) increase ozone in the urban areas of BTH, YRD, and PRD and in the broader urban region around Beijing, while decreasing ozone elsewhere, following expected patterns of VOC-limited and NOx-limited conditions. Ozone production in urban areas is expected to be VOC-limited because NOx concentrations are very high, but ozone production on a more regional scale in summer is expected to be NOx-limited. The modeled ozone sensitivity is generally consistent with previous measurement-based, satellite-retrieved, and model inferences of NOx- vs. VOC-limited conditions for ozone production in China (4, 12, 22).

Fig. 4.

Anthropogenic drivers of 2013–2017 changes in mean summertime MDA8 ozone in China. (A–C) GEOS-Chem model results for the changes in MDA8 ozone resulting from: (A) combined effects of 2013–2017 changes in NOx and VOC emissions together with changes in PM2.5, (B) effects of 2013–2017 changes in NOx and VOC emissions alone, and (C) effects of 2013–2017 PM2.5 changes alone including contributions from aerosol chemistry and photolysis rates. (D–F) The different effects of 2013–2017 PM2.5 changes on ozone are separated: (D) radiative effect on photolysis rates, (E) effect of HO2 uptake, and (F) effect of nitrogen oxide (NO2, NO3, and N2O5) uptake.

However, we find that changes in PM2.5 are more important than changes in NOx or VOC emissions in driving ozone trends, particularly in the North China Plain, and this is mainly due to aerosol chemistry rather than photolysis (Fig. 4). The relevant aerosol chemistry involves reactive uptake of the gaseous precursors to ozone formation, as described in GEOS-Chem by first-order reactive uptake coefficients γ (32). This includes reactive uptake of the hydroperoxy radical (HO2) with coefficient γ = 0.2 and conversion to H2O or H2O2 (32–34) and reactive uptake of nitrogen oxides (NO2, NO3, and N2O5) with conversion to HNO3 (32, 35). Uptake of HO2 is by far the dominant effect (Fig. 4). It accounts in the model for most of the sink of hydrogen oxide radicals (HOx ≡ OH + peroxy) in eastern China (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This suppresses the HO2 + NO reaction by which ozone is produced. The effect is particularly important in the North China Plain where PM2.5 concentrations are highest.

The importance of aerosol chemistry as a sink for ozone precursors in China has been previously pointed out in model studies (21, 22), which found ozone decreases of 6–12 and 10–20 ppb, respectively, over eastern China as a result of this chemistry. Ref. 21 found the dominant effect to be the reactive uptake of nitrogen oxides, but we find that effect to be small in part because of VOC-limited conditions and in part because summertime conditions are not conducive to nighttime NO3/N2O5 chemistry.

The HO2 uptake coefficient γ = 0.2 used in our simulation is consistent with a large body of experimental and modeling literature (32). It is specifically consistent with laboratory measurements of HO2 uptake by aerosol particles collected at two mountain sites in eastern China (34), which showed γ values averaging 0.23 ± 0.07 and 0.25 ± 0.09 at each site. Ref. 34 attributed this reactive uptake to aerosol-phase reactions of HO2 with transition metal ions (TMI) and organics. In our standard simulation, we assume that the product of HO2 uptake is H2O, as for example through Cu/Fe TMI catalysis (33):

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

However, if Fe(II) reacts with HO2 instead, then the product becomes H2O2:

| [4] |

We conducted a sensitivity simulation assuming the product to be H2O2 instead of H2O, and this showed no significant difference in results because the recycling of HOx radicals from H2O2 is inefficient (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Overall, the pattern of simulated 2013–2017 ozone trends from the combined changes in emissions and PM2.5 (Fig. 4) is roughly consistent with the observed pattern of residual (presumed anthropogenic) trends in Fig. 3. The largest increases extend from Shanghai (YRD) to the North China Plain. Ozone decreases over most of southern China except in urban regions (as in PRD and SCB). There are some discrepancies between model and observed trends. The model underestimates the observed trend in BTH, possibly because the 50-km grid is too coarse to resolve strongly VOC-limited conditions in urban cores. Observations show ozone increases in western China, whereas the model suggests that emission controls should have produced decreases. Terrain is high in that region so that ozone has a large background component (30), and the increasing trend could reflect the more general trend of increasing background ozone at northern midlatitudes (36). Anthropogenic emissions in western China may also be underestimated (31). Observations show mixed trends in the eastern peninsula of Shandong province as well as decreases in northeastern China that are not captured by the model. Eastern Shandong may be difficult to model due to marine influence. For northeastern China, the model simulates an ozone increase because of the PM2.5 decrease, but it may overestimate the low PM2.5 concentrations in that region (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

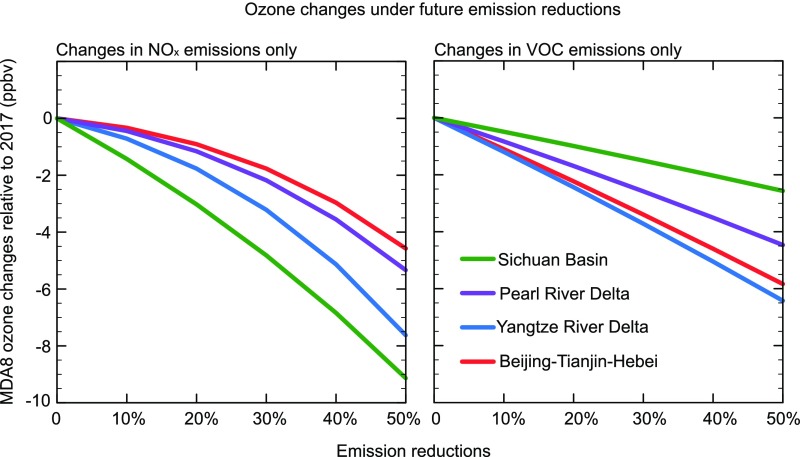

There is a pressing need to continue to decrease PM2.5 levels in China because of the benefit for public health. Our finding that decreasing PM2.5 causes an increase in ozone calls for decreasing NOx and VOC emissions to overcome that effect. Model sensitivity simulations decreasing either NOx or VOC emissions relative to 2017 levels show ozone benefits from both in the four megacity clusters (Fig. 5), consistent with ozone production being in the transitional regime between NOx- and VOC-limited (12). The larger gains are from NOx emission reductions as the chemistry becomes increasingly NOx-limited, but VOC emission reductions are important to decrease ozone in urban cores (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Gains from decreasing NOx and VOC emissions are additive (37); thus, there is benefit in decreasing both.

Fig. 5.

Response of ozone to decreases of anthropogenic NOx and VOC emissions in China relative to 2017 values. Values are GEOS-Chem model results for summertime mean MDA8 ozone in the four megacity clusters of Fig. 1. The simulations decrease either (Left) NOx or (Right) VOC emissions by a uniform fraction across China.

In summary, we analyzed the factors driving 2013–2017 trends in summertime surface ozone pollution across China, taking advantage of the extensive network data available since 2013. We removed the effect of meteorological variability by using a multiple linear regression model fitting surface ozone to meteorological variables. The residual shows an increasing trend of 1–3 ppbv a−1 in urban areas of eastern China that we attribute to changes in anthropogenic emissions. Decrease in anthropogenic NOx emissions can increase ozone in urban areas where ozone production is expected to be VOC-limited. However, we find that a more important and pervasive factor for the increase in ozone in the North China Plain is the rapid decrease in PM2.5, slowing down the reactive uptake of HO2 radicals by aerosol particles and thus stimulating ozone production. Decreasing ozone in the future will require a combination of NOx and VOC emission controls to overcome the effect of decreasing PM2.5. There is a need to better understand HO2 aerosol chemistry and its implications for ozone trends in China. Extending the observational record beyond the relatively short 5-y period will also provide more insights into the factors driving ozone trends in China.

Methods

Data Availability.

All of the measurements, reanalysis data, and GEOS-Chem model code are openly available for download from the websites given below. The anthropogenic emission inventory is available from www.meicmodel.org, and for more information, please contact Q.Z. (qiangzhang@tsinghua.edu.cn).

Surface Ozone Network Data.

Hourly surface ozone concentrations for JJA 2013–2017 were obtained from the public website of the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE): beijingair.sinaapp.com/. The network had 450 monitoring stations in 2013 summer, growing to 1,500 stations by 2017 and including about 330 cities. We average the hourly data on the 0.5° latitude × 0.625° longitude MERRA-2 grid and compute daily MDA8 ozone on that grid. Trend analyses use all available data for a given year. Only using sites with 5-y records does not change the results. Most sites in the four focused megacity clusters were already operational in 2013.

Meteorological Data.

Meteorological fields for 2013–2017 were obtained from the MERRA-2 reanalysis produced by the GEOS of the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (accessible online through https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-2) (23). The MERRA-2 data have a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.625°. They match well with observed daily maximum temperature and relative humidity at Chinese weather stations (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) (38) and provide us with a full gridded ensemble of meteorological variables. We average them over either 24 h or daytime hours (8–20 local time), depending on the variable (Table 1). All data are normalized for use in the MLR model (see below) by subtracting their 2013–2017 mean for that day of the year and dividing by the standard deviation.

Multiple Linear Regression Model.

A number of previous studies have examined meteorological influences on ozone variability in China (4, 9, 39, 40), On the basis of these studies we considered the correlation of MDA8 ozone across China with a large number of candidate meteorological variables from the MERRA-2 archive (SI Appendix, Table S3 and Fig. S9). This led us to adopt nine variables as featuring the strongest correlations (Table 1). We applied a stepwise MLR model for each 0.5° × 0.625° grid cell:

| [5] |

where y is the normalized daily MDA8 ozone concentration and (, …, ) are the nine meteorological variables. The interaction terms are up to second order. The regression coefficients are determined by a stepwise method adding and deleting terms based on Akaike information criterion statistics to obtain the best model fit (41). Similar MLR models have been successfully applied to quantify the effect of meteorological variability on air pollutants in North America, Europe, and China (42–44).

We first apply the MLR model to identify the key meteorological variables driving the variability of daily surface ozone for each grid cell. Only the three locally dominant meteorological variables are regressed onto deseasonalized monthly MDA8 ozone to fit the effect of 2013–2017 meteorological variability on ozone within a 0.5° × 0.625° grid cell. This is done to avoid overfitting. We find that the dominant meteorological variables driving ozone variability are consistent across grid cells on a regional scale.

GEOS-Chem Simulations.

The ozone simulations use the nested-grid version of the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model with detailed oxidant–aerosol chemistry, driven by MERRA-2 assimilated meteorological data and with a horizontal resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° over East Asia (version 11-02; acmg.seas.harvard.edu/geos/). Anthropogenic emissions in China are from the MEIC inventory (see below). The base simulation is for the summer of 2013, and sensitivity simulations examine the effects of 2013–2017 changes in Chinese anthropogenic emissions, PM2.5, and AOD, as described below. Additional sensitivity simulations isolate the effects of PM2.5 and AOD changes on photolysis rates, NOx aerosol chemistry, and HO2 aerosol chemistry. Results presented in Fig. 4 are differences between the sensitivity simulations and the base simulation. Further details on the GEOS-Chem simulations are in SI Appendix.

Anthropogenic Emission Inventory.

The MEIC (www.meicmodel.org) is used to estimate China’s anthropogenic emissions and their trends from 2013 to 2017 (17, 31). MEIC is a widely used bottom-up emission inventory framework that follows a technology-based methodology to calculate emissions from more than 700 anthropogenic source types in China.

PM2.5 and Aerosol Optical Depth Data.

Observed PM2.5 concentrations during 2013–2017 are from the same MEE observation network as ozone. Local changes in PM2.5 concentrations from 2013 to 2017 affecting aerosol chemistry are applied as scaling factors to GEOS-Chem aerosol surface areas in the boundary layer below 1.3 km. AOD trends for 2013–2017 are from the monthly level 3 product of the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument aboard the Aqua satellite, reported at 550-nm wavelength with a resolution of 1° × 1° (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/). These trends in AOD are applied as scaling factors to simulated AOD in the GEOS-Chem calculation of photolysis rates (see details in SI Appendix, sections 1 and 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is a contribution from the Harvard–NUIST Joint Laboratory for Air Quality and Climate. We thank Viral Shah (Harvard University) for helpful discussions. We appreciate the efforts from the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment for supporting the nationwide observation network and publishing hourly air pollutant concentrations. The MEIC emission inventory is developed and managed by researchers at Tsinghua University. All the simulations were run on the Odyssey cluster supported by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Division of Science, Research Computing Group at Harvard University. H.L. is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 91744311.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1812168116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anenberg SC, et al. Global air quality and health co-benefits of mitigating near-term climate change through methane and black carbon emission controls. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:831–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai APK, Martin MV, Heald CL. Threat to future global food security from climate change and ozone air pollution. Nat Clim Chang. 2014;4:817–821. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yue X, et al. Ozone and haze pollution weakens net primary productivity in China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2017;17:6073–6089. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T, et al. Ozone pollution in China: A review of concentrations, meteorological influences, chemical precursors, and effects. Sci Total Environ. 2017;575:1582–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu J, Chen J, Ying Q, Zhang H. One-year simulation of ozone and particulate matter in China using WRF/CMAQ modeling system. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:10333–10350. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, et al. Impacts of biogenic and anthropogenic emissions on summertime ozone formation in the Guanzhong Basin, China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18:7489–7507. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun L, et al. Significant increase of summertime ozone at Mount Tai in central eastern China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:10637–10650. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu X, et al. Severe surface ozone pollution in China: A global perspective. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2018;5:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Z, Wang Y. Influence of the West Pacific subtropical high on surface ozone daily variability in summertime over Eastern China. Atmos Environ. 2017;170:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Liao H. Future ozone air quality and radiative forcing over China owing to future changes in emissions under the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) J Geophys Res Atmos. 2016;121:1978–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinman LI. Low and high NOx tropospheric photochemistry. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1994;99:16831–16838. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin XM, Holloway T. Spatial and temporal variability of ozone sensitivity over China observed from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2015;120:7229–7246. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao W, et al. Long-term trend of O3 in a mega City (Shanghai), China: Characteristics, causes, and interactions with precursors. Sci Total Environ. 2017;603–604:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Z, et al. Significant increase of surface ozone at a rural site, north of Eastern China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:3969–3977. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang G, Li X, Wang Y, Xin J, Ren X. Surface ozone trend details and interpretations in Beijing, 2001–2006. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:8813–8823. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SQ, et al. 2018 The fifth assessment on air quality: Regional air pollution in “2+31” cities during 2013-2017. (Beijing), p 82. Available at www.stat-center.pku.edu.cn/kxyj/yjbg/index.htm. Accessed December 18, 2018.

- 17.Zheng B, et al. Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18:14095–14111. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li K, Liao H, Zhu J, Moch JM. Implications of RCP emissions on future PM2.5 air quality and direct radiative forcing over China. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2016;121:12985–13008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li HY, et al. Nitrate-driven urban haze pollution during summertime over the North China Plain. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18:5293–5306. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, et al. Source attribution of particulate matter pollution over North China with the adjoint method. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10:084011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou S, Liao H, Zhu B. Impacts of aerosols on surface-layer ozone concentrations in China through heterogeneous reactions and changes in photolysis rates. Atmos Environ. 2014;85:123–138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, et al. Radiative and heterogeneous chemical effects of aerosols on ozone and inorganic aerosols over East Asia. Sci Total Environ. 2018;622–623:1327–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelaro R, et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2) J Clim. 2017;30:5419–5454. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob DJ, Winner DA. Effect of climate change on air quality. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob DJ, et al. Factors regulating ozone over the United States and its export to the global atmosphere. J Geophys Res Atmos. 1993;98:14817–14826. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis KR, et al. Why do models overestimate surface ozone in the southeastern United States? Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:13561–13577. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-13561-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, et al. Sensitivity of surface ozone over China to 2000–2050 global changes of climate and emissions. Atmos Environ. 2013;75:374–382. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou S, Liao H, Yang Y, Mu Q. Simulation of the interannual variations of tropospheric ozone over China: Roles of variations in meteorological parameters and anthropogenic emissions. Atmos Environ. 2015;122:839–851. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Liao H, Li J. Impacts of the East Asian summer monsoon on interannual variations of summertime surface-layer ozone concentrations over China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:6867–6879. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni R, Lin J, Yan Y, Lin W. Foreign and domestic contributions to springtime ozone over China. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18:11447–11469. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, et al. MIX: A mosaic Asian anthropogenic emission inventory under the international collaboration framework of the MICS-Asia and HTAP. Atmos Chem Phys. 2017;17:935–963. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob DJ. Heterogeneous chemistry and tropospheric ozone. Atmos Environ. 2000;34:2131–2159. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao J, Fan S, Jacob DJ, Travis KR. Radical loss in the atmosphere from Cu-Fe redox coupling in aerosols. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:509–519. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taketani F, et al. Measurement of overall uptake coefficients for HO2 radicals by aerosol particles sampled from ambient air at Mts. Tai and Mang (China) Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:11907–11916. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans MJ, Jacob DJ. Impact of new laboratory studies of N2O5 hydrolysis on global model budgets of tropospheric nitrogen oxides, ozone, and OH. Geophys Res Lett. 2005;32:L09813. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaudel A, et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Present-day distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone relevant to climate and global atmospheric chemistry model evaluation. Elem Sci Anth. 2018;6:39. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohan DS, Hakami A, Hu Y, Russell AG. Nonlinear response of ozone to emissions: Source apportionment and sensitivity analysis. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:6739–6748. doi: 10.1021/es048664m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du J, Wang K, Wang J, Jiang S, Zhou C. Diurnal cycle of surface air temperature within China in current reanalyses: Evaluation and diagnostics. J Clim. 2018;31:4585–4603. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu J, Xia Z-G, Wang H, Li W. Temporal variations in surface ozone and its precursors and meteorological effects at an urban site in China. Atmos Res. 2007;85:310–337. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu WY, et al. Characteristics of pollutants and their correlation to meteorological conditions at a suburban site in the North China Plain. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:4353–4369. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Springer; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otero N, et al. A multi-model comparison of meteorological drivers of surface ozone over Europe. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18:12269–12288. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tai APK, Mickley LJ, Jacob DJ. Correlations between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and meteorological variables in the United States: Implications for the sensitivity of PM2.5 to climate change. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:3976–3984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, Liao H, Lou S. Increase in winter haze over eastern China in recent decades: Roles of variations in meteorological parameters and anthropogenic emissions. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2016;121:13050–13065. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All of the measurements, reanalysis data, and GEOS-Chem model code are openly available for download from the websites given below. The anthropogenic emission inventory is available from www.meicmodel.org, and for more information, please contact Q.Z. (qiangzhang@tsinghua.edu.cn).