Abstract

Objective

Accelerated long-term forgetting (ALF) occurs when newly learned information decays faster than normal over extended delays. It has been recognised most frequently in temporal lobe epilepsy, including Transient Epileptic Amnesia (TEA), but can also be drug-induced. Little is known about the evolution of ALF over time and its impacts upon other memory functions, such as autobiographical memory (ABM). Here we investigate the long-term outcome of ALF and ABM in a group of patients with TEA and a single case of baclofen-induced ALF.

Methods

Study 1 involved a longitudinal follow-up of 14 patients with TEA over a 10-year period. Patients repeated a neuropsychological battery, three ALF measures (with free recall probed at 30-minutes and 1-week), and a modified Autobiographical Memory Interview. Performance was compared with a group of healthy age-matched controls. In Study 2, patient CS, who previously experienced baclofen-induced ALF, was followed over 4 years, and re-tested now, 18 months after ceasing baclofen. CS repeated a neuropsychological battery, three ALF experimental tasks (each probed after 30 minutes and 1 week), and a modified autobiographical interview. Her performance was compared with healthy age-matched controls.

Results

On ALF measures, the TEA group performed significantly below controls, but when analysed individually, 4 of the 7 patients who originally showed ALF no longer did so. In two, this was accompanied by improvements in ABM for recent but not remote memory. Patient CS no longer demonstrated ALF on standard lab-based tests and now appeared to retain new episodic autobiographical events with a similar degree of episodic richness as controls.

Conclusion

Long-term follow up suggests that ALF can resolve, with improvements translating to recent ABM in some cases.

Keywords: Transient Epileptic Amnesia, accelerated forgetting, memory, Baclofen, long-term amnesia

1. Introduction

Forgetting is a normal occurrence in everyday life, resulting from decay of memory representations over time (Murre & Dros, 2015), or interference from new information (Wixted, 2004). Forgetting can be increased, however, by brain injury. This most commonly affects memory for new information (anterograde memory), but can also involve previously stored memories (retrograde amnesia), such as in cases of severe traumatic brain injury (Esopenko & Levine, 2017; Piolino et al., 2007) or dementia syndromes (Hornberger & Piguet, 2012; Sadek et al., 2004). In many of these cases, the impairments of encoding and storage are readily captured using standard neuropsychological tests of memory, with either poor immediate recall and/or poor recall after a 30-minute delay (Carlesimo, Sabbadini, Fadda, & Caltagirone, 1995; Levin, High, & Eisenberg, 1988).

By contrast, the phenomenon of “accelerated long-term forgetting” (ALF) refers to a form of abnormal forgetting whereby information is apparently encoded and stored successfully over short periods of time (i.e. standard 30-minute delay periods), but then decays abnormally over a period of days or weeks (Bell & Giovagnoli, 2007; Fitzgerald, Mohamed, Ricci, Thayer, & Miller, 2013; Muhlert & Zeman, 2012; Zeman, Butler, Muhlert, & Milton, 2013). This form of memory disturbance may be missed in routine clinical practice, in the absence of longer testing intervals for recall, often creating a disparity between the difficulties a patient self-reports and those observed on formal testing. With testing at extended delays, however, ALF has been found in a variety of patients, most commonly those with temporal lobe epilepsy (Atherton, Nobre, Zeman, & Butler, 2014; Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Hoefeijzers, Dewar, Della Sala, Butler, & Zeman, 2014; Hoefeijzers, Dewar, Della Sala, Zeman, & Butler, 2013; Miller, Flanagan, Mothakunnel, Mohamed, & Thayer, 2015; Muhlert, Milton, Butler, Kapur, & Zeman, 2010; Zeman et al., 2013), but also in patients following thalamic stroke (Tu, Miller, Piguet, & Hornberger, 2014), electroconvulsive therapy (Lewis & Kopelman, 1998; Squire, 1981), amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (Walsh et al., 2014) and genetically determined Alzheimer’s Disease (Weston et al., 2016), or in the context of memory disturbance associated with therapeutic infusion of the selective gamma amino-butyric acid type B (GABAB) receptor agonist, baclofen (Zeman et al., 2016).

This abnormal pattern of forgetting is of interest, as it suggests a qualitatively different forgetting mechanism from the standard memory models within psychology. While some groups undeniably show structural brain change (in thalamic stroke and dementia), in other cases disrupted cerebral metabolism or seizure activity has been suggested as a cause by interfering with consolidation or memory binding processes (Lewis & Kopelman, 1998; Mayes et al., 2003). In cases of chronic epilepsy, a mix of factors may contribute to the clinical picture, combining temporary disruption from seizures, potential impacts of anti-convulsant medication (Jokeit, Krämer, & Ebner, 2005) and structural changes within the brain (Mayes et al., 2003). Few studies have reported on whether ALF may be successfully treated or on its long-term outcome.

1.1. Transient Epileptic Amnesia

Transient Epileptic Amnesia (TEA) is a form of adult onset temporal lobe epilepsy characterised by brief episodes of amnesia. To meet diagnostic criteria, these episodes must be witnessed, recurring, and arise without disrupting other cognitive functions. Evidence of epilepsy is demonstrated via other clinical features (e.g. lipsmacking, presence of an aura), epileptiform abnormalities on EEG, or through a cessation of attacks in response to anti-convulsant medication (Zeman, Boniface, & Hodges, 1998). Although a relatively recently described condition, over 100 cases have now been reported in the literature, with three large series to date (n=50 from Butler et al., 2007, n=23 out of 30 patients reported in Gallassi, 2006, and n=30 reported by Mosbah et al., 2014). Mechanisms leading to the onset of TEA appear variable, and can include structural abnormalities (Butler et al., 2007; Mosbah et al., 2014), or neurodegenerative disease (Rabinowicz, Starkstein, Leiguarda, & Coleman, 2000), although in the great majority of cases the genesis remains unknown. Between seizures, the experience of a ‘leaky’ memory is commonly reported.

While low dose anticonvulsants usually abolish seizures in TEA (Butler & Zeman, 2011), persistent memory difficulties including autobiographical memory (ABM) impairment (Ioannidis, Balamoutsos, Karabela, Kosmidis, & Karacostas, 2011; Milton et al., 2010), and ALF commonly occur (Atherton et al., 2014; Hoefeijzers et al., 2014, 2013; Muhlert et al., 2010). Although certain anticonvulsants themselves can contribute to memory difficulties (Jokeit et al., 2005), the most commonly used medication in TEA (lamotrigine) is not associated with decrements on neuropsychological testing, and in some cases has led to positive score changes (Eddy, Rickards, & Cavanna, 2011). Approximately 70-80% of TEA patients report a persistent disturbance in ABM and half complain of ALF (Butler et al., 2007; Savage, Butler, Milton, Han, & Zeman, 2017). In contrast, performance on standard neuropsychological tests may be normal or only mildly to moderately impaired (Butler et al., 2007; Kopelman, Panayiotopoulos, & Lewis, 1994; Manes, Graham, Zeman, Calcagno, & Hodges, 2005; Razavi, Barrash, & Paradiso, 2010; Zeman et al., 1998). Measures of IQ typically lie within the above average range and performance on specific neuropsychological domains outside of memory, such asattention, executive function and language skills, also remain intact (Butler et al., 2007; Gallassi, 2006).

1.2. Accelerated forgetting in Transient Epileptic Amnesia

Although studies to date have demonstrated that this process of accelerated forgetting in TEA may begin within 3 to 8 hours of acquisition (Hoefeijzers et al., 2014), irrespective of wakefulness or sleep (Atherton et al., 2016, 2014), no study has yet directly investigated the evolution of ALF over the longer term to determine if such difficulties remain stable or change. This is an important gap to address, as patients often are distressed by their symptoms of ALF. For example, in some cases, patients have reported to us that the onset of these symptoms led them to early retirement due to loss of confidence regarding the reliability of their memory. Understanding whether improvements are to be expected or not is clearly important to future life planning and well-being.

In patients who undergo surgery for intractable temporal lobe epilepsy, there is evidence that after seizures have successfully been controlled, symptoms of ALF which had been experienced prior to surgery can lessen, potentially due to providing a stable environment for "slow" consolidation to occur (Evans, Elliott, Reynders, & Isaac, 2014; Gallassi et al., 2011). Likewise anti-convulsants may help reduce ALF (O’Connor, Sieggreen, Ahern, Schomer, & Mesulam, 1997).

TEA, which has a high rate of seizure cessation using anticonvulsants (Butler et al., 2007), provides a particularly valuable opportunity to examine the long-term prevalence of ALF further. Of the small number of studies which have reviewed TEA patients 6-12 months after commencing anti-convulsant therapy, results suggest that improvements in memory can occur following seizure cessation (Midorikawa & Kawamura, 2008; Mosbah et al., 2014; Razavi et al., 2010). Reduced performances on standard neuropsychological tests of memory may return to normal (Razavi et al., 2010) and patients may report feeling less forgetful (Mosbah et al., 2014), although the patchy loss of personal life events often described by participants persists (Ioannidis et al., 2011; Kapur, Young, Bateman, & Kennedy, 1989; Midorikawa & Kawamura, 2008). Only one case to-date has ever reported recovery of some specific remote episodic memories that had been inaccessible (Milton, Butler, & Zeman, 2011). However, there has not yet been a long-term follow-up on the prognosis of TEA over a number of years, leaving unanswered questions regarding whether ALF deficits remain constant over such a time period and more generally whether TEA is a progressive disorder.

1.3. Baclofen-induced accelerated forgetting

ALF has been shown to result from treatment with baclofen in a recently described case (patient CS) of a medication induced TEA-like syndrome (Zeman et al., 2016), with resolution on drug withdrawal. Baclofen is a GABAB receptor agonist which modulates neural plasticity and memory in animals, but has, to date, received little investigation in humans. In this patient, a high-dose, therapeutic, infusion of baclofen into the cerebrospinal fluid gave rise to: i) repeated, short periods of amnesia, ii) accelerated forgetting over days and iii) a loss of established autobiographical memories. The amnesic episodes and accelerated forgetting remitted on withdrawal of baclofen, while the autobiographical amnesia for recent and remote events persisted. It must be noted, however, that the recent events probed were all encoded while she was still taking high doses of baclofen, which may have interfered with processes of encoding and/or early consolidation.

While Zeman et al. (2016) provide a first insight into the ALF caused by a GABAB receptor agonist, further investigation is needed to determine the longer-term outcome in such cases. Specifically, has CS remained free of ALF following cessation of baclofen, and if so, has a stable, ALF-free environment allowed for improvements in autobiographical memory for recent events?

1.4. Aims

We describe the long-term follow-up of ALF in a series of patients with TEA (Study 1) and in CS (Study 2) to examine longitudinal patterns of long-term forgetting and autobiographical memory performance.

Specifically, the aims of the study were to:

-

1)

Investigate the long-term outcome of ALF in TEA participants over a ten year period;

-

2)

Confirm CS’s continued remission of ALF on standard laboratory-based tests 18 months after final withdrawal from baclofen;

-

3)

Examine whether remission of ALF allows the normal accumulation of autobiographical memories for recent events in both patients with TEA following treatment and CS following withdrawal of baclofen.

We hypothesised that with successful treatment of epilepsy / withdrawal of baclofen, ALF will reduce and the richness of recently encoded ABM will be restored.

2. Study 1 – TEA follow-up: Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

All TEA patients were recruited from The Impairment of Memory in Epilepsy (TIME) database and had previously participated in a large cohort study (Butler et al., 2007). To qualify for this original study (T1), participants met diagnostic criteria for TEA (Zeman et al., 1998).

Matched healthy control participants, with no history of neurological or psychiatric conditions, were recruited either as existing members of the TIME project or as new research volunteers from the Devon community. While an attempt was made to recruit the original controls from the 2007 series to gain longitudinal control data, only three participants from this cohort were available. As a result, control data from each time point are considered separately.

The study was approved by the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom (MREC 03/10/77). All participants gave written, informed consent.

2.2. Neuropsychological measures

The battery of standard neuropsychological tests used at the first time point (T1) (Butler et al., 2007) was repeated in order to confirm the cognitive profile of participants and provide a context by which to measure memory change. This included administration of the following tests:

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)(Wechsler, 1999) or Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR)(Holdnack, 2001) to estimate general intellectual functioning

Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT)(Meyers & Meyers, 1995) copy trial as a measure of visuospatial/visuoconstructional skills.

RCFT – 30-minute free recall, the immediate and delayed recall of a prose passage from the Wechsler Memory Scale (Immediate Story recall; Delayed Story recall) (Wechsler, 1997), and the Warrington Recognition Memory Test (RMT – Words; RMT - Faces)(Warrington, 1984) to measure anterograde memory

Graded Naming Test (GNT)(McKenna & Warrington, 1980; Warrington, 1997) and Graded Faces Test (GFT) (Thompson, Graham, Patterson, Sahakian, & Hodges, 2002) as measures of semantic memory

Letter and animal fluency (Steinberg, Bieliauskas, Smith, & Ivnik, 2005; Tombaugh, Kozak, & Rees, 1999) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test – 64 Card Version (WCST)(Kongs, Thompson, Iverson, & Heaton, 2000) to measure executive function. Here, the total number of categories completed is reported.

Current mood was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS)(Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). To examine changes over time in patients’ perception of their memory, participants were asked to complete the same two measures of subjective memory as at T1: the Very Long Term Memory Questionnaire (VLTMQ) (Butler et al., 2009) for perceived frequency of forgetting personally salient events or facts, and the Everyday Memory Questionnaire (EMQ) (Thompson & Corcoran, 1992) to estimate current frequency of everyday memory failures (e.g. misplacing objects in the home, forgetting names).

2.3. Accelerated forgetting measures

Three tasks to assess accelerated forgetting were administered. In keeping with methodological recommendations for studying ALF, these tasks included assessment of both verbal and visual memory and assessed free recall as well as recognition memory (Elliott, Isaac, & Muhlert, 2014; Geurts, van der Werf, & Kessels, 2015):

-

1)

Word List: 15 words (from the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task) were read aloud at a rate of 1 word per second. Participants were required to repeat the list, with 1 point assigned for each word correctly recalled;

-

2)

Story Recall: a story from the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (Wilson, Cockburn, & Baddeley, 1985), involving 20 story units, was read aloud. Participants were required to repeat the story where 1 point was given for each exact phrasing and 0.5 points were awarded for close approximations (e.g. minor variations in the ordering of the words within the phrase or the use of a very close synonym, such as “spokesperson” instead of “spokesman”; see Supplementary Material for further details); and

-

3)

Designs: 7 simple geometric designs, adapted from the Graham-Kendall Memory for Designs test (Graham, 1960), were presented on a laptop screen, at a rate of 3 seconds per design. After all 7 designs were shown, participants were asked to draw all designs from memory. Each design was scored out of 3, where high scores indicate greater accuracy. Designs were scored according to criteria provided in Supplementary material), with excellent inter-rater reliability confirmed (all r> .87) on a subsample of protocols (34%) scored by a second, blinded rater.

As described by Butler et al. (2007), an optimised learning procedure to equate initial learning was used, wherein stimuli in each task were presented over a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 15 trials until the participant attained 90% accuracy in free recall. Delayed recall was then tested at 30 minutes and after 1 week. The 1-week recall was attained by telephone follow-up. During this follow-up participants were asked to recall the items from each task. Participants were not warned during the encoding phase that they would be asked to recall this information at this time point, only that they would be re-contacted a week later to answer some questions about the session. In an attempt to minimise the potential for additional practice, participants were requested not to rehearse, write down or draw items they had learnt during the intervening week. At this same 1-week follow-up, participants were then given a recognition memory test for each task, involving either Yes/No (for the Word List) or 5-option multiple choice questions (Stories and Design). This diverged slightly from the procedure in the 2007 study, where a further free recall test was given at 3 weeks, with the recognition test administered then. As the results of the 2007 study indicated that ALF was already apparent at 1-week, with little additional information gained by including a longer period, the current study did not include this further delay period.

2.4. Autobiographical memory

To assess autobiographical memory recall, the Modified Autobiographical Memory Interview (MAMI) was re-administered (Butler et al., 2007; Kopelman, Wilson, & Baddeley, 1989). An overall episodic memory score out of 10 was generated for each participant by averaging scores for each decade probed. To specifically examine recent autobiographical memory, a separate score for the episodic recall of the person’s current decade, and that of the decade immediately prior was also examined. No instruction was given to participants regarding whether or not to describe the same episodic events they had described when tested in 2007, although in some cases, participants did so spontaneously. Where time permitted, at the end of the interview, participants were informally quizzed to see if they did recall the specific episodes previously mentioned.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 was used for data analysis. Baseline data collected from the original Butler study (T1) were combined with the newly acquired follow up data (T2). To examine current cognitive performance (T2), between-group comparisons of performance of TEA and the new sample of healthy control participants were performed using either independent sample t-tests or Mann Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Statistical significance was judged as any p values <.05.

Longitudinal change was then assessed within TEA participants using paired sample t-tests to compare test performance at baseline with follow-up scores. To account for changing expectations due to ageing, raw test scores were firstly converted into z-scores based on comparisons with the appropriate healthy matched control data for each time period (the original 2007 controls for T1 and the newly recruited controls for T2). These z-scores were then compared over time. In addition, z-scores were used to identify clinically significant differences for individuals, by observing when an individual (Patient ID) performed more than 2 SDs from the healthy control mean score on any measure.

3. Study 1 – TEA follow-up results

3.1. TEA group demographics and clinical outcome

Fourteen of the original 50 TEA participants (9 male, 5 female; mean age = 78.3 (7.0)) from T1 consented to the follow-up neuropsychological assessment at T2 (see Table 1); 13 original participants had died and the remaining 23 were either unavailable or declined to take part. To assess how representative the T2 responders were of the original cohort, T1 data of these responders (n=14) were compared with the T1 data of all non-responders (n=36). There was no significant difference in age at baseline (t (48) = .57, p =.57), gender (χ2 =.12, p =.73) or epilepsy characteristics regarding number of episodes prior to commencing anticonvulsant therapy (t (48) = -.54, p =.60), response to treatment (χ2= 3.91, p = .27) or presence of other types of seizures (χ2= .68, p =.41). There were also no differences in self-reported mood at T1 (HADs Anxiety: t(48) =-1.15, p=.26; HADs Depression: t(48) = .50, p=.62) and no difference in autobiographical memory performance (overall MAMI: t (46)=-.28, p=.78). Some differences, however were found regarding a slightly higher level of education in responders at T2 (t (48)=-2.18, p = .034) by an average of 2 years, and a slightly higher T1 full scale IQ ( responder IQ = 124 (9.3) vs non-responder IQ = 116 (13.4); t (48) = -2.05, p = .046). Those who responded at T2 were also more likely to have complained of ALF when seen at T1 (79% vs 31%; χ2= 9.43, p=.002) and consistent with this, had higher scores on subjective memory measures (EMQ and VLMTQ) at baseline for T2 responders than non-responders (t (37) = -2.20, p=.034 and t (48) = -3.17, p =.003). Despite this, the only difference on standard memory scores at T1 was in favour of responders on the delayed recall of a story (T2 responder: =13.9 SD = 3.5; non-responder: =10.8 SD = 5.3; t (48) =-2.03, p=.048), suggesting that general memory functioning was not more impaired in those who took part in the follow-up.

Table 1. TEA participant characteristics and memory performance.

| PID | Sex | Age onset | Current age | TEA Duration (yrs) | Current Seizures and treatment | Original Seizure frequency/total seizures | EEG result | ALF status | MAMI – all decades average (/10) |

Impaired (2SDs from HC mean) | MAMI – last 2 decades (/10) |

Impaired (2SDs from HC mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | M | 52 | 77 | 25 | 2014: 1 seizure 2015: 5 seizures CBZ to LEV |

2-3 / month (60 +6 total) | Inconcl. | T1: self-reported ALF T2: poor STM |

T1: 4.14 T2: 4.25 |

T1: Y T2: Y |

T1:0, 8 T2: 6, 2 |

T1: Y, Y T2: Y, Y |

| 10 | F | 66 | 81 | 15 | Seizure-free CBZ, stable |

1-2 / month (36 total) | +ve | T1: no ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 8.43 T2: 5.89 |

T1: N T2: Y |

T1: 5, 9 T2: 5, 6 |

T1: Y,N T2: Y, Y |

| 12 | F | 63 | 78 | 15 | Seizure-free LAM, stable |

2 /yr (2 total) | -ve | T1: no ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 8.86 T2: 9.25 |

T1:N T2: N |

T1 :9, 5 T2: 10, 9 |

T1: N, Y T2: N, N |

| 28 | M | 55 | 69 | 14 | Seizure-free LAM; stable |

2 / month (28 total) | -ve | T1: ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 8.50 T2: 7.29 |

T1:N T2: N |

T1: 10, 5 T2:10, 6 |

T1: N, Y T2: N, Y |

| 31 | F | 57 | 73 | 16 | Seizure-free SVP; stable |

weekly (15 total) | +ve | T1: ALF T2: ALF (stable) |

T1: 7.00 T2: 5.50 |

T1: Y T2: Y |

T1:7, 6 T2: 7, 7 |

T1: Y, Y T2: Y, Y |

| 32 | M | 71 | 86 | 15 | Seizure-free SVP; stable |

2-3 / month (19 total) | ND | T1: self-reported ALF T2: ALF (Designs) |

T1: 4.13 T2: 4.67 |

T1: Y T2: Y |

T1:4, 4 T2: 8, 4 |

T1: Y, Y T2: N, Y |

| 36 | M | 76 | 90 | 14 | Seizure-free PHE, stable |

2 / month (16 total) | -ve | T1: self-reported ALF T2: self-reported ALF |

T1: 7.13 T2: 5.11 |

T1: Y T2: Y |

T1:10 9 T2: 3, 10 |

T1: N, N T2: Y, N |

| 40 | M | 65 | 80 | 15 | >50 seizures 2005-2011: 1/yr; 2012: multiple; 2015: 12 seizures; SVP to LEV |

Quarterly (4 +50 total) | Inconc | T1: self-reported ALF T2: poor STM |

T1: 4.29 T2: 5.00 |

T1: Y T2: Y |

T1:6, 4 T2: 6, 6 |

T1: Y, Y T2: Y, Y |

| 55 | M | 59 | 72 | 13 | Seizure-free CBZ; stable |

Monthly (7 total) | -ve | T1: no self-reported ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 8.43 T2: 8.50 |

T1: N T2: N |

T1:9, 10 T2: 9, 9 |

T1: N, N T2: N, N |

| 82 | M | 65 | 78 | 13 | 2013: 2 seizures; 2015: 2 seizures; LAM increased |

Monthly (35 total) | Inconcl. | T1: ALF T2: ALF (worse) |

T1: 7.71 T2: 7.00 |

T1:Y T2: N |

T1: 5, 5 T2: 5, 0 |

T1: Y, Y T2: Y, Y |

| 90 | M | 60 | 83 | 23 | Seizure-free LAM, stable |

Monthly (50 total) | -ve | T1: ALF T2: no ALF |

T1:7.25 T2: 7.33 |

T1: Y T2: N |

T1: 2, 5 T2: 5, 8 |

T1: Y, Y T2: Y, Y |

| 95 | F | 52 | 87 | 35 | 2015: ?1 seizure CBZ increased |

2 /yr (8 total) | +ve | T1: ALF T2: poor STM |

T1: 7.63 T2: 5.33 |

T1:Y T2: Y |

T1: 9, 10 T2: 8, 6 |

T1: N, N T2: N, Y |

| 112 | M | 54 | 65 | 11 | Seizure-free LAM, stable |

Monthly (6 total) | +ve | T1: ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 7.50 T2: 5.43 |

T1:Y T2: Y |

T1: 10, 4 T2: 4, 10 |

T1: N, Y T2: Y, N |

| 114 | F | 61 | 77 | 16 | 2-3 / yr; no medication | 2-3 / yr (25 +20 total) | -ve | T1: ALF T2: no ALF |

T1: 6.14 T2: 5.13 |

T1:Y T2: Y |

T1: 10, 7 T2: 5, 5 |

T1: N, Y T2: Y, Y |

MAMI = Modified Autobiographical Memory Interview; STM = short term memory; +ve indicates indicative of epilepsy; -ve indicates normal results; inconcl. = inconclusive results (some abnormalities noted but not clearly epileptiform), ND = not done; CBZ = carbamazepine; LAM = lamotrigine; SVP = sodium valproate; PHE = phenytoin; LEV = levetiracetam

From the 24 TEA participants who completed the ALF measures at T1, there were no significant differences in 1-week recall between those participating at T2 (n=9) and those who did not participate (n=15) for any of these measures (all p>.37).

Regarding clinical outcomes for the 14 participants at T2, the majority were seizure-free (n= 9), however, 4 participants had experienced re-emergence of seizures after a period of control (Patient IDs: 9, 40, 82, 95), requiring changes in medication, and 1 reported 2-3 seizures per year since presentation (having not taken anticonvulsants; see Table 1). Only one participant (Patient ID 40) had experienced a large number of (approximately 50) seizures since T1 (with all other cases reporting less than 10 seizures over the 10-year period).

3.2. Healthy controls

Twelve healthy control participants (7 male, 5 female; 3 from T1) were recruited as a comparison at T2. When compared with the T2 TEA sample, there were no significant differences in gender distribution (p=.78), age (p=.10), years of education (p=.23) or IQ (p=.78).

3.3. Neuropsychological outcomes

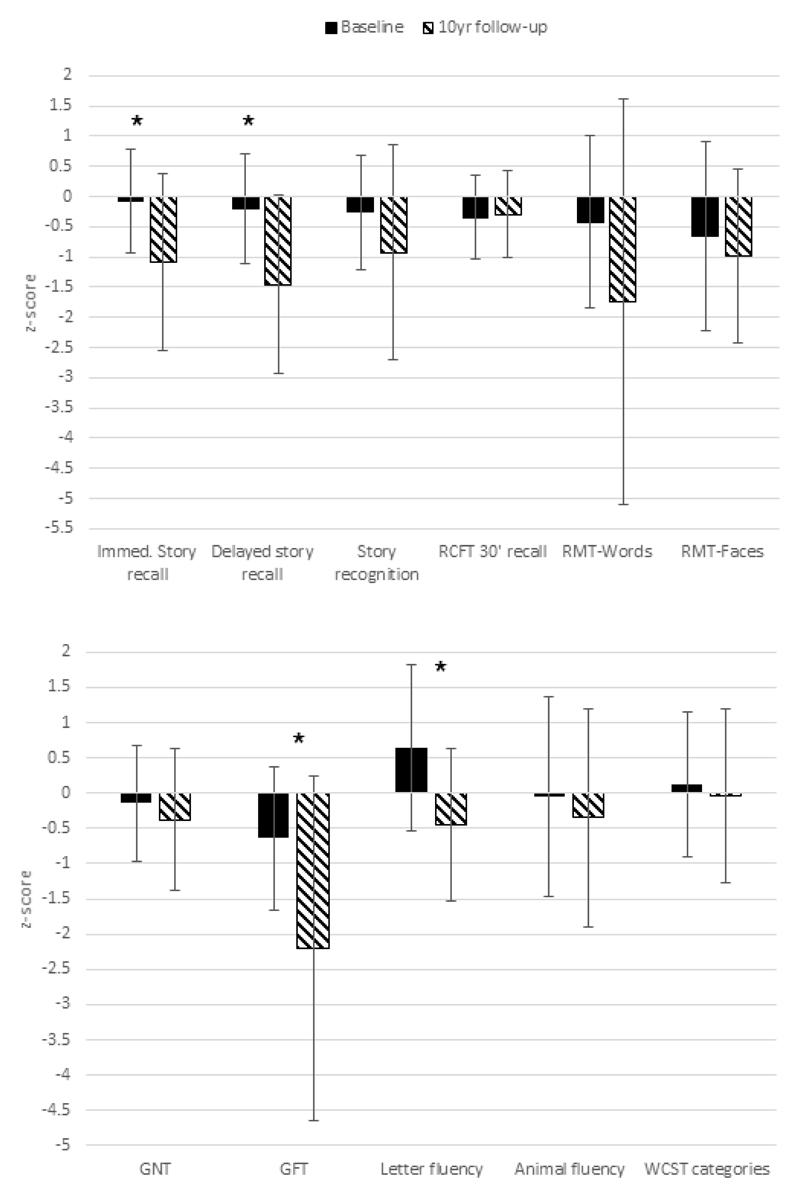

As at T1, TEA participants performed similarly to their matched healthy control peers at T2 on the majority of standard neuropsychological tests (Suppl Table 1). No differences were found with respect to visual recall, object naming, visuoconstructional skills (drawing), or executive function (all p >.29). Poorer performances at T2 were however found on story recall, both at the initial encoding stage (t (24) = 2.12, p =.044, d = 0.85) and after a 30-minute delay (t (24) = 2.85, p=.009, d=1.14), now falling between 1 and 1.5 SDs of the control mean (see Figure 1). This constituted a decline for both measures over time, when comparing TEA z-scores from T1 with z-scores derived at T2 (Immediate recall: p=.013, d=0.76; Delayed recall: p=.001, d=1.07), suggesting the reduction was not simply age-related.

Figure 1.

Neuropsychological test performance over time. Mean z-scores based on comparisons with the appropriate healthy matched control data for each time period. Error bars indicate + one standard deviation. * indicates a significant difference between T1 and T2, p <.05; RCFT = Rey Complex Figure Test; RMT = Recognition Memory Test; GNT = Graded Naming Test; GFT = Graded Faces Test; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

An additional difference was found for recognising famous faces, (GFT: t(17.8)=2.93, p=.006, d=1.18) with the comparison of z-scores between T1 and T2 suggesting a change in performance relative to controls (t(13) = 2.61 ; p=.006, d = .87). This was found even when the task was to provide general information regarding the person, (t(24) = 2.4, p=.024, d =0.97), rather than reflecting only a difficulty with retrieving the name. On another task which involved recognising faces (the Recognition Memory Test for Faces), TEA performance was marginally, although not significantly, reduced compared to the healthy controls (t(23) = 1.97, p=.061). While together these results may suggest emerging difficulties with face processing, some caution is warranted when interpreting the change over time scores. As the mean performance of the T2 healthy controls was higher than the T1 controls, the differences over time between TEA and healthy controls may have been artificially inflated.

When examined at an individual level, by identifying the number of cases at each time point where a person with TEA performed 2SDs or more below the average healthy control level, again, there was no evidence of impairment in overall intellectual functioning (WASI), with all participants maintaining average or above average performances. On standard tests of episodic memory, however, approximately a third (31-38%) showed impairments on one or more measure at T2 relative to healthy controls (as compared to 0-21% at T1 across the same memory measures; see Suppl. Table 2). The most commonly occurring deficits were on the graded faces (54%) and word recognition tasks (38%). Where impairments were observed on multiple memory tests, this occurred most often in those individuals who had experienced seizures in the same year as the follow-up assessment. Despite impairments arising on a range of memory measures, exceptions to this were on recognition memory of the story and recall of visual information, where impairments were rare, and several participants actually gained a higher score on these measures over the 10-year period. Impairments in executive function and object naming were also relatively rare (less than 10% of participants), with up to a quarter of those re-tested improving their scores over time (Suppl Table 2).

TEA participants continued to report difficulties with everyday memory (TEA = 42.67; control = 17.58; EMQ t (22) = -4.32, p <.001, d=1.76) and recall of personally salient events (TEA = 11.08; control = 2.0; VLMTQ t(14.5) = -3.68, p =.002, d=1.50).. Comparing over time, the prevalence of clinically significant, self-reported everyday memory failures (i.e. EMQ scores 2 SDs above controls) remained steady, with 64% of participants at T2 (vs 60% at T1) reporting problems. Reports of very long term memory lapses (VLMTQ), however, appeared to lessen over time in comparison to healthy controls (55% of TEA patients reported an elevated level at T2 vs 77% of cases at T1), with the majority (73%) of TEA participants reporting either a stable level of difficulty, or an improvement in their ability to recall salient, remote memories.

3.4.1. Accelerated forgetting – initial learning

Thirteen of the 14 TEA participants completed the measures of accelerated forgetting at T2, 9 of whom had completed these tasks at T11. Ten of these had previously reported ALF, whereas 3 had not. One of these original ALF reporters at T1 experienced 2 seizures within the year of follow-up assessment. TEA performance was compared with 10 of the matched healthy control participants from T2 (3 of whom had also completed these measures at T1).

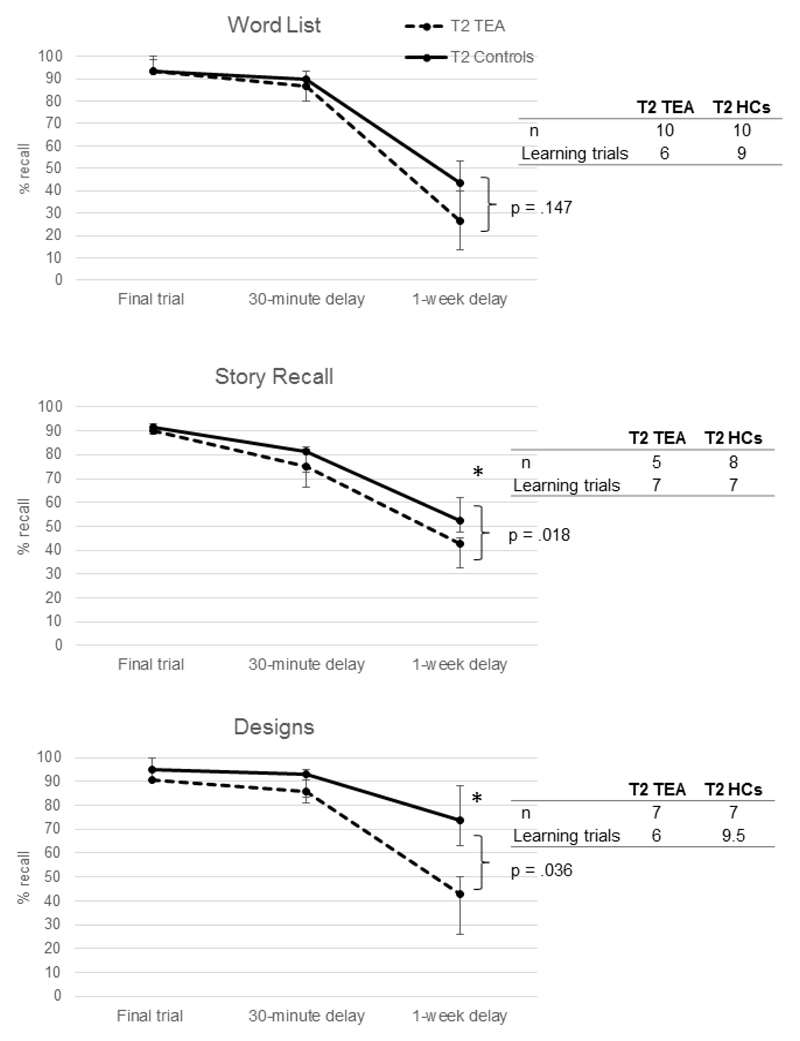

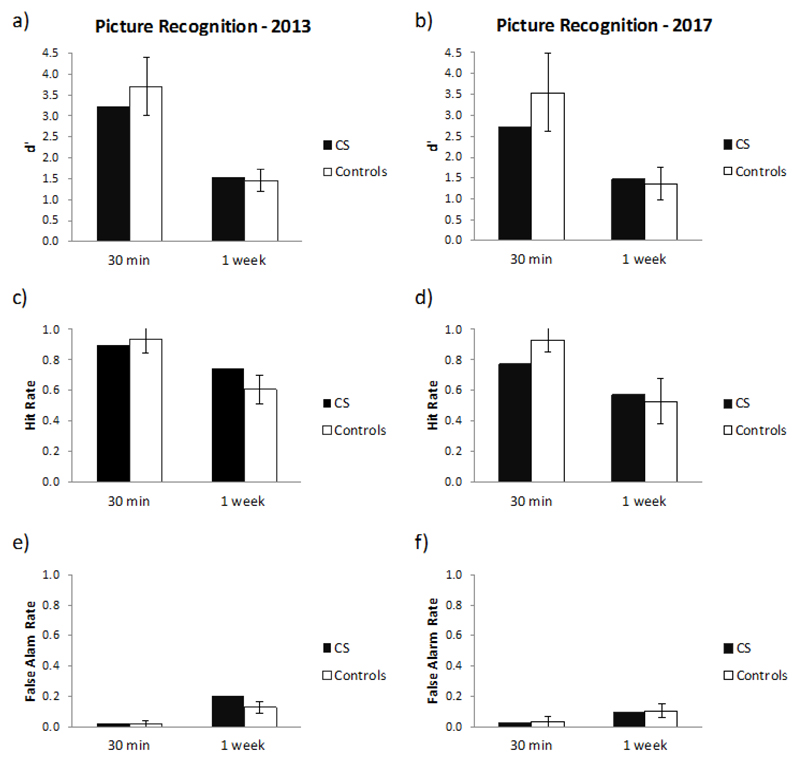

The ability of participants to meet the learning criterion of 90% differed for each task. Only those who could achieve this initial learning goal were entered into the analyses to assess long-term forgetting. This resulted in 10 TEA participants for the Word List task, but only 5 and 7 respectively for the Story Recall and Designs tasks (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Accelerated Forgetting in TEA: Median performance over time. Error bars show interquartile range. * indicates a significant group difference in recall, p <.05; HC = healthy control

3.4.2. Accelerated forgetting – 1-week recall

Given the resulting small sample sizes and non-normal distribution of data, non-parametric (Mann Whitney U) tests were used to compare the TEA group with healthy controls on these measures. For each of the three tasks, there were no significant differences between patients and healthy controls in the maximum score reached at criterion (all p >.23), or the performance at 30-minute delay (all p>.45), indicating similar learning and short-term recall (although healthy controls consistently scored higher at the 30-minute delay, following a tendency to require a greater number of learning trials to meet criteria). At 1-week, a wide range of scores were observed for Word List recall. TEA patients recalled a median of 26.67% of the list, ranging from 0% to 73%; healthy controls recalled a median of 43.33%, ranging from 7-60% recall of the list. When compared directly, no significant group difference was found (U = 31, z = -1.45, p=.147). For the other two ALF tasks, however, TEA patients recalled significantly fewer story details (U = 4, z = -2.36, p=.018; ranging from 5-45% in TEA but 33-68% in healthy controls), and significantly fewer components of the designs than controls (U = 5, z = -2.1, p= .036, ranging from 0-57% in TEA and 29-95% in healthy controls). This provides evidence of continued ALF at the 10-year follow-up, when examined at the group level. Performance on the recognition tests at 1-week, however, revealed no significant group differences for any of the ALF tasks (although Story recognition approached significance at p = .054; see Suppl. Table 3 for group results). This may suggest that the poorer performance on free recall was due to retrieval difficulties rather than “true” forgetting.

We then assessed change over time on these measures (using Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests), and found no significant difference between the 1-week recall z scores acquired at T1 and those from T2 on any of the ALF tests (Word Lists zT1 vs T2 = -1.86, p = .063; Story Recall zT1vsT2 = 0, p =1.0; Designs zT1vsT2 = -.41, p = .66). This suggests that performance on the ALF tasks at a group level was relatively stable.

Examined at an individual level, those who had shown good learning generally performed well at the 30-minute delay. The exceptions were Patient ID 112 on the Story task and Patient ID 12 on the Word List. At the 1-week delay, impaired performances were only observed in 1 of the 5 participants on the Story recall (Patient ID 82), 2 of the 7 patients on the Designs (Patient IDs: 32, 82), and 2 of the 10 patients on the Word List (Patient IDs: 31, 82). Although Patient ID 82 consistently showed ALF on free recall (no words, 1 story detail, 3 design details), recognition memory was less impaired (in that he correctly recognised 47% of the Word list, 73% of the Story and 57% of the Designs).

When examining the performance of the 9 TEA participants who completed these measures at both time points, 4 of the 7 TEA patients who had previously shown ALF at T1 were no longer significantly impaired at 1-week recall on any of the ALF measures (Table 1). This was most evident on the Word List task where improvements in accuracy of free recall at 1-week ranged from between 7% (Patient ID 90) up to 73% (Patient ID 114) greater than what had been recalled at T1. For three of these patients, improvements in raw score accuracy from T1 were observed on all three ALF tasks (Patient IDs: 90,112,114). In the remaining ‘ALF improver’, raw scores were only increased for the Word List tasks (from 13% accuracy to 27% accuracy at 1-week), with raw scores declining on the other two measures.

Of the three patients who continued to show ALF, one (Patient ID 31) performed at a similarly impaired level on the word list (for the other two measures, she failed to meet learning criteria); a further participant’s (Patient ID 82) ALF appeared to have worsened (in that a greater proportion of material was now being forgotten at the 1 week interval – e.g. 1-week recall at T1 was 37% (Story recall), 38% (Designs), 13% (Word List); at T2 this became 5%, 10%, 0%). This was in the context of re-emerged seizures. The remaining TEA patient who showed ALF at T1 was no longer able to show adequate learning in order to assess ALF (that is, Patient ID 95 no longer met the required learning criterion), and consequently showed poor recall at 1-week. Her recognition performance, however, suggested she was only impaired on story recognition (where she scored 67% correct in contrast to the control mean of 97%), having correctly identified 80% of the Word List and 71% of the Designs (where control means were 82% and 81% respectively). The two participants who did not show ALF at T1 (Patient ID 10 and 12) remained free of ALF at T2. Of these two patients, Patient ID 10 now consistently failed to meet learning criteria for these tasks). However, she correctly recognised 80% of the Word List. Patient ID 55 had not been =tested on these measures at T1, and did not show any indications of having developed ALF subsequently.

Overall, this indicates that although TEA patients as a group perform more poorly on measures of ALF than their age-matched peers, some TEA patients may show improvements in their long-term retention of information after the successful cessation of their seizures. ALF does not appear to develop over time in those who do not complain of it at presentation.

3.5. Autobiographical memory

At T2, the significant impairment in autobiographical memory (average MAMI score) which had been observed at T1 remained, with the TEA group continuing to recall fewer episodic details across the lifespan than controls (t(19) =3.75, p=.001, d=1.65). Average episodic recall on this measure declined slightly from T1 to T2 (T1 = 11.08; control = 6.19, T2 = 11.08; control = 5.23), although when comparing z-scores from T1 to T2, recall appeared to have improved over time, as the memory deficit was less pronounced relative to the performance of age-matched controls (p=.038, d=.62). The difference between TEA patients and controls was also less pronounced for the most recent decade, shifting from a score of -5.96 at T1 to -2.31 at T2, which when compared using a paired sample t-test, approached significance (t(13) = -2.07, p = .059).

At an individual level, the majority (62%) of TEA participants continued to perform at least 2 SDs below the healthy control average (compared with 69% of TEA participants at T1) on the overall MAMI measure. In one case (Patient ID 12), ABM episodic recall was above the control mean, with improvement shown in recall of events within the most recent decade. Conversely, in another case (Patient ID 10) declines in performance were apparent (see Table 1).

Of particular interest were the results for the most current decade; 7 individuals improved (e.g. in some cases shifting from over 10 SDs below controls to within 2 SDs of control performance – Patient IDs: 10,32,40,90). When examining autobiographical memory performance in those 4 patients specifically who had improved on measures of ALF, different patterns of results were found. In 2 patients (Patient IDs: 90, 112), improvements in measures of ALF coincided with improvements in episodic recall from the most recent decade (corresponding with the time period over which their seizures had been controlled). For Patient ID 28, normal episodic recall was observed for the previous decade but not the current decade, and in the final ‘ALF improver’ (who was not receiving treatment for seizures – Patient ID114), reductions in episodic recall were observed in both recent decades.

For the one person who experienced worsening ALF (in the context of re-emerging seizures – Patient ID 82), episodic recall for recent events had also declined (from a score of 5/10 to a score of 0), indicating a complete loss of ability to describe recent events. For the one person with stable ALF (Patient ID 31), stable ABM performance was also observed.

When queried about memories recalled at the original assessment (T1), some patients provided good recollection of these same memories (e.g Patient IDs: 12, 90, 95), while others could only provide a more general description of these events (e.g. Patient IDs: 10, 32). In some cases, recall was quite impoverished to the point of no recollection, with one patient (ID 31) commenting “now you are getting into the deep deletion time” and waiting with anticipation for the examiner to tell her what her memory had been.

Overall, these results indicate clear improvement in half of the patients in recalling recent autobiographical events although statistically, as a group, TEA patients remained somewhat poorer than controls. For more remote memories, deficits remained although there was no evidence for a significant decline over time..

4. Study 2 – Baclofen case report: ALF follow-up

In our second study, we investigated the prognosis of ALF and ABM in a case of Baclofen-induced memory disturbance. A full description of the case history and original study can be found in Zeman et al. (2016). A summary is provided below.

4.1. Case history summary

CS is a University educated, business executive who originally presented at age 47 with spasticity affecting her legs and torso following an incomplete spinal cord injury in 2009. As part of her treatment, she was given an intrathecal baclofen pump in 2010, which was effective in controlling her symptoms, but required an increasing dose. While on high doses of baclofen in 2011, CS began to notice a deterioration of memory, particularly in relation to recent events, which she had successfully encoded and maintained over minutes to hours, but would fail to recall beyond this. She also reported difficulty ‘re-experiencing’ remote events, such as foreign holidays or business trips, which she could previously recollect without difficulty, as well as difficulty visualising previously familiar routes around her neighbourhood. After a few months she developed frequently recurring brief amnesic episodes, which would last a few minutes to half an hour and involved both difficulty recalling prior events (retrograde amnesia) and in laying down new memories (anterograde amnesia). She was investigated for TEA, but did not meet the criteria (Zeman et al., 1998), with no indication of epilepsy on either standard or sleep deprived EEG recording, and no positive response to anticonvulsant treatment (indeed, her attack frequency rose while on Lamotrigine). MRI brain scanning revealed no structural abnormality.

Following dose reduction of baclofen, the amnesic episodes ceased almost completely, but after a small increase, returned. CS had a further ~140 episodes of amnesia before withdrawing from baclofen in 2013. Following this, the amnesic episodes ceased. By conducting a series of tailored memory experiments, we clearly documented the presence of ALF while CS was ON baclofen (in 2012) and the cessation of ALF after CS withdrew from Baclofen (i.e. OFF baclofen, in 2013) (Zeman et al., 2016). Despite remission of her ALF, CS’s ability to retain recent autobiographical events remained impaired. This apparent difficulty in recalling personal events, however, may have reflected the disrupted memory processes at the time of encoding (ON baclofen) rather than reflecting her ability at the time of retrieval (OFF baclofen). That is, although her testing occurred after withdrawing from the drug, the events recalled had all occurred during a period when she was on medication, at a time when consolidation could have been negatively impacted..

Between April 2014 and October 2015 CS gradually withdrew from intrathecal baclofen treatment without recurrence of her amnesic episodes or ALF. By July 2014 she had also discontinued treatment with a SSRI antidepressant, sertraline. Her only relevant current treatment is with the benzodiazepine clonazepam, 1mg at night, to reduce spasticity. The current study sought to further investigate her memory, 4 years after her last assessment.

4.2. ALF Materials & Method

Replicating the procedures of 2013, three experiments were conducted to explore patterns in CS’s forgetting of verbal and visual information. In each experiment, material was presented during a learning phase and then subsequently tested at short (30 minute) and long (1-week) delay intervals.

4.2.1. Participants

CS and 5 of the 9 control participants from the original study were re-assessed (4 controls were unavailable for follow-up testing). The 5 controls were healthy individuals (1m/4f) matched for age, education and performance on standard neuropsychological tests with CS (see Table 2). All 5 control participants completed Experiments 1 and 2. For Experiment 3, however, only 4 of the controls had originally completed the task in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 2. Neuropsychological test battery comparing CS and healthy control participants over time.

| 2013 | 2017 | 2013 to 2017 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Sample | CS | Significance test | Control Sample | CS | Significance test | CS vs. Controls | |||||||

| Measure | N | Mean | SD | Score | t | p | Mean | SD | Score | t | p | t | p |

| Age | 5 | 51.6 | 2.19 | 51 | -0.25 | 0.815 | 55 | 2.55 | 54 | -0.358 | 0.738 | / | / |

| Education | 5 | 17.6 | 1.52 | 17 | -0.36 | 0.737 | 17.6 | 1.52 | 17 | -0.36 | 0.737 | / | / |

| NART-predicted verbal IQ | 5 | 122.19 | 4.04 | 121.64 | -0.124 | 0.907 | 123.3 | 4.13 | 119.8 | -0.774 | 0.482 | 3.975 | 0.016 |

| WASI similarities(ASS) | 5 | 13.4 | 1.34 | 14 | 0.409 | 0.704 | 14.2 | 1.64 | 11 | -1.781 | 0.149 | 2.885 | 0.045 |

| WASI matrix reasoning (ASS) | 5 | 13.6 | 1.14 | 15 | 1.121 | 0.325 | 13.6 | 1.82 | 12 | -0.803 | 0.467 | 1.536 | 0.199 |

| Story recall - immediate (25) | 5 | 17.2 | 2.77 | 20 | 0.923 | 0.408 | 20.2 | 2.39 | 18 | -0.84 | 0.448 | 1.312 | 0.260 |

| Story recall - delayed (25) | 5 | 17.8 | 1.92 | 20 | 1.046 | 0.355 | 18.2 | 2.39 | 14 | -1.604 | 0.184 | 2.572 | 0.062 |

| Story recall - % retention | 5 | 99.05 | 2.13 | 100 | 0.407 | 0.705 | 90.04 | 3.64 | 77.78 | -3.075 | 0.037 | 1.975 | 0.120 |

| Story recall - recognition (15) | 5 | 14.4 | 0.55 | 15 | 0.996 | 0.376 | 14.2 | 0.84 | 14 | -0.217 | 0.839 | 0.865 | 0.436 |

| Rey figure – copy (36) | 5 | 34.6 | 1.34 | 36 | 0.954 | 0.394 | 35 | 1 | 36 | 0.913 | 0.413 | 0.035 | 0.974 |

| Rey figure - delayed recall (36) | 5 | 25 | 5.84 | 26 | 0.156 | 0.883 | 22.8 | 6.9 | 27 | 0.556 | 0.608 | 0.71 | 0.517 |

| Letter fluency (FAS) | 5 | 49.8 | 13.5 | 65 | 1.028 | 0.362 | 51.4 | 14.05 | 64 | 0.819 | 0.459 | 0.515 | 0.634 |

| HADS – depression | 5 | 2.6 | 2.19 | 5 | 1.00 | 0.374 | 3.2 | 2.39 | 0 | -1.222 | 0.289 | 3.71 | 0.021 |

| HADS - anxiety | 5 | 6 | 3.39 | 3 | -0.808 | 0.464 | 5.4 | 3.78 | 7 | 0.386 | 0.719 | 1.582 | 0.189 |

NART = National Adult Reading Test; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; ASS = age scaled score; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

4.2.2. Experiment 1 - Word list recall

Verbal memory over time was explored using two word lists (“Animals” and “City”), each consisting of 16 category-related words (see Hoefeijzers et al., 2014), matched for word frequency (spoken and written), familiarity, imageability, concreteness and number of letters. Previous testing demonstrated their equivalence with respect to both learning over two trials and recall at the two delay intervals (Zeman et al., 2016). Both word lists had been administered in the 2013 assessment when CS was OFF baclofen.

Word List learning: Words were presented visually, one at time, via a 15-inch laptop screen (2s per word, 1s inter-item interval), with participants instructed to remember as many words as possible. After presentation of list 1 (“Animals”), an immediate recall test was administered followed by a 20-second backwards counting task. List 2 (“City”) was then presented, followed by an immediate recall trial of this list. This sequence was repeated, resulting in two learning trials per word list. Data were then collapsed across the two word lists to compute a mean recall score for each trial (max = 16). Learning rate was examined by taking the difference in recall from learning trial 1 to learning trial 2.

Word List Delayed recall (30-min and 1-week): Over a 30-minute period, participants then completed various tasks devoid of new meaningful verbal material, to minimise item-specific interference during subsequent word list retrieval. Participants were then asked to recall as many words as possible from each list. Participants were re-probed at 1-week within the same testing environment. They were not warned about the delayed memory tests. To control for individual differences and any between-group variation at immediate recall, retention scores were calculated for each participant, by dividing the number of words recalled at 30-minute and 1-week delayed recall by the number of words recalled at learning trial 2, and multiplying this quotient by 100.

Word List Recognition: Immediately following assessment of free recall at 1-week, participants were also assessed on their recognition memory using a 64-item yes/no test, comprising the 32 target words (“Animals” and “City”) and 32 foils (a mix of semantically-related, phonetically-related and unrelated words adapted from Hoefeijzers et al., 2015). Words were presented visually on a laptop screen. For each word, participants indicated verbally if it had been presented during the learning phase. Hit rates were calculated by dividing the number of targets correctly identified by the total number of targets (/32). False alarm rates were calculated by dividing the number of foils incorrectly identified as targets by the total number of foils (i.e. /32 when considering all foils; /12 for the analysis of phonologically-related foils; /10 for semantically related foils; and /10 for unrelated foils). In order to measure recognition accuracy, d-prime (d’) was calculated via the following equation: d’ = z(hit rate) – z(false alarm rate).

4.2.3. Experiment 2 - Visual recognition memory test

To investigate visual memory, participants were asked to remember and discriminate complex real-life photos depicting everyday scenes and activities (adapted from Dewar, Hoefeijzers, Zeman, Butler, & Della Sala, 2015). Familiar places, buildings or famous persons were avoided. Following the Huppert and Piercy approach (1978), 120 photographs were presented. From this original set, 40 pictures (i.e. targets) were probed at each of the two delay intervals, together with 40 foils (which included 20 photographs closely resembling 20 of the original photographs, but where aspects of the background or characters within the image were altered, and 20 unrelated photographs). After the 1-week delay test, an additional perception/visual short-term memory control test was also administered to confirm adequate perceptual and visual discrimination ability. A total of 70 complex colour photos were used in this test, matched to the recognition test images with regards to complexity, style and colour properties. This test comprised 45 trials.

The procedures were as follows:

Visual recognition - Picture presentation/encoding: Participants were informed that they would be shown a large number of pictures to remember, and that when tested for these later, they would also be shown additional pictures, some of which would be similar and others different to the target items. To ensure this was understood, participants were shown examples of both types of foils. Participants were explicitly asked to attend to and remember picture details in order to discriminate between identical and similar pictures during subsequent recognition testing. The 120 pictures were presented sequentially for 4 seconds on a 15-inch laptop screen.

Visual recognition - Memory testing: Following the encoding phase, participants completed filler tasks for 30 minutes, including the 30-minute delayed free recall test of the word lists from Experiment 1. When introducing the 30-minute and 1-week picture recognition tests, participants were reminded about the presence of identical, similar and different pictures in the test. Participants were then presented with 80 photographs. For each item presented, participants indicated verbally if they had seen that exact photograph during the study phase. Again, hit rates (/40), and d-prime (d’) were calculated by dividing the number of targets correctly identified by the total number of targets (/40). Overall false alarm rate was calculated by dividing the total false alarms by the number of all foils (/40), with separate calculations also provided when considering false alarm rates for similar foils (/20) and different foils (/20).

Perception/visual short-term memory control test: Immediately following the yes/no picture recognition test at 1-week, CS and controls were also administered the 45-item test to confirm the ability to perceive and discriminate complex photos and retain these within short-term memory. In each trial, a photograph was presented for 700ms, followed by a 900ms blank screen. The blank screen was followed directly by the presentation of a second picture, which could be the target picture seen 900ms before (x 20), a similar foil (x 20) or a different foil (x 5). Participants had to indicate verbally if the second picture was identical to the one they had been presented with before (yes/no response). Again, test performance was examined via hit rate, false alarm rate and d’, which we computed and analysed as described above.

4.2.4. Experiment 3: incidental story learning

To explore longer-term retention under more naturalistic conditions, an ‘incidental story’ test conducted in 2013 was repeated at the 2017 Retest (using the same material and procedure across both test sessions). Here, the experimenter told an apparently casual but well-rehearsed entertaining story about himself, which consisted of 51 story points (see Hoefeijzers, Zeman, Della Sala & Dewar, this issue). Retention was probed without warning a week later, first via free recall, followed by a 5-alternative forced-choice recognition test, consisting of 13 questions. To measure 1-week performance, the proportion of correct scores for both the free recall and 5-alternative forced-choice recognition tests was calculated.

4.2.5. Statistical analysis

CS’s 2013 and 2017 learning, 30-minute delayed recall and 1-week delayed recall scores on each of the 3 tasks were compared with those of the control group using Crawford’s modified t-tests for single case studies (singlims, Crawford & Garthwaite, 2002). To then compare CS’s change in performance from 2013 to 2017 with the change in performance over the equivalent time period in controls, we used Crawford’s RSDT modified t-tests (RSDT; Crawford & Garthwaite, 2005). All t-tests were two-tailed.

In cases where participants’ hit rate at recall intervals was equal to 1 (Word List task: n=1 control in 2013; Picture Recognition: n=2 controls in 2017) or their false alarm rate was 0 (Word List task: n=2 controls in 2013; Picture Recognition: n=2 controls in 2013 and 3 controls in 2017), corrections were made to allow for the computation of d’. In line with standard correction procedures, we corrected the hit score of 1 by subtracting half a hit (1/64 for Word Lists; 1/80 for Picture recognition) from this score, resulting in a corrected hit rate of .984 and .988 respectively on these two tasks. We corrected the false alarm score of 0 by adding half a false alarm to this score, i.e. (1/64 for Word Lists; 1/80 for Picture recognition), resulting in a corrected false alarm rate of 0.016 and 0.013 respectively.

5. Study 2 - Baclofen case report: ALF follow-up Results

5.1. Standard neuropsychological battery: CS vs controls

As in 2013, the 5 controls re-tested in 2017 were well matched to CS both demographically and on the majority of the standard tests (Table 2). The exception to this was in regards to CS’s significantly lower % retention score at the 30-minute delay interval of the WMS story recall task (78% retention vs the healthy control mean of 90%, t (4)= -3.075, p = .037). Despite this, her initial recall, delayed recall and recognition memory scores for this story all remained in keeping with her peers (all p> .184).

Comparing scores from 2013 and 2017, CS’s performance was stable and similar to controls for the majority of measures. Although the 2-point difference in her NART-predicted verbal IQ was statistically greater than changes observed in the control group (t(4) = 3.975, p = .016), there was no clinically meaningful change, with the result suggesting a stable, above average intellectual ability. On a task of verbal reasoning (WASI Similarities), her performance dropped from the superior range (age scaled score of 14) to within the normal range for her age (age scaled score of 11), while controls improved slightly (from an average age scaled score of 13.4 to 14.2; t(4) = 2.89, p = .045).

Other cognitive measures remained unchanged, and in keeping with stable performance over time in the control group. There was no indication of clinically significant anxiety or depression in either CS or the control group at either time point (although a statistically significant change was observed over time for CS versus controls - in 2017 she no longer endorsed any symptoms while her matched peers on average continued to report a small number: mean of 3.2; t(4) = 3.71, p = .021).

On clinical interview, CS reported that her memory for events of recent weeks and months now seemed similar to that of her friends and family, in marked contrast to the period when she was taking high dose baclofen. Despite this improvement, she felt that clear ‘gaps’ remained in her ability to recall remote, salient autobiographical events that she would have expected to remember. She has now returned to an active life, with a busy schedule of social and cultural events and demanding voluntary work. In this role she is able to use her skills as an accountant, her role prior to her spinal injury in 2009.

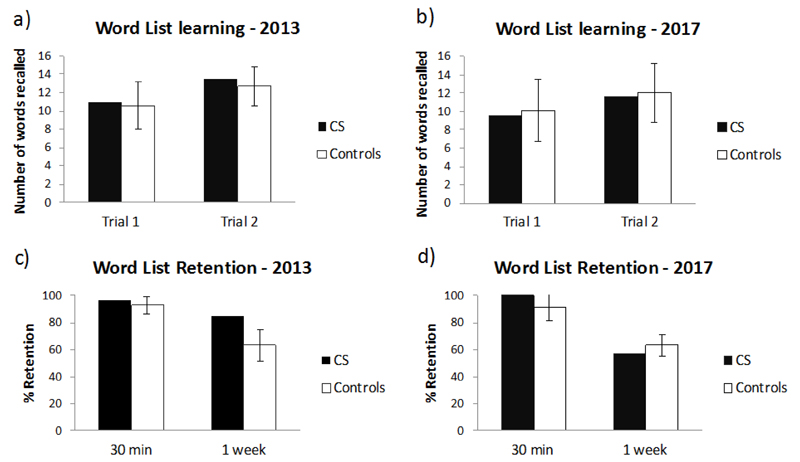

5.2. Experiment 1: Word list recall and recognition

5.2.1. Word list recall

CS’s immediate recall, learning rate (over 2 trials) and percentage retention at both the 30-min and 1-week free recall test, were comparable to those of the controls, both when tested in 2013 (OFF baclofen; all p > .17) and at the retest 4 years later once withdrawn completely from this drug (all p > .46; see Figure 3 and Suppl. Table 4a). At both time points, ALF was not observed in CS, relative to the controls (i.e. CS’s forgetting rate over the 30-min to 1-week delay interval was not significantly different from the 5 controls, 2013: t(4) = 0.955, p = .394; 2017: t(4) = 0.979, p = .383). Although some drop in CS’s performance between 2013 and 2017 at 1-week was noted, this was not statistically different from the change over time observed by the 5 controls (t(4) = 1.555 ; p =.195).

Figure 3.

Word list recall test: mean number of words recalled at learning trials 1 and 2 (a, b), and percentage word retention after 30 min and 1 week (c, d) during 2013 and 2017 in CS and in 5 controls. Bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. No significant differences are found between CS and controls for any of the comparisons (all p >.12).

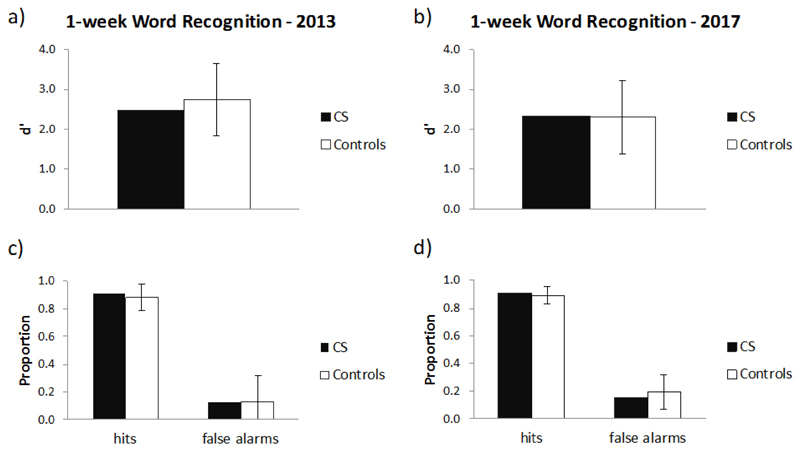

5.2.2. Word list recognition

Comparable results between CS and controls were also found on the word list recognition test (Figure 4), with no differences in d’, Hit rate or False alarm rate between CS and controls at either time point (all p > .79), and no difference between CS and the controls in the change from 2013 to 2017 on these measures (all p > .69; Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 4.

Word list recognition: 1-week recognition performance during 2013 and 2017 in CS and in 5 controls. d' (a, b), and hit rate and false alarm rate (c, d). Bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation. No significant differences are found between CS and controls for any of the comparisons (all p >.69).

Recognition performance was also analysed separately for phonologically-related foils, semantically-related foils and unrelated foils. There was no significant difference between CS’s false alarm rate and that of controls for any foil type in 2013 or in 2017 (all p > .413). Moreover, when comparing CS with controls there was no significant difference in the degree of change from 2013 to 2017 in false alarm rate for any foil type (see Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 5).

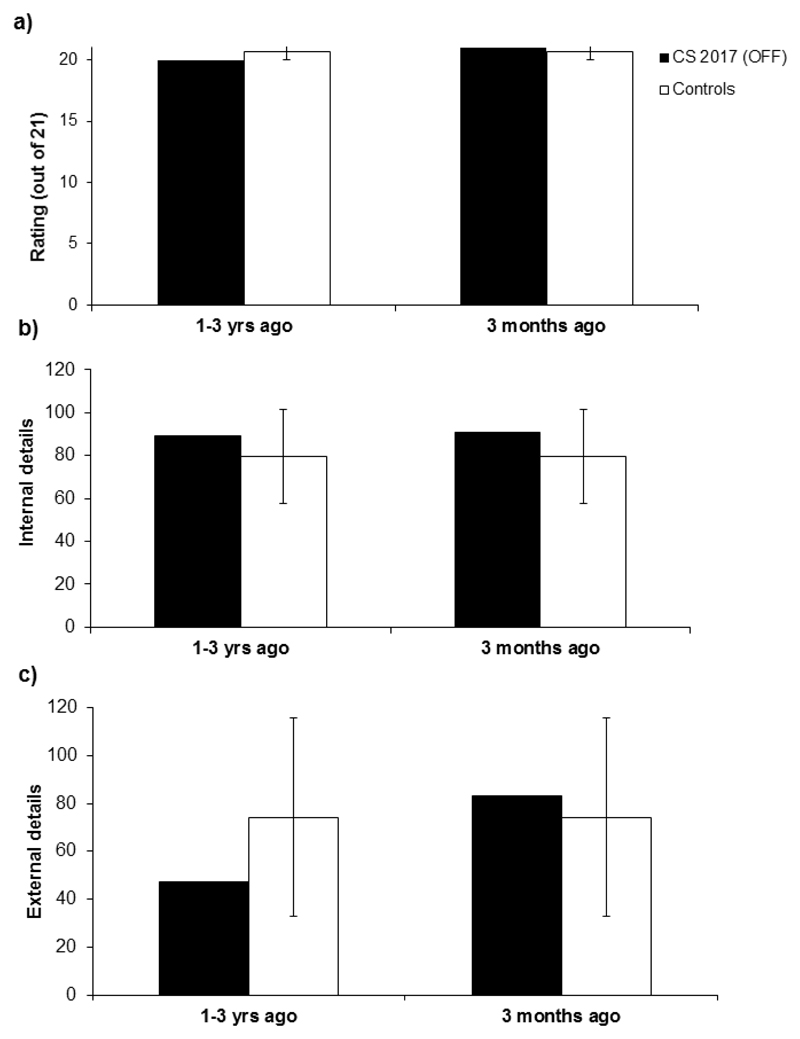

5.2.3. Experiment 2: visual recognition memory (pictures)

When assessed on visual material, CS’s performance continued to show no differences with matched controls, in relation to d’, Hit rate and False alarm rate on the picture at the two time points (all p > 0.12, Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 6). The drop in recognition scores (d’, Hit rate and False alarm rate) between the 30-minute and the 1-week delay interval was also not significantly different between CS and the control group when measured both in 2013 (all p > .2) and 2017 (all p > .1).

Figure 5.

Picture recognition: 30-min and 1-week picture recognition performance during 2013 and 2017 in CS and 5 controls. d' (a, b), hit rate (c, d), and false alarm rate (e, f). Bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation.

Interestingly, however, CS’s change in performance between 2013 and 2017 on the Hit rate (at both the 30-minute and 1-week test delay) and False alarm rate (at the 1-week test delay) was significantly different to that of the controls (Hit rate 30-minute delay: t = 4.815, p = .009; Hit rate 1-week delay: t = 2.841, p = 0.047; False alarm rate 1 week delay: 4.706 ; p = 0.009, see Supplementary Table 3). More specifically, CS’s performance in 2017 was more conservative than her performance 4 years earlier, shown in Figure 5c and 5e by the decrease in both CS’s hit rate (at both the 30-minute and 1-week test delay) and false alarm rate (at the 1-week test delay) when comparing 2017 versus 2013. This change in behaviour was not observed in the Control group, who continued to show similar rates across time (see Figure 5d and 5f).

Recognition performance was also analysed separately for similar foils and different foils. There was no significant difference between CS’s false alarm rate and that of controls for either foil type when tested in 2013 or in 2017 (all p >.1), when measured both at the 30-minute and the 1-week delay (see Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 6). When examined over time, however, CS showed a relative reduction in false alarms for ‘different’ foils at the 1-week picture recognition test compared with controls (p = 0.016). This drop in false alarms from 2013 to 2017 is at first suggestive of an improvement in CS’s ability to distinguish irrelevant pictures (different foils) from pictures with previously seen features (i.e. originally presented pictures and similar foils). However, as there was also a corresponding significant drop in CS’s hit rate (p=0.047), this may simply reflect a more conservative approach to responding overall (i.e. resulting in fewer “yes” decisions across both hits and false alarms), as noted in the preceding paragraph.

Her performance on the perception/visual short-term memory control test indicated that CS had no difficulties in discriminating between perceptually similar photos after a 900-ms delay, either during the 2013 or 2017 assessments (2013 d’: CS = 3.920, control mean = 3.920 (SD = .000), t(4) = .000, p = 1.000; 2017 d’: CS = 3.605 control mean = 3.857 (SD = .141), t(4) = -1.632, p = .178).

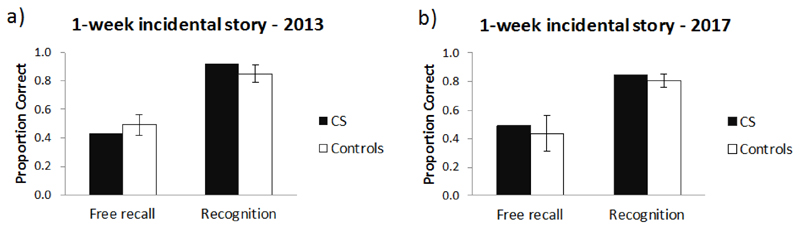

5.2.4. Experiment 3: Incidental story recall

CS’s 1-week free recall and multiple-choice recognition performance on an “incidental story” was comparable to that of the control group, both in 2013 and in the 2017 follow-up. CS’s change in performance over this 4 year time period was not significantly different to that of the controls for either free recall or multiple-choice recognition (see Supplementary Table 7).

It is of note that at the 1-week delay interval (both in 2013 and 2017), all controls remembered having heard the story back in 2012. As a result, they were aware that recall of this “spontaneously” told story would be tested later on. In contrast, during storytelling in 2013, CS had no recollection of having heard the story previously but did recall it during the 2017 session.

6. Study 2 - Baclofen case report: Autobiographical Memory Follow-up

6.1. Materials and Methods

We investigated CS’s memory for new autobiographical events using the Autobiographical Interview (AI; Levine, Svoboda, Hay, Winocur, & Moscovitch, 2002), which is arguably the most sensitive measure of autobiographical memory performance currently available. The AI involves 3 phases: a recall stage where participants are asked to recollect as much information as they can about a particular event, a general probe consisting of non-specific questions (e.g., “can you provide more details?”) and a specific probe where participants are asked more specific questions in a semi-structured interview in order to extract as much contextual detail as possible. The specific probe is administered after completing the free recall and general probe phases for each memory.

CS was asked to retrieve two memories: the first for an event which occurred less than one year ago, but more than 3 months ago, and the second relating to an event from 1 to 3 years ago. This allowed us to examine CS’s ability to retain new autobiographical memories encoded after having withdrawn from baclofen, addressing the previous gap in our assessment of her memory (Zeman et al., 2016).

The memories were audio-recorded, transcribed and scored using standard procedures (Levine et al., 2002). Specifically, narratives were segmented into details classified as ‘internal’ or ‘external’ (Levine et al., 2002). Internal details were episodic information specific to the selected event which can be subdivided into event, perceptual, time, place, and emotion/thought details. External details included information extrinsic to the event and consisted of semantic (factual information or extended events) and ‘other’ (e.g. metacognitive statements, editorializing and inferences) details. Contextual information that was not part of the chosen episode was also classified as external detail. Repetitions were scored but not included as either internal or external details. (c.f., Milton et al., 2010).

Additionally, qualitative ratings were assigned to each memory (Levine et al., 2002). The time, place, perceptual, and emotion/thought sub-categories were rated on a scale from 0 (no information relating to that sub-category) to 3 (specific, rich detail pertaining to the sub-category). Episodic richness was scored on a 0–6 scale to account for its greater importance. A time integration measure (on a 0–3 scale) assessed the integration of the episode into a larger time scale. The ratings summed to 21. CS’s scores were compared to a recent memory obtained from 12 healthy, age and IQ matched control participants whom we have previously reported (Milton et al., 2010). These memories were matched for age to the memories recalled by CS. The interviews were all analysed by one scorer for consistency. A second scorer analysed a subset of the memories (˜20%). Both scorers had undergone extensive training with the scoring methods laid out by Levine et al. (2002). Coefficients showed extremely close agreement across all measures (> .90).We used Crawford’s modified t-tests (as described in 4.2.5) to analyse data.

6.2. Autobiographical Memory Follow-up

The total internal and external details recalled by CS, together with the qualitative ratings for both memories as compared with the mean scores for the control group are shown in Figure 7. For the memory less than 1 year ago, there was no difference between CS and the controls in the number of internal details, t(12) = .497, p = .629, external details, (12) = .205, p = .842, or in the qualitative rating t (12) = .487, p = .636. The same pattern emerged for the memory from 1-3 years ago for the internal details, t(12) = .410, p = .690, external details, t(12) = -.630, p = .542, or qualitative rating, t(12) = -.989, p = .344. Taken together these results suggest that CS no longer has detectable problems retaining everyday memories over months/years now that she is off baclofen.

Figure 7.

a) Memory quality, b) Number of internal details, and c) Number of external details for CS’s recent memories compared to 12 age- and IQ-matched control participants. Error bars indicate one standard deviation.

7. Discussion

ALF is a common neuropsychological concomitant of TEA, typically affecting around half of cases (Butler et al., 2007). Although previous studies of TLE have suggested that ALF may be treatable (e.g. following surgery for those with intractable seizures, Evans et al., 2014), the long-term outcome of ALF in patients who cease having seizures in response to medication is unknown. In TEA, seizure cessation with anti-convulsants occurs in over 90% of cases at the time of presentation (Butler et al., 2007; Mosbah et al., 2014). Short-term follow up of single cases suggest improvements in memory functioning. If seizure activity is a key determinant of ALF in epilepsy, then we might expect to see a reduction in ALF over time in successfully treated TEA patients.

Here we provide the first group study of TEA patients where this has been examined. Patients were tested 10 years apart to investigate the long-term stability of ALF. To complement this investigation of ALF over time, we also present an additional case in which ALF remitted for a reason that we understand (dose related, baclofen-induced ALF) and memory performance was measured over a 4-year period.

When followed up after 10 years, the majority of TEA patients reported few if any seizures since T1; only 3 (21%) participants had experienced multiple seizures which required a review of their medication. In each case, this had occurred only within the previous 1-2 years. While their memory scores are reported within the group results, additional analyses of individual performances allow us to consider the impact of these individuals on the group outcomes.

Results indicated, at a group level, a stable pattern of TEA patients demonstrating greater forgetting of new information over a 1-week period of recall compared with matched healthy controls, with no indication of further decline over the 10-year period. By contrast, at an individual level, consistent with the hypothesis regarding seizure activity and ALF in epilepsy, ALF was no longer evident in 4 of the 7 TEA patients who initially reported ALF. In 3 of these cases, ALF had been demonstrated on experimental measures at T1, but when repeated 10-years later was no longer present, following successful treatment of seizures. In the remaining “ALF improver”, infrequent (1-2/yr) seizures were still occurring. For participants where seizures had initially ceased but then re-emerged in recent years, ALF either remained present and stable, or in one case (a man who had multiple seizures), worsened.

These results occurred within the context of stability in intellectual function and executive function. Some decline, however, was evident in initial encoding and learning of new information, with significant group differences in standard neuropsychological tasks of verbal memory (story recall).

Whilst self-report measures should always be taken with some caution they provide a valuable insight into the perceived memory problems that patients with TEA experience. These showed that TEA participants continued to endorse a similar level of concern regarding everyday memory failures as they had at T1, although the perceived difficulties with remote memory had lessened over time.

ABM performance remained below control levels, although over time this disparity between groups had lessened (with a trend towards significant improvement in episodic recall when examining the most recent decade). At an individual level, ABM for episodic details of recent memory (i.e. for events after successful use of anti-convulsant medication), improved for those individuals who no longer experienced ALF or reported seizures.

Likewise, in a case of remitted ALF originally induced by high doses of baclofen, ABM for memories which were encoded after ALF had resolved, was restored to normal performance. We discuss the key findings in turn.

7.1. ALF in the context of long-term cognitive profile

At a group level, TEA participants continued to show ALF compared with healthy controls, evident on the story recall and memory for designs tasks. This was set in the context of stable, above average general intellectual ability. Likewise, patients with TEA remained in keeping with their peers for the majority of cognitive domains, with normal language (naming), visuospatial function (drawing), and executive skills (problem solving and reasoning ability). This pattern of stability is reassuring and helps to counter concerns recently raised regarding possible vulnerability of TEA in subsequently developing Alzheimer’s Disease (Cretin et al., 2014), and is consistent with findings in a smaller cohort of 10 patients followed up over a 20-year period (Savage, Butler, Hodges, & Zeman, 2016).

Within the broader domain of memory, however, different patterns emerged. Most notably, reductions in the initial encoding and subsequent recall of a short story were evident for the group. This was consistent with the fact that several participants failed to meet learning criteria for the ALF tasks, despite up to 15 repetitions. Performance on recognition memory was also reduced, including poorer performances on average for the recognition test from the Warrington words and faces tasks. There was also an impairment in recognising famous faces. Difficulty with memory for faces has been reported previously in case studies of TEA (Kapur, 1993; Kapur et al., 1989) and was seen in the smaller follow up study (Savage et al., 2016). The suggestion of a slowly declining memory has been proposed in other forms of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy, wherein patients continue to perform below average levels, but do not show a pattern of decline which is suggestive of dementia (Helmstaedter & Elger, 2009). By contrast, visual recall (RCFT) appeared to remain stable and within the normal range. Thus not all aspects of memory were seen to decline.

At an individual level, although intellectual ability remained above average for all participants, greater variability in memory outcome was evident. Encouragingly, 6 out of the 10 individuals reporting ALF at T1 no longer showed signs of this when formally tested at T2 (4 who had been tested at both time points, and 2 who had not been tested at T1 but had provided subjective reports of ALF). In addition, positive outcomes were also apparent in relation to other aspects of memory. While declines were observed at a group level, a proportion of patients (ranging from 8-38% depending upon the measure) either produced the same or a higher score than at T1. Given some reductions in numeric score may be anticipated over a 10-year ageing period, this stability increase in score is also encouraging.

While the sample did not include many without reports of ALF at T1, there was no indication of ALF newly developing over time (thus suggesting it may not be something which develops later for those who are symptom-free initially).

In our baclofen-induced ALF case, CS, no ALF was observed, in keeping with her withdrawal from the drug over the 4-year period. As with the TEA group, CS’s overall cognitive profile remained above average over the follow-up period. A drop was noticed in her recall of the WMS story, although her visual recall remained excellent.

7.2. Relationship between seizure control and memory performance

Consistent with the hypothesis that reduced seizure activity would result in memory improvements, the majority of individuals who experienced positive outcomes had also been seizure-free (or at most experienced a couple of seizures within the 10-year period). This applied both to the ALF measures (4 of the 6 ‘ALF improvers’) and on the standard neuropsychological tests of memory. Conversely, for TEA patients where seizures had initially ceased but then re-emerged in recent years, ALF either remained present and stable, or in one case (a man who had multiple seizures), worsened. Participant 114 who was never medicated, and continues to experience infrequent episodes annually, showed good recall over the 1-week testing interval, but did not always demonstrate good initial learning. While these numbers are of course very small, a somewhat consistent pattern emerges where seizures cessation appears linked with improvements and re-emergence of seizures is linked with memory declines.