Abstract

Previous prospective studies assessing the relationship between circulating concentrations of vitamin D and prostate cancer risk have shown inconclusive results, particularly for risk of aggressive disease. In this study, we examine the association between pre-diagnostic concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and 1,25(OH)2D and the risk of prostate cancer overall and by tumor characteristics. Principal investigators of 19 prospective studies provided individual participant data on circulating 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D for up to 13,462 men with incident prostate cancer and 20,261 control participants. Odds ratios (OR) for prostate cancer by study-specific fifths of season-standardized vitamin D concentration were estimated using multivariable-adjusted conditional logistic regression. 25(OH)D concentration was positively associated with risk for total prostate cancer (multivariable-adjusted OR comparing highest versus lowest study-specific fifth was 1.22, 95% CI 1.13-1.31; P trend<0.001). However, this association varied by disease aggressiveness (Pheterogeneity=0.014); higher circulating 25(OH)D was associated with a higher risk of non-aggressive disease (OR per 80 percentile increase=1.24, 1.13-1.36) but not with aggressive disease (defined as stage 4, metastases, or prostate cancer death, 0.95, 0.78-1.15). 1,25(OH)2D concentration was not associated with risk for prostate cancer overall or by tumor characteristics. The absence of an association of vitamin D with aggressive disease does not support the hypothesis that vitamin D deficiency increases prostate cancer risk. Rather, the association of high circulating 25(OH)D concentration with a higher risk of non-aggressive prostate cancer may be influenced by detection bias.

Keywords: prostate cancer; vitamin D; 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; pooled analysis

Introduction

It has been hypothesized that vitamin D deficiency may increase prostate cancer risk (1,2). A meta-analysis of 6 prospective studies published up to 2010 reported that circulating vitamin D concentrations were not related to prostate cancer risk (3); however, it was insufficiently powered to provide robust estimates of risk, especially for important disease subgroups. While the active hormonal form of vitamin D is 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), which is mainly formed by hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in the kidney under the control of parathyroid hormone, circulating 25(OH)D concentration is regarded as the most informative indicator of vitamin D status.

The Endogenous Hormones, Nutritional Biomarkers and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group (EHNBPCCG) was established to conduct collaborative reanalyzes of individual data from prospective studies on the relationships of circulating hormone concentrations and nutritional biomarkers with prostate cancer risk (4,5). With pooled individual participant data on pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations from 19 prospective studies (with up to 13,462 men with incident prostate cancer), this analysis aimed to provide precise estimates of the association of circulating vitamin D with prostate cancer risk and to investigate whether these associations differed by tumor characteristics or time from blood collection to diagnosis. We also examined the cross-sectional relationships between lifestyle factors and vitamin D concentrations.

Material and methods

Data collection

Published and unpublished studies were eligible for the current analysis if they had data on pre-diagnostic circulating concentrations of 25(OH)D or 1,25(OH)2D and incident prostate cancers. Studies were identified using literature search methods from computerized bibliographic systems and by discussion with collaborators, as described previously (4,5). Data were available for 19 prospective studies by dataset closure in May 2018.

Individual participant data were requested on circulating 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D, date, age and fasting status at sample collection, marital status, ethnicity, educational attainment, family history of prostate cancer, height, weight, waist and hip circumference, smoking status, alcohol intake, and vital status. Each study also provided data on prostate cancer stage and grade and death, if available, and the data were harmonized in a central database. Further details on data collection and processing are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Study designs and data processing

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and details of the assay methods are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Most of the studies were case-control studies nested within prospective cohort studies. Data on the control participants from The Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial are included in cross-sectional analyses of vitamin D concentrations in relation to participant characteristics, but because cases were diagnosed at the start of the study rather than during follow-up, these data were not included in the main risk analyses. Written informed consent was obtained from study participants at entry into each cohort or was implied by participants’ return of the enrolment questionnaire. The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards of each study center.

Prostate cancer was defined as being ‘early’ stage if it was tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage T1 with no reported lymph node involvement or metastases, or stage I; ‘other localized’ stage if it was TNM stage T2 with no reported lymph node involvement or metastases, stage II, or the equivalent; ‘advanced’ stage if it was TNM stage T3 or T4 and/or N1+ and/or M1, stage III–IV, or the equivalent; or stage unknown. Aggressive disease was categorized as “no” for TNM stage T0, T1, T2 or T3 with no reported lymph node involvement and no metastases or equivalent, “yes” for TNM stage T4 and/or N1+ and/or M1 and/or stage IV disease and/or death from prostate cancer, or “unknown”. Histological grade was defined as ‘low-intermediate’ if the Gleason sum was < 8 or equivalent, ‘high’ grade if the Gleason sum was ≥ 8 or equivalent, or grade “unknown”. Fatal cases were men who died of prostate cancer during follow-up.

Statistical analyses

25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations were log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution for parametric analyses. To allow for the influence of month of blood draw on circulating concentrations, a regression model of log-transformed vitamin D concentration by month of blood collection was fitted for each study. All results are presented by season-standardized vitamin D, unless otherwise specified.

The main method of analysis was logistic regression conditioned on the matching variables within each study. Men were categorized into fifths of the distribution of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D, with cut-points defined by the study-specific quintiles of the distribution within control participants, to allow for any systematic differences between the studies in assay methods and blood sample types (6). Linear trends were calculated by replacing the categorical variable representing the fifths of each analyte with a continuous variable that was scored as 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1; a unit increase in this variable can be taken to represent an 80 percentile increase in the study-specific concentration of vitamin D. To examine the effects of potential confounders (other than the matching criteria, which were taken into account in the study design and matched analyses), conditional logistic regression analyses included the following covariates: age at blood collection, body mass index (BMI), height, marital status, educational status, and cigarette smoking, all of which were associated with prostate cancer risk in these analyses.

In a sensitivity analysis, conditional logistic regression models were also fitted using quintile cut-points defined by the overall distribution among the control participants in all studies combined. The analyses were also repeated using predefined categories for concentrations of 25(OH)D of <30, 30-<50, 50-<75 and ≥75 nmol/L, in order to investigate risks associated with very low (deficiency), low (insufficiency), moderate (sufficiency) and high circulating concentrations of vitamin D based on the Institute of Medicine recommendations (7).

For each analyte, heterogeneity in linear trends between studies was assessed by comparing the χ2 values for models with and without a (study) x (linear trend) interaction term. Tests for heterogeneity for the case-defined factors were obtained by fitting separate models for each subgroup and assuming independence of the ORs using a method analogous to a meta-analysis, in which controls in each matched set were assigned to the category of their matched case. Tests for heterogeneity for non-case defined factors were assessed with χ2 tests of interaction between subgroups and the binary variable.

In order to assess potential effect modification with different biomarkers, a χ2 test of interaction was used to determine whether risks by study-specific thirds of 25(OH)D varied according to study-specific thirds of 1,25(OH)2D (and vice versa), and according to study-specific thirds of circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP3), testosterone, free testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA), where these data were available.

The cross-sectional associations of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D with participant characteristics (among controls only) were examined using analyses of variance to calculate geometric mean concentrations and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for study and age at blood collection, as appropriate.

All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at the 5% level. All statistical tests were carried out with Stata Statistical Software, Release 14 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Texas). Full details of the statistical analyses are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

Details of the 19 participating studies are shown in Table 1. Data on 25(OH)D concentrations were available for 13,462 men who subsequently developed prostate cancer and 20,261 control participants, and for 1,25(OH)2D concentrations for 1,885 case and 2,114 control participants. Mean age at blood collection across the studies ranged from 46.5 (SD = 4.2) to 76.3 (3.6) years. Blood collection preceded prostate cancer diagnosis by an average of 8.5 years (SD = 6.0 years), although there was a wide variation among the studies (Table 2). On average, cases were 67.5 years old (SD = 7.3 years) at diagnosis and most (87.1%) were diagnosed after 1994. The majority of cases with information on stage and grade of disease had localized (early or other localized) disease (ranging from 47.8% to 99.0% of case patients across studies) and low-intermediate grade tumors (ranging from 75.8% to 100% of case patients). Concentrations of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D varied significantly by month among both the cases and controls (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1. Participant characteristics by study and case-control statusa.

| Prospective studies (First author, year) | Case-control status | Number | Age at recruitment (y) | BMI (kg/m2) | Married or cohabiting (%)b | Higher education (%)b | Current smoker (%)b | Intake of alcohol (g/d) | Family history of prostate cancer (%)b | Geometric mean

concentration (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25(OH)Dc (nmol/L) |

1,25(OH)2Dc (pmol/L) |

||||||||||

| ARIC (Unpublished)d | Case | 700 | 55.4 (5.7) | 27.5 (4.0) | 88.3 | 17.9 | 20.6 | 9.1 (15.9) | 13.3 | 60.1 (58.6-61.7) | - |

| Control | 2752 | 55.2 (5.7) | 27.5 (4.2) | 85.8 | 11.6 | 26.9 | 9.9 (18.3) | 6.2 | 59.7 (58.8-60.5) | - | |

| ATBC (Albanes et al., 2011) | Case | 996 | 58.4 (5.2) | 26.3 (3.6) | 82.5 | 6.1 | 100 | 17.3 (23.2) | 7.3 | 32.6 (31.4-33.8) | - |

| Control | 996 | 58.4 (5.1) | 26.1 (3.7) | 81.4 | 4.3 | 100 | 15.4 (19.5) | 3.5 | 31.4 (30.2-32.6) | - | |

| CLUE 1 (Braun et al., 1995) | Case | 61 | 58.3 (8.5) | - | 91.8 | 11.5 | 29.5 | - | - | 82.1 (76.3-88.2) | 94 (87-102) |

| Control | 122 | 58.3 (8.5) | - | 86.9 | 9.8 | 25.4 | - | - | 79.0 (74.7-83.4) | 91 (85-97) | |

| EPIC (Travis et al., 2010) | Case | 652 | 60.4 (6.3) | 26.7 (3.4) | 88.8 | 24.9 | 20.3 | 19.1 (23.9) | - | 53.8 (52.3-55.3) | - |

| Control | 752 | 59.9 (6.3) | 26.8 (3.5) | 88.6 | 19.8 | 22.6 | 17.0 (19.9) | - | 53.2 (51.8-54.7) | - | |

| ESTHER (Ordonez-Mena et al., 2013) | Case | 216 | 64.3 (5.1) | 27.3 (3.1) | 83.9 | - | 13.9 | 16.6 (19.7) | 5.1 | 55.3 (51.7-59.1) | - |

| Control | 841 | 64.3 (5.1) | 28.0 (4.2) | 84.6 | - | 14.6 | 14.2 (15.3) | 3.8 | 54.2 (52.6-55.8) | - | |

| FMC (Unpublished)d | Case | 161 | 57.9 (10.4) | 25.8 (3.1) | 90.6 | - | 29.0 | - | - | 51.5 (47.6-55.6) | - |

| Control | 286 | 57.2 (10.4) | 26.1 (3.6) | 85.0 | - | 34.9 | - | - | 50.4 (47.8-53.0) | - | |

| HIMS (Wong et al., 2014) | Case | 332 | 76.4 (3.7) | 26.4 (3.5) | 86.7 | 22.9 | 4.5 | 11.7 (15.5) | - | 66.8 (64.5-69.2) | - |

| Control | 1317 | 76.3 (3.6) | 26.5 (3.7) | 86.2 | 21.7 | 4.6 | 11.8 (16.1) | - | 64.3 (63.1-65.5) | - | |

| HPFS (Platz et al., 2004; Mikkah et al., 2007; Shui et al., 2012) | Case | 1326 | 63.8 (7.8) | 26.0 (3.3) | 92.7 | 100 | 4.4 | 11.8 (15.4) | 14.4 | 68.1 (66.5-69.7) | 83 (81-86) |

| Control | 1326 | 63.7 (7.8) | 26.1 (3.5) | 93.0 | 100 | 3.5 | 11.6 (15.8) | 10.6 | 66.2 (64.4-68.0) | 83 (81-85) | |

| Janus part 1 (Tuohimaa et al., 2004) | Case | 575 | 46.5 (4.3) | 25.4 (3.1) | - | - | 60.6 | - | - | 52.1 (50.6-53.7) | - |

| Control | 2233 | 46.5 (4.2) | 25.1 (3.2) | - | - | 62.3 | - | - | 49.7 (49.0-50.4) | - | |

| Janus part 2 (Meyer et al., 2013) | Case | 2106 | 47.7 (9.2) | 25.5 (3.0) | - | - | 32.8 | - | - | 60.4 (59.6-61.3) | - |

| Control | 2106 | 47.7 (9.2) | 25.6 (3.0) | - | - | 34.5 | - | - | 58.7 (57.9-59.6) | - | |

| JPHC (Sawada et al., 2017) | Case | 201 | 59.5 (6.4) | 23.4 (2.4) | 100 | - | 34.3 | 26.9 (31.7) | 0.5 | 86.9 (82.7-91.3) | - |

| Control | 402 | 59.2 (6.6) | 23.3 (2.6) | 100 | - | 40.8 | 31.6 (47.6) | 0.0 | 85.6 (82.7-88.6) | - | |

| MCCS (Unpublished)d | Case | 818 | 58.4 (7.4) | 27.1 (3.4) | 82.7 | 30.7 | 8.3 | 17.9 (22.8) | - | 52.5 (51.3-53.8) | - |

| Control | 1151 | 56.4 (7.7) | 26.9 (3.4) | 78.2 | 26.9 | 12.9 | 17.8 (23.9) | - | 50.2 (49.1-51.2) | - | |

| MDCS (Brandstedt et al., 2012) | Case | 910 | 61.3 (6.4) | 26.3 (3.3) | 77.8 | 14.6 | 22.2 | 14.9 (14.6) | - | 83.4 (81.8-85.0) | - |

| Control | 910 | 61.1 (6.4) | 26.1 (3.3) | 75.7 | 12.6 | 26.7 | 14.6 (14.2) | - | 82.0 (80.4-83.6) | - | |

| MEC (Park et al., 2010) | Case | 329 | 68.9 (7.1) | 26.6 (4.0) | 77.1 | 34.0 | 14.1 | 23.3 (44.1) | 13.9 | 77.6 (74.2-81.2) | - |

| Control | 656 | 68.7 (7.2) | 26.8 (4.0) | 78.6 | 32.9 | 12.6 | 22.5 (39.1) | 8.8 | 75.6 (73.2-78.0) | - | |

| PCPT (Schenk et al., 2014) | Case | 915 | 63.3 (5.5) | 27.5 (4.2) | 87.5 | 38.5 | 6.7 | 9.6 (15.8) | 21.7 | 58.6 (57.2-60.0) | - |

| Control | 915 | 63.3 (5.5) | 27.6 (4.0) | 87.2 | 37.7 | 6.8 | 8.9 (13.7) | 21.6 | 56.0 (54.7-57.4) | - | |

| PHS (Gann et al., 1996; Ma et al., 1998; Li et al., 2007) | Case | 501 | 58.6 (7.6) | 24.6 (2.5) | - | 100 | 7.8 | 7.2 (6.0) | - | 72.6 (70.3-75.0) | 79 (77-80) |

| Control | 669 | 59.1 (7.6) | 24.6 (2.5) | - | 100 | 7.0 | 7.1 (6.3) | - | 71.3 (69.3-73.3) | 79 (77-80) | |

| PLCO (Ahn et al., 2008) | Case | 747 | 64.8 (5.0) | 27.3 (3.6) | 88.0 | 43.3 | 6.4 | 15.7 (29.5) | 12.3 | 56.1 (54.8-57.4) | - |

| Control | 727 | 64.5 (4.9) | 27.6 (3.9) | 85.8 | 39.5 | 9.8 | 16.2 (30.1) | 5.2 | 54.0 (52.7-55.4) | - | |

| SELECT (Kristal et al., 2014) | Case | 1732 | 63.5 (6.1) | 28.5 (4.3) | 84.1 | 54.9 | 5.4 | 9.4 (15.7) | 31.2 | 64.9 (63.6-66.3) | - |

| Control | 1732 | 63.6 (6.4) | 28.7 (4.7) | 82.6 | 51.0 | 7.1 | 9.2 (20.0) | 15.3 | 63.8 (62.5-65.2) | - | |

| SU.VI.MAX (Deschasaux et al., 2016) | Case | 184 | 54.1 (4.8) | 25.5 (3.1) | 93.3 | 30.2 | 11.1 | 25.1 (19.2) | 12.7 | 44.1 (41.2-47.2) | - |

| Control | 368 | 53.8 (4.4) | 25.7 (3.2) | 89.3 | 26.8 | 12.8 | 25.5 (18.9) | 4.4 | 45.9 (43.7-48.2) | - | |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Numbers are for men with a 25(OH)D measurement and in complete matched case-control sets.

Percentages exclude men with missing values.

25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)D concentrations are season-standardised.

Unpublished vitamin D and prostate cancer data, Study references: Joshu et al., 2018 for ARIC, Knekt et al., 2008 for FMC and Milne et al., 2017 for MCCS

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study; BMI, body mass index; CLUE, Campaign Against Cancer and Stroke (“Give Us a Clue to Cancer”) Study; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; FMC, Finnish Mobile Clinic Health Examination Survey; HIMS, Health in Men Study; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; Janus part 1, Nordic Biological Specimen Biobank Working Group; Janus part 2, a second study using the Janus Serum Bank from Norway; JPHC, Japan Public Health Cohort; MCCS, Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study; MDCS, Malmö Diet and Cancer Study; MEC, Multiethnic Cohort; N/A, data not available for this study; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PHS, Physicians Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SELECT, Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial; SU.VI.MAX, Supplémentation en Vitamines et Minéraux Antioxydants; 25(OH)D,25-hydroxyvitamin D ; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants with prostate cancera.

| Prospective studies | Time from blood collection to diagnosis (%)a | Age at diagnosis (%)a | Year of diagnosis (%)a | Disease stage, aggressiveness and grade (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 y | 3-6 y | ≥7 y | <60 y | 60-69 y | ≥70 y | Before 1990 | 1990-1994 | 1995-Onward | Advanced stageb | Unknown stage | Aggressive diseaseb | High gradeb | Unknown grade | |

| ARIC | 3.6 | 13.1 | 83.3 | 9.7 | 48.9 | 41.4 | 1.1 | 12.4 | 86.4 | 16.6 | 21.6 | 10.9 | - | 15.0 |

| ATBC | 4.0 | 10.6 | 85.3 | 3.5 | 44.4 | 52.1 | 5.3 | 15.2 | 79.5 | 52.2 | 19.3 | 39.1 | 11.8 | 21.5 |

| CLUE I | 0.0 | 1.6 | 98.4 | 8.2 | 23.0 | 68.9 | 59.0 | 41.0 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 16.4 | 37.7 | 5.1 | 3.3 |

| EPIC | 33.1 | 50.9 | 16.0 | 17.2 | 62.6 | 20.3 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 99.2 | 26.2 | 28.7 | 21.3 | 10.4 | 16.1 |

| ESTHER | 24.1 | 38.4 | 37.5 | 2.3 | 44.0 | 53.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | - | 100 | 11.6 | - | 100 |

| FMC | 6.2 | 16.8 | 77.0 | 10.6 | 34.2 | 55.3 | 87.0 | 13.0 | 0.0 | - | 100 | 42.2 | - | 100 |

| HIMS | 42.2 | 45.8 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | - | 100 | 11.5 | - | 100 |

| HPFS | 23.9 | 42.8 | 33.3 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 94.0 | 4.3 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 11.2 |

| Janus part 1 | 1.2 | 5.0 | 93.7 | 20.7 | 69.2 | 10.1 | 27.0 | 56.2 | 16.9 | - | 100 | - | - | 100 |

| Janus part 2 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 93.7 | 40.6 | 32.1 | 27.3 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 93.4 | 27.7 | 29.4 | 22.8 | - | 100 |

| JPHC | 9.0 | 17.4 | 73.6 | 7.0 | 39.8 | 53.2 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 96.5 | 28.5 | 24.9 | 22.9 | 24.2 | 69.2 |

| MCCS | 15.4 | 22.7 | 61.9 | 16.6 | 47.8 | 35.6 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 93.8 | 11.4 | 7.1 | 15.0 | 13.6 | 6.4 |

| MDCS | 12.2 | 30.0 | 57.8 | 5.9 | 47.8 | 46.3 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 97.3 | - | 100 | - | - | 100 |

| MEC | 82.1 | 15.8 | 2.1 | 7.9 | 34.7 | 57.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | - | 100 | 10.9 | 0.3 | 5.2 |

| PCPT | 11.5 | 27.7 | 60.9 | 1.5 | 50.5 | 48.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 99.7 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 4.9 | 2.5 |

| PHS | 7.6 | 17.0 | 75.5 | 11.8 | 50.7 | 37.5 | 25.6 | 59.9 | 14.6 | 13.7 | 3.8 | 24.6 | 10.1 | 3.6 |

| PLCO | 56.4 | 39.1 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 52.2 | 40.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 18.6 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 10.7 | 0.3 |

| SELECT | 39.9 | 58.3 | 1.8 | 10.4 | 56.3 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 7.0 | 13.6 |

| SU.VI.MAX | 7.1 | 20.7 | 72.3 | 26.6 | 66.9 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | - | 100 | 2.2 | 9.9 | 6.5 |

Percentages exclude cases with missing values. Percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding. Stage and grade of disease are unavailable for some case patients; the percentages are shown in the “unknown stage” and “unknown grade” columns.

A tumour was categorised as advanced stage if it was tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage T3 or T4 and/or N1+ and/or M1, stage III–IV, or the equivalent. Aggressive disease was defined as tumours with TNM stage T4 and/or N1+ and/or M1 and/or stage IV disease and/or death from prostate cancer. High grade was defined as Gleason sum 8 or higher, or equivalent (undifferentiated).

For expansion of study names see Table 1. Abbreviation: y, year.

Associations between circulating vitamin D concentrations and prostate cancer risk

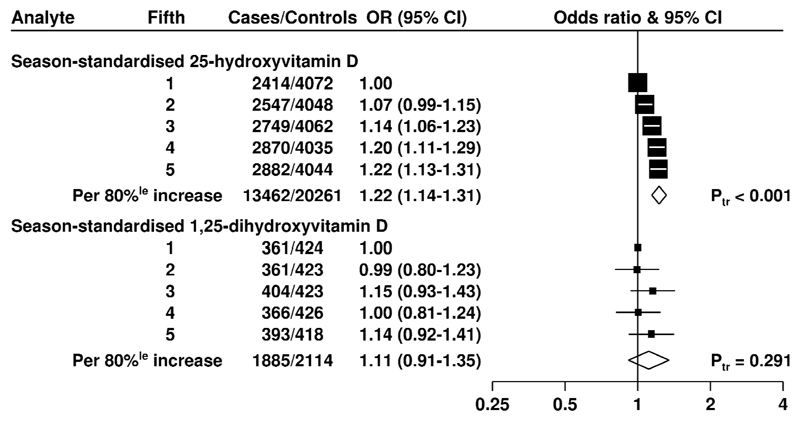

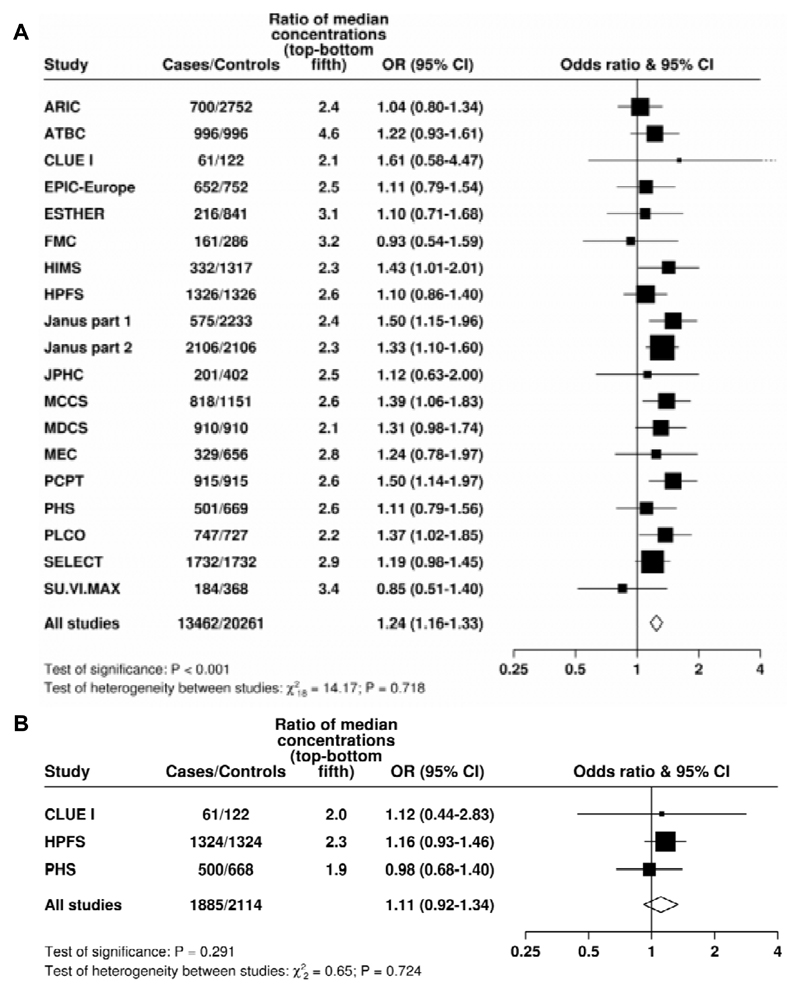

25(OH)D concentration was linearly positively associated with risk for total prostate cancer (Figure 1); the multivariate-OR for prostate cancer for men in the highest compared with the lowest study-specific fifth was 1.22 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.31; P trend < 0.001). The association was similar when only the matching factors were taken into account (Supplementary Figure 2) and there was no evidence of heterogeneity between the contributing studies (Figure 2A). When 25(OH)D was categorized into study-specific tenths, the OR for the highest versus the lowest tenth was 1.34 (1.20 to 1.49; P trend <0.001, Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for prostate cancer associated with study-specific fifths of season-standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentration in prospective studies.

Estimates are from logistic regression conditioned on the matching variables and adjusted for exact age, marital status, education, smoking, height and body mass index. Ptrend was calculated by replacing the fifths of vitamin D with a continuous variable that was scored as 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1 in the conditional logistic regression model. Abbreviations: 80%le= 80 percentile; CI = confidence interval; Ptr = Ptrend.

Figure 2. Study-specific odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for prostate cancer associated with an 80 percentile increase in season-standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentration.

A) Blood season-standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration; B) Blood season-standardised 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentration.

Estimates are from logistic regression conditioned on the matching variables within each study and without mutual adjustment for the other analytes. Heterogeneity in linear trends between studies was tested by comparing the X2 values for models with and without a (studies) x (linear trend) interaction term. For expansion of study names see Table 1.

There was no evidence of an association between 1,25(OH)2D concentration and risk for total prostate cancer (see Figures 1 and 2B). The association was similar when only the matching-factors were taken into account (Supplementary Figure 2).

In sensitivity analyses that used overall quintile cut-points of 25(OH)D across all studies combined (rather than study-specific cut-points), the ORs for total prostate cancer were materially unchanged (Supplementary figure 3). When the analyses were repeated using predefined cut-points for 25(OH)D, multivariable-adjusted ORs for total prostate cancer were 0.84 (0.76-0.93), 0.89 (0.84-0.95) and 1.07 (1.00-1.13), respectively, for men with 25(OH)D <30 (at risk for deficiency), 30-49 and ≥75 nmol/L compared to those with concentrations of 50-74 nmol/L (Supplementary Table 4).

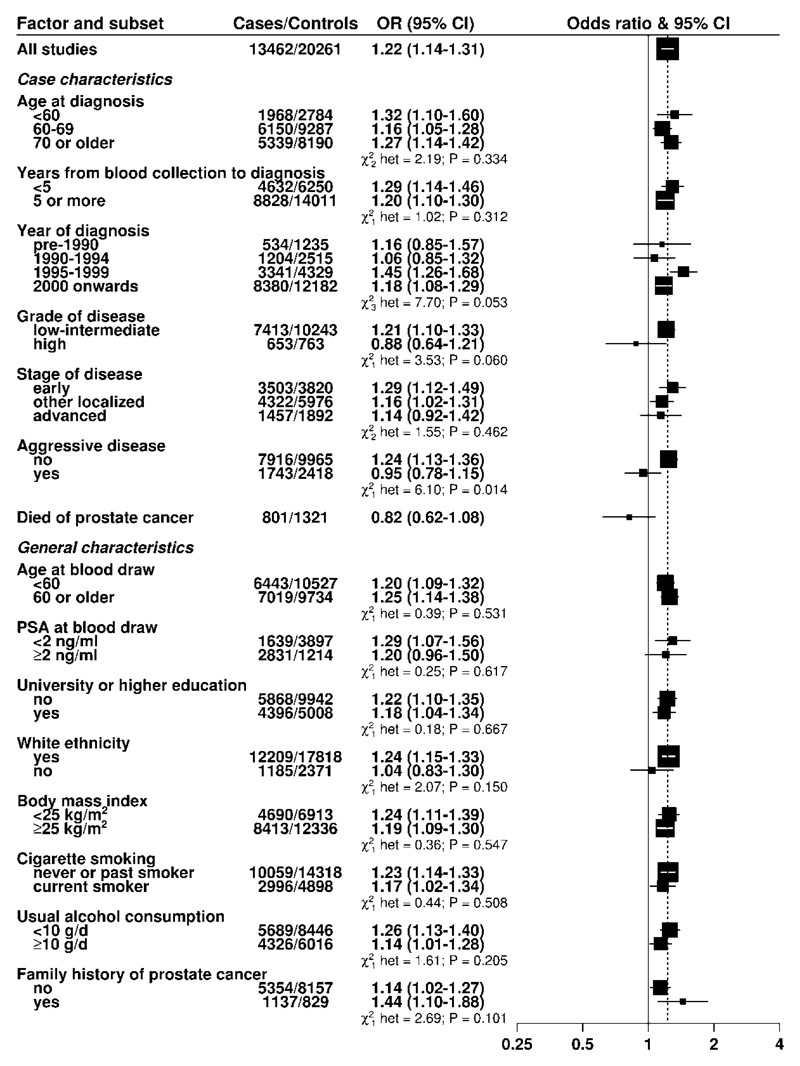

While there was no evidence of heterogeneity in the association of 25(OH)D with risk by stage of disease, there were differences by disease aggressiveness (P heterogeneity = 0.014): the OR for an 80-percentile increase in 25(OH)D was 1.24, 1.13-1.36 for non-aggressive disease (T1-T3/N0/M0) and 0.95, 0.78-1.15 for aggressive disease (T4, N1, M1 and/or fatal prostate cancer). Similar differences were also seen between low-intermediate and high-grade disease, although these differences were not statistically significant (Figure 3). There was no association between circulating 25(OH)D concentrations and fatal prostate cancer (Figure 3). Supplementary Figure 4 shows results from categorical analyses of the associations of study-specific fifths of 25(OH)D with risk for advanced stage, aggressive disease and high-grade prostate cancer.

Figure 3. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for prostate cancer associated with a study-specific 80 percentile increase in season-standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D in prospective studies for selected subgroups.

The odds ratios were conditioned on the matching variables and adjusted for exact age, marital status, education, smoking, height and body mass index. Tests for heterogeneity for the case-defined factors were obtained by fitting separate models for each subgroup and assuming independence of the ORs using a method analogous to a meta-analysis. Tests for heterogeneity for the other factors were assessed with a χ2-test of interaction between the subgroup and continuous trend test variable. Note that the number of cases for each tumour subtype may be fewer than shown in the baseline tables since here the analysis for each subgroup of a case-defined factor is restricted to complete matched sets for each category of the factor in turn; some matched sets contain a mixture of subtypes and while controls are allocated case-defined characteristics in equal proportion to the cases, 25(OH)D may be unknown for some participants, leading to incomplete matched sets.

Stage (early, T1 and/or stage I; other localized, T2/N0/M0 and/or stage II, and advanced, T3-T4/N1/M1 and/or stage III-IV), grade (low-intermediate, Gleason sum was < 8 or equivalent; high, Gleason sum was ≥ 8 or equivalent, and aggressive (T4/N1/M1 and/or stage IV and/or prostate cancer death). White ethnicity (89.4% yes, 10.6% no).

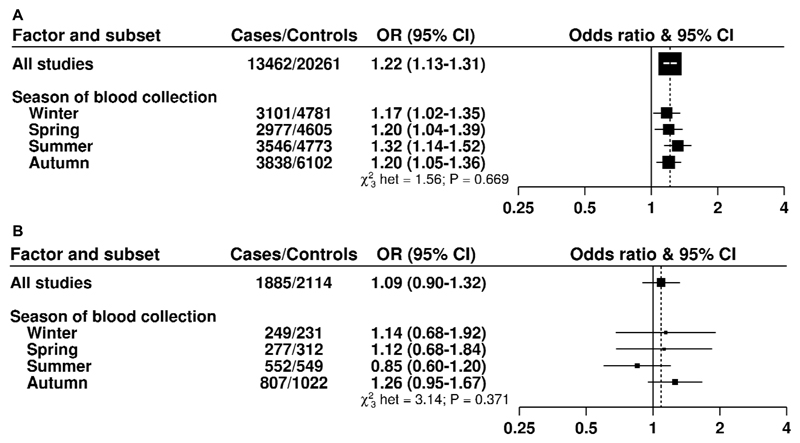

There was no evidence of heterogeneity in risk of total prostate cancer associated with 25(OH)D according to time to diagnosis or other participant characteristics (Figure 3), including season of blood draw (Figure 4A) or by circulating concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D, IGF-I, IGFBP-3, testosterone, free testosterone, SHBG or PSA (Supplementary Table 5A to 5G).

Figure 4. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for prostate cancer associated with a study-specific 80 percentile increase in 25-hydroxyvitamin D (A) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamind D (B) concentration by season.

The odds ratios were conditioned on the matching variables and adjusted for exact age, marital status, education, smoking, height and body mass index. Tests for heterogeneity were assessed with a χ2-test of interaction between the subgroup and continuous trend test variable. A) Blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration; B) Blood 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentration

For 1,25(OH)2D, there was no evidence of heterogeneity by season of blood draw (Figure 4B), time to diagnosis or other tumor characteristics (Supplementary Figure 5). There was some evidence of heterogeneity by family history of prostate cancer, with a positive association for men with a positive family history of the disease (P heterogeneity=0.03; multivariable-adjusted OR for an 80 percentile increase = 2.26, 95% CI 1.19-4.32, Supplementary Figure 4), although this was based on small numbers. There was no evidence of heterogeneity by season of blood draw (Figure 4).

Vitamin D concentrations in relation to other participant and sample characteristics

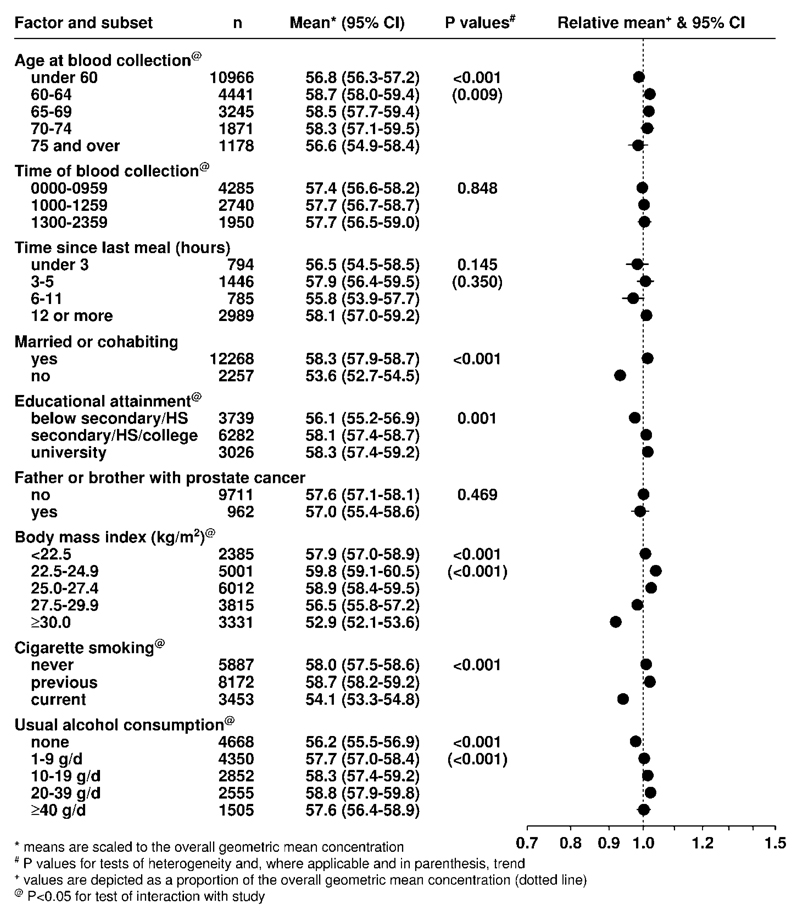

Concentrations of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D were significantly but not strongly correlated with each other (r = 0.13, p < 0.001). In the subset of control participants with data available on other analytes, circulating 25(OH)D concentration was weakly correlated with sex hormones and other analytes (Supplementary Table 6), but neither 25(OH)D nor 1,25(OH)2D concentration was correlated with PSA (r = 0.01 for both). After adjustment for age, 25(OH)D concentration was lower in men who were obese, current smokers, poorly educated, unmarried and non-drinkers (Figure 5). 1,25(OH)2D displayed generally similar associations (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 5. Geometric mean concentrations (95% confidence intervals) of season-standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D (nmol/L) for controls from all studies by various factors, adjusted for study and age at blood collection.

Means are scaled to, and depicted as a proportion of, the overall geometric mean concentration (dotted line). P values are for tests of heterogeneity and, where applicable in parentheses, trend.

Discussion

This collaborative analysis of individual participant data does not support the hypothesis that vitamin D deficiency and/or insufficiency increases the risk of prostate cancer. Higher 25(OH)D levels were associated with an increased risk of non-aggressive disease, with no association for aggressive disease. We also found no evidence that circulating concentration of 1,25(OH)2D was related to risk for prostate cancer, overall or by tumor characteristics.

This collaborative analysis includes information from the vast majority (>90%) for 25(OH)D and 85% for 1,25(OH)2D of the published prospective data. Of the 24 studies with published data on 25(OH)D, seven did not contribute data to this collaboration, all of which had fewer than 200 incident cases and reported inconsistent findings (8–13). Combining the results of the current analyses with those of six of the seven additional studies (for whom data could be extracted to perform a meta-analysis), did not change the overall finding (summary relative risk of highest compared with the lowest fifth of 25(OH)D = 1.21, 95% CI 1.13-1.30), suggesting that inclusion of participant-level data from these studies would not have materially altered the results. Two studies with published data on 1,25(OH)2D did not contribute data, one of which reported an inverse association (based on 181 cases, RR not given for 1,25(OH)2D alone) (10,14) and another that found no association (based on 136 cases) (9). Including these two studies would not have materially changed our results. Thus, we believe that the findings from the current study provide a reliable summary of the totality of the evidence on the association between circulating vitamin D concentrations and prostate cancer risk.

Our findings do not appear to support the evidence from experimental research using cell lines and animal models that vitamin D compounds may promote cell differentiation, inhibit prostate cancer cell growth and invasion, and stimulate apoptosis (15,16). While there are no published data from adequately powered randomized controlled trials for the effects of vitamin D supplementation on prostate cancer incidence, two large recent studies have exploited GWAS-identified variation in genes related to vitamin-D synthesis, metabolism and binding to study the possible relationship with prostate cancer risk. A Mendelian randomization analysis of data from up to 69,837 prostate cancer cases in the PRACTICAL and GAME-ON consortia found no evidence for an association with risk for either total (OR in PRACTICAL per genetically-determined 25 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentration = 0.95, 95% CI 0.80-1.13; P = 0.55) or aggressive prostate cancer (OR in GAME-ON = 1.14, 0.85-1.54; P = 0.38) (17).

It is possible that our finding of a positive association between overall and non-aggressive prostate cancer risk and circulating 25(OH)D concentration may be explained by detection bias, in that health-conscious men who may be more likely to have a higher sun exposure, a higher dietary intake of vitamin D and/or vitamin D supplementation, are more likely to have a PSA test or to seek medical attention with early symptoms. The observation that vitamin D deficiency was associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer and higher levels with an increased risk (particularly for non-aggressive disease) supports this hypothesis. Nonetheless, a positive association between 25(OH)D and prostate cancer risk was reported in both the PLCO and PCPT studies, in which almost all men had either regular PSA testing (as data were provided solely from the screening arm in PLCO and PCPT) or had an end-of-study biopsy (PCPT), suggesting that factors other than detection bias may be involved.

It is difficult to draw conclusions from the current pooled analyses of 1,25(OH)2D as only a small number of prospective studies have measured this analyte. While circulating 1,25(OH)2D concentrations are considered to be tightly regulated within a narrow range (18), we found some evidence of seasonal variation in 1,25(OH)2D concentrations, similar to that of 25(OH)D, and also differences in concentrations according to age, adiposity, cigarette smoking status and alcohol consumption. It is difficult to determine the extent to which these associations are due to cross-reactivity of the 1,25(OH)2D assay with 25(OH)D (or other molecules), although the correlation between 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D was weak (r=0.13) and there was no evidence for an association between 1,25(OH)2D and prostate cancer risk.

A number of previous studies have evaluated the joint association of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D with prostate cancer risk (9,19–21), but their sample sizes were small. We found no evidence that the association of prostate cancer risk with 25(OH)D is modified by circulating concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D, although even in this collaborative pooled dataset, there are still relatively few cases (n=1,885) with data on both vitamin D analytes. It has also been hypothesized that vitamin D may influence tumor growth by modulating the action of growth factors, such as IGF-I, that normally stimulate proliferation (16), for example by stimulating the release of IGFBP-3 (22). We observed weak correlations of circulating 25(OH)D or 1,25(OH)2D concentrations with IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2 and IGFBP-3 concentrations and with levels of other blood biomarkers (e.g. free testosterone or PSA), and there was no evidence of modification of the association of 25(OH)D with risk according to these biomarkers.

This study has some limitations. The calculated relative risks were based on single measurements of vitamin D, which may not accurately reflect long-term circulating concentration. Several studies have found moderate correlations between two measures of 25(OH)D, even when the samples were not taken at the same time of the year, with correlations between 0.42 and 0.70 in blood taken between 3 to 14 years apart (reviewed in (23)). These findings suggest that a single measure of circulating 25(OH)D is an informative measure of vitamin D status, at least over the medium term. The published prospective data on vitamin D and risk for aggressive prostate cancer subtypes are still relatively limited. Thus, even in this pooled analysis, the total number of cases with aggressive disease and data on 25(OH)D is relatively small (n=1,446), therefore the results by tumor sub-type should be interpreted with some caution. Moreover, we don’t have detailed data on other sun exposure measures, such as solar radiation levels in each study location, which would also vary within each individual study depending on where each participant lives. Finally, more than 95% of participants included in this pooled analysis were of White ethnicity, and results may therefore not be generalizable to non-White populations.

In summary, this collaborative analysis of the worldwide data on circulating vitamin D and prostate cancer risk suggests that a high vitamin D concentration is not associated with a lower risk of prostate cancer. Rather, the findings suggest that men with elevated circulating concentrations of 25(OH)D are more likely to be diagnosed with non-aggressive prostate cancer, though this may be due to detection bias. There was no evidence for an association with aggressive disease.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

This international collaboration comprises the largest prospective study on blood vitamin D and prostate cancer risk and shows no association with aggressive disease but some evidence of a higher risk of non-aggressive disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank the men who participated in the collaborating studies, the research staff, the collaborating laboratories and the funding agencies in each of the studies. The authors are solely responsible for the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the article, and decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK grant C8221/A19170 and involved centralized pooling, checking and data analysis. Details of funding for the original studies are in the relevant publications (and see Supplementary Materials). The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The authors in the writing team had full access to all data in the study. The corresponding author had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The EHNBPCCG data are not suitable for sharing, but are suitable for research involving further analyses in collaboration with the Cancer Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- EHNBPCCG

Endogenous Hormones, Nutritional Biomarkers and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group

- ESTHER

Epidemiologische Studie zu Chancen der Verhütung, Früherkennung und optimierten THerapie chronischer ERkrankungen in der älteren Bevölkerung

- IGF-I

insulin-like growth factor-I

- IGFBP3

IGF binding protein-3

- OR

odds ratio

- PCPT

Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial

- PLCO

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- SHBG

sex hormone-binding globulin

- TNM

tumor-node-metastasis

- 1,25(OH)2D

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: RB is a shareholder of AS Vitas, Oslo, Norway. The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schwartz GG, Hanchette CL. UV, latitude, and spatial trends in prostate cancer mortality: all sunlight is not the same (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1091–101. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz GG, Hulka BS. Is vitamin D deficiency a risk factor for prostate cancer? (Hypothesis) Anticancer Res. 1990;10:1307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert R, Martin RM, Beynon R, Harris R, Savovic J, Zuccolo L, et al. Associations of circulating and dietary vitamin D with prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:319–40. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, Key TJ, Endogenous H, Prostate Cancer Collaborative G Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:170–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price AJ, Travis RC, Appleby PN, Albanes D, Barricarte Gurrea A, Bjorge T, et al. Circulating Folate and Vitamin B and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Collaborative Analysis of Individual Participant Data from Six Cohorts Including 6875 Cases and 8104 Controls. Eur Urol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Reeves GK. Pooling biomarker data from different studies of disease risk, with a focus on endogenous hormones. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:960–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington (DC): 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuohimaa P, Tenkanen L, Ahonen M, Lumme S, Jellum E, Hallmans G, et al. Both high and low levels of blood vitamin D are associated with a higher prostate cancer risk: a longitudinal, nested case-control study in the Nordic countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:104–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN, Lee J, Kolonel LN, Chen TC, Turner A, et al. Serum vitamin D metabolite levels and the subsequent development of prostate cancer (Hawaii, United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:425–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1008875819232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corder EH, Guess HA, Hulka BS, Friedman GD, Sadler M, Vollmer RT, et al. Vitamin D and prostate cancer: a prediagnostic study with stored sera. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett CM, Nielson CM, Shannon J, Chan JM, Shikany JM, Bauer DC, et al. Serum 25-OH vitamin D levels and risk of developing prostate cancer in older men. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1297–303. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs ET, Giuliano AR, Martinez ME, Hollis BW, Reid ME, Marshall JR. Plasma levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and the risk of prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:533–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordonez-Mena JM, Schottker B, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Olsen A, Halkjaer J, et al. Pre-diagnostic vitamin D concentrations and cancer risks in older individuals: an analysis of cohorts participating in the CHANCES consortium. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:311–23. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corder EH, Friedman GD, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N. Seasonal variation in vitamin D, vitamin D-binding protein, and dehydroepiandrosterone: risk of prostate cancer in black and white men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:655–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swami S, Krishnan AV, Feldman D. Vitamin D metabolism and action in the prostate: implications for health and disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleet JC. Molecular actions of vitamin D contributing to cancer prevention. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimitrakopoulou VI, Tsilidis KK, Haycock PC, Dimou NL, Al-Dabhani K, Martin RM, et al. Circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of seven cancers: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gann PH, Ma J, Hennekens CH, Hollis BW, Haddad JG, Stampfer MJ. Circulating vitamin D metabolites in relation to subsequent development of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Stampfer MJ, Hollis JB, Mucci LA, Gaziano JM, Hunter D, et al. A prospective study of plasma vitamin D metabolites, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and prostate cancer. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Hollis BW, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Plasma 1,25-dihydroxy- and 25-hydroxyvitamin D and subsequent risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:255–65. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000024245.24880.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng L, Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Identification of a functional vitamin D response element in the human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1109–19. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng JE, Hovey KM, Wactawski-Wende J, Andrews CA, Lamonte MJ, Horst RL, et al. Intraindividual variation in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D measures 5 years apart among postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:916–24. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.