Abstract

Background

Quantitative T2 and diffusion MRI indices inform about tissue state and microstructure, both of which may be affected by pathology before tissue atrophy.

Purpose

To evaluate the capability of both volumetric and quantitative MRI (qMRI) of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (EC) for classification of amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD).

Study Type

Retrospective cross-sectional study.

Population

Consecutive cohorts of healthy age-matched controls (n=62), aMCI patients (n=25) and ADD patients (n=14).

Field Strength and Sequence

3T using T1-weighted imaging, T2-weighted imaging, T2 relaxometry and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Assessment

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and paired associate learning (PAL) tests for cognitive state. Hippocampal subfield volumes by the automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields system from structural brain images. T2 relaxation time and DTI indices quantified for hippocampal subfields. The fraction of voxels with high T2 values (>20 ms above subfield median) was calculated and regionalised for hippocampus and EC.

Statistical Tests

Support vector machine (SVM) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses from cognitive and MRI data.

Results

Quantitative MRI classified aMCI and ADD with excellent sensitivity (79.0% and 94.5%, respectively) and specificity (85.6% and 86.1%, respectively), superior to volumes alone (70.0% and 84.5% for respective sensitivities; 82.2 and 91.1 for respective specificities) and similar to cognitive tests (61.7% and 87.5% for respective sensitivities; 88.2% and 90.7% for respective specificities). Regions of high T2 are dispersed throughout each hippocampal subfield in aMCI and ADD with higher concentration than controls, and was most pronounced in the EC. No other individual qMRI marker than EC volume can separate aMCI from ADD, however.

Data Conclusion

Quantitative MRI markers of hippocampal and entorhinal tissue states are sensitive and specific classifiers of aMCI and ADD. They may serve as markers of a neurodegenerative state preceding volume loss.

Keywords

T2 relaxometry, diffusion tensor imaging, hippocampus, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease dementia

Keywords: hippocampus, dementia, MRI volumetry, T2 relaxation time, diffusion tensor imaging

Introduction

The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD), which may be preceded by a prodromal phase of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), although MCI does not imply AD as an eventuality (1). There is considerable interest in early detection of ADD by imaging. This is made challenging by its clinical presentation being retarded as compared to its pathology (2), and by the pathology being difficult to detect in vivo (3). The importance of early detection is driven by several factors. Firstly, it is generally thought that any novel intervention is more likely to arrest development of ADD rather than reverse it (4). Secondly, and with the first point in mind, developing any such intervention will not be straightforward without the ability to recruit participants at a sufficiently early stage to validate that intervention. Likely to reflect inadequate inclusion of participants, 172 human trials on dementia drugs failed up to 2008 (5), considerably exceeding the average rate of failure of clinical trials in general (6).

Commonly used diagnostic strategies are dominated by assessment of memory and behavioral symptoms and use of a “structural” imaging modality typically to make an assessment of gross brain structure and tissue loss (2). Specific molecular imaging (3) or cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measurement are rarely available in clinical practice (7). Atrophy is not a direct marker of pathology per se, but of the consequence of pathology. The characterisation of brain structure and atrophy has nevertheless proved useful in demonstrating the existence of a spectrum of types of dementia and states, and in monitoring disease progression (2,8,9). Widespread cortical thinning is generally seen in ADD, as well as hippocampal atrophy, with the rate of atrophy being generally increased in ADD. However, there are several distinct patterns of atrophy observable, and no single structural biomarker of ADD. Hippocampal atrophy, or its rate, adds confidence in diagnosis, but hippocampal atrophy is absent in 11% of ADD cases (8). Nevertheless, structural imaging, preferably by MRI, is recommended in all patients by the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) and therefore is a modality that could be further exploited with minimal extra cost per patient (10).

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) provides various indices whose values are determined by the microstructural features of tissues. It has been reported that fractional anisotropy (FA) is decreased and mean diffusivity increased in the hippocampus in ADD (9,11). The pathology of ADD is widespread, and includes white matter (WM). DTI has also provided evidence of microstructural tissue alteration in ADD in WM (9,11,12), and that WM changes in tissue state may be observed by DTI before atrophy (13–15). T2 relaxometry studies have reported either shortened (16), normal (17) or prolonged (18,19) numeric values for T2 in hippocampi of ADD patients.

Our objectives in this study were to examine the utility of quantitative MRI (in particular T2 relaxometry and DTI) as a non-invasive assay of the tissue state of hippocampal subfields and the entorhinal cortex (EC), structures know to be affected by early AD pathology (20), with a view to detecting differences in tissue state between healthy older controls, persons with MCI and those with ADD to as a spectrum of clinical presentation for AD. In the healthy older population, there will be relatively few people with significant AD pathology (21) and in the ADD group we expect almost all participants to have AD pathology, although one should bear in mind that patients here were diagnosed using standard clinical tests and diagnostic accuracy is around 70-90% (22). The aMCI group are more heterogenous and we know that at least around 50% will develop ADD, but others will remain stable and are presumed not to have AD pathology (23). In order to guide early diagnosis, we are particularly interested in tests that will differentiate between the healthy control group and participants with MCI (with more variability in the MCI group). Therefore, in particular, we consider the following three hypotheses:

First, quantitative T2 and diffusivity distributions of hippocampal subfields and the EC, by virtue of the transition to a neurodegenerative state preceding (or concurrent with) atrophy in aMCI and ADD, will differ according to clinical state of the disease. The transition to a neurodegenerative state will lead to a more heterogeneous microstructural environment, measurable by increased widths of T2 and diffusivity distributions, equivalent to the statement that a greater proportion of voxels will deviate from a state representative of healthy tissue in non-healthy individuals. Second, quantitative MRI, by virtue of sensitivity to tissue quality rather than quantity, will have different or independent capacity to classify clinical state of the disease to tissue quantity. Quantitative biomarkers of tissue state will therefore be de-correlated from volume. Third, the distinct distributions of compromised tissue state in different limbic system components will confer distinct T2 distributions on each. Improved capacity to classify clinical state of the disease will be obtained by making separate use of T2 distributions from each component, the classifier otherwise having to absorb variance due to cell viability.

Methods and Materials

Participant cohort

We analysed the first 101 volunteer participants, recruited as part of the institutional hippocampal imaging study, where longitudinal data collection is ongoing. 62 were healthy controls with no known brain disorder (38 female, age range 49 to 87, mean age 68), 25 were aMCI (12 female, age range 51 to 88, mean age 73), and 14 were ADD patients (10 female, age range 56 to 89, mean age 72).

Amnestic MCI diagnosis was based on the criteria given by Petersen et al (24) and, for inclusion, all participants had to have symptoms of memory impairment and/or be 1 standard deviation below that expected on a memory test. Thus, we have included both amnesic MCI and multidomain MCI patients where amnesia as a significant feature. Participants underwent the paired associative learning (PAL) task of the CANTAB toolbox (25) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Cognitive testing was within 6 weeks of MRI. All participants gave informed consent and ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board.

Image acquisition

All imaging was performed using a Siemens Magnetom Skyra 3T system equipped with a parallel transmit body coil and 32-channel head receiver array coil. The imaging protocol comprised a 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE, 2D multi-contrast spin-echo and 2D DTI with the following parameters: MPRAGE: coronal, TR 2200 ms, TE 2.42 ms, TI 900 ms, flip angle 9°, acquired resolution 0.68 x 0.68 x 1.60 1.60 mm3, acquired matrix size 152 x 320 x 144, reconstructed resolution 0.34 x 0.34 x 1.60 mm3 (after 2-fold interpolation in-plane by zero-filling in k-space), reconstructed matrix size 540 x 640 x 144, GRAPPA factor 2 (26), time 5:25 min. Multi-contrast spin-echo: TR 4500 ms, TE 12 ms, number of echoes 10, echo spacing 12 ms acquired resolution 0.68 x 0.68 x 1.7 mm3 inclusive of 15% slice gap, acquired matrix size 152 x 320, 34 slices, interleaved slice order, reconstructed resolution 0.34 x 0.34 x 1.7 mm3 (after 2-fold interpolation in-plane by zero-filling in k-space, and inclusive of 15% slice gap), reconstructed matrix size 540 x 640, 34 slices, GRAPPA factor 2, time 11:07 min. DTI: axial, TR 3800 ms, TE 85.2 ms, b-value 1000 s/mm2, number of gradient directions 60 (full-sphere), acquired and reconstructed resolution 2 x 2 x 2 mm3 inclusive of 10% slice gap, matrix size 122 x 122, 60 slices, GRAPPA factor 2, multi-band factor 2 (27), time 4:30 min. Note that the multi-echo spin echo did not have full-brain coverage, its anterior-posterior coverage only extending around 1 cm anterior and posterior to the head and tail of the hippocampus respectively, with the acquisition tilted such that the hippocampal body created an axis normal to the slice acquisition plane.

Image processing

Diffusion tensors were fitted using DTIFIT after eddy current correction using the EDDY_CORRECT program of FSL (28). T2 maps were computed by a voxel-wise fit of a mono-exponential function in a logarithmic space, excluding the first echo. This was done since the pulse sequence allows the passage of both spin and stimulated echoes due to the use of identical crusher gradients astride each refocusing pulse, though the first echo contains only spin echo contributions. A single T2-weighted image was prepared by summing over the echo times.

Hippocampal subfield boundaries were demarcated using the software package ASHS (29). This requires a T1-weighted and T2-weighted input, of which the T2-weighted input must have sufficient resolution in the coronal plane for subfield boundary demarcation and dimensions ordered with the AP dimension the 3rd dimension. These criteria were fulfilled by the sum-over-echoes image, with dimensions permuted using FSL SWAPDIM. The T1-weighted image was typically provided without brain extraction and the T2-weighted image with brain-extraction. All ASHS masks were visually inspected and if low quality was evident, the T1-weighted image was brain-extracted using the VBM8 toolbox of SPM8, and the sum-over-echoes T2-weighted image also corrected for bias field using FSL FAST. Typical set of TE series images and corresponding echo summed T2-weigthed images and T2 and R2 maps are shown in Supplementary Information (SI, Figure S1). All TE series were visually inspected for possible motion artefacts, if motion was evident, the case was excluded. Signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) for volumes encompassing hippocampi from TE=24ms and TE=120ms images are given in SI (Figure S1). Volumes of subfields as well as T2 distribution statistics were calculated directly from these masks and by applying them to the T2 maps. Using Matlab toolbox T2 distributions were fitted into Burr function to determine median average distribution. Potential effect of Gaussian noise on T2 Burr distribution was addressed by simulations (Figure S2). The conclusion from the simulations is that T2 Burr distribution is not influenced by Gaussian noise, rather noise would convert the T2 distribution to close-to-Gaussian, which was not observed in the current data set. For each subfield, as well as the whole hippocampus and EC, masks of “high T2” voxels were also prepared, defined for a particular region as voxels for which the T2 was greater than 20 ms above the median T2 for that region. 20 ms was chosen for the filter as it is a good approximation to the average standard deviation of hippocampal T2 for a healthy participant at age 60 (Figure S3), thus, voxels within the filter capture ~95% of observations for healthy participants aged 60 or younger.

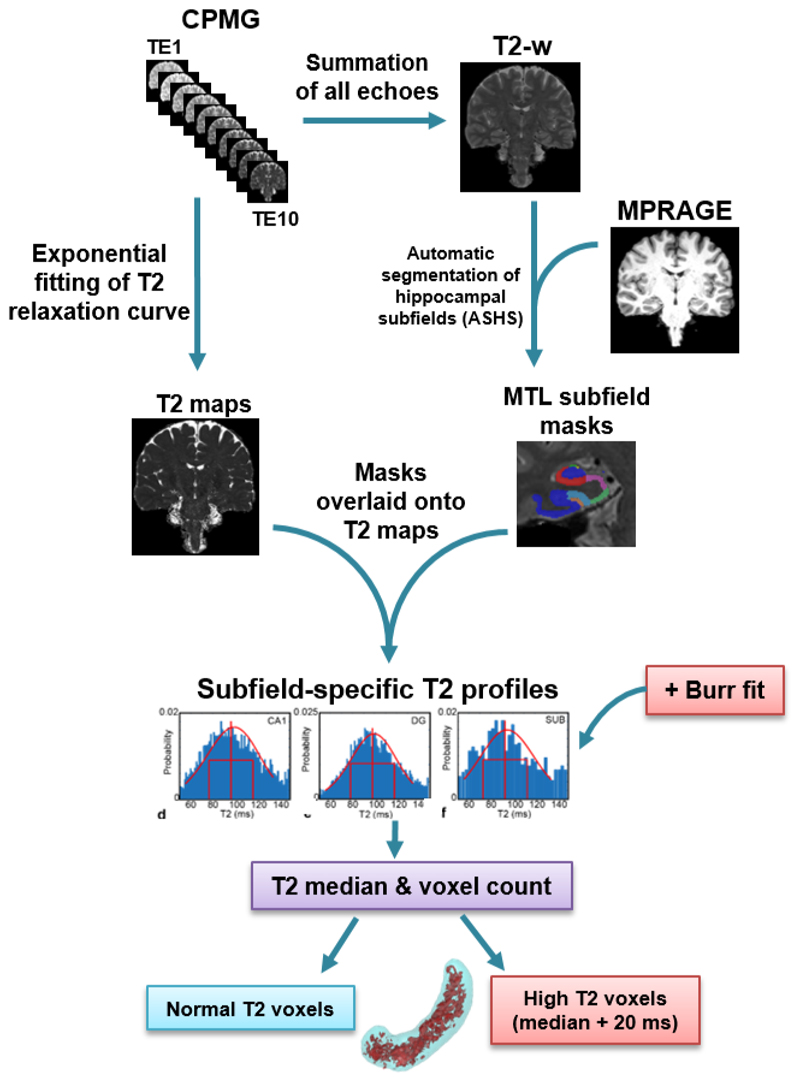

To regionalize where T2 was likely to be elevated within a group (control, aMCI, or ADD) within each hippocampal subfield, or in the EC, the masks were required in a common template space, for which we used the MNI space. T2-weighted images were registered to T1-weighted images using a rigid-body transformation with FSL FLIRT, and T1-weighted images registered non-linearly to the MNI template using FSL FNIRT. The probability of a voxel having a T2 outside the filter could then be obtained simply by summing the high-T2 masks and dividing by the number of participants. This was done for each participant group and each subfield separately. Image data processing pipeline is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of T2 image data processing. CPMG multi-echo images are used to produce both echo-summed T2-weighted (T2-w) and absolute T2 images (T2 maps). T2-weighted images are used together with T1-weighted MPRAGE images as inputs to the automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields (ASHS) to yield subfield masks. These subfield masks are transferred onto the T2 maps to produce subfield-specific T2 profiles. The T2 profiles are fitted to Burr function to identify normal and high T2 voxels in each subfield. The percentage of high T2 voxels is calculated for each subfield from these data.

DTI images were registered to T2 space using FSL FLIRT. Whole-hippocampus statistics were calculated for the fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), radial diffusivity (RD) and axial diffusivity (AxD). Prior to applying the whole-hippocampus masks, they were eroded by 1 voxel around the exterior to mitigate partial volume effects possible from the coarser resolution of the DTI acquisition. All image registrations were performed using FSL (30).

Statistics

The capability of sets of variables to classify cognitive groups was assessed by training support vector machine (SVM) classifiers (with 2nd order polynomial kernel), predicting posterior probabilities and computing receiver operating characteristics (ROC) with statistics and machine learning tool in Matlab. Due to the imbalanced group sizes, a cross-validation procedure was implemented to draw random samples of equal sizes from each group, with the sample size defined so as to be one smaller than the smallest group. 250 iterations were performed, and the mean ROC statistics were kept, with their standard deviations across the iterations used as uncertainties. This analysis was carried out for the following sets of variables: 1. Volumes: {CA1, CA3, dentate gyrus (DG), subiculum (SUB), whole_hippo, EC}; 2. T2 median absolute deviations (T2mad): {cornu ammonis 1 (CA1), CA3, dentate gyrus (DG), subiculum (SUB), whole hippocampus (whole_hippo), EC}; 3. fraction of high-T2 voxels: {CA1, CA3, DG, SUB, whole_hippo, EC}; 4. DTI median absolute deviation (DTImad) across whole hippocampus: {FA, MD, RD, AxD}; 5. Cognitive variables: {MoCA_score, PAL_score, PAL_max_level, PAL_mean_reaction_time}. Sets 1,2,3 and 4 were then combined to an “all MRI” set. Sets 1, 3 and 5 were also combined to produce the best-performing set. In both former cases, due to the large set sizes, prior to SVM/ROC, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, retaining the first 5 principal components only, to reduce the dimensionality and speed up classification with minimal information loss.

Shapiro-Wilk tests for normality were performed on all MRI variables for each subfield. Where all groups were normally distributed, group differences in MRI parameters were assessed using one-way ANOVAs, with Tukey’s post-hoc test for pair-wise group comparisons. Where tests for normality were not fully met, Independent Kruskal-Wallis Tests were used to assess group differences, with Dunn’s post-hoc test for pair-wise group comparisons. ROC comparisons were assessed with multiple t-tests, corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini-Krieger-Yekutieli method. All statistical analyses were performed using Matlab version 2016b (with statistics and machine learning toolbox), IBM SPSS Statistics v24 and GraphPad Prism v7.

Results

Classifying groups with MRI and cognitive tests

Table 1 shows statistical data for hippocampal subfields and EC volumes, T2mad, high-T2 fraction and DTImad data. It is evident that while volumes, T2mad and high-T2 fraction were different in both aMCI and ADD patients relative to controls, however, none of the MRI measures were different between aMCI and ADD participants.

Table 1.

Pairwise group comparisons of all MRI parameters.

| Vols | CA1 | CA3 | DG | SUB | Total HC | EC |

| C / aMCI | .001 | K-W test | .004 | .031 | .003 | .096* |

| C / AD | < .001 | not | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001* |

| AD / aMCI | 1.000 | significant | .535 | .350 | .710 | .019* |

| T2mad | CA1 | CA3 | DG | SUB | Total HC | EC |

| C / aMCI | < .001 | < .001 | .003 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001* |

| C / AD | .006 | < .001 | .013 | < .001 | .001 | < .001* |

| AD / aMCI | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .522* |

| HighT2 | CA1 | CA3 | DG | SUB | Total HC | EC |

| C / aMCI | < .001 | < .001 | .011 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 |

| C / AD | .005 | .001 | .015 | < .001 | .004 | < .001 |

| AD / aMCI | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| DTImad | FA | MD | RD | AxD | ||

| C / aMCI | K-W test | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| C / AD | not | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| AD / aMCI | significant | .562 | .723 | .422 | ||

Unless denoted by an asterisk (*), cells show p-values for Dunn’s post-hoc test following a significant Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) test for each subfield or DTI parameter. Asterisks (*) denote p-values calculated from ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc, as data in all three groups were normally distributed. Where K-W test was not significant, pairwise comparisons were not conducted. Bold values indicate P<0.05. Key: Abbreviations as defined in the text, Vols = volumes; Total HC = total hippocampal volume

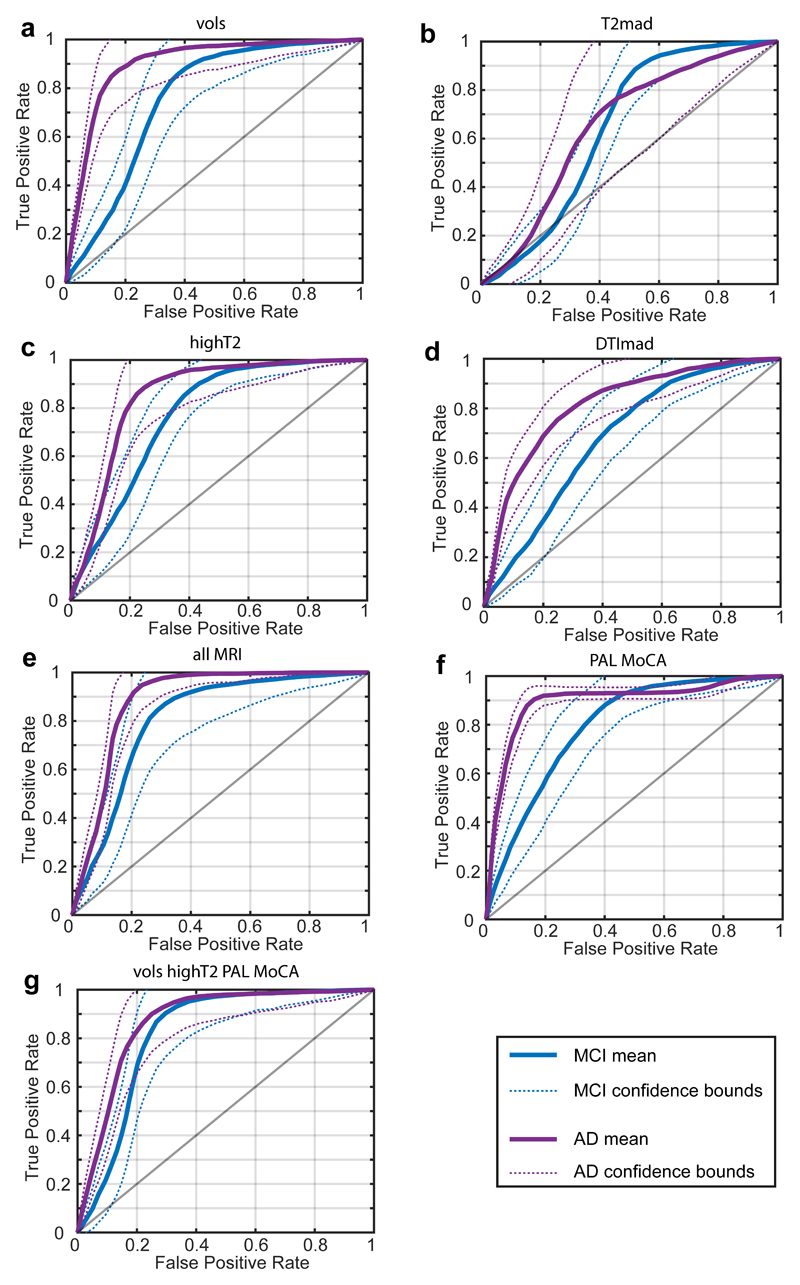

Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for different sets of variables, using the group-balanced cross-validation procedure. It is evident that most sets perform well, but often struggle for sensitivity of detection of aMCI, despite generally very good specificity for all groups. The combination of all MRI variables results in a classifier with very similar performance to the cognitive tests MoCA and PAL combined, and which out-performs these cognitive tests for sensitivity of detection of aMCI. The sets which had the best classifying power were combined on the premise that they should result in an optimal classifier, which indeed they did. The optimal classifier, combining PAL, MoCA, hippocampal subfield volumes and the subfield-wise fractions of high-T2 voxels accomplished the highest sensitivity for aMCI detection, and all other parameters either optimal or within the uncertainty bounds indistinguishable from optimal.

Figure 2.

ROC curves for the classification of aMCI and ADD groups using different sets of MRI and cognitive variables. Panel (a) shown ROC curves for hippocampal subfield and EC volume; panel (b) for T2mad; panel (c) for high T2 fractions; panel (d) for collective indices of DTImad; panel (e) for allMRI indices; panel (f) for cognitive tests, PAL and MoCA and panel (g) for combined MRI volumes, highT2 voxels and cognitive test.

Table 2 shows the ROC statistics for the different sets of variables. For separation of aMCI patients and controls all MRI variables (sets 1-4 combined) performed significantly better than volumes alone (set 1), as shown by Benjamini-Krieger-Yekutieli analysis for ROC curve metrics (Table S1). The optimum data set outperformed any of individual MRI set, but all MRI variables were as good as the optimum combination for aMCI cohort. In ADD patients quantitative MRI was similarly specific, with high-T2 fraction having superior sensitivity than volumes (Table 2).

Table 2.

ROC statistics for SVM classifiers of cognitive group using different sets of observations.

| Set | Set | Group | AUC | σAUC | TPR | σTPR | 1-FPR | dFPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vols | 1 | C | 92.7 | 7.9 | 93.6 | 13.8 | 90.5 | 7.4 |

| 1 | aMCI | 75.6 | 15.5 | 70.0 | 34.0 | 82.2 | 13.5 | |

| 1 | ADD | 90.0 | 12.6 | 84.5 | 21.3 | 91.1 | 7.9 | |

| T2mad | 2 | C | 93.1 | 9.5 | 87.3 | 12.8 | 93.3 | 5.1 |

| 2 | aMCI | 64.5 | 13.2 | 38.2 | 42.3 | 87.2 | 16.8 | |

| 2 | ADD | 65.5 | 26.1 | 57.4 | 43.0 | 86.6 | 12.2 | |

| High-T2 | 3 | C | 94.6 | 4.2 | 90.6 | 8.5 | 93.6 | 5.6 |

| 3 | aMCI | 77.1 | 12.5 | 62.6 | 33.5 | 85.2 | 13.9 | |

| 3 | ADD | 85.3 | 14.4 | 86.1 | 23.8 | 85.6 | 10.5 | |

| DTImad | 4 | C | 88.0 | 11.1 | 78.3 | 19.1 | 89.6 | 7.4 |

| 4 | aMCI | 68.5 | 12.5 | 36.9 | 32.6 | 91.7 | 10.3 | |

| 4 | ADD | 81.7 | 10.6 | 64.3 | 19.2 | 90.4 | 8.8 | |

| Cog | 5 | C | 95.3 | 3.4 | 94.2 | 6.1 | 93.0 | 4.8 |

| 5 | aMCI | 79.5 | 12.1 | 61.7 | 31.5 | 88.2 | 12.2 | |

| 5 | ADD | 89.6 | 5.0 | 87.5 | 8.1 | 90.7 | 6.6 | |

| allMRI | 1,2,3,4 | C | 95.2 | 6.6 | 98.4 | 9.4 | 93.1 | 7.8 |

| 1,2,3,4 | aMCI | 81.0 | 17.4 | 79.0 | 32.2 | 85.6 | 12.1 | |

| 1,2,3,4 | ADD | 88.8 | 9.7 | 94.5 | 13.5 | 86.1 | 10.7 | |

| best | 1,3,5 | C | 97.5 | 6.9 | 99.2 | 6.7 | 97.0 | 6.7 |

| 1,3,5 | aMCI | 82.2 | 15.3 | 87.7 | 23.9 | 83.2 | 12.3 | |

| 1,3,5 | ADD | 87.1 | 13.5 | 87.4 | 19.6 | 86.7 | 11.5 | |

AUC = area under curve, σAUC = standard deviation of AUC, TPR = true positive rate (sensitivity), σTPR = standard deviation of TPR, FPR = false positive rate (1-specificity). These are given as the mean of a group-balanced leave-out-one wrt smallest group procedure ± the standard deviation, as percentages.

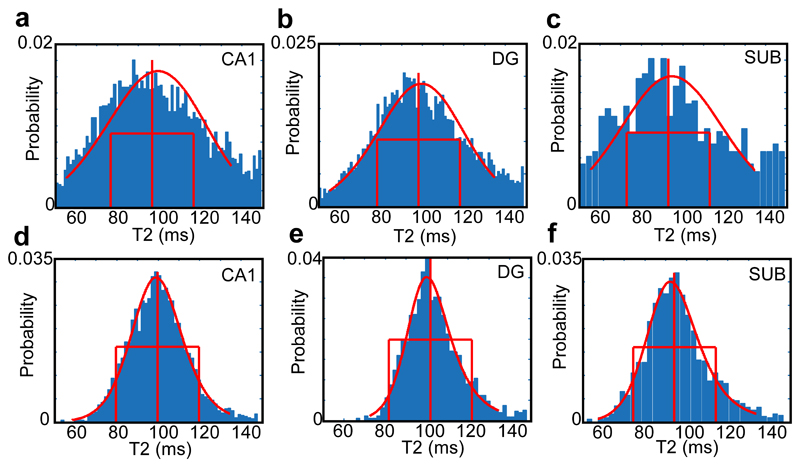

The inclusion of age did not improve classification accuracy. The use of statistics describing the centre of average of T2 or DTI scalar distributions (mean, median, mode or parametric descriptions) was also not useful. Other distribution width and shape parameters were explored for T2, FA, MD, RD and AxD but the sole use of median absolute deviation was most effective and made a meaningful contribution to classifying groups. Given the typical width of T2 distributions in hippocampal subfields in a control and an aMCI patient (Figure 3), it is not surprising that a centre-point parameter is not useful.

Figure 3.

Distributions of T2 within different hippocampal subfields for an aMCI participant aged 69 (top row) and a younger control participant aged 49 (bottom row). The increasing width and fraction of high-T2 voxels in the older MCI case is clear. The median, 20 ms lines, and the fit of a Burr distribution are shown in red.

The z-scores for t-tests for all parameters are shown as boxplots (Figure S4). We found that classifiers using parameters from all subfields separately, as shown in the Figure 2 and Tables 1 and 2, out-performed the use of the total hippocampal measures alone (not shown).

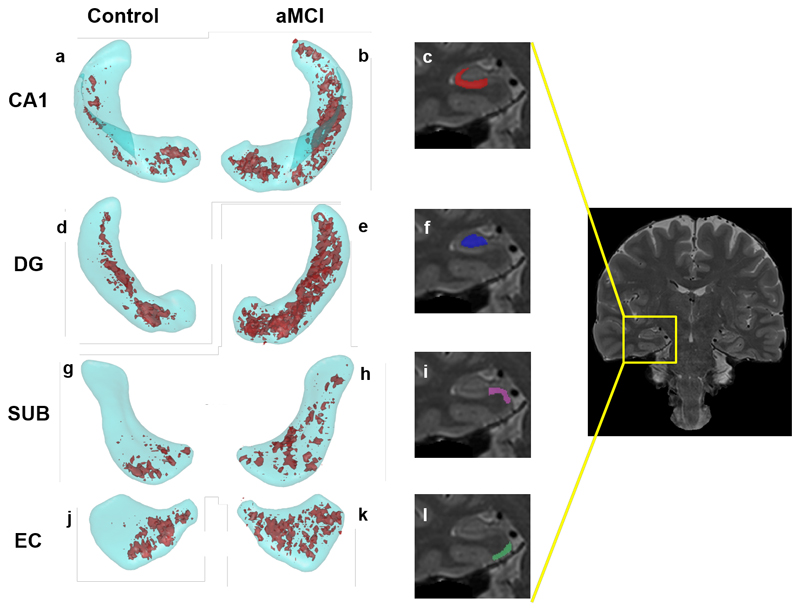

Localising high-T2 voxels

Given that the width of hippocampal subfield and EC T2 distributions and fractions of high-T2 voxels, but not their centre-points or averages, have good group classifying power, we explored whether there was any regionalisation of high-T2 voxels in hippocampal subfields and the EC. This was performed in MNI space for the control, aMCI and ADD groups separately. Figure 4 shows that high-T2 regions are distributed more or less randomly throughout each subfield, but are more prevalent in the aMCI group relative to control group. Scatter plots of total hippocampal and EC volumes vs high-T2 fractions are given (Figure S5), The highest high-T2 burden in the aMCI and ADD groups is in the EC, but this is not significantly higher than in any hippocampal subfield at the p < 0.05 level (Figure S6). The fact that the high-T2 regions are not in the proximity of outer hippocampal boundaries discounts the possibility that they are due to macroscopic partial volume effects with the CSF of the surrounding temporal horn.

Figure 4.

Locations of high-T2 voxels at the 15% level (15% of participants in the group have a high-T2 value) in the Control (a,d. g, j) and aMCI (b, e, h, k) groups for selected subfields and the EC. The subfields are shown in cyan, the 15% probability high-T2 regions in red. Zoomed sections from the coronal image on the right show a slice through CA1 (c); dentate gyrus (f); subiculum (i) and entorhinal cortex (l).

Discussion

We have shown that distributions of T2 profiles in the hippocampal subfields and EC are broader in aMCI and ADD patients than in control participants and that MD, RD and AxD differ also between the patients and controls. These observations support our first hypothesis of more heterogenous tissue microstructure in disease states than in cognitively normal aged controls in the medial temporal lobe structures. We also showed that quantitative MRI involving T2 relaxometry and DTI indices of the hippocampus and EC is better able to detect aMCI and ADD clinical states of the disease than the measurement of the respective volumes, and that their combination is superior to do so, in support to the second and third hypotheses. The finding that quantitative MRI of the hippocampus and EC is able to detect disease states implies that the MRI modalities chosen may indicate pathology associated with early ADD.

AD pathology is characterised by the appearance of amyloid β4 plaques and neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau. Although almost always present in the brain at some level, these are found at very much higher levels in ADD, and are associated with cell death and eventual atrophy (20). To what extent amyloid and/or tau pathology are causal of AD symptoms remains a topic of research and debate (31,32). Nonetheless, it is thought that the pathology of ADD develops (or begins to develop) very much sooner than clinical presentation or widespread neuronal cell death. AD pathology is generally first seen in the hippocampus and EC, before eventual spread through the medial temporal lobe and cortices (20,33). AD pathology is evident in the brains of majority of MCI patients (34).

Both T2 relaxation time and DTI indices are descriptions of the heterogeneity of brain tissue. DTI indices have been used in assessment of hippocampal microstructure and microenvironment and shown to have ability to detect ADD-related pathology (9,11). The studies have shown decreased FA (11) and increased MD (9,11) in the body of hippocampus and these changes correlate with cognitive scores (9,11). In the current cohorts, elevated MD was observed. The previous studies (9,11) did not report sensitivity or specificity for FA or MD to separate controls from patients, however. The novelty of the current study includes quantification of tissue volume with fraction of high T2 relaxation time volume in hippocampal subfields indicative of a compromised functional state, parallel to the use of tissue type-specific T2. Our T2 MRI approach is much different from that used in previously, where T2 determined either in the whole hippocampus (18) or in ROIs within it (17,19,35) has been examined for its ability to separate cognitively healthy participants from either MCI (35) or ADD (18,19) patients with variable success. T2, as measured by a dual-echo spin echo sequence, has been reported to be either normal (17) or prolonged (18) in the hippocampus in ADD. T2 by a CPMG sequence has been found to be longer in the tail of right hippocampus in MCI (35) as well as in the head and the tail of right hippocampus in ADD (19,35) than in controls. We used a CPMG sequence and observed no difference in average hippocampal T2 times between controls, aMCI and ADD patients. Instead, Burr distributions of hippocampal subfield T2s were wider in both aMCI and ADD patients than in controls.

Our findings from quantitative MRI metrics amount to the hippocampus and EC being more heterogeneous environments at a sub-voxel level in the progression to aMCI (and further to ADD), independently of the tissue quantity. A heterogeneous tissue environment has the implication that the cell count and/or viability are unlikely to be the same as in a healthy state. Water motility and quantity, implying the presence of structures impeding its motion or creating magnetic inhomogeneities (such as myelin sheaths and iron deposits) are unlikely to be the same in the aMCI and ADD states relative to controls. The increased presence of high-T2 voxels in the aMCI and ADD patients imply more water (fewer cells) or more mobile water (fewer barriers to water, such as cell membranes and dendrites). Macroscopic partial volume effects by CSF can be discounted, since the group-wise regionalisation shows no high-T2 effects at hippocampal boundaries with surrounding CSF. The tissue heterogeneity, assessed by quantitative MRI, may therefore assess whether the tissue has entered a neurodegenerative state, in which tissue exists but with fewer intact cells per unit volume.

Quantitative MRI markers of tissue heterogeneity were not strongly correlated with tissue volumes. This agrees with a previous study where no correlation with hippocampal volume and T2 was observed in ADD (35). Volume and heterogeneity may be considered near-independent descriptors of a tissue, as hypothesised. The two categories of observations also had different group differences, volumes changing “step-wise” with group (control > aMCI > ADD), whilst tissue heterogeneity by any marker was significantly greater for aMCI and ADD than controls, but similar between aMCI and ADD. If aMCI commonly precedes the ADD state, this implies that increased tissue heterogeneity may precede volume loss. It has been reported that AD pathology is a very common finding in hippocampi of aMCI patients (34). The interpretation is that a neurodegenerative state precedes cell death – and, as hypothesised, may be detectable by MRI examination of tissue state by relaxometric and diffusion imaging of the hippocampus and EC (2). It is also interesting to note that the group differences in tissue heterogeneity markers, where measurable with subfield-specificity, show the largest effects in the EC, which is one of the earliest regions to be affected by AD pathology according to Braak staging (20). Histological examination of our participants at the time of scanning is impossible, but the correlation with known Braak staging is striking.

EC has been implicated to very early AD by animal and human work using MRI of cerebral blood volume (CBV) (36). Neuropathological analyses of neuronal loss have shown cell death in CA1 (68%), subiculum (47%) and hilus (25%) in ADD patients (37). The loss of CA1 neurons is more severe in advanced than a mild ADD (38). Growing body of MRI data indicate that in MCI hippocampal atrophy is focal localising to CA1 and subiculum (39). Some studies report also more wide spread atrophy in MCI involving also CA3 and DG (39). It has been proposed, based on hippocampal shape analyses, that those MCI patients with atrophy of multiple subfields have heightened risk of conversion to ADD (40). Regarding EC, Khan et al. (36) studied mice harbouring APP-tau transgene as well as a human cohort that was followed for 3.5 years for cognitive status. They reported selective dysfunction in participants converting to MCI in EC and parahippocampal gyrus, but not in the hippocampus. The drop in CBV was more pronounced in lateral EC compared to medial EC, indicating selective dysfunction of this structure in MCI converters, followed by a spread to precuneus and frontal brain (36). Reduced CBV was also evident in APP-tau transgenic mice, suggestive to involvement of these neurotoxic proteins in EC dysfunction. In the current study, we observed atrophy of multiple hippocampal subfields in aMCI patients, including CA1, DG, subiculum, consistent with conclusion drawn in a recent review (39). Instead, no atrophy in EC was observed by us. We found no difference in either subfield or total hippocampal volumes between aMCI and ADD patients. Instead, the volume of EC was smaller in ADD than in MCI patients.

Quantitative MRI data acquisition protocols are part of modern clinical MRI systems, for instance all MRI vendors provide clinical DTI and relaxometry sequence packages. Quantitative MRI protocols typically take 5-10 minutes longer to run than standard protocols for weighted images. Many of the image processing steps can be accomplished using free software, such as T2 fitting and hippocampal subfield segmentation. The ASHS procedure provider currently offers template atlases for healthy young and old adults, as well as aMCI patients. For other patient groups, such as ADD, sites may have to create their own atlases for use with ASHS. In-house programming is required for fitting the hippocampal subfield and EC T2 distributions, determining high-T2 fraction and their distributions in given structures. Our experience is that the described MRI protocol for hippocampal volumetry and tissue characterisation can be translated to clinical environment with modest efforts.

Our study has certain limitations. First, cohorts of participants are imbalanced for their sizes, as the aMCI and ADD patients constituted only 39% of the total participant cohort. Both aMCI and ADD have complex neuropathology involving brain structures also outside medial temporal lobe regions studied here. However, hippocampus is affected in nearly 90% of ADD patients (8). Second, the study is cross-sectional. MR image characteristics and cognitive performance change with time, both of which could be determined by follow-up examinations.

In conclusion, these data from modest cohorts of aMCI and ADD patients suggest that quantitative MRI could be better targeted to become a more sensitive marker of early ADD. We think this is an important area for future study to ensure cost effective improvement in early diagnosis of ADD such that interventions can be given at the right time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust (R385_1114), BRACE Charity, Alzheimer’s Research UK. Bryony McCann, Serena Dillon and Demitra Tsivos assisted in MRI scanning, participant recruitment and cognitive testing.

References

- 1.Coupe P, Fonov VS, Bernard C, et al. Detection of Alzheimer's disease signature in MR images seven years before conversion to dementia: Toward an early individual prognosis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(12):4758–4770. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S, Smailagic N, Hyde C, et al. 11C-PIB-PET for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;(7):CD010386. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010386.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye R, Hu Y, Yao A, et al. Impact of renin-angiotensin system-targeting antihypertensive drugs on treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(6):674–681. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, et al. Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer's disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med. 2014;275(3):251–283. doi: 10.1111/joim.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotech. 2014;32(1):40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitwell JL, Dickson DW, Murray ME, et al. Neuroimaging correlates of pathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):868–877. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70200-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palesi F, Vitali P, Chiarati P, et al. DTI and MR volumetry of hippocampus-PC/PCC circuit: In search of early micro- and macrostructural signs of Alzheimers's disease. Neurol Res Int. 2012;2012:517876. doi: 10.1155/2012/517876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK DoH, editor. Excellence) NNIoC. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong YJ, Yoon B, Lim SC, et al. Microstructural changes in the hippocampus and posterior cingulate in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(7):1215–1221. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight M, Wood B, Kauppinen R, Coulthard EJ. Magnetic resonance imaging to detect early molecular and cellular changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selnes P, Aarsland D, Bjornerud A, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging surpasses cerebrospinal fluid as predictor of cognitive decline and medial temporal lobe atrophy in subjective cognitive impairment and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(3):723–736. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agosta F, Pievani M, Sala S, et al. White matter damage in Alzheimer disease and its relationship to gray matter atrophy. Radiology. 2011;258(3):853–863. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selnes P, Fjell AM, Gjerstad L, et al. White matter imaging changes in subjective and mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(5 Suppl):S112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo Z, Zhuang X, Kumar D, et al. The correlation of hippocampal T2-mapping with neuropsychology test in patients with Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campeau NG, Petersen RC, Felmlee JP, O'Brien PC, Jack CR., Jr Hippocampal transverse relaxation times in patients with Alzheimer disease. Radiology. 1997;205(1):197–201. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.1.9314985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Yuan H, Shu L, Xie J, Zhang D. Prolongation of T2 relaxation times of hippocampus and amygdala in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2004;363(2):150–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laakso MP, Partanen K, Soininen H, et al. MR T2 relaxometry in Alzheimer's disease and age-associated memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17(4):535–540. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer's related-changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(11):1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005-2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(4):266–273. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31824b211b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia - meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psych Scand. 2009;119:252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E, Tangelos EG. Aging, memory, and mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9 Suppl 1:65–69. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares FC, de Oliveira TC, de Macedo LD, et al. CANTAB object recognition and language tests to detect aging cognitive decline: an exploratory comparative study. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:37–48. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S68186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, et al. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(6):1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinberg DA, Moeller S, Smith SM, et al. Multiplexed echo planar imaging for sub-second whole brain FMRI and fast diffusion imaging. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20(1):45–57. doi: 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, et al. Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(1):258–287. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrup K. The case for rejecting the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Nat Neurosci. 2015:794–799. doi: 10.1038/nn.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and 'wingmen'. Nat Neurosci. 2015:800–806. doi: 10.1038/nn.4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Al-Sarraj S, et al. Staging of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Brain Pathol. 2008;18(4):484–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology. 2005;64(5):834–841. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152982.47274.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pitkanen A, Laakso M, Kalviainen R, et al. Severity of hippocampal atrophy correlates with the prolongation of MRI T2 relaxation time in temporal lobe epilepsy but not in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1724–1730. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan UA, Liu L, Provenzano FA, et al. Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(2):304–311. doi: 10.1038/nn.3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West MJ, Coleman PD, Flood DG, Troncoso JC. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1994;344(8925):769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price JL, Ko AI, Wade MJ, Tsou SK, McKeel DW, Morris JC. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(9):1395–1402. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Flores R, La Joie R, Chetelat G. Structural imaging of hippocampal subfields in healthy aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2015;309:29–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costafreda SG, Dinov ID, Tu Z, et al. Automated hippocampal shape analysis predicts the onset of dementia in mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2011;56(1):212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.