Abstract

Background and Aims

E-cigarettes have the potential either to decrease or increase health inequalities depending on socioeconomic differences in their use and effectiveness. This paper estimated the associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and e-cigarette use and examined whether these associations changed between 2014 and 2017.

Design

A monthly repeat cross-sectional household survey of adults (16+) between January 2014 and December 2017. This time period was chosen given that the prevalence of e-cigarette use stabilised in England in late 2013.

Setting

The general population in England.

Participants

Participants in the Smoking Toolkit Study, a monthly household survey of smoking and smoking cessation among adults (n = 81,063; mean age 48.4 years, 49% were women) in England. Subsets included past year smokers (n = 16,232; mean age 42.8, 46% women), smokers during a quit attempt (n = 5305, mean age 40.6, 49% women), and long-term ex-smokers (n = 13,562, mean age 59.3, 44% women).

Measurements

The outcome measure for the analyses was current e-cigarette use. We also included smokers during a quit attempt where use of an e-cigarette during the most recent quit attempt was the outcome measure. Social grade based on occupation was the SES explanatory variable, using the National Readership Survey classification system of AB (Higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional), C1 (Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional), C2 (Skilled manual workers), D (Semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers), and E (State pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only). The analyses were stratified by year to assess the changes in these associations over time.

Findings

Among past-year smokers, lower SES groups had lower overall odds of e-cigarette use compared with the highest SES group AB (D: OR=0⋅53, 95% CI 0⋅40-0⋅71; E: 0⋅67, 0⋅50-0⋅89). These differences in e-cigarette use reduced over time. The use of e-cigarettes during a quit attempt showed no clear temporal or socio-economic patterns. Among long-term ex-smokers, use of e-cigarettes increased from 2014-2017 among all groups and use was more likely in SES groups C2 (2⋅03, 1⋅08-3⋅96) and D (2.29, 1⋅13-4⋅70) compared with AB.

Conclusions

From 2014-2017 in England, e-cigarette use was greater among smokers from higher compared with lower SES groups, but this difference attenuated over time. Use during a quit attempt was similar across SES groups. Use by long-term ex-smokers increased over time among all groups and was consistently more common in lower SES groups.

Funding: Cancer Research UK (C1417/A22962)

Introduction

Tobacco smoking leads to the premature death of an estimated 7 million people globally and 96,000 in the UK each year.1,2 The burden of mortality and disease is heaviest among more disadvantaged groups with smoking one of the most important causes of health inequalities.3,4 Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have rapidly become the most popular cessation devices in several high-income countries including the USA and UK,5–7 and are associated temporally with population-level improvements in success rates of cessation attempts.8,9 However, restrictions on sales and marketing vary by country. Laws in Norway, Singapore and Australia severely restrict e-cigarette availability and diverge from those in the UK and USA where it is legal to sell e-cigarettes to adults,10 of importance because the benefits of the devices for smoking cessation may be dependent on the regulatory environment.11

In England e-cigarettes are available for purchase from vaping shops, pharmacies and other retail outlets. Cancer Research UK estimate that in general the cost of cigarette smoking is twice that of using e-cigarettes.12 Since May 2016 e-cigarette advertisements are prohibited on TV, radio, online and in printed publications under article 20(5) of the European Union Tobacco Products Directive.13 Consistent with the diffusion of innovation model,14 limited data has suggested that awareness and use of e-cigarettes appeared greater among more advantaged ‘early adopter’ groups during the period in which the devices first became popular.15,16 E-cigarette use appears to have stabilised in England,17 and it is important to assess the extent to which the socioeconomic profile of e-cigarette users in England has changed across this period.

Behavioural support and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can increase the likelihood of smoking cessation, but their long term quit rates are low18–20 and may not appeal to all smokers. Unlike conventional NRT, e-cigarettes mirror the sensory and behavioural aspects of smoking and as such may provide an easier route to smoking cessation for some smokers.21 Results from recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that e-cigarettes increase the chances of smoking cessation.22–24 Some population studies at the individual-level have found a negative association or no association between e-cigarette use in the past and likelihood of smoking cessation.7,25 However, frequency of use or type of e-cigarette, known to be important mediators of quitting, were not considered in these studies.26 The RCT data are supported by population level data which show that e-cigarettes have been positively associated with the success rates of quit attempts.9 Despite growing evidence that the devices may confer benefit to smoking cessation and population health,8,27 there remain concerns regarding the uptake of e-cigarettes by young people.28 Others have argued that the concerns may be disproportionate to risks suggested by current evidence.29 Further research in this area is needed.

Health inequalities are present worldwide in countries irrespective of low, middle or high income status. Life expectancy and the possibility of living a healthy life are strongly related to the material, social, political and cultural conditions in which individuals and families live.30 Although overall smoking prevalence in England is declining (currently estimated to be 14⋅9%,31 there is higher prevalence among disadvantaged socioeconomic groups (23⋅5%) compared with more affluent groups (12⋅0%).

Considering that e-cigarettes are the most common type of support used in a smoking quit attempt, they offer a potentially useful tool to reduce smoking prevalence across the social spectrum.32 However, as with numerous other tobacco control interventions there remains the possibility that they widen inequalities in smoking33 due to greater adoption of the technology among ‘early adopters’ from more affluent socioeconomic groups who may then achieve higher rates of smoking cessation.

There is limited data on the use of e-cigarettes split by socioeconomic group at the population level. Furthermore, since e-cigarettes have the potential to either decrease or increase existing inequalities in tobacco smoking, it is important to assess their use and any associated trends across different socioeconomic groups. With recent public health policy in England showing support for the use of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation and harm reduction tool34,35 it will be useful to examine changes in use in the context of this policy environment.

Using data collected between 2014 and 2017, the aims of this current study were to i) examine whether there are associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and current e-cigarette use, ii) examine whether associations between SES and current e-cigarette use vary annually from 2014 to 2017, iii) repeat the analyses using current e-cigarette use redefined for those reporting daily and weekly e-cigarette use and iv) repeat the analyses using housing tenure as an alternative measure of SES.

Methods

Design

This study followed a repeated cross-sectional survey design and used annual data collected between January 2014 and December 2017 (comprising four full years) from the Smoking Toolkit Study (STS),36 a large nationally representative survey of smoking and smoking cessation in England. The 2014-2017 time window represents an up-to-date period since e-cigarette use stabilised in England in late 2013.

The analytic sample consisted of adults aged 16+ living in households in England. The STS involves monthly cross-sectional household computer-assisted interviews of 1700-1800 adults aged 16+ in England, conducted by the market research company Ipsos MORI. Sampling of participants for the baseline survey uses a hybrid of random probability and simple quota sampling.36 Given the high number of randomly sampled output areas included in each wave, which are themselves randomly sampled from over 170,000 initial output areas, it is unlikely that there are substantial clusters resulting in bias.

All cases were weighted using the rim (marginal) weighting technique, an iterative sequence of weighting adjustments whereby separate nationally representative target profiles are set and the process repeated until all variables match the specified targets.

Measures

Main outcomes

The three sub-groups of past-year smokers, quit attempters and long-term ex-smokers were selected because of their relevance to patterns of e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use among current and former smokers in the population.37

Responses to the question “Smoked in past-year” identified whether respondents were past-year smokers. Those who selected the answer option “Yes” were classified as past-year smokers.

Responses to the question “Whether tried to quit in past-year” identified respondents attempting to quit. Those who selected the answer option “Yes” were classified as quit attempters.

Responses to the question “Smoking status” identified respondents who are long-term ex-smokers. Those who selected the answer option “Stopped >1y ago” were classified as long-term ex-smokers.

The outcome variable of current e-cigarette use was derived from answers of ‘Electronic cigarette’ to the following questions:

“Can I check, are you using any of the following?”;

“Whether using products to help cut down the amount smoked”;

“Whether use products to cut-down, stop smoking or for any other”;

“Whether regularly use e-cigarettes in situations where NOT allowed to”.

E-cigarette use during a quit attempt was derived from an answer of ‘Electronic cigarette’ to the following question: “What used to try to help stop smoking during the most recent serious quit attempt”.

Explanatory variables

In the main analyses respondents were stratified by SES using the National Readership Survey (NRS) classification system for social grade based on occupation of the chief income earner, which has useful discriminatory power as a target group indicator.38 The NRS classification system comprises levels AB (Higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional), C1 (Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional), C2 (Skilled manual workers), D (Semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers), E (State pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only). In the sensitivity analysis, housing tenure classification39 comprised the collapsed groups ‘Social housing’ (local authority or housing association) and ‘Other’ (mortgage bought, owned outright, private renting and other).

Covariates

Additional respondent characteristics including sex, age and region were also measured using the STS.

Analysis

The analysis plan was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) https://osf.io/8zdgy/. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.1. All scripts and relevant STS variables were saved for replication.

To assess the trends in the associations between SES and current e-cigarette use (a binary outcome), logistic regression models were constructed to include social grade operationalised as the socioeconomic explanatory variable (five categories with AB as the referent) and year, and the interaction terms. Social grade was treated as a discrete unordered predictor variable rather than an ordinal predictor variable because differences between categories of social grade based on occupation are inconsistent (see above classification).

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (adjusted for age, sex, and region) were reported. To examine the interaction between social grade and year, the associations between social grade and e-cigarette outcomes were reported stratified by year.

Our analyses are reported in four tables:

Current e-cigarette use among all adults by social grade (5 categories with AB referent)

Current e-cigarette use among past-year smokers by social grade (5 categories with AB referent).

E-cigarette use during a quit attempt among smokers by social grade (5 categories with AB referent)

Current e-cigarette use among long-term ex-smokers by social grade (5 categories with AB referent)

In sensitivity analyses, analyses were repeated with current use redefined to i) those reporting daily e-cigarette use and ii) those reporting at least weekly e-cigarette use. Further sensitivity analyses were run using housing tenure39 as an alternative measure of SES, (two categories: Social housing and ‘Other’ (referent)).

Role of funding source: CRUK provided support to RW, JB, LS and LK (C1417/A22962) The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing or the decision to submit the paper for publication. LK confirms that he had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

A weighted total of 81,063 individuals completed the baseline survey between January 2014 and December 2017 (inclusive); see Table 1 for an overview of the sample characteristics. The long-term (>1-year) ex-smokers had stopped smoking for a mean of 20.5 and median 25 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of sample (weighted data).

| Variables | All adults n (%) | Past-year smokers, n (%) | Quit attempt n (%) | Long term ex-smokers n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette use* |

||||

| Yes | 4450 (5.5%) | 3460 (21.3%) | 1833 (34.6%) | 801 (5.9%) |

| No | 76613 (94.5%) | 12772 (78.7%) | 3472 (65.4%) | 12761 (94.1%) |

| Sex |

||||

| Men | 40986 (49.0%) | 8615 (53.1%) | 2707 (51.0%) | 7204 (53.1%) |

| Women | 40054 (51.0%) | 7615 (46.9%) | 2598 (49.0%) | 6355 (46.9%) |

| Age |

||||

| 16-24 | 11612 (14.3%) | 2931 (18.1%) | 978 (18.4%) | 357 (2.6%) |

| 25-34 | 13571 (16.7%) | 3617 (22.2%) | 1350 (25.4%) | 1271 (9.4%) |

| 35-44 | 13430 (16.6%) | 2990 (18.4%) | 1067 (20.1%) | 1929 (14.2%) |

| 45-54 | 14073 (17.4%) | 2968 (18.3%) | 932 (17.6%) | 2411 (17.8%) |

| 55-64 | 11370 (14.0%) | 2028 (12.5%) | 580 (10.9%) | 2522 (18.6%) |

| 65+ | 17006 (21.0%) | 1698 (10.5%) | 398 (7.5%) | 5070 (37.4%) |

|

SES group |

||||

| AB | 21938 (27.1%) | 2445 (15.1%) | 920 (17.3%) | 4358 (32.1%) |

| C1 | 22300 (27.5%) | 3932 (24.2%) | 1352 (25.5%) | 3711 (27.4%) |

| C2 | 17675 (21.8%) | 4182 (25.8%) | 1327 (25.0%) | 3066 (22.6%) |

| D | 12189 (15.0%) | 3309 (20.4%) | 970 (18.3%) | 1543 (11.4%) |

| E | 6960 (8.6%) | 2364 (14.6%) | 736 (13.9%) | 885 (6.5%) |

Ns are weighted.

E-cigarette use is defined as current use for all adults, past-year smokers and long term ex-smokers. For the quit attempt subset, e-cigarette use was defined as using an electronic cigarette during the most recent quit attempt.

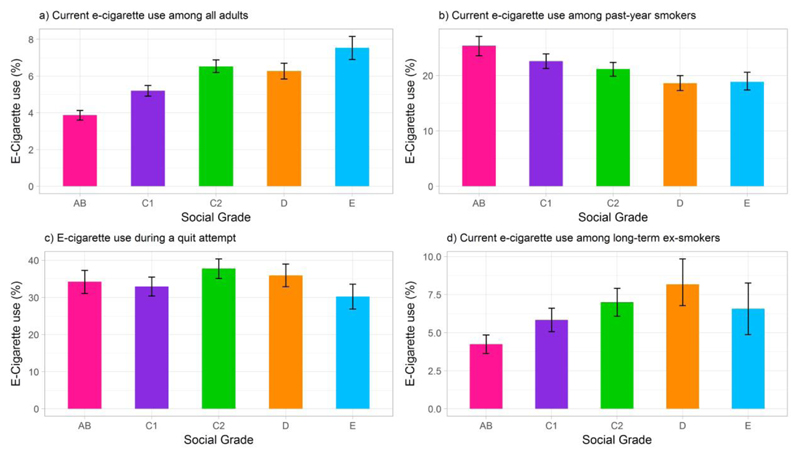

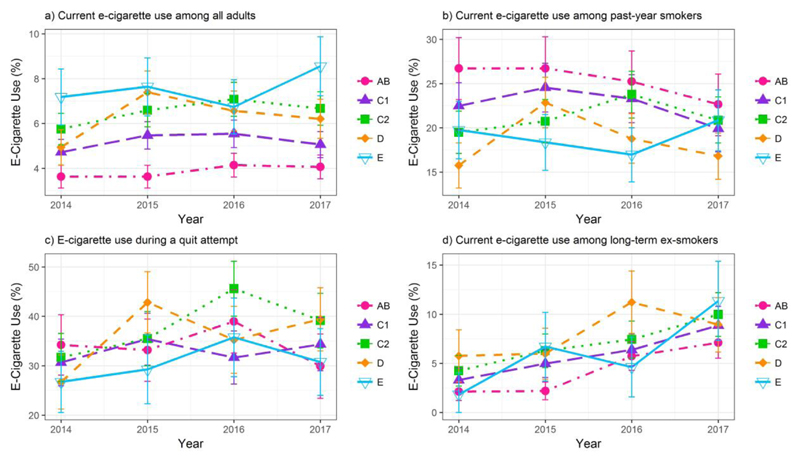

Weighted e-cigarette prevalence statistics for the four groups of interest are shown for the overall time period in Figure 1 (a-d), and for each year (From 2014 to 2017 in Figure 2 (a-d).

Figure 1. a-d: Overall prevalence of e-cigarette use in England by social grade (all years 2014-2017, weighted data).

Long term ex-smokers refers to individuals who stopped smoking >1 year ago. Social grades: AB=Higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional, C1=Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional, C2=Skilled manual workers, D=Semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, E=State pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only.

Figure 2. a-d: Prevalence of e-cigarette use in England 2014 to 2017 by social grade (weighted data).

Long term ex-smokers refers to individuals who stopped smoking >1 year ago. Social grades: AB=Higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional, C1=Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional, C2=Skilled manual workers, D=Semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, E=State pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only.

All adults

Across the overall period, there was a social gradient in the prevalence of e-cigarette use with adults from social grade E twice as likely to use an e-cigarette compared with those from AB (Table 2). There was no time trend across all social grades and little interaction between social grade and time. The exception was that prevalence in D compared with AB depended on year, with higher comparative prevalence in 2015 compared with 2014 (Supplementary Table s1 and Figure 2a). When stratified by year, the odds of e-cigarette use were greater in lower social grades compared with AB in each year (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of e-cigarette use in England among all adults 2014-2017 stratified by SES group.

| Overall (N=81057) |

2014 (N=20192) |

2015 (N=20034) |

2016 (N=20436) |

2017 (N=20395) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SES group |

|||||

| AB (N=18966) ref |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

| C1 (N=25570) |

1·36* (1·11-1·68) |

1·38* (1·12-1·71) |

1·47** (1·20-1·80) |

1·43** (1·19-1·72) |

1·36** (1·14-1·64) |

| C2 (N=16193) |

1·66*** (1·34-2·07) |

1·69*** (1·36-2·10) |

1·78*** (1·45-2·21) |

1·77*** (1·46-2·15) |

1·78*** (1·47-2·17) |

| D (N=11958) |

1·45* (1·14-1·84) |

1·48* (1·16-1·88) |

2·17*** (1·74-2·69) |

1·77*** (1·43-2·19) |

1·70*** (1·37-2·12) |

| E (N=8370) |

2·23*** (1·75-2·84) |

2·28*** (1·78-2·91) |

2·12*** (1·68-2·67) |

1·84*** (1·45-2·32) |

2·61*** (2·08-3·28) |

Ns are not weighted. Results for prevlance of e-cigarette use are presented as Odds Ratios (95% CI) against the indicated referent. <0·05 p values are indicated in bold· *p<0·01, **p<0·001, ***p<0.0001.

Past-year smokers

A social gradient in prevalence of e-cigarette use among past-year smokers was also evident for the overall time period but in the opposite direction with significantly lower odds of use by social grades C2, D and E compared with AB (Table 3). There was no time trend across all social grades and little interaction between social grade and time. The exception again was that prevalence in D compared with AB depended on year, with higher comparative prevalence in 2015 compared with 2014 (Supplementary Table s2 and Figure 2b). When stratified by year, prevalence across the social gradient was largely similar by 2017.

Table 3. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among past-year smokers in England 2014-2017 stratified SES group.

| Overall (N=16104) |

2014 (N=4252) |

2015 (N=4201) |

2016 (N=3967) |

2017 (N=3684) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SES group |

|||||

| AB (N=2063) ref |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

| C1 (N=4437) |

0·83 (0·64-1·07) |

0·83 (0·65-1·08) |

0·90 (0·70-1·16) |

0·96 (0·75-1·23) |

0·88 (0·68-1·13) |

| C2 (N=3712) |

0·70* (0·54-0·91) |

0·70* (0·54-0·91) |

0·72 (0·56-0·94) |

0·92 (0·72-1·19) |

0·91 (0·69-1·19) |

| D (N=3144) |

0·53*** (0·40-0·71) |

0·53*** (0·49-0·70) |

0·85 (0·66-1·11) |

0·70 (0·53-0·93) |

0·71 (0·53-0·96) |

| E (N=2775) |

0·67* (0·50-0·89) |

0·67* (0·50-0·89) |

0·57*** (0·43-0·75) |

0·64* (0·48-0·85) |

0·91 (0·68-1·22) |

Ns are not weighted. Results for prevlance of e-cigarette use are presented as Odds Ratios (95% CI) against the indicated referent. <0·05 p values are indicated in bold· *p<0·01, **p<0·001, ***p<0.0001.

During a quit attempt among smokers attempting to quit

There were no significant associations across the overall period between social grades and prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers attempting to quit (Table 4). There was no time trend across all social grades and little interaction between social grade and time. Though, as with past-year smokers, prevalence in D compared with AB depended on year, with higher comparative prevalence in 2015 compared with 2014 (Supplementary Table s3 and Figure 2c). When stratified by year, there remained no significant associations between social grades and prevalence of e-cigarette use.

Table 4. Prevalence of e-cigarette use during a quit attempt among smokers attempting to quit in England 2014-2017 stratified by SES group.

| Overall (N=5176) |

2014 (N=1503) |

2015 (N=1305) |

2016 (N=1156) |

2017 (N=1212) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SES group |

|||||

| AB (N=748) ref |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

| C1 (N=1501) |

0.89 (0.61-1.31) |

0.89 (0.60-1.31) |

1.03 (0.70-1.52) |

0.71 (0.48-1.04) |

1.08 (0.73-1.59) |

| C2 (N=1178) |

0.91 (0.62-1.35) |

0.89 (0.60-1.32) |

1.03 (0.69-1.56) |

1.19 (0.81-1.75) |

1.30 (0.87-1.95) |

| D (N=911) |

0.76 0.50-1.16) |

0.77 (0.50-1.17) |

1.36 (0.90-2.05) |

0.74 (0.48-1.15) |

1.40 (0.91-2.16) |

| E (N=838) |

0.76 (0.50-1.17) |

0.76 (0.49-1.18) |

0.73 (0.47-1.13) |

0.85 (0.54-1.32) |

0.95 (0.61-1.49) |

Ns are not weighted. Results for prevlance of e-cigarette use are presented as ORs (95% CI) against the indicated referent. <0·05 p values are indicated in bold. *p<0·01, **p<0·001, ***p<0.0001.

Long term ex-smokers

Across the overall period, a social gradient in the prevalence of e-cigarette use was evident among long term ex-smokers, with respondents from social grades C2 and D twice as likely to use e-cigarettes compared with AB (Table 5). There was a trend across time whereby in 2016 and 2017 respondents from all social grades were more likely to use e-cigarettes than in 2014 (Supplementary Table s4 and Figure 2d). There were no interactions between social grade and time. When stratified by year, the social gradient remained; respondents from social grades C2-E in 2015 were each almost three times as likely to use e-cigarettes compared with those from AB. Trends across all social grades were similar, with use among long-term ex-smokers increasing from 2014 to 2017 (Figure 2d).

Table 5. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among long term ex-smokers in England 2014-2017 stratified by SES group.

| Overall (N=13782) |

2014 (N=3170) |

2015 (N=3462) |

2016 (N=3533) |

2017 (N=3617) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SES group |

|||||

| AB (N=3952) ref |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

1.00 - |

| C1 (N=4301) |

1·38 (0·74-2·66) |

1·37 (0·74-2·67) |

1·77 (1·05-3·08) |

1·23 (0·84-1·81) |

1·28 (0·91-1·81) |

| C2 (N=2886) |

2·03 (1·08-3·96) |

2·07 (1·10-4·06) |

2·83** (1·66-4·97) |

1·27 (0·83-1·95) |

1·50 (1·03-2·19) |

| D (N=1541) |

2·29 (1·13-4·70) |

2·35 (1·15-4·86) |

2·92** (1·57-5·48) |

2·14** (1·36-3·35) |

1·34 (0·85-2·10) |

| E (N=1102) |

1·14 (0·37-3·03) |

1·14 (0·36-3·06) |

2·87* (1·48-5·56) |

0·81 (0·38-1·58) |

1·90 (1·14-3·07) |

Ns are not weighted. Results for prevlance of e-cigarette use are presented as ORs (95% CI) against the indicated referent. <0·05 p values are indicated in bold. *p<0·01, **p<0·001, ***p<0.0001.

Sensitivity analyses

Using housing tenure as an alternative measure of SES yielded a similar pattern of results to the main analysis. Among all adults, respondents of social housing tenure had twice the odds of using an e-cigarette overall and in each year 2014 to 2017 (Supplementary Table s5). There were largely no significant differences in prevalence of e-cigarette use between tenure groups among past-year smokers, the one exception being that when stratified by year, respondents in 2017 from social housing were more likely to use an e-cigarette. There were no significant differences in e-cigarette use during a quit attempt among smokers attempting to quit both overall and in each year. Among long-term ex-smokers, social housing respondents were twice as likely to use an e-cigarette. However, when stratified by year the associations were weaker and non-significant in 2016 and 2017.

Current e-cigarette use was redefined in further sensitivity analyses as those respondents reporting i) daily or ii) at least weekly e-cigarette use. As for the main analysis, among all adults prevalence of daily use followed a social gradient whereby odds of using e-cigarettes were significantly higher for respondents from lower social grades (Supplementary Table s6). Although less pronounced, the pattern in daily e-cigarette use among past-year smokers corresponded to the main analysis wherein respondents from lower social grades were less likely to use an e-cigarette (Supplementary Table s7). As for the main analysis, daily use of e-cigarettes during a quit attempt followed no obvious socioeconomic or temporal pattern (Supplementary Table s8). Long term ex-smokers from lower social grades were more likely to use an e-cigarette daily compared with those from AB (Supplementary Table s9), and similar to the main analysis the odds of daily e-cigarette use among long-term ex-smokers across all social grades were greater in 2016 and 2017 compared with 2014.

When current use was redefined to at least weekly use, overall prevalence of e-cigarette use among all adults also appeared to run along a social gradient with respondents from lower social grades more likely to use e-cigarettes (Supplementary Table s10). When stratified by year these differences were largely absent by 2017. No clear pattern in weekly e-cigarette us was evident overall among past-year smokers although when stratified by year respondents from lower social grades had lower odds of use in 2017 (Supplementary Table s11). Overall, no significant differences in prevalence of weekly e-cigarette use between social grades were present among smokers attempting to quit (Supplementary Table s12) and long term ex-smokers (Supplementary Table s13).

Discussion

From 2014 to 2017 in England, e-cigarette use was more prevalent among adults from lower compared with higher social grades. This gradient reflects substantially higher rates of smoking among lower social grades,5 and the higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers.16 Within past-year smokers, the social gradient was reversed with e-cigarette use more prevalent among those from higher compared with lower social grades. However, there was convergence such that use among past year smokers was similar across all social grades by 2017. E-cigarette use specifically during a quit attempt was similar across social grades throughout the period of 2014 to 2017. The use of e-cigarettes by long-term ex-smokers increased over time among all groups and was consistently more common in lower social grades. Recent US National Health Interview Survey data suggested that more educated smokers were more likely to transition to exclusive e-cigarette use than less educated smokers.40 In addition, data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study suggested that exclusive e-cigarette use was more likely among higher-income smokers.41 Conversely, this current paper found that long term ex-smokers from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups were more likely to use e-cigarettes compared with more affluent groups. This difference may be influenced by the more favourable health policy and advocacy environment towards e-cigarettes in England compared with the US. However, these comparisons are made with caution, given the different social and demographic contexts and the fact that sub-groups were defined differently. For example, exclusive use in the US study likely included a sizeable proportion of ex-smokers who had stopped within the last year. Also in the US, a recent study with an adolescent cohort found that higher SES was associated with greater exposure to e-cigarette advertising.42 However, the associations between SES and e-cigarette advertising in the UK are not well understood.

In this current paper, the social gradient evident in the use of e-cigarettes by past-year smokers between 2014 and 2017 supports previous research which found that among current smokers, e-cigarette use was associated with higher SES.16 However, in the current study there was convergence such that differences were no longer evident among past-year smokers by 2017. There has been no overall reduction in tobacco smoking inequalities in recent years,43 and as such it is unlikely that this has had an impact on the observed attenuation in e-cigarette use across the social gradient. Nonetheless, this convergence suggests that the distribution in current use of e-cigarettes by past-year smokers is unlikely to have a persistent impact on heath inequalities.

Use of e-cigarettes specifically during a quit attempt was similar across all social grades throughout the period suggesting that e-cigarette use in this group will not widen health inequalities. Differences in use may have had important implications for health inequalities because previous analyses using STS data found that changes in the overall use of e-cigarettes in England was positively associated with the success rates of quit attempts.9

Among long-term ex-smokers, a social gradient was evident with respondents from lower social grades being more likely to use e-cigarettes compared with the highest social grade. A likely explanation for this apparent gradient is that long-term ex-smokers from more affluent groups are using e-cigarettes either during a quit attempt or following smoking cessation but are then discontinuing their use, while ex-smokers from less advantaged groups continue to use e-cigarettes. Use across all social grades increased significantly between 2014 and 2017 and the increase was greatest among lower social grades. The impact that this gradient will have on inequalities depends on whether e-cigarette use by long-term ex-smokers has a protective effect against relapse, for which there is currently an absence of evidence. Insofar as it is protective, it is likely to have a positive effect on inequalities. Insofar that is has little effect on long-term relapse it may exacerbate inequalities because the use of e-cigarettes is not without risk.44 These results indicate that attention to long-term ex-smokers as a specific sub-group is important and appears to show significant patterning across SES.

Strengths of this study include that it used a large representative sample of the population and to our knowledge is the first to conduct an up-to-date and detailed analysis on the use of e-cigarettes by socioeconomic groups at the population level. Another strength is the use of a different indicator of SES in a sensitivity analysis which provided convergent results. However, as is common for this type of analysis, the results are limited by the use of cross-sectional survey data where data were self-reported and smoking status was not biochemically verified. Past e-cigarette use was not included as an outcome because the STS does not currently collect date to this end; only current and recent (<12 month) use in a quit attempt were assessed. It is also difficult to measure e-cigarette consumption levels accurately since no validated quantifiable measure is currently available. However, further sensitivity analyses using different measures of ‘current’ e-cigarette use were conducted which largely confirmed findings from the main analyses.

Further monitoring of trends is necessary in the context of the continuous evolution of e-cigarette technologies, variable media coverage and changing positions of different health and medical bodies.34,35 Future research could examine how past e-cigarette use varies among long term ex-smokers across the social gradient. Furthermore, and to the extent that e-cigarettes are effective in aiding smoking cessation, future mixed methods research is needed to investigate and explain how the success of quit attempts among those who use e-cigarettes in a quit attempt compares across different SES groups.

In conclusion, this study found that from 2014 to 2017 in England, overall e-cigarette use was more prevalent among smokers from higher compared with lower SES groups, but that this difference attenuated over time. E-cigarette use specifically during a quit attempt was similar across SES groups throughout the period. A social gradient is also evident among long-term ex-smokers with e-cigarette use consistently more likely among lower SES groups, and use increased across all groups since 2014.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Clive Bates for an enquiry and exchange about e-cigarette use and socioeconomic profile in the STS. This exchange led to the research questions for this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB, LS, LK and RW contributed to the concept and design of the study. LK prepared and statistically analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. JB, LS and RW provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. JB, LS and RW were involved in the acquisition of data and obtained funding for the study. LK is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: LS has received honoraria for talks, an unrestricted research grant and travel expenses to attend meetings and workshops by pharmaceutical companies that make smoking cessation products (Pfizer, Johnson&Johnson). RW undertakes consultancy and research for and receives travel funds and hospitality from manufacturers of smoking cessation medications. JB has received unrestricted research funding from Pfizer.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. WHO | Tobacco. WHO; 2017. [Accessed November 23, 2017]. Published http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Action on Smoking and Health. Fact Sheets - Action on Smoking and Health. [Accessed November 23, 2017];2016 Published http://ash.org.uk/category/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/

- 3.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, Lopez AD. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet. 2006;368(9533):367–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Karvonen S, Lahelma E. Socioeconomic status and smoking. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(3):262–269. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West R, Brown J, Beard E. Latest Statistics - Smoking In England. [Accessed December 6, 2017];2017 Published 2017 http://www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics/

- 6.Caraballo RS, Shafer PR, Patel D, Davis KC, McAfee TA. Preventing Chronic Disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;14 doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160600. 160600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu S-H, Zhuang Y-L, Wong S, Cummins SE, Tedeschi GJ. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. BMJ. 2017;358:j3262. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.J3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association between electronic cigarette use and changes in quit attempts, success of quit attempts, use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, and use of stop smoking services in England: time series analysis of population trends. BMJ. 2016;354:i4645. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.I4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann-Boyce J, Begh R, Aveyard P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. BMJ. 2018;360:j5543. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.J5543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong H-H, Hitchman SC, Cummings KM, et al. Does the Regulatory Environment for E-Cigarettes Influence the Effectiveness of E-Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation?: Longitudinal Findings From the ITC Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(11):1268–1276. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Research UK. E-cigarettes. [Accessed July 31, 2018];2017 Published https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/smoking-and-cancer/e-cigarettes#References_e_cig_cost0.

- 13.Dept. of Health and Social Care. Guidance: Article 20(5), Tobacco Products Directive: restrictions on advertising electronic cigarettes. [Accessed July 31, 2018];2016 Published https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/proposals-for-uk-law-on-the-advertising-of-e-cigarettes/publishing-20-may-not-yet-complete.

- 14.Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th (fifth) 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, Gilmore A, Petticrew M. E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob Control. 2016 Dec; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown J, West R, Beard E, Michie S, Shahab L, McNeill A. Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: Findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addict Behav. 2014;39(6):1120–1125. doi: 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown J, West R. Latest Trends on Smoking in England from the Smoking Toolkit Study. London: 2018. www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. In: Lindson-Hawley N, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2017;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3. CD001292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stead LF, Carroll AJ, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. In: Stead LF, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Vol. 3. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. CD001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajek P, Etter J-F, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, McRobbie H. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2013;382(9905):1629–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, et al. EffiCiency and Safety of an eLectronic cigAreTte (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066317. e66317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead LF, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. In: Hartmann-Boyce J, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grana RA, Popova L, Ling PM. A Longitudinal Analysis of Electronic Cigarette Use and Smoking Cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):812. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J, Robson D, McNeill A. Associations Between E-Cigarette Type, Frequency of Use, and Quitting Smoking: Findings From a Longitudinal Online Panel Survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1187–1194. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuang Y-L, Cummins SE, Sun JY, Zhu S-H. Long-term e-cigarette use and smoking cessation: a longitudinal study with US population. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 1):i90–i95. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.East K, Hitchman SC, Bakolis I, et al. The Association Between Smoking and Electronic Cigarette Use in a Cohort of Young People. J Adolesc Health. 2018;0(0) doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozlowski LT, Warner KE. Adolescents and e-cigarettes: Objects of concern may appear larger than they are. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;174:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul Niblett. Statistics on Smoking - England, 2018 - NHS Digital. [Accessed August 9, 2018];2018 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2018.

- 32.Mcneill A, Ls B, Calder R, Sc H. E-cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England. [Accessed November 3, 2017];2015 www.gov.uk/phe.

- 33.Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mcneill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Evidence Review of E-Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products 2018 A Report Commissioned by Public Health England. London: 2018. [Accessed April 13, 2018]. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/684963/Evidence_review_of_e-cigarettes_and_heated_tobacco_products_ 2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction. RCP London; London: 2016. [Accessed April 13, 2018]. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fidler JA, Shahab L, West O, et al. “The smoking toolkit study”: a national study of smoking and smoking cessation in England. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:479. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy DT, Cummings KM, Villanti AC, et al. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. Addiction. 2017;112(1):8–17. doi: 10.1111/add.13394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NRS. National Readership Survey. Social Grade. [Accessed November 24, 2017];2017 Published http://www.nrs.co.uk/nrs-print/lifestyle-and-classification-data/social-grade/

- 39.Department for Communities and Local Government. GOV.UK; 2017. [Accessed December 6, 2017]. English Housing Survey: guidance and methodology. Published https://www.gov.uk/guidance/english-housing-survey-guidance-and-methodology#about-the-english-housing-survey. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman AS, Horn SJL. Socioeconomic Disparities in Electronic Cigarette Use and Transitions from Smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Jun; doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harlow AF, Stokes A, Brooks DR. Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Differences in E-Cigarette Uptake Among Cigarette Smokers: Longitudinal Analysis of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Jul; doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon P, Camenga DR, Morean ME, et al. Socioeconomic status and adolescent e-cigarette use: The mediating role of e-cigarette advertisement exposure. Prev Med (Baltim) 2018;112:193–198. doi: 10.1016/J.YPMED.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith C, Hill S, Amos A. REFERENCE AUTHORS. [Accessed August 5, 2018]; http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/

- 44.Stephens WE. Comparing the cancer potencies of emissions from vapourised nicotine products including e-cigarettes with those of tobacco smoke. Tob Control. 2017;27(1):10–17. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.