Abstract

HIV sero-status disclosure among people living with HIV (PLWH) is an important component of preventing HIV transmission to sexual partners. Due to various social, structural, and behavioral challenges, however, many HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients do not disclose their HIV status to all sexual partners. In this analysis, we therefore examined non-disclosure practices and correlates of non-disclosure among high-risk HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals. HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals who reported HIV-risk behaviors were enrolled (N=133) and assessed for HIV disclosure, risk behaviors, health status, antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, HIV stigma, social support and other characteristics. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify significant correlates of non-disclosure. Overall, 23% reported not disclosing their HIV status to sexual partners, who also had high levels of HIV risk: sharing of injection equipment (70.5%) and inconsistent condom use (93.5%). Independent correlates of HIV non-disclosure included: being virally suppressed (aOR=0.19, p=0.04), high HIV-related stigma (aOR=2.37, p=0.03), and having multiple sex partners (aOR=5.87, p=0.04). Furthermore, a significant interaction between HIVrelated stigma and living with family/friends suggests that those living with family/friends were more likely to report not disclosing their HIV status when higher levels of perceived stigma was present. Our findings support the need for future interventions to better address the impact of perceived stigma and HIV disclosure as it relates to risk behaviors among opioid-dependents patients in substance abuse treatment settings.

Keywords: Non-disclosure, people living with HIV, opioid-dependent, HIV-related stigma, HIV risk behavior

1. Introduction

HIV sero-status disclosure to sexual partners is an important component of HIV prevention and treatment efforts because it facilitates informed decision-making before sexual contact (Lan, Li, Lin, Feng, & Ji, 2016; Przybyla et al., 2013). Improvements in the health and longevity of people living with HIV (PLWH), due to advances in medical science, may have important implications for both individual and public health outcomes (Lan et al., 2016; Shacham, Small, Onen, Stamm, & Overton, 2012). Disclosing HIV status to sexual partners has been generally linked to safer drug- and sex-related practices (e.g., consistent condom use, lower frequency of drug use) (Crepaz & Marks, 2003; Li, Luo, Rogers, Lee, & Tuan, 2017; Parsons et al., 2005) and reduction in HIV transmission (Pinkerton & Galletly, 2007; Przybyla et al., 2013; Shacham et al., 2012). In recent decades, increased attention to transmission within sero-discordant couples has highlighted the potential role of disclosure as a way to encourage prevention approaches including the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and HIV treatment-as-prevention (TasP) (Brooks et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2011; Do et al., 2010). Furthermore, disclosure can also help PLWH garner better social support, reduce psychological distress, and encourage them to access comprehensive medical care and support services (Li et al., 2017; Smith, Rossetto, & Peterson, 2008; Zang, He, & Liu, 2015).

Despite its many potential benefits, disclosing one’s HIV-positive status may have unintended negative consequences, like conflict with a partner, elevated stigma, depression, lack of social support, breach of confidentiality, rejection, and even violence, and therefore place significant burdens on PLWH (Brown, Serovich, & Kimberly, 2016; Calin, Green, Hetherton, & Brook, 2007; Daskalopoulou, Lampe, Sherr, Phillips, Johnson, Gilson, Perry, Wilkins, Lascar, Collins, Hart, Speakman, Rodger, et al., 2017; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2013; Maman, Groves, Reyes, & Moodley, 2016; Przybyla et al., 2013; Vyavaharkar et al., 2011; Wolitski, Pals, Kidder, Courtenay-Quirk, & Holtgrave, 2009). Due to individual and societal attitudes towards HIV and the possible negative consequences, disclosure is a sensitive issue and is often difficult to negotiate for many PLWH. For HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals – a group of people who use drugs (PWUD) – who are often socially marginalized, it may involve an even more complex decision-making process (Go et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Parsons, VanOra, Missildine, Purcell, & Gomez, 2004). Given the complexities surrounding HIV disclosure, they may be reluctant to disclose their HIV status and avoid disclosure altogether.

The decision to not disclose one’s HIV status (i.e., non-disclosure) is multifaceted and influenced by structural, relational, and personal considerations. In the broader literature, several factors have been associated with non-disclosure (Adeniyi et al., 2017; Ahn, Bailey, Malyuta, Volokha, & Thorne, 2016; Daskalopoulou, Lampe, Sherr, Phillips, Johnson, Gilson, Perry, Wilkins, Lascar, Collins, Hart, Speakman, & Rodger, 2017; Elford, Ibrahim, Bukutu, & Anderson, 2008; Jasseron et al., 2013; Overstreet, Earnshaw, Kalichman, & Quinn, 2013). Despite significant research in this area, prior studies have not systematically investigated non-disclosure practices, nor have they explored theoretically informed correlates among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients within drug treatment settings. An evidence-based understanding of the scope of non-disclosure can inform future interventions specifically tailored for this population. In this paper, we therefore sought to explore the factors associated with non-disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and procedures

The data reported here are derived from the baseline assessment of the Holistic Health for HIV (3H+) project, a randomized controlled trial to improve HIV risk reduction and medication adherence among high-risk HIV-infected opioid-depenent patients. The study design and procedures of the parent study has been previously described (Shrestha & Copenhaver, 2018; Shrestha, Karki, Huedo-Medina, & Copenhaver, 2016; Shrestha, Krishnan, Altice, & Copenhaver, 2015). Briefly, participants were recruited from community-based addiction treatment programs and HIV clinical care settings within the greater New Haven, Connecticut. Participants were recruited through clinic-based advertisements and flyers, word-of-mouth, and direct referral from counselors. Screening was conducted by trained research assistants either by phone or private room. Individuals who met inclusion criteria and expressed interest in participating provided informed written consent and were administered a baseline assessment. All participants were reimbursed for the time and effort needed to participate in the survey.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Connecticut and Yale University, and received board approval from APT Foundation. Clinical trial registration was completed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01741311).

2.2. Participants

Between September 2012 and January 2018, 133 HIV-infected, opioid-dependent individuals were recruited. Additional inclusion criteria included: 1) being 18 years or older; 2) reporting drug- or sex-related risk behavior (past 6 months); 3) being able to understand, speak, and read English; and 4) not actively suicidal, homicidal, or psychotic.

2.3. Measures

Participants were assessed using an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). Measures included socio-demographic characteristics, health status, HIV-related stigma, drug-and sex-related risk behaviors, and sero-status non-disclosure. Key measures are described below.

The dependent variable was non-disclosure of HIV status, which was defined as having any sex without disclosure of HIV-positive status to the partners in the past six months. Sero-status non-disclosure to partners was measured as “yes”/”no” by asking, “In the past six months, did you have sex with anyone that you did not tell your HIV status sometime before you had sex?”

Health status variables including length of time since HIV diagnosis, whether the participant was currently taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), and baseline viral load (VL) and CD4 count were abstracted from their medical record. Adherence to ART in the past month was assessed using a empirically validated, self-report visual analog scale (VAS) approach (Giordano, Guzman, Clark, Charlebois, & Bangsberg, 2004). Using standardized cut-off, adherence of 95% or greater was considered optimal adherence (Paterson et al., 2000). Viral suppression was defined as clinic-recorded HIV-1 RNA test value <200 copies/mL and high CD4 count (≥500 cells/mL) (Bowen et al., 2017; Crepaz, Tang, Marks, & Hall, 2017).

Measures related to the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model constructs associated with HIV risk reduction (Huedo-Medina, Shrestha, & Copenhaver, 2016) included: (a) Information – HIV risk-related knowledge (range: 0 – 4); (b) Motivation - readiness to change and intentions to change HIV risk behavior (range: 0 – 32); and (c) Behavioral Skills - risk reduction skills (range: 0 – 16).

HIV-related stigma was measured using a validated 24-item HIV stigma scale (Earnshaw, Smith, Chaudoir, Amico, & Copenhaver, 2013) with items rated on 5-point Likert-type scales with higher scores indicating greater stigma. Items were averaged to create a composite score (α=0.93).

The HIV risk assessment, adapted from NIDA’s Risk Behavior Assessment (Dowling-Guyer et al., 1994) was used to measure several aspects of HIV risk behaviors in the past 30 days, including a measurement of “any” high risk behavior (sexual or drug-related) as well as measurements of event-level (i.e., partner-by-partner) behaviors.

2.4. Data analyses

Covariates included in the analysis were based on prior research as well as findings from other studies conducted within drug treatment settings. We computed descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. We conducted bivariate analyses for significant associations with the dependent variable (i.e., non-disclosure of HIV status). Additionally, we included the interaction term (variables from the main effects model), one at a time, in the model containing all the main effects to determine the interactive effect on non-disclosure. We then conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses on bivariate associations found to be significant at p<0.10. Stepwise forward entry and backward elimination methods both showed the same results in examining the independent correlates (p<0.05) expressed as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and their 95% confidence intervals. Model fit was assessed using a Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (Hosmer, Hosmer, Le Cessie, & Lemeshow, 1997). Collinearity between variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Estimates were evaluated for statistical significance based on p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., 2015).

3. Results

The baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 49.3 (±8.3), and 41.4% were living with family/friends. The mean duration of HIV diagnosis was 14.1 (±9.6) years and were maintained on a stable methadone dose (Mean: 64.5 mg). Of 121 (91.0%) individuals who were taking ART, 57.9% had achieved optimal adherence and 80.4% had a high CD4 count. HIV-related stigma scores ranged from 1.0 to 4.4, with a mean score of 2.0 (±0.7). Self-reported HIV risk behaviors were highly prevalent among study samples. Almost half of the participants (46.6%) reported to have injected illicit drugs in the past 30 days. Of those, 58.1% reported having shared injection equipment. Similarly, 21.1% of the participants reported having sex with more than one sexual partner and only 14.3% reported to have always used condoms with their sexual partners in the past 30 days (Figure 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of participants and HIV transmission risk behaviors, stratified by non-disclosure of HIV status

| Variables | Entire Sample (N = 133) |

Non-Disclosure of HIV Status |

OR g (95% CI h) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | No (n = 102) | Yes (n = 31) | |||

| Characteristics of participants | |||||

| Age: Mean (±SD) a | 49.3 (±8.3) | 50.4 (7.6) | 45.4 (9.5) | 0.932 (0.887, 0.979) | 0.005 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 78 (58.6) | 62 (46.6) | 16 (12.0) | - | - |

| Female | 55 (41.4) | 40 (30.1) | 15 (11.3) | 1.453 (0.647, 3.263) | 0.365 |

| Heterosexual sexual orientation | |||||

| No | 102 (76.7) | 15 (11.3) | 11 (8.3) | - | - |

| Yes | 31 (23.3) | 87 (65.4) | 20 (15.0) | 0.313 (0.125, 0.785) | 0.013 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| YesNon-white | 95 (71.4) | 75 (56.4) | 20 (15.0) | - | - |

| YesWhite | 38 (28.6) | 27 (20.3) | 11 (8.3) | 1.528 (0.648, 3.600) | 0.333 |

| Currently married | |||||

| No | 118 (88.7) | 91 (68.4) | 27 (20.3) | - | - |

| Yes | 15 (11.3) | 11 (8.3) | 4 (3.0) | 1.226 (0.361, 4.161) | 0.744 |

| High school graduate | |||||

| No | 60 (45.1) | 44 (33.1) | 16 (12.0) | - | - |

| Yes | 73 (54.9) | 58 (43.6) | 15 (11.3) | 0.711 (0.318, 1.592) | 0.407 |

| Employed | |||||

| No | 127 (95.5) | 97 (72.9) | 30 (22.6) | - | - |

| Yes | 6 (4.5) | 5 (3.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0.647 (0.073, 5.753) | 0.696 |

| Income level | |||||

| < $10,000 | 113 (85.0) | 86 (64.7) | 27 (20.3) | - | - |

| ≥ $10,000 | 20 (15.0) | 16 (12.0) | 4 (3.0) | 0.796 (0.245, 2.586) | 0.705 |

| Living with family/friends | |||||

| No | 78 (58.6) | 57 (42.9) | 21 (15.8) | - | - |

| Yes | 55 (41.4) | 45 (33.8) | 10 (7.5) | 0.603 (0.258, 1.409) | 0.068 |

| Methadone dose: Mean (±SD) a | 64.5 (±39.1) a | 66.7 (38.6) | 56.2 (40.5) | 0.993 (0.982, 1.004) | 0.218 |

| HIV diagnosis duration (Years): Mean (±SD) a | 14.1 (±9.6) | 14.8 (9.8) | 11.9 (8.6) | 0.968 (0.927, 1.011) | 0.094 |

| Taking ART b | |||||

| No | 12 (9.0) | 8 (6.0) | 4 (3.0) | - | - |

| Yes | 121 (91.0) | 94 (70.7) | 27 (20.3) | 0.574 (0.161, 2.054) | 0.394 |

| Optimal ART adherence c | n = 121 | ||||

| No | 44 (33.1) | 36 (29.8) | 8 (6.6) | - | - |

| Yes | 77 (57.9) | 58 (47.9) | 19 (15.7) | 1.474 (0.585, 3.717) | 0.411 |

| Virally suppressed d | n = 112 | ||||

| No | 22 (19.6) | 14 (12.5) | 8 (7.1) | - | - |

| Yes | 90 (80.4) | 73 (65.2) | 17 (15.2) | 0.408 (0.147, 1.126) | 0.083 |

| High CD4 count e | n = 114 | ||||

| No | 55 (48.2) | 44 (38.6) | 11 (9.6) | - | - |

| Yes | 59 (51.8) | 45 (39.5) | 14 (12.3) | 1.244 (0.510, 3.038) | 0.631 |

| HIV risk reduction related | |||||

| Information: Mean (±SD) | 3.1 (±0.7) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.759 (0.431, 1.337) | 0.340 |

| Motivation: Mean (±SD) | 27.4 (±4.0) | 27.3 (4.1) | 27.6 (4.1) | 1.016 (0.919, 1.123) | 0.756 |

| Behavioral skills: Mean (±SD) | 9.8 (±3.8) | 10.0 (3.7) | 9.5 (4.3) | 0.968 (0.873, 1.074) | 0.542 |

| HIV-related Stigma: Mean (±SD) | 2.0 (±0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.7) | 1.429 (0.835, 2.445) | 0.093 |

| Duration of drug use: Mean (±SD) | 24.7 (±9.7) | 25.7 (9.5) | 21.3 (9.6) | 0.952 (0.910, 1.395) | 0.129 |

| Knowledge of partner’s HIV status | |||||

| No | 80 (60.2) | 29 (28.4) | 20 (19.6) | - | - |

| Yes | 53 (39.8) | 46 (45.1) | 7 (6.9) | 0.221 (0.083, 0.587) | 0.002 |

|

HIV transmission risk behaviors | |||||

| Ever injected illicit drug | |||||

| No | 15 (11.3) | 10 (7.5) | 5 (3.8) | - | - |

| Yes | 118 (88.7) | 92 (69.2) | 26 (19.5) | 0.565 (0.177, 1.800) | 0.334 |

| Injected illicit drug (past 30 days) f | n = 118 | ||||

| No | 56 (47.5) | 48 (40.7) | 12 (10.2) | - | - |

| Yes | 62 (52.5) | 44 (37.3) | 14 (11.9) | 1.273 (0.532, 3.047) | 0.588 |

| Shared injection equipment f | n = 62 | ||||

| No | 26 (41.9) | 21 (33.9) | 5 (8.1) | - | - |

| Yes | 36 (58.1) | 24 (38.7) | 12 (19.4) | 2.100 (0.635, 6.947) | 0.224 |

| Multiple sex partner f | |||||

| No | 105 (78.9) | 90 (67.7) | 15 (11.3) | - | - |

| Yes | 28 (21.1) | 12 (9.0) | 16 (12.0) | 8.000 (3.166, 20.212) | <0.001 |

| Consistent condom use f | |||||

| No | 114 (85.7) | 85 (63.9) | 29 (21.8) | - | - |

| Yes | 19 (14.3) | 17 (12.8) | 2 (1.5) | 0.345 (0.075, 1.584) | 0.171 |

SD: Standard deviation

ART: Antiretroviral therapy

Optimal ART adherence: Adherence ≥ 95%

Virally suppressed: Viral load < 200 copies/mL

Health CD4 count: CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/mm3

In the past 30 days

Odds ratio

Confidence interval

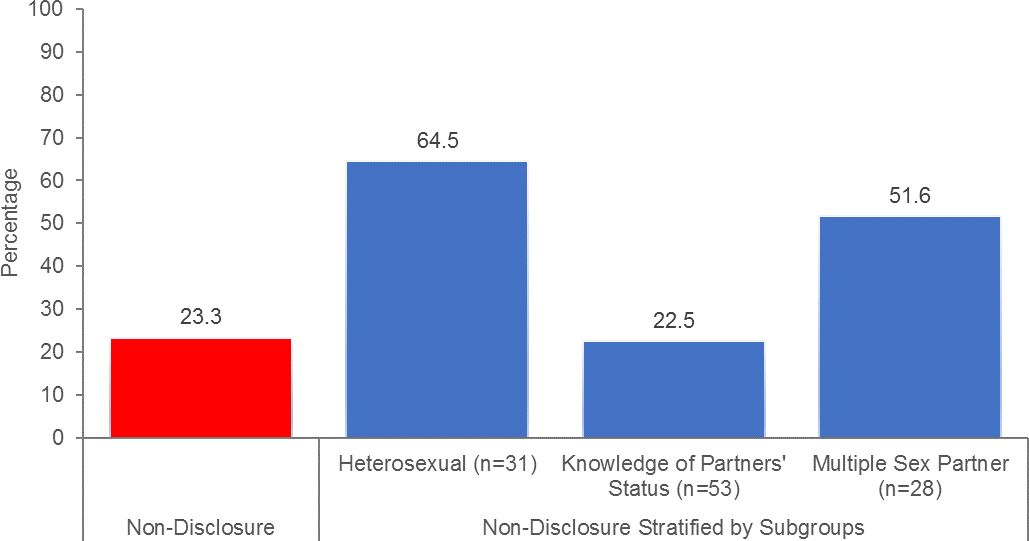

Fig. 1:

Stratified assessment of non-disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to sexual partners (N=133)

Nearly a third (23%) of the participants reported not disclosing their HIV status with a sexual partner, whereas, 39.8% of them reported to know their sexual partner’s HIV status. Table 1 describes the bivariate comparisons of those reporting nondisclosure. Of note, there was significant difference based on participants’ knowledge of sexual partner’s HIV status (p=0.002) and whether they had multiple sex partner (p<0.001), which is portrayed in Figure 1. Other factors in bivariate analysis associated with non-disclosure were being older (p=0.005) and heterosexual (p=0.013).

Table 2 shows the independent correlates associated with HIV-positive status non-disclosure. Participants who were virally suppressed were less likely to withhold disclosing their HIV status to sexual partners (aOR=0.189, p=0.041). Whereas, participants with a higher degree of perceived HIV-related stigma (aOR=2.366, p=0.032) and having multiple sex partners (aOR=5.868, p=0.040) were significantly more likely to not disclose their HIV status. Furthermore, we also found a significant interaction between stigma and living with family/friends on non-disclosure (aOR=7.792, p=0.020).

Table 2:

Multivariate logistic regression models of factors associated with nondisclosure of HIV status (N=133)

| Variables | Non-Disclosure of HIV Status |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR b | 95% CI c | p | |

| Age | 0.957 | 0.875, 1.046 | 0.334 |

| Heterosexual sexual orientation | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.395 | 0.109, 1.434 | 0.158 |

| Living with family/Friends | |||

| No | - | - | - |

| Yes | 0.673 | 0.244, 1.861 | 0.446 |

| HIV diagnosis duration (Years) | 1.038 | 0.967, 1.115 | 0.300 |

| Virally suppressed a | |||

| No | |||

| Yes | 0.189 | 0.038, 0.934 | 0.041 |

| HIV-related stigma | 2.366 | 1.064, 4.338 | 0.032 |

| Know partners’ HIV status | |||

| No | |||

| Yes | 0.372 | 0.079, 1.757 | 0.212 |

| Multiple sex partners | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 5.868 | 1.088, 31.634 | 0.040 |

| HIV-related stigma*Living with family/friends | 7.792 | 1.515, 14.161 | 0.020 |

|

R2 = 0.445 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test: Chi-square = 5.497; p = 0.600 | |||

Note:

Virally suppressed: Viral load < 200 copies/mL;

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio;

CI: Confidence interval

4. Discussion

Several important findings were gleaned with regard to non-disclosure practices among high-risk HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals, and these may have significant implications for future HIV prevention efforts in the clinical settings. A substantial proportion of participants in our study reported not disclosing their HIV status to any sexual partner. This finding underscored the complexities and challenges surrounding HIV sero-status disclosure among high-risk opioid-dependent patients in drug treatment settings. The higher rate of non-disclosure in our sample may be partially explained by a longstanding experience with drug use (e.g., mean duration: 24.7 years). One potential explanation is that those with longstanding drug use may have been subjected to discrimination before HIV treatment could potentially render PLWH non-infectious to others and now continue to perceive that the risk of sero-status disclosure outweighs the potential benefits (Li et al., 2017; Valle & Levy, 2009). Furthermore, the dual veils of stigma derived from both addiction and HIV creates synergistic jeopardy that reduces their willingness to disclose their status. Findings from this study support previous studies demonstrating that the HIV sero-status disclosure process is difficult and complex, especially for high-risk HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals in drug treatment.

We found that self-reported HIV risk behaviors (both drug- and sex-related) were highly prevalent among this sample, which is consistent with findings from prior studies with similar risks (Copenhaver, Lee, Margolin, Bruce, & Altice, 2011; Karki, Shrestha, Huedo-Medina, & Copenhaver, 2016; Shrestha, Altice, Karki, & Copenhaver, 2018; Shrestha et al., 2016). A significant proportion of participants reported sharing of injection equipment, having multiple sex partners, and inconsistent condom use during sexual intercourse. This is especially concerning given that they are continuing to engage in risky behaviors with most of them not disclosing their HIV status, and thus may be transmitting HIV to sero-discordant partner. These findings highlight the importance of HIV status disclosure and the need for additional evidence-based HIV prevention strategies. As such, the delivery of integrated PrEP and ART may be the most pragmatic HIV prevention strategy among HIV-serodiscordant couples (Brooks et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2011; Do et al., 2010).

In this study, the odds of non-disclosure of HIV sero-status was lower among individuals who were virally suppressed. Although being virally suppressed has been shown to prevent sexual transmission of HIV (Cohen et al., 2016), it is encouraging that these individuals report a willingness to disclose their sero-status. Feelings of responsibility and the desire to protect one’s sexual partners from potential HIV infection may have enhanced motivation to disclose their HIV status, and thereby overriding concerns about negative consequences (Parsons et al., 2004). Furthermore, we found that greater HIV-related stigma was associated with non-disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners, which is consistent with the literature on stigma and disclosure (French, Greeff, Watson, & Doak, 2015; Ojikutu et al., 2016; Ostrom, Serovich, Lim, & Mason, 2006; Overstreet et al., 2013; Przybyla et al., 2013). It is possible that negative beliefs around one’s HIV status and the associated damaging consequences may reduce the likelihood that HIV status is disclosed in a sexual context (Overstreet et al., 2013). HIV-related stigma remains a considerable barrier to ending the pandemic, necessitating effective strategies that directly provide access to information, community support, and advocacy. One strategy that has been rapidly gathering momentum in the recent years is the Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) campaign (Prevention Access Campaign, 2018; The Lancet HIV, 2017). It synthesizes scientific data from the TasP literature (Günthard, Saag, Benson, & et al., 2016; Volberding, 2017) and places PLWH as being responsible for HIV transmission by caring enough to optimally adhere to HIV medications, rendering themselves unable to transmit HIV irrespective of ongoing sexual risk. Such strategies remove the absolute need to disclose their HIV status and markedly reduces the consequences to PLWH through the disclosure process. The pro-social U=U campaign empowers PLWH so that by protecting themselves, they protect others even when HIV disclosure is not addressed.

Additionally, participants who reported having multiple sex partners were more likely to not disclose their HIV status. With multiple sex partners, the complex dynamics of relationship (Mbonye, Siu, Kiwanuka, & Seeley, 2016) may increase fears of rejection, and thus, lead to non-disclosure. Our findings further demonstrated that there is a complex interplay between HIV-related sigma, family/friend support, and nondisclosure. As an extension of prior findings, our results showed an interactive effect of stigma and living with family or friends on individuals’ non-disclosure practices. That is, those living with family/friends were more likely to report not disclosing their HIV status when faced with a higher degree of perceived stigma. Social support is an important psychological factor that can promote HIV status disclosure (Jorjoran Shushtari, Sajjadi, Forouzan, Salimi, & Dejman, 2014; Lee, Yamazaki, Harris, Harper, & Ellen, 2015), but situational variables such as HIV-related stigma may override the positive influence of social support in decisions about disclosure. This buffering incluence can help explain how disclosure practices among PLWH changes in the presence of social support and how stigma impacts long-term social support and PLWH’s willingness and/or patterns of disclosure. From a prevention standpoint, this highlights the importance of precisely targeting the impact of perceived stigma and increasing social support, while developing interventions to improve disclosure practices among HIV-infected opioid-depenent patients.

The findings from this study are not without limitations. First, the sample was drawn from individuals enrolled in MMT, potentially limiting generalizability of findings to HIV-infected opioid-dependents individuals not enrolled in the methadone program. Second, we utilized a dichotomous measure of HIV sero-status non-disclosure status obtained from a single-item question. Furthermore, we did not assess non-disclsoure status at a partner specific level. We are therefore unable to fully capture the complexity and circumstances of non-disclosure to sexual partners. Third, much of the data in this study came from self-report and is thus subject to both social desirability and recall biases. Fourth, the data in this study were cross-sectional in nature, thus limiting our ability to infer causation from the associations found. Fifth, this study included relatively small sample size which may have limited our ability to detect differences with smaller effect size. Last, the current study was focused on non-disclosure to sexual partners, potentially limiting our ability to assess HIV transmission risk through sharing of injection equipment among injecting partners. Despite these limitations, the findings from this study significantly contribute to the literature to date, in which there is little research investigating non-disclosure patterns among this underserved population.

5. Conclusions

HIV sero-status disclosure to sexual partners is an important component of HIV prevention and treatment efforts (Lan et al., 2016; Przybyla et al., 2013). Findings from this study underscore the complexities surrounding HIV sero-status nondisclosure/disclosure among high-risk HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients, as highlighted by the relatively high rates of HIV non-disclosure. Our findings are unique given the relative dearth of research on HIV non-disclosure practices and associated factors among this risk group. In the contemporary era of TasP, interventions that reduce the complexity of disclosure by reducing risks to others, like U=U, are crucial for providing the foundation for allowing the disclosure process to evolve over time. Given high prevalence of HIV status non-disclosure (23%) in this high-risk population, future interventions should consider the specific needs of the population (e.g., harm reduction, overcoming stigma, improving social support) that better address the impact of perceived stigma and HIV disclosure as it relates to risk behaviors among opioid-dependent enrolled in treatment.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for research (R01 DA032290) and for career development (K02 DA033139) to Michael Copenhaver.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Investigational Review Board (IRB) at the University of Connecticut and Yale University and received board approval from APT Foundation Inc. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Adeniyi OV, Ajayi AI, Selanto-Chairman N, Goon DT, Boon G, Fuentes YO, on behalf of the East London Prospective Cohort Study, G. (2017). Demographic, clinical and behavioural determinants of HIV serostatus non-disclosure to sex partners among HIV-infected pregnant women in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. PLoS ONE 12(8), e0181730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn JV, Bailey H, Malyuta R, Volokha A, & Thorne C (2016). Factors Associated with Non-disclosure of HIV Status in a Cohort of Childbearing HIV-Positive Women in Ukraine. AIDS and behavior 20(1), 174–183. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen EA, Canfield J, Moore S, Hines M, Hartke B, & Rademacher C (2017). Predictors of CD4 health and viral suppression outcomes for formerly homeless people living with HIV/AIDS in scattered site supportive housing. AIDS Care 29(11), 1458–1462. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1307920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, & Leibowitz AA (2011). Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIVserodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care 23(9), 1136–1145. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MJ, Serovich JM, & Kimberly JA (2016). Depressive Symptoms, Substance Use and Partner Violence Victimization Associated with HIV Disclosure Among Men Who have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav 20(1), 184–192. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1122-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calin T, Green J, Hetherton J, & Brook G (2007). Disclosure of HIV among black African men and women attending a London HIV clinic. AIDS Care 19(3), 385–391. doi: 10.1080/09540120600971224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR (2016). Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. New England Journal of Medicine 375(9), 830–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR (2011). Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine 365(6), 493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copenhaver MM, Lee IC, Margolin A, Bruce RD, & Altice FL (2011). Testing an optimized community-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk reduction and antiretroviral adherence intervention for HIV-infected injection drug users Subst Abus (Vol. 32, pp. 16–26). England. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crepaz N, & Marks G (2003). Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care 15(3), 379–387. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, & Hall HI (2017). Viral Suppression Patterns Among Persons in the United States With Diagnosed HIV Infection in 2014. Ann Intern Med 167(6), 446–447. doi: 10.7326/l17-0278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daskalopoulou M, Lampe FC, Sherr L, Phillips AN, Johnson MA, Gilson R, . . . Rodger AJ (2017). Non-Disclosure of HIV Status and Associations with Psychological Factors, ART Non-Adherence, and Viral Load Non-Suppression Among People Living with HIV in the UK. AIDS and behavior 21(1), 184–195. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daskalopoulou M, Lampe FC, Sherr L, Phillips AN, Johnson MA, Gilson R, . . . For the, A. S. G. (2017). Non-Disclosure of HIV Status and Associations with Psychological Factors, ART Non-Adherence, and Viral Load Non-Suppression Among People Living with HIV in the UK. AIDS Behav 21(1), 184–195. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do NT, Phiri K, Bussmann H, Gaolathe T, Marlink RG, & Wester CW (2010). Psychosocial factors affecting medication adherence among HIV-1 infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in Botswana. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 26(6), 685–691. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowling-Guyer S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG, Needle R, Watters J, Andersen M, . . . Tortu (1994). Reliability of Drug Users' Self-Reported HIV Risk Behaviors and Validity of Self-Reported Recent Drug Use. Assessment 1(4), 383–392. doi: 10.1177/107319119400100407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, & Copenhaver MM (2013). HIV Stigma Mechanisms and Well-Being Among PLWH: A Test of the HIV Stigma Framework. AIDS and behavior 17(5), 1785–1795. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elford J, Ibrahim F, Bukutu C, & Anderson J (2008). Disclosure of HIV status: the role of ethnicity among people living with HIV in London. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 47(4), 514–521. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318162aff5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French H, Greeff M, Watson MJ, & Doak CM (2015). HIV stigma and disclosure experiences of people living with HIV in an urban and a rural setting. AIDS Care 27(8), 1042–1046. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1020747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giordano TP, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois ED, & Bangsberg DR (2004). Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clin Trials 5. doi: 10.1310/jfxh-g3x2-eym6d6ug [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Go VF, Latkin C, Le Minh N, Frangakis C, Ha TV, Sripaipan T, . . . Quan VM (2016). Variations in the Role of Social Support on Disclosure Among Newly Diagnosed HIV-Infected People Who Inject Drugs in Vietnam. AIDS Behav 20(1), 155–164. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1063-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, & et al. (2016). Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of hiv infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the international antiviral society–usa panel. JAMA 316(2), 191–210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G 2nd, Outlaw AY, Wohl AR, Fields S, Hildalgo J, & LeGrand S (2013). Patterns of HIV disclosure and condom use among HIV-infected young racial/ethnic minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 17(1), 360–368. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0331-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, & Lemeshow S (1997). A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Statistics in medicine 16(9), 965–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huedo-Medina TB, Shrestha R, & Copenhaver M (2016). Modeling a Theory-Based Approach to Examine the Influence of Neurocognitive Impairment on HIV Risk Reduction Behaviors Among Drug Users in Treatment. AIDS and behavior 20(8), 1646–1657. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1394-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IBM Corp. (2015). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jasseron C, Mandelbrot L, Dollfus C, Trocmé N, Tubiana R, Teglas JP, . . . Warszawski J (2013). Non-Disclosure of a Pregnant Woman’s HIV Status to Her Partner is Associated with Non-Optimal Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission. AIDS and behavior 17(2), 488–497. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0084-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorjoran Shushtari Z, Sajjadi H, Forouzan AS, Salimi Y, & Dejman M (2014). Disclosure of HIV Status and Social Support Among People Living With HIV. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 16(8), e11856. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.11856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karki P, Shrestha R, Huedo-Medina TB, & Copenhaver M (2016). The Impact of Methadone Maintenance Treatment on HIV Risk Behaviors among High-Risk Injection Drug Users: A Systematic Review. Evid Based Med Public Health 2(pii: e1229). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan CW, Li L, Lin C, Feng N, & Ji G (2016). Community Disclosure by People Living With HIV in Rural China. AIDS Educ Prev 28(4), 287–298. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.4.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Yamazaki M, Harris DR, Harper GW, & Ellen J (2015). Social Support and HIV-Status Disclosure to Friends and Family: Implications for HIVPositive Youth. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 57(1), 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Luo S, Rogers B, Lee S-J, & Tuan NA (2017). HIV Disclosure and Unprotected Sex Among Vietnamese Men with a History of Drug Use. AIDS and behavior 21(9), 2634–2640. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1648-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maman S, Groves AK, Reyes HLM, & Moodley D (2016). Diagnosis and disclosure of HIV status: Implications for women’s risk of physical partner violence in the postpartum period. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 72(5), 546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mbonye M, Siu GE, Kiwanuka T, & Seeley J (2016). Relationship dynamics and sexual risk behaviour of male partners of female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res 15(2), 149–155. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1197134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojikutu BO, Pathak S, Srithanaviboonchai K, Limbada M, Friedman R, Li S, Team HIVPTN (2016). Community Cultural Norms, Stigma and Disclosure to Sexual Partners among Women Living with HIV in Thailand, Brazil and Zambia (HPTN 063). PLoS ONE 11(5), e0153600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostrom RA, Serovich JM, Lim JY, & Mason TL (2006). The role of stigma in reasons for HIV disclosure and non-disclosure to children. AIDS Care 18(1), 60–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overstreet NM, Earnshaw VA, Kalichman SC, & Quinn DM (2013). Internalized stigma and HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care 25(4), 466–471. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.720362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Bimbi DS, Wolitski RJ, Gómez CA, & Halkitis PN (2005). Consistent, inconsistent, and non-disclosure to casual sexual partners among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS 19, S87–S97. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167355.87041.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parsons JT, VanOra J, Missildine W, Purcell DW, & Gomez CA (2004). Positive and negative consequences of HIV disclosure among seropositive injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev 16(5), 459–475. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.5.459.48741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, . . . Singh N (2000). Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 133(1), 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinkerton SD, & Galletly CL (2007). Reducing HIV transmission risk by increasing serostatus disclosure: a mathematical modeling analysis. AIDS Behav 11(5), 698–705. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9187-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prevention Access Campaign. (2018). Risk of sexual transmission of HIV from a person living with HIV who has undetectable viral load. Retrieved from https://www.preventionaccess.org/consensus

- 42.Przybyla SM, Golin CE, Widman L, Grodensky CA, Earp JA, & Suchindran C (2013). Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV: Examining the roles of partner characteristics and stigma. AIDS Care 25(5), 566–572. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shacham E, Small E, Onen N, Stamm K, & Overton ET (2012). Serostatus Disclosure Among Adults with HIV in the Era of HIV Therapy. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 26(1), 29–35. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shrestha R, Altice FL, Karki P, & Copenhaver MM (2018). Integrated Bio-behavioral Approach to Improve Adherence to Pre-exposure Prophylaxis and Reduce HIV Risk in People Who Use Drugs: A Pilot Feasibility Study. AIDS and behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2099-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrestha R, & Copenhaver MM (2018). Viral suppression among HIV-infected methadone-maintained patients: The role of ongoing injection drug use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrestha R, Karki P, Huedo-Medina T, & Copenhaver M (2016). Treatment engagement moderates the effect of neurocognitive impairment on antiretroviral therapy adherence in HIV-infected drug users in treatment. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 28(1), 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shrestha R, Krishnan A, Altice FL, & Copenhaver M (2015). A noninferiority trial of an evidence-based secondary HIV prevention behavioral intervention compared to an adapted, abbreviated version: Rationale and intervention description. Contemp Clin Trials 44, 95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith R, Rossetto K, & Peterson BL (2008). A meta-analysis of disclosure of one's HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care 20(10), 1266–1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Lancet HIV. (2017). U=U taking off in 2017. The Lancet HIV 4(11), e475. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valle M, & Levy J (2009). Weighing the consequences: self-disclosure of HIVpositive status among African American injection drug users. Health Educ Behav 36(1), 155–166. doi: 10.1177/1090198108316595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volberding PA (2017). HIV Treatment and Prevention: An Overview of Recommendations From the 2016 IAS–USA Antiretroviral Guidelines Panel. Topics in Antiviral Medicine 25(1), 17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Tavakoli A, Saunders R, & Annang L (2011). HIV-disclosure, social support, and depression among HIVinfected African American women living in the rural southeastern United States. AIDS Educ Prev 23(1), 78–90. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolitski RJ, Pals SL, Kidder DP, Courtenay-Quirk C, & Holtgrave DR (2009). The Effects of HIV Stigma on Health, Disclosure of HIV Status, and Risk Behavior of Homeless and Unstably Housed Persons Living with HIV. AIDS Behav 13(6), 1222–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9455-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zang C, He X, & Liu H (2015). Selective disclosure of HIV status in egocentric support networks of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 19(1), 72–80. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0840-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]