Abstract

For individuals who are food insecure, food pantries can be a vital resource to improve access to adequate food. Access to adequate food may be conceptualized within five dimensions: availability (item variety), accessibility (e.g., hours of operation), accommodation (e.g., cultural sensitivity), affordability (costs, monetary or otherwise), and acceptability (e.g., as related to quality). This study examined the five dimensions of access in a convenience sample of 50 food pantries in the Bronx, NY. The design was cross-sectional. Qualitative data included researcher observations and field notes from unstructured interviews with pantry workers. Quantitative data included frequencies for aspects of food access, organized by the five access dimensions. Inductive analysis of quantitative and qualitative data revealed three main inter-related findings: (1) Pantries were not reliably open: only 50% of pantries were open during hours listed in an online directory (several had had prolonged or indefinite closures); (2) Even when pantries were open, all 5 access dimensions showed deficiencies (e.g., limited inventory, few hours, pre-selected handouts without consideration of preferences, opportunity costs, and inferior-quality items); (3) Open pantries frequently had insufficient food supply to meet client demand. To deal with mismatch between supply and demand, pantries developed rules for food provision. Rules could break down in cases of pantries receiving food deliveries, leading to workarounds, and in cases of compelling client need, leading to exceptions. Adherence to rules, versus implementation of workarounds and/or exceptions, was worker- and situation-dependent and, thus, unpredictable. Overall, pantry food provision was unreliable. Future research should explore clients’ perception of pantry access considering multiple access dimensions. Future research should also investigate drivers of mismatched supply and demand to create more predictable, reliable, and adequate food provision.

Keywords: Urban, Food Environment, Community Nutrition, Food pantries, Food Insecurity

INTRODUCTION

Over 15.6 million U.S. households experienced food insecurity at times during 2016.1 In other words, one or more members of the household had limited access to adequate food due to a lack of money and other resources.2 Food insecurity is tied to poverty and to poorer health among children, adults, and the elderly. Among children, food insecurity is associated with several adverse health conditions: birth defects,3 asthma,4,5 impaired cognition,6,7 behavioral and mental-health problems,5,7 and poorer general health.4,8,9 Among adults, there are associations with higher rates of smoking,10 hypertension,11 and hyperlipidemia.11 There are also associations with diabetes12,13 and poor glycemic control.14 In older adults, food insecurity is associated with depression and poor overall health.15

For many who experience food insecurity, food pantries can be a vital resource to improve access to food:16–18 Food pantries can help food-insecure individuals meet basic nutritional requirements and improve their diets and health.16,19–21 Food pantries are emergency food programs that distribute food to individuals and families in need.22 These pantries usually receive food and drink from food banks--large non-profit organizations that purchase, collect, and store foods from a variety of sources (e.g., manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and government agencies).22

Although food banks provide set standards and provide some central organization for pantries,22 food pantries themselves operate individually. As such individual pantries can make decisions about how they serve, who they serve, and to what extent individuals--food pantry clients--have access to emergency food.23 Specific operations and client eligibility criteria may vary by food-pantry location (i.e., a physical site or facility for food distribution) and, within a location, by food-pantry sessions (times of food distribution, often specifically for certain subgroups of clients). Variability in operations and eligibility can lead to differences in access to food.

In order to conceptualize access to food, a useful framework comes from the broader literature on local food sources. Reviewing that literature, Caspi and colleagues define five access dimensions,24 These dimensions might be applied to food pantries and include the following: (1) availability (the variety or selection of food items being offered), (2) accessibility (e.g., physical location and the number of hours of operation), (3) accommodation (e.g., hours relative to personal schedule, consideration of cultural preferences), (4) affordability (value and costs—even if not strictly monetary), and (5) acceptability (degree to which items meet individual standards, e.g., as related to food quality).24

Considering the five dimensions, there have been a handful of studies examining access with regard to food pantries. For instance, studies on accessibility suggest pantry locations are geographically proximal to food insecure populations,19,25 whereas studies of availability suggest limitations with regard to selection, variety, and nutritional quality.26,27 Studies of acceptability find important differences by food-distribution method; client-choice distribution (providing clients the ability to select their own items) has greater acceptability than handouts of pre-selected item assortments.28–32

However, to date the literature examining access dimensions related to food pantries is scant, and most studies have tended to focus on only a single access dimension. In order to fully characterize access for food-pantry clients, multidimensional understanding is essential. Without better understanding, those suffering from food insecurity may face challenges to food acquisition and compromised health that might otherwise be avoided.

The current study aimed to examine multiple dimension of access for food pantry clients. In particular, investigators sought to apply Caspi and colleagues’ five-dimensional framework to food pantries in two large urban areas.

METHODS

This study used both qualitative and quantitative approaches to examine access to food at pantries. The study was considered exempt by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Setting

Investigators focused on the Bronx, NY. The Bronx is the borough of New York City with the highest rates of food insecurity (31% of residents overall; 37% of children),33 and worst health outcomes in New York State.34 The study focused on the southern half of the Bronx, home to the poorest congressional district in the country,35 and a region where more than 50% of census tracts experience ‘high or extreme poverty’ (poverty rates exceeding 30 percent of individuals).35

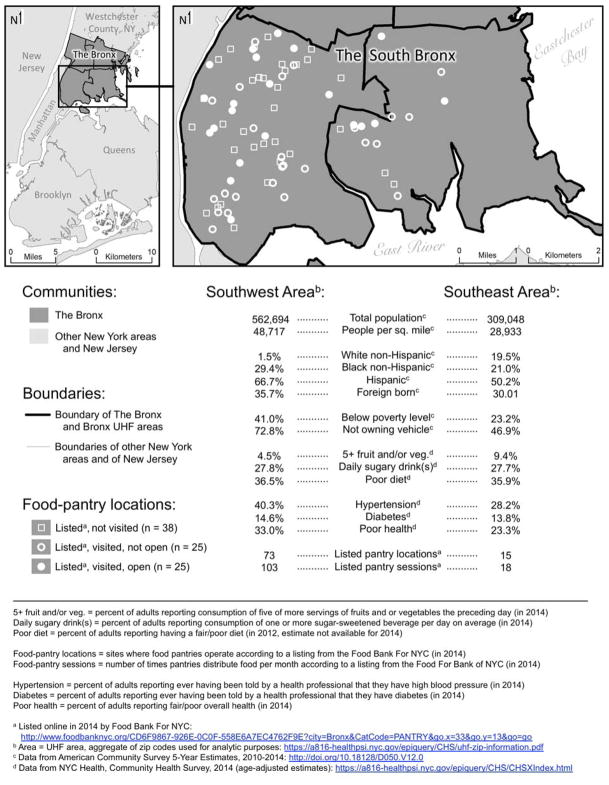

Poverty rates within the southern Bronx vary geographically,35 for instance by specific aggregates of zip codes the city uses for analytic purposes: i.e., UHF areas.36 The two UHF areas in the southern Bronx essentially split the region in half. The southwest and southeast halves differ in population density,37 socio-demographics,37 eating behaviors,38 and rates of diet-related diseases38 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the two large geographic areas of the southern Bronx, and food-pantry locations in 2014

Sample

To identify food pantries in the southwest and southeast areas of the Bronx, members of the research team used an online listing compiled by Food Bank For New York City (NYC). Food Bank For NYC is the city’s largest hunger-relief organization and a food provider for most food pantries in the city;39 its online listing was selected for size and scope.

The Food Bank’s online listing denoted two related meanings for the term ‘food pantry’: (1) a location (i.e., a physical site for food distribution) and (2) a session (i.e., a time of food distribution at a given site). Different sessions occurring at the same site--that is, different periods of food distribution at a single location--might run differently, with different procedures and client-eligibility criteria. For example, one pantry sessions might be only for the elderly, another only for those with HIV, and still another only for workers, even at a single location.

Based on locations and listed times of food distribution, investigators developed a schedule for visiting pantries. The aim was to include as many pantries as possible (over an eight-week period during which there was funding for, and availability of, fieldworkers to conduct pantry visits). Ultimately, the sample included 50 pantry locations (38 in the southwest, 12 in the southeast), hosting 80 sessions (65 in the southwest, 15 in the southeast).(Table 1)

Table 1.

Number of food-pantry locations that were listed online, visited by investigators, and open at the time of visits, as well as associated pantry sessions, southern Bronx, 2014

| Food-pantry characteristic | Listed (online by Food Bank For NYC) (n) |

Visited (by study investigators) (n) |

Open (among the food pantries visited)c (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locationsa | |||

| Overall in the southern Bronx | 88 | 50 | 25 |

| In the southwest area | 73 | 38 | 20 |

| In the southeast area | 15 | 12 | 5 |

| Associated sessionsb | |||

| Overall in the southern Bronx | 121 | 80d | 41d |

| In the southwest area | 103 | 65d | 35d |

| In the southeast area | 18 | 15d | 6d |

Locations = sites for food distribution; street addresses for food-pantry facilities

Associated sessions = times of recurring food distribution hosted at pantry locations

The reasons that visited food-pantry locations were not open as listed online appear in Table 2.

‘Visited’ and ‘open’ for pantry sessions refer to the sessions listed online as being associated with visited and open pantry locations

Data collection

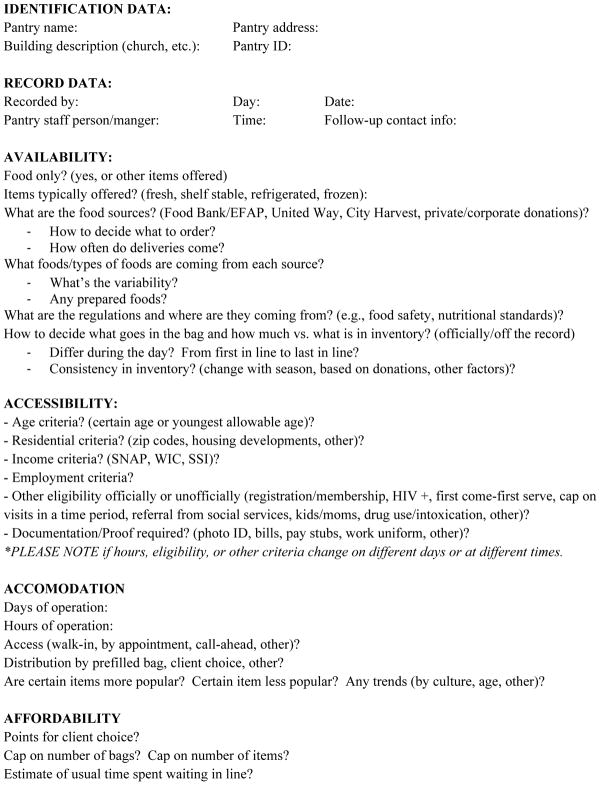

In June 2014, two fieldworkers (ZAG and HJF) made pilot visits to several pantries to inform data collection for the study. Information about pantries came from (1) making observations of pantry facilities, procedures, and offerings and (2) having conversations with pantry workers. To guide observations and to direct conversations, fieldworkers used a preliminary data-collection tool, adapted from those used to assess other local food sources in earlier food-environment research.40–45 Based on pilot observations and conversations, the preliminary data-collection tool was revised to include specific considerations unique to food pantries. For example, the final tool included items about client-eligibility criteria and distribution methods, characteristics of food pantries not applicable to other local food sources.

The final data-collection tool (Appendix - Figure 1) captured structured and semi-structured information, organized around Caspi and colleagues’ five-dimensional framework of food access. Using this tool, the research team visited pantry locations and asked about access dimensions related to pantry sessions (including sessions occurring at times other than when visits occurred). For assessments specifically about item acceptability, or quality, determinations were based on pantry-worker reports or investigator observations of item appearance (i.e., whether or not looking old, damaged, discolored, or rotten according to criteria from previously published scales46,47).

Appendix: Figure 1.

Food Pantry Data-Collection Tool

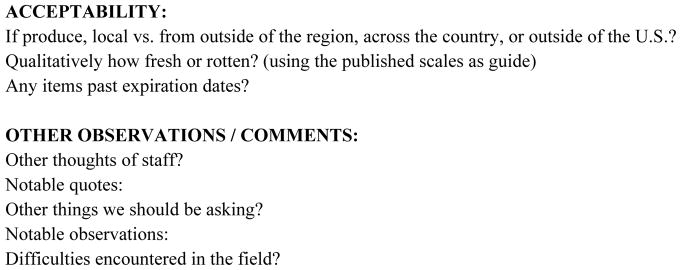

To complement structured and semi-structured items, investigators jotted unstructured observational fieldnotes.48 The areas of focus for fieldnotes were guided by published literature on food pantries,49,50 conversations with investigators who had published earlier pantry research,25,51,52 and by ongoing observations and conversations during study visits. Direct and paraphrased quotes from pantry workers were included whenever possible. Investigators also took photographs as part of data collection (Appendix - Figure 2 for examples).

Appendix: Figure 2.

Montage of images from Bronx food pantries, 2014

Top row: signs announcing pantry closures

Bottom row: guest bill of rights, eligibility/access criteria, and provider bill of rights

Pantry visits occurred from June through August 2014. If a pantry session was found not to be running as listed online by Food Bank For NYC, members of the research team attempted one more visit at another time before categorizing the pantry as ‘unable to be assessed.’ If signs posted during initial visits suggested alternative days and/or times of operation, subsequent visits were made during those hours. If there were no signs posted, fieldworkers attempted to clarify hours via pantry phone numbers listed by the Food Bank; otherwise, second visits occurred again during the days and times listed online.

Fieldworkers entered structured data into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), version 5.6.3 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).53 Unstructured and semi-structured jottings were compiled into a single Microsoft Word document.

Data analysis

For quantitative analysis of structured data items, investigators used State version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Quantitative analyses included frequencies for how often visited pantries were open, and the reasons for not being open in cases when pantries were closed. Quantitative analyses also included frequencies for aspects of access at food-pantry sessions according to five access dimensions.

For qualitative analyses, investigators included data from all open pantries, as well as data from two pantries where late pilot visits occurred. Each pantry location was assigned a unique identifier: the number of the order in which the pantry was assessed (1–27) plus an east (E) or (W) distinction (e.g., 03E, 25W). The multidisciplinary team of co-authors—with backgrounds in medical anthropology, health services research, preventive medicine, epidemiology, public health, family medicine, internal medicine, geographic information systems (GIS), and public policy—used an iterative process of reading and discussing the qualitative data to identify salient themes related to food access.54 Qualitative data were considered in the context of quantitative findings.

RESULTS

Although investigators endeavored to assess differences in pantry access by geographic area, the majority of pantry locations (83% of total) and pantry sessions (85% of total) were in the southwest area (the area with greater poverty). Moreover, even pantries that were technically in the southeast area tended to be right along the border between areas (Figure 1). This geographic reality challenged meaningful differentiation between pantries in the two geographic areas. Also, the fact that many pantries were closed when they were listed as being open precluded the inclusion of all pantries in the study and resulted in a non-random sample. As a consequence, no tests of statistical significance were performed because interpretation would be impossible. Findings below distinguish between southeast and southwest areas--as per the study’s intended aims--but these differences should be interpreted with caution.

Regarding pantries overall, an inductive analysis of quantitative and qualitative data revealed three main inter-related findings: (1) Pantries were not reliably open, (2) Even when pantries were open, access to food was restricted, (3) Open pantries frequently had insufficient food supply to meet client demand.

Pantries were not reliably open

Table 1 shows the number of food-pantry locations that were listed online, the number visited by investigators, and the number that were actually open at the time of visits.

At the time of data collection in 2014, the online Food Bank For NYC listing included 88 pantry locations (73 in the southwest, 15 in the southeast), hosting 121 sessions (103 in the southwest, 18 in the southeast). Despite visits to 50 pantry locations (57% of the total listed online) only 25 locations were actually open when they were expected to be based on the online listing. In other words, half of all pantry locations might have been closed to those seeking food—even after multiple attempts to access. Closures may have been worse in the southeast Bronx where only 42% of pantry locations (5 of 12) were open, compared to 53% (20 of 38) in the southwest. Again, however, differences between geographic areas should be interpreted with caution given the relatively small number of pantries in the southeast area, their distribution along the east-west area border, and the non-random sample.

Table 2 shows the various reasons why 50% of visited food-pantry locations were not open during scheduled hours as listed by Food Bank For NYC.

Table 2.

Reasons that visited food-pantry locations in the southern Bronx were not open as listed online, 2014a

| Pantries in the southwest area | Pantry locations (n) |

Associated sessions (n) |

Pantries in the southeast area | Pantry locations (n) |

Associated sessionsa (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed with no sign | 6 | 13 | Open different day/hours than listed by the Food Bank | 2 | 2 |

| Closed with sign noting closure for indefinite period and no other information | 2 | 2 | Closed with no sign | 1 | 1 |

| Closed with sign noting closure for weeks (2 weeks in one case, 3 weeks in another) without further explanation | 2 | 3 | Closed with sign noting closure for 5 weeks without further explanation | 1 | 1 |

| Closed with sign noting no food delivery | 2 | 5 | Closed for renovation for unspecified duration | 1 | 2 |

| Open different day/hours than listed by the Food Bank | 2 | 2 | Location not a food pantry (actually a day care) | 1 | 1 |

| Closed with sign stating last pantry day until further notice | 1 | 1 | Shut downc | 1 | 2 |

| Not opening when scheduled, with long line of people waiting (and no change hours later) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Location not a food pantry (actually a medical pavilion) | 1 | 2 | |||

| Shut downb | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 18 | 30 | Total | 7 | 9 |

Listed reasons that visited pantry locations were not open pertain to initial visits. Reasons on subsequent visits were the generally the same or similar (e.g., initially closed with sign explaining no food delivery and then subsequently closed with no sign, initially open different day/hours than listed by the Food Bank and then subsequently not opened as advertised/posted)

Confirmed by workers at a soup kitchen at the site; reason food pantry shut down not known

Per inspector for Emergency Food Assistance Program (encountered during visit to another pantry), this location was shut down by the fire department for storing food near exits

Reasons included permanent closures, temporary closures with or without signage, and incorrect or out-of-date addresses (i.e., listed location not actually a food pantry). At one pantry (15W), the location was not technically closed but the workers were waiting for a delivery and had no food to give out. At another pantry (24E) a worker said, “We just put a sign on the door when we have food and are open.” A worker at another pantry (25W) offered that state funding cuts had led multiple pantries to close.

Even when pantries are open, access to food was restricted

Table 3 shows aspects of access at food-pantry sessions. Aspects are organized by the five access dimensions.

Table 3.

Aspects of access at food-pantry sessions in the southern Bronx, 2014a

| Aspects of access at food-pantry sessions | Pantry sessions overall in the southern Bronx (n out of 41 total) |

Pantry sessions in the southwest area (n out of 35 total) |

Pantry sessions in the southeast area (n out of 6 total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access dimension: Availability | |||

| Any shelf-stable items | 41 | 35 | 6 |

| Any fresh items | 41 | 35 | 6 |

| Any refrigerated items | 34 | 32 | 2 |

| Any frozen items | 34 | 32 | 2 |

| Any prepared foodsb | 16 | 13 | 3 |

| Different items based on line positionc | 32 | 27 | 5 |

| May close within 1 hour of opening due to running out of food | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Access dimension: Accessibility | |||

| Scheduled to be open 2 hours or fewerd | 30 | 26 | 4 |

| Officially open less often than weeklye | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Will not serve those <18 years old | 23 | 21 | 2 |

| Must have documentation for accessf | 28 | 25 | 3 |

| Closed to disruptive/disrespectful persons | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Access only by appointmentg | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Access dimension: Accommodation | |||

| No weekend hours | 36 | 32 | 4 |

| No hours outside M-F, 9am–5pm | 29 | 25 | 4 |

| Pre-filled bags only (no client choice) | 22 | 17 | 5 |

| Any organic items | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Religious benth | 37 | 31 | 6 |

| Access dimension: Affordability | |||

| Long lines, with time and opportunity costsi | 37 | 31 | 6 |

| ’Client choice’ pointsj | 19 | 18 | 1 |

| Access dimension: Acceptability | |||

| Any items past expiration dates | 19 | 15 | 4 |

| Any items of inferior quality (unrelated to label dates)k | 16 | 16 | 0 |

| Any items from local farms | 10 | 10 | 0 |

For pantries sessions associated with visited pantry locations that were open

Pantries occasionally offered sandwiches, prepared hot meals, and TV dinners

Less food available towards the end of pantry sessions when offerings may be different and more restricted in terms of variety

Some pantries do not have set closing times, but rather close when they run out of food (often within an hour)

Three food-pantry sessions in the southwest occurred only every other week, despite being listed as weekly by the Food Bank. Two food-pantry sessions in the southeast occurred monthly, despite being listed as weekly by the Food Bank.

Examples: photo ID, pay stub, shelter letter, work uniform, proof of address, birth certificate, Medicaid/Medicare card

All other pantry sessions were some variation of first-come-first-serve lines

Pantries located in churches and/or operated by church members; although not necessarily discriminating based on beliefs or pushing a religious agenda, at least one pantry used food provision as a “means to an end” to proselytize for Christianity

Pantries describing long lines waiting for food with no guarantee food will last until the last person is served

‘Client Choice’ is a system like ‘shopping’ where clients can choose various item from different item categories, sometimes receiving an allotment of ‘points’ to ‘spend’ within categories and overall; items that are more desirable often ‘cost’ more points.

Quality was based on consensus among investigators (informed by published scales) or based on workers’ reports (if there were no items to view)

Availability

All pantry sessions offered shelf-stable items and at least some fresh items. About three quarters of pantry sessions were at locations having equipment to accommodate refrigerated and frozen foods (helpful for domiciled clients). Just over one third of sessions made prepared foods available (especially helpful for clients without cooking facilities). Greater details about the availability of specific food and drink products, including sizes, food groups, and nutritional quality are available in a complementary manuscript.(authors, paper under review) Client position in line mattered at nearly three quarters of pantry sessions; food pantry staff noted, “by the end of the line there’s usually less food” (13W) and “the bags are smaller” (26E). About one quarter of pantry sessions might run out of food within one hour of opening, before everyone in line was served.

Accessibility

Nearly three quarters of pantry sessions were scheduled to last two hours or fewer. However as noted, some might close within one hour of opening due to running out of food. Most pantry sessions were weekly (three pantry sessions in the southwest were every other week and one was monthly; three pantry sessions in the southeast were monthly). More than half of pantry sessions were closed to unaccompanied children. Almost three quarters had other eligibility criteria like age, residential or shelter status, employment status, or HIV status, and required documentation for access (e.g., photo ID, utility bill, shelter letter, pay stub, Medicare or Medicaid card). More than a quarter of pantry sessions were explicitly closed to those deemed disrespectful or disruptive in the judgment of pantry workers: “this program is a charity, not a right” (19W); disrespectful clients might be “suspended for a month or so” (18W). Four pantry sessions in the southwest required clients to make appointments in advance.

Accommodation

Only about a quarter of pantry sessions had weekend hours. More than three quarters of sessions occurred during the regular work day, Monday-Friday, 9am–5pm. More than half of pantry sessions distributed food using pre-filled bags, providing clients no choices to accommodate personal preferences. As an example of a personal preference, ‘organic’ items (a proxy for ‘purity/naturalness’40 valued by some lower-income consumers55) could be found at nearly a quarter of the pantry sessions in the southwest and none in the southeast. There were attempts to accommodate cultural food preferences: “we try to have dried beans and rice for Hispanic clients” (25W). Cultural accommodation also emerged related to religious tolerance. All but four pantry sessions occurred in churches and/or were operated by church members and (while Food Bank For NYC regulations prohibit the exchange of food for attendance at religious services) one pastor said explicitly that his church runs the pantry as a way to proselytize; to have people “listen to the church’s message” as a “means to an end” (24E).

Affordability

Although food items through pantries were available to clients at no monetary cost, they were not cost-free. Clients often spent hours waiting in line to access pantries. As a staff member at one pantry (16W) noted, “they begin giving tickets [for a place in line] at 10 am, but food distribution doesn’t start until 2 pm.” A worker another pantry (05W) noted that lines could start forming as early as 5 am. In addition to time costs and potential opportunity costs of waiting in line, costs nearer to those financial in nature involved ‘points’ at ‘client choice’ pantries. ‘Client choice’ is a system like ‘shopping’ where clients can choose various items from different categories, often receiving an allotment of ‘points’ to ‘spend’ within categories and overall. Nearly half of all pantry sessions operated by ‘client choice,’ with more desirable items costing more points. Other pantries used pre-filled bags, providing a handout of pre-selected items having no relation to affordability other than the opportunity costs of waiting in line or the costs of not choosing a different pantry where there may have been more food for the time invested.

Acceptability

In terms of acceptability, pantry workers perceived label dates as an indicator of quality--irrespective of the items on which dates appeared and irrespective of whether dates indicated production, sell-by, use-by, or expiration dates. Some pantry workers expressed the view that their pantries received inferior-quality products (e.g.. products having older dates) because of their location in the Bronx: “that wouldn’t happen in Manhattan” (04W); “the best food goes to the rest of the city” (20W). Items past expiration were observed at about half of all pantry sessions in both geographic areas (in all cases, the items were shelf-stable, not products where there would be any kind of safety concern as with fresh liquid milk, for instance). As for quality unrelated to label dates (i.e., whether or not items appeared old, damaged, discolored, or rotten), about half of all pantry sessions in the southwest and none in the southeast offered items deemed to be of inferior appearance by investigators and/or pantry workers. Approximately one-third of pantry sessions in the southwest and none in the southeast offered local items, that is items from local farms--a proxy for ‘freshness,’40 if not superior quality otherwise.

Open pantries frequently had insufficient food supply to meet client demand

Qualitative and quantitative data made it clear that demand for food usually exceeded supply. According to pantry workers, there were two specific times when this issue became particularly pressing: (1) at the end of the month, when money from government assistance programs tended to run out, and (2) in the summer, when children no longer received food from their schools; when grants for pantries to obtain food ended; and when Food Bank For NYC closed for inventory. At one pantry (20W), a worker noted that people might travel from other cities or even other states to access different pantries at times of exceptional need.

In order to deal with mismatched supply and demand, pantries developed rules for food provision. Qualitative analyses revealed that rules could breakdown in cases of pantries receiving food deliveries, requiring workarounds, and in cases of compelling client need, requiring exceptions (Table 4)

Table 4.

Rules, workarounds, and exceptions that emerged through observations and conversations at open food pantries, southern Bronx, 2014

| Aspect of operation | Rules (pre-planned systems for orderly operation) |

Workarounds (improvisations based on food deliveries) |

Exceptions (rule breaking to meet clients perceived needs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Who can enter |

Workers restrict number of people served

|

Impromptu provision at delivery times

|

Workers ignore restrictions on who receives food

|

| Documents for entry |

Workers require documentation for access

|

No need for documents outside of facility

|

Workers choose not to check identification

|

| Organization of the line |

Strategies for organizing the line

|

Informal access from delivery trucks

|

Workers allow needy to bypass the line

|

| Food Distribution |

Established approach for consistent dispensing of usual items

|

Improvised distribution for newly received, often perishable items

|

Workers hand out food at special times when needy people present

|

Values in parentheses = identification number of select representative pantries

Rules--or pre-planned systems for efficient, consistent, and orderly food distribution--helped structure operations and promote regularity. Pantries had rules about who received food (e.g., eligibility criteria and documentation), how they received it (e.g., client choice versus prefilled bags), and in what order (e.g., first come first served versus. by appointment). Rules were simultaneously a response to limited supply in the face of overwhelming demand and a cause, by design, of further restricted access. Although rules provided a sense of structure and regularity, they could not always accommodate the vagaries of food delivery, which necessitated workarounds.

Workarounds were improvisations in food provision at times of food deliveries. For example, if clients spotted delivery trucks arriving and crowded around as deliveries were being received, pantry workers might just hand out items right from the truck without regard to established rules pertaining to eligibility, documentation, or distribution. If deliveries included perishable items that might not last until the next pantry session--and no clients were immediately present to receive them--workers might leave those items out for anyone in the neighborhood to take. Alternatively, as at one pantry (14W), perishable items might be cooked and served as an impromptu prepared lunch for clients. Other impromptu serving of clients characterized exceptions.

Exceptions were circumstances where workers ignored established rules based on clients’ perceived needs and/or personal ethics. Workers consistently reported not wanting to turn people away because of--what they perceived to be--somewhat arbitrary rules. Nobody wanted people to go hungry and as a worker at one pantry (06W) noted, “a stomach’s a stomach.” Others felt that checking identification was discriminatory (09W), especially as many clients were undocumented. At least one pantry (20W) refused to accept local funding because of documentation requirements. Some workers made allowances for “special situations” (09W) or special populations (e.g., the elderly and disabled) so that they were spared waiting in line. Many workers cited a mission to help the most vulnerable, making the exception the rule when the actual rule ran counter to that mission.

DISCUSSION

The current study used qualitative and quantitative data to describe access to food pantries in two areas of the Bronx. Using Caspi and colleagues’ framework of five access dimensions (availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability),24 the findings of the current study demonstrate that access to pantry foods was limited overall. Food pantries were not reliably open and did not reliably have food. When they did have food, there was almost inevitably a mismatch between supply and demand. Pantry workers developed rules to address the mismatch and to try to create orderly and equitable systems for food provision. These rules were both a response to restricted supply and a cause of restricted access. There were exceptions to rules based on workers’ personal impressions, beliefs, and values, and workarounds to rules at times of food delivery. Both exceptions and workarounds added unpredictability to the consistency and regularity that rules would otherwise establish for access.

Access considerations in most prior of the literature on food pantries has been focused on single dimensions. Some studies examined accessibility (i.e. geographic location), showing for instance that food pantries play an especially important role in areas of high poverty and/or inadequate supermarket access.19 Other studies showed poor accessibility and accommodation in terms of pantry hours.56 A study conducted by Caspi and colleagues showed that census tracts with the highest proportions of racial/ethnic minorities and foreign-born groups also had the shortest distances to the nearest pantries.25 But another study showed lack of cultural accommodation and language barriers for Spanish-speaking clients, serving as impediments to equitable food provision.32 Research on availability demonstrates that the selection of food offerings from pantries is generally inadequate to support healthful diets,21,27,57–59 with mixed results in terms of dietary outcomes.24,25 Regarding acceptability, one study focusing on the perspective of pantry clients identified factors not identified in the current study; i.e., stigma and shame were barriers to access, and dignity was a facilitator.60

Another aspect of access relates to food demand relative to supply. In order to deal with the mismatch between demand and supply, pantries developed and used rules. Rules set by the pantries themselves included those pertaining to eligibility--e.g., related to age, or employment status, or last name (for example, last names beginning with A-M one session, last names beginning with N-Z for another). Rules had the effect of further restricting access; they reinforce findings of previous research documenting how ‘gatekeeping’ among pantry staff creates barriers to food provision.26,61,62

Not all rules restricting access came from pantries themselves though. Some rules came from suppliers--in some cases, for example, prescribing how food could be distributed.63 Pantry managers at some pantries refused to receive aid from such suppliers, hoping to avoid further restrictions on hungry people trying to obtain food.

Regardless of who sets the rules, the current study showed there was often rule breaking by pantry workers--in the form of workarounds and exceptions. Whether hungry individuals might receive food could depend a great deal on the timing of food deliveries and on the beliefs, values, and judgments of pantry workers. Most workers were volunteers from church communities that endorsed a mission to serve those in need over adherence to contrived rule sets.

Although the current study collected data from pantry workers, it is useful to consider access from the client perspective. From the client perspective, identifying pantries that offer food might reasonably be accomplished using a directory--e.g., a listing from a hunger-relief organization. For the current study, investigators used a listing from Food Bank For NYC39--the city’s largest hunger-relief organization and a food provider for most city pantries. It was presumed that this listing would be a complete and accurate source. However, study findings show that many listed pantries were not operating as posted.. Despite multiple attempts with repeat visits, investigators were unable to access half of all listed pantries visited. This experience is consistent with previous work to access New York City food pantries.56

The Food Bank For NYC listing was also missing food pantries that could have been open and operating. After study initiation, investigators came across a smaller listing of 40 pantry locations in the southern Bronx, that included 11 locations (eight in the southwest, three in the southeast) not listed by Food Bank For NYC.49 These missed pantries hosted sessions a listed 1–8 times per month, for 1–3 hours per session, with various eligibility and documentation requirements.49

Experienced pantry clients might have learned about such pantry sessions through means other than internet listings, and may have had a better sense of when food would actually be available. However, first-time users who seek information online might have had a similar experience to study investigators. As the listing for one pantry admonished, “call to confirm first,”49 highlighting the issues of unreliable hours and unpredictable food distribution.

The current study had notable strengths. Analyses included a sizeable proportion of the listed food pantries in two large urban areas. Data included qualitative and quantitative information, collected simultaneously and analyzed concurrently. Quantitative data included aspects of access within all five domains of an existing framework. Appreciating that the framework derived from local food sources in general, and that these food sources excluded food pantries,24 investigators conducted early pilot visits to identify unique aspects of pantry operations for subsequent data collection. Through pilot visits, investigators learned to ask about aspects of food access that would not pertain to other food sources (e.g., client-eligibility criteria, food distribution methods, and deviations from listed hours). Another strength of the study was that analyses distinguished between pantry locations and pantry sessions, a distinction absent from prior studies. This distinction is important because while most studies focus on physical locations and facilities, it is sessions that matter most in terms of access for clients. Access can differ by session, even at the same location.

Limitations of the current study included the non-random sampling. Although investigators endeavored to include as many listed pantries as possible in the study, complete inclusion was not possible, mostly due to pantries being closed when they were listed as being open. As a result of incomplete and non-random sampling, tests for statistical difference between geographic areas were not performed; they would not be meaningful. Moreover, almost all pantries were located in the southwest area, or right along the border with the southeast, making distinctions between pantries in the two areas somewhat artificial. Another limitation is that data collection was cross-sectional. However, investigators asked pantry workers about typical operations to get a sense of conditions over time, mitigating this limitation. Although data collection was conducted essentially from the perspective of clients seeking food, no data came from clients directly. Also none of the study investigators were themselves food-pantry clients. As such, the research did not access possible conversation currents among regular pantry users that could have provided greater certainty about pantry operations. For informed clients, there may have been better predictability in pantry hours than outsiders could appreciate. Indeed, prior work has suggested that pantry workers help clients in navigating a complex network of emergency food providers.64 Client perspectives of access would be a worthy focus of further study. A related limitation is that aspects of food pantry operations were categorized under single dimensions, when multiple dimensions might arguably apply--and be different for different clients. For example, hours of operation could be an issue of accessibility or of accommodation (or even of affordability if time needs to be taken off from work); produce selection might be considered in terms of availability, accommodation, or acceptability. Additionally, some access dimensions might be more fundamental than others. For example, physical proximity and convenient hours (accessibility) might matter less if offered items are not of satisfactory quality (acceptability) or culturally familiar (accommodation). Analyses did not attempt to rank factors related to access; this could be explored in future research. Finally, findings of the current study might not be generalizable to other locales and analyses did not consider root causes that might apply broadly to settings including in other cities. Several pantry workers noted funding deficiencies and government and supplier bureaucracies. Additionally a largely unskilled volunteer workforce may challenge the acquisition and provision of more plentiful and reliable offerings.

Conclusion

In a large sample of urban food pantries, the current study showed that access to food was limited. Based on the information published by a large hunger-relief organization and pantry provider, food pantries were not reliably open when--or in some cases even where--they were supposed to be. Pantries closed (temporarily or permanently) and changed their hours unpredictably, often without signage. When pantries were open, they did not reliably have food on hand to distribute. Adequate food was limited in terms of all five dimensions of access: availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability.

Although pantries developed rules to try to promote orderly and consistent provision of limited food supplies, rules had the effect of further restricting access for some. As such, rules were often inconsistent with the mission of workers who felt most compelled to feed the hungry. Rules could be broken at times of food deliveries, when there was immediate supply on hand for whomever might be present and hungry. Rules might also be broken in cases of extreme or compelling client need. Ultimately, adherence to rules was worker- and situation-dependent and, thus, unpredictable.

From a client perspective, it is possible that outward-appearing unpredictability might not be as marked as perceived by investigators. Experience in the pantry system may provide additional information to regular users. Still, for any individuals who are newly food-insecure, new to the pantry system, and referencing online sources, the incongruity with posted information is striking.

Future research should explore clients’ lived experiences with pantry access, including multiple access dimensions. Future research should also investigate fundamental drivers of mismatched supply and demand and ways to improve access to better serve those most in need of food.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Aimee Eden, PhD, for reviewing an early draft of this manuscript and providing helpful feedback.

Financial support

SCL is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award K23HD079606. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Student stipends through the Albert Einstein College of Medicine supported data collection. For data collection and management, the study used REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted through the Harold and Muriel Block Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore under grant UL1 TR001073.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Authorship

SCL conceived the study, designed the data collection tool and protocol, oversaw primary data collection, performed analyses, outlined the introduction and discussion sections, and drafted methods and results sections, including tables and figures. ZAG led the literature review, conducted primary data collection, contributed to qualitative data analysis, and assisted with the writing of introduction and discussion sections. HJF conducted primary data collection. AB contributed to qualitative data analysis. EBR contributed to qualitative data analysis and manuscript writing. CBS oversaw quantitative data analysis. ARM created the map and assisted with geographic considerations. KCS provided guidance on study planning, and contributed to the literature review, data analysis, and writing. All authors helped revise the manuscript.

Ethical Standards Disclosure

This study was considered exempt under federal regulations 45 CFR 46.101 (b) (2,4) and Einstein IRB policy

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. [Accessed June 11, 2018];Household Food Security in the United States in 2016 - A report summary from the Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. 2017 Sep; https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84973/err237_summary.pdf?v=42979.

- 2.Gundersen C, Dewey A, Crumbaugh A, Kato M, Engelhard E. Map the Meal Gap 2017: Highlights of Findings For Overall and Child Food Insecurity. [Accessed June 26, 2018];A Report on County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2015 by Feeding America. 2017 http://www.feedingamerica.org/research/map-the-meal-gap/2015/2015-mapthemealgap-exec-summary.pdf.

- 3.Carmichael SL, Yang W, Herring A, Abrams B, Shaw GM. Maternal food insecurity is associated with increased risk of certain birth defects. J Nutr. 2007 Sep;137(9):2087–2092. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010 Aug;164(8):754–762. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ke J, Ford-Jones EL. Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children’s health and behaviour. Paediatr Child Health. 2015 Mar;20(2):89–91. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kursmark M, Weitzman M. Recent findings concerning childhood food insecurity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009 May;12(3):310–316. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283298e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar P, Chung R, Frank DA. Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017 Feb-Mar;38(2):135–150. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gundersen C, Kreider B. Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2009 Sep;28(5):971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu JH, Bartfeld JS. Household food insecurity during childhood and subsequent health status: the early childhood longitudinal study--kindergarten cohort. Am J Public Health. 2012 Nov;102(11):e50–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosler AS, Michaels IH. Association Between Food Distress and Smoking Among Racially and Ethnically Diverse Adults, Schenectady, New York, 2013–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017 Aug 24;14(E71):E71. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010 Feb;140(2):304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seligman H, Bindman A, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya A, Kushel M. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaemsiri S, Olson EC, He K, Kerker BD. Food concern and its associations with obesity and diabetes among lower-income New Yorkers. Public health nutrition. 2012;15(1):39–47. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laraia BA, Borja JB, Bentley ME. Grandmothers, fathers, and depressive symptoms are associated with food insecurity among low-income first-time African-American mothers in North Carolina. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Jun;109(6):1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robaina KA, Martin KS. Food insecurity, poor diet quality, and obesity among food pantry participants in Hartford, CT. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013 Mar;45(2):159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempson K, Keenan DP, Sadani PS, Adler A. Maintaining food sufficiency: Coping strategies identified by limited-resource individuals versus nutrition educators. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003 Jul-Aug;35(4):179–188. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daponte BO, Lewis GH, Sanders S, Taylor L. Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 1998;30(1):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mabli J, Jones D, Kaufman P. Characterizing Food Access in America: Considering the Role of Emergency Food Pantries in Areas without Supermarkets. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2013 Jul 03;8(3):310–323. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin KS, Wu R, Wolff M, Colantonio AG, Grady J. A Novel Food Pantry Program: Food Security, Self-Sufficiency, and Diet-Quality Outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013 Nov 01;45(5):569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmet A, Depa J, Tinnemann P, Stroebele-Benschop N. The Dietary Quality of Food Pantry Users: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017 Apr;117(4):563–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food Bank of Central New York. [Accessed May 6, 2018];Food Bank vs. Food Pantry. 2018 https://www.foodbankcny.org/about-us/food-bank-vs-food-pantry/

- 23.Medicine NYAo. Food and Nutrition: Hard Truths About Eating Healthy. New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health & place. 2012 Sep;18(5):1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspi CE, Lopez AM, Nanney MS. Geographic Access to Food Shelves among Racial/ethnic Minorities and Foreign-born Residents in the Twin Cities, Minnesota. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2016 Jan 02;11(1):29–44. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2015.1066735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapnick M, Barnidge E, Sawicki M, Elliott M. Healthy Options in Food Pantries—A Qualitative Analysis of Factors Affecting the Provision of Healthy Food Items in St. Louis, Missouri. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akobundu UO, Cohen NL, Laus MJ, Schulte MJ, Soussloff MN. Vitamins A and C, calcium, fruit, and dairy products are limited in food pantries. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(5):811–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin KS, Colantonio AG, Picho K, Boyle KE. Self-efficacy is associated with increased food security in novel food pantry program. SSM population health. 2016 Mar 11;11(2):5. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin KS, Wu R, Wolff M, Colantonio AG, Grady J. A novel food pantry program: food security, self-sufficiency, and diet-quality outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Nov;45(5):569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson NLW, Just DR, Swigert J, Wansink B. Food pantry selection solutions: a randomized controlled trial in client-choice food pantries to nudge clients to targeted foods. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017 Jun 1;39(2):366–372. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remley DT, Kaiser ML, Osso T. A case study of promoting nutrition and long-term food security through choice pantry development. Journal of hunger & environmental nutrition. 2013;8(3):324–336. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Remley DT, Zubieta AC, Lambea MC, Quinonez HM, Taylor C. Spanish- and English-speaking client perceptions of choice food pantries. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2010;5(1):120–128. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunger Free America. One in Three Bronx Children Still Living in Food Insecure Households. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps: Building a Culture of Health, County by County. New York: Bronx; 2017. [Accessed February 26, 2018]. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/new-york/2017/rankings/bronx/county/outcomes/overall/snapshot. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austensen M, Been V, O’Regan KM, Rosoff S, Yager J. State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods, 2016 Focus: Poverty in New York City. NYU Furman Center. http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/SOC_2016_FOCUS_Poverty_in_NYC.pdf.

- 36.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed September 18, 2012];NYC UHF 34 Neighborhoods. http://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/EPHTPDF/uhf34.pdf.

- 37.Manson S, Schroeder J, Riper DV, Ruggles S. 2014 American Community Survey: 5-year data at the 5-digit ZIP Code Tabulation Area level. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2017. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 12.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NYC Health. [Accessed January 8, 2018];Community Health Survey, 2002–2016. https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/CHS/CHSXIndex.html.

- 39.Food Bank for New York City. [Accessed June 2, 2014];Find Food Pantries. http://www.foodbanknyc.org/CD6F9867-926E-0C0F-558E6A7EC4762F9E?city=Bronx&CatCode=PANTRY&go.x=25&go.y=23&go=go.

- 40.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon O, Frias R, Schechter CB. Urban farmers’ markets: accessibility, offerings, and produce variety, quality, and price compared to nearby stores. Appetite. 2015 Jul;90:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucan SC, Varona M, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Torrens L, Wylie-Rosett J. Assessing mobile food vendors (a.k.a. street food vendors)--methods, challenges, and lessons learned for future food-environment research. Public health. 2013 Aug;127(8):766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Varona M, Torrens L, Schechter CB. Mobile food vendors in urban neighborhoods-implications for diet and diet-related health by weather and season. Health & place. 2014 May;27:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucan SC, Maroko A, Shanker R, Jordan WB. Green Carts (mobile produce vendors) in the Bronx--optimally positioned to meet neighborhood fruit-and-vegetable needs? Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2011 Oct;88(5):977–981. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9593-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon DH, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Unexpected neighborhood sources of food and drink: implications for research and community health. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.011. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon D, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Sources of Foods That Are Ready-to-Consume (‘Grazing Environments’) Versus Requiring Additional Preparation (‘Grocery Environments’): Implications for Food-Environment Research and Community Health. J Community Health. 2018 Mar 14; doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-0498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee RE, Heinrich KM, Medina AV, et al. A picture of the healthful food environment in two diverse urban cities. Environmental health insights. 2010;4:49–60. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummins S, Smith DM, Taylor M, et al. Variations in fresh fruit and vegetable quality by store type, urban-rural setting and neighbourhood deprivation in Scotland. Public Health Nutr. 2009 Nov;12(11):2044–2050. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009004984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bogdewic SP. Participant observation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- 49.The New York City Coalition Against Hunger. [Accessed Dec 13, 2013];Neighbrohood Guide to Food and Assistance: Bronx Edition. 2013–2014. http://www.nyccah.org.

- 50.New York City Coalition Against Hunger. NYC Hunger Catastrophe avoided (For Now): Soaring Demand at Food Pantries and Soup Kitchens Counter-Balanced by Food Stamps Surge and Extra Recovery Bill Funding. 2009 http://www.nyccah.org/files/AnnualHungerSurveyReport_Nov09.pdf.

- 51.Mayer VL, Hillier A, Bachhuber MA, Long JA. Food insecurity, neighborhood food access, and food assistance in Philadelphia. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2014 Dec;91(6):1087–1097. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Handforth B, Hennink M, Schwartz MB. A qualitative study of nutrition-based initiatives at selected food banks in the feeding America network. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013 Mar;113(3):411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. The dance of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park Y, Quinn J, Florez K, Jacobson J, Neckerman K, Rundle A. Hispanic immigrant women’s perspective on healthy foods and the New York City retail food environment: A mixed-method study. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Jul;73(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gany F, Bari S, Crist M, Moran A, Rastogi N, Leng J. Food insecurity: limitations of emergency food resources for our patients. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2013 Jun;90(3):552–558. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoisington A, Manore MM, Raab C. Nutritional quality of emergency foods. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(4):573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nanney MS, Grannon KY, Cureton C, et al. Application of the Healthy Eating Index-2010 to the hunger relief system. Public Health Nutr. 2016 Nov;19(16):2906–2914. doi: 10.1017/S136898001600118X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grannon KY, Hoolihan C, Wang Q, Warren C, King RP, Nanney MS. Comparing the Application of the Healthy Eating Index–2005 and the Healthy Eating Index–2010 in the Food Shelf Setting. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017 Jan 02;12(1):112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greer AE, Cross-Denny B, McCabe M, Castrogivanni B. Giving Economically Disadvantaged, Minority Food Pantry Patrons’ a Voice: Implications for Equitable Access to Sufficient, Nutritious Food. Fam Community Health. 2016 Jul-Sep;39(3):199–206. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooksey-Stowers K, Read M, Wolff M, Martin K, Schwartz M. Food Pantry Staff Perceptions of Using a Nutrition Rating System to Guide Client Choice. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cahill CR, Webb Girard A, Giddens J. Attitudes and behaviors of food pantry directors and perceived needs and wants of food pantry clients. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 63.New York State Office of General Services. [Accessed April 22, 2018];The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) https://ogs.ny.gov/BU/SS/GDF/food-TEFAP.asp - 4.

- 64.Jones CL, Ksobiech K, Maclin K. “They Do a Wonderful Job of Surviving”: Supportive Communication Exchanges Between Volunteers and Users of a Choice Food Pantry. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017:1–21. [Google Scholar]