Abstract

Background

Symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and depression independently increase crash risk. Additionally, depression is both a risk factor for and a consequence of AD.

Objective

To examine whether a depression diagnosis, antidepressant use, and preclinical AD are associated with driving decline among cognitively normal older adults.

Methods

Cognitively normal participants, age ≥65, were enrolled. Cox proportional hazards models evaluated whether a depression diagnosis, depressive symptoms (Geriatric Depression Scale), antidepressant use, cerebrospinal fluid (amyloid-β42[A β42], tau, phosphorylated tau181 [ptau181]), and amyloid imaging biomarkers (Pittsburgh Compound B and Florbetapir) were associated with time to receiving a rating of marginal/fail on a road test. Age was adjusted for in all models.

Results

Data were available from 131 participants with age ranging from 65.4 to 88.2 years and mean follow up of 2.4 years (SD = 1.0). A depression diagnosis was associated with a faster time to receiving a marginal/fail rating on a road test and antidepressant use (p = 0.024, HR = 2.62). Depression diagnosis and CSF and amyloid PET imaging biomarkers were associated with driving performance on the road test (p≤0.05, HR = 2.51–3.15). In the CSF ptau181 model, depression diagnosis (p = 0.031, HR = 2.51) and antidepressant use (p = 0.037, HR = 2.50) were statistically significant predictors. There were no interaction effects between depression diagnosis, antidepressant use, and biomarker groups. Depressive symptomology was not a statistically significant predictor of driving performance.

Conclusions

While, as previously shown, preclinical AD alone predicts a faster time to receiving a marginal/fail rating, these results suggest that also having a diagnosis of depression accelerates the onset of driving problems in cognitively normal older adults.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, antidepressants, biomarkers, depression, driving, older adults

INTRODUCTION

By 2050, the United States will see a doubling of the population of older adults (age ≥ 65), a tripling of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases, and more older drivers (1 in 4) [1]. Currently, there are approximately 200,000 motor vehicle crashes annually, resulting in over 4,000 deaths among older drivers [2]. An increased crash risk among aging drivers has been attributed to a number of different factors, including older age, depression, medication side effects, and dementia [3–5].

The link between older age and increased crash risk and driving cessation has been attributed to disease, physical changes, sensory degeneration, and cognitive decline (independent of disease), which may interfere with daily functioning and operating a vehicle [6, 7]. Cognitive slowing due to depression is thought to be responsible for associations between depression and impaired driving performance and higher crash risk [8, 9]. Antidepressant use among patients with depression has been linked to better driving behavior compared to those with untreated depression [10]. Conversely, antidepressant use among persons without depression has an adverse effect on driving, including higher crash risk [11, 12]. A recent systematic review examined the risk of depression and antidepressants on motor vehicle crashes [13]. Across two decades and 19 studies conducted in seven countries, an increased crash risk was associated with depression (90% higher risk) and antidepressants use (40% higher risk) [13]. However, these studies were not age restricted to older adults and the combined effect of depression and antidepressants on driving were not analyzed.

In contrast to research on depression and driving, the literature on AD and driving has long established that individuals with symptomatic AD have a faster rate of decline in performance and increased risk of crashes [14–16]. More recent work has examined driving decline in preclinical AD, which is defined as the asymptomatic span of 15 to 20 years with biomarker evidence of the biological presence of AD pathology, but the individual remains cognitively normal. Studies have demonstrated that cognitively normal older adults with positive AD biomarkers make more errors driving, have a history of accidents and traffic violations, and are faster to receive a marginal/fail rating on a road test, compared to those with negative AD biomarkers [15, 17].

Depression has been also been identified as a risk factor of AD; older adults with both depression and AD experience faster changes in functional activities and overall decline in health [18, 19]. In community samples of older adults, depression prevalence ranges from 15 to 20%, but increases to 25% in adults with symptomatic AD [20, 21]. Additionally, antidepressant use tends to be higher in persons with AD [22]. A recent meta-analysis found that antidepressant use was associated with 1) a 65% increased risk of cognitive impairment in those age 65 or greater, 2) a three-fold risk for cognitive impairment for those under 65, and 3) a two-fold pooled risk of cognitive impairment/dementia [23]. Similar to symptomatic AD, depression is also found to be associated with preclinical AD [24, 25].

The extant literature demonstrates the negative impact of depression and antidepressant use on driving, but also the risk of depression and antidepressant use on AD. Directionality between these variables is not strongly established and continues to be examined in research. Given the projected growth of older adults (age ≥ 65), a subsequent increase in older motorists and increasing prevalence of symptomatic AD, it is timely to investigate their combined impact on driving performance in a single, longitudinal study. Since AD biomarkers (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] and imaging) can identify older adults who are at an increased risk of developing symptomatic AD, it is critical to understand the distinct roles of depression and antidepressant use in older adults with and without preclinical AD in the context of driving performance. We examined whether depression (remote or active), antidepressant use, and preclinical AD were associated with driving performance and driving decline among cognitively normal older adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved study protocols, consent documents, and questionnaires. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their informants. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture hosted at Washington University.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were required to be age 65 years or older, willing to take part in amyloid imaging and lumbar puncture for collection of CSF, and be cognitively normal as defined by a score of 0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [26]. Experienced clinicians integrate information from a neurological examination and interviews with the participant and a knowledgeable collateral source (family member or friend) to derive a CDR. At baseline, participants complete clinical and psychometric assessments, and biomarker testing (amyloid imaging and CSF) at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). At annual follow-up, participants complete the same clinical and psychometric assessments.

CSF

Amyloid-β42 (Aβ42), tau, and phosphorylated tau181 (ptau181) levels were measured using enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (INNOTEST; Fujirebio [formerly Innogenetics], Ghent, Belgium). Following an overnight fast, experienced neurologists use a 22-gauge Sprotte spinal needle to collect 20–30 mL of CSF via standard lumbar puncture into a polypropylene tube at 8 : 00 AM. After brief centrifugation, CSF samples were aliquoted and stored at –80◦C. All biomarker assays include a common reference standard, within-plate sample randomization and strict standardized protocol adherence. Samples were further examined if outlier values different from the common pool were obtained or if coefficients of variability exceeded 25%. Values of Aβ42 to define amyloid status (positive vs. negative) were determined using assay- and date-specific cutoffs that accounted for upward drift in INNOTEST immunoassay Aβ42 values over the years, as a result, there is not a single cutoff for Aβ42 [27]. Previous cutoffs that best distinguished individuals with very mild dementia (CDR 0.5) from those who are cognitively normal (CDR 0) were used for tau (339 pg/mL) and ptau181 (67 pg/mL) [28]. Lower levels of Aβ42 is a marker of amyloid plaques, while higher levels of tau and ptau181 reflect tau-related neuronal injury.

Amyloid imaging

Participants completed positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to determine amyloid burden using either Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) or florbetapir (F-AV-45) radiotracers in a Biograph mMR 124 scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A three-dimensional regions-of-interest yielded regional time-activity curves for different regions. The mean cortical binding potential (MCBP) was constructed by taking the mean of the BPs from brain regions (prefrontal cortex, gyrus rectus, lateral temporal cortex, and precuneus), which are established as having a higher degree of uptake in persons with symptomatic AD. Data were converted to standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) using the cerebellar cortex as a reference. Established SUVR cutoffs were used for florbetapir (≥1.219) and PiB (≥1.31) to indicate amyloid PET positivity [29, 30].

Depression and antidepressants

A depression diagnosis or a lifetime history of depression was operationally defined as participant indication that they had received a diagnosis of either active or remote depression. Self-report of receiving a physician’s diagnosis of depression was obtained from annual clinical assessments as recorded on the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set. The Geriatric Depression Scale short form (GDS) [31] is a 15-item screen for depression in older adults. Respondents answer “yes” or “no” for each item, with higher scores (range: 0–15) indicating greater depressive symptoms. Antidepressant use was derived from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set [32], Form A4 subject medications. A list of 30 actively prescribed and discontinued antidepressants was created and included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressant, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and mixed 5-HT (e.g., noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant, serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor) medications. This list was cross-referenced to Form A4 to determine which antidepressants were captured. Based on the list of medications, the antidepressants that were present included bupropion, citalopram, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, paroxetine, sertraline, trazodone, and venlafaxine. Antidepressant use was noted if the participant endorsed using any one of these 10 antidepressants at baseline assessment.

Road test

Annually, each participant completed the Washington University Road Test (WURT), a standardized road test [14] on a 12-mile course starting from a closed parking lot and progressing into traffic with complex intersections and unprotected left hand turns. The WURT has been used extensively over the past two decades to evaluate driving performance in stroke, healthy aging, and dementia populations. An examiner in the front seat provided direction and evaluated the driving performance. A rating of pass (no problems/errors), marginal (some safety concerns and errors), or fail (high risk and errors) is given at the end of the test. The examiner (a contracted driving instructor) was blinded to all information concerning the participant’s AD biomarkers, depression diagnosis, and antidepressant use. When a participant receives a fail rating, a geriatrician on our team provides feedback and if the participant consents, the information along with any new medical condition identified by the research team (e.g., field cut or poor hearing) is sent to their primary care physician to follow up for medical issues, which may explain the poor driving performance.

Statistical analyses

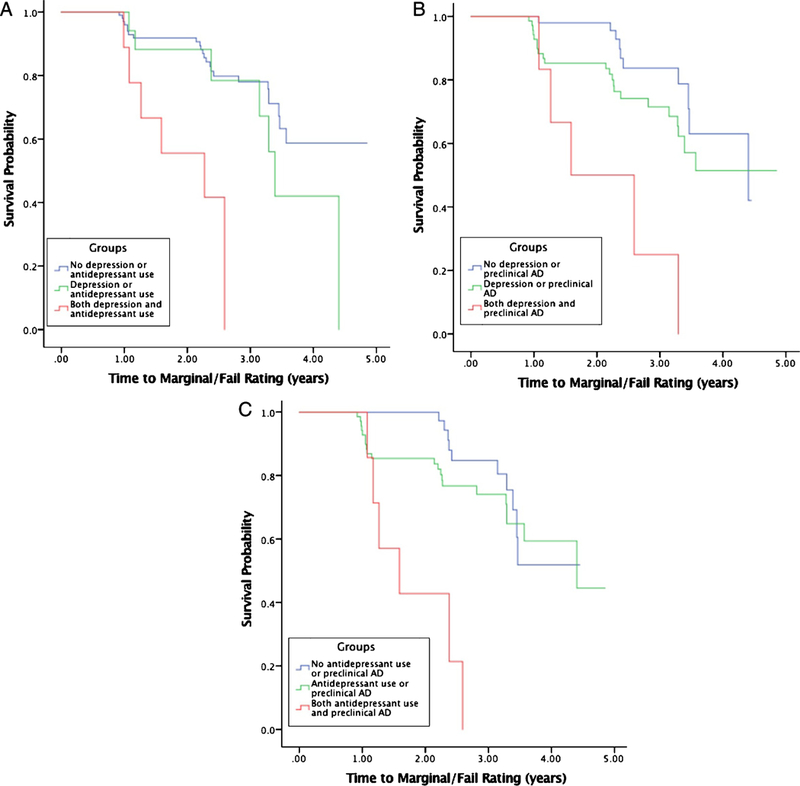

Descriptive statistics examined demographic variables and distribution of predictors. Data from participants who died or did not return for follow-up were censored at the date of last assessment. AD biomarkers were classified into four variables: CSF Aβ42, tau, ptau181, and amyloid imaging. Each variable was dichotomized into positive and negative based on established cut-offs referenced above. Similar to depression diagnosis (remote or active) and antidepressant use, GDS was dichotomized into 0 (no problems) and 1 (any problems) if participants endorsed any item. Each participant was required to have at least a baseline and follow-up road test evaluation but could have more than one follow-up. Driving decline on the road test was determined as the time from baseline assessment with a pass rating until receiving a rating of marginal/fail on follow up road test assessments. Kaplan-Meier depression diagnosis, antidepressant, and biomarker groups were also tested in predicting driving decline. The group associations between depression diagnosis, antidepressant use, and biomarkers on driving decline were examined graphically via Kaplan-Meier curves. For ease of interpretation, the 2×2 groups were reorganized in a trichotomous variable. For example, graphs examining the relationship between depression and antidepressant use on driving would have the corresponding groups: 1) no depression diagnosis and no antidepressant use 2) either depression diagnosis or antidepressant use, 3) yes depression diagnosis and yes antidepressant use.

RESULTS

Data from 131 participants were available for longitudinal analysis. At baseline, participants’ ages ranged from 65.4 to 88.2 years along with follow up times that ranged from 0.2 to 4.9 years (Table 1). Additionally at baseline, 16 (12.2%) participants had a depression diagnosis (remote or active), 21 (16.0%) indicated antidepressant use and 65 (50%) endorsed depressive symptoms (≥ 1 on GDS, the range was 0 to 6). Of those taking antidepressants, 12 (9.2%) participants did not have a depression diagnosis. In unadjusted analyses (Kaplan-Meier), depression (χ2(1) = 10.39, p = 0.001) and antidepressant use (χ2(1) = 7.28, p = 0.006) were associated with driving decline. While adjusting for age, both depression diagnosis and antidepressant use were again independently associated with driving decline (Table 2). However, only depression diagnosis was associated with driving decline when both depression, and antidepressant use were included in the same Cox proportional hazards model (Table 2). Depressive symptomatology as measured by the GDS was not significant in the unadjusted analyses (χ2(1) = 2.04, p = 0.153), when adjusting for age alone (Wald = 1.83, HR = 1.59, 95% CI [0.813,3.09] p = 0.176) or when adjusted for both age and antidepressant use (Wald = 0.912, HR = 1.39, 95% CI [0.703, 2.78] p = 0.340).

Table 1.

Demographics (N = 131)*

| Age, y | 72.1 ± 4.6 |

| Education, y | 16.3 ± 2.5 |

| Women, N | 71 (54.2%) |

| Race, Caucasian, N | 117 (89.3%) |

| APOE4+, N | 36 (27.5%) |

| MMSE, N | 29.3 ± 1.0 |

| Biomarkers | |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 910.1 ± 341.8 |

| CSF tau, pg/mL | 343.8 ± 194.4 |

| CSF ptau181, pg/mL | 62.2 ± 29.2 |

| Amyloid imaging | |

| Florbetapir, SUVR | 1.17 ± 0.54 |

| PiB, SUVR | 1.38 ± 0.60 |

| Depression, N | 16 (12.2%) |

| GDS, N | 0.87 ± 1.3 |

| Marginal/Fail rating, N | 37 (28.2%) |

| Driving follow up time, y | 2.50 ± 1.0 |

| Antidepressant use, N | 21 (16.0%) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 9 (6.9%) |

| Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 7 (5.3%) |

| Selective Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake | 7 (5.3%) |

| inhibitors | |

| Biomarker positivity | |

| Any | 69 (52.7%) |

| CSF Aβ42 | 37 (28.2%) |

| CSF tau | 50 (38.2%) |

| CSF ptau181 | 36 (27.5%) |

| Amyloid imaging | 30 (22.9%) |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; Aβ42, amyloid-β42; ptau181, phosphorylated tau181; SUVR, Standardized Uptake Value Ratios; PiB, Pittsburgh Compound B; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale

Mean ± Standard Deviation or count (percentage).

Table 2.

Predicting driving decline (Cox models controlling for age)*

| p | Wald | HR | 95% Cl Lower Upper | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model la | |||||

| Depression (only) | 0.003 | 8.66 | 3.20 | 1.48 | 6.95 |

| Antidepressant (only) | 0.023 | 5.15 | 2.43 | 1.13 | 5.25 |

| Model lb | |||||

| Depression | 0.024 | 5.12 | 2.62 | 1.14 | 6.03 |

| Antidepressant | 0.150 | 2.07 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 4.19 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Depression | 0.021 | 5.30 | 2.75 | 1.16 | 6.64 |

| Antidepressant | 0.185 | 1.76 | 1.81 | 0.75 | 4.34 |

| CSF Aβ42 | 0.042 | 4.14 | 2.01 | 1.03 | 3.94 |

| Depression | 0.012 | 6.36 | 2.91 | 1.27 | 6.69 |

| Antidepressant | 0.085 | 2.96 | 2.06 | 0.90 | 4.71 |

| CSF tau | 0.025 | 5.04 | 2.18 | 1.14 | 4.34 |

| Depression | 0.031 | 4.65 | 2.51 | 1.09 | 5.78 |

| Antidepressant | 0.037 | 4.36 | 2.50 | 1.06 | 5.92 |

| CSF ptau181 | 0.006 | 7.48 | 2.69 | 1.32 | 5.48 |

| Depression | 0.017 | 5.67 | 3.15 | 1.23 | 8.10 |

| Antidepressant | 0.132 | 2.26 | 1.98 | 0.81 | 4.83 |

| Amyloid imaging | 0.032 | 4.58 | 2.25 | 1.07 | 4.73 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Aβ42, amyloid-β42; ptau181, phosphorylated tau181

Degrees of freedom for all models = 1.

In the Cox proportional hazards model including the biomarker variables, depression diagnosis was a significant predictor in all four models, while antidepressant use was significant in the ptau181 model (Table 2). Additionally, CSF Aβ42, tau, ptau181, and amyloid imaging were also significant predictors in time to receiving a marginal/fail rating. Three and two-way factor interactions were not statistically significant. Like the first set of models, depressive symptoms as measured by the GDS were not significant in any model (statistics not reported). Participants who had both a depression diagnosis and used antidepressants were faster to receive a marginal/fail rating (χ2(2) = 17.35, p < 0.001) compared to those without a depression diagnosis and antidepressant use or those who were either depressed or used antidepressants (Fig. 1A). Participants who were positive for any biomarker (Aβ42, tau, ptau181, amyloid imaging) and used antidepressants were faster to receive a marginal/fail rating (χ2(2) = 14.41, p < 0.001) compared to those who were not using antidepressants and biomarker negative, or those who were either using antidepressants or biomarker positive (Fig. 1B). Similarly, participants with both a depression diagnosis and preclinical AD (indicated by positivity for CSF Aβ42, tau, ptau181, or amyloid PET) were significantly (χ2(2) = 13.90, p < 0.001) faster to receive a marginal/fail rating compared to other groups (Fig. 1C). Adjusted analyses confirmed the Kaplan-Meier results.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves examining relationships between depression, antidepressant use and preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD) as reflected by positivity on any of the four biomarkers: (A) depression and antidepressant use; (B) antidepressant use and preclinical AD; (C) depression and preclinical AD.

DISCUSSION

In our cognitively normal sample of older adults with and without preclinical AD, both a depression diagnosis (remote or active) and antidepressant use were independently associated with driving decline on a road test. When adjusting for age, depression diagnosis remained a significant predictor, but not antidepressant use. Depression diagnosis and antidepressant use together were also associated with driving decline when considered together with CSF ptau181 levels. AD has long been linked to faster decline in driving performance, greater crash risk, and driving cessation [16, 33, 34]. While depression diagnosis or symptoms and antidepressant use are prevalent among older adults, our study adds to existing knowledge indicating that both depression diagnosis and antidepressant use negatively influence driving and increase crash risk [23]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the associations between depression, antidepressant use, and preclinical AD on driving decline in a cognitively normal sample of older adults.

In the adjusted analyses, CSF ptau181, depression diagnosis, and antidepressants were all significant predictors of driving decline, while in the model tau, antidepressant use was approaching statistical significance. Similar to our prior work using the same cohort, depression symptoms was associated with tau pathology [24], but these results also showed associations with amyloid pathology as evidenced by results from both CSF and PET imaging. The lack of significance found between antidepressant use, CSF Aβ42 and tau, and PET imaging may be attributed to sample size given the direction of the findings. Additionally, our results are consistent with the literature showing the additive effect of both depression and antidepressant use on driving decline [13]. Links between depression and driving problems are most often explained as a result of greater cognitive load resulting in slowed or impaired processes due to AD [35]. Yet, these results demonstrate that driving decline associated with preclinical AD is also negatively impacted by depression with some influence of antidepressant use.

In our sample, approximately 12 of the 21 participants taking an antidepressant did not have a diagnosis of depression. While antidepressants are used to treat depression, they are also commonly used to treat chronic pain, anxiety, sleep problems, headaches, and smoking cessation [36]. As a result, older adults may be at risk for polypharmacy due to multiple, chronic conditions which results in poorer and adverse outcomes like falls [37, 38]. In depression treatment, fluoxetine is known to reduce the metabolism of other drugs like benzodiazepines, which may temporarily boost the concentration of other medications, thereby increasing adverse side-effects, which can impact critical abilities like reaction time, vision or vestibular stability [23].

In the driving literature, depressive symptomology is largely associated with driving cessation as older adults transition to being a non-driver [39]. In our study, depressive symptoms as evaluated by the GDS was not a significant predictor in any of the models predicting time to receiving a marginal/fail rating. This finding is important since it highlights the impact of a depression diagnosis, compared to self-report of current depressive symptoms, on driving decline. Additionally, given the floor effect with a majority of responses endorsing 0 or 1 on the GDS, these results for the lack of statistical significance make sense since self-report of depressive symptoms in this sample was very low. Prior work has shown that while depression symptoms were not associated with driving decline, there is a relationship with preclinical AD [40, 41].

Given the projected increase of AD prevalence to almost 14 million by 2050, in the US alone, one can also expect the prevalence of depression and antidepressant use to increase. Researchers using AD biomarkers are able to map out the course of preclinical AD, associated physical and cognitive decline, in addition to evaluating how these changes impact everyday functioning. Biomarkers are able to assess and determine the pathophysiological burden of AD and identify older adults at higher risk of decline. Current research is also finding that changes in emotive and mood domains occur in the preclinical stage of AD. Mood disorders like depression, while salient in older adults, tend to be eclipsed by complaints in memory and thinking, in addition to other diseases, which may impact physical functioning. The results of this study may have important implications for the aging population in terms of research and practice. AD biomarkers may be helpful to differentiate depression versus depressive symptoms to establish prevalence rates, but also assess the natural course of depression in the aging population and preclinical AD samples. In a similar vein, it may be helpful to continue early screens of older adults for depression or depressive symptoms, identify the effect of medications on functional tasks, and if needed, recommend a driving evaluation by a Driver Rehabilitation Specialist or occupational therapist. The asymptomatic, preclinical stage of AD may be the optimal intersection to screen and address deficits early on before they cascade and result in critical outcomes like a crash or mortality.

There are some limitations to our study. We were unable to formally operationalized depression via a structured criterion like the DSM. Rather data on depression was gather from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set, where a participant self-reported the condition based on their medical history. Given the stigma associated with mental illnesses and social desirability bias, it is highly likely that depression may have been underreported. Conversely, while rare, a person may also have reported having a depression diagnosis despite not having one. Data on depression age of onset, number of depressive episodes, and other indices of severity of a depression diagnosis were unavailable. Since participants were relatively healthy older adults from the community, the variability of responses in the GDS was very small (0–6), and as a result, we choose to dichotomize the variable into no versus any symptoms. The antidepressants captured on Form A4 about subject medication excluded other antidepressants like tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors; participants taking those antidepressants would have been incorrectly classified as not on antidepressants. Despite a modest sample size, the low number of participants with a depression diagnosis, depressive symptoms or using antidepressants may have impacted the results. This may also explain why the models testing two and three-way interactions were not statistically significant. Processed amyloid imaging data was missing for 11 participants in these analyses. Outside of antidepressants, we did not examine quantity or type of other medications participants may be taking, which may also impact their driving performance. Our participants were predominately Caucasian, well educated, did not have any other psychiatric or neurologic conditions/diagnosis, completed biomarker tests and annual driving assessments and may not be representative of the larger aging population. Given that those with depression are at risk for cognitive impairment and subsequent depression, we did not examine changes at subsequent follow up via neuropsychological testing. Finally, the road test (WURT) used to evaluate driving performance only evaluated the operational (control) and tactical (maneuvering) levels of driving, and not the strategic level (planning). It is expected that changes in preclinical AD would be first seen at the strategic level. Despite lacking a strategic level driving component, the road test was still able to elicit a signal in driving performance, indicating decline. However, limitations of the road test include use of an unfamiliar car, confound of anxiety (poor performance) or Hawthorne effect, different scoring systems, and stable weather conditions (e.g., sunny weather). Recent development of naturalistic driving methodologies using data loggers can be plugged into a participant’s vehicle via onboard diagnostic port and collect data in real time, in the actual environments that people drive daily [42]. Data may include distance travelled per trip, time and location, adverse driving behaviors like speeding or hard braking and impacts [43]. These results combined with conventional methods like the road test may be able to determine planning and navigation abilities, which may also start to become compromised in the preclinical phase.

In this study, our results suggest that even in cognitively normal older adults, driving, a vital and complex activity for daily living, is impacted by preclinical AD and depression. Older adults with both a remote or active depression diagnosis and preclinical AD were faster to receive a marginal/fail rating on standardized road test. Additionally, screening for depression and antidepressant use should be completed since older adults experience a number of important life changes (e.g., retirement, death of parents or friends, changes in residence, new diseases/diagnoses). Our results show that depression impacts driving decline and safety, particularly among older adults with preclinical AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01-AG056466, R01-AG043434, R03-AG055482, P50-AG05681, P01-AG03991, P01-AG026276]; AARFD-16–439140 Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). The authors thank the participants, investigators/staff of the Knight ADRC Clinical, Biomarker, Genetics and Neuroimaging Cores and the investigators/staff of the Driving Performance in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease study (R01-AG056466).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-0564r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].National Center for Statistics and Analysis (2015) 2015 older population fact sheet. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Traffic Safety Facts. ReportNo. DOT HS 812 372. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cunningham ML, Regan MA (2016) The impact of emotion, life stress and mental health issues on driving performance and safety. Road Transp Res 25, 40. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hunt LA, Murphy CF, Carr D, Duchek JM, Buckles V, Morris JC (1997) Reliability of the Washington University Road Test: A performance-based assessment for drivers with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 54, 707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sifrit KJ, Stutts J, Staplin L, Martell C (2010) Intersection Crashes among Drivers in their 60s, 70s and 80s. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet 54, 2057–2061. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME (1999) Older drivers and cataract: driving habits and crash risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54, M203–M211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bond EG, Durbin LL, Cisewski JA, Qian M, Guralnik JM, Kasper JD, Mielenz TJ (2017) Association between baseline frailty and driving status over time: a secondary analysis of The National Health and Aging Trends Study. Inj Epidemiol 4, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bulmash EL, Moller HJ, Kayumov L, Shen J, Wang X, Shapiro CM (2006) Psychomotor disturbance in depression: assessment using a driving simulator paradigm. J Affect Disord 93, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wickens CM, Smart RG, Mann RE (2014) The impact of depression on driver performance. Int J Ment Health Addict 12, 524–537. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ramaekers J (2017) Antidepressants and driving ability. Eur Psychiatry 41, S50–S51. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dassanayake T, Michie P, Carter G, Jones A (2011) Effects of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids on driving. Drug Saf 34, 125–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ravera S, van Rein N, De Gier JJ, de Jong-van den Berg L (2011) Road traffic accidents and psychotropic medication use in the Netherlands: a case–control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 72, 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hill LL, Lauzon VL, Winbrock EL, Li G, Chihuri S, Lee KC (2017) Depression, antidepressants and driving safety. Inj Epidemiol 4, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Carr DB, Barco PP, Wallendorf MJ, Snellgrove CA, Ott BR (2011) Predicting road test performance in drivers with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 59, 2112–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ott BR, Jones RN, Noto RB, Yoo DC, Snyder PJ, Bernier JN, Carr DB, Roe CM (2017) Brain amyloid in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is associated with increased driving risk. Alzheimers Dement 6, 136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ott BR, Heindel WC, Papandonatos GD, Festa EK, Davis JD, Daiello LA, Morris JC (2008) A longitudinal study of drivers with Alzheimer disease. Neurol 70, 1171–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head DM, Stout SH, Vernon EK, Ghoshal N, Garland B, Barco PP, Williams MM, Johnson A, Fierberg R, Fague MS, Xiong C, Mormino E, Grant EA, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ott BR, Carr DB, Morris JC (2017) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimers Dement 3, 74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF (2013) Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br JPsychiatry 202, 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Pot AM, Park M, Reynolds CF (2014) Managing depression in older age: psychological interventions. Maturitas 79, 160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reynolds K, Pietrzak RH, El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, Sareen J (2015) Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in US older adults: findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry 14, 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mussele S, Bekelaar K, Le Bastard N, Vermeiren Y, Saerens J, Somers N, Marie¨n P, Goeman J, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S (2013) Prevalence and associated behavioral symptoms of depression in mild cognitive impairment and dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28, 947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Puranen A, Taipale H, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Tolppanen AM, Tiihonen J, Hartikainen S (2017) Incidence of antidepressant use in community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease: 13-year follow-up. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 32, 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moraros J, Nwankwo C, Patten SB, Mousseau DD (2017) The association of antidepressant drug usage with cognitive impairment or dementia, including Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 34, 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Babulal GM, Ghoshal N, Head D, Vernon EK, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Roe CM (2016) Mood changes in cognitively normal older adults are linked to Alzheimer disease biomarker levels. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24, 1095–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM (2015) “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease A longitudinal analysis. Neurology 84, 617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurol 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schindler SE, Sutphen CL, Teunissen C, McCue LM, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Mulder SD, Scheltens P, Xiong C, Fagan AM (2018) Upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β 42 assay values for more than 10 years. Alzheimers Dement 14, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vos SJB, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, Cairns NJ, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM (2013) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12, 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, Bateman RJ, Cairns NJ, Aldea P, Cash L (2015) Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage 107, 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, Blazey TM, Christensen JJ, Vora S, Morris JC (2013) Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLoS. One 8, e73377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Montorio I, Izal M (1996) The Geriatric Depression Scale: a review of its development and utility. Int Psychogeriatr 8, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Ferris S, Foster NL, Galasko D, Graff-Radford N, Peskind ER (2006) The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stout SH, Babulal GM, Ma C, Carr DB, Head DM, Grant EA, Williams MM, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Roe CM (2017) Driving cessation over a 24 year period: Dementia severity and CSF biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement 14, 610–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Reinach SJ, Rizzo M, McGehee DV (1997) Driving with Alzheimer disease: the anatomy of a crash. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 11 Suppl 1, 21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Uc EY, Rizzo M, Anderson SW, Shi Q, Dawson JD (2004) Driver route-following and safety errors in early Alzheimer disease. Neurol 63, 832–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lampe L (2005) Antidepressants: not just for depression. Aust Prescr 28, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mallet L, Spinewine A, Huang A (2007) The challenge of managing drug interactions in elderly people. Lancet 370, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ziere G, Dieleman JP, Hofman A, Pols HA, Van Der Cammen TJM, Stricker BH (2006) Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. Br J Clin Pharmacol 61, 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ragland DR, Satariano WA, MacLeod KE (2005) Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60, 399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Babulal GM, Stout SH, Head D, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Roe CM (2017) Neuropsychiatric symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers predict driving decline: brief report. J Alzheimers Dis 58, 675–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Donovan NJ, Locascio JJ, Marshall GA, Gatchel J, Hanseeuw BJ, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Harvard Aging Brain Study (2018) Longitudinal association of amyloid beta and anxious-depressive symptoms in cognitively normal older adults. Am J Psychiatry 175, 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Babulal GM, Traub CM, Webb M, Stout SH, Addison A, Carr DB, Ott BR, Morris JC, Roe CM (2016) Creating a driving profile for older adults using GPS devices and naturalistic driving methodology. F1000Res 5, 2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Babulal GM, Stout SH, Benzinger TLS, Ott BR, Carr DB, Webb M, Traub CM, Addison A, Morris JC, Warren DK, Roe CM (2017) A naturalistic study of driving behavior in older adults and preclinical Alzheimer disease. J Appl Gerontol, 0733464817690679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]