Abstract

Background:

Understanding how women use PrEP is important for developing successful implementation programs. We hypothesized there are distinct patterns of adherence, related to HIV risk and other factors.

Setting & Methods:

We identified patterns of PrEP adherence and HIV risk behavior over the first 6 months of PrEP use, using data from 233 HIV-uninfected women in high-risk serodiscordant couples in a demonstration project in Kenya & Uganda. We modeled PrEP adherence, assessed by daily electronic monitoring, and HIV risk behavior using group-based trajectory models. We tested baseline covariates and risk behavior group as predictors of adherence patterns.

Results:

There were four distinct adherence patterns: high steady adherence (55% of population), moderate steady (29%), late declining (8%), and early declining (9%). No baseline characteristics significantly differed between adherence patterns. Adherence patterns differed in average weekly doses (6.7 vs 5.4 vs 4.1 vs 1.5, respectively). Two risk behavior groups were identified: steady HIV risk (78% of population) and declining (22%). Compared to women with declining HIV risk behavior, women with steady risk behavior were more likely to have high steady adherence (61% vs 35%) and less likely to have early (6% vs 17%) or late (4% vs 19%) declining adherence.

Conclusions:

Women’s use of PrEP was associated with concurrent HIV risk behavior; higher risk was associated with higher, sustained adherence.

Introduction

Women in many areas of the world remain at high-risk for HIV acquisition. In 2015, over 50% of new HIV infections in Sub-Saharan Africa occurred in women and 25% of all new infections occurred in women ages 15–24 [1]; these young women were twice as likely to acquire HIV compared to young men [1]. UNAIDS identified young women as a gap in HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa [2]. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been approved for HIV prevention as one way to address that gap [2]. Adherence among women was low in two randomized controlled trials (RCT) of PrEP [3,4]; several reasons emerged as to why women were not adhering during these placebo-controlled trials, including: lack of support from family and partners; fear of side effects; uncertainty of taking placebo; doubt that PrEP worked; low perceived HIV risk; difficulty taking a daily medication when not sick; and stigma of using an ARV [5,6]. However, two RCTs with high adherence did demonstrate efficacy among women [7–9]. In the context of known PrEP efficacy and international and national PrEP guidelines, open-label studies have demonstrated that women can use oral PrEP effectively [10,11]. Qualitative work from open-label studies identified barriers to PrEP use, including some, like side effects, stigma, and fear of disclosure, that were also identified in the RCTs [12,13]. However, social support, belief in PrEP efficacy, and perceived HIV risk were also seen as facilitators to PrEP use [12,13]. Unlike ART, PrEP is intended to be taken when persons are at risk of HIV exposure, a framework described as prevention-effective adherence [14]. Therefore, it will be key to understand when these risk periods occur and how well women adhere during risk periods to optimize PrEP delivery.

One way to better understand PrEP adherence is to characterize adherence patterns over time. Identifying women with certain adherence patterns can help counselors tailor their approaches for those in need of additional support, assist women to better assess their HIV risk, and connect women with peers. We hypothesized that women taking PrEP would display identifiable patterns of use, and these might be related to demographic factors as well as ongoing HIV risk behavior.

Methods

Study Population

Data were drawn from the Partners Demonstration Project, an open-label PrEP demonstration study among HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa, as previously described [10,15]. HIV serodiscordant couples were selected to be at high risk for HIV acquisition using a risk score we previously validated, which included age, cohabitation status, parity with study partner, unprotected sex, and viral load of the uninfected partner [16,17]; HIV-uninfected partners were encouraged to take PrEP until their partners had completed at least six months of antiretroviral treatment (“PrEP as a bridge to ART”). A total of 1,013 HIV serodiscordant couples, among which 334 couples had female HIV-uninfected partners, were enrolled at two sites each in Kenya and Uganda.

Participants were given electronic monitoring devices (MEMS caps, WestRock, Switzerland), which recorded daily bottle openings. MEMS data were downloaded and other variables collected at quarterly study visits, at which time PrEP (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 200mg/300 mg) was dispensed. PrEP was discontinued if a participant: acquired HIV; reported a severe, PrEP-related adverse event; began breastfeeding; had creatinine clearance <60mL/min; or at the study physician’s discretion. Midway through the study, the protocol was modified to allow women to continue PrEP during pregnancy if they chose. The study was approved by the University of Washington IRB and the ethic review committee for each site [10]. All participants provided written informed consent in their preferred language.

Statistical Analysis

For this analysis, women were excluded if they were HIV-infected at baseline (n=6), had <24 weeks of electronic monitoring data, including those with drug stops (n=94), or never initiated PrEP (n=1), leaving 233 HIV uninfected women with 24 weeks of complete data. Group-based trajectory modeling was used to identify patterns (or trajectories) of PrEP adherence and, separately, HIV risk behavior over the first 24 weeks of PrEP use. These models have been used to find adherence patterns in many health fields, including HIV [18,19]; detailed guides are available for these models as well [20,21] (Supplement). Using a specified number of trajectories and their shape (linear, quadratic, or cubic), the model estimates the proportion of the population belonging to each trajectory and calculates the posterior probability of an individual belonging to each trajectory based on their observed data; the individual is then assigned to the trajectory with the highest posterior probability [20,22–24].

Adherence was modeled on PrEP doses per week (range 0–7), using a censored normal (tobit) distribution [20], and HIV risk behavior was modeled on any sex (regardless of condom use or type of sexual partner) over the prior month, as reported at quarterly study visits, using a binomial distribution, over the first six months of PrEP use. For each outcome, models with 2–6 trajectories were compared using the Bayes test (recommended to be >10 to indicate good fit) and average posterior probabilities (recommended to be >0.7 to indicate good fit)[20,25]; when needed, content expertise was used to determine the most meaningful model. Once the number of trajectories was selected, the same criteria were used to compare linear, quadratic, and cubic terms for each trajectory. The distribution of covariates by assigned trajectory is presented.

Next, baseline covariates were added independently to the models; these are interpreted as the odds of being in each trajectory compared to a reference trajectory. Wald tests were computed to test for significance [22]. Covariates of interest as reported at enrollment were: perception of HIV risk from their study partner (dichotomized as high/moderate/unknown vs low/none); any report of problem drinking behaviors; marital status; parity; couple HIV risk score; and age (</≥25 years old). Likewise, time-varying covariates (also known as turning points) were added independently to the model; these are interpreted as the change in outcome when the covariate was present, within each trajectory [22]. Again, Wald tests were computed to test for significance. Pregnancy, partner’s use of ART, and frequency of sex over the prior month (with their study partner or outside partners) were recorded at follow-up study visits and included as possible covariates. Any significant covariates were included in the final model. We compared mean adherence across groups, using the assigned group as the predictor in a mixed effects model to account for repeated observations per woman.

Finally, we modeled the joint trajectories, using the final models for adherence and risk behavior. Joint trajectories allow the calculation of both the population and individual probabilities of belonging to each adherence trajectory, given a women’s risk behavior trajectory. We used chi-square tests to assess whether the population probability of each adherence trajectory differed by risk behavior trajectory. We also modeled the log10 individual probability of each adherence trajectory in separate linear regressions, with the individual’s probability of the steady risk behavior trajectory as the predictor (rather than assigned risk behavior trajectory, to account for possible error in trajectory assignment). As a sensitivity analysis, we included women missing adherence data (n=45); women who had a drug stop were still excluded as inability to use PrEP is a separate issue from adherence. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Of the 233 women initiating PrEP who were included in the present analysis, 22% were <25 years old at enrollment and 98% were married to the HIV-infected partner who participated in the Partners Demonstration Project (Table I). Recent sex with any partner was reported by 98% at enrollment and 51% felt they were at high/moderate HIV risk. During the six-months of follow-up, 7% of women became pregnant and 62% of their HIV-infected partners initiated ART. Overall, the average adherence to PrEP over this period was 82%, with an average 5.7 doses per week taken as measured by MEMS.

Table I.

Participant Characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics | % (N women) |

|---|---|

| N | 233 |

| <25 years old | 21.9% (51) |

| >8 years education | 33.5% (78) |

| HIV Risk Score, Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.4) |

| Married to Partner | 98.3% (229) |

| Parity with Partner, Median (IQR) | 1 (0,3) |

| Any sex, past month | 94.9% (221) |

| Any condomless sex, past month | 60.1% (140) |

| Problem drinking | 16.3% (38) |

| High/moderate/unknown perception of HIV risk | 50.6% (118) |

| During 24 week follow-up | |

| Weekly Doses, Mean (SD) | 5.7 (2.2) |

| Pregnant | 6.9% (16) |

| Partner Starts ART | 61.8% (144) |

| Any sex | 99.6% (232) |

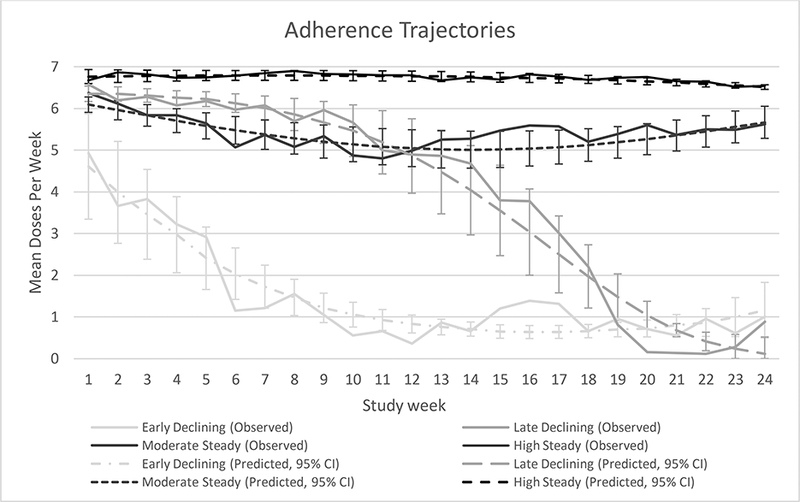

All the group-based trajectory models tested fit the adherence data well when using the Bayes test. A model with 4 groups was selected to be the most meaningful, with quadratic terms as the best fit; the average posterior probabilities were ≥0.97. We described the four adherence patterns as early declining adherence (estimated as 9% of the population), late declining adherence (8% of population), moderate steady adherence (29% of population), and high steady adherence (55% of population) (Figure 1). Adherence trajectories differed by average dose per week (p<0.0001) when modeled in a linear regression accounting for repeated observations, with the lowest average dose (1.5) in the early declining group and the highest average dose (6.7) in the high steady group (Table II). Differences in adherence were apparent in first week of PrEP use, when the early declining group had an average 5 doses, compared to 6.5, 6.4 and 6.7 in the late declining, moderate, and high steady groups respectively. Furthermore, when comparing average adherence over the first 12 weeks to the latter 12 weeks, there was no difference for the two steady adherence groups (6.8 to 6.7 and 5.4 to 5.4 average doses per week for the high and moderate steady adherence trajectories). However, there were notable differences for the two declining groups: 5.9 average doses per week over the first 12 weeks compared to 2.2 over the latter 12 weeks for the late declining groups; and 2.2 average doses per week then 0.7 for the early declining group.

Figure 1: Group-based Trajectories of Adherence.

Over the first six months of PrEP use, four adherence trajectories were identified. Dotted lines represent the predicted values from the models, with 95% confidence intervals; solid lines represent the observed data.

Table II.

Participant Characteristics by Adherence Trajectories

| Baseline Characteristics | Group 4 (High Steady) (n=130) |

Group 3 (Moderate Steady) (n=66) |

Group 2 (Late Decline) (n=17) |

Group 1 (Early Decline) (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 years old | 14.6% (19) | 25.8% (17) | 35.3% (6) | 45.0% (9) |

| >8 years education | 30% (39) | 34.9% (23) | 52.9% (9) | 35.0% (7) |

| HIV Risk Score, Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.8 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.0) | 6.7 (1.7) |

| Married to Partner | 99.2% (129) | 97.0% (64) | 94.1% (16) | 100.0% (20) |

| Parity with Partner, Median (IQR) | 1.5 (0, 3) | 1 (0,2) | 1 (1,3) | 1 (0,2) |

| Any sex, past month | 95.4% (124) | 93.9% (62) | 100.0% (17) | 90.0% (18) |

| Any condomless sex, past month | 61.5% (80) | 60.6% (40) | 52.9% (9) | 55.0% (11) |

| Problem drinking | 13.9% (18) | 24.2% (16) | 17.7% (3) | 5.0% (1) |

| High/moderate/unknown perception of HIV risk | 50% (65) | 54.5% (36) | 47.1% (8) | 45.0% (9) |

| Site | ||||

| Thika | 23.1% (30) | 16.7% (11) | 17.7% (3) | 20% (4) |

| Kampala | 33.1% (43) | 48.5% (32) | 47.1% (8) | 30% (6) |

| Kabwohe | 21.5% (28) | 12.1% (8) | 5.9% (1) | 15% (3) |

| Kisumu | 22.3% (29) | 22.7% (15) | 29.4% (5) | 35% (7) |

| During 24 week follow-up | ||||

| Weekly Doses, Mean (SD) | 6.7 (0.8) | 5.4 (2.0) | 4.1 (2.9) | 1.5 (2.2) |

| Pregnant | 5.4% (7) | 10.6% (7) | 11.8% (2) | 0.0% (0) |

| Partner Starts ART | 65.4% (85) | 59.1% (39) | 58.8% (10) | 50.0% (10) |

| Any sex | 99% (129) | 100% (66) | 100% (17) | 100% (20) |

Association between charactersitics and adherence trajectories: age (p=0.25); education (p=0.22); problem drinking (p=0.18); HIV risk perception (p=0.75); pregnancy (time-varying, p=0.57); partner’s ART use (time-varying, p<0.0001)

Age, education, alcohol use, HIV risk perception, and pregnancy (Table II) were not statistically associated with adherence trajectory by Wald Test when tested individually as time-independent (or time-dependent, for pregnancy) covariates: age, p=0.25; education, p=0.22; drinking, p=0.18; risk perception, p=0.75; pregnancy, p=0.57. Having their HIV-infected partner start ART was statistically significant (p<0.0001 by Wald test) and was included in the final model (Figure 1). Specifically, late decliners took 0.5 more doses on average during weeks when their partner was on ART, comparedwhen their partners were not on ART (p=0.008, Supplemental Figure 1). On the other hand, early decliners took 0.9 fewer doses on average during weeks when their partner was on ART (p<0.001) compared to when their partners were not on ART. For the moderate and high steady trajectories, the effect of having a partner on ART was not significant (−0.2 doses per week, p=0.15 and 0.02 doses per week, p=0.57, respectively).

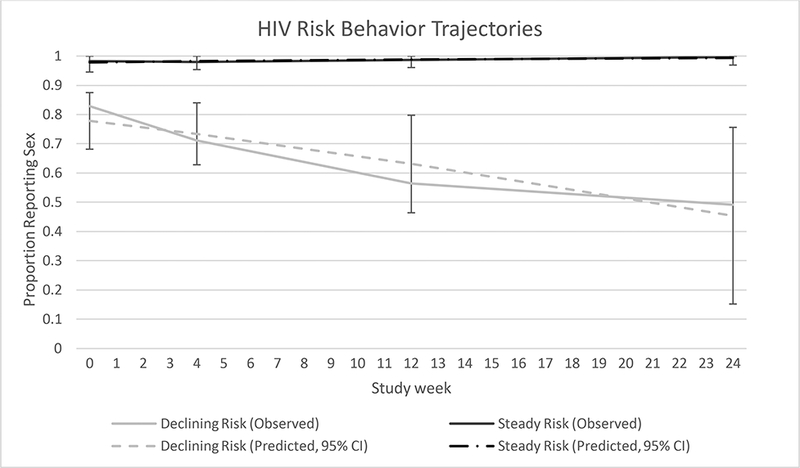

Next, we identified HIV risk behavior trajectories, based on any reported sex in the prior month. A model with two linear trajectories was the best fit (Figure 2); the average posterior probabilities were ≥0.86. The two risk behavior trajectories were defined as declining risk (an estimated 22% of the population) and steady risk (78% of population). There did not appear to be any differences by baseline or time-varying covariates (Table III); age was tested in the model a priori and was not significant, p=0.62. There was an average of 5.9 doses per week in the steady risk group compared to 5.1 in the declining risk group, which was statistically but likely not clinically significant (p=0.002).

Figure 2: Group-based Trajectories of Risk Behavior.

Over the first six months of PrEP use two risk behavior trajectories were identified based on reported sexual activity. Dotted lines represent the predicted values from the models; solid lines represent the observed data.

Table III.

Participant Characteristics by Risk Behavior Trajectories

| Baseline Characteristics | Group 2 (Steady Risk) (n=186) |

Group 1 (Declining Risk) (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| <25 years old | 22.0% (41) | 21.3% (10) |

| >8 years education | 32.3% (60) | 38.3% (18) |

| HIV Risk Score, Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.4) |

| Married to Partner | 98.4% (183) | 97.9% (46) |

| Parity with Partner, Median (IQR) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,2) |

| Any sex, past month | 97.3% (181) | 85.1% (40) |

| Any condomless sex, past month | 60.8% (113) | 57.5% (27) |

| Problem drinking | 17.2% (32) | 12.8% (6) |

| High/moderate/unknown perception of HIV risk | 50.0% (93) | 53.2% (25) |

| Site | ||

| Thika | 21.5% (40) | 17.0% (53) |

| Kampala | 38.2% (71) | 38.3% (18) |

| Kabwohe | 19.4% (36) | 8.5% (4) |

| Kisumu | 21.0% (39) | 36.2% (17) |

| During 24 week follow-up | ||

| Weekly Doses, Mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.6) |

| Pregnant | 7.5% (14) | 4.3% (2) |

| Partner Starts ART | 61.3% (114) | 63.8% (30) |

| Any sex | 100.0% (186) | 97.9% (46) |

Association between charactersitics and risk behavior trajectories: age (p=0.62).

Finally, we modeled adherence and risk behavior trajectories jointly, using the final models for each (Figure 3). There were significant differences in the distribution of adherence trajectories by risk behavior group by Chi-square test, p<0.0001. Women with steady HIV risk were more likely to have high steady adherence, compared to those declining risk. Conversely, women with declining HIV risk were more likely to have early or late declining adherence, compared to those with steady HIV risk. This pattern was the same when examining the individual adherence probabilities by steady HIV risk probability, with p<0.01 for all comparisons. Results from the sensitivity analysis (n=278) were consistent with those already described.

Figure 3: Population Probability of Adherence Trajectory by Risk Group.

The probability of being in the high steady, early declining, or late declining adherence trajectory differed according to risk trajectory, p<0.0001 (Chi-square test).

One woman in this analysis acquired HIV, 12 months after enrollment. During her first 6 months of use, she was characterized as early declining adherence and steady HIV risk behavior.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of data from East African women in HIV serodiscordant heterosexual partnerships who were taking PrEP for HIV prevention, we found evidence of different trajectories of adherence and of ongoing HIV risk behavior. Most women had high or moderate steady adherence, with average doses of 6.7 and 5.4 per week respectively over the first 6 months of PrEP use; likewise, most women remained at steady HIV risk over the first 6 months of PrEP use. However, we also identified two declining adherence trajectories. We did not find signficant differences in baseline characteristics that could differentiate between adherence trajectories. However, there were significant associations between sexual risk behavior and adherence trajectories. Specifically, women with a steady risk trajectory during follow-up were more likely to have a high steady adherence trajectory and less likely to have early or late declining adherence trajectories.

These results suggest that women align their PrEP use to times of HIV risk behavior, consistent with prevention-effective adherence [14,26]. Preventive-effective adherence is optimal both for the individual woman as well as for the health system, as it maximizes prevention while minimizing costs and side-effects when PrEP is not needed [14]. Prevention-effective adherence also distinguishes PrEP, which is only needed while at risk, from ART use, which is taken for life [14]. However, women may benefit from additional support in assessing their HIV risk; roughly 11% of women with steady risk had early or late declining adherence - including one woman who seroconverted to HIV - indicating a potential misalignment in adherence and risk. We found no associations between adherence and baseline risk perception, which underlies the difficulty of assessing risk perception especially with a single question [27–29].

These results are also in line with previous work that found initial adherence may be related to adherence over follow-up [4,30]. For instance, in this analysis the early declining adherence group had the lowest weekly dose from the first week of follow-up. However, not all women who start with high adherence will continue; the late declining adherence group for instance showed initially high adherence and was the least common trajectory.

Strengths of this study include use of daily electronic monitoring of adherence and the ability to compare adherence with HIV risk. MEMS caps are not without measurement error but have been shown to correspond with biomarkers of adherence better than self-report [10,31]. This analysis had a limited sample size, especially with infrequent assessments of risk behavior which led to few time points for the risk trajectory models; this may also have limited the power to detect associations with baseline characteristics. In addition, we cannot determine that HIV risk led to adherence; while the data support the idea of prevention-effective adherence, an alternative explanation is that women took more risks when adherence was high. However, previous work has not shown evidence of risk compensation in heterosexual couples using PrEP [32], and the degree of risk behavior seen on average during follow-up in this study was not greater than what was present at baseline. Finally, women in this study were members of known HIV-serodiscordant couples, whereby HIV risk may be easily identified; these results may not be generalizable to women in other situations, in which they do not clearly know their HIV risk.

In conclusion, we found evidence of distinct PrEP adherence patterns, which may be useful for implementing and understanding PrEP use in high-risk settings. Importantly, our results suggest that women may align their PrEP use with their HIV risk behavior, which would be the most efficient and cost-effective use of PrEP. Adherence counseling that improves women’s assessments of their HIV risk may be important for PrEP implementation. Tools to help women better assess their HIV risk and understand when to use PrEP may motivate and enable women to effectively adhere and protect themselves from HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the couples who participated in this study.

Funding: The Partners Demonstration Project was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (R01 MH095507), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1056051), and the US Agency for International Development (AID-OAA-A-12–00023). Additional funding for the present analysis came from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH098744). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, NIH, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: JMB has led studies with pre-exposure prophylaxis medication donated by Gilead Sciences and served on an advisory committee.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent: The University of Washington Human Subjects Division and ethics review committees at each site (the National HIV/AIDS Research Committee of the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology or the Ethics Review Committee of the Kenya Medical Research Institute) approved the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent in their preferred language in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Partners Demonstration Project Team

Coordinating Center (University of Washington) and collaborating investigators (Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital): Jared Baeten (protocol chair), Connie Celum (protocol co-chair), Renee Heffron (project director), Deborah Donnell (statistician), Ruanne Barnabas, Jessica Haberer, Harald Haugen, Craig Hendrix, Lara Kidoguchi, Mark Marzinke, Susan Morrison, Jennifer Morton, Norma Ware, Monique Wyatt

Project sites:

Kabwohe, Uganda (Kabwohe Clinical Research Centre): Stephen Asiimwe, Edna Tindimwebwa

Kampala, Uganda (Makerere University): Elly Katabira, Nulu Bulya

Kisumu, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute): Elizabeth Bukusi, Josephine Odoyo

Thika, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Washington): Nelly Rwamba Mugo, Kenneth Ngure

Data Management was provided by DF/Net Research, Inc. (Seattle, WA). PrEP medication was donated by Gilead Sciences.

References

- 1.AIDS by the Numbers [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2016. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/AIDS-by-the-numbers-2016_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention Gap Report [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2016. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-Based Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, Agot K, Ahmed KMbc, Taylor J, et al. Participants’ explanations for non adherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women’s Experiences with Oral and Vaginal Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: The VOICE-C Qualitative Study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2015 Aug 3];9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3931679/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, Campbell JD, Donnell D, Bukusi E, et al. Efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high risk heterosexuals: subgroup analyses from the Partners PrEP Study. AIDS Lond Engl [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2015 Apr 17];27. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3882910/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Heterosexual HIV Transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:423– 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Mugo NR, Katabira E, Bukusi EA, et al. Integrated Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to HIV-1-Serodiscordant Couples: A Prospective Implementation Study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekker L-G, Roux S, Sebastien E, Yola N, Amico KR, Hughes JP, et al. Daily and non-daily pre-exposure prophylaxis in African women (HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town Trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet HIV [Internet]. 2017; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235230181730156X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker L-G, Roux S, Atujuna M, Sebastian E, et al. Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT Study-Provided Open-Label PrEP Among Women in Cape Town: Facilitators and Barriers Within a Mutuality Framework. AIDS Behav. 2017;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel RC, Stanford-Moore G, Odoyo J, Pyra M, Wakhungu I, Anand K, et al. “Since both of us are using antiretrovirals, we have been supportive to each other”: facilitators and barriers of pre-exposure prophylaxis use in heterosexual HIV discordant couples in Kisumu, Kenya. JIAS. 2016;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, Curran K, Koechlin F, Amico KR, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015;29:1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haberer JE, Kidoguchi L, Heffron R, Mugo N, Bukusi E, Katabira E, et al. Alignment of adherence and risk for HIV acquisition in a demonstration project of pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda: a prospective analysis of prevention-effective adherence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, John-Stewart G, Celum C, Nakku-Joloba E, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1 serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irungu EM, Heffron R, Mugo N, Ngure K, Katabira E, Bulya N, et al. Use of a risk scoring tool to identify higher-risk HIV-1 serodiscordant couples for an antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention intervention. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2017 Nov 29]; 16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5067880/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass TR, Battegay M, Cavassini M, De Geest S, Furrer H, Vernazza PL, et al. Longitudinal analysis of patterns and predictors of changes in self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Shoptaw S, Landovitz RJ, Javanbakht M, et al. Sexual risk trajectories among MSM in the United States: implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:579–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagin DS. Group-based Modeling of Development Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones BL. traj: group-based modeling of longitudinal data [Internet]. Traj Group-Based Model. Longitud. Data. [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones/index.htm

- 22.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in Group-Based Trajectory Modeling and an SAS Procedure for Estimating Them. Sociol Methods Res. 2007;35:542–71. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental Trajectory Groups: Fact or a Useful Statistical Fiction?*. Criminology. 2005;43:873–904. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-Based Trajectory Modeling in Clinical Research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS Procedure Based on Mixture Models for Estimating Developmental Trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:374–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal J, Jain S, Dube M, Sun X, Ellorin E, Hoenigl M, et al. Recent HIV Risk Behavior and Partnership Type Predict PrEP Adherence in Men who have sex with Men [Internet] San Diego, CA; 2017. [cited 2017 Dec 8]. Available from: https://idsa.confex.com/idsa/2017/viewsessionpdf.cgi [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Development of the Perceived Risk of HIV Scale. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1075–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley H, Tsui A, Hindin M, Kidanu A, Gillespie D. Developing scales to measure perceived HIV risk and vulnerability among Ethiopian women testing for HIV. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1043–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll JJ, Heffron R, Mugo N, Ngure K, Ndase P, Asiimwe S, et al. Perceived Risk Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus Serodiscordant Couples in East Africa Taking Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43:471–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, Brantley J, Bangsberg DR, Haberer JE, et al. HIV Protective Efficacy and Correlates of Tenofovir Blood Concentrations in a Clinical Trial of PrEP for HIV Prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:340–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musinguzi N, Muganzi CD, Boum Y, Ronald A, Marzinke MA, Hendrix CW, et al. Comparison of subjective and objective adherence measures for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection among serodiscordant couples in East Africa. AIDS Lond Engl. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mugwanya KK, Donnell D, Celum C, Thomas KK, Ndase P, Mugo N, et al. Sexual Behavior of Heterosexual Men and Women Receiving Antiretroviral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention: A Longitudinal Analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1021–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.