Graphical abstract

Keywords: Fluoride, P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles, Aqueous solution, Isotherm, Kinetic

Abstract

High concentration of fluoride above the optimum level can lead to dental and skeletal fluorosis. The data presents a method for its removal from fluoride-containing water. P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles was applied as an adsorbent for the removal of fluoride ions from its aqueous solution. The structural properties of the P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles before and after fluoride adsorption using the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) technique were presented. The effects of pH (2–11), contact time (15–120 min), initial fluoride concentration (10–50 mg/L) and P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dosage (0.01–0.1 g/L) on the removal of F− on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles were presented with their optimum conditions. Adsorption kinetics and isotherm data were provided. The models followed by the kinetic and isotherm data were also revealed in terms of their correlation coefficients (R2).

Specifications Table

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protocol data

-

•

The presented data established that P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles can be applied for the removal of fluoride with great efficiency.

-

•

Data on the isotherm, kinetics, and effect of process variables were provided, which can be further explored for the design of a treatment plant for the treatment of fluoride-containing industrial effluents where a continuous removal is needed on a large scale.

-

•

FTIR data for P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles were also provided.

-

•

The dataset will also serve as a reference material to any researcher in this field.

Description of protocol

Data

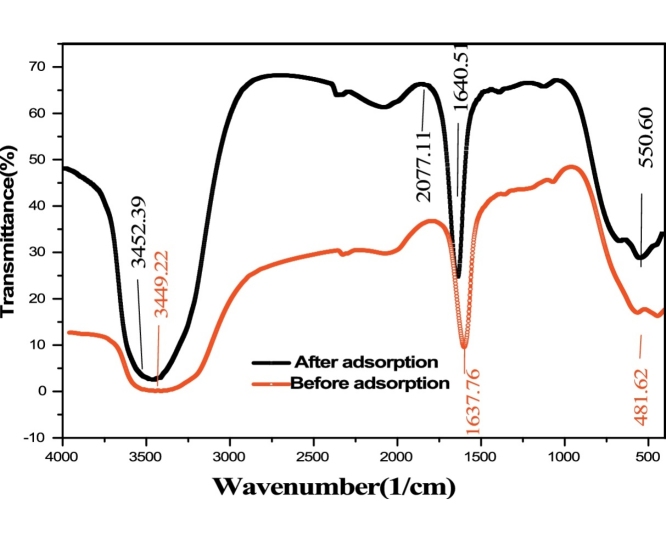

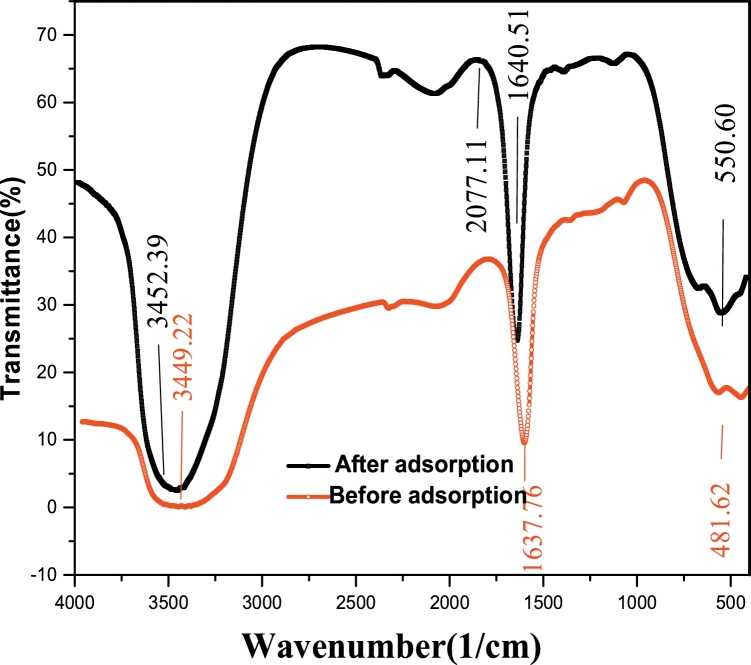

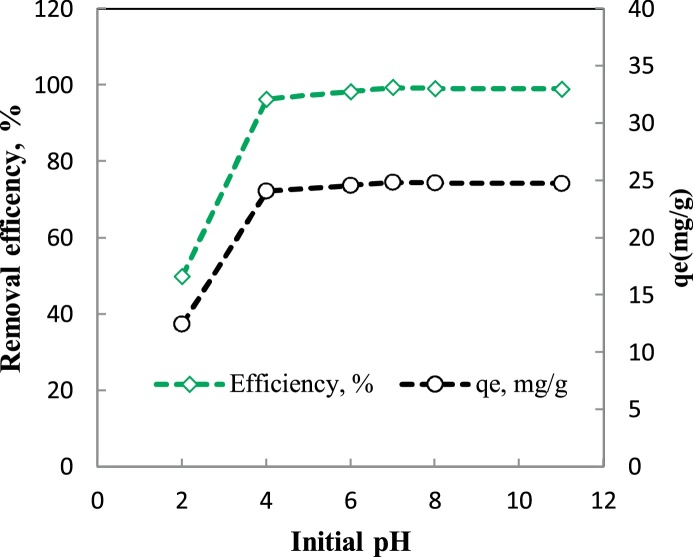

High concentration of fluoride is toxic and causes digestive disorders, fluorosis, endocrine, thyroid and liver damages, and also decreases the growth hormone [1,2]. In addition, it influences the metabolism of some elements such as calcium and potassium [3]. Fluoride must be properly reduced before its discharge to the water bodies. Adsorption can be considered as an effective method for the removal of fluoride [4,5]. The applicability of P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles for fluoride removal was reported. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) on the P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles is given in Fig. 1. Fig. 2 shows the schematic illustration for the synthesis of P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The functional groups present in the P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles before and after fluoride adsorption are given in Table 1. The estimated adsorption isotherm and kinetic parameters are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectra of the P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles before and after fluoride adsorption.

Fig. 2.

The schematic illustration of the synthesis of P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

Table 1.

Functional groups present in the P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles before and after fluoride adsorption.

| Peak (Absorbance) cm−1 |

Type of vibration or Bond source | Functional group name | Peak intensity description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adsorption | After adsorption | |||

| 481.62 | 550.60 | C—I stretch | Alkyl halides | Strong |

| 1637.16 | 1640.50 | N—H bend | 1° amines | Medium |

| 2025.20 | 2077.11 | —C C— stretch | Alkynes | Weak |

| 3449.22 | 3452.39 | O—H stretch, H— bonded | Alcohols and phenols | Strong and broad |

Table 2.

Isotherm and kinetic data for the sorption of fluoride on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

| Isotherms | Freundlich |

Langmuir |

Temkin |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Kf | 1/n | R2 | qm | KL | R2 | AT | B1 | |

| C0(mg/L) 25 |

0.9 | 79.4 | 0.013 | 0.9999 | 81.3 | 0.012 | 0.995 | 1.19 | 1.088 |

| Kinetics | Lagergren |

Ho |

Intraparticle diffusion |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | K1 | qe | R2 | K2 | qe | R2 | Kpi | c | |

| C0(mg/L) 25 |

0.6262 | 0.005 | 1.7 | 0.999 | 0.067 | 100 | 0.78 | 0.0041 | 97.9 |

Adsorption experiments

The adsorption experiment was conducted at batch mode using the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) method, that is, keeping a factor constant and varying the other factors to get the optimum condition of each variable. At first, for the purpose of this study, a stock solution of fluoride was prepared with distilled water from which other fluoride concentrations were prepared. The stock solution of fluoride (concentration of 1000 mg/L) was made by dissolving 2.21 g NaF in 1000 mL distilled water. A known mass of adsorbent (P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles) was added to 1 L of the water samples containing different concentrations of fluoride. The pH of the water sample was adjusted by adding 0.1 N HCl or NaOH solutions. The removal efficiency was determined by varying the different adsorption process parameters such as pH (2–11), contact time (15–120 min), initial fluoride concentration (10–50 mg/L) and P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dosage (0.01–0.1 g/L). To create optimal conditions, the solutions were agitated using orbital shaker at a predetermined rate (150 rpm). After each experimental run, the solution was filtered and the filtrate was analyzed for the residual fluoride concentration. The initial and residual fluoride concentrations in the solutions were analyzed by a UV–vis recording spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Model: CE-1021-UK) at a wavelength of absorbance (λmax): 570 nm [5].

Data analysis

The removal efficiency, R (%) and amount of fluoride adsorbed on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles, qe (mg/g) of the studied parameters were estimated based on the following formulas [[6], [7], [8]]:

| (1) |

Where C0 and Cf are the initial and residual fluoride concentrations (mg/g), respectively.

| (2) |

Where C0 and Ce are the initial and final equilibrium liquid phase concentration of fluoride (mg/g), respectively. M is the weight of the nano adsorbent (g) and V is the volume of the solution (L).

Influence of process variables

In this research, the influence of pH (2 - 11), contact time (15 - 120 min), initial fluoride concentration (15 - 50 mg/L) and P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dosage (0.01 - 0.1 g/L) on the removal efficiency was investigated.

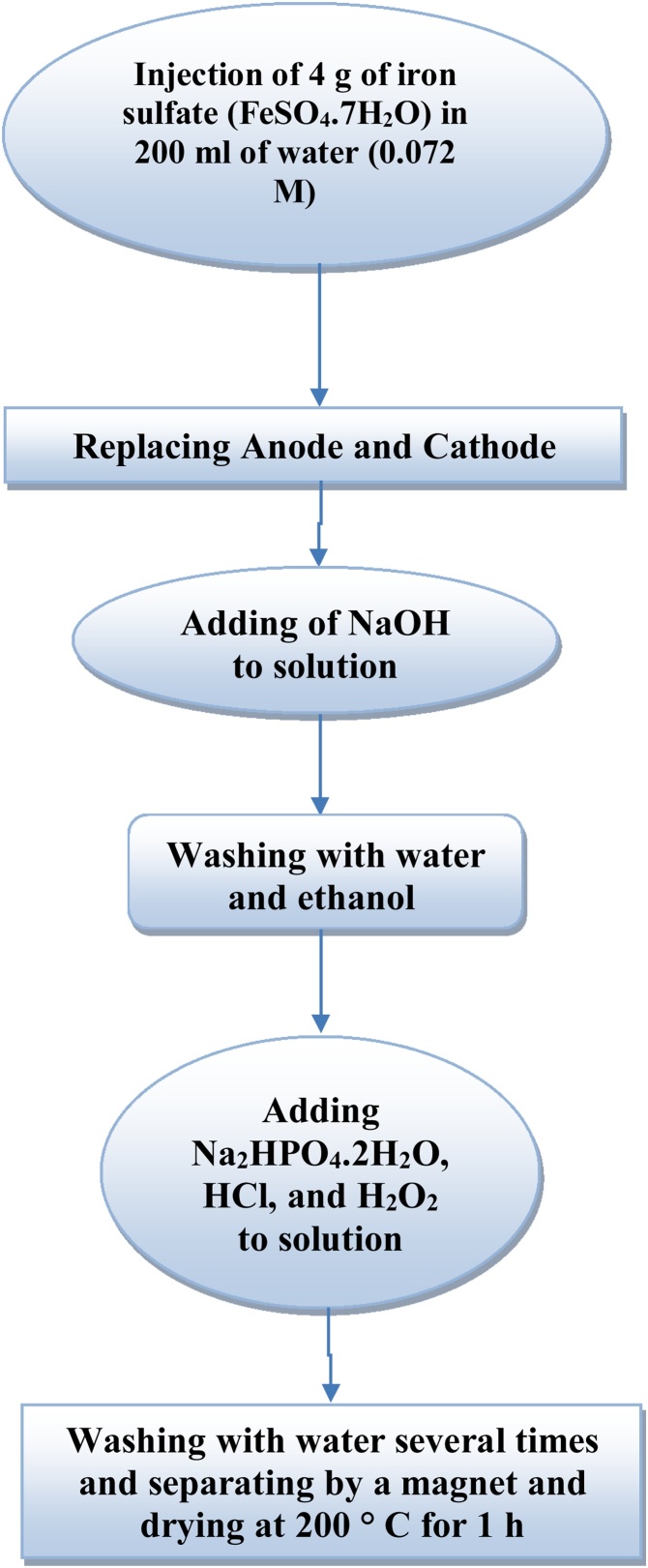

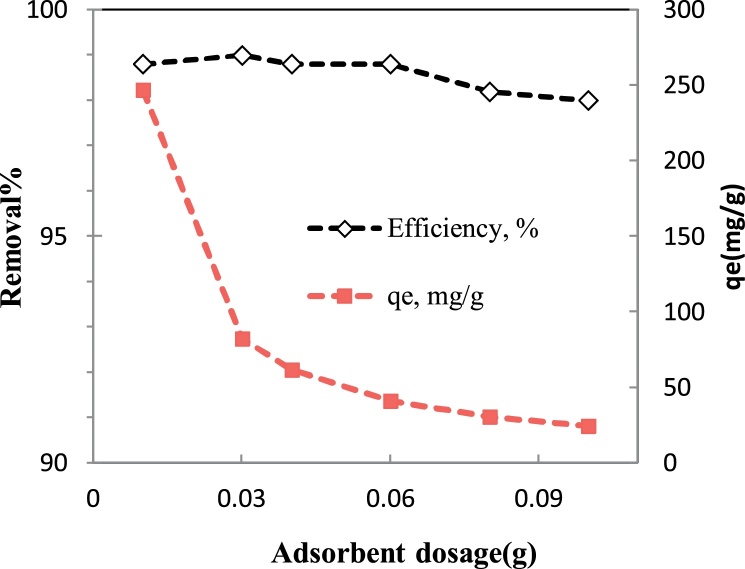

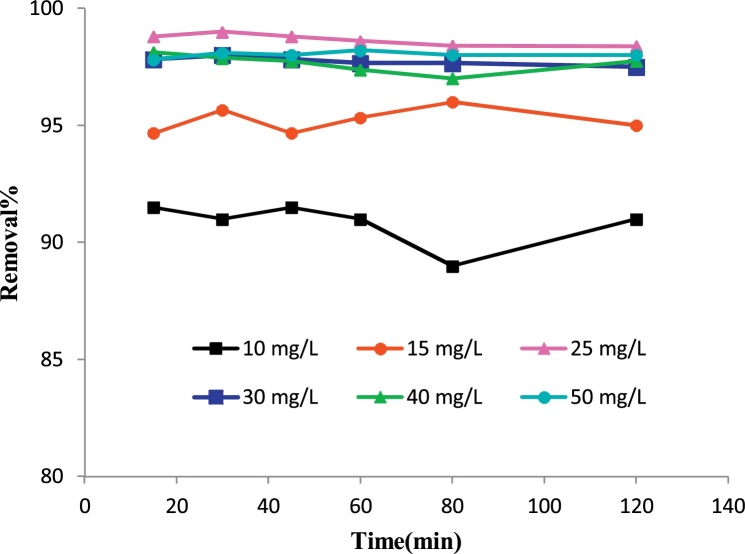

Higher removal efficiency was obtained at pH of 7 (Fig. 3), an adsorbent dosage of 0.02 g/L (Fig. 4), the initial fluoride concentration of 25 mg/L (Fig. 5) and contact time of 60 min (Fig. 5). This optimum conditions of pH 7, adsorbent dosage: 0.02 g/L, contact time: 30 min and initial fluoride concentration: 25 mg/L gave an efficiency of 99% (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH on the removal efficiency of fluoride on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

(Contact time: 30 min, dosage: 0.09 g/L, initial fluoride concentration: 10 mg/L).

Fig. 4.

Effect of adsorbent dosage on the removal efficiency of fluoride.

(Contact time: 30 min, optimum pH: 7, initial fluoride concentration: 10 mg/L).

Fig. 5.

Effect of initial fluoride concentration on the removal efficiency of fluoride (optimum P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dosage: 0.02g/L, optimum pH: 7).

Isotherm and kinetic modeling

An important physiochemical subject in terms of the evaluation of adsorption processes is the adsorption isotherm, which provides a relationship between the amount of fluoride adsorbed on the solid phase and the concentration of fluoride in the solution when both phases are in equilibrium [9]. To analyze the experimental data and describe the equilibrium status of the adsorption between solid and liquid phases, the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models were used to fit the adsorption isotherm data.

Several kinetic models have been applied to examine the controlling mechanisms of adsorption processes such as chemical reaction, diffusion control, and mass transfer [10]. Three kinetics models, namely pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion models were used in this study to investigate the adsorption of fluoride on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

Langmuir isotherm

For the Langmuir model, it is assumed that adsorbates attach to certain and similar sites on the adsorbent’s surface and the adsorption process occurs on the monolayer surface. The Langmuir equation can be rearranged to linear form for the convenience of plotting and determining the isotherm constants, KL and qm by drawing a curve of l/qe versus 1/Ce [11,12]:

| (3) |

Where qe (mg/g) is the amount of fluoride adsorbed per specific amount of adsorbent, Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the fluoride solution (mg/L), KL (L/mg) is Langmuir constant, and qm (mg/g) is the maximum amount of fluoride required to form a monolayer.

Freundlich isotherm

The Freundlich model is an empirical relationship between the parameters, qe, and Ce. It is obtained by assuming a heterogeneous surface with nonuniform distribution of the adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface, and can be expressed by the following equation [13,14]:

| (4) |

Where Kf and 1/n are the Freundlich constants related to adsorption capacity and adsorption intensity, respectively. The Freundlich constants can be obtained by plotting a graph of Log qe versus Log Ce based on the experimental data by applying the linear form of the Freundlich isotherm Eq. (4):

| (5) |

Temkin isotherm

In Temkin model, the surface adsorption theory was corrected considering possible reactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate. This model can be expressed as the following equation [15]:

| (6) |

Where AT and B1 are the Temkin constants. B1 is related to the heat of adsorption and AT is the equilibrium binding constant.

Lagergren kinetic model

Adsorption kinetic models are used to examine the rate of adsorption process and the potential rate controlling step. The Lagergren (pseudo-first-order) rate equation is expressed as Eq. (7) [16,17]:

| (7) |

Ho kinetic model

The Ho (pseudo-second-order) rate equation is given as [12,18]:

| (8) |

Where qe (mg g−1) and qt (mg g−1) are the amounts of fluoride adsorbed at equilibrium and at time t, respectively, K1 (min−1) is the pseudo-first-order rate constant of adsorption, and K2 (g mg−1 min−1) is the pseudo-second-order rate constant.

Intraparticle diffusion

For the intraparticle diffusion model (Eq. (9)), c is the intercept (mg/g) and Kpi is the slope. If intraparticle diffusion is involved in the adsorption process, then the plot of t0.5 versus qt would result in a linear relationship, and the intraparticle diffusion would be the controlling step if this line passed through the origin (C = 0). When the plots do not pass through the origin (C ≠ 0), this is indicative of some degree of boundary layer control and this further shows that the intraparticle diffusion is not the only rate controlling step, but also other processes may control the rate of adsorption [19,20].

| (9) |

Where qt (mg/g) is the amount of fluoride adsorbed at time t (min) and Kpi (mg/g min) is the intraparticle diffusion model rate constant.

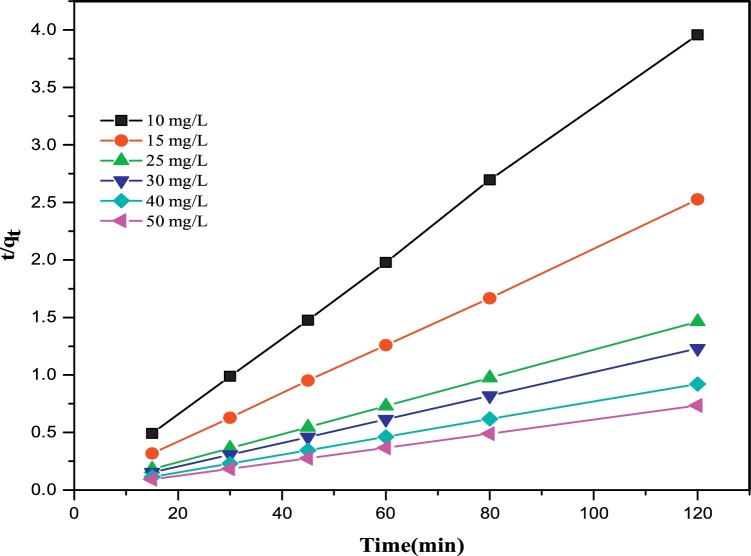

The estimated adsorption isotherm and kinetic parameter are presented in Table 2. Fig. 6 shows the adsorption kinetic (Ho) plot for fluoride removal on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The removal of fluoride on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles followed the Ho kinetic model with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.999 at 25 mg/L, suggesting that the rate-limiting step is a chemical adsorption process [21]. The isotherm data fitted into the Freundlich, Langmuir and Temkin isotherms but fitted more to the Langmuir isotherm, which indicates a monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface [14].

Fig. 6.

Pseudo-second-order (Ho) kinetic plot for fluoride removal on P/γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

Funding sources

This paper is the result of the approved project at Zabol University of Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Iran for their financial and spiritual support.

References

- 1.Rahmani A., Rahmani K., Dobaradaran S., Mahvi A.H., Mohamadjani R., Rahmani H. Child dental caries in relation to fluoride and some inorganic constituents in drinking water in Arsanjan, Iran. Fluoride. 2010;43:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobaradaran S., Fazelinia F., Mahvi A.H., Hosseini V. Particulate airborne fluoride from an aluminum production plant in Arak, Iran. Fluoride. 2009;42:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehghani M.H., Faraji M., Mohammadi A., Kamani H. Optimization of fluoride adsorption onto natural and modified pumice using response surface methodology: isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017;34:454–462. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravanipour M., Kafaei R., Keshtkar M., Tajalli S., Mirzaei N., Ramavandi B. Fluoride ion adsorption onto palm stone: optimization through response surface methodology, isotherm, and adsorbent characteristics data. Data Brief. 2017;12:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahramanlioglu M., Kizilcikli I., Bicer I. Adsorption of fluoride from aqueous solution by acid treated spent bleaching earth. J. Fluorine Chem. 2002;115:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi S., Kord Mostafapour F. Treatment of textile wastewater using a combined coagulation and DAF processes, Iran, 2016. Arch. Hyg. Sci. 2017;6:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmadi S., Mostafapour F.K. Survey of efficiency of dissolved air flotation in removal penicillin G from aqueous solutions. Br. J. Pharm. Res. 2017;15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmadi S., Banach A., Mostafapour F.K., Balarak D. Study survey of cupric oxide nanoparticles in removal efficiency of ciprofloxacin antibiotic from aqueous solution: adsorption isotherm study. Desal. Water Treat. 2017;89:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoshnamvand N., Bazrafshan E., Kamarei B. Fluoride removal from aqueous solutions by NaOH-modified Eucalyptus leaves. J. Environ. Health Sustain. Dev. 2018;3:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karthikeyan S., Sivakumar B., Sivakumar N. Film and pore diffusion modeling for adsorption of reactive red 2 from aqueous solution on to activated carbon prepared from bio-diesel industrial waste. E-J. Chem. 2010;7:S175–S184. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadi S., Igwegbe C.A. Adsorptive removal of phenol and aniline by modified bentonite: adsorption isotherm and kinetics study. Appl. Water Sci. 2018;8:170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bazarafshan E., Ahmadi S. Efficiency of combined processes of coagulation and modified activated bentonite with sodium hydroxide as a biosorbent in the final treatment of leachate: kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Health Res. Commun. 2017;3 6-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoshnamvand N., Ahmadi S., Mostafapour F.K. Kinetic and isotherm studies on ciprofloxacin adsorption using magnesium oxide nanoparticles. J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2017;7:079–083. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igwegbe C.A., Onyechi P.C., Onukwuli O.D., Nwokedi I.C. Adsorptive treatment of textile wastewater using activated carbon produced from Mucuna pruriens seed shells. World J. Eng. Technol. 2016:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Igwegbe C.A., Banach A.M., Ahmadi S. Adsorption of Reactive Blue 19 from aqueous environment on magnesium oxide nanoparticles: kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. Pharm. Chem. J. 2018;5:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salaryan P., Mokari F., Saleh Mohammadnia M., Khalilpour M. The survey of linear and non-linear methods of pseudo-second-order kinetic in adsorption of Co (II) from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Water Wastewater Treat. 2013;1:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmadi Sh., Kord Mostafapour F. Tea wastes as a low cost adsorbent for the removal of COD from landfill leachate: kinetic study. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2017;4:103–164. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafshejani L.D., Tangsir S., Daneshvar E., Maljanen M., Lähde A., Jokiniemi J., Naushad M., Bhatnagar A. Optimization of fluoride removal from aqueous solution byAl2O3 nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;238:254–262. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyah Y., Lahrichi A., Idrissi M., Boujraf S., Taouda H., Zerrouq F. Assessment of adsorption kinetics for removal potential of Crystal Violet dye from aqueous solutions using Moroccan pyrophyllite. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017;23:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber W.J., Morris J.C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. Am. Soc. Civil Eng. 1963;89:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igwegbe C.A., Onukwuli O.D., Nwabanne J.T. Adsorptive removal of vat yellow 4 on activated Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean) seed shells carbon. Asian J. Chem. Sci. 2016;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]