Abstract

Background

Yokose virus was first isolated from bats (Miniopterus fuliginosus) collected in Yokosuka, Japan, in 1971, and is a new member of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. In this study, we isolated a Yokose virus from a serum sample of Myotis daubentonii (order Chiroptera, family Vespertilionidae) collected in Yunnan province, China in 2013.

Methods

The serum specimens of bat were used to inoculate in BHK-21 and Vero E6 cells for virus isolation. Then the viral complete genome sequence was obtained and was used for phylogenetic analysis performed by BEAST software package.

Results

The virus was shown to have cytopathic effects in mammalian cells (BHK-21 and Vero E6). Genome sequencing indicated that it has a single open reading frame (ORF), with a genome of 10,785 nucleotides in total. Phylogenetic analysis of the viral genome suggests that XYBX1332 is a Yokose virus (YOKV) of the genus Flavivirus. Nucleotide and amino acid homology levels of the ORF of XYBX1332 and Oita-36, the original strain of YOKV, were 72 and 82%, respectively. The ORFs of XYBX1332 and Oita-36 encode 3422 and 3425 amino acids, respectively. In addition, the non-coding regions (5′- and 3′-untranslated regions [UTRs]) of these two strains differ in length and the homology of the 5′- and 3′-UTRs was 81.5 and 78.3%, respectively.

Conclusion

The isolation of YOKV (XYBX1332) from inland China thousands of kilometers from Yokosuka, Japan, suggests that the geographical distribution of YOKV is not limited to the islands of Japan and that it can also exist in the inland areas of Asia. However, there are large differences between the Chinese and Japanese YOKV strains in viral genome.

Keywords: Yokose virus, Bat, China

Background

The Flavivirus includes 70 members [1], etc., many of which, including Japanese encephalitis virus [2], dengue virus [3], West Nile virus [3], yellow fever virus [4], and Zika virus [5], which can cause some human severe diseases [6]. Flaviviruses have introduced a substantial disease burden in humans and animals around the world, and, as mosquito-borne viruses, can spread widely [6, 7].

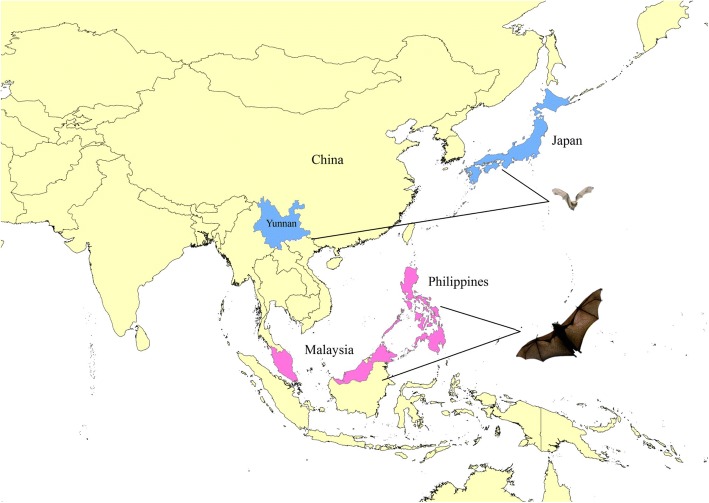

Yokose virus (YOKV) belongs to the Flavivirus, which was first isolated from bats (Miniopterus fuliginosus) collected in Yokosuka, Japan, in 1971, and the first YOKV strain isolated was Oita-36 (Fig. 1). Sequencing results indicate that the YOKV genome is 10,857 nucleotides (nt) in total [8]. Like other flaviviruses, YOKV has only one open reading frame (ORF), which encodes 3425 amino acids. The genome encodes three structural proteins, the capsid (C), membrane (M), and envelope (E) proteins, as well as seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5). There are 5′ and 3′ non-coding regions at the ends of the genome. Molecular genetic analysis indicated that YOKV is a new member of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus [8]. Furthermore, YOKV is genetically related to other flaviviruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and West Nile virus. YOKV is closely related to yellow fever virus, which both clustered in the same clade [8]. Additionally, YOKV was neutralized by antisera to individuals inoculated with yellow fever virus vaccine. The above results suggested that this new member of flavivirus is genetically related to yellow fever virus. A serological survey of YOKV in the Philippines and Malaysia showed that the YOKV antibody was detected in the serum of bats (Rousettus leschenaultii), suggesting that the distribution of YOKV was not limited to Yokosuka Island, Japan [9] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Isolation of Yokose virus (YOKV) and distribution of areas positive for the YOKV antibody. YOKV was isolated from microbats in Japan and China (the blue areas), and YOKV antibodies were detected in the serum of fruit bats in Malaysia and Philippines (the pink areas)

In this study, we isolated a virus (XYBX1332) from a serum sample of Myotis daubentonii (order Chiroptera, family Vespertilionidae) collected in the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau Region (average altitude 2000–4000 m) in the southwest of China in July 2013. XYBX1332 was identified as YOKV using whole-genome sequencing. However, our study indicated some clear differences in molecular biology between XYBX1332 and the original isolate of YOKV.

Methods

Sample collection

The bat specimens were collected in Xiangyun County of Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province (100.32°E, 25.28°N). Sticky nets were placed at the outlet of the cave in the evening. Once trapped, the bats were classified according to the morphological characteristics. The bats were released after the blood samples were collected. The blood samples were kept in − 80°[10].

Cell lines and virus isolation

Baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells were stored in the laboratory. The cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin combination, 1% glutamine, and 2% NaHCO3 (pH 7.4) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. African green monkey kidney cells (Vero E6) were cultured in a similar manner [10–12].

The serum specimens of bat were diluted 1:50 and inoculated in monolayered BHK-21 and Vero E6 cells, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were observed daily for cytopathic effects (CPEs). [10, 11].

Viral RNA extraction

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μl of culture supernatant of XYBX1332 cultured in BHK-21 cells using a QIAamp Viral RNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Then, cDNA was generated by reverse transcription using Ready-to-Go™ You Prime First-Strand Beads (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Total RNA was extracted from the culture supernatant of BHK-21 cells infected with XYBX1332 and a cDNA library was generated by reverse transcription. Then, primers specific for Alphavirus, Flavivirus, and Bunyavirus were used to perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification (Table 1). PCR products were detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis [13–15].

Table 1.

Arbovirus-specific primers used for amplification in this study

| Sequence of primers(5′-3′) | Amplify region | Length of product | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavivirus | ||||

| FU1 | TACCACATGATGGGAAAGAGAGAGAA | NS5 | 310 | 13 |

| CFD2 | GTGTCCCAGCCGGCGGTGTCATCAGC | |||

| Alphavirus | ||||

| M2W | YAGAGCDTTTTCGCAYSTRGCHW | NS1 | 434/310 | 13 |

| cM3 W | ACATRAANKGNGTNGTRTCRAANCCDAYCC | |||

| M2 W2 | TGYCCNVTGMDNWSYVCNGARGAYCC | |||

| Bunyavirus | ||||

| BUP | ATGACTGAGTTGGAGTTTGATGTCGC | S | 251 | 13, 14 |

| BDW | TGTTCCTGTTGCCAGGAAAAT | |||

Viral genome sequencing

The target gene fragment of XYBX1332 was amplified using the designed primers (Primer 5.0 software; Table 2). Amplified products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis (1%), purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and sequenced directly [10, 13, 14].

Table 2.

Primers designed for XYBX1332

| Primers | Sequences (5′ - 3′) | Sites |

|---|---|---|

| Yok-F1 | 5’ TTTGCGTGCTAGTCGCTGAG 3’ | 9–37 |

| Yok-R1 | 5’ TATCCTTTGCCGTAAGAGTGA 3’ | 1119–1139 |

| Yok-F2 | 5’ CCCTGCATACAGCACTCATT 3’ | 995–1014 |

| Yok-R2 | 5’ GCCTTTCATTGTCAGTCCCT 3’ | 1880–1898 |

| Yok-F3 | 5’ GGCTGGAGCTACTAGAATTACG 3’ | 1781–1803 |

| Yok-R3 | 5’ TCACTGATGCTATTTCCCTTG 3’ | 2613–2633 |

| Yok-F4 | 5’ AGGCGTGAAATCAAGTGT 3’ | 2505–2422 |

| Yok-R4 | 5’ CATACCAGCATTCATT 3’ | 3459–3474 |

| Yok-F5 | 5’ CAGTAAGAGGGGACCATCAGT 3’ | 3353–3573 |

| Yok-R5 | 5’ ATAGCACAGCAATAGCACAGAA 3’ | 4356–4377 |

| Yok-F6 | 5’ TGGAATGACGGTGATAGGAG 3’ | 4238–4257 |

| Yok-R6 | 5’ GGCAATGGCTGAAACAAAT 3’ | 5120–5138 |

| Yok-F7 | 5’ ATAGTCAACAAACAAGGGGAAGT 3’ | 5037–5059 |

| Yok-R7 | 5’ CAGAGGAAGCAGTTATTGGAAGT 3’ | 5976–5998 |

| Yok-F8 | 5’ TACCCGTGGAAAGAGTGATAGA 3’ | 5869–5890 |

| Yok-R8 | 5’ GCATAGAATAAAGAAGACAAGCATA 3’ | 6815–6839 |

| Yok-F9 | 5’ CCAGGATGACATTGGCTTTT 3’ | 6703–6720 |

| Yok-R9 | 5’ CAGCAGCACCGTCTTGGA 3’ | 7819–7836 |

| Yok-F10 | 5′ AGGTGAGATGTGGAAGAAGGA 3’ | 7700–7720 |

| Yok-R10 | 5’ AGGAGCGGTATGGGTGG 3’ | 8586–8602 |

| Yok-F11 | 5’ GATTCAGGGACCAGAAGTGTT 3’ | 8454–8474 |

| Yok-R11 | 5’ CTCCTTTCAATGGTCTTTCAACTCT 3’ | 9438–9462 |

| Yok-F12 | 5’ TCTTGGCTGAAGCGGTAAT 3’ | 9367–9385 |

| Yok-R12 | 5’ CAGACTCTATTCCATACATCAAGC 3’ | 10,135–10,158 |

| Yok-F13 | 5’ CGATCAATTCTTCAGTGCCAATA 3’ | 10,018–10,040 |

| Yok-R13 | 5’ CGTCCAAACAAGAGGAAAAT 3’ | 10,526–10,545 |

Sequence amplification of non-coding regions

The 5′ and 3′-UTR sequences were amplified using RACE System Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends Kit (Invitrogen), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences obtained were used to assemble a complete genome sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences of typical strains of Flavivirus isolated from different hosts in various years and countries were downloaded from GenBank (Table 3). The SeqMan in DNASTAR was used for sequence assembly and quality analysis. The homology analysis and alignment of nucleotide and amino acid sequences were conducted using BioEdit (version 7.0.5.3) and ClustalX 1.8 software. Analysis of differences in the nucleotide and amino acid sequences was conducted using GeneDOC software [10, 13, 14].

Table 3.

Sequences used for phylogenetic analysis in this study

| Virus | Strain | Year | Country | Source | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | Ishikawa | 1994 | Japan | Swine | AB051292 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | FU | 1995 | Australia | Human serum | AF217620 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | p3 | 1949 | China | Human brain | U47032 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | JKT6468 | 1981 | Indonesia | Culex tritaeniorhynchus | AY184212 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | Muar | 1952 | Malaysia | Human brain | HM596272 |

| Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV) | MVE-1-51 | 1951 | Australia | Human brain | NC_000943 |

| West Nile virus (WNV) | ArB3573/82 | Central African Republic | DQ318020 | ||

| Kunjin virus (KUNV) | MRM61C | Australia | Mosquito | D00246 | |

| St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) | Kern217 | USA | Mosquito | DQ525916 | |

| Zika virus | MR766-NIID | 1947 | Uganda | Monkey | LC002520 |

| Zika virus | ZikaSPH2015 | 2015 | Brazil | Human | KU321639 |

| Dengue virus 4 (DENV4) | 341,750 | 1982 | Colombia | Human | GU289913 |

| Dengue virus 2 (DENV2) | D2/SG/05K4155DK1/2005 | 2005 | Singapore | Human blood | EU081180 |

| Dengue virus 1 (DENV1) | SG(EHI)D1227Y03 | 2003 | Singapore | FJ469909 | |

| Dengue virus 3 (DENV3) | D3/H/IMTSSA-MART/1999/1243 | 1999 | Martinique (French West Indies) | Human blood | AY099337 |

| Yellow fever virus (YFV) | YFV17D | X03700 | |||

| Yokose virus(YOKV) | XYBX1332 | 2013 | China | Bat | – |

| Yokose virus(YOKV) | Oita-36 | 1971 | Japan | Bat | AB114858 |

| Powassan virus (POWV) | Spassk-9 | 1975 | Russia | Dermacentor silvarum (tick) | EU770575 |

| Langat virus (LANV) | TP21 | Tick | NC_003690 | ||

| Louping ill virus (LIV) | 369/T2 | UK | NC_001809 | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) | Toro-2003 | 2003 | Sweden: Toro | Ixodes ricinu | DQ401140 |

| Culex flavivirus | Tokyo | 2003 | Japan | Culex pipiens | AB262759 |

Nucleotide sequence phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using Markov chain Monte Carlo analysis implemented in the BEAST software package (version 1.8.4; http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/). The analysis was performed using the generalized time reversible substitution model with gamma distributed rate variation among sites and using default priors. The Markov chains were run for 10 million generations, with the first 10% of samples discarded as burn-in. Convergence of parameters was verified using Tracer v1.4 and indicated as effective sample size (ESS > 200). A maximum clade credibility tree was summarized using TreeAnnotator, which annotates all nodes with posterior probability support values [16].

Results

Virus isolation

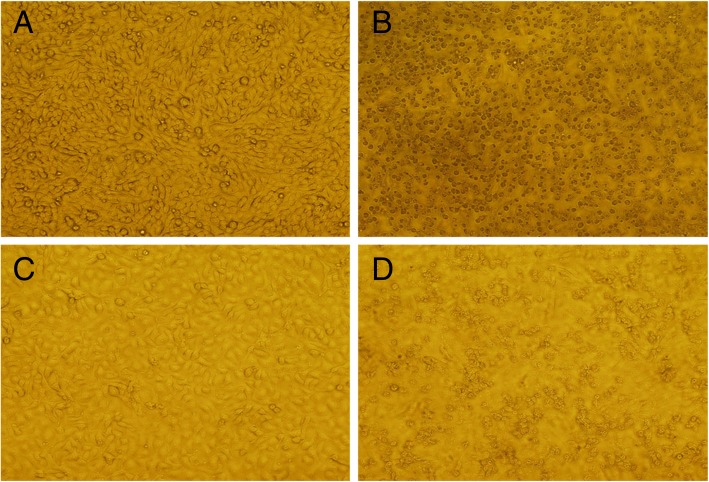

Both BHK-21 and Vero E6 cells inoculated with serum specimen numbered XYBX1332 exhibited obvious CPEs, which included rounding up, aggregation, and exfoliation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cytopathic effects (CPEs) of XYBC1332 in BHK-21 and Vero E6 cells. a) Control uninfected BHK-21 cells. b) Infected BHK-21 cells at 4 days post-infection. c) Control uninfected Vero E6 cells. d) Infected Vero E6 cells at 5 days post-infection

Virus identification

The results showed that PCR products were detected with Flavivirus-specific primers, while no amplification was detected with primers specific for Alphavirus and Bunyavirus, suggesting that XYBX1332 is a Flavivirus.

Viral genome sequencing and homology analysis

To determine the molecular characteristics of XYBX1332, the whole genome of XYBX1332 was amplified using 13 pairs of primers (Table 2) and sequenced (GenBank accession no. MH051229).

The Open Reading Frame (ORF) of XYBX1332 is 10,266 nt (excluding the 5′ and 3′-UTRs), which encodes 3422 amino acids and 10 protein-coding genes. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence information is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Open Reading Frame (ORF) Genome homology of the XYBX1332, Oita-36 and YFV17D

| Protein | XYBX1332 | Oita-36 | YFV17D | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nta | aab | %c | ntd | %e | aaf | % g | nth | % i | aaj | |

| C | 378 | 126 | 71 | 384 | 69 | 128 | 49 | 363 | 34 | 121 |

| PrM | 504 | 168 | 71 | 504 | 79 | 168 | 44 | 492 | 47 | 164 |

| E | 1470 | 490 | 74 | 1470 | 83 | 490 | 57 | 1479 | 49 | 493 |

| NS1 | 1059 | 353 | 76 | 1059 | 86 | 353 | 57 | 1056 | 53 | 352 |

| NS2A | 684 | 228 | 60 | 681 | 66 | 227 | 46 | 672 | 26 | 224 |

| NS2B | 390 | 130 | 54 | 390 | 79 | 130 | 26 | 390 | 32 | 130 |

| NS3 | 1860 | 620 | 73 | 1860 | 85 | 620 | 59 | 1869 | 54 | 623 |

| NS4A | 447 | 149 | 72 | 447 | 83 | 149 | 47 | 447 | 36 | 149 |

| NS4B | 756 | 252 | 71 | 762 | 83 | 254 | 53 | 750 | 44 | 250 |

| NS5 | 2718 | 906 | 74 | 2718 | 85 | 906 | 61 | 2715 | 62 | 905 |

| ORF | 10,266 | 3422 | 72 | 10,275 | 82 | 3425 | 54 | 10,233 | 51 | 3411 |

XYBX1332 is the strain isolated in this study. Oita-36 and YFV17D are the reference viruses. GENETYX Ver.11 software was used in the comparison of nucleotide and amino acid sequence length in the region. a and b represent the nucleotide sequence length (nt.) and amino acid sequence length (aa.) of XYBX1332 respectively; d, f represents Oita-36 length of nt. and aa. respectively; h, j represents YFV17D length of nt. and aa. respectively. c and e represent homology of nucleotide and amino acid between XYBX1332 and Otia-36. g and i represent homology of nucleotide and amino acid between XYBX1332 and YFV17D

Compared with other flaviviruses, YOKV shared the highest homology with yellow fever virus [8]. Therefore, we determined the nucleotide and amino acid homology of YOKV (Oita-36 strain), yellow fever virus (YFV17D strain) and XYBX1332. The analysis showed that the nucleotide homology of XYBX1332 and Oita-36 ranged from 54 to 76%, meanwhile the amino acid homology ranged from 66 to 86%. The nucleotide and amino acid homology levels of the coding region between these two viruses were 72 and 82%, respectively. The nucleotide and amino acid homology levels of XYBX1332 with YFV17D were in the ranges of 26–63% and 26–62%, respectively. The nucleotide and amino acid homology levels of the coding regions of XYBX1332 and YFV17D were 54 and 51%, respectively. Further analysis revealed differences in the number of amino acids encoded by XYBX1332 and Oita-36 in the C gene (XYBX1332/Oita-36: 126/128), NS2A gene (228/227), and NS4B gene (252/254). The homology of XYBX1332 and Oita-36 is shown in Table 4.

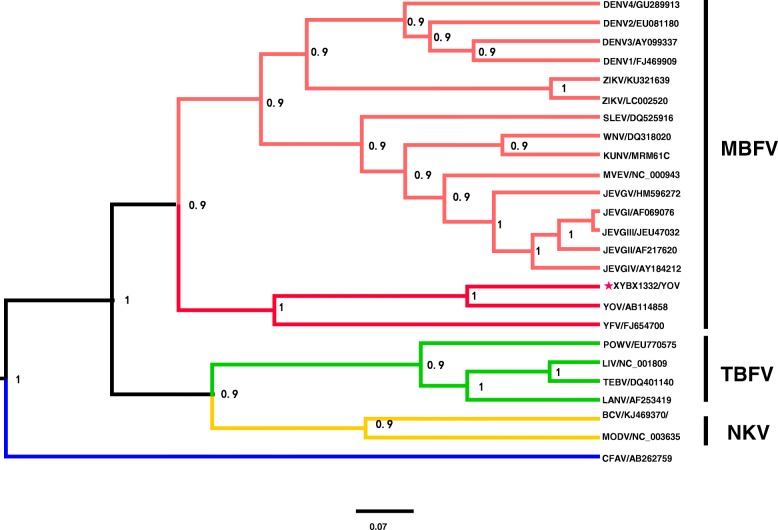

Phylogenetic analysis

To understand the molecular genetic evolution of XYBX1332, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted based on the ORF sequences of XYBX1332 and 23 other strains of flavivirus (including mosquito- and tick-borne viruses; Table 3). The results suggested that these strains could be divided into three evolutionary branches. The first branch contained 18 strains of mosquito-borne flavivirus, including Japanese encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, Dengue virus, and Zika virus, while four tick-borne virus strains, including tick-borne encephalitis virus and Powassan virus, were grouped in the second branch. The third branch incorporated only one strain, a Culex flavivirus isolated in Tokyo in 2003 (Fig. 3). XYBX1332 isolated from bats in this study shared the same evolutionary branch as YOKV (Oita-36) isolated in Yokosuka, Japan, along with other mosquito-borne viruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus.

Fig. 3.

Bayesian phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus based on open reading frame gene nucleotide sequence. Posterior probability values of each cluster are shown to the right of the nodes. The mosquito-borne, tick-borne, and no known-vector flaviviruses (MBFV, TBFV, and NKV, respectively) are labeled in red, green, and yellow, respectively. The newly isolated virus in our study is indicated with a red star. Scale bars indicate the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

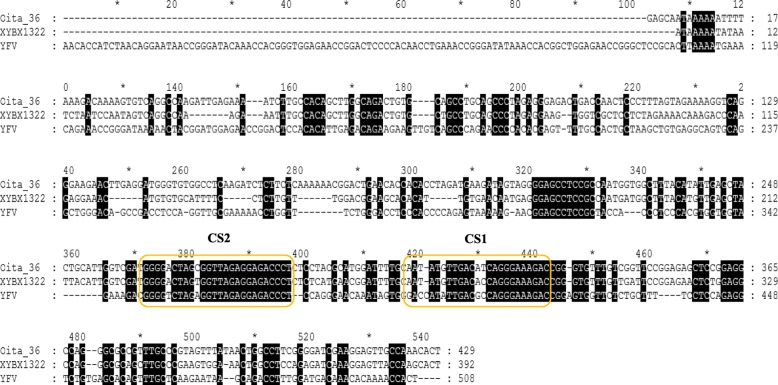

5′- and 3′-UTR sequences

The 5′ and 3′-UTR sequences were amplified using RACE System Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends Kit. Sequencing of the non-coding region of XYBX1332 showed that the lengths of its 5′- and 3′-UTR sequences are 124 and 395 nt, respectively. Furthermore, the length of the 5′-UTR of XYBX1332 is 26 nt shorter than that of Oita-36 (23 and 3 base deletions at loci 63–86 and 122–123, respectively); while the 3′-UTR sequence is 37 nt shorter than that of Oita-36 (12, 19, and 5 base deletions at loci 10,444–10,460, 10,574–10,592, and 10,595–10,599, respectively). The 5′-UTR sequence of XYBX1332 exhibited 81.5 and 35.6% homology with Oita-36 and YFV17D, and there was 78.3 and 16.6% homology for the 3’-UTR sequence, respectively (Table 5 and Fig. 4). Additionally, compared with Oita-36, one base mutation (C > T) occurred in CS2, one of two conserved motifs in the 3′-UTR sequence of XYBX1332 (Fig. 5).

Table 5.

5′- and 3′-untranslated region (UTR) Genome homology of the XYBX1332, Oita-36 and YFV17D

| XYBX1322 | Oita-36 | YFV17D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nta | ntb | %d | ntc | %e | |

| 5’-UTR | 124 | 150 | 81.5 | 118 | 35.6 |

| 3’-UTR | 395 | 432 | 78.3 | 508 | 16.6 |

XYBX1332 is the strain isolated in this study. Oita-36 and YFV17D are the reference viruses. Percent identity value calculated based on alignment. a, b and c represent the nucleotide sequence length (nt.) of XYBX1332, Otia-36 and YFV17D respectively. d represents homology of nucleotide between XYBX1332 and Otia-36. e represents homology of nucleotide between XYBX1332 and YFV17D

Fig. 4.

5′-UTR sequence of XYBX1332

Fig. 5.

3′-UTR sequence of XYBX1332. The yellow boxes indicate the two conserved motifs, CS1 and CS2

Discussion

In this study, the virus XYBX1332 was isolated from bat specimens collected in Yunnan Province, mainland China. This virus was identified as a YOKV in the genus Flavivirus based on phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3). However, some clear differences between XYBX1332 and the original strain of YOKV (Oita-36) were identified as following.1) As mentioned above, the genome length of Oita-36 (including the 5′- and 3′-UTRs) is 10,857 nt, while that of XYBX1332 is 10,785 nt. 2) The coding region of Oita-36 is 10,275 nt, which encodes 3425 amino acids; The coding region of XYBX1332 is 10,266 nt, which encodes 3422 amino acids (Table 4). 3) The two viruses of ORF region exhibited 72 and 82% nucleotide and amino acid homology, respectively.4) The lengths of the 5′-UTR for XYBX1332 and Oita-36 are 124 and 150 nt, respectively, while those of the 3′-UTR are 395 and 432 nt, respectively. The homology of the 5′- and 3′-UTR sequences between the two strains was determined to be 81.5 and 78.3%, respectively (Table 5).5) It is only 74% of the nucleotide homology in the 3’end of NS5 gene between XYBX1332 virus and Oita-36 virus (Table 4), which is much lower than cut-off (84%) of that between species of Flavivirus[17]. These results suggested that, although XYBX1332 is a YOKV based on phylogenetic analysis, it may be a new virus in Flavivirus. Furthermore, the cross-neutralization test between XYBX1332 virus and Oita-36 virus would be conducted by the antigenicity between the viruses to confirm whether the XYBX1332 virus is a new species in Flavivirus.

As mentioned earlier, YOKV (Oita-36) was first isolated from a bat (M. fuliginosus) in Japan, while XYBX1332 was isolated from the serum of M. daubentonii. Although the strains were isolated from different bat species, Miniopterus fuliginosus (Miniopterus, Miniopteridae) and Myotis daubentonii (Myotis, Vespertilioninae), both species belong to the suborder Microchiroptera of the order Chiroptera [18]. The isolation of YOKVs from microbats on two separate occasions suggests that microbats may be suitable hosts for YOKV, although the YOKV replicates poorly in the fruit bat [9].

Bats are mammals that can fly and are characterized by a large number of species and wide distribution. Many studies have shown that bats can carry and spread a variety of pathogens that can cause human and animal disease [19], including SARS [20], Ebola virus [21], and influenza virus [22]. After years of monitoring, a large number of recombinant coronaviruses were discovered in bats, further suggesting that bats may be the host animal for SARS [23]. Given that Oita-36 and XYBX1332 were isolated from the serum of bats, it has been suggested that YOKV can exist in bats, may be occasionally in the long term. How is the virus transmitted to bats? In recent years, Kaeng Khoi virus [10], Orthoreovirus [24], Bunyavirus [25], and Rhabdovirus [26] have been isolated from bat flies (Eucampsipoda sundaica), an ectozoon that resides on bats. Whether a cycle including bat flies or other blood-sucking insects (vectors) and bats (hosts) present in the wild to maintain and spread YOKV will require further studies.

Conclusion

The isolation of YOKV (XYBX1332) from inland China thousands of kilometers from Yokosuka, Japan, suggests that the geographical distribution of YOKV is not limited to the islands of Japan and that it can also exist in the inland areas of Asia. However, there are large differences between the Chinese and Japanese YOKV strains in viral genome.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.81290342,31560049), Yunnan Province Applied Basic Research Projects (No.2016FB029), The National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1201904), Development Grant of State Key Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control (No.2014SKLID103).

Availability of data and materials

Sequence data obtained in this study is available in the GenBank (accession no. MH051229).

Authors’ contributions

YF, SF, HZ, WY, YZ, and GL conceived and designed the study. YF, XR, ZX, and SF collected samples and performed the laboratory work. YF, XR, and ZX analyzed the data. YF, XR, ZX, XL, and GL wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research, including the procedures and protocols of specimen collection and processing, was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Yunnan Institute of Endemic Diseases Control and Prevention.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yun Feng, Email: ynfy428@163.com.

Xiaojie Ren, Email: xiaojieren0610@outlook.com.

Ziqian Xu, Email: robert3036@163.com.

Shihong Fu, Email: shihongfu@hotmail.com.

Xiaolong Li, Email: xlli1630@hotmail.com.

Hailin Zhang, Email: zhanghl715@163.com.

Weihong Yang, Email: yangwh0604@163.com.

Yuzhen Zhang, Email: second7368@163.com.

Guodong Liang, Email: gdliang@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Lindenbach BD, Thiel HJ, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: the vireses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology[M]. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer-Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 1102-1153.

- 2.Erlanger TE, Weiss S, Keiser J, Utzinger J, Wiedenmayer K. Past, present, and future of Japanese encephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1501.080311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S98–109. doi: 10.1038/nm1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grobbelaar AA, Weyer J, Moolla N, Jansen van Vuren P, Moises F, Paweska JT. Resurgence of Yellow Fever in Angola, 2015–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1854–1855. doi: 10.3201/eid2210.160818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antivir Res. 2010;85:328–345. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould E, Pettersson J, Higgs S, Charrel R, de Lamballerie X. Emerging arboviruses: Why today? One Heal. 2017;4:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajima S, Takasaki T, Matsuno S, Nakayama M, Kurane I. Genetic characterization of Yokose virus, a flavivirus isolated from the bat in Japan. Virology. 2005;332:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe S, Omatsu T, Miranda MEG, Masangkay JS, Ueda N, Endo M, et al. Epizootology and experimental infection of Yokose virus in bats. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;33:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Y, Li Y, Fu S, Li X, Song J, Zhang H, et al. Isolation of Kaeng Khoi virus (KKV) from Eucampsipoda sundaica bat flies in China. Virus Res. 2017;238:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei W, Guo X, Fu S, Feng Y, Nie K, Song J, et al. Isolation of Tibet orbivirus, TIBOV, from culicoides collected in Yunnan, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0139646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Z, Fu SH, Cao L, Tang CJ, Zhang S, Li ZX, et al. Human infection with West Nile Virus, Xinjiang, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1421–1423. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.131433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Zhang H, Sun X, Fu S, Wang H, Feng Y, et al. Distribution of mosquitoes and mosquito-borne arboviruses in Yunnan Province near the China-Myanmar-Laos border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:738–746. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuno G, Mitchell CJ, Chang GJJ, Smith GC. Detecting bunyaviruses of the Bunyamwera and California serogroups by a PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1184–1188. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1184-1188.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li M, Zheng Y, Zhao G, Fu S, Wang D, Wang Z, et al. Tibet Orbivirus, a novel Orbivirus species isolated from Anopheles maculatus mosquitoes in Tibet, China. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, Gould EA, Meyers G, Monath T, Muerhoff S, Pletnev A, Rico-Hesse R, Smith DB, Stapleton JT, ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017;98:2–3 https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Teeling EC. Bat (Chiroptera). The Timetree of Life. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV, Schountz T. Bats: Important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, et al. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438:575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong S, Li Y, Rivailler P, Conrardy C, Castillo DAA, Chen LM, et al. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116200109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu B, Zeng LP, Lou YX, Ge XY, Zhang W, Li B, et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen van Vuren P, Wiley M, Palacios G, Storm N, McCulloch S, Markotter W, et al. Isolation of a Novel Fusogenic Orthoreovirus from Eucampsipoda africana Bat Flies in South Africa. Viruses. 2016;8:65. doi: 10.3390/v8030065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen Van Vuren P, Wiley MR, Palacios G, Storm N, Markotter W, Birkhead M, et al. Isolation of a novel orthobunyavirus from bat flies (Eucampsipoda africana) J Gen Virol. 2017;98:935–945. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg TL, Bennett AJ, Kityo R, Kuhn JH, Chapman CA. Kanyawara Virus: A Novel Rhabdovirus Infecting Newly Discovered Nycteribiid Bat Flies Infesting Previously Unknown Pteropodid Bats in Uganda. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5287. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05236-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data obtained in this study is available in the GenBank (accession no. MH051229).