Abstract

Research examining associations between self-reported experiences of discrimination overall (e.g. potentially due to race, gender, socioeconomic status, age, etc…) and health –particularly among African-Americans – has grown rapidly over the past two decades. Yet recent findings suggest that self-reported experiences of racism alone may be less impactful for the health of African-Americans than previously hypothesized. Thus, an approach that captures a broader range of complexities in the study of discrimination and health among African-Americans may be warranted. This article presents an argument for the importance of examining intersectionalities in studies of discrimination and physical health in African-Americans, and provides an overview of research in this area.

Discrimination and the Health of African-Americans

On almost every major indicator of physical health (e.g. coronary heart disease, cancer, stroke, HIV), African-Americans fare worse than individuals from other racial/ethnic backgrounds in the United States (Cunningham, et al., 2017). This excess burden has been documented for decades, and is not completely explained by socioeconomic status (SES), health behaviors, or access to care (Williams, 2012). Consequently, a number of researchers have argued that discriminatory stressors may be one important pathway through which “race” impacts physical health outcomes among African-Americans (Lewis, Cogburn, & Williams, 2015; Williams, 2012).

Discrimination is defined as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of a person or group of people, particularly on the grounds of characteristics such as race, age, or gender. Across studies, African-Americans report more discrimination and unfair treatment than other racial/ethnic groups (Everson-Rose, et al., 2015; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Lewis, et al., 2013) and despite progress since the 1960’s, objective evidence suggests that discrimination remains a significant problem in the United States in housing (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015), policing (U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, 2017), and medical care (Chen & Li, 2015).

Research has documented linkages between self-reported experiences of discrimination overall (e.g. potentially due to race, gender, SES, age, sexual orientation) and objective physical health outcomes across diverse groups (Beydoun, et al., 2017; Chae, Drenkard, Lewis, & Lim, 2015; Everson-Rose, et al., 2015; Lewis, et al., 2013). However, findings linking reports of “racism” alone to physical health—particularly among African-Americans–have been mixed. In a recent review and meta-analysis, Paradies (2015) found that associations between reports of racism (e.g. discrimination solely on the basis of race) and physical health were weakest for African-Americans, compared to Latino(a)s and Asian-Americans. This is in contrast to prior meta-analytic findings, which focused on reports of discrimination overall and found similar (Pascoe & Richman, 2009), and in some instances more pronounced (Dolezsar, McGrath, Herzig, & Miller, 2014) associations among African-Americans compared to other groups. Together, these findings suggest that studies that focus on assessing experiences of racism exclusively might underestimate the overall impact of discriminatory stressors on the health of African-Americans. Thus, an approach that captures a broader range of complexities may be warranted.

The Role of “Intersectionalities” and the Importance of Looking Within African-Americans

One major limitation of prior research on discrimination and health in African-Americans is the tendency to focus on African-Americans as a monolith in 1) questionnaires assessing discrimination, 2) the composition of study participants, and 3) the analysis plan. Some of this is due to the desire to compare across racial/ethnic groups, to better understand racial/ethnic disparities in health. However, this approach precludes an examination of how heterogeneity within the African-American population (e.g. age, gender, SES, sexual orientation, etc…) might impact exposure to discrimination, and associations between discrimination and physical health.

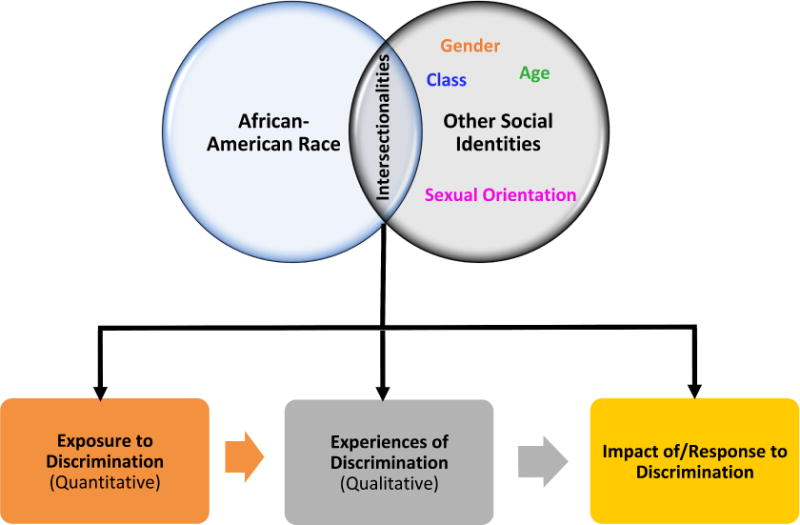

In 1989 Crenshaw argued that: “Black women sometimes experience discrimination in ways similar to white women’s experiences; sometimes they share very similar experiences with Black men. Yet often they experience double discrimination–the combined effects of practices [that] discriminate on the basis of race, and on the basis of sex. And sometimes, they experience discrimination as Black women—not the sum of race and sex discrimination, but as Black women” (1989) p 149. The terminology used to describe this combining of effects– “intersectionalities”– has been most frequently employed to characterize the experiences of African-American women (Crenshaw, 1989; Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008); however researchers have noted the advantage of this approach for understanding the experiences of African-American men (both gay and straight) and others at the intersection of two or more identities (Bowleg, et al., 2017). The current review is designed to provide an overview and working framework for how intersectionalities might shape exposure to, experiences of, and responses to discrimination among African-Americans (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Discrimination, Intersectionalities and Health among African-Americans.

Note: Figure 1 provides a working framework for how African-American race might interact with other social identities to shape: a) exposure to discrimination (e.g. the quantitative amount of discrimination experienced by different subgroups); b) experiences of discrimination (e.g. qualitative differences in how discrimination might be experienced by individuals with different intersecting identities) and c) the physiological (or psychological) impact of or response to discrimination.

Discrimination, Gender, and Health among African-Americans

Gender is perhaps the most frequently examined aspect of intersectional identity in research on discrimination among African-Americans. Consistent with Crenshaw’s (1989) original premise, in a study of 144 adults Kwate and Goodman (2015) found that the forms of discrimination reported by African-American women were both quantitatively and qualitatively different from those reported by African-American men. For example, African-American women were more likely than African-American men to report interpersonal incivilities, while African-American men reported more major experiences of discrimination, in particular experiences with police, and criminal profiling, than African-American women (Kwate & Goodman, 2015). Some of these differences could be due to the types of major discriminatory experiences assessed (e.g. wage discrimination, which disproportionately impacts African-American women relative to African-American men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015) was not queried). Still, Kwate & Goodman’s findings are consistent with objective reports from the Department of Justice (2017), documenting biased policing against African-American men relative to White men and women of all racial/ethnic backgrounds at multiple levels–including routine stops, arrests, and use of excessive (lethal and non-lethal) force (U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, 2017). Collectively, these findings provide support for Sidanius’ subordinate male target hypothesis (SMTH), which posits that men, rather than women, are the primary targets of discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities (Navarrete, McDonald, Molina, & Sidanius, 2010).

However, studies of discrimination and objective, physiological indicators of health have not observed stronger associations in African-American men, relative to African-American women. In fact, the few studies that have documented gender differences in discrimination and physical health associations have found that effects are more pronounced for African-American women, compared to African-American men (Beydoun, et al., 2017; Richman & Jonassaint, 2008; Roberts, Vines, Kaufman, & James, 2008). This could be a result of “double discrimination” as detailed by Crenshaw (1989); the relative underrepresentation of African-American men in studies of discrimination and physical health; overall gender differences in vulnerability to stress (Bourke, Harrell, & Neigh, 2012) and sensitivity to social rejection (Stroud, Salovey, & Epel, 2002); or the use of scales that rely heavily on everyday experiences and interpersonal incivilities, which may be more relevant for African-American women (Kwate & Goodman, 2015). Although scholars have begun designing questionnaires to capture experiences occurring at the juncture of race and gender (English, et al., 2017; Lewis & Neville, 2015), the effects of these uniquely intersectional experiences (e.g. derogatory comments about African-American women’s bodies; African-American men’s experiences with police) have yet to be determined. Thus, while the extant literature suggests that gender matters in terms of how African-Americans experience discrimination, whether and under what circumstances discrimination might differentially impact the health of African-American women versus African-American men (or vice versa) remains an area of research ripe for further exploration.

Discrimination, SES, and Health among African-Americans

Although the intersectionality framework has historically been used to characterize the experiences of groups at the intersection of two marginalized identities (e.g. African-American and woman), it is also helpful in thinking about intersections between disadvantaged and privileged statuses (Cole, 2009). For example, African-American men occupy at least one disadvantaged and one privileged status, but empirical studies suggest that male status in the context of African-American race is viewed as particularly threatening (Hall, Hall, & Perry, 2016; Plant, Goplen, & Kunstman, 2011), which may be one factor underlying the disproportionate bias African-American men experience in the criminal/legal system, as detailed above. Similarly, middle-class African-Americans have both a disadvantaged and a privileged status, but some have argued that they are frequently unable to access the benefits associated with their privileged SES because of the constraints of their race (Thomas, 2015).

Studies have found that race and SES interact for this group, with higher-SES African-Americans consistently reporting more discrimination than their lower-SES counterparts (Dailey, Kasl, Holford, Lewis, & Jones, 2010; Hunt, Wise, Jipguep, Cozier, & Rosenberg, 2007; Krieger, et al., 2011; NPR, 2017). This is in contrast to other forms of psychosocial stress, which are typically more prevalent among lower-SES groups. Researchers have argued that this is because higher-SES African-Americans are more likely to live, work and socialize in integrated settings than their lower-SES counterparts, thereby increasing their probability of exposure to discrimination (Thomas, 2015). Empirical studies provide support for this hypothesis, documenting greater reports of discrimination from African-Americans living in integrated, versus segregated environments (Dailey, et al., 2010; Hunt, et al., 2007).

Studies examining associations among SES, discrimination, and physical health in African-Americans are limited. However, at least one study has found that the effects of discrimination on cortisol (a physiological marker of stress activation) were more harmful for African-Americans with higher versus lower levels of education (Fuller-Rowell, Doan, & Eccles, 2012). Emerging research on discrimination directly attributed to social class has also highlighted patterns worthy of additional research. A recent study by Van Dyke and colleagues (2017) examined associations between discrimination attributed to social class (i.e. SES discrimination) and C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation linked to later disease, in African-American and White adults. Reports of SES discrimination were associated with higher levels of CRP among college-educated African-Americans, but not African-Americans without a college degree, or Whites at any level of education.

Similar findings were observed in the same cohort examining SES discrimination and sleep quality (Van Dyke, Vaccarino, Quyyumi, & Lewis, 2016). Interestingly, both sets of findings were independent of reports of discrimination due to race and/or gender, suggesting that there may be something uniquely harmful about SES discrimination for African-Americans. For college-educated African-Americans in particular, social class discrimination may function as a direct threat to their ability to access their advantaged SES status, representing a form of expectancy violation (Burgoon, 2009). Expectancy violation theory hypothesizes that when expectations about the social world are violated, disillusionment and negative outcomes result (Negy, Schwartz, & Reig-Ferrer, 2009). This is consistent with arguments presented by Thomas (2015), and further highlights the importance of an intersectional framework in studies of discrimination and health among African-Americans.

The Potential Role of Age

Experimental findings indicate that African-American children (both boys and girls) are often perceived as less “innocent,” and much older than similarly aged white peers beginning as early as age 10, potentially increasing the perception of them as threatening and more liable for their actions (Epstein, Blake, & González, 2017; Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta, & DiTomasso, 2014; Graham & Lowery, 2004). Studies of African-American adolescents have found that reports of discrimination increase in a linear fashion from ages 13 to 17 (Brody, et al., 2014; Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008). Further, in research examining differences across racial/ethnic groups, age-related increases in reports of discrimination –from peers as well as adults—were most pronounced for African-American adolescents compared to those from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006).

In adulthood, young adult and middle-aged African-Americans report significantly higher levels of overall discrimination than African-American adults over the age of 65 (Kessler, et al., 1999; NPR, 2017). It is unclear whether the lower reports of discrimination in older adult African-Americans are a result of selective survival; or represent a cohort effect, with older African-Americans having experienced more traumatic or severe instances of discrimination than most recent scales are designed to assess; or whether older African-American adults (particularly males) are perceived as less threatening than their younger counterparts and are therefore less targeted by discriminatory treatment. These differences could also be driven by age-related processes, such as socio-emotional selectivity, which is the propensity for older adults to self-select out of undesirable social situations (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). Interestingly, despite the considerable body of evidence documenting how age might influence exposure to and experiences of discrimination for African-Americans, few studies have examined the interactive effects of age and discrimination on physical health outcomes in this group.

Finally, while there is a growing body of research examining how experiences of discrimination on the basis of age (e.g. ageism) impact health among older adults, the majority of this research has focused on main effects (Allen, 2016). Thus it is unclear whether associations between ageism and health are more or less pronounced for African-American older adults, compared to older adults from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Further, the extent to which racism and ageism might interact to influence health outcomes in older adults remains underexplored.

Sexual Orientation, Discrimination, and Health in African-Americans

Sexual minorities are one of the most understudied groups in research on discrimination and physical health in African-Americans. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) African-Americans report discrimination on the basis of their sexual minority identity, similar to LGBT individuals from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. However, LGBT African-Americans also report experiencing racism in gay social settings and sexual relationships (Bowleg, et al., 2017). Although there is an emerging body of research linking sexual orientation discrimination to a number of objective health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016), this research has not yet explored whether associations might differ for African-Americans, compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Additional research in this area is clearly warranted.

Summary and Conclusions

This review focused on the potential importance of intersectionalities in the study of discrimination and health, with an emphasis on African-Americans. Because much of the literature on discrimination and health has grown out of a desire to understand the disproportionately high rates of morbidity and mortality observed in this group, we primarily focused on objective physical health outcomes, which are (arguably) more mechanistically linked to disease and mortality than mental health or other self-reported outcomes (Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009). Yet, despite the growing body of research on discrimination and health among African-Americans over the past decades, there remains a limited amount of research examining how within-race differences might pattern associations for this group. Much of this is driven by a continued emphasis on main effects in studies of discrimination and health, and an exclusive focus on discriminatory experiences attributed to racism alone.

Studies have documented how exposure to discrimination differs for African-Americans by a range of demographic and social identities, and while there is preliminary evidence that these intersectionalities also impact associations between discrimination and physical health, additional work in this area is needed. Such explorations might enhance our understanding of factors that contribute to the elevated rates of hypertension in African-American women relative to other race-sex groups; the disproportionately high rates of HIV in African-American men who have sex with men, relative to sexual minorities from other backgrounds; and a range of other physical health conditions shaped by intersectional identities. In this respect, designing studies that acknowledge some of the complexity within race might ultimately lead to a better understanding of factors that shape disparities between races.

References

- Allen JO. Ageism as a Risk Factor for Chronic Disease. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(4):610–614. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun MA, Poggi-Burke A, Zonderman AB, Rostant OS, Evans MK, Crews DC. Perceived Discrimination and Longitudinal Change in Kidney Function Among Urban Adults. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(7):824–834. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke CH, Harrell CS, Neigh GN. Stress-induced sex differences: adaptations mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor. Horm Behav. 2012;62(3):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Del Rio-Gonzalez AM, Holt SL, Perez C, Massie JS, Mandell JE, et al. Intersectional Epistemologies of Ignorance: How Behavioral and Social Science Research Shapes What We Know, Think We Know, and Don’t Know About U.S. Black Men’s Sexualities. J Sex Res. 2017;54(4-5):577–603. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1295300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Lei MK, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SR. Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: a longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Dev. 2014;85(3):989–1002. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon JK. Expectancy violations theory. The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Drenkard CM, Lewis TT, Lim SS. Discrimination and Cumulative Disease Damage Among African American Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2099–2107. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li CI. Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment by Hormone Receptor and HER2 Status. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-15-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989:139–167. Seminal overview of Intersectionality theory. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444–456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey AB, Kasl SV, Holford TR, Lewis TT, Jones BA. Neighborhood- and individual-level socioeconomic variation in perceptions of racial discrimination. Ethn Health. 2010;15(2):145–163. doi: 10.1080/13557851003592561. doi: 921465252 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJ, Miller SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):20–34. doi: 10.1037/a0033718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Bowleg L, del Río-González AM, Tschann JM, Agans RP, Malebranche DJ. Measuring Black Men’s Police-Based Discrimination Experiences: Development and Validation of the Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) Scale. 2017 doi: 10.1037/cdp0000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Blake J, González T. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Alonso A, et al. Perceived Discrimination and Incident Cardiovascular Events: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(3):225–234. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Doan SN, Eccles JS. Differential effects of perceived discrimination on the diurnal cortisol rhythm of African Americans and Whites. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, Jackson MC, Di Leone BAL, Culotta CM, DiTomasso NA. The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2014;106(4):526. doi: 10.1037/a0035663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Lowery BS. Priming unconscious racial stereotypes about adolescent offenders. Law and human behavior. 2004;28(5):483. doi: 10.1023/b:lahu.0000046430.65485.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AV, Hall EV, Perry JL. Black and blue: Exploring racial bias and law enforcement in the killings of unarmed black male civilians. Am Psychol. 2016;71(3):175–186. doi: 10.1037/a0040109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Research Evidence and Clinical Implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985–997. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MO, Wise LA, Jipguep MC, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. Neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination: Evidence from the black women’s health study. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70(3):272. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Waterman PD, Kosheleva A, Chen JT, Carney DR, Smith KW, et al. Exposing racial discrimination: implicit & explicit measures–the My Body, My Story study of 1005 US-born black & white community health center members. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwate NO, Goodman MS. Racism at the intersections: Gender and socioeconomic differences in the experience of racism among African Americans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(5):397–408. doi: 10.1037/ort0000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Neville HA. Construction and initial validation of the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Black women. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):289–302. doi: 10.1037/cou0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Health: Scientific Advances, Ongoing Controversies, and Emerging Issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015 doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. Reviews the state of research on self-reported experiences of discrimination and health, emphasizing unresolved issues and future directions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Troxel WM, Kravitz HM, Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Hall MH. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and sleep in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women. Health Psychol. 2013;32(7):810–819. doi: 10.1037/a0029938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:501–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete CD, McDonald MM, Molina LE, Sidanius J. Prejudice at the nexus of race and gender: an outgroup male target hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(6):933–945. doi: 10.1037/a0017931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negy C, Schwartz S, Reig-Ferrer A. Violated expectations and acculturative stress among U.S. Hispanic immigrants. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2009;15(3):255–264. doi: 10.1037/a0015109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NPR. Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of African-Americans, January 26-April 9, 2017 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived Discrimination and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant EA, Goplen J, Kunstman JW. Selective responses to threat: The roles of race and gender in decisions to shoot. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:1274–1281. doi: 10.1177/0146167211408617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie-Vaughns V, Eibach R. Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5-6):377–391. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4. Presents the theory of intersectional invisibility, emphasizing individuals with multiple subordinate identities. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Jonassaint C. The effects of race-related stress on cortisol reactivity in the laboratory: implications of the Duke lacrosse scandal. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(1):105–110. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CB, Vines AI, Kaufman JS, James SA. Cross-Sectional Association between Perceived Discrimination and Hypertension in African-American Men and Women: The Pitt County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(5):624–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(5):1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: social rejection versus achievement stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(4):318–327. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CS. A New Look at the Black Middle Class: Research Trends and Challenges. Sociological Focus. 2015;48(3):191–207. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2015.1039439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2014. 1058. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Investigation of Chicago Police Department 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke ME, Vaccarino V, Dunbar SB, Pemu P, Gibbons GH, Quyyumi AA, et al. Socioeconomic status discrimination and C-reactive protein in African-American and White adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;82:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.04.009. An empirical investigation documenting intersectional associations among race, socioeconomic status (SES), SES discrimination and C-Reactive Protein (a marker of inflammation) among African-Americans and Whites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke ME, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA, Lewis TT. Socioeconomic status discrimination is associated with poor sleep in African-Americans, but not Whites. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Miles to Go Before We Sleep: Racial Inequities in Health. Journal of health and social behavior. 2012;53(3):279–295. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455804. A review of emprical research on racial disparities in health and the potential role of discrimination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]