Abstract

Previously, we determined that diallyl disulfide (DADS) from garlic oil can inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 pathogenic factors by inactivating the transcription of key genes from three quorum sensing (QS) systems (las, rhl, and pqs) based on the effects of DADS on growth, virulence factor production (elastase, pyocyanin, biofilm, and swarming motility), and RNA transcription (real-time q-PCR). To further investigate the mechanisms underlying the inhibition of the three P. aeruginosa QS systems by DADS, high-throughput RNA and proteome sequencing techniques were used to study differences in the transcriptional and proteome expression of P. aeruginosa PAO1 following treatment with DADS. The RNA-seq and proteomic data are available via NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database with accession number GSE118801 and ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD011144, respectively. The experimental results indicated that all key genes of the three QS systems (las, rhl, and pqs) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 as well as the virulence factors (including exoprotease LasA, elastase LasB, lectin LecA and LecB, pyocyanin biosynthesis, and biofilm formation) regulated by these three QS systems were inhibited. This is consistent with our previous studies on the physiology, biochemistry, and RNA expression of P. aeruginosa treated with DADS. Additionally, our results also indicated that bacterial motility, chemotaxis, and two-component systems were inhibited by DADS treatment. All these changes abolish the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to environmental stimuli and cause the cells to be in a state of passivation. Further research is needed to determine how QS systems regulate these functions. Our findings could potentially contribute to the treatment and control of P. aeruginosa infection, virulence, and pathogenicity.

Keywords: diallyl disulfide, DADS, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, quorum sensing, virulence factors

Introduction

The extensive use of antibiotics has accelerated the formation of super resistant and multiple drug-resistant strains; thus, the strategies for prevention and control of pathogenic microbes must be changed (Woolhouse and Farrar, 2014). Quorum sensing (QS) has recently been established as an effective strategy for the treatment of pathogenic microbes. Many important pathogens regulate virulence via QS, which is a bacterial cell-to-cell communication system utilizing small signal molecules (Turan et al., 2017; Defoirdt, 2018; Prajapat and Saini, 2018). QS plays an important role in biofilm formation, pathogenicity, and virulence of pathogenic bacteria (Adonizio et al., 2006; Han et al., 2011; Husain et al., 2013; Hill and Liz-Marzán, 2017; Padder et al., 2018). The virulence and pathogenicity of pathogenic bacteria can be inhibited by inhibiting their QS. However, pathogenic growth is not inhibited and in this way QS inhibitors do not seem to provide favorable selection pressure for resistant bacteria. Previous studies have shown that many medicinal and edible plants produce QS inhibitors (Kalia, 2013; Kon and Rai, 2013).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous, clinically significant, Gram-negative bacillus and an opportunistic human pathogen (Stover et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2018). P. aeruginosa infections are particularly difficult to eradicate because this pathogen is prone to acquire resistance to multiple antibiotics and it prefers to form antibiotic-resistant biofilms (Galloway et al., 2012; He et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). In recent years, a number of studies have reported that garlic extract contains P. aeruginosa QS inhibitors, including ajoene, a sulfur compound from garlic (Rasmussen et al., 2005; Bodini et al., 2009; Harjai et al., 2010; Jakobsen et al., 2012). In addition, garlic extract has been demonstrated to increase the fragility of P. aeruginosa biofilms and inhibit their formation (Bjarnsholt et al., 2005). Previously, we found that diallyl disulfide (DADS), an ingredient from garlic oil (Li et al., 2014), could decrease elastase and pyocyanin production, biofilm formation, and swarming motility in P. aeruginosa PAO1, but did not affect bacterial growth (Li et al., 2018). Real time q-PCR revealed that the related virulence genes were down-regulated by DADS. Moreover, DADS down-regulated several important genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA, and pqsR) of the las, rhl, and pqs QS systems. Therefore, we concluded that DADS inhibits P. aeruginosa PAO1 pathogenic factors by inactivating the key genes of las, rhl, and pqs QS systems (Li et al., 2018).

In this study, to further investigate the mode of action of DADS in P. aeruginosa PAO1, we analyzed differences in transcriptome and proteome expression between untreated and DADS-treated P. aeruginosa PAO1 using high-throughput sequencing technology. Our research results may have important potential implications for the treatment of P. aeruginosa infection and for controlling its virulence and pathogenicity.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Reagents, Microorganisms, Media, and Cultivation

Strain P. aeruginosa PAO1, the DADS reagent, and Luria-Bertani (LB) medium were the same as in our previous study (Li et al., 2018). All solvents and reagents were of analytical grade unless otherwise specified.

Effects of DADS on P. aeruginosa PAO1 Transcriptome Based on RNA High-Throughput Sequencing

Luria-Bertani medium (50 mL) was inoculated with exponential growth phase P. aeruginosa PAO1 at a concentration of 108 CFU/mL. DADS was then added at a concentration of either 0 (control) or 0.64 mg/mL, in triplicate. All six experiment groups were incubated in a water bath shaker at 37°C with a shaking rate of 180 rpm for 5 h. Cells were then sampled and centrifuged from the three control groups and three DADS treatment groups. The cell precipitates in the control and DADS-treated groups were separately snap-frozen at -80°C.

RNA Sample Preparation

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc., United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA purity was determined using a NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, United States). All RNA samples had an A260:A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. RNA concentration was measured using a Qubit RNA Assay Kit with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, United States). RNA integrity was evaluated using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, United States); all samples had RNA integrity > 7.0.

Library Preparation for Strand-Specific Transcriptome Sequencing

RNA sequencing was accomplished by Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). A total of 3 μg RNA per sample was used as input material for RNA sample preparation. Sequencing libraries were generated using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. The rRNA was removed using a specialized kit that leaves the mRNA. Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5×). First strand cDNA was synthesized using a random hexamer primer and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNaseH). Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA polymerase I and RNase H. PCR was then performed with Phusion High-fidelity DNA polymerase, universal PCR primers, and Index primers. Finally, products were purified (AMPure XP system) and library quality was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. RNA sequencing was performed at Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) on an Illumina Hiseq platform.

Reads Mapping to the Reference Genome, Novel Gene and Gene Structure Analysis, and Quantification of Gene Expression Levels

The reference genome and gene model annotation files were directly downloaded from the genome website of NCBI1. Both reference genome index building and aligning of the clean reads to the reference genome were performed using bowtie2-2.2.3 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Rockhopper was used to identify novel genes, operons, and transcription start sites. This system can be used for efficient and accurate analysis of bacterial RNA-seq data, thus assisting with the interpretation of bacterial transcriptomes (McClure et al., 2013). Next, the sequences 700 bp upstream of the transcription start sites were extracted for promoter prediction using Time-Delay Neural Network (TDNN). HTSeq v0.6.1 was used to count the number of reads that mapped to each gene, and the Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads (FPKM) for each gene was then calculated based on the length of the gene and the reads counts that mapped to the gene (Langmead et al., 2009).

Differential Expression Analysis and GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

Differential expression analysis of the two groups was performed using the DESeq R package (1.18.0). The resulting P-values were adjusted using Benjamini and Hochberg’s method for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 identified by DESeq were assigned as differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes was implemented using the GOSeq R package, which corrects for gene length bias. GO terms with corrected P-value < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched by differentially expressed genes. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database is a resource for deciphering the functions and abilities of various biological systems based on molecular-level information, especially large-scale molecular datasets generated by high-throughput experimental technologies including genome sequencing2. KOBAS software was used to test the statistical enrichment of differentially expressed genes in KEGG pathways (Mao et al., 2005).

Accession Number

The RNA-seq datasets are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE118801.

Effects of DADS on the Proteome of P. aeruginosa PAO1 by iTRAQ High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis

To establish the effect of DADS on the P. aeruginosa proteome, 50-mL LB medium samples were inoculated at 108 CFU/mL with exponential growth phase P. aeruginosa PAO1. DADS was then added at a concentration of 0 (control) or 0.64 mg/mL, in triplicate. The six experimental groups were incubated for 5 h in a water bath shaker at 37°C with a shaking rate of 180 rpm. Cells from the three control groups and three DADS treatment groups were then sampled and centrifuged. The cell precipitate from each experiment group was snap-frozen at -80°C.

Sample Preparation and iTRAQ Labeling

Protein extracts were cleaned up using the RIPA reagent. Protein concentration was estimated by Bradford assay using BSA as the standard (BCA Assay Kit, Biotech) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Protein iTRAQ sequencing analysis was performed at Guangzhou FitGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Proteins were digested according to the FASP method (Wisniewski et al., 2009; Lan et al., 2012; Kambiranda et al., 2014). iTRAQ labeling was performed using the iTRAQ reagents – 8plex Kit (Applied Biosystems, SCIEX) according to the user’s manual. The three control P. aeruginosa PAO1 samples were labeled with iTRAQ tags 114, 115, and 116, while the three P. aeruginosa PAO1 samples treated with DADS were labeled with iTRAQ tags 117, 118, and 119.

High-pH Reversed-Phase Chromatography

iTRAQ labeled samples were diluted to 100 μL with 20 mM HCOONH4 and 2 M NaOH (pH 10) prior to HPLC. Peptides were separated by a linear gradient consisting of 20 mM HCOONH4, 2 M NaOH, and 80% CAN, from 5 to 40% of mobile phase B for 30 min at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The UV detector was set at 214/280 nm, and fractions were collected every 1 min. In total, 10 fractions were pooled for each sample and dried using a vacuum centrifuge.

RPLC-MS Analysis

Peptides were acidified with 50% CF3COOH, and then separated by a linear gradient from 5 to 40% of mobile phase B for 70 min at a flow rate of 300 mL/min. MS analysis was performed on a TripleTOF 5600 system (AB SCIEX) in information dependent mode. MS spectra were acquired across the mass range of 400–1250 m/z in high resolution mode using 250 ms accumulation time per spectrum. A maximum of 50 precursors per cycle was chosen for fragmentation from each MS spectrum with 100 ms minimum accumulation time for each precursor and dynamic exclusion for 20 s. Tandem mass spectra were recorded in high sensitivity mode with rolling collision energy on and iTRAQ reagent collision energy adjustment on.

Data Analysis

Relative quantification and protein identification were performed with ProteinPilot software (version 4.0, revision 148085, Applied Biosystems) using the Paragon algorithm as the search engine. Specified processing included quantitate, bias correction, and background correction. All proteins identified had ≥95% confidence, and the protein confidence threshold cutoff was set to 1.3 (unused) with at least more than one peptide above the 95% confidence level. To designate significant changes in protein expression, fold-changes > 2 or < 0.5 were set as cutoff values. The differentially expressed proteins were examined using QuickGO (3Annotation Blacklist4) for GO annotation and enrichment analyses. The GO project classifies proteins in three categories based on their annotation: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Following annotation, the enzyme codes assigned to each protein were sequentially mapped to the known metabolic pathways in KEGG2 for biological pathway analysis.

Accession Number

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD011144.

Results

The Effects of DADS on P. aeruginosa PAO1 Transcription

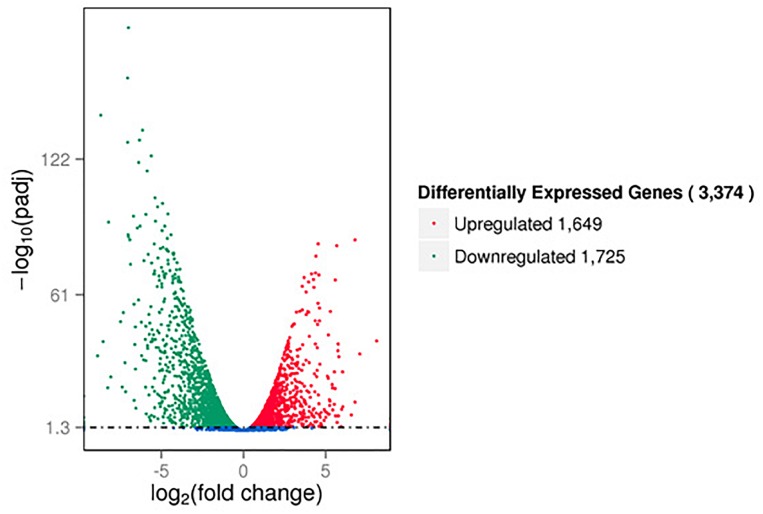

The RNA-seq results showed that a large number of P. aeruginosa PAO1 genes were differentially expressed following DADS treatment. We found that more than 50% of all detected genes (3374 of 5630 genes) were more than twofold differentially expressed following DADS treatment (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). The volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (Figure 1) showed that the differentially expressed genes were either more than twofold downregulated (green dots, 1,725 genes) (Supplementary Table S4) or upregulated (red dots, 1,649 genes) (Supplementary Table S5).

FIGURE 1.

Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes based on RNA sequencing analysis of untreated and DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Each gene is represented by a dot in the graph. The x-axis and y-axis represent the log2 value of the fold change and the t-statistic as –log10 of the p-value, respectively. The genes represented in red (upregulated) and green (downregulated) are differentially expressed genes with >twofold change and a p-value < 0.05.

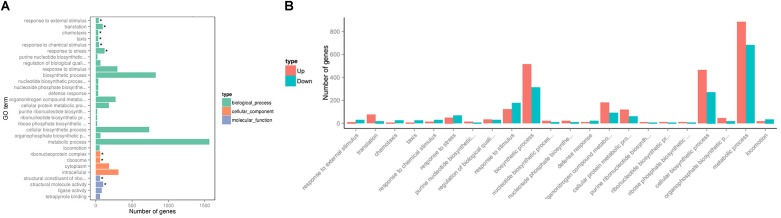

To investigate changes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 gene expression patterns following DADS treatment, the percentage of genes in each GO category was analyzed. The GO categories significantly enriched (q < 0.05) among the differentially expressed genes are shown in Figure 2. Within the biological process category, 22 terms were enriched in the differentially expressed genes, while only four terms were enriched in the cellular component category and the molecular function category, respectively (Figure 2A). In the biological process category, “response to external stimulus,” “translation,” “chemotaxis,” “taxis,” “response to chemical stimulus,” and “response to stress” were the most significantly enriched terms. The terms “response to stimulus,” “chemotaxis,” “taxis,” “response to chemical stimulus,” “response to stress,” “response to external stimulus,” and “locomotion” contained more downregulated than upregulated genes, whereas upregulated genes were more prevalent than downregulated genes in the other significantly enriched terms (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Significantly enriched Gene Ontology categories (q-value < 0.05) of differentially expressed genes based on RNA sequencing analysis of the DADS-treated group compared to the control group. Three main categories were identified: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. (A) the most highly enriched GO terms; (B) the most highly enriched GO terms in the biological process category.

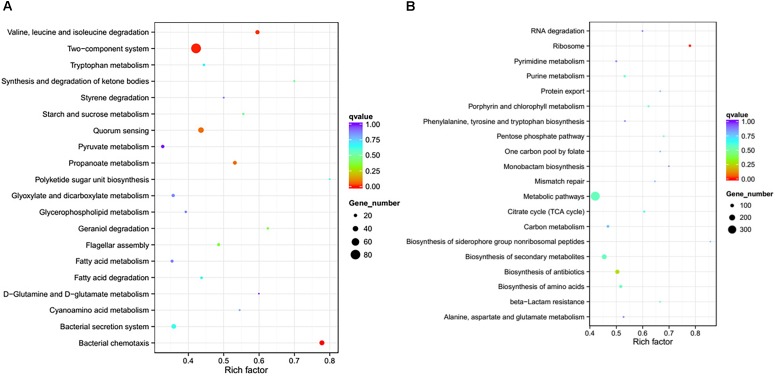

To further investigate the biological functions of the differentially expressed genes, KEGG analysis was performed to classify the functions of the identified genes (Figure 3). The downregulated genes were significantly enriched in the following KEGG pathway terms (Figure 3A): Bacterial chemotaxis, Two-component system, Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, Propanoate metabolism, QS, Flagellar assembly, Geraniol degradation, Synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, Starch and sucrose metabolism, and Bacterial secretion system. The upregulated genes were significantly enriched in the following KEGG pathway terms (Figure 3B): Ribosome, Biosynthesis of antibiotics, Biosynthesis of amino acids, Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, beta-Lactam resistance, Pentose phosphate pathway, Metabolic pathways, Purine metabolism, and Citrate cycle (TCA cycle).

FIGURE 3.

Significantly enriched KEGG pathway scatter plot (0.00 < q-value < 1.00) of differentially expressed genes based on RNA sequencing analysis of the DADS-treated group compared to the control group. (A) downregulated genes; (B) upregulated genes.

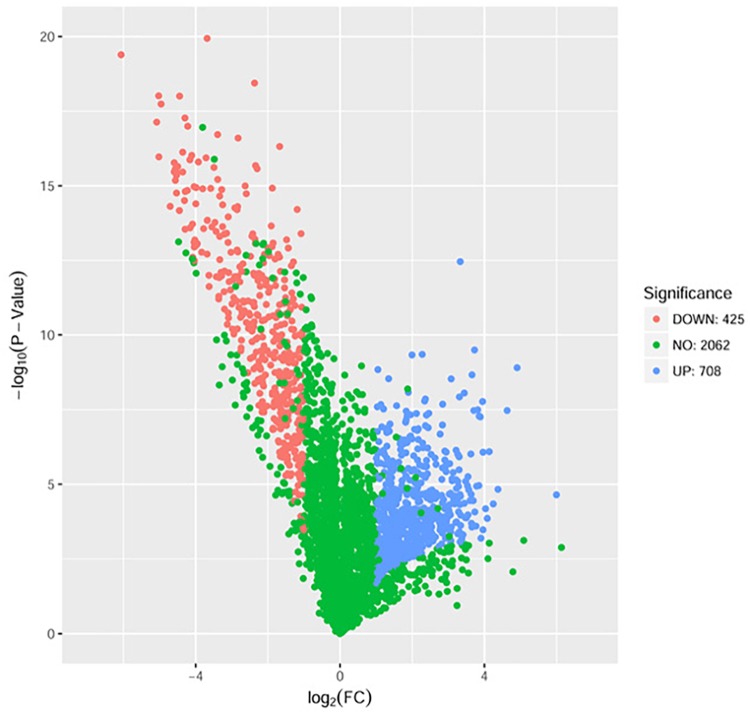

The Effects of DADS on P. aeruginosa PAO1 Proteome

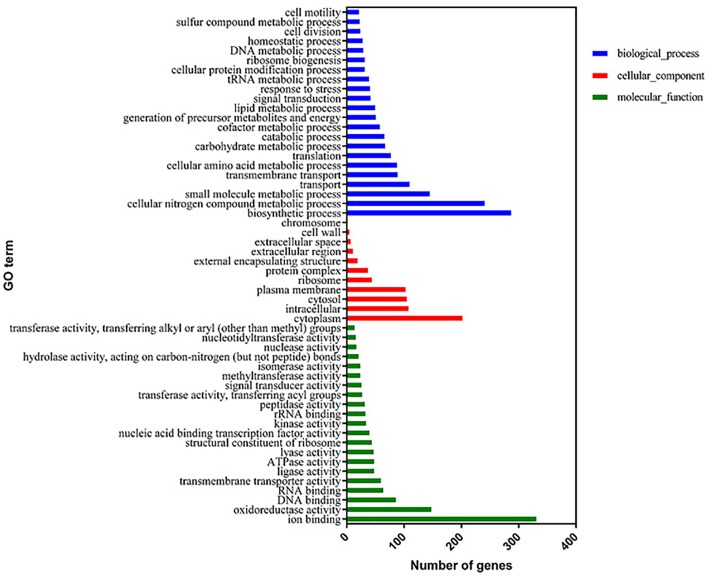

The proteome sequencing results revealed that more than 30% of all detected proteins (1133 of 3304 proteins) were more than twofold differentially expressed following DADS treatment (Supplementary Tables S6, S7). The volcano plots of differentially expressed proteins (Figure 4) showed that 425 proteins were down-regulated (red dots) and 708 proteins were up-regulated (blue dots) > twofold following DADS treatment (Supplementary Tables S6, S7). The GO categories significantly enriched (q < 0.05) among those differentially expressed genes are shown in Figure 5. Within the biological process category, 22 terms were enriched in differentially expressed genes, while 11 and 21 terms were enriched in the cellular component category and the molecular function category, respectively. Most of the terms in the biological process category were related to metabolism. Of these, the terms “response to stress,” “cell motility” and “signal transduction” were consistent with the GO analysis of the RNA high-throughput sequencing. The term “sulfur compound metabolic process” is significant for understanding the mechanism of DADS in P. aeruginosa PAO1.

FIGURE 4.

Volcano plots of the differentially expressed genes based on proteome sequencing analysis of untreated and DADS-treated P. aeruginosa PAO1. Each protein is represented by a dot in the graph. The x-axis and y-axis represent the log2 value of fold change and the t-statistic as –log10 of p-value, respectively. The genes represented in blue (up regulated) and red (down regulated) are differentially expressed genes with >twofold change and a p-value < 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

Significantly enriched Gene Ontology categories (q-value < 0.05) of differentially expressed genes based on proteome sequencing analysis of the DADS-treated group compared to the control group. Three main categories were identified: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function.

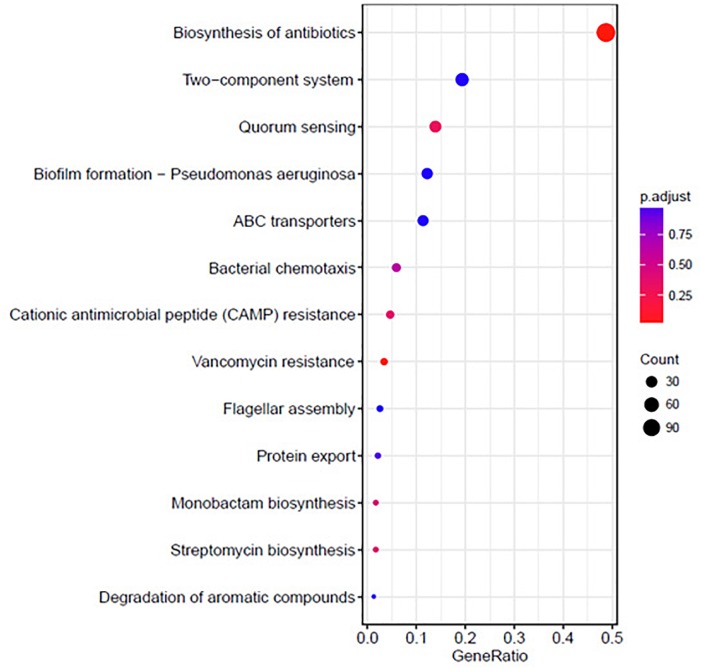

The KEGG analysis results are shown in Figure 6. The differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in the following KEGG pathway terms: Biosynthesis of antibiotics, Two-component system, QS, Biofilm formation, ABC transporters, Bacterial chemotaxis, Cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) resistance, Vancomycin resistance, Flagellar assembly, and Protein export.

FIGURE 6.

Significantly enriched KEGG pathway scatter plot (0.00 < q-value < 1.00) of differentially expressed genes based on proteome sequencing analysis of the DADS-treated group compared to the control group.

Discussion

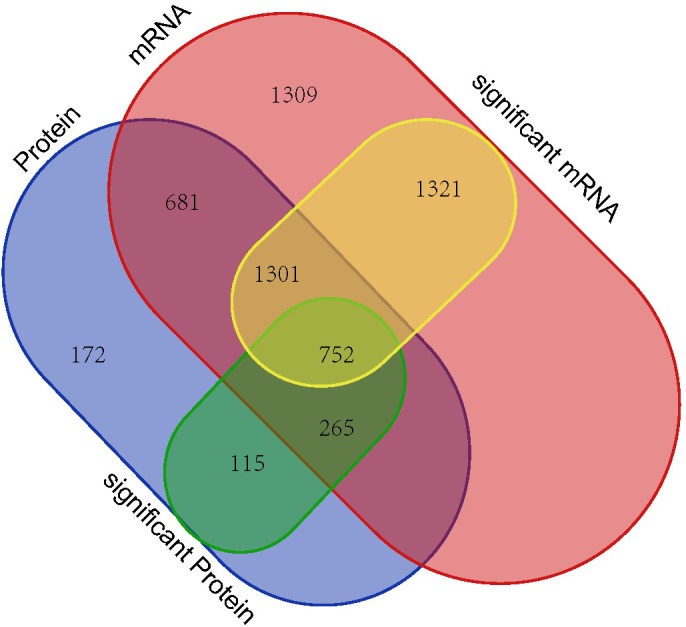

The RNA and proteome high-throughput sequencing results showed that > 3,000 genes (1,725 down-regulated and 1,649 up-regulated genes) and 1133 proteins (425 down-regulated and 708 up-regulated proteins) were differentially expressed in P. aeruginosa PAO1 following DADS treatment, respectively. These results indicate that DADS treatment has an immense influence on P. aeruginosa PAO1 gene expression. Comparison of the iTRAQ and RNA-seq data revealed that the number of differentially expressed genes of the RNA-seq data was 2.97 times higher than that of the iTRAQ data (Supplementary Tables S2, S7). This suggested that RNA-seq is more sensitive at detecting gene expression than iTRAQ. RNA sequencing can identify more expressed genes than proteomic analysis. When integrating these datasets, we identified 752 genes with significant differences following DADS treatment at both the mRNA and protein levels as shown in Venn diagram (Figure 7). The Venn diagram in Figure 7 shows the differentially expressed genes are highly consistent in RNA-seq and proteomic analysis, though it has been widely reported that the correspondence of transcriptomic and proteomic data is low due to the numerous and complex regulatory mechanism in gene transcription and protein synthesis (Dressaire et al., 2010; Haider and Pal, 2013; Margalef-Català et al., 2016).

FIGURE 7.

Venn diagram showing all identified, as well as all significantly enriched, mRNAs and proteins and their overlaps.

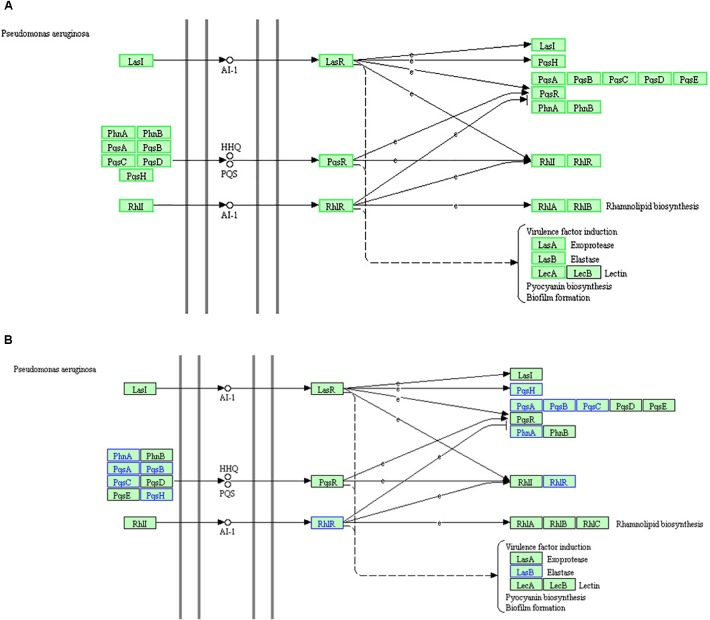

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and GO analyses of the proteome and RNA high-throughput sequencing results were consistent. Based on these data, the “QS” pathway in P. aeruginosa is the most significant KEGG pathway among the enriched downregulated genes. However, the KEGG “QS” pathway, is not enriched in the corresponding GO term because this term is not listed in the GO database. The KEGG “QS” pathway in RNA high-throughput sequencing analysis (A) and proteome high-throughput sequencing analysis (B) is shown in Figure 8. There are three different QS systems in P. aeruginosa, las, rhl, and pqs (Whiteley et al., 1999; Waters and Bassler, 2005; Wilder et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2014), which are hierarchically arranged; the las system positively regulates both the rhl and pqs systems, and the rhl and pqs systems regulate each other (Figure 8). In the las system (Passador et al., 1993; Finch et al., 1998), LasI catalyzes the synthesis of the signal molecule (AI-1), which binds LasR and activates the expression of several target genes, including lasI (suggesting that the las system positively regulates itself); pqsH, pqsA, pqsB, pqsC, pqsD, pqsE, pqsR, phnA, and phnB (suggesting that the las system positively regulates the pqs system); and rhlI and rhlR (suggesting that the las system positively regulates the rhl system). In the pqs system (Williams and Cámara, 2009), PhnA, PhnB, PqsA, PqsB, PqsC, PqsD, and PqsH are combined to catalyze the synthesis of the signal molecules (HHQ or PQS), which bind PqsR and activate the expression of several genes, including pqsR (suggesting that the pqs system positively regulates itself), rhlI, and rhlR (suggesting that the pqs system positively regulates the rhl system). In the rhl system (Pearson et al., 1995; Latifi et al., 1996), RhlI catalyzes the synthesis of the signal molecule (AI-1), which binds RhlR and activates the expression of several genes, including pqsR, phnA, and phnB (suggesting that the rhl system positively regulates the pqs system); rhlI and rhlR (suggesting that the rhl system positively regulates itself); and rhlA and rhlB (suggesting that the rhl system positively regulates rhamnolipid biosynthesis). Furthermore, Figure 8A also shows that the virulence factors LasA (exoprotease) and LasB (elastase), LecA and LecB (lectin), pyocyanin biosynthesis, and biofilm formation are co regulated by the las, pqs, and rhl systems.

FIGURE 8.

The KEGG “quorum sensing” pathway based on RNA high-throughput sequencing analysis (A) and proteome high-throughput sequencing analysis (B). (A) The green box proteins indicate that the RNA expression of the gene is down regulated, while the black box proteins show no changes in RNA expression. (B) Proteins in blue indicate downregulated expression, while proteins in black indicate no change in expression.

RNA analysis of the “QS” pathway (Figure 8A) demonstrated that the key genes of the three QS systems were downregulated. Elastase production, pyocyanin biosynthesis, and biofilm formation were also downregulated. These results are consistent with the q-PCR results and physiological observations in our previous study (Li et al., 2018). DADS inhibits the expression of all key genes of the three hierarchical QS systems, and thus inhibits the production of virulence factors regulated by the QS systems.

Both the RNA and proteome high-throughput sequencing GO and KEGG analysis results showed that the downregulated genes were also significantly enriched in bacterial chemotaxis, bacteria motility, and two-component systems. GO analysis demonstrated that the response to stimulus (response to stimulus, response to stress, response to chemical stimulus, and response to external stimulus terms), chemotaxis (chemotaxis and taxis terms), and bacterial motility (locomotion term) related genes were most highly downregulated. Furthermore, KEGG analysis also showed that the downregulated genes were significantly enriched in the KEGG pathway terms “Bacterial chemotaxis,” “Flagellar assembly,” and “Two-component system.”

The downregulated genes were enriched in “bacterial chemotaxis” both in the GO terms and KEGG pathways. Bacterial chemotaxis is the movement of bacterial cells in response to chemical stimuli (Hazelbauer, 2012; Parkinson, 2013). For example, bacterial cells direct their movements according to certain chemicals in their environment. This is important for bacteria to find food or to flee from toxins by swimming motility toward or away from certain chemical molecules. Therefore, bacterial chemotaxis depends on bacterial motility and they are closely related. The KEGG pathway term “Flagellar assembly” is closely related to GO term “bacterial motility.” The downregulated genes were enriched in the “flagellar assembly” KEGG pathway and “bacterial motility” GO term. This indicates that bacterial motility was inhibited following DADS treatment. These results were consistent with our previous study (Li et al., 2018) demonstrating that DADS inhibited the swarming motility of P. aeruginosa PAO1 based on physiological observations. The “two-component system” KEGG pathway is also known as “two-component signal transduction system,” which enables bacteria to sense, respond, and adapt to environmental or intracellular changes (Stock et al., 2000; Mascher et al., 2006; Capra and Laub, 2012). Two-component systems are responsible for environmental information processing and signal transduction. Therefore, the enriched GO term “response to stimulus” was consistent with the “two-component system” KEGG pathway. Following DADS treatment, P. aeruginosa PAO1 was no longer sensitive to environmental changes and stimulation. The enrichment of downregulated genes in the terms “bacterial chemotaxis,” “two-component system,” and “bacterial motility,” suggests that P. aeruginosa PAO1 cells were in a “passivation” state following DADS treatment.

Additionally, the enriched GO term “sulfur compound metabolic process” in the proteome high-throughput sequencing analysis was significant for understanding the mechanism of action of DADS in P. aeruginosa PAO1. These experimental results provide directions for further studies.

In summary, based on RNA and proteome high-throughput sequencing analysis, following DADS treatment, all key genes of the three QS systems (las, rhl, and pqs) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 were inhibited and thus the virulence factors (including exoprotease LasA, elastase LasB, pyocyanin biosynthesis, and biofilm formation) regulated by these three QS systems were also inhibited. The QS systems of P. aeruginosa PAO1 constituted the most significant pathway inhibited by DADS treatment. Additionally, bacterial motility, chemotaxis, and two-component systems were also inhibited by DADS treatment. All these changes reduce the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to environmental stimuli and cause the cells to enter a passivation state. Further research is needed to determine whether and how bacterial motility, chemotaxis, and two component systems are regulated by the QS systems.

Author Contributions

W-RL conceived and supervised the study and wrote the paper. W-RL, Y-KM, and XW performed all the experiments. W-RL and Y-KM carried out the data analyses. X-BX, Q-SS, T-LS, and HP contributed reagents or materials.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Professor Zhang Lixin and Dai Huanqin from the CAS Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, Beijing, China, for the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains.

Funding. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31500113), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2016A030313800), the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Research Project (No. 201607020020), and the Guangdong Academy of Sciences project (2017GDASCX-0102).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03222/full#supplementary-material

Gene description of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Differentially expressed gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Differential analysis results of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

The downregulated gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

The upregulated gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Protein data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on proteome sequencing analysis.

The twofold differentially expressed protein data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on proteome sequencing analysis.

References

- Adonizio A. L., Downum K., Bennett B. C., Mathee K. (2006). Anti-quorum sensing activity of medicinal plants in southern Florida. J. Ethnopharmacol. 105 427–435. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnsholt T., Jensen P. Ø, Rasmussen T. B., Christophersen L., Calum H., Hentzer M. (2005). Garlic blocks quorum sensing and promotes rapid clearing of pulmonary Pseudomonas aerginuosa infections. Microbiology 151 3873–3880. 10.1099/mic.0.27955-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodini S. F., Manfredini S., Epp M., Valentini S., Santori F. (2009). Quorum sensing inhibition activity of garlic extract and p-coumaric acid. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 49 551–555. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capra E. J., Laub M. T. (2012). Evolution of two-component signal transduction systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66 325–347. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T. (2018). Quorum-sensing systems as targets for antivirulence therapy. Trends Microbiol. 26 313–328. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressaire C., Laurent B., Loubière P., Besse P., Cocaign-Bousquet M. (2010). Linear covariance models to examine the determinats of protein levels in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Biosyst. 6 1255–1264. 10.1039/c001702g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch R. G., Pritchard D. I., Bycroft B. W., Williams P., Stewart G. S. (1998). Quorum sensing: a novel target for anti-infective therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42 569–571. 10.1093/jac/42.5.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway W. R. J. D., Hodgkinson J. T., Bowden S., Welch M., Spring D. R. (2012). Applications of small molecule activators and inhibitors of quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 20 449–458. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Kong W. N., Jin S., Chen L., Xu Y. Y., Duan K. M. (2014). PqsR-dependent and PqsR-independent regulation of motility and biofilm formation by PQS in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Basic Microbiol. 54 633–643. 10.1002/jobm.201300091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider S., Pal R. (2013). Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data. Curr. Genomics 14 91–110. 10.2174/1389202911314020003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T. L., Cannon R. D., Villas-Boas S. G. (2011). The metabolic basis of Candida albicans morphogenesis and quorum sensing. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48 747–763. 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harjai K., Kumar R., Singh S. (2010). Garlic blocks quorum sensing and attenuates the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58 161–168. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00614.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelbauer G. L. (2012). Bacterial chemotaxis: the early years of molecular studies. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66 285–303. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. C., Jia X. J., Yang S. S., Xu X. Y., Sun K. L., Li C. Y., et al. (2018). Heteroresistance to carbapenems in invasive Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51 413–421. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E. H., Liz-Marzán L. M. (2017). Toward plasmonic monitoring of surface effects on bacterial quorum-sensing. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface 32 1–10. 10.1016/j.cocis.2017.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husain F. M., Ahmad I., Asif M., Tahseen Q. (2013). Influence of clove oil on certain quorum-sensing-regulated functions and biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Biosci. 38 835–844. 10.1007/s12038-013-9385-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen T. H., Gennip M. V., Phipps R. K., Shanmugham M. S., Christensen L. D., Alhede M., et al. (2012). Ajoene, a sulfer-rich molecule from garlic inhibits genes controlled by quorum sensing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 2314–2325. 10.1128/AAC.05919-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V. C. (2013). Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 31 224–245. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambiranda D., Katam R., Basha S. M., Siebert S. (2014). iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics of developing and ripening muscadine grape berry. J. Proteome Res. 13 555–569. 10.1021/pr400731p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K. V., Rai M. K. (2013). Combining essential oils with antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents to overcome multidrug-resistant bacteria. Fight. Multidrug Resist. Herb. Extracts Essent. Oils Compon. 10 149–164. 10.1016/B978-0-12-398539-2.00010-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P., Li W., Schmidt W. (2012). Complementary proteome and transcriptome profiling in phosphate-deficient Arabidopsis roots reveals multiple levels of gene regulation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11 1156–1166. 10.1074/mcp.M112.020461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L. (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latifi A., Foglino M., Tanaka K., Williams P., Lazdunski A. (1996). A hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhlR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol. Microbiol. 21 1137–1146. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. J., Jo A. R., Jang M. C., Nam J., Choi H. J., Choi G. W., et al. (2018). Analysis of two quorum sensing-deficient isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 119 162–169. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. R., Ma Y. K., Shi Q. S., Xie X. B., Sun T. L., Peng H., et al. (2018). Diallyl disulfide from garlic oil inhibits virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by inactivating key quorum sensing genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102 7555–7564. 10.1007/s00253-018-9175-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. R., Shi Q. S., Liang Q., Huang X. M., Chen Y. B. (2014). Antifungal effect and mechanism of garlic oil on Penicillium funiculosum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98 8337–8346. 10.1007/s00253-014-5919-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Cai T., Olyarchuk J. G., Wei L. (2005). Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21 3787–3793. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalef-Català M., Araque I., Bordons A., Reguant C., Bautista-Gallego J. (2016). Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of Oenococcus oeni adaptation to wine stress conditions. Front. Microbiol. 7:1554 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T., Helmann J. D., Unden G. (2006). Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70 910–938. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure R., Balasubramanian D., Sun Y., Bobrovskyy M., Sumby P., Genco C. A., et al. (2013). Computational analysis of bacterial RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 e140. 10.1093/nar/gkt444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padder S. A., Prasad R., Shah A. H. (2018). Quorum sensing: a less known mode of communication among fungi. Microbiol. Res. 210 51–58. 10.1016/j.micres.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J. S. (2013). “Bacterial chemotaxis,” in Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics, 2nd Edn, eds Brenner S., Miller J. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ),258–261. [Google Scholar]

- Passador L., Cook J. M., Gambello M. J., Rust L., Lglewski B. H. (1993). Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science 260 1127–1130. 10.1126/science.8493556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. P., Passador L., Lglewski B. H., Greenberg E. P. (1995). A second N-acylhomoserine lactone signal produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 1490–1494. 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapat M. K., Saini S. (2018). Logic of two antagonizing intra-species quorum sensing systems in bacteria. Biosystems 165 88–98. 10.1016/j.biosystems.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T. B., Bjarnsholt T., Skindersoe M. E., Hentzer M., Kristoffersen P., Köte M., et al. (2005). Screening for quorum-sensing inhibitors (QSI) by use of a novel genetic system, the QSI selector. J. Bacteriol. 187 1799–1814. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1799-1814.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. (2000). Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69 183–215. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C. K., Pham X. Q., Erwin A. L., Mizoguchi S. D., Warrener P., Hickey M. J., et al. (2000). Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406 959–964. 10.1038/35023079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan N. B., Chormey D. S., Büyükplnar C., Engin G. O., Bakirdere S. (2017). Quorum sensing: little talks for an effective bacterial coordination. TrAC-Trend. Anal. Chem. 91 1–11. 10.1016/j.trac.2017.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waters C. M., Bassler B. L. (2005). Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21 319–346. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley M., Lee K. M., Greenberg E. P. (1999). Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 13904–13909. 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder C. N., Diggle S. P., Schuster M. (2011). Cooperation and cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the roles of the las, rhl and pqs quorum-sensing systems. ISME J. 5 1332–1343. 10.1038/ismej.2011.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P., Cámara M. (2009). Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12 182–191. 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski J. R., Zougman A., Nagaraj N., Mann M. (2009). Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6 359–362. 10.1038/nmeth.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse M., Farrar J. (2014). Policy: an intergovernmental panel on antimicrobial resistance. Nature 509 555–557. 10.1038/509555a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gene description of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Differentially expressed gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Differential analysis results of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

The downregulated gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

The upregulated gene data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on RNA-seq analysis.

Protein data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on proteome sequencing analysis.

The twofold differentially expressed protein data of DADS-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 vs. control groups based on proteome sequencing analysis.