Abstract

Buddhist philosophy is a way of life that transcends the borders of religion and focuses on the alleviation of suffering. The core teaching of Buddha was the Four Noble Truths: there is suffering, suffering is caused by clinging and ignorance, there is a way out of suffering and that way is the Noble Eightfold Path. The medical analogy in diabetes care would include identification of diabetes, understanding its etiopathogenesis, and how prognosis can be improved with appropriate care and management of this chronic disorder. Gaining awareness about the cause of illness and conducting our lives in a manner that nourishes and maintains long-term good health leads to improved outcomes for individuals living with diabetes and improve their overall well-being. The Noble Eightfold Path in Buddhism constitutes of right view, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. These elements of the Eightfold Path can be taken as guiding principles in diabetes care. Buddhist meditation techniques, including mindfulness meditation-based strategies, have been used for stress reduction and management of chronic disorders such as chronic pain, depression, anxiety, hypertension, and diabetes. In this article, we focus on how Buddhist philosophy offers several suggestions, precepts, and practices that guide a diabetic individual toward holistic health.

Keywords: Buddhism, diabetes care, four noble truths, liberating insight, meditation, metabolic karma, mindfulness meditation, mindfulness-based stress reduction dharma, Noble Eightfold Path, suffering

BUDDHISM

The origin of Buddhism goes back to between 6th and 4th century BC in the eastern part of Ancient India. The religion is largely based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, the prince of the Shakya clan who became an ascetic and discovered the Middle Path or the Buddha Dharma, while meditating under a peepal (Ficus religiosa or the sacred fig) tree in Bodh Gaya.[1] He came to be known as Buddha, Samyaksambuddha, or The Enlightened One. In a broad sense, the Middle Path is a path of moderation away from extremes of self-indulgence or self-mortification. With his first sermon at Sarnath, the Buddha is believed to have set in motion the Wheel of Dharma Chakra and the first Sangha, monastic community of ordained monks or nuns, was formed.

King Ashoka of the Maurya Empire was instrumental in the early spread of the religion, and it is noteworthy that he established free hospitals, provided free education, and was a champion of equality and human rights. As a religious philosophy, Buddhism preached a way out of suffering in a simple and direct manner that found favor with the common man. The concept of social equality and the formation of Sangha (Buddhist monastic order) further strengthened the spread of Buddhism.[2] Over time, the religion spread from the Gangetic plains of Northeastern India to large parts of Central, East, and Southeast Asia and saw the emergence of several movements and schools of Buddhist philosophy – Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana and Zen being the most practiced schools of thought among these.[2] In recent times, there has been a growing worldwide interest in Buddhism and it has been one of the fastest growing religious philosophies in the West. As per recent estimates, the religion is practiced by 535 million people, constituting 7%–8% of the world population.[3]

DIABETES AMONG BUDDHIST POPULATIONS

The diabetes epidemic has spread worldwide with no respect to ethnicity, race, or religion. Several studies have reported a high prevalence of diabetes among Buddhist monks, which is believed to be related to dietary habits (prolonged fasting with subsequent intake of high carbohydrate, high fat, low fiber, and protein deficient food) coupled with a sedentary lifestyle.[4,5,6] Challenges in diabetes self-management have been reported among Buddhist people in recent studies.[7] On the other hand, stronger Buddhist values have been associated with better diabetes self-care including diet, medications, and doctor visits and better glycemic control in some populations.[8]

BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY

“Liberating insight” is an essential principle of the Buddhist philosophy and comprises:

Dependent Origination: The mind creates suffering

-

The Four Noble Truths:

- Suffering (Dukkha) is an ingrained part of existence

- The origin of suffering is craving and ignorance

- Cessation of this craving is the way out of suffering

- This can be achieved by following the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold Path includes right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

Buddhism transcends the borders of religion – it is a philosophy and a way of life with a focus on overcoming suffering which can be caused by several factors including chronic metabolic disorders such as diabetes.

“While pain is inevitable, suffering is optional.”

This simple insight from Buddhist philosophy informs modern semantics in diabetology – we use the phrase “living with diabetes” and not “suffering from diabetes.” An understanding of Buddhist principles can help all diabetes practitioners, educators, patients, and their families achieve greater success in overcoming this challenging disease.

THE THREE JEWELS: BUDDHA, DHARMA, AND SANGHA

A Buddhist takes refuge in the Three Jewels: The Buddha (the one with true knowledge), the Dharma (the Four Noble Truths and The Eightfold Path), and the Sangha (the community).

Buddhaṃ śaraṇaṃ gacchāmi.

Dharmaṃ śaraṇaṃ gacchāmi.

Saṃghaṃ śaraṇaṃ gacchāmi.

I take refuge in the Buddha.

I take refuge in the Dharma.

I take refuge in the Sangha.

Likewise, a person with diabetes should be encouraged to take refuge in true knowledge (avoiding myths and misconceptions, seeking guidance), the middle path (lifestyle modification and management), and the community (a supportive family, health-care team, and society). The “Sangha” also delineates our “collective responsibility”– which in the context of diabetes care should include the family, the health-care team, and community and government bodies as well.

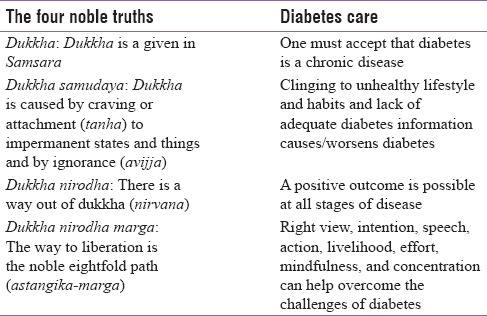

THE FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS IN DIABETES CARE

While the understanding of the Four Noble Truths can help individuals and communities overcome every challenge in life, diabetes is no exception. Acceptance of disease, identification of our nature to cling to unhealthy habits, a clear understanding that challenges can be overcome and the way to do so is by following the Noble Path: These are the Four Truths of Diabetes Care which can assist patients and their families to live happily with diabetes. The First Noble Truth identifies the disease, second provides etiology, third gives a prognosis, and fourth suggests a remedy.[9] Table 1 lays out this concept.

Table 1.

The Four Noble Truths of diabetes care

THE MIDDLE WAY - THE NOBLE EIGHTFOLD PATH AND DIABETES

The Buddha delineated a path of moderation in his first sermon – the middle way (Madhyam-pratipad) between extremes of asceticism, on one hand, to indulgence in hedonistic pleasures on the other. This would apply to living with diabetes very aptly. A diagnosis of diabetes should not be met with negativity, and the individual should not perceive it as having to “give up” everything in life. Life with diabetes does not mean renunciation but making the right choices toward healthy living.

The Noble Eightfold Path (Astangika marga) is the core teaching of Buddhism and was described by Buddha as the Middle Way of moderation. It consists of eight interconnected practices related to self-restraint, discipline, mindfulness, and meditation, that when developed together, lead to cessation of Dukkha. This octet is depicted by the Wheel of D. Chakra [Figure 1], the eight spokes of the wheel symbolizing the eight elements of the path.

Figure 1.

The Wheel of Dharma

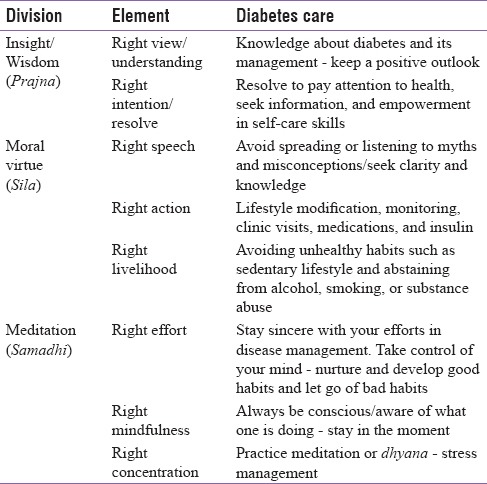

The eightfold path has been compared to cognitive psychology, wherein right view factor can be interpreted as how one's mind views the world, and how that leads to patterns of thought, intention, and actions which form the remaining elements of the path.[9,10] The elements of this path have previously been described as corollaries of illness-prevention and health behavior.[11] This can be applicable to diabetes and other chronic cardiometabolic conditions as well. Table 2 illustrates the same.

Table 2.

The Noble Eightfold Path

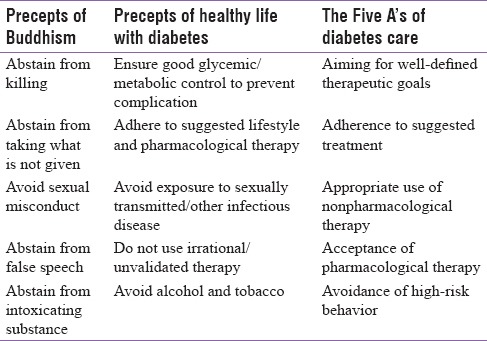

Sila/Panch-Sila - Moral virtues or the five ethical precepts

The second group of the Noble Path consists of moral virtues including right speech, action, and livelihood. These have been laid out as certain moral behavioral guidelines known as the five ethical precepts for all Buddhism devotees. The same can be paraphrased to create five healthy behaviors, which help prevent diabetes-related complications [Table 3]. The model that we propose encourages acceptance of pharmacological therapy, appropriate use of nonpharmacological therapy, adherence to suggested treatment, aiming for well-defined therapeutic goals, and avoidance of high-risk behavior (The 5 As).

Table 3.

The five ethical precepts (Panch-sila) in relation to diabetes care

SAMADHI/MEDITATION AND HEALTH

A great emphasis is placed upon meditation in Buddhism, with the aim to develop mindfulness, concentration, and insight, which constitute the third division (Samadhi or Dhyana) of the Noble Path. Several different meditation techniques have been developed among the different Buddhist schools, and these have been increasingly embraced by many non-Buddhists as well. Some meditation practices emphasize on the concentration of attention with the use of mantras (sounds or phrases used repetitively). Others focus on the development of mindfulness to cultivate a nonjudgmental awareness of the inner and outer world in the present moment.[12] Meditation practice can positively influence the experience of chronic illness and can serve as a primary, secondary, and/or tertiary prevention strategy.[13] Mindfulness techniques have received the greatest attention from a health perspective.

Mindfulness practice

Mindfulness or Sati is an ancient Buddhist practice that refers to a state of awareness of internal events, in the present moment, without judgment or attempts to control or suppress them or respond to them.[14] Some of these mindfulness practices are based on the body such as breathing meditation, sitting or walking meditation, or reflection on various body parts while others are based on feelings, both pleasant and unpleasant where one accepts the feeling but rather than dwelling in it, lets it come and pass like clouds in the sky.

Anapanasati or “mindfulness of breathing” is the most widely practiced and refers to a silent continuous observation of breath coming in and out with steady attention. The practitioner observes how the mind drifts away to body sensations (such as pain or muscle tension) and thoughts or emotions and gently brings it back to breathing. It does not involve regulation or control of breath, but only observation, thus differing from Pranayama.[15] This form of Attention Training helps cultivate right awareness and increases clarity and acceptance of our present moment reality. An example of mindfulness of breathing is highlighted in Box 1.

Box 1.

The practice of mindfulness of breathing

Large population-based studies indicate that the practice of mindfulness is strongly correlated with better perceived health and well-being.[16] Such meditation techniques are excellent tools of stress reduction and have been utilized by psychiatrists and psychologists to aid management of a variety of health conditions such as depression and anxiety.[17,18] Several contemporary Buddhist meditation teachers have integrated the healing aspects of these mindfulness meditation practices with psychological awareness, healing, and well-being and attempted to keep these practices secular.[9] Meditation influences brain systems involved in attention, awareness, memory, sensory integration, and cognitive regulation of emotion.[19] Neuroimaging studies suggest that mindfulness practices are associated with changes in anterior cingulate cortex, insula, temporoparietal junction, and frontolimbic network.[20]

Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and dialectical behavioral therapy are cognitive and psychological therapies which have been used in a structured manner as an adjunct in several chronic disorders. MBSR is typically an 8-week group program which focuses on training in a variety of mindfulness meditation practices.[21] MBSR has been studied in depression, anxiety, chronic pain syndromes, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, migraine, and substance abuse, with significant improvements reported in pain, mood, and psychological distress.[22,23,24,25] The diagnosis of diabetes and/or its complications is a major life stress. Adapting to daily treatment needs requires significant coping at physical, emotional, and psychological levels. Individuals with diabetes have been reported to have high levels of anxiety, depression, and eating disorders and a higher social burden or stigmatization.[12] Studies suggest that depression tends to be more severe and often untreated in diabetics with a high rate of relapse.[26] MBSR is associated with improvement in depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in diabetics, which may translate to better metabolic control and a healthier state of mind while living with a chronic illness.[27,28,29] Significant improvements in glycemic control, blood pressure control, and arterial stiffness have been demonstrated with walking meditation as compared to traditional walking exercise in type 2 diabetic individuals.[30]

Meditation influences and modulates the activity of the brain and autonomic nervous system, with reduction in sympathetic tone and increase in parasympathetic activity, and has been associated with cardiorespiratory synchronization.[31] Mindfulness was associated with reduced myocardial oxygen consumption and had a strong positive effect on cardiovascular modulation by decreasing vasomotor tone, vascular resistance, and ventricular workload.[32] Mindfulness-based techniques have been found helpful in chronic painful diabetic neuropathy and substance abuse.[33,34] In patients with chronic kidney disease, mindfulness meditation resulted in greater reduction in systolic and diastolic BP, mean arterial pressure, and heart rate and lower respiratory rate.[35] Such techniques would also be of great utility for family members and caregivers of diabetic individuals who have to cope with the stress of the disease and its complications.

The Brahma viharas/four abodes

Another important aspect of Buddhist meditation is the practice of the Brahma viharas or the Four immeasurables (also called four abodes). These include loving-kindness (metta or maitri), compassion (karuna), empathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha). Loving-kindness refers to goodwill toward all including oneself, compassion is identifying suffering of others as one's own, empathetic joy is feeling of joy because others are happy, and equanimity is serenity and treating everyone impartially. Loving-kindness and equanimity meditation are beginning to be used in a wide array of research in the fields of psychology and neuroscience. Studies suggest that Metta or loving-kindness helps increase social connectedness, which would help diabetic individuals feel more accepted and less stigmatized in the society and also increase the support network for them and strengthen doctor–patient relationship.[36]

PRAJNA/LIBERATING INSIGHT

The aim of meditation is twofold – to develop calmness or serenity (samatha) and insight (vipassna). Vipassna focuses on generation of Prajna or liberating insight, which is the knowledge of the true nature of existence. For a Buddhist follower, this means the wisdom of the dharma, karma, suffering, impermanence, nonself, and dependent origination. Dukkha or suffering, anicca or impermanence, and anatta or nonself are known as the Three Marks of Existence. A diabetic individual must also be encouraged to understand the concept of dharma and karma in diabetes management.

Karma in diabetes

Like most Eastern philosophies, the concept of “karma” is fundamental to Buddhism. Karma in a broad sense refers to “action with intent” and good deeds beget good karma, while bad deeds lead to building up of bad karma, the fruit of which may be borne in this life or in subsequent lives. Several longitudinal studies of diabetes management, both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, have described “Glycemic Legacy” which can be correlated to “Metabolic karma.”[37] Individuals with good glycemic control in the initial years of diabetes diagnosis carry a good glycemic legacy/karma for several decades even after the control has worsened with lower rates of micro- or macro-vascular complications than those individuals who have accumulated a higher glycemic burden/karma in early years.

At the same time, karma should not be taken as a “judgment” for bad deeds as per Buddhist philosophy. Similarly, a diabetes person should not interpret the need for insulin injections or development of complications as a punishment for their bad behavior in the past. Karma in Buddhism is a flexible, fluid, and dynamic process and not rigid or fatalistic, which is very relevant to diabetes management since one can make efforts at any time to change disease outcomes – it is never too late to act. Buddhism can help encourage patients to act with skill and clarity in the present moment so that they can change their outcomes in the future.

Another important tenet in relation to karma is the “transfer of merit” or transindividual karma – a person can transfer one's good karma to others. This encourages family members and caregivers to support persons with diabetes. Diabetes health-care professionals who work selflessly for their patients too accumulate good karma in the process and can transfer the same to the individuals under their care. In gestational diabetes, inadequate glycemic control can lead to fetal imprinting and future risk of chronic metabolic and cardiovascular diseases in the offspring – an example of transgenerational karma.

Impermanence/Anicca

Any illness is associated with a sense of loss of control. The diabetic individual may feel stressed about blood glucose fluctuations, neuropathic pain, diabetic gastroparesis, or diarrhea and other complications.

“Vedana samosarana sabbe dhamma”

Everything that arises in the mind is accompanied by sensation (vedana) and these sensations can produce suffering. As one repeatedly observes the sensations during meditation and notices how they keep changing constantly, the habit of reaction is replaced by an experience of the truth of impermanence.

In his last sermon before his demise (parinirvana), Buddha taught about this impermanence:

“All composite things are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence.”

The perspective of impermanence and constant flux allows people to see their symptoms in a new light without fear and anxiety building up. The understanding of impermanence (sampajanna) can help patients cope up with the diagnosis of diabetes and its complications such as loss of kidney, vision, or a limb. It may also help the family members of deceased patients during grieving – whatever has the nature of arising and has the nature of cessation.

Dependent origination/Pratityasamutpada

The Buddhist worldview is holistic and based on a belief in the interdependence of all phenomena and a correlation between mutually conditioning causes and effects. “When this is, that is; this arising, that arises. When this is not, that is not. This ceasing, that ceases.” Health is, therefore, understood as an expression of harmony within oneself, with society and natural environment. Healing in Buddhism is not merely the treatment of measurable symptoms, but an expression of the combined efforts of mind and body to overcome disease. This is understood as Holistic Care in modern medicine. The law of karma in metabolic health and its effects has been elucidated in the earlier section.

Most patients find it difficult to comprehend the link between diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other comorbidities. The insight of dependent origination can help patients understand how diabetes and its comorbidities and complications are inter-related and are not distinct independent disorders, and hence the need for comprehensive and multifactorial management in diabetes.

CONCLUSION

This brief communication offers a perspective on how the eternal wisdom of Buddhism provides inspiration for optimal diabetes care. The basic teachings of Buddhism can be assimilated in modern medicine to help improve the health and well-being of the patient. This knowledge is as important for persons with diabetes, as it is for their health-care providers. We hope that this publication will stimulate more discussion and facilitate improvement in the quality of diabetes care across the Buddhist and non-Buddhist world.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edward JT. North Chelmsford, Massachusetts, U.S.A: Courier Corporation; 1949. The Life of Buddha as Legend and History. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinay K. Development and Spread of Buddhist Art and Traditions in South East Asia. International Conference on Buddhism and Jainism in Early Historic Asia. 16th – 17th February. University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka: Centre for Asian Studies; 2017. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey P. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013. An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuramasuwan B, Howteerakul N, Suwannapong N, Rawdaree P. Diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, daily life activities, food and beverage consumption among Buddhist monks in Chanthaburi Province, Thailand. International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries. 2013;33:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijewardena DA. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 25];Buddhist Monks Risk Contracting Diabetes. The Island: Sunday Island epaper. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wijesinghe S, Mendelson C. The health behavior of Sri Lankan Buddhist nuns with type 2 diabetes: Duty, devotion, and detachment. J Relig Health. 2013;52:1319–32. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9592-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundberg PC, Thrakul S. Type 2 diabetes: How do Thai Buddhist people with diabetes practise self-management? J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:550–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sowattanangoon N, Kochabhakdi N, Petrie KJ. Buddhist values are associated with better diabetes control in Thai patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38:481–91. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.4.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aich TK. Buddha philosophy and western psychology. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S165–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fronsdal G. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Shambhala Publications, Inc; 2009. The Dhammapada: A New Translation of the Buddhist Classic with Annotations. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurung RA. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO Publishers; 2014. Multicultural Approaches to Health and Wellness in America. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitebird RR, Kreitzer MJ, O’Connor PJ. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2009;22:226–30. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.22.4.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonadonna R. Meditation's impact on chronic illness. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:309–19. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabat-Zinn J. New York, USA: Delacourt; 1990. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou T, Wu C, Fan X. The clinical value, principle and basic practical technique of mindfulness intervention. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28:121–30. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bränström R, Duncan LG, Moskowitz JT. The association between dispositional mindfulness, psychological well-being, and perceived health in a Swedish population-based sample. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16:300–16. doi: 10.1348/135910710X501683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen M. Mindfulness-based interventions: An emerging phenomenon. Mindfulness. 2011;2:186–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Follette V, Palm KM, Pearson AN. Mindfulness and trauma: Implications for treatment. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;24:45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acevedo BP, Pospos S, Lavretsky H. The neural mechanisms of meditative practices: Novel approaches for healthy aging. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2016;3:328–39. doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U, et al. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:537–59. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R, Sellers W. Four-year follow-up of a meditation-based program for the self-regulation of chronic pain: Treatment outcomes and compliance. Clin J Pain. 1986;2:159–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review of the evidence. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:83–93. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011;152:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil SG. Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation (Vipassana) in the management of chronic low back pain. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:158–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1350–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katon WJ. The comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and depression. Am J Med. 2008;121:S8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenzweig S, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, Edman JS, Jasser SA, McMearty KD, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is associated with improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopf S, Oikonomou D, Hartmann M, Feier F, Faude-Lang V, Morcos M, et al. Effects of stress reduction on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes patients with early kidney disease - Results of a randomized controlled trial (HEIDIS) Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2014;122:341–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann M, Kopf S, Kircher C, Faude-Lang V, Djuric Z, Augstein F, et al. Sustained effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction intervention in type 2 diabetic patients: Design and first results of a randomized controlled trial (the Heidelberger Diabetes and Stress-Study) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:945–7. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gainey A, Himathongkam T, Tanaka H, Suksom D. Effects of Buddhist walking meditation on glycemic control and vascular function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerath R, Barnes VA, Crawford MW. Mind-body response and neurophysiological changes during stress and meditation: Central role of homeostasis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014;28:545–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.May RW, Bamber M, Seibert GS, Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Leonard JT, Salsbury RA, et al. Understanding the physiology of mindfulness: Aortic hemodynamics and heart rate variability. Stress. 2016;19:168–74. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2016.1146669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teixeira E. The effect of mindfulness meditation on painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in adults older than 50 years. Holist Nurs Pract. 2010;24:277–83. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181f1add2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Howard MO, Garland EL, McGovern P, Lazar M. Mindfulness treatment for substance misuse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:62–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J, Lyles RH, Bauer-Wu S. Mindfulness meditation lowers muscle sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in African-American males with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R93–101. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00558.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutcherson CA, Seppala EM, Gross JJ. Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion. 2008;8:720–4. doi: 10.1037/a0013237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalra S, Ved J, Baruah MP. Diabetes destiny in our hands: Achieving metabolic karma. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:482–3. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_571_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]