ABSTRACT

Lemierre’s syndrome is a condition characterised by suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular (IJ) vein following a recent oropharyngeal infection, with resulting septicaemia and metastatic lesions. It is strongly associated with Fusobacterium necrophorum, a Gram-negative bacilli. Key to early diagnosis is awareness of the classical history and course of this illness, and therefore to ask about a history of recent oropharyngeal infections when a young patient presents with fever and rigors. Diagnosis can be confirmed by showing thrombophlebitis of the IJ vein, culturing F necrophorum from normally sterile sites or demonstrating metastatic lesions in this clinical setting. The cornerstone of management is draining of purulent collection where possible and prolonged courses of appropriate antibiotics. In this article, we review a case study of a young man with Lemierre’s syndrome and discuss the condition in more detail.

KEYWORDS: Lemierre, Lemierre’s syndrome, Fusobacterium necrophorum, suppurative thrombophlebitis

Case history

A 21-year-old man initially presented with a 1-week history of sore throat, cough productive of brown sputum, odynophagia, fever, rigors and right-sided neck, ear and pleuritic chest pain. He was a smoker of 10 cigarettes a day and a regular cannabis user, but denied intravenous drug use. He was normally fit and well with no past medical history, regular medications or family history of note. On examination, he had unilateral swelling of the right tonsil with visible exudate and tender cervical lymphadenopathy, worse on the right. He was pyrexial at 38.6°C and tachycardic at 120 beats per minute. His other observations were normal. Blood tests showed a leucocytosis and raised C-reactive protein, thrombocytopaenia, hyponatraemia and raised bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. His chest radiograph was reported as showing small patches of inflammatory-type shadowing bibasally. He was diagnosed with quinsy. The abscess was drained and he was treated with IV benzylpenicillin, metronidazole and dexamethasone. He improved clinically and was discharged after 2 days. His blood cultures grew Gram-negative rods and microbiology advised at least 2 weeks antibiotics with outpatient follow-up.

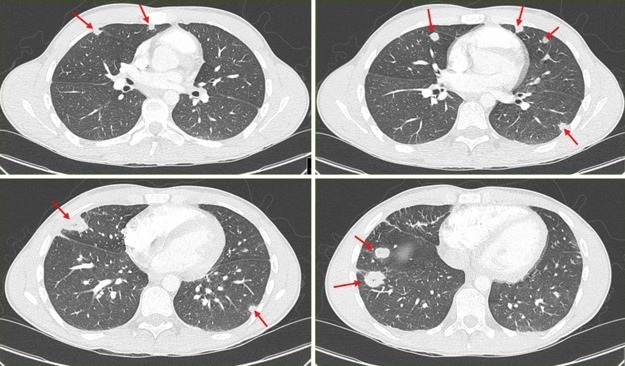

He re-presented 2 days later, complaining of bilateral pleuritic lower chest pain, associated with fever and dyspnoea. His observations were within normal limits. Bloods again showed a leucocytosis with a raised alanine transaminase, raised D-dimer and hypoalbuminaemia. A liver autoantibody screen and HIV test were both negative. Chest radiograph showed bilateral nodular opacities, worst in the right lower zone. A computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram showed bilateral multiple peripheral nodular lesions, some of which demonstrated internal cavitation (Fig 1). There were also small subpleural patches of consolidation and mild pleural effusion at right lung base and no evidence of pulmonary embolism. An ultrasound Doppler scan of the neck was performed showing patent internal jugular veins with no evidence of thrombus. Echocardiogram showed no obvious vegetations and blood cultures grew Fusobacterium necrophorum in the anaerobic bottle after 2 days, sensitive to erythromycin, penicillin and metronidazole. He was treated with piperacillin/tazobactam and metronidazole, analgesia and IV fluids, following which he improved sufficiently to be discharged home.

Fig 1.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA). Multiple peripheral nodular lesions are indicated with red arrows, some of which (bottom row) demonstrate internal cavitation.

Discussion

Lemierre’s syndrome is a condition characterised by four key elements:

primary oropharyngeal infection within 4 weeks

suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular (IJ) vein

metastatic septic emboli

causal association with F necrophorum.

Epidemiology

Lemierre’s syndrome is typically an illness of previously healthy, young adults, with 89% of patients between 10 and 35 years of age.1 With the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, the reports of Lemierre’s syndrome fell dramatically, so much so that it earned the pseudonym of the ‘forgotten disease’. Although Lemierre’s syndrome is still an uncommon illness, there is some evidence that this condition is seeing a resurgence.2–4 This rise in incidence is likely a reflection of two main changes in medical practice: first, restriction in the use of antibiotics to treat upper respiratory tract infections, and second, tightening of the criteria for tonsillectomy. Increased awareness of this condition is required to rapidly identify and manage this illness, particularly as delay in commencing appropriate antibiotic therapy has been shown to be associated with greater mortality.

Pathogenesis

Lemierre’s syndrome is causally associated with F necrophorum, an anaerobic Gram-negative, non-spore forming bacillus. It has been detected in blood cultures of 86% of patients with Lemierre’s syndrome. Infection of the tonsil and the lateral pharyngeal space is typically polymicrobial, with thrombophlebitis in the draining tonsillar veins being the critical event when F necrophorum emerges as the key organism. A key feature of the pathogenesis of F necrophorum is the ability to stimulate clot formation via production of haemagglutinin, and multiply within the clot with subsequent embolic spread.

The most common site of embolisation is to the lungs, with 85–92% of patients with Lemierre’s syndrome having this. Other sites include to joints, muscles, liver and spleen. Central nervous system involvement occurs far more commonly with primary otogenic infection versus tonsillitis (65% vs 6.2%).

Diagnosis

Lemierre’s syndrome should be suspected in those with a recent history of oropharyngeal infection presenting with fever and rigors, with or without evidence of metastatic lesions, particularly respiratory symptoms (pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea, haemoptysis). Lemierre famously expressed the ease of clinical diagnosis in his seminal paper, and this remains as useful now as it was then:

The appearance and repetition several days after the onset of a sore throat (and particularly of a tonsillar abscess) of severe pyrexial attacks with an initial rigor or still more certainly, the occurrence of pulmonary infarcts and arthritic manifestations, constitute a syndrome so characteristic that mistake is almost impossible.5

Ultrasound Doppler of the IJ vein or CT neck with contrast can be used to detect thrombophlebitis of the IJ vein. Ultrasound is less sensitive, as recently formed thombi have little echogenicity, and it only evaluates tissue above the clavicle; however, it is rapid, non-invasive and relatively inexpensive.

Management

There are two key aspects in the management of Lemierre’s syndrome; draining of collections of pus wherever possible, together with a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotics. There are no controlled trials to guide management, but most sources recommend between 2–6 weeks of antibiotics in total. F necrophorum has consistently shown evidence of resistance to erythromycin, with reasonable empirical choices including a penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitor, penicillin plus metronidazole, or a carbapenam, which should then be tailored to sensitivities (Box 1).

Box 1. Appropriate empirical antibiotic regimens.

| > Penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitor |

| > Penicillin plus metronidazole |

| > Carbapenam |

The use of anticoagulation to prevent extension of thrombosis or further embolisation has been more frequently used in cases with extension of thrombus into the sigmoid or cavernous sinus.6

Surgical ligation or excision of the internal jugular vein may be indicated in patients with persistent septic embolisation or extension of thrombus despite aggressive medical therapy for an adequate period of time.

Conclusion

Lemierre’s syndrome is a rare but potentially fatal condition occurring primarily in young, otherwise healthy individuals. It is characterised by a septic illness with metastatic lesions following an oropharyngeal infection, most commonly pharyngitis, and suppurative thrombophlebitis of the IJ vein. It is strongly associated with F necrophorum, a Gram-negative bacillus. Diagnosis is often made through growth of this characteristic bacterium or identification of metastatic lesions or IJ vein thrombophlebitis in this clinical setting. The two key aspects of management are drainage of collections of pus wherever possible and prolonged courses of appropriate antibiotics.

Consent to publish

Consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the clinical details and images in this article.

References

- 1.Riordan T. Human Infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a Focus on Lemierre’s Syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:622–59. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagelskjaer LH. Prag J. Malczynski J. Kristensen JH. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre’s syndrome, in Denmark 1990–1995. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:561–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01708619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagelskjaer LH. Kristensen L. Prag J. Lemierre’s syndrome and other disseminated Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in Denmark: a prospective epidemiological and clinical survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:779–89. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0496-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazier JS. Human infections with Fusobacterium necrophorum. Anaerobe. 2006;12:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;2:701–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stam J. De Bruijn SF. DeVeber G. Anticoagulation for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD002005. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]