ABSTRACT

Compassionate communities as part of the public health approach to end-of-life care (EoLC) offers the possibility of solving the inequity of the difference in provision of care for those people with incurable cancer and those with non-cancer terminal illnesses. The naturally occurring supportive network surrounding the patient is the starting point for EoLC. The network can provide both hands-on care and support to those providing hands-on care. Healthcare professionals can build much stronger partnerships with these supportive networks and transform EoLC at home. Further possibilities of support can be developed through communities, with implementation of the Compassionate City Charter.

KEYWORDS: End-of-life care, compassionate communities, public health approach to end-of-life care, Compassionate City Charter

Introduction

The historical development of the modern palliative care movement, from its inception in 1967 with the formation of St Christopher’s Hospice, has largely focused on those people with a diagnosis of incurable cancer. Care has been increasingly professionalised and attempts to address the inequity of end-of-life care (EoLC) for those with a cancer diagnosis compared to those with non-cancer terminal illnesses, has been largely unsuccessful.1

Addressing the needs of patients who have terminal illnesses is often complex and covers multiple domains of symptom control, social environment and care, psychological and emotional distress and spiritual care. A variety of ways exist to elicit which areas are important to patients, with multiple quality of life scores available.2,3 However, when exploring what was most important with carers after bereavement, the most valued help is the care and support of family, friends and neighbours. This frequently does not relate to physical care or emotional support given to patients, but to the strength of the caring network. These networks fulfil a wide variety of functions, ranging from managing the daily necessities of life such as shopping, cooking, cleaning and gardening, to emotional support and friendship which form the natural spectrum of relationships that surround our lives. Bonds of friendship formed through being part of a caring network may be strong and last for years.4

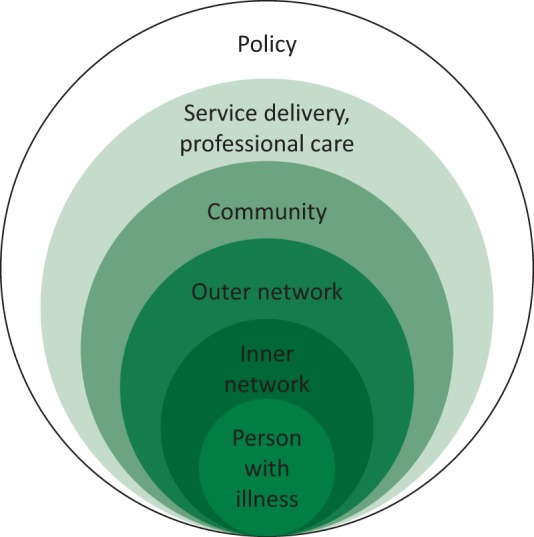

Health professionals can struggle to conceptualise and make best use of caring networks. Circles of care5 (Fig 1) is a way of viewing the overall networks that focuses not just on the patient, but on the main carer and the caring network. Failure to engage with and trust the caring network not only misses an important opportunity for enriching life for patient and carers, it may actually cause significant harm which can exacerbate bereavement reactions.6

Fig 1.

Circles of care.

The public health approach to EoLC and development of compassionate communities offers an opportunity to address the inequity of EoLC irrespective of age, diagnosis or cause of death. This approach also has a practically based continuity between chronic disease, EoLC and bereavement. It has been gaining increasing international interest since the publication of Health promoting palliative care by Professor Allan Kellehear.7 Despite the relatively short history of this area, there is increasing evidence for the effectiveness of this approach.8 Through building networks of support in a proactive way, whether among family or friends, neighbourhoods, workplaces or educational institutions, means that much of the work currently done by professionalised services can be done through social support. End-of-life care is everyone’s business as all of us, at some point in our life, will have to care for those closest to us who will die. Through redistribution of roles and redefining of job plans, we can restructure services inclusive of all of EoLC.

Building compassionate networks of support

A common misperception from health and social care professionals about networks of support is that the centre of activity is around the patient. Typically, an inner network of support5 contains two to five people. The person who is unwell may not want to interact with large numbers of people, whether they are family, friends, neighbours, community members or caring professionals. A central focus is therefore looking to build resilient networks of support for the people who fulfil the functions of the inner network. These may be physical care, accompaniment, emotional support or attention to symptom control issues. The outer network is usually more to do with the tasks of life that we all have to complete – the washing, cooking, cleaning, walking the dog and working on the garden. While these tasks seem mundane, support from a number of people can make an enormous difference when building resilient networks. Having someone drop a meal round not only helps in a very practical way, the kindness shown can have a profound impact on patient and carers. In particular, the person with the illness often experiences a sense of burden and the support given by a caring network is a great source of comfort, knowing that those closest to them are cared for as well.

Commonly, when people offer help, the first reaction from patients and carers is ‘No, we are managing fine at the moment.’ This is the opposite of network building. Caring for someone is more akin to a marathon than a sprint. Carers often need some encouragement and explanation about why it is important to say yes to offers of support. In addition, learning the skills of how to ask for help and how to organise a network makes a big difference in building support. Use of electronic software such as Facebook, WhatsApp or Jointly App are useful ways of organising a network through web-based coordination. This can help to keep people informed as to what is happening without having to ring round everyone individually. It is also a method of requesting help from a group without having to ask an individual to do a specific task.

Supportive networks exist wherever there are people, which is everywhere. Building networks of support can therefore happen across the whole spectrum of society, including workplaces, educational institutions, churches and temples, neighbourhoods, community centres and in health and social care organisations. The succinct essence of this approach is contained in Professor Kellehear’s Compassionate City Charter.9 Joining together healthcare initiatives with civic action helps to create community capacity for caring at end of life, which can be accessed by health and social care organisations. The charter is a way geographical areas can focus on systematically stimulating community resource for end of life at the same time as providing civic incentives and supporting this with policy change. A number of cities within the UK and internationally have started the process of becoming compassionate cities. Although the word cities is taken to mean urban living, in the context of the charter the derivation is from citizen with reference to civic responsibility. This is applicable to everyone and is not limited to urban dwelling.

The strategic direction for EoLC in the UK is contained in the Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care 2015–2020.10 Ambition 6 in this document is ‘communities are prepared to help’. The guidance document contains practical ideas for health and social care organisations on how they can develop resilient networks of support for patients and carers.11 The basis of any such intervention is to explore existing networks through a process of ecomapping. In the context of hospital care, the guidance recommends fitting in with the ‘Safer care bundle’.12 Setting an expected date of discharge early in the patient’s stay in hospital is an opportunity to explore supportive networks to enable to get people home as early as possible. At the same time, it is also an opportunity to begin advance care planning discussions for end of life. These discussions are a form of network building, as it gives the chance for family, friends and relatives to consider what needs to be done should someone choose to die at home. The challenge for hospitals is to ensure that all who have terminal illnesses have the same care irrespective of diagnosis.

Recommendations

In order to set a path of change which addresses the historical inequity of care between those people with cancer and non-cancer terminal diagnoses, services should aim to provide EoLC for all, irrespective of age, diagnosis or cause of death. Supportive networks are the backbone of care outside of hospital. Use of ecomapping and network enhancement as routine in care of chronic illness and end of life. Their use should be built into standard clinical practice, including hospital care.

Although the public health approach to EoLC has been developing over the last 20 years, there is still a need to increase health and social care professionals with familiarity concepts and practice. The guidance document Community Development in End of Life Care – Guidance to Ambition is a basis for developing a programme of adoption of this approach. Included in the guidance are recommendations of how to bridge organisational silos, bringing together professionals and communities across an area. Leading local initiatives across organisational boundaries and into communities through implementation of the Compassionate City Charter is a practical way of achieving this.

Summary

Development of compassionate communities is part of the broader initiative of the public health approach to palliative and end of life care. ‘Communities are prepared to help’ is ambition 6 of the national guidance document for end of life care. Hospital teams can participate in this approach, making best use of the enormous resource of community support, which is in keeping with principles of good care and efficient patient flow.

References

- 1.Abel J. Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6:21–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearns T. Cornally N. Molloy W. Patient reported outcome measures of quality of end-of-life care: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2017;96:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milnes S. Corke C. Orford N, et al. Patient values informing medical treatment: a pilot community and advance care planning survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017:bmjspcare-2016-001177. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horsfall D. Yardley A. Leonard R. Noonan K. Rosenberg JP. NSW: Western Sydney University; 2015. End of life at home: Co-creating an ecology of care. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel J. Walter T. Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013:bmjspcare-2012-000359. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg JP. Horsfall D. Leonard R. Noonan K. Informal care networks’ views of palliative care services: Help or hindrance? Death Stud. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2017.1350216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellehear A. Health-promoting palliative care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality. 1999;4:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallnow L. Richardson H. Murray SA. Kellehear A. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:200–11. doi: 10.1177/0269216315599869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellehear A. The Compassionate City Charter. Compassionate Communities: Case Studies from Britain and Europe. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National End of Life Care Partnership Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care. NELCP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abel J SL. Community development in end of life care – guidance to ambition. London: NCPC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emergency Care Improvement Programme The SAFER Patient Flow Bundle. Available from. https://improvement.nhs.uk/uploads/documents/the-safer-patient-flow-bundle.pdf . [Google Scholar]