Abstract

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) is a small secreted protein that exhibits a structure similar to the proangiogenic subgroup of the CXC chemokine family. Recently, accumulating evidence suggests that chemokines play a pivotal role in cancer progression and carcinogenesis. We examined the expression levels of 7 types of ELR+ CXCLs messenger RNA (mRNA) in 264 clinical samples. We found that CXCL2 expression was stably down-regulated in 94% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) specimens compared with paired adjacent normal liver tissues and some HCC cell lines. Moreover, CXCL2 overexpression profoundly attenuated HCC cell proliferation and growth and induced apoptosis in vitro. In animal studies, we found that overexpressing CXCL2 by lentivirus also apparently inhibited the size and weight of subcutaneous tumours in nude mice. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CXCL2 induced HCC cell apoptosis via both nuclear and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. Our results indicate that CXCL2 negatively regulates the cell cycle in HCC cells via the ERK1/2 signalling pathway. These results provide new insights into HCC and may ultimately lead to the discovery of innovative therapeutic approaches of HCC.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell proliferation, CXCL2, ERK1/2, HCC

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent cancer types and the major cause of cancer-related deaths (1, 2). Fifty-five percent of HCC cases occur in China due to liver cirrhosis and high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection (3). Although significant advances in HCC diagnosis and surgical techniques, the 5-year survival rate after surgical resection or liver transplantation remains unsatisfactory given frequent tumour recurrence and metastasis (4, 5). Therefore, the molecular pathogenesis of HCC must be characterized to identify novel therapeutic targets and predictive biomarkers to improve treatment response and HCC prognosis.

A recent study demonstrates that inflammation was identified as a new hallmark of cancer (6). Cancer-related inflammation drives tumour progression and especially aids tumour cell survival and proliferation (7). Most HCC cases are caused by hepatitis B virus infection in China, indicating a possible association between HCC progression and inflammation (8). However, at present, the underlying mechanisms of inflammation and HCC progression remains incompletely characterized.

Chemokines are small soluble proteins that can induce chemotaxis in multiple cell types, such as tumour cells, leukocytes and endothelial cells (9). Recent studies have revealed that chemokines and their receptors are important components involved in inflammatory conditions and cancer, which can lead to the failure of treatment (10, 11). This chemokine superfamily is divided into four subfamilies based on the arrangement of the N-terminal cysteine residues of the mature peptide (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/2920). The C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) is a member of the CXC subfamily and encodes secreted proteins involved in immunoregulatory and mainly recruits neutrophils. Some reports demonstrated that CXCL2 is overexpressed in breast (12), colon (13), prostate (14) and bladder cancer (15), which promotes HCC cell invasion and migration (16). However, CXCL2 is expressed at sites of inflammation and may suppress hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation. On the whole, the other biological function of CXCL2 in HCC remains uncharacterized.

In the current study, we detected the expression pattern of CXCL2 in HCC tissues and different HCC cell lines. Then, highly metastatic cell lines (MHCC97H and HCCLM3) were transfected with CXCL2 cDNA. Meanwhile, we investigated the role of CXCL2 in regulating HCC biology by evaluating the expression, potential function and mechanisms.

RESULTS

CXCL2 expression is down-regulated in HCC tumour tissues and correlated with tumour number and poor prognosis

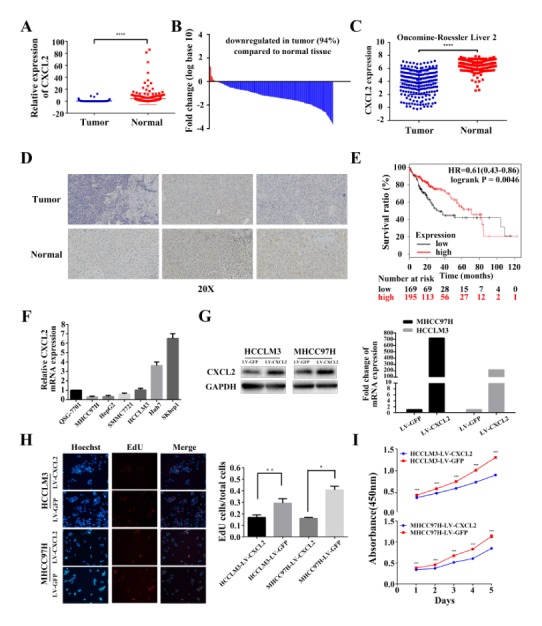

We detected CXCL2 expression levels in HCC tissues by RT-PCR and verified that CXCL2 was apparently down-regulated in HCC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 1A, B). Immunohistochemical analysis of CXCL2 expression in paired HCC and normal liver tissue showed consistent results (Fig. 1D). Based on median value, patients were segregated into high CXCL2 expression and low CXCL2 expression groups. Association analysis revealed that expression of CXCL2 did not correlate with age, gender, histopathologic grading, preoperative AFP level or tumour size. Unlike expectations, high expression of CXCL2 was significantly correlated with multiple tumour numbers (P = 0.002, Table 1). Using Oncomine analysis, we investigated the mRNA levels of CXCL2 in human HCC (Fig. 1C). The similar statistical result was found in paired HCC and normal tissues. Furthermore, we assessed the correlation between CXCL2 and survival rates of HCC patients. The Kaplan-Meier plotter online database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) was used to analysis the correlation of overall survival between CXCL2 expression levels. Expectedly, we found that compared to the 5-year overall survival rates in HCC patients with low CXCL2 expression was significantly lower than those with higher CXCL2 expression (P = 0.0046, Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Relative CXCL2 expression levels in hepatocellular carcinoma and normal tissues and its inhibition of cell proliferation in HCC cells. (A) In 264 pairs of tissues, CXCL2 expression was apparently down-regulated in tumours compared with adjacent liver tissues. ****P < 0.0001. (B) In the majority of HCC tissues (91%), CXCL2 mRNA levels were reduced. (C) Oncomine data (www.oncomine.org) showed under-expression of CXCL2 in HCC and paired normal liver tissues. ****P < 0.0001. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of CXCL2 expression in three paired HCC and normal liver tissue. (E) Association between overall survival and CXCL2 expression in HCC patients. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. (F) CXCL2 expression was reduced in MHCC97H, HepG2, HCCLM3 and SMMC7721. (G) Western blot and RT-PCR confirmed CXCL2 mRNA and protein expression in HCCLM3-LV CXCL2, MHCC97H-LV CXCL2 and control group cells. (H) Representative images of EdU incorporation assays. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. (I) Cell viability was analysed by the CCK-8 assay. ***P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological correlation of CXCL2 expression in human HCC

| Variables | Tumor CXCL2 expression | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Low | High | ||

| Age | |||

| ≤ 50 years | 30 | 28 | 0.741 |

| > 50 years | 49 | 51 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 3 | 6 | 0.303 |

| Male | 76 | 73 | |

| Preoperative AFP level | |||

| ≤ 400 ng/ml | 44 | 41 | 0.632 |

| > 400 ng/ml | 35 | 38 | |

| Histopathologic grading | |||

| Well + moderately | 41 | 31 | 0.110 |

| Poorly | 38 | 48 | |

| Tumor size | |||

| ≤ 5 cm | 24 | 29 | 0.400 |

| > 5 cm | 55 | 50 | |

| Tumor number | |||

| Single | 68 | 51 | 0.002 |

| Multiple | 11 | 28 | |

HCC patients were segregated into CXCL2- high/low expression groups based on median value.

Statistical analyses were performed with chi-square test.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

CXCL2 is down-regulated in HCC cell lines, inhibiting HCC cell proliferation in vitro

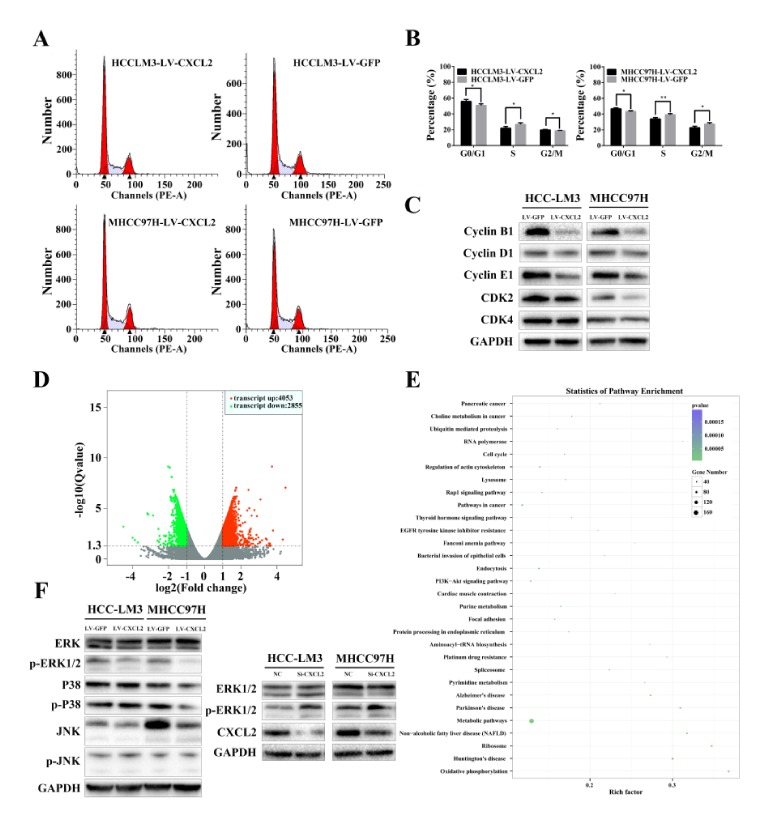

To determine whether CXCL2 expression is associated with liver cancer progression, we used real-time PCR to analyse CXCL2 expression levels in six liver cancer cell lines and normal hepatocytes (QSG7701). Of the HCC cell lines, four (MHCC97H, HCCLM3, HepG2 and SMMC7721) expressed lower levels of CXCL2 compared with the normal liver cells line (QSG7701) (Fig. 1F). Up-regulation of CXCL2 in the stably transfected HCCLM3 and MHCC97H cells was confirmed by Western blot and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1G). In EdU assay, the percentage of cells stained with EdU was dramatically decreased in CXCL2-overexpressing cells (Fig. 1H). Overexpression of CXCL2 also significantly suppressed HCCLM3 (P < 0.001) and MHCC97H (P < 0.001, Fig. 1I) cell viability as examined by CCK-8 assays. These results implied that CXCL2 may inhibit cell proliferation in liver cancer. Moreover, flow cytometry exhibited cell cycle alterations due to CXCL2 overexpression (Fig. 2A). We detected that CXCL2 overexpression decreased the percentage of S phase cells and increased the percentage of G0/G1 phase and G2/M phase cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 2B). To explain cell cycle alternations at the molecular level, we detected cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), cyclin B1, cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 (Fig. 2C). The results suggested that the level of CDK2 and cyclin B1, cyclin E1 was obviously decreased in MHCC97H-LV CXCL2 cells and reduced (not significantly) in HCCLM3-LV CXCL2 cells.

Fig. 2.

The effects of CXCL2 overexpression on the cell cycle. (A) Representative FACS images of HCCLM3 and MHCC97H cells with LV-CXCL2 or LV-GFP. (B) Alterations in cell cycle distribution were analysed. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. (C) Western blot analysis revealed the effect of CXCL2 on the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase and cyclin proteins. (D) Gene expression microarray showed 6908 differentially expressed genes. (E) The KEGG analysis indicated that CXCL2 regulated metabolic, PI3K—Akt signalling, cell cycle, pathways and so on. (F) CXCL2 reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HCC cells.

CXCL2 regulates HCC cells proliferation via ERK1/2 pathways

We used gene expression microarray to investigate which signalling pathways influence HCC cell proliferation induced by up-regulation of CXCL2 in MHCC97H. The 6908 differentially expressed genes included 4053 up-regulated genes and 2855 down-regulated genes comparing with control MHCC97H cells (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis showed that CXCL2 could regulate metabolic, PI3K—Akt signalling, cell cycle and pathways in cancer (Fig. 2E). We assayed several pathways. Inhibition was examined by the analysing the phosphorylation state of ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signalling which can be activated by chemokine receptors. As shown in Fig. 2F, CXCL2 did not affect JNK or p38 phosphorylation in HCC cells. However, the results indicated that CXCL2 expression was negatively correlated with ERK1/2 activation in MHCC97H and HCCLM3 cells. Expectedly, down-regulation of CXCL2 in HCC cells by siRNA increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which was up-regulated in CXCL2 knockdown cells (Fig. 2F). These data suggested that inactivation of the ERK1/2 pathway by CXCL2 in HCC cells may represent the mechanism for its anti-tumour effect.

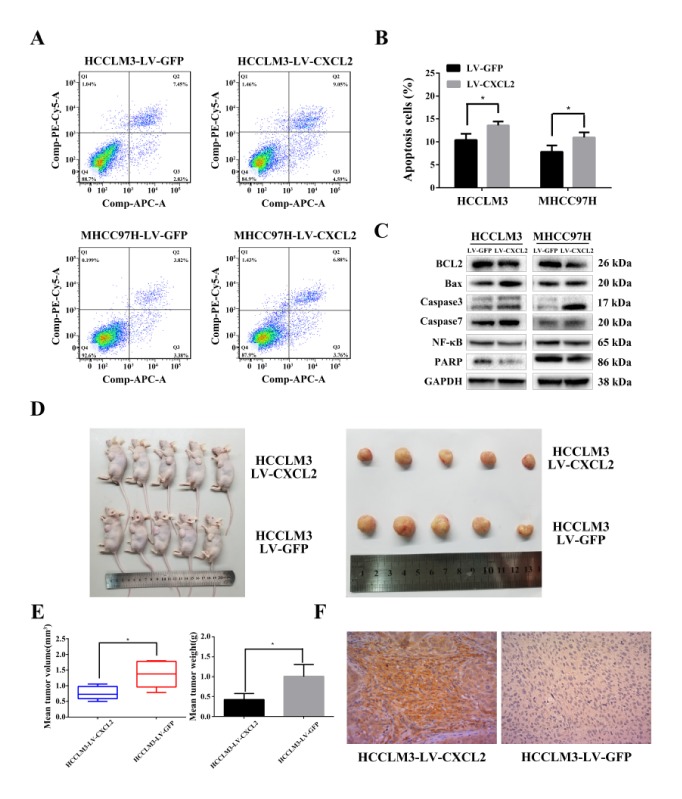

Overexpression of CXCL2 enhances cell apoptosis

Attenuating cell proliferation in tumours is typically correlated with cell death. Therefore, we detected the level of apoptosis in CXCL2-transfected cells using Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD double staining and flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). Compared with LV-GFP, the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was increased in HCCLM3-LV CXCL2 cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 3B). This phenomenon was also observed in MHCC97H cells with LV-CXCL2 (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

CXCL2 induces apoptosis in HCC cell lines and inhibits the growth of tumours in vivo. (A) Apoptosis rates of HCC cells transfected with CXCL2 compared with control as assessed by flow cytometry. (B) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis cells (Q2 + Q4, *P < 0.05). (C) Protein expression of pro-apoptosis mediators and anti-apoptosis regulators in HCC cells were determined by Western blot. (D) Photographic images of the subcutaneously formed tumour tissues. (E) LV-CXCL2-transfected HCCLM3 exhibited significantly reduced tumour volume and weight. *P < 0.05. (F) Representative images of CXCL2 protein expression as assessed by immunohistochemistry.

To explain the underlying molecular mechanism of apoptosis, we detected relative protein expression of pro-apoptosis proteins (Bax, caspase-3 and -7), anti-apoptosis proteins (Bcl-2, nuclear enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and p65 subunit of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB p65)) (Fig. 3C) in stably transfected MHCC97H and HCCLM3 cells.

CXCL2 overexpression increased pro-apoptosis protein (Bax, caspase-3 and -7) levels and degradation of PARP and Bcl-2, indicating that CXCL2 enhance apoptosis via caspase-dependent pathways. Meanwhile, down-regulated NF-κB p65 indicated that CXCL2 may induce apoptosis through nuclear pathways. Collectively, these results suggested that CXCL2 induced HCC cells apoptosis via the mitochondrial and nuclear apoptosis pathways.

CXCL2 overexpression inhibits tumour growth in nude mice

To explore the function of CXCL2 overexpression on HCC growth in nude mice, we injected subcutaneously CXCL2-transfected HCCLM3 cells and control cells into nude mice (five animals per group). After six weeks, all mice were sacrificed and the tumours were harvested (Fig. 3D). Compared with the control groups, LV-CXCL2 transfected mice presented apparently decrease in tumour weight and volume (Fig. 3E). Finally, tumours were dissected into sections to examine CXCL2 expression by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3F).

DISCUSSION

Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammation should be considered a new feature of cancer (6). Recent studies have revealed that chemokines and their receptors play crucial roles in chronic inflammation and cancer (17, 18). To explore which chemokines played a crucial role in inflammation and cancer progression, we investigate the RNA expression levels of seven types of ELR+ CXCLs in 264 clinical samples. We demonstrate that CXCL2 was down-regulated in HCC tissues. The overall survival rates of the high CXCL2 expression group were significantly improved compared with the low CXCL2 expression group. Therefore, we hypothesize that CXCL2 can suppress HCC via some underlying mechanism. Thus, we employed in vitro and in vivo assays and clinical samples to explore the role of CXCL2 in HCC.

CXCL2 was first identified to recruit and activate polymorphonuclear leukocytes as a functional analogue to interleukin 8 (19–21). In contrast to our results, Song et al reported that CXCL2 was overexpressed in the blood samples of HCC patients and promoted proliferation and metastasis in HepG2 and PG5 cells (22). Lu et al verified that CXCL2 increased the proliferation, invasion, and migration of SMMC7721 cells (16). These discrepancies are acceptable due to the differences in cell lines, methods, sample sizes and clinical sample sources used to examine CXCL2 biological functions. Moreover, CXCL2 acts as an oncogene in breast cancer (12) and colon cancer (13) but as a tumour suppressor gene in HCC, which may be due to the different molecular mechanisms of tumour development in different organizational original tumours.

In the current study, we performed functional characterization of CXCL2 in MHCC97H and HCCLM3 cell lines via lentivirus overexpression of CXCL2. Our results revealed that exogenous expression of CXCL2 suppresses cell proliferation by enhancing apoptosis and cell cycle (G1) arrest as determined by flow cytometry. Hence, our present data indicated that CXCL2 plays an important role in HCC progression as a tumour suppressor.

We demonstrated that reduced CDK2, CDK4, cyclin B1, cyclin D1 and cyclin E1, protein levels were correlated with CXCL2 overexpression. These data are consistent with G1 phase arrest demonstrated in LV-CXCL2-infected HCCLM3 and MHCC97H cells. Cyclin D1 binds to CDK4, which promotes G1 progression, resulting in cell proliferation (23, 24). CyclinE1 expression is correlated with and activates CDK2, which is essential for the G1/S transition (25, 26). The Cyclin B1/CDK4 complex plays an important role in the G2/M phase and regulates entry into mitosis (27, 28). Therefore, reduced CDK and cyclin protein levels suggest the anti-proliferation property of CXCL2.

We further determined that ectopic expression of CXCL2 induced apoptosis, which is accompanied by caspase-3, caspase-7 and Bax activation. Caspase-3 and caspase-7 are important elements in mediating cell apoptosis signaling transduction (29, 30). The expression of Bax, a pro-apoptosis Bcl-2 family protein, was increased by CXCL2. Conversely, Bcl-2 which functions as an anti-apoptosis protein was decreased. PARP plays a pivotal role in cell apoptosis and is processed by activated caspase-3 to induce apoptosis. Moreover, NF-κB p65 plays a crucial role in cell proliferation (31). Therefore, CXCL2 overexpression inhibits cell proliferation potentially as a consequence of NF-κB p65 suppression. However, the underlying mechanisms by which CXCL2 regulates HCC cell apoptosis and proliferation during tumourigenesis are not well established. In the current study, we revealed that CXCL2 overexpression inhibits the ERK1/2 pathway, and the importance of ERK1/2 signalling pathway has been described (32).

Moreover, we have unexpectedly discovered in clinical samples that high expression of CXCL2 is associated with multiple tumour numbers. We hypothesize that the effect of a single gene change on the disease at different times is different. We still think that the relationship between CXCL2 and HCC needs more in-depth research with more accurate models to verify the specific mechanism of action of CXCL2 in tumours.

In summary, we determined that CXCL2 expression was down-regulated in HCC. Furthermore, we also determined that ectopic CXCL2 expression suppressed HCC cell proliferation by cell cycle arrest and inducing apoptosis. This study is first to identified CXCL2 as a tumour suppressor gene, and our findings potentially provide a new therapeutic approach for HCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and tissue samples

The local ethics committee approved the experimental protocols. All of the HCC patients got informed written consent. Samples from 264 HCC tissues with matching peritumoural tissues were obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University during 2006 and 2013. Patients’ data were collected in the hospital information collection system.

Cell lines and cell culture

Six HCC cell lines (MHCC97H, SMMC7721, HCCLM3, Huh7, SKhep1, HepG2) and normal hepatocytes (QSG-7701) were purchased from the Liver Cancer Institute of Fudan University (Shanghai, China) and the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 or Minimum Eagle’s medium (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (GEMINI, Woodland, USA). All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Total RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cell lines using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s protocols. CXCL2 expression was determined by RT-PCR, which was performed using a Bio-Rad PCR instrument (CA, USA) and the Takara SYBR Premix Extaq system (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China). The following primers were used: CXCL2 forward: GCTTGTC TCAACCCCGCATC and CXCL2 reverse: TGGATTTGCCATTTTTCAGCATCTT and GAPDH forward: GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT and reverse: GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG.

Lentivirus infection and CXCL2 knockdown model

The LV-CXCL2 and another lentivirus vector encoding LV-GFP, which served as a control, were constructed by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). HCCLM3 and MHCC97H cells were infected by lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 pfu per cell. In addition, 10 μg/ml puromycin was used to select stable transformants.

HCCLM3 and MHCC97H cells were transfected with 50 nM short interfering (si) RNA (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) targeting CXCL2 using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The siRNA sequence: GGGCAGAAAGCTTGTCTCA and negative control siRNA sequence: UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU.

Cell viability assays

The cell proliferation was assessed by a Cell Counting kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Japan). HCCLM3-LV CXCL2 and MHCC97H-LV CXCL2 cells and the control group cells (2 × 103) were plated in 96-well plates. Absorbance was detected at 450 nm. The ethynyl deoxyuridine (EdU) assay (EdU Apollo 567 imaging kit, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) was also used to monitor the cell viability according to the recommendations.

Cell cycle and cell apoptosis analysis

The CXCL2 overexpression or control (LV-GFP) cells were fixed in 75% ethanol at −20°C for > 24 h and stained with Cell Cycle Staining Kit (Multi Sciences, Hangzhou, China). Cell cycle distribution was analysed using BD FACSCantoTM II (BD Biosciences, CA, USA).

The stable transfected cells were stained with the Annexin V-APC/7-AAD Apoptosis kit (Multi Sciences, Hangzhou, China) following the protocols. The stained cells were quantified by flow cytometry.

Tumour xenograft model

Four weeks old male BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Shanghai X-B Animal Ltd, China. HCCLM3 were collected after transfection with LV-CXCL2 or control (LV-GFP). HCCLM3-LV CXCL2 and HCCLM3-LV GFP cells (5 × 106) were suspended in 50 μl of Stroke physiological saline solution and subcutaneously injected into the left flank of immunodeficient mice. After six weeks, all the mice were sacrificed and tumours were collected for analysis. All experiments containing animals according to protocols approved by the Zhejiang Medical Experimental Animal Care Commission.

Western blot analysis

HCC cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and sonicated after 1 h. Protein concentration was detected using the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Equal amounts (25 μg) of proteins were used for separation by electrophoresis in 4–20% ExpressPLUSTMPAGE gels (GenScript, USA) and then transferred to PVDF membranes for 70 minutes. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibody (1:1,000) overnight. Next, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:4,000) for 60 minutes. The immunoreactive bands were detected by EZ-ECL (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The following primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA): anti-cyclin E1 (#20808S), anti-CDK4(#D9G3E), anti-caspase 3 (#9665T), anti-Erk1/2 (#4695T), anti-p-ERK1/2 (#4370T), anti-p38 (#8690T), anti-p-p38 (#4511T), anti-JNK (#9252T) and anti-p-JNK (#4668T). The following primary antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK): anti-CXCL2 (ab139115), anti-cyclin B1 (ab32053), anti-cyclin D1 (ab134175), anti-CDK2 (ab3214), anti-BCL-2(ab32124), anti-Bax (ab32503), anti-caspase 7 (ab32522), anti-NF-κB p65 (ab32536), and anti-PARP (ab74290). Anti-GAPDH (60004-1-Ig) antibodies were obtained from Proteintech (Rosemount, IL, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumours harvested from nude mice and liver tissues from HCC patients were immunostained with CXCL2 primary monoclonal antibody (1:100, sc-365870, Santa Cruze, CA, USA).

Expression microarray

MHCC97H-LV CXCL2 and MHCC97H-LV GFP were used to detect differences in gene expression. We used three biological replicates in this experiment and selected differentially expressed genes between samples by the difference multiples (log2 FoldChange > 1) and significant levels (q-value < 0.05). The KEGG pathway annotation is used to provide signal transduction and disease pathway annotation information for differentially expressed genes. The P value is calculated by Fisher Exact Test and P < 0.05 is used as the significance threshold to obtain statistically significant signal transduction and disease pathways relative to the background. Thereby obtaining distribution information and significance of the gene collection on the KEGG category.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were analysed using SPSS19.0 software (IBM, Chicago, USA). The data were presented as the means ± SD. The statistical significance of differences between two groups was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The correlation between clinicopathological variables and CXCL2 expression was determined using chi-square tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Innovative Research Groups of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.81721091), the Major program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.91542205), the National S&T Major Project (grant no.2017ZX10203205), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (grant no.2017PT32006), the Zhejiang International Science and Technology Cooperation Project (grant no.2016C04003), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no. Y15H160054, grant no. LY15H160017), the Technology Research Program of Jiaxing (grant no. 2015AY23013), and the Charity Foundation of Zhejiang Science and Technology Department (grant no. 2016C37112).

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The Clinical Specimens Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, China) approved for the human specimens used in the current study. All patients got informed consent for the use and storage of their tissue. For the animal experiments, the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, China) was approved, and all treatments performed on animals were according to the ethical standards of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A Asia Pacific Working Party on Prevention of Hepatocellular C. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toso C, Mentha G, Majno P. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: five steps to prevent recurrence. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2031–2035. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Sherman M Practice Guidelines Committee AAftSoLD. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A. Cancer: Inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:36. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. J Clin Immol. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li YW, Qiu SJ, Fan J, et al. Intratumoral neutrophils: a poor prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma following resection. J Hepatol. 2011;54:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reaux-Le Goazigo A, Van Steenwinckel J, Rostene W, Melik Parsadaniantz S. Current status of chemokines in the adult CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;104:67–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth MJ, Cretney E, Kershaw MH, Hayakawa Y. Cytokines in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Immol Rev. 2004;202:275–293. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acharyya S, Oskarsson T, Vanharanta S, et al. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell. 2012;150:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kollmar O, Scheuer C, Menger MD, Schilling MK. Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-2 Promotes Angiogenesis, Cell Migration, and Tumor Growth in Hepatic Metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:263–275. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardaway AL, Herroon MK, Rajagurubandara E, Podgorski I. Marrow adipocyte-derived CXCL1 and CXCL2 contribute to osteolysis in metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32:353–368. doi: 10.1007/s10585-015-9714-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Ye YL, Li MX, et al. CXCL2/MIF-CXCR2 signaling promotes the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and is correlated with prognosis in bladder cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:2095–2104. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Li S, Ma L, et al. Type conversion of secretomes in a 3D TAM2 and HCC cell co-culture system and functional importance of CXCL2 in HCC. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24558. doi: 10.1038/srep24558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang LY, Izumi K, Lai KP, et al. Infiltrating macrophages promote prostate tumorigenesis via modulating androgen receptor-mediated CCL4-STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5633–5646. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubois RN. Role of Inflammation and Inflammatory Mediators in Colorectal Cancer. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2014;125:358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolpe SD, Sherry B, Juers D, Davatelis G, Yurt RW, Cerami A. Identification and characterization of macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:612–616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae COC, Mukaida NA, Matsushima K. Properties of the Novel Proinflammatory Supergene “Intercrine” Cytokine Family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ness TL, Hogaboam CM, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Immunomodulatory role of CXCR2 during experimental septic peritonitis. J Immol. 2003;171:3775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song X, Wang Z, Jin Y, Wang Y, Duan W. Loss of miR-532-5p in vitro promotes cell proliferation and metastasis by influencing CXCL2 expression in HCC. AmJ Trans Res. 2015;7:2254–2261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filmus J, Robles AI, Shi W, Wong MJ, Colombo LL, Conti CJ. Induction of cyclin D1 overexpression by activated ras. Oncogene. 1994;9:3627–3633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paternot S, Bockstaele L, Bisteau X, Kooken H, Coulonval K, Roger PP. Rb inactivation in cell cycle and cancer: the puzzle of highly regulated activating phosphorylation of CDK4 versus constitutively active CDK-activating kinase. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:689–699. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartkova J, Horejsí Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai LH, Harlow E, Meyerson M. Isolation of the human cdk2 gene that encodes the cyclin A- and adenovirus E1A-associated p33 kinase. Nature. 1991;353:174–177. doi: 10.1038/353174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunt T. Under arrest in the cell cycle. Nature. 1989;342:483–484. doi: 10.1038/342483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurse P. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature. 1990;344:503–508. doi: 10.1038/344503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Yuan J. Caspase in apoptosis and beyond. Oncogene. 2008;276:194–6206. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, et al. Ordering the Cytochrome c–initiated Caspase Cascade: Hierarchical Activation of Caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a Caspase-9–dependent Manner. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:281–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer C, Pries R, Wollenberg B. Established and novel NF-κB inhibitors lead to downregulation of TLR3 and the proliferation and cytokine secretion in HNSCC. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11851–11858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]