Abstract

Total Worker Health® (TWH) is a paradigm-shifting approach to safety, health, and well-being in the workplace. It is defined as policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being. The most current TWH concepts are presented, including a description of issues relevant to TWH and introduction of a hierarchy of controls applied to TWH. Total Worker Health advocates for a foundation of safety and health through which work can contribute to higher levels of well-being.

Keywords: Total Worker Health, well-being, wellness, health and safety, meaningful work, job crafting, hierarchy of controls

The boundaries between work life and home life have become increasingly porous. No longer is there a distinct division between the experience of work and the experience of life outside of a workplace. In fact, the very notion of a “workplace” is increasingly dynamic. Workplaces are any location where work is conducted, including motor vehicles, outdoor spaces, sites that shift pending assignments, workers’ homes, dedicated spaces within buildings, and sometimes, combinations of locations.

At the same time, expectations of work are evolving. Workers want fulfilling work—work they find life enhancing. Such work fundamentally protects worker safety and health, and many of these protections are well known to occupational health nurses. However, fulfilling work goes beyond protecting workers and providing paychecks, offering daily opportunities to advance well-being in ways that are meaningful to individual workers. Ideally, fulfilling work broadly promotes the multiple dimensions of health.

In his 1974 landmark book, Working, Studs Terkel captured the oral histories of ordinary individuals talking about their work. Based on his visits with workers who shared their stories, he observed that work is “about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying” (Terkel, 1974, p. xiii). These words are as relevant today as they were more than 40 years ago. Total Worker Health® (TWH) echoes and amplifies this goal, striving to keep workers safe and healthy while advancing their well-being in ways that support a full, rewarding life.

Consideration of the total health of workers is increasingly relevant in the context of work in the 21st century. In 2014, approximately 3 million nonfatal injuries and illnesses were reported by employers, and 4,649 workers died from work-related injuries (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016c). Estimation of deaths from work-related illness remains incomplete, but in 2007, more than 53,000 deaths related to work were reported (CDC, 2016c). The economic toll of these injuries, illnesses, and fatalities based on health care costs and productivity losses has been estimated at US$250 billion (CDC, 2016c).

At the same time, chronic health conditions are on the rise and employers who offer health care benefits will continue to be affected by direct health care costs and indirect costs (e.g., absenteeism and productivity losses). Leading causes of death and disability include chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, cancer, obesity, arthritis (CDC, 2016a), and depression (CDC, 2016b). It has been estimated that “nearly 50% of Americans have one chronic health condition and, of this group, nearly half have multiple chronic conditions” (Hymel et al., 2011, p. 695). Furthermore, it has been reported that more than 80% of health care spending is for chronic health conditions (Hymel et al., 2011). Changes in the workforce (e.g., rising obesity prevalence rates; increasing numbers of older workers; the rising numbers of working women, Hymel et al., 2011; and increasing diversity) also influence the incidence and severity of chronic health conditions and work-related injuries and illnesses.

Because work and workplaces are changing, TWH proposes a new model for thinking about the safety, health, and well-being of workers. First conceived by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in 2003, the TWH concept has evolved over time in response to stakeholder input and trends related to workforce demographics and work itself. This article provides an overview of the most current information on advancing worker well-being through TWH with the aim of informing occupational health nurses about this paradigm-shifting approach to workplace safety and health.

The TWH Concept

Richard Buckminster Fuller observed, “[y]ou never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete” (Laloux, 2014, p. 1). Total Worker Health is a new model that has the potential to do more to fulfill the promise of the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of 1970. The OSH Act gave the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of 1970. The OSH Act gave the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and NIOSH the mandate “to assure so far as possible every man and woman in the Nation safe and healthful working conditions and to preserve our human resources” (OSH Act, 1970, §2(b)). Furthermore, the Act directs that the mandate be fulfilled in part by “… developing innovative methods, techniques, and approaches for dealing with occupational safety and health problems …” (OSH Act, 1970, §2(b)(5)). Total Worker Health is an innovative approach to fulfilling this mandate.

Total Worker Health expands occupational health nurses’ understanding of health and enhances NIOSH’s contribution to overall worker safety, health, and well-being. Total Worker Health is formally defined as policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being (NIOSH, 2016c). First and foremost, the TWH approach is based on the fundamental principle of keeping workers safe as mandated by the OSH Act. First-dollar investments must go toward keeping workers safe and protecting their health. Additional investments that establish workplace policies, practices, and programs to improve and maintain worker health achieves the ultimate goal of creating worker well-being.

Equally important to understanding the TWH concept is knowing what the concept is not. Confusion about the concept has been evident in recent years. The following points emphasize this distinction (NIOSH, 2016b):

TWH is not a “wellness program” implemented without first addressing the specific working conditions that threaten safety and health.

TWH is not a collection of health promotion efforts at a workplace where the very way that work is organized and structured is contributing to worker injuries and illness.

TWH is not consistent with workplace policies that discriminate against or penalize workers for their individual health conditions or create disincentives for improving health.

Issues Relevant to TWH

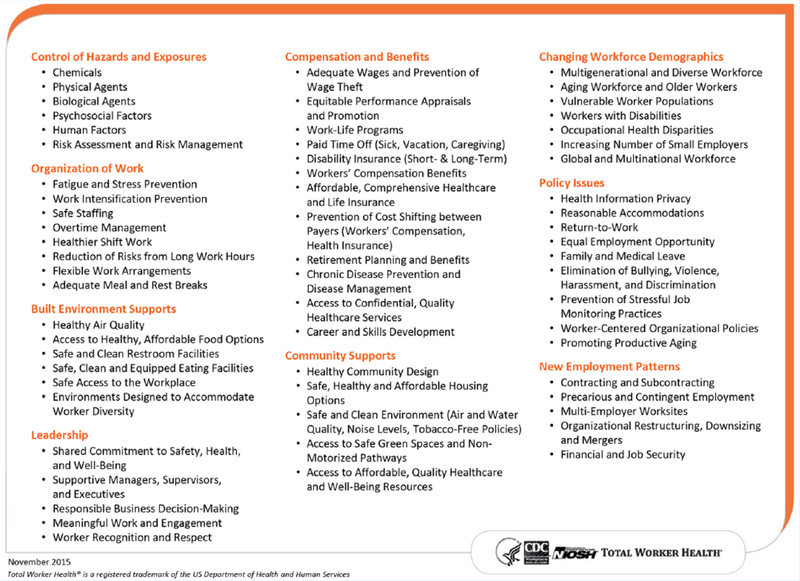

The graphic of issues relevant to TWH (Figure 1) shows the need to consider more than the traditional four disciplines of OSH to remain relevant in today’s work environments. Total Worker Health challenges OSH professionals to consider their roles beyond any constraints that may have inadvertently been created by the traditional disciplines of occupational health nursing, occupational medicine, safety, and industrial hygiene. Addressing this challenge requires a holistic focus upon a broad set of issues affecting worker safety, health, and well-being in the modern U.S. economy.

Figure 1.

Issues relevant to advancing worker well-being through Total Worker Health.

The most familiar issues for OSH professionals, including occupational health nurses, are typically those issues related to control of hazards and exposures and organization of work. Control of hazards and exposures is a broad category that includes chemical, physical and biological agents, psychosocial and human factors, as well as risk assessment and management for identifying and mitigating risks to workers. Examples of interest areas related to organization of work include fatigue and stress prevention, work intensification prevention, management of overtime work, healthier approaches to shift work, and flexible work arrangements. Although these issues form the foundation upon which TWH is achieved, many other issues play a role in advancing worker well-being.

Built environment supports contribute to worker well-being by providing healthy air quality, access to healthy and affordable food options, safe and clean facilities for personal use in the workplace, and environments designed to accommodate worker diversity. Changing workforce demographics, especially the aging workforce, vulnerable worker populations, and workers with disabilities, underscore the importance of accommodating diversity. Community supports also contribute to worker well-being. Safe, healthy, and affordable housing options for workers, work location site selection, healthy community design, and safe and clean environments are consistent with the TWH approach because of the inherent recognition of the health-related implications of porous boundaries between work, home, and community life.

Although it is common for occupational health nurses to manage workers’ compensation claims and benefits related to health care and disability, and oversee case management for workers with illness-related absences and disability claims, untapped areas related to compensation and benefits deserve nurses’ attention to protect worker safety and health and enhance well-being. Paid sick leave is one such issue. Recent NIOSH research found access to paid sick leave is associated with 28% lower injury likelihood when workers with this benefit are compared with workers without paid sick leave (Asfaw, Pana-Cryan, & Rosa, 2012). Other relevant issues related to compensation and benefits include adequate wages and prevention of wage theft, work-life management programs, provision of health care and disability insurance, and retirement planning and benefits. All of these issues contribute to financial security which has long been associated with health and well-being.

Many occupational health nurses are also directly involved in some of the policy issues (e.g., health information privacy, reasonable accommodations, return to work, and family and medical leave) that affect TWH. Beyond these more commonly known issues, other opportunities for occupational health nurses to improve worker well-being include intraorganizational policies related to equal employment opportunity; elimination of bullying, violence, harassment and discrimination; and prevention of stressful job monitoring practices. In general, policies that are worker centered, participatory in design, and highly flexible advance worker well-being.

The OSH Act places responsibility for worker safety and health directly on the employer. However, employment patterns that rely on jobs that are not permanent and lack a traditional employer–employee relationship (e.g., contracting, subcontracting, and multiemployer worksites and other nonstandard or alternative work arrangements) can make it more challenging to protect workers and advance their well-being (Howard, 2017; Weil, 2014). Increases in what is sometimes referred to as precarious or contingent employment has become a TWH-related issue because it affects worker safety, health, and well-being (Cummings & Kreiss, 2008; Howard, 2017). Data on the size of the workforce employed in these nonstandard work arrangements vary depending on the definition applied; estimates of the size of this workforce range from 8% to 18% of the total workforce (Howard, 2017). According to Katz and Krueger (2016), from 2005 to 2015, alternative work arrangements have accounted for all the net employment growth in the United States, making clear responsibility for the safety and health of these workers imperative in the years ahead.

Leaders at all organizational levels set the tone for TWH through their shared commitment to safety, health, and well-being. Supportive leaders provide responsible decision making and worker recognition and respect. More recently, the issues of worker engagement and meaningful work are of increasing interest. Engagement has been described as “the bringing of one’s self into something outside of the self” (Kahn & Fellows, 2013, p. 106). Engaged workers are the creative force behind the best of what happens in an organization. They support the innovation, growth, and revenue that drive their companies and, hence, overall organizational success. Yet, according to an annual Gallup poll, the percentage of engaged workers was only 32% in 2015, remaining relatively flat since 2011 (Adkins, 2016). Conversely, 68% of workers were either not engaged or actively disengaged (Adkins, 2016). These workers may be present but they characteristically do the minimum to get by or, worse, they are hostile and disruptive. Actively disengaged workers are sicker and miss more days of work (Adkins, 2016). Finding meaning and purpose through work creates opportunities for workers to actively engage in their work.

Meaningful Work

Safe and healthful work provides a platform from which work can become a source of meaning, recognition, and astonishment (Terkel, 1974) to advance individual well-being. Although what is meant by meaningful work has gained little consensus, both subjective and objective components have been considered. For example, believing that one’s work is significant or that it serves an important purpose, perhaps transcending the self, is a subjective experience of meaningful work (Bailey & Madden, 2016; Berg, Dutton, & Wrzesniewski, 2013; Lent, 2013; Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012). Alternatively, focusing on job content or job design to provide meaning in work is an objective approach. For example, jobs that provide autonomy to make a difference, opportunities for personal growth, and the flexibility to align with personal needs and characteristics have objective components that contribute to meaningful work (Bailey & Madden, 2016; Berg et al., 2013).

According to Morin (2004), meaningful work has six characteristics: social purpose, moral correctness, achievement-related pleasure, autonomy, recognition, and positive relationships. Job crafting, as described by Berg and colleagues (2013), provides a process for workers to redefine, reimagine, and recreate their jobs in ways that are personally meaningful. By innovating their work through crafting tasks, relationships, and perceptions, workers have opportunities to incorporate characteristics of meaningful work and create work that is personally meaningful (Berg et al., 2013). In addition to infusing work with meaning, job crafting contributes to job satisfaction, retention of the best employees, and work engagement (Berg et al., 2013). A focus on objective job components can lead to meaningful work that is consistent with higher priority approaches in the hierarchy of controls applied to TWH.

Total Worker Health Hierarchy of Controls

It is tempting to approach worker well-being from the perspective of changing individual behavior or perceptions. However, when promoting health, research demonstrates that “[i]t is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural and physical environment conspire against such change” (Smedley & Syme, 2000, p. 4). Changes to the social, cultural, and physical environment may take longer to accomplish, but in the end, these changes are the most efficient, ultimately less expensive, and more sustainable than attempts to change human behavior.

The OSH professions know that behavior change alone is inadequate. In fact, workplaces have a long history of not relying on individual behavior to assure worker safety and health. The traditional hierarchy of controls (NIOSH, 2016a), fundamental to the education of occupational health nurses, provides an approach to protecting workers from harm. The most effective control is hazard elimination by physically removing the hazard from the work environment. The least effective way to protect workers is through mandating use of personal protective equipment, which relies on worker behavior for effective implementation. In between these two controls, in descending order of effectiveness, are substitution of a less or nonhazardous process, engineering controls to isolate workers from the hazard, and administrative controls that change the way work is done. In general, relying on worker behavior while hazards in the work environment remain uncontrolled is an unacceptable approach to worker safety and health and inconsistent with TWH principles.

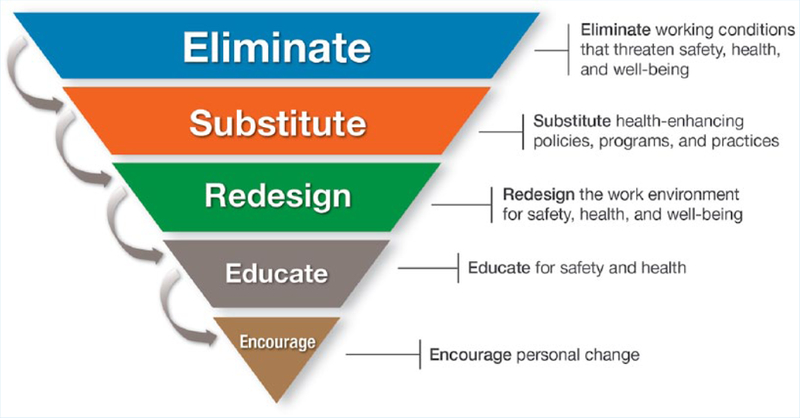

To link traditional OSH approaches and TWH, a hierarchy of controls consistent with TWH has been created (Lee et al., 2016) to augment the traditional hierarchy and provide a conceptual model for prioritizing efforts to advance worker well-being (Figure 2). As in the traditional hierarchy, the controls and strategies are presented in descending order of anticipated effectiveness and protectiveness, as suggested by cascading arrows. Application of this hierarchy of controls begins with elimination of workplace conditions that cause or contribute to worker illness or injury, or otherwise negatively affect well-being. This tier includes factors related to supervision throughout the management chain. The second tier of the hierarchy focuses on replacement of unsafe, unhealthy working conditions or practices with safer, health-enhancing policies, programs, and management practices that improve the culture of safety and health in the workplace. The next level addresses redesign of the work environment, where needed, to promote safety, health, and well-being, for example, the removal of impediments to well-being, enhancement of employer-sponsored benefits, and provision of flexible work schedules. Fourth in the hierarchy is offering safety and health education and resources to enhance individual knowledge for all workers. The last control in the hierarchy is encouragement of personal change to improve health, safety, and well-being by providing workers assistance with individual risks and challenges, including support for making healthier choices.

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of controls applied to Total Worker Health.

Advancing Well-Being

Total Worker Health advances well-being by creating a foundation of safety through which work can contribute to higher levels of well-being. Using Maslow’s (1943, 1969) modified hierarchy of human needs as a reference, work that meets basic physiological, safety, belonging, and esteem needs is good work. But, work that provides opportunities for self-actualization and self-transcendence contributes to the fulfillment of human potential, is great work, and ceases to feel like work. When workers engage in great work, they are fully present, employers benefit from highly productive workplaces, and communities thrive.

Conclusion

Total Worker Health is an approach to worker safety, health, and well-being that comprehensively focuses on the needs, challenges, and opportunities faced by workers as they navigate work in the 21st century. It is perhaps the most challenging approach that occupational health nurses can pursue. A 1976 publication of the history of the American Association of Industrial Nurses (AAIN), included the following assessment:

It has been said that occupational health nursing is the easiest job in the nursing profession to do badly and one of the hardest and most satisfying to do well. To meet the difficult demands of the future, the occupational health nurse will have to be exceptionally well prepared. Besides keeping up with the new techniques of nursing, the nurse in industry will have to become familiar with such new occupational health concepts as the effects of the environment and human emotions on industrial health and safety, and the rapid-fire changes in industrial technology and the pressures they exert on employees (p. 9).

These words are as true today as when they were first written. Fortunately, occupational health nurses of today have a multitude of resources to be perfectly prepared and positioned to rise to this challenge. Total Worker Health is one such resource.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contributions of the Total Worker Health (TWH) Core Team Members in the development of the TWH Program. She is also grateful for the review and comments provided by Dr. L. Casey Chosewood on an earlier draft manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biography

Anita L. Schill is the Senior Science Advisor to the Director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). She is also a Co-Manager for the NIOSH Total Worker Health® Program. She is based in Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adkins A (2016, January 13). Employee engagement in U.S. stagnant in 2015 [Electronic mailing list article] Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/188144/employee-engagement-stagnant-2015.aspx?version-print

- American Association of Industrial Nurses. (1976). The nurse in industry New York, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw A, Pana-Cryan R, & Rosa R (2012). Paid sick leave and nonfatal occupational injuries. American Journal of Public Health, 102, e59–e64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C, & Madden A (2016, June). What makes work meaningful—Or meaningless. MIT Sloan Management Review, pp. 52–61.

- Berg JM, Dutton JE, & Wrzesniewski A (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In Dik BJ, Byrne ZS & Steger MF (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81–104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14183-005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Chronic disease overview Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016b). Depression Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics/mental-illness/depression.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016c). Workers’ Memorial Day—April 28, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 389. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6515a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, & Kreiss K (2008). Contingent workers and contingent health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299, 448–450. doi: 10.1001/jama.229.4.448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J (2017). Nonstandard work arrangements and worker safety and health. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 60, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel PA, Loeppke RR, Baase CM, Burton WN, Hartenbaum NP, Hudson TW, … Larson PW (2011). Workplace health protection and promotion a new pathway for a healthier—and safer— Workforce. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53, 695–702. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822005d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn WA, & Fellows S (2013). Employee engagement and meaningful work. In Dik BJ, Byrne ZS & Steger MF (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 105–126). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14183-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, & Krueger AB (2016). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015 (DataSpace digital repository) Retrieved from http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp01zs25xb933

- Laloux F (2014). Reinventing organizations Brussels, Belgium: Nelson Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MP, Hudson H, Richards R, Chang CC, Chosewood LC, Schill AL, on behalf of the NIOSH Office for Total Worker Health. (2016). Fundamentals of total worker health approaches: Essential elements for advancing worker safety, health, and well-being (Publication No. 2017 112) Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW (2013). Promoting meaning and purpose at work. In Dik BJ, Byrne ZS & Steger MF (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 151–170). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi; 10.1037/14183-008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH (1969). The farther reaches of human nature. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morin EM (2004, August). The meaning of work in modern times. Paper presented at the 10th World Congress on Human Resources Management, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2016a). Hierarchy of controls Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2016b). Total Worker Health® frequently asked questions Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/faq.html

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2016c). What is Total Worker Health®? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/

- Occupational Safety and Health Act. Title 29 United States Code Sections 651–678. 1970.

- Smedley BD, & Syme SL (Eds.). (2000). Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research Washington, DC: National Academy Press. doi: 10.17226/9939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Dik BJ, & Duffy RD (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 20, 322–337. doi: 10.1177/1069072711436160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terkel S (1974). Working New York, NY: Ballantine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Weil D (2014). The fissured workplace Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]